Abstract

Arousal from sleep is a critical defense mechanism when infants are exposed to hypoxia, and an arousal deficit has been postulated as contributing to the etiology of the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The brainstems of SIDS infants are deficient in serotonin (5-HT) and tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) and have decreased binding to 5-HT receptors. This study explores a possible connection between medullary 5-HT neuronal activity and arousal from sleep in response to hypoxia. Medullary raphe 5-HT neurons were eliminated from neonatal rat pups with intracisterna magna (CM) injections of 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (DHT) at P2-P3. Each pup was then exposed to four episodes of hypoxia during sleep at three developmental ages (P5, P15, and P25) to produce an arousal response. Arousal, heart rate, and respiratory rate responses of DHT-injected pups were compared with pups that received CM artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) and those that received DHT but did not have a significant reduction in medullary 5-HT neurons. During each hypoxia exposure, the time to arousal from the onset of hypoxia (latency) was measured together with continuous measurements of heart and respiratory rates, oxyhemoglobin saturation, and chamber oxygen concentration. DHT-injected pups with significant losses of medullary 5-HT neurons exhibited significantly longer arousal latencies and decreased respiratory rate responses to hypoxia compared with controls. These results support the hypothesis that in newborn and young rat pups, 5-HT neurons located in the medullary raphe contribute to the arousal response to hypoxia. Thus alterations medullary 5-HT mechanisms might contribute to an arousal deficit and contribute to death in SIDS infants.

Keywords: arousal, serotonin, medulla, response to hypoxia, rodent development

in infants, arousal from sleep is an important protective response to hypoxia, whether caused by apnea, disrupted breathing, or asphyxia. Arousal leads to actions such as lifting and turning the head that enable an infant to overcome a threatening situation. An arousal deficit has been postulated to contribute to the pathogenesis of the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (25, 26, 29, 36), and arousal responses are reported to be diminished in infants who subsequently die of SIDS (51). In addition, recurrent hypoxic episodes could result in a progressive lengthening of the time to arousal (latency), a phenomenon that has been termed arousal habituation (17, 23, 59).

Because the brainstems of many SIDS infants are deficient in serotonin (5-HT) and tryptophan hydroxylase II (TPH2) (22), and have reduced binding to 5-HT1A receptors, important for regulating the firing rate of 5-HT neurons and the levels of 5-HT (33, 45), we were interested in the possible role of medullary serotonergic neurons in the arousal response to hypoxia. Although it is well known that mesopontine 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) are important in sleep, particularly in models of REM or active sleep (27, 41), less is known about the role of medullary raphe nuclei, including raphe magnus (RM), raphe obscurus (RO), and raphe pallidus (RP) 5-HT neurons, in sleep, and there is no information about their role in the process of arousal in response to hypoxia.

It is thought that medullary 5-HT neurons are involved in setting autonomic and somato-motor tone at a level commensurate with an animal's activity level that changes, for example, with behavioral (arousal) state or in the face of a threat (30). The firing rate of both medullary and mesopontine 5-HT neurons is dependent on state, being highest in wake and lowest in REM sleep (31, 50). In rats and piglets, dialysis of 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT), a selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist that decreases the activity of exposed 5-HT neurons, into the medullary raphe resulted in an increase in wakefulness and in some cases a decrease in active sleep (9, 16, 54). These results are in contrast to those obtained with dialysis of 8-OH-DPAT into the DRN which are reported to decrease tissue 5-HT and the amount of wakefulness and increase the amount of REM sleep (48). These contrasting results suggest possible regional differences in the roles of 5-HT neurons in sleep.

We propose that 5-HT neurons located in the medullary raphe, encompassing the RO, RM, and RP, and possibly the paragigantocellularis lateralis, play an important role in the arousal response to respiratory stimuli, including hypoxia. The mechanisms for arousal or arousal habituation to respiratory stimuli have not been completely defined. However, in young infants, dysfunction in the autonomic and/or somatic components of arousal would likely lead to an impaired ability to adequately defend against periods of hypoxia experienced during sleep. We have previously shown that medullary raphe neurons contribute to the process of arousal in response to hypoxia and that GABAergic mechanisms are involved (18). In the current study, we explore the influence of medullary raphe 5-HT neurons on arousal and arousal habituation in response to hypoxia in the developing rodent at three ages: P5, P15, and P25. The selection of ages was based on studies of the rate of growth of the brain (21), the maturation of various brain stem neurotransmitter systems (3, 40, 60), sleep and arousal (7, 19, 23, 32, 42, 53), the autonomic control of HR (28), and thermoregulation (1, 11, 35, 44). These comparisons suggest that the period from P1 to P8–P10 is roughly equivalent to the third trimester of pregnancy (or premature infants) in the human, the period from P10 to P20 is roughly equivalent to infancy, and the period from P20 to P30 is roughly comparable to adolescence. We hypothesize that destroying the majority of 5-HT neurons in the medullary raphe will lengthen the time to arousal and potentiate arousal habituation in response to repeated acute episodes of hypoxia and that any effects will be affected by age.

METHODS

Subjects.

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Dartmouth College and conformed to ethical standards. Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories) were housed under standard conditions in the Dartmouth College animal facility. Lighting was on between 7 AM and 7 PM, and the room temperature was kept at 72 ± 2°F. Three litters bred in-house were culled to 12 pups within 2 days of birth. Approximately equal numbers of male or female pups from each litter were given an intraperitoneal injection of desipramine and then received intracisternal injections of either artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or the neurotoxin, 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (DHT): litter 1 (no. aCSF/no. DHT: 6/6), liter 2 (6/6), and litter 3 (5/7). Eight animals died before arousal testing was completed and included four pups injected with aCSF and four pups injected with DHT. Two pups died from litter 1, two from litter 2, and four from litter 3. Thus 13 aCSF and 15 DHT-injected pups completed the study. Postnatal day zero (P0) was considered the day of birth. All experiments were performed between 9 AM and 5 PM.

DHT and aCSF administration.

To avoid noradrenergic cell loss from DHT, all of the pups received an intraperitoneal injection of desipramine (ip 20 mg/kg, 2 mg/ml in saline, Sigma) 1 h before DHT or aCSF administration (5, 6). Pups were placed in a glass cylinder in an ice bath for 15 min to reach a hypothermic anesthetic plane as described by Danneman (15). An incision at the rear of the scalp was made, and muscle and skin retracted to expose the base of the skull. A Hamilton syringe (10 or 25 μl, 30–33 ga needle) was held in a stereotaxic manipulator, and the needle was passed through the atlanto-occipital membrane into the cisterna magna (CM). Artificial cerebrospinal fluid [in mM: Na+ 150, K+ 3.0, Ca2+ 1.4, Mg2+ 0.8, P3+ 1.0, Cl− 155, pH 7.4; ascorbic acid 0.1%, or DHT (50 μg in 2 μl of aCSF, Fluka)] was injected into the CM at P2 or P3. Injections were made over 5 min, and the syringe needle was removed after another 5 min. After suturing, pups were placed in a warm environment to recover before returning to the litter.

Arousal test.

The ability to arouse to repeated episodes of hypoxia was determined in each pup at postnatal day 5 ± 1, 15 ± 2, and 25 ± 2 (P5, P15, and P25). We have previously shown that hypoxia is an effective arousal stimulus in rat pups at these ages, and descriptions of our techniques have been described previously (17, 18). Briefly, pups were fitted with a vest that held surface ECG electrodes and a piezoelectric film motion sensor to record respiratory frequency (fR) and body movement. A 36-ga flexible thermocouple (Omega Engineering) was inserted into the lower colon to record body temperature (TB). In some pups, blood oxyhemoglobin saturation (HbO2Sat) and a second measure of heart rate (fH) were derived from pulse oximetry by using either a neck or tail sensor (Starr Life Sciences).

Pups were placed prone or on their side in a cylindrical, double-walled acrylic chamber warmed by circulating water to thermoneutral temperature (wall temperature: P5, 34°C; P15, 33°C; P25, 32°C). The chamber volume was 180 ml for P5 and P15 pups and 500 ml for P25 animals. Breathing gases were supplied from high-pressure sources equipped with automated solenoid valves to allow rapid switching between room air and 10% oxygen (balance nitrogen). Gas was heated to 30°C, directed to a 5-cc vented tube, and then drawn through the chamber under mass flow control at a constant 250 ml/min (P5 and P15) or 500 ml/min (P25). Continuous measurements of chamber pressure (Validyne) assured that gas source switching produced only negligible pressure change and provided a second measure of fR. Oxygen (Sable Systems) and carbon dioxide (CWE, Inc.) analyzers sampled dried gas leaving the chamber. All signals were recorded with a commercially available data acquisition system (AD Instruments) for later analysis. We have previously shown that by using this experimental protocol, the rates of decrease in chamber oxygen concentration (ChO2) during hypoxia exposures were similar for all ages (18).

Pups slept readily in the warmed chamber, and were judged to be awake, in quiet sleep (QS), or active sleep (AS) by observation. We and others have shown that the determination of sleep and wakefulness can be accomplished without electroencephalographic measurement in young rats and mice by using behavioral criteria (2, 17–19, 23, 52). Quiet sleep (quiet immobility) was characterized by lack of movement, closed eyes, and regular fH and fR. Active sleep was characterized by myoclonic twitching of face or limbs on a background of immobility. The pup was judged to be awake if the criteria for QS or AS were not met. Usually, there was considerable movement during wakefulness.

After an acclimation period of ∼10 min in the chamber, pups were exposed to four 3-min trials of hypoxia separated by 6 min of normoxia. All trials were initiated in QS as defined above. During each trial ChO2 decreased to 10% over 50 s and then remained constant for an additional 130 s. There was some variation in the recovery time to allow the pup to achieve QS before the onset of the next trial. Thus the total cycle time (hypoxia + recovery) for each trial was ∼9 min and the total time for each experiment was ∼40 min.

The time to arousal from sleep after the start of a hypoxia trial (arousal latency) was recorded by the observer. Arousal was determined by observing forelimb and neck extension, and head rearing, a coordinated motion that likely reflects cortical activation (17, 18, 42). This stereotypical response is characteristic of a “state change” from sleep to wakefulness and should be distinguished from brief spontaneous “mini arousals” that occur frequently during both QS and AS. These awakenings were accompanied by large movements detected both visually and by the piezoelectric motion detector. After arousal, during the remainder of the hypoxic period, pups were active for variable periods of time and frequently reentered sleep. Pups were returned to the litter after each experiment. The order of experiments with aCSF or DHT-treated pups was determined randomly, and the experimenter was blind to the treatment (aCSF or DHT) of the animals tested.

After all experiments were completed for a litter (at P25), brain tissue was prepared for immunohistochemical analysis. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg, respectively), and tissue fixed by transcardial perfusion with 0.1 M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then dissected, postfixed 2–3 days at 4°C, and stored in PBS at 4°C.

Histology.

Brains were equilibrated in 25% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS, frozen, and sectioned (40 μm). Every fourth section was processed free-floating for immunohistochemical detection of tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) by using a sheep antiserum (Millipore). The primary antiserum was diluted in 0.1 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.05% BSA, and 0.1% sodium azide. Sections were incubated with the primary antisera 2–3 days at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, sections were incubated with CY3 conjugated donkey antisheep secondary antisera (Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted 1:200 in PBST-BSA. After rinsing, sections containing the pons and medulla were mounted on glass slides and cover slipped with a glycerol based mounting medium. Sections were photographed with conventional epifluorescence illumination.

Two phases of analysis were conducted to evaluate the effect of the DHT infusion on 5-HT neurons. In the first phase, tissue sections from each rat were qualitatively evaluated to characterize the extent of the lesion. Subsequently, cases were coded and a quantitative analysis was completed blind to the treatment group. For this, three sections were sampled from each rat centered on the RM (bregma −10.30 mm) (see Fig. 1). Every TPH-immunolabeled cell visible within the triangular area encompassing RM was counted, and the average number of cells per section was generated for each individual rat pup.

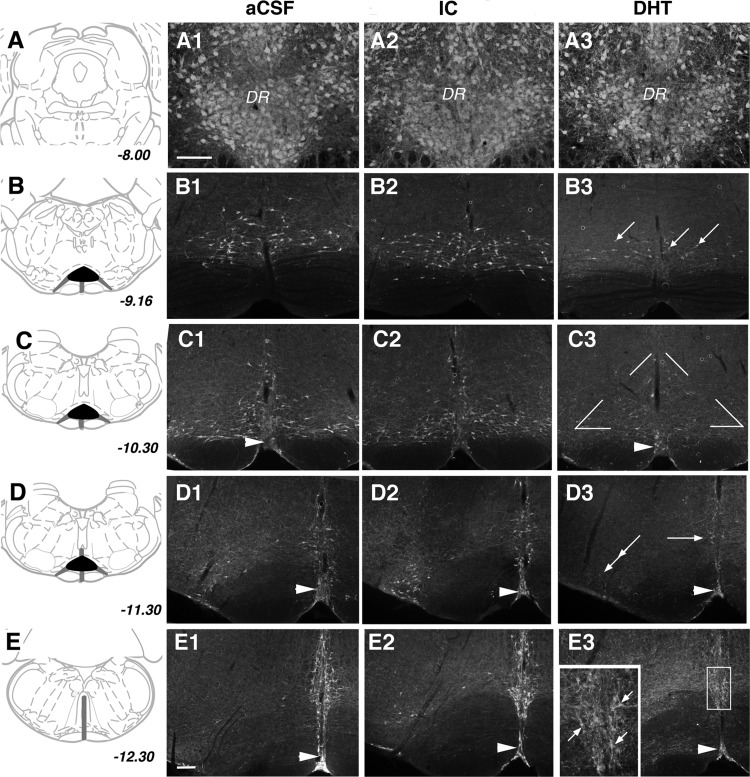

Fig. 1.

A–E: 5-HT neurons at five different levels through the hindbrain and medulla illustrated schematically with corresponding coordinates relative to Bregma. Characteristic distribution of 5-HT neurons in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) (A1–E1), injection control (IC) (A2–E2), and 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (DHT) (A3–E3) rat pups. Areas that appeared profoundly or partially impacted by the lesion are represented by the black and dark gray zones, respectively (A1–A3). In all groups, densely packed neurons immunolabeled for tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) were visible in the dorsal and ventral parts of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) (B1–B3). At the rostral pole of the raphe magnus (RM) in aCSF and IC groups, TPH-immunolabeled cells were visible in a dispersed pattern (B3). In DHT pups many fewer cells were visible (arrows) (C1–C3). Compared with aCSF and IC pups (C1 and C2), DHT pups (C3) show a profound loss of neurons within RM (triangular area indicated in C3 dorsal to the pyramids). In contrast, 5-HT neurons in raphe pallidus (single arrowhead) are visible both in aCSF and DHT cases (D1–D3). In comparison to aCSF (D1) and IC (D2), in DHT pups (D3) there was a loss of cells in RM (single arrow) and as well laterally in the paragigantocellularis lateralis (double arrows), although TPH immunoreactivity persisted to some extent in raphe pallidus (single arrowhead) (E1–E3). At the level of raphe obscurus, there were fewer 5-HT neurons and/or neurons with abnormal morphology in DHT pups; boxed region shown at higher magnification in inset. A1–A3 same scale and B–E same scale; bars in A1 and E1 = 250 microns.

Data analysis.

The control group (aCSF group, n = 13) consisted of the 13 surviving pups of the 17 injected with aCSF. The treatment group initially consisted of the 15 survivors of the 19 pups injected with DHT. However, some of the DHT-injected pups did not have cell counts statistically different from aCSF injected pups. We elected, therefore, to base our analysis on the histological findings rather than whether or not DHT was administered. Thus the DHT-injected pups were further divided into two groups based on the histologic confirmation of a lesion: those with confirmed loss of medullary raphe 5-HT neurons (DHT group, n = 9) and those with medullary raphe 5-HT cell counts equivalent to controls, designated the injection control (IC) group (n = 6). To determine whether the experimental procedure, including hypothermia, surgery and injections, and the administration of intraperitoneal desipramine, affected arousal or arousal habituation, the two control groups (aCSF and IC) were compared with an additional historical control group (HC) (n = 38) that were tested similarly at P5, P15, and P25 and received normal handling, no surgery or injections, and no systemic administration of desipramine.

For each hypoxia trial, the time to arousal (latency) was determined as the time from gas switch to arousal. Baseline values (mean of 10 s of data prior to hypoxia) and values at the time of arousal were determined for HbO2Sat, TB, ChO2, fH, and fR. In addition, baseline values for oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇co2) were determined. V̇o2 was calculated as V̇o2 = {flow[(FiO2-FeO2)−FiO2(FeCO2-FiCO2)]/(1-FiO2)}/wt. Similarly, V̇co2 was calculated as V̇co2 = {flow[(FeCO2-FiCO2)+FiCO2(FiO2-FeO2)]/(1+FiCO2)}/wt (37). A mixed model was used to compare variables (SPSS v22). Our initial analyses showed no main effect of sex and no interaction of sex with age, group (aCSF, DHT, IC), or hypoxia trial (1–4). Thus sex was not included in the final analysis. Litter number nested within “group” was included as a random factor to account for possible litter effects, as has been suggested by others (24, 56, 61). In addition, a Cox regression model was used to evaluate arousal latency. Pairwise comparisons of main effects and interactions were performed with corrections for multiple comparisons (Sidak).

RESULTS

Neuroanatomy.

An examination was done, blind to the treatment group, of the immunohistochemical distribution of TPH, a marker of 5-HT neurons, and revealed that many but not all of DHT-injected pups had a profound loss of 5-HT neurons within the medulla, with the most obvious loss within the RM (Fig. 1). In addition, there was also a reduction in TPH-immunolabeled neurons and/or neurons identified with abnormal morphology within the paragigantocellularis lateralis (PGCL) and the RO. By comparison, 5-HT neurons in the mesopontine dorsal and median raphe nuclei and the raphe pallidus appeared unaffected (Fig. 1). We used cell loss in the RM as a quantitative estimate of loss in other caudal raphe nuclei based on previous studies from our laboratories showing profound losses of 5-HT neurons from the RM after CM administration of 5,7-DHT and similar losses in other caudal raphe nuclei, with sparing of cell loss in the raphe pallidus (12).

Our analysis revealed a profound loss of 5-HT neurons in many DHT-injected pups. However, in some DHT-injected pups we did not observe the expected cell loss in the RM. DHT-treated pups in which the number of 5-HT neurons in the RM was within one standard deviation from the mean of that in aCSF-treated pups were grouped separately as an IC group. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the degree of 5-HT cell loss in the DHT and IC group compared with the aCSF controls.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative counts of TPH immunoreactive (TPH+) neurons in the RM. A: scatter graph showing the total cell counts in the aCSF (○), DHT (○) and IC (△) pup brains. B: bar graph showing the average cell counts for the three groups. The mean number of TPH+ cells in the DHT group was significantly less than in the aCSF or lesion control groups (*P < 0.001). Values are expressed as means ± SD.

Baseline data.

Baseline values, obtained before the first trial of hypoxia, for the aCSF, IC, and DHT groups at the three ages are shown in Table 1. At P15 and P25, pups in the DHT group weighed less than pups in the two control groups (P < 0.001). Overall, baseline TB was higher at P25 compared with P5 (P = 0.005) and P15 (P < 0.001) pups, but differences reached significance only in the aCSF (P = 0.002 and P = 0.001 for P25 vs. P5 and P25 vs. P15, respectively) and DHT (P = 0.006, P25 vs. P15) groups. Overall, baseline TB in the DHT group was not different from baseline TB in the two control groups. As expected, baseline fH increased with age (P < 0.001), and there was a significant interaction between age and treatment (P < 0.004). Baseline fH increased with age in all treatment groups (P < 0.007) but increased the least in the DHT group. Interestingly, at P25, baseline fH in the IC group was substantially higher than in the aCSF (P = 0.010) or the DHT (P = 0.002) group. Across all treatment groups baseline fR was lower at P5 compared with P15 and P25 (P < 0.004). Examination of the interactions, however, revealed that the age effect was only apparent in the IC group (P = 0.005 and P = 0.001 for P5 vs. P15 and P5 vs. P25, respectively). There was no effect of treatment on mean baseline fR at any age. Baseline HbO2Sat was within the range of normal at all ages but was slightly lower at P25 compared with P15 and P5 (P < 0.001). Mean baseline V̇o2 averaged across all treatment groups was lower in P5 pups compared with P25 pups (P = 0.008). At P25, the mean V̇o2 in the DHT group was significantly lower than in both the aCSF (P = 0.045) and the IC (P = 0.009) group.

Table 1.

Baseline variables

| P5 |

P15 |

P25 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aCSF | Injection Control | DHT | aCSF | Injection Control | DHT | aCSF | Injection Control | DHT | |

| N, m:f | 13 (5:8) | 6 (3:3) | 9 (4:5) | 13 (5:8) | 6 (3:3) | 9 (4:5) | 13 (5:8) | 6 (3:3) | 9 (4:5) |

| Age, days | 5.9 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.3) | 6.0 (0.3) | 15.0 (0.3) | 15.0 (0.5) | 15.4 (0.4) | 23.6 (0.3) | 25.3 (0.5) | 24.1 (0.4) |

| Weight, g | 12.5 (0.5) | 9.9 (0.4) | 9.8 (0.8) | 33.5 (0.6 | 34.9 (1.4) | 24.2a (1.6) | 63.7 (1.7) | 70.9 (3.7) | 49.5a (3.2) |

| TB, °C | 36.06 (0.19) | 35.80 (0.26) | 36.00 (0.22) | 35.88 (0.19) | 35.38 (0.26) | 35.67b (0.22) | 36.91+ (0.19) | 35.91 (0.26) | 36.45c (0.22) |

| fH, bpm | 398.6 (5.5) | 417.6 (7.5) | 404.7 (9.9) | 446.5 (8.0) | 467.4 (13.9) | 430.0 (11.8) | 469.5 (9.7) | 538.7d (15.8) | 451.2 (8.4) |

| fR, bpm | 118.1 (10.9) | 87.5e (14.0) | 118.2 (11.5) | 122.8 (10.9) | 124.5 (14.0) | 131.5 (11.5) | 134.0 (10.9) | 131.7 (14.0) | 116.8 (11.5) |

| HbO2SAT, % | 98.4 (0.6) | 99.1 (0.2) | 98.5 (0.7) | 98.9 (0.5) | 99.6 (0.1) | 98.9 (0.5) | 96.0 (0.8) | 96.8 (0.7) | 97.4f (0.7) |

| V̇o2, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 28.17g (2.13) | 28.74 (3.13) | 26.67 (2.90) | 31.66 (2.13) | 31.83 (3.13) | 30.87 (2.55) | 34.79 (2.21 | 38.83 (3.13) | 29.88h (2.55) |

Values are means ± SE; values obtained before hypoxia trial 1. Significance at P < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons (Sidak).

aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid; DHT, 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine; TB, body temperature; fH, heart rate; fR, respiratory frequency; HbO2SAT, blood oxyhemoglobin saturation.

DHT < control groups at P15 and P25;

P25 > P15 and P5 in aCSF group;

P25 > P15 in DHT group;

lesion control group higher than aCSF or DHT groups only at P25;

P5 < P15 and P25 in injection control group;

P25 < P5 and P15 across all groups;

P5 < P15 and P25 across all groups.

DHT < aCSF and injection control groups at P25.

Arousal latency.

Arousal latency was determined as the time from the onset of hypoxia to the observed arousal from sleep during four repeated hypoxia exposures. To determine whether ice anesthesia or the injection procedure affected our results, we compared arousal latencies in response to hypoxia in the two control groups with latencies in a third historical control group that received normal handling. Each pup was tested at P5, P15, and P25. There were the expected main effects of age (P < 0.001) and trial (P < 0.001) but no differences in arousal latency between control groups at any age. Figure 3 shows arousal latencies for the three control groups during the four trials of hypoxia trials in P5, P15, and P25 pups.

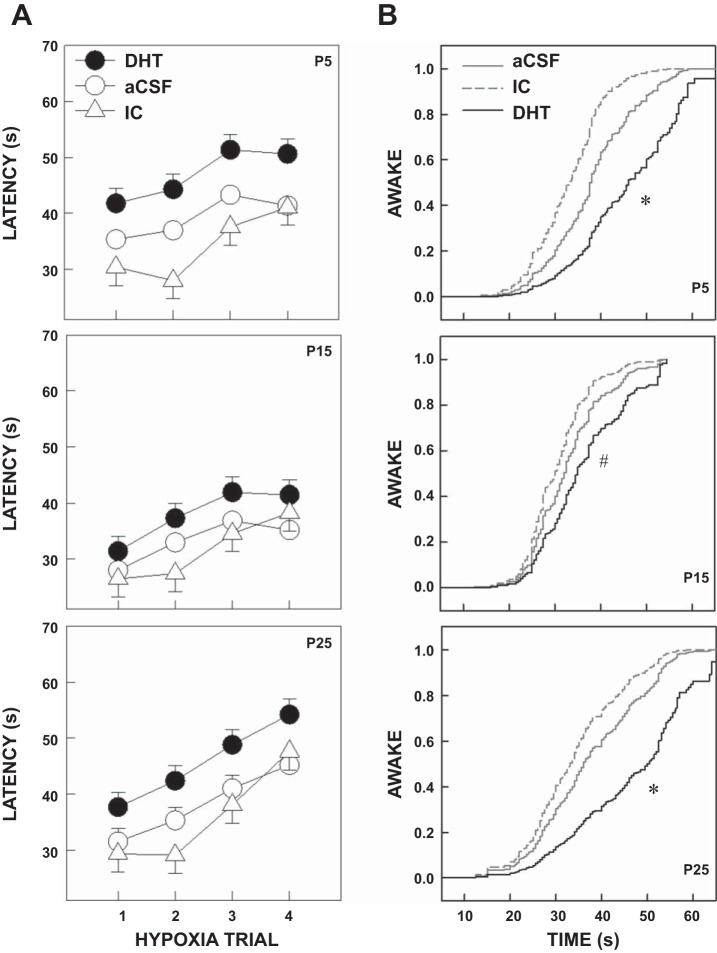

Fig. 3.

Arousal latencies for the aCSF, IC, and historical control (HC) groups. A: mean arousal latencies, averaged over all trials for P5, P15, and P25 pups. B: arousal latencies for the three ages over four hypoxia trials for the three control groups. Pups in the HC group were not exposed to surgery, injections, or desipramine. There were no significant differences overall or at any age. Data are shown as means ± SE.

When the aCSF, IC, and DHT groups were compared, there were significant main effects of treatment (P = 0.008), age (P < 0.001), and hypoxia trial (P < 0.001). Arousal latencies (averaged across all trials and ages) were longer for DHT compared with IC (P = 0.008) and aCSF (P = 0.034) pups. Overall, the shortest mean latencies were found in P15 pups compared with P5 (P < 0.001) and P25 (P < 0.001) pups. Latency increased over the four hypoxia trials (habituation) at all ages and in all treatment groups (P < 0.001). However, the degree of habituation, measured as the slope across trials, was not different among treatment groups. Figure 4 shows the main effect of treatment (first set of bars labeled “Main”) and the effect of treatment by age (three sets of bars labeled by age). Note that arousal latency was significantly longer in the DHT pups compared with the two control groups at P5 and P25. Figure 5A shows the effect of treatment on arousal latency across the four hypoxia trials at P5, P15, and P25. Cox regression analysis confirmed that the probability of arousal during hypoxia was significantly lower in the DHT group compared with the two control groups (P < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 5B, consistent with our mixed model analysis, this was particularly evident at P5 and P25, but in this analysis the comparisons were also different at P15.

Fig. 4.

Mean arousal latencies, averaged across hypoxia trials by age. Latencies of pups injected with DHT (black bars) were compared with those in pups injected with aCSF (white bars with no hatching) and those injected with DHT but without a significant reduction of medullary 5-HT neurons (IC group) (white bar with course hatching). There was an overall (across all ages and hypoxia trials) lengthening of arousal latency associated with a reduction in the number of medullary 5-HT neurons. As shown in the first group of bars (MAIN), overall, arousal latencies were longer in the DHT group compared with the IC (*P = 0.008) and the aCSF Control group (*P = 0.034). The effect of 5-HT neuronal loss was most pronounced at P5 and P25. At P5 arousal latencies were longer in the DHT group compared with the IC group (#P < 0.001) and the aCSF group (#P = 0.011). At P25 arousal latencies were longer in the DHT group compared with the IC group ($P = 0.021) and the aCSF control group ($P = 0.035). At P15, arousal latencies were also longer in the DHT group compared with the aCSF and IC group, but the differences did not reach significance after correcting for multiple comparisons. Values are indicated as the mean ± SE.

Fig. 5.

A: arousal latencies across four repeated hypoxia trials at P5, P15, and P25. Pups were exposed to four episodes of hypoxia (10% O2) begun in quiet sleep and the latency to subsequent behavioral arousal determined. Latencies of pups with loss of 5-HT neurons after DHT administration (●) were compared with those in pups injected with aCSF (○) and those injected with DHT but without a significant reduction of medullary 5-HT neurons (△). Latency increased with successive trials (habituation) in all treatment groups (P < 0.001). The mean arousal latency was greatest in the DHT pups at P5 and P25 (see Fig. 4). Values are expressed as the mean ± SE. B: Cox regression analysis showing the proportion of pups awake at various times after the onset of hypoxia. For any given time, the probability of being awake was lower in the DHT groups compared with the controls at all ages. For example, at P25, 40 s after the onset of hypoxia, 60–75% of the control pups had aroused but only 33% of the DHT-treated pups. Consistent with our mixed model analysis, the effects of DHT were more prominent at P5 (*P < 0.001) and P25 (*P < 0.001) compared with P15 (#P = 0.039).

Chamber oxygen concentration and oxyhemoglobin saturation at the time of arousal.

Arousal occurred before chamber O2 (ChO2) reached its nadir. Therefore, the ChO2, measured at the time of arousal, was inversely proportional to latency (data not shown). Similar to arousal latency, there were significant main effects of treatment (P < 0.001), age (P = 0.019), and hypoxia trial (P < 0.001) on ChO2 at the time of arousal, with a significant interaction between treatment and age (P < 0.001). Overall, the mean ChO2 at arousal, averaged across all ages and hypoxia trials, was lower in the DHT pups than in the aCSF (P = 0.002) or IC (P < 0.001) pups. Mirroring the progressive increases in arousal latency across the four trials of hypoxia, the ChO2 at arousal progressively decreased across trials in all treatment groups.

There was significant variability in the HbO2Sat measurements, as pulse oximetry was not reliable or done in all experiments. Nevertheless, overall, the decreases across trials in HbO2Sat at the time of arousal also mirrored the increases in latency (data not shown) with main effects of treatment (P = 0.016), age (P < 0.001), and trial (P < 0.001), with an interaction between treatment and trial (P = 0.037). Thus mean HbO2Sat at the time of arousal, averaged across all ages and trials, was lower in the DHT pups compared with the IC pups (P = 0.004). By hypoxia trial 4, the HbO2Sat in the DHT pups was lower than in both the IC (P = 0.027) and the aCSF (P = 0.002) pups.

Respiratory frequency.

Prehypoxia fR measured before the onset of each hypoxia trial did not change across trials at any age. There was also no main effect of treatment, but there was a main effect of age (P < 0.001) and an interaction between age and treatment (P = 0.001). Figure 6A illustrates the main effect of age and the interaction between age and treatment for prehypoxia fR. Overall, the mean prehypoxia fR, averaged across all treatments and trials, was lower at P5 compared with P15 (P < 0.001) and P25 (P < 0.001), but the age difference was dependent on treatment group and significant only in the IC (P < 0.001 for P5 vs. both P15 and P25) and DHT (P < 0.001 for P5 vs. both P15 and P25) groups. There were no differences in mean prehypoxia fR, averaged across the four hypoxia trials among treatment groups at any age.

Fig. 6.

A: mean prehypoxia respiratory frequency (fR), averaged across trials and ages (first group of bars, Main), and across trials at P5, P15, and P25 for the DHT, aCSF, and IC treatment groups. The mean fR was lower at P5 compared with P15 and P25 (*P < 0.001) in the IC and DHT groups, and there was no effect of treatment on fR at any age. B: mean slope of fR from the onset of hypoxia to arousal averaged across ages and trials (first group of bars, Main) and at P5, P15, and P25 for the DHT, aCSF, and IC treatment groups. Overall, the slope of fR was lower in the DHT pups compared with the aCSF (*P = 0.002) and IC (P = 0.005) pups. The fR slope was lower in DHT than the aCSF or IC pups at both P5 (#P < 0.001 vs. both aCSF and IC) and P15 ($P < 0.001 vs. both aCSF and IC). The fR slope was also lower in the DHT compared with the aCSF pups at P25, but this did not reach significance (P = 0.053). C: the relationship between the slope of the fR response during hypoxia and arousal latency. Control pups are shown as ○ and DHT pups as ●. Note that there is generally an inverse relationship between slope and arousal latency with no effect of DHT treatment. The regression coefficient for the control pups was −3.339, P < 0.001, and for the DHT pups, −4.597, P = 0.0057. Values in the bar graphs are expressed as the means ± SE.

In all treatment groups, fR increased beginning within seconds of the gas changeover and in most instances reached a maximum after arousal. We calculated the rate of rise (slope) of fR (bpm/s) for each treatment group at each age and for each hypoxia trial. The main effects and interactions are shown in Fig. 6B. Overall, the mean slope of the increase in fR up until the time of arousal, averaged across all ages and trials, was significantly lower in the DHT pups compared with both the aCSF (P = 0.004) and the IC (P = 0.009) pups. There was no main effect of age, but there was a significant interaction of treatment and age (P < 0.001) such that the differences in slope between the DHT and both control pups were evident at P5 (P < 0.001) and P15 (P < 0.001) but not at P25 (P = 0.053). In addition, the mean slope of fR, averaged across all treatments and trials, was greatest in P15 compared with both P5 (P < 0.001) and P25 (P < 0.001) pups. There was no change in the slope of the fR response across trials at any age. Figure 6C shows a regression analysis of arousal latency on fR slope comparing the DHT group with the combined aCSF and IC controls. The controls were combined in this figure because the mean values of fR slopes were almost identical. There was an inverse relationship between the slope of the fR response and arousal latency, but this relationship was not influenced by treatment or age.

The fR continued to increase after arousal and reached a maximum after arousal during the remainder of the 3-min hypoxia period (data not shown). Overall, across all treatment groups, the mean maximum fR was higher in the P15 pups compared with the P25 pups (229 ± 4 bpm vs. 203 ± 5 bpm, P < 0.001). In addition, the DHT group had a lower mean maximum fR across all ages and hypoxia trials compared with the aCSF control group (206 ± 8 bpm vs. 228 ± 4 bpm, P = 0.041). Taken together, these results suggest that DHT treatment impairs both the fR and the arousal response to hypoxia, but does not appear to influence the relationship between rate of increase of fR and arousal latency.

Heart rate.

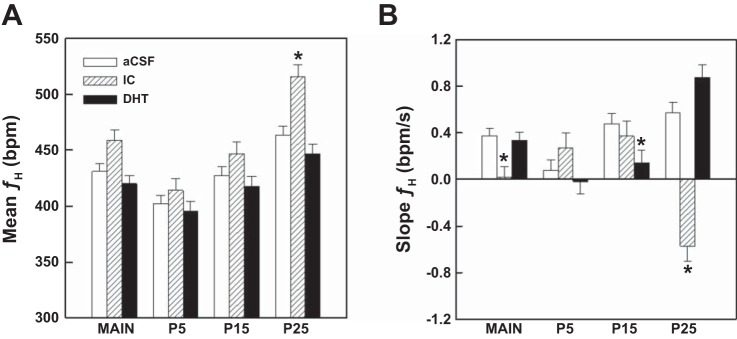

Figure 7A illustrates the mean prehypoxia values for fH across treatments and ages. Overall, prehypoxia fH increased with age (P < 0.001) in all treatment groups. Mean prehypoxia fH was significantly higher in the IC group at P25 compared with both the aCSF (P = 0.003) and DHT (P < 0.001) groups. Over the course of the four hypoxia trials, prehypoxia fH decreased from hypoxia trial 1 to trial 2 and then remained stable across trials 3 and 4 in the P15 (P < 0.001) and P25 (P = 0.003) pups, but there was no change in fH across trials in the P5 pups.

Fig. 7.

A: mean prehypoxia heart rate (fH) averaged across all ages and hypoxia trials and across all trials for P5, P15, and P25. Overall, fH increased with age in all treatment groups. This was especially the case in the IC group where baseline fH was significantly higher than the aCSF (*P = 0.003) and the DHT (*P < 0.001) group at P25. Although the mean fH was higher in the IC group compared with the other two groups at P5 and P15, the differences did not reach significance. Values are expressed as the means ± SE. B: slopes of the changes in fH from the onset of hypoxia to arousal. Overall, similar to fR, the slope of fH increased with age. Averaged across all ages and hypoxia trials, the fH slope was slightly lower in the IC group compared with the aCSF (P = 0.022) and DHT (P = 0.034) groups. This was largely because at P25 the slope of the fH response was negative and significantly different from the slopes in the two control groups (*P < 0.001). In addition, at P15 the fH slope was lower in the DHT pups compared with the aCSF pups (P = 0.028). Values are expressed as the means ± SE.

Similar to the respiratory frequency response to hypoxia, fH increased after the onset of hypoxia and reached a peak after arousal in most cases. The absolute change in fH up until the time of arousal was dependent on age (P = 0.003) and hypoxia trial (P = 0.001) with an interaction between age and treatment (P < 0.001). Overall, the increase in fH was lowest in P5 compared with P15 (P = 0.006) and P25 (P = 0.002) pups. The increase averaged 3.8 ± 2.7 bpm at P5, 12.2 ± 2.7 bpm at P15, and 13.4 ± 2.7 bpm at P25. We also calculated the slope of the fH response up until the time of arousal, and these data are shown in Fig. 7B. The slope, averaged across all treatments and hypoxia trials, was lower at P5 than at P15 (P = 0.007) and P25 (P = 025). However, the age affect varied by treatment. In the aCSF group, the slope was lower at P5 compared with P15 (P = 0.001) and P25 (P < 0.001). In the DHT group, the slope at P5 and P15 were both lower than at P25 (P < 0.001). In contrast, in the IC group the slope was unexpectedly negative at P25 compared with the positive slopes at P5 (P < 0.001) and P15 (P < 0.001). There was a small but significant main effect of treatment (P = 0.049) such that the mean fH slope, averaged across all ages and trials, was lower in the IC pups compared with the aCSF (P = 0.022) and the DHT (P = 0.034) pups. This was largely due to the unexpected negative slope at P25 (−0.57 bpm/s) compared with the positive slopes in both the DHT (0.88 bpm/s, P < 0.001) and the aCSF (0.57 bpm/s, P < 0.001) group. In addition, at P15 the slope of fH was lower in the DHT pups than in the aCSF pups (P = 0.028). Regression analysis failed to show a relationship between the slope of the fH response and arousal latency for any age or treatment.

Metabolic rate and body temperature.

V̇o2, V̇co2, and respiratory quotient (RQ) were calculated prior to the onset of each hypoxia trial. Prehypoxia V̇o2 averaged across all treatment groups and hypoxia trials increased with age (P < 0.001). Across all ages and groups, prehypoxia V̇o2 increased from trial 1 to trial 2 and then remained stable (P = 0.03). At P25 but not at P5 or P15, baseline V̇o2 measured before the first hypoxia trial was lower in the DHT group compared with both the aCSF (P = 0.045) and the IC (P = 0.009) groups (see Table 1), but the difference was no longer evident after trial 2. Across all ages, prehypoxia V̇co2 before the first hypoxia trial was higher than before trials 2–4 (P ≤ 0.001) and averaged across all treatment groups and hypoxia trials was lowest at P15 compared with P5 (P = 0.041) and P25 (P < 0.001). The decreasing V̇co2 with repeated episodes of hypoxia accompanied by the increasing V̇o2 across trials resulted in a decrease in the RQ across trials.

Interestingly, mean prehypoxia TB, averaged across treatments and trials, was lowest in the P15 pups, averaging 0.30 ± 0.12°C lower than in P5 pups (P = 0.032) and 0.34 ± 0.12°C lower than in P25 pups (P = 0.012). Moreover, TB increased across hypoxia trials in P5 pups (0.369 ± 0.058°C/trial) and P15 pups (0.403 ± 0.058°C/trial) but not in P25 pups (0.058 ± 0.059°C/trial). Although there was no main effect of treatment on prehypoxia TB, a difference in the rate of rise across hypoxia trials was seen at P5, where the TB slope across trials was relatively flat for pups in the DHT and IC groups compared with a positive slope in the aCSF pups. Thus by hypoxia trial 4, TB was lower in the DHT and IC groups compared with the aCSF group (P = 0.010 and P = 0.032, respectively). The changes in TB across hypoxia trials for the three treatment groups in the P5 pups are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Prehypoxia body temperature (TB) across the four hypoxia trials at P5 for the three treatment groups. The increase in TB across trials was significantly less in the DHT and IC groups compared with the aCSF control group. By hypoxia trial 4, TB in the aCSF group was significantly higher than in the IC (*P = 0.020) or the DHT (*P = 0.034) group. Values are expressed as the means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of the study was that targeted destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons in neonatal rats lengthened the time to arousal from sleep in response to repeated hypoxia exposure over the course of development. We did not, however, find any effects of 5-HT neuronal destruction on arousal habituation. The effects on arousal latency were most robust at P5 and P25 and marginally present at P15. Previous studies in our laboratories using a similar DHT protocol showed that medullary raphe loss of 5-HT neurons after CM administration at P1–P3 was associated with a 80% reduction in medullary tissue 5-HT level (12). Nevertheless, our study did not resolve whether the effect on arousal resulted directly from a serotonergic deficiency or, alternatively, was caused by abnormal development following early postnatal serotonergic cell loss. Medullary serotonergic innervation of the spinal cord during the neonatal period is important for spontaneous activity that is considered necessary for normal development. It has been shown previously that intraventricular DHT treatment in rat pups results in modest defects in growth (corroborated in the current study), hormone expression, and locomotor activity (8, 34), but the effect of medullary 5-HT neuronal destruction on arousal in response to hypoxia has not been previously reported.

Our previous investigation of medullary GABAergic mechanisms in hypoxic arousal indicated that the medullary raphe plays an important role in arousal during hypoxia, and that GABA neurotransmission is involved. Thus microinjections into the medullary raphe of muscimol, a GABAA receptor agonist, presumably by decreasing the activity of neurons of many phenotypes, prolonged both arousal in response to hypoxia and spontaneous awakenings that occurred during normal sleep cycling, indicating that the medullary raphe contributes to both the arousal process during hypoxia and to spontaneous “awakenings.” But these data provided little information about the contribution of specific receptors or neurons of a specific phenotype. Local application of nipecotic acid, however, which blocks the reuptake of GABA, also increased arousal latency, indicating that increases in ambient GABA locally in the medullary raphe also prolongs arousal during hypoxia. Finally, blockade of GABAA receptors with bicuculline abolished the progressive lengthening of arousal latency (habituation), indicating that GABAA receptors are involved in arousal habituation (18). The results of the current experiments show that medullary raphe 5-HT neurons also contribute to arousal in response to hypoxia. In these experiments, we did not study the effects of localized destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons on sleep architecture or the frequency of spontaneous awakenings.

DHT specifically destroys 5-HT neurons when desipramine blocks noradrenergic neuron uptake of the neurotoxin. We cannot be entirely sure that all noradrenergic neurons were protected against destruction with DHT, but the evidence from our own (12, 16) and other laboratories (5, 6) suggest that this is unlikely. In addition, all treatment groups were given desipramine, which should have controlled for any effects of desipramine alone in our experiments.

Serotonergic neuronal loss has been described as early as 1 day following CM administration in postnatal rat pups (57, 58). In other studies in rat pups in our laboratories, losses of TPH-immunopositive neurons in the RO and RM were evident when DHT was administered into the CM (12). Although we did not detect an effect of CM administration of DHT in the dorsal or median raphe nuclei or raphe pallidus, it would be difficult to completely rule out the potential for alterations in their function in these regions. Notably, however, pups that lacked a confirmed loss of 5-HT neurons in the RM did not exhibit the arousal deficit exhibited by pups with confirmed loss of 5-HT neurons. This observation, taken together with our previous work using local microinjections, argues for the importance of the medullary raphe in the current results.

Although not specifically counted in our analysis, 5-HT neurons in the DHT group were also eliminated lateral to the midline, a region that likely includes the parapyramidal and/or the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (PGCL). Ascending axons from these regions project to higher brain areas important for arousal, including the locus coeruleus. Descending projections to the spinal cord from the PGCL also influence motor activity, including during sleep. The longer arousal latency might be in part attributable to removal of the influence of these reticular 5-HT neurons on arousal mechanisms (16).

In the youngest pups, body temperature did not increase over the course of repeated hypoxia exposures as rapidly in the DHT or the IC pups compared with the aCSF pups. Medullary raphe 5-HT neurons contribute to the sympathetic outflow to brown adipose tissue (BAT), a tissue which is highly metabolic and of major importance for increasing heat production during cooling. Even though our chambers were maintained at near-thermoneutral temperatures, body temperature generally increased across the four trials of hypoxia. Loss of medullary 5-HT neurons may have contributed to the attenuated increase in temperature in the youngest DHT pups, which would have involved an increase in BAT heat production. However, this also occurred in IC pups that were injected with DHT but did not demonstrate 5-HT neuronal loss in the RM. Serotonergic neurons, mostly in the raphe pallidus, project to the IML of the spinal cord, where they influence sympathetic outflow to BAT (43). Although the raphe pallidus appeared to be relatively spared with respect to the effects of DHT, undoubtedly some 5-HT neurons were eliminated in this region, which may explain why thermoregulation was affected both in the DHT and the IC pups.

The exact stimulus causing arousal during hypoxia is not certain, but may be related to chemosensory and/or mechano-sensory activity, or to increases in ventilatory drive (4, 18). Exposure to hypoxia leads to increases in respiratory frequency and tidal volume, heart rate, and blood pressure in adult and developing mammals. The carotid bodies initiate the augmentation in ventilation largely through synapses in the solitary nucleus (NTS) and further projections to populations of neurons involved in respiratory control. How sensory input travels from the NTS to the medullary raphe remains unclear.

It has been previously shown that hypoxia-induced fH and ventilatory responses to CO2 are not significantly altered in very young rat pups (<P5) after CM injections of DHT (12), arguing against a heart rate response deficit as a cause of the arousal delay during hypoxia in 5-HT lesioned pups. Our study partially corroborated those findings in that the fH response to hypoxia was not affected by DHT treatment. Unexpectedly, however, pups in the IC group that did not demonstrate a significant reduction in the numbers of 5-HT neurons in the RM after DHT treatment had higher baseline fH than the other groups, especially at P25, and at this age hypoxia resulted in a decrease rather than an increase in fH. The reason for the increased baseline heart rate in the IC group is unclear, but it could possibly be related to destruction or damage to 5-HT neurons lateral to the midline raphe that were not specifically counted or observed that may be involved in the regulation of heart rate.

On the other hand, the blunted rates of increase in fR from the onset of hypoxia to arousal that we observed in the DHT-treated pups suggest that fR responses to hypoxia were compromised after destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons. Destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons did not alter the inverse relationship between the slope of the fR response and arousal latency, suggesting that the fR response to hypoxia is linked to arousal but that a change in this relationship was not responsible for the effect of DHT treatment. Our findings do suggest that 5-HT neurons in the raphe magnus/obscuris participate in the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Serotonergic and non-5-HT neurons located in the population of cells established by the transcription factor, “early growth response2” (Egr2), play a major role in the ventilatory response to CO2 (49). The 5-HT neurons in this population lie in the more rostral part of the medullary raphe, corresponding roughly to the RM and obscurus. Our findings suggest that this population of neurons may also be involved in the ventilatory response to hypoxia.

Treatment with DHT did not affect baseline or prehypoxia fR. Pet1−/− mice lacking 70% of functional 5-HT neurons (involving all serotonergic nuclei) from the time of conception do have a decrease in resting fR compared with wild type controls, but a normal minute ventilation when normalized to metabolic rate (13). However, recent studies in our laboratories using a 5,7,DHT model similar to the one used in the current study also showed no decrease in resting fR compared with control aCSF injected pups (14). One can speculate on the reason, but it may be related to the timing of the defect (at conception for the PET1−/− and early postnatal life for the 5,7-DHT experiments) or the relative severity of the 5-HT lesion, being less severe and localized to certain nuclei within the caudal medulla in the 5,7-DHT pups and more generalized in the PET1−/− mice.

Loss of medullary 5-HT neurons may have a major effect on the motor components of arousal. Serotonergic raphe-spinal projections facilitate both somatic motor activity (39) and increase respiratory output (20). Depletion of 5-HT after systemic administration of parachlorophenylalanine (PCPA) in very young rodents (P0–P5) decreases the excitability of motor neurons innervating ankle flexor muscles, leading to postural instability (47). Loss of such facilitation on descending motor components of arousal, or the effect of an early loss of 5-HT on motor network development, might contribute to the DHT effects on arousal latency. A startle accompanied by an augmented breath is the earliest component of the arousal response in human infants given a respiratory arousal stimulus (38, 42). Startles consist of sudden motions of the neck and spine, followed by slower thrashing movements, including head lifting and turning. Neonatal rats and mice show similar types of activity during arousal to respiratory stimuli (17, 19, 23). Head lifting and turning are particularly important as they may allow an infant to move out of a potentially asphyxiating environment.

Arousal latencies were longer after DHT treatment mostly at P5 and P25, whereas the effect of DHT on arousal latency was less apparent at P15. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear. An arousal prolongation after DHT treatment at P5 suggests that 5-HT synapses are functional at this postnatal age. Sleep architecture and cardiorespiratory responses to hypoxia change over the time period studied and interactions with the effects of 5-HT neuron destruction might explain effects at some ages and not others. Other studies have revealed age-dependent deficits in rat pups with 5-HT deficiencies. In young rats treated with CM DHT, locomotor activity was increased at P14 but decreased at P25 (8). In another study, V̇e and fR were decreased by DHT at P5 but not at P10-12, but the decreases in V̇e in the younger pups was proportional to a decrease in V̇o2, resulting in no change in V̇e/V̇o2 (12). In addition, P5, P15, and P25 rat pups with low brain 5-HT concentrations resulting from maternal dietary tryptophan restriction have lower V̇e and V̇e/V̇o2 at P25 compared with the other ages (46). In our study arousal latencies were shortest and there was a greater slope of the fR response to hypoxia at P15 compared with the latencies and fR responses at either P5 or P25. Thus an increase in motor activity or a more robust ventilatory response to hypoxia at this developmental age may have masked an otherwise depressive effect of DHT on arousal.

Although we did not systematically examine sleep architecture in this study, we did make note of sleep transitions from QS to AS by using behavioral criteria. Since the response latency to arousal stimuli in young mammals is often longer in AS compared with QS (18), an increase in AS time or frequency would be expected to lengthen arousal latency. In this study, similar to our previous results (17), pups transitioned to AS before arousal almost 100% of the time at P5, ∼70% of the time at P15, and none of the time at P25. Importantly, there was no difference in the propensity to transition to AS before arousal between the DHT, IC, and aCSF groups.

Buchanan and Richerson (10) studied arousal in response to CO2 and hypoxia in adult mice hemizygous for ePet1-Cre and homozygous for floxed Lmx1b, a strain with a total absence of 5-HT neurons. In these adult mice, there were no effects on arousal to a hypoxic stimulus, but the arousal response to hypercapnia was deficient. There was also increased activity and wakefulness in a cool environment, but there was normal sleep architecture at thermoneutrality. They proposed that these 5-HT KO mice increase their activity to raise body temperature when the environment is subthermoneutral. In contrast, arousal in response to hypoxia was impaired in our rat pups after acute destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons. Our experiments were also carried out at thermoneutrality, and therefore we would not expect a thermoregulatory process, such as increased activity in cooler temperatures, to impact arousal latency.

Although the mechanisms through which medullary 5-HT neurons contribute to arousal remain undefined, it seems likely that abrupt arousal from sleep in response to a respiratory stimulus would be associated with an increase in serotonergic neuronal activity. The activity of serotonin neurons in both the medullary and mesopontine raphe nuclei is state dependent, with high levels of activity during wakefulness, less activity during NREM sleep, and very little activity during REM (31, 50). Moreover, the firing rates of RO and raphe pallidus 5-HT neurons increase during spontaneous movements in the cat and during increases in ventilation (55). However, our observation that destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons did not affect arousal habituation, suggests that 5-HT, unlike GABAergic, mechanisms are not involved in this process.

In summary, destruction of medullary 5-HT neurons resulted in arousal impairment and a blunted respiratory frequency response to repeated episodes of hypoxia in developing rodents. Whereas body weight increased at a slower rate after DHT treatment, baseline cardiorespiratory measures were not different from controls, with a modest decrease in metabolic rate prior to arousal testing in the older pups. The cardiorespiratory responses to hypoxia were largely intact in the DHT-lesioned animals. However, augmentation of respiratory frequency was reduced with medullary 5-HT cell loss. Our results indicate that medullary 5-HT neurons contribute to normal arousal and respiratory frequency responses to hypoxia encountered in sleep. We speculate that in some SIDS infants, deficiencies in 5-HT function may contribute to impaired arousal, which, in turn, may contribute to their death.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant PO1 HD-036379.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.A.D. and R.W.S. conception and design of research; R.A.D., R.W.S., C.M.T., and K.G.C. analyzed data; R.A.D., R.W.S., and K.G.C. interpreted results of experiments; R.A.D. and K.G.C. prepared figures; R.A.D. drafted manuscript; R.A.D., R.W.S., and K.G.C. edited and revised manuscript; R.A.D., R.W.S., and K.G.C. approved final version of manuscript; C.M.T. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hannah Kinney and the SIDS Program Project group for inspiration and Dr. Donald Bartlett and Dr. Eugene Nattie for comments on the manuscript.

All work was completed at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

Present address for C. M. Tobia, 9402 120th Ave., Grande Prairie, Alberta, Canada, T8V4R3; for R. W. Schneider, University of Vermont College of Medicine, Health Science Research Facility 440, Burlington, VT 05405.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GW, Schoonover CM, Jones SA. Control of thyroid hormone action in the developing rat brain. Thyroid 13: 1039–1046, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balbir A, Lande B, Fitzgerald RS, Polotsky V, Mitzner W, Shirahata M. Behavioral and respiratory characteristics during sleep in neonatal DBA/2J and A/J mice. Brain Res 1241: 84–91, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer SA, Altman J, Russo RJ, Zhang X. Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neurotoxicology 14: 83–144, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry RB, Gleeson K. Respiratory arousal from sleep: mechanisms and significance. Sleep 20: 654–675, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorklund A, Baumgarten HG, Lachenmayer L, Rosengren E. Recovery of brain noradrenaline after 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine-induced axonal lesions in the rat. Cell Tissue Res 161: 145–155, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorklund A, Baumgarten HG, Rensch A. 5,7-Dihydroxytryptamine: improvement of its selectivity for serotonin neurons in the CNS by pretreatment with desipramine. J Neurochem 24: 833–835, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg MS, Seelke AM, Lowen SB, Karlsson KA. Dynamics of sleep-wake cyclicity in developing rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 14860–14864, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breese GR, Vogel RA, Mueller RA. Biochemical and behavioral alterations in developing rats treated with 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 205: 587–595, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JW, Sirlin EA, Benoit AM, Hoffman JM, Darnall RA. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in medullary raphe disrupts sleep and decreases shivering during cooling in the conscious piglet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R884–R894, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan GF, Richerson GB. Central serotonin neurons are required for arousal to CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 16354–16359, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conklin P, Heggeness FW. Maturation of tempeature homeostasis in the rat. Am J Physiol 220: 333–336, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings KJ, Commons KG, Fan KC, Li A, Nattie EE. Severe spontaneous bradycardia associated with respiratory disruptions in rat pups with fewer brain stem 5-HT neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1783–R1796, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings KJ, Commons KG, Hewitt JC, Daubenspeck JA, Li A, Kinney HC, Nattie EE. Failed heart rate recovery at a critical age in 5-HT-deficient mice exposed to episodic anoxia: implications for SIDS. J Appl Physiol 111: 825–833, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings KJ, Hewitt JC, Li A, Daubenspeck JA, Nattie EE. Postnatal loss of brainstem serotonin neurones compromises the ability of neonatal rats to survive episodic severe hypoxia. J Physiol 589: 5247–5256, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danneman PJ, Mandrell TD. Evaluation of five agents/methods for anesthesia of neonatal rats. Lab Anim Sci 47: 386–395, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darnall RA, Harris MB, Gill WH, Hoffman JM, Brown JW, Niblock MM. Inhibition of serotonergic neurons in the nucleus paragigantocellularis lateralis fragments sleep and decreases rapid eye movement sleep in the piglet: implications for sudden infant death syndrome. J Neurosci 25: 8322–8332, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darnall RA, McWilliams S, Schneider RW, Tobia CM. Reversible blunting of arousal from sleep in response to intermittent hypoxia in the developing rat. J Appl Physiol 109: 1686–1696, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darnall RA, Schneider RW, Tobia CM, Zemel BM. Arousal from sleep in response to intermittent hypoxia in rat pups is modulated by medullary raphe GABAergic mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R551–R560, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dauger S, Aizenfisz S, Renolleau S, Durand E, Vardon G, Gaultier C, Gallego J. Arousal response to hypoxia in newborn mice. Respir Physiol 128: 235–240, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Depuy SD, Kanbar R, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Control of breathing by raphe obscurus serotonergic neurons in mice. J Neurosci 31: 1981–1990, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev 3: 79–83, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan JR, Paterson DS, Hoffman JM, Mokler DJ, Borenstein NS, Belliveau RA, Krous HF, Haas EA, Stanley C, Nattie EE, Trachtenberg FL, Kinney HC. Brainstem serotonergic deficiency in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 303: 430–437, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durand E, Lofaso F, Dauger S, Vardon G, Gaultier C, Gallego J. Intermittent hypoxia induces transient arousal delay in newborn mice. J Appl Physiol 96: 1216–1222; discussion 1196, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fournier S, Steele S, Julien C, Fournier S, Gulemetova R, Caravagna C, Soliz J, Bairam A, Kinkead R. Gestational stress promotes pathological apneas and sex-specific disruption of respiratory control development in newborn rat. J Neurosci 33: 563–573, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper RM. Impaired arousals and sudden infant death syndrome: preexisting neural injury? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 1262–1263, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harper RM, Richard CA, Henderson LA, Macey PM, Macey KE. Structural mechanisms underlying autonomic reactions in pediatric arousal. Sleep Med 3 Suppl 2: S53–56, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hobson JA, McCarley RW, Wyzinski PW. Sleep cycle oscillation: reciprocal discharge by two brainstem neuronal groups. Science 189: 55–58, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofer MA, Reiser MF. The development of cardiac rate regulation in preweanling rats. Psychosom Med 31: 372–388, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horne RS, Parslow PM, Ferens D, Bandopadhayay P, Osborne A, Watts AM, Cranage SM, Adamson TM. Arousal responses and risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome. Sleep Med 3 Suppl 2: S61–65, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev 72: 165–229, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs BL, Martin-Cora FJ, Fornal CA. Activity of medullary serotonergic neurons in freely moving animals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 40: 45–52, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlsson KA, Blumberg MS. The union of the state: myoclonic twitching is coupled with nuchal muscle atonia in infant rats. Behav Neurosci 116: 912–917, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinney HC, Richerson GB, Dymecki SM, Darnall RA, Nattie EE. The brainstem and serotonin in the sudden infant death syndrome. In: Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, edited by Abbas AK, Galli SJ, andHowley PM. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, 2009, p. 517–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knuth ED, Etgen AM. Neural and hormonal consequences of neonatal 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine may not be associated with serotonin depletion. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 151: 203–208, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagerspetz KY. Temperature relations of oxygen consumption and motor activity in newborn mice. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn 44: 71–73, 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leiter JC, Bohm I. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in the sudden infant death syndrome. Resp Physiol Neurobi 159: 127–138, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lighton JRB. Measuring Metabolic Rates: A Manual for Scientists. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lijowska AS, Reed NW, Chiodini BA, Thach BT. Sequential arousal and airway-defensive behavior of infants in asphyxial sleep environments. J Appl Physiol 83: 219–228, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Jordan LM. Stimulation of the parapyramidal region of the neonatal rat brain stem produces locomotor-like activity involving spinal 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A receptors. J Neurophysiol 94: 1392–1404, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maciag D, Simpson KL, Coppinger D, Lu Y, Wang Y, Lin RC, Paul IA. Neonatal antidepressant exposure has lasting effects on behavior and serotonin circuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 47–57, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarley RW, Hobson JA. Neuronal excitability modulation over the sleep cycle: a structural and mathematical model. Science 189: 58–60, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNamara F, Wulbrand H, Thach BT. Characteristics of the infant arousal response. J Appl Physiol 85: 2314–2321, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central neural pathways for thermoregulation. Front Biosci 16: 74–104, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mouroux I, Bertin R, Portet R. Thermogenic capacity of the brown adipose tissue of developing rats; effects of rearing temperature. J Dev Physiol 14: 337–342, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paterson DS, Trachtenberg FL, Thompson EG, Bellivieau RA, Beggs AH, Darnall R, Chadwick AE, Krous HF, Kinney HC. Multiple serotonergic brainstem abnormalities in the sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 296: 2124–2132, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penatti EM, Barina AE, Raju S, Li A, Kinney HC, Commons KG, Nattie EE. Maternal dietary tryptophan deficiency alters cardiorespiratory control in rat pups. J Appl Physiol 110: 318–328, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pflieger JF, Clarac F, Vinay L. Postural modifications and neuronal excitability changes induced by a short-term serotonin depletion during neonatal development in the rat. J Neurosci 22: 5108–5117, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portas CM, Thakker M, Rainnie D, McCarley RW. Microdialysis perfusion of 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) in the dorsal raphe nucleus decreases serotonin release and increases rapid eye movement sleep in freely moving cat. J Neurosci 16: 2820–2828, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Soriano LP, Nattie EE, Dymecki SM. Egr2-neurons control the adult respiratory response to hypercapnia. Brain Res 1511: 115–125, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakai K, Vanni-Mercier G, Jouvet M. Evidence for the presence of PS-OFF neurons in the ventromedial medulla oblongata of freely moving cats. Exp Brain Res 49: 311–314, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawaguchi T, Franco P, Groswasser J, Kahn A. Partial arousal deficiency in SIDS victims and noradrenergic neuronal plasticity. Early Hum Dev 75 Suppl: S61–64, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seelke AM, Blumberg MS. The microstructure of active and quiet sleep as cortical delta activity emerges in infant rats. Sleep 31: 691–699, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seelke AM, Karlsson KA, Gall AJ, Blumberg MS. Extraocular muscle activity, rapid eye movements and the development of active and quiet sleep. Eur J Neurosci 22: 911–920, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor NC, Li A, Nattie EE. Medullary serotonergic neurones modulate the ventilatory response to hypercapnia, but not hypoxia in conscious rats. J Physiol 566: 543–557, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veasey SC, Fornal CA, Metzler CW, Jacobs BL. Response of serotonergic caudal raphe neurons in relation to specific motor activities in freely moving cats. J Neurosci 15: 5346–5359, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wainwright PE, Leatherdale ST, Dubin JA. Advantages of mixed effects models over traditional ANOVA models in developmental studies: a worked example in a mouse model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Dev Psychobiol 49: 664–674, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker PD, Wolf WA. Alterations in the postnatal development of striatal preprotachykinin but not preproenkephalin mRNA expression in the serotonin-depleted rat. Dev Neurosci 19: 135–142, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waller SB, Buterbaugh GG. Tonic convulsive thresholds and responses during the postnatal development of rats administered 6-hydroxydopamine or 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine within three days following birth. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 19: 973–978, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waters KA, Tinworth KD. Habituation of arousal responses after intermittent hypercapnic hypoxia in piglets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 1305–1311, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Behavioral and cellular consequences of increasing serotonergic activity during brain development: a role in autism? Int J Dev Neurosci 23: 75–83, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zorrilla EP. Multiparous species present problems (and possibilities) to developmentalists. Dev Psychobiol 30: 141–150, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]