Introduction

In-house call is an important component of orthopedic surgery residency, with a significant portion of the post-graduate year (PGY)-2 and PGY-3 duties devoted to 24-h clinical shifts in the hospital. A majority of this time is spent attending to the needs of pre- and post-operative patients and responding to emergency department (ED) and inpatient consultations—activities that demand priority over non-clinical endeavors. However, there is occasionally time available for other pursuits such as research, study, sleep, and exercise.

A variety of publications have demonstrated the need to promote resident physical activity [1, 2, 5, 7, 12] and the beneficial effects it has on both the mental and physical well-being of the individual resident and his or her ability to provide high-quality clinical care [4, 11, 14]. In an effort to encourage resident fitness and improve patient care, an assortment of exercises were developed that can be performed while on-call using only repurposed supplies that are readily available in the hospital.

Equipment and exercises

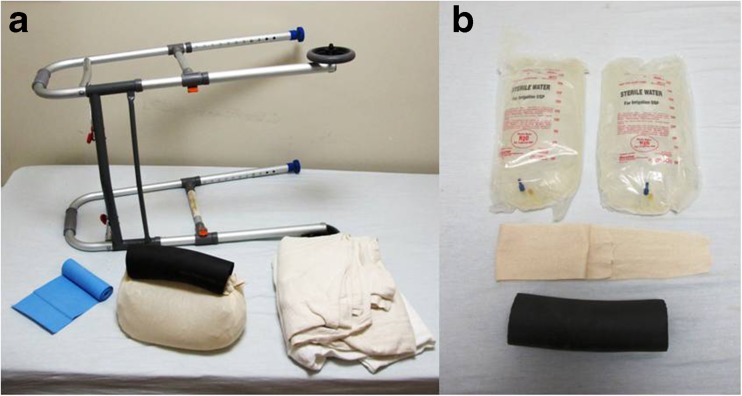

All of the materials used are familiar and accessible to an orthopedic resident (Fig. 1a, b). A makeshift kettlebell is a versatile piece of equipment that is assembled as follows (Fig. 1b): Two 3-L irrigation bags (sterile water, Baxter International Inc., Deerfield, IL) are placed in a 6-in. stockinette (Medline Industries Inc., Mundelein, IL), which is tied on each end. The remaining slack in the stockinette is fed through perineal post-foam (Armacell AP/Armaflex Microban 25/50, Armacell International Holding GmbH, Münster, Germany). If additional weight is desired, a 20-lb weight bag (Vinyl Water Bag, Freeman Manufacturing Co., Sturgis, MI) such as that typically used for skeletal traction can be used in place of irrigation bags. The kettlebell can be used for a variety of exercises, including swings (Fig. 2a, b), biceps curls (Fig. 2c, d), triceps extensions (Fig. 2e, f), and shoulder shrugs (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Orthopedic resident on-call workout equipment featuring an assembled a kettlebell and b component parts.

Fig. 2.

Selection of kettlebell exercises—a, b swings; c, d biceps curls; and e, f triceps extensions.

Table 1.

Example workout

| Exercise | Equipment | Setsa |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder circles | Esmarch | 25 each direction, each arm |

| Internal rotation pulls | Esmarch | 25 each arm |

| External rotation pulls | Esmarch | 25 each arm |

| Empty cans | Esmarch or kettlebell | 25 each arm |

| Dips | Walker | 10 |

| Squats | Esmarch or kettlebell | 15 |

| Leg raises | Walker | 10 |

| Biceps curls | Esmarch or kettlebell | 20 each arm |

| Triceps extensions | Esmarch or kettlebell | 20 each arm |

| Seated row | Esmarch, chair | 25 |

| Kettlebell swings | Kettlebell | 20 |

| Latissimus dorsi pull downs | Esmarch | 15 |

| Push-ups | Blanket | 20 |

| Crunches | Blanket | 30 |

| Stair climbs | Stairwell | 10 flights |

aPerform entire workout three times over the course of an in-house call

A walker (Medline Industries Inc., Mundelein, IL) is used for suspended upper extremity exercises. For example, dips (Fig. 3a, b) and shoulder shrugs are easily executed. Additionally, core exercises, including L-sits (Fig. 3c) and suspended leg raises may be performed.

Fig. 3.

a, b Dips and c an L-sit demonstrated on a walker.

An Esmarch bandage (Sklar Surgical Instruments, West Chester, PA) supplants therapy bands for the on-call resident. The Esmarch may be tied to a door handle for exercises that stabilize the rotator cuff such as shoulder circles, resisted internal rotation, and resisted external rotation (Fig. 4a, b). Seated rows may be performed sitting in a chair (Fig. 4c, d). Standing on the mid-portion of the Esmarch bandage provides balanced bilateral resistance for biceps curls, shoulder shrugs, resisted empty cans, lateral raises (Fig. 4e, f), and lower extremity squats. The Esmarch can be applied over the shower bar of the call room bathroom for latissimus dorsi pull downs (Fig. 4g, h).

Fig. 4.

Examples of exercises performed with an Esmarch bandage—a, b external rotation pulls; c, d seated rows; e, f lateral raises; and g, h latissimus dorsi pull downs.

Abdominal crunches, push-ups, and general stretching are performed on a blanket laid on the call room floor. To round out a comprehensive workout, the resident may consider stair-climbing or running in a hospital stairwell to maximize lower extremity conditioning and cardiovascular endurance.

Discussion

It is widely accepted that frequent exercise has a myriad of positive effects on both mental and physical health and is beneficial in the prevention of chronic disease [3]. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has mandated that residency programs take actions to minimize resident fatigue and burnout in order to optimize patient safety [10]. Regular resident exercise is an intervention that may complement ACGME compliance efforts. However, even with a work week limited to 80-h [10], residents may find it difficult to routinely dedicate their free time to exercise.

Multiple studies have shown that residents have lower levels of physical activity and general wellness [2], even when compared to medical students and attending physicians [1]. A 2010 investigation found that resident physicians had significantly lower bone mineral density (BMD) than healthy controls, with inadequate physical activity significantly correlated with diminished BMD [7]. Furthermore, resident fitness appears to decline over the course of residency, with residents more likely to be overweight (body mass index ≥25 kg/m2) at beginning of PGY-3 year than at beginning of PGY-1 year (49 versus 30%, odds ratio 2.26, 95% confidence interval 1.19–4.28) [5].

Resident inactivity, poor health, and burnout are not inevitable outcomes for residents. Weight et al. [14] demonstrated that implementation of a regular exercise program resulted in a significant increase in resident quality of life and a trend toward decreased levels of burnout. Similarly, Lebensohn et al. [4] used an online questionnaire to survey resident physicians and discovered that exercise was one of the behaviors most associated with higher levels of general well-being. These benefits may directly improve patient care, with regular resident exercise resulting in a significant increase in residents’ confidence in and perceived success of patient exercise counseling as well as a trend toward increased frequency of such counseling interventions [11].

Nemani et al. [9] recently reviewed the qualities displayed by exemplary orthopedic residents; these included important factors such as trustworthiness, efficiency, and professionalism. However, notably absent from this list was physical fitness. In 2011, Subramanian et al. [13] found that a cohort of orthopedic surgeons were physically stronger than their anesthesia colleagues. The authors speculated that this observed difference was attributable to the physical requirements necessary to perform orthopedic surgery [13]. Whether in the operating room or in the ED, many of the tasks inherent to orthopedic surgery require some degree of muscle strength (e.g., reducing dislocated prosthetic joints and inserting surgical implants), which could be cultivated during down-time in on-call periods.

The collection of fitness equipment and exercises presented here can be combined in a myriad of ways to produce a well-rounded on-call workout. An example workout is provided in the Table 1. Note that the assigned repetitions for each exercise are suggested numbers only and can be modified to match the fitness and strength level of the participant. Furthermore, the sample program is neither gender- nor specialty-specific, but it can easily be tailored to address individual needs and goals. Proper pre- and post-workout stretching and warm-up is suggested [6]. Residents may subdivide their workout into shorter segments performed over the course of the day if on-call responsibilities do not permit completing a full workout in a single session. Evidence suggests that multiple short bouts of exercises confer health benefits similar to a single continuous session [8].

The assortment of exercises presented by no means represents a comprehensive list, and residents should be encouraged to explore their available supplies and facilities to devise an armamentarium of fitness resources. Caution must be employed when selecting these materials as they are typically hospital property and should be either acquired once otherwise slated for disposal or returned in mint condition at the conclusion of the workout. Even in the absence of such supplies, a broad array of exercises can be performed with no equipment whatsoever (e.g., lunges and jumping jacks). However, the authors found fabrication of workout apparatus to be an enjoyable activity that encouraged exercise participation. The addition of relatively inexpensive commercial equipment, including a door-mounted pull-up bar (Complete Chin Up Bar, Astone Fitness, Richmond, BC, Canada) and a dip station (P-245 Dip Bars, Atlantis Inc., Laval, Quebec, Canada) may also be considered to increase the effectiveness and variety of an on-call workout regimen.

A diverse assortment of exercises can be performed while in the hospital. Even if workouts are spread over fragmented, short sessions of free time, such as those available to on-call orthopedic surgery residents, significant health benefits can be achieved. Furthermore, enhancing resident access to physical activity improves their well-being and ability to provide high-quality patient care. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper to formally propose a workout regimen specifically designed for the on-call resident. By making a case for the potential benefits of on-call workouts and presenting a sample fitness routine, we hope to inspire further research to quantify the effects of on-call exercise.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 526 kb)

(PDF 526 kb)

(PDF 526 kb)

Disclosures

Conflict of Interest

Peter B. Derman, MD, MBA, Joseph Liu, MD, and Alexander S. McLawhorn, MD, MBA have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Human/Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is not applicable for this article.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Hull SK, DiLalla LF, Dorsey JK. Prevalence of health-related behaviors among physicians and medical trainees. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Resid Train Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):31–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josephson EB, Caputo ND, Pedraza S, Reynolds T, Sharifi R, Waseem M, et al. A sedentary job? Measuring the physical activity of emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laskowski ER, Lexell J. Exercise and sports for health promotion, disease, and disability. PM R. 2012;4(11):795–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.09.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebensohn P, Dodds S, Benn R, Brooks AJ, Birch M, Cook P, et al. Resident wellness behaviors: relationship to stress, depression, and burnout. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):541–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leventer-Roberts M, Zonfrillo MR, Yu S, Dziura JD, Spiro DM. Overweight physicians during residency: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):405–11. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00289.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Micheo W, Baerga L, Miranda G. Basic principles regarding strength, flexibility, and stability exercises. PM R. 2012;4(11):805–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.09.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Multani SK, Sarathi V, Shivane V, Bandgar TR, Menon PS, Shah NS. Study of bone mineral density in resident doctors working at a teaching hospital. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56(2):65–70. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.65272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy MH, Blair SN, Murtagh EM. Accumulated versus continuous exercise for health benefit: a review of empirical studies. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 2009;39(1):29–43. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nemani VM, Park C, Nawabi DH. What makes a “great resident”: the resident perspective. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014; 7(2): 164-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT, ACGME Work Group on Resident Duty Hours Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288(9):1112–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers LQ, Gutin B, Humphries MC, Lemmon CR, Waller JL, Baranowski T, et al. A physician fitness program: enhancing the physician as an “exercise” role model for patients. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17(1):27–35. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1701_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, Powell CK, Poston MB, Stallworth JR. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360–4. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanian P, Kantharuban S, Subramanian V, Willis-Owen SAG, Willis-Owen CA. Orthopaedic surgeons: as strong as an ox and almost twice as clever? Multicentre prospective comparative study. BMJ. 2011;343:d7506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weight CJ, Sellon JL, Lessard-Anderson CR, Shanafelt TD, Olsen KD, Laskowski ER. Physical activity, quality of life, and burnout among physician trainees: the effect of a team-based, incentivized exercise program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1435–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 526 kb)

(PDF 526 kb)

(PDF 526 kb)