Abstract

Triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cell-1 (TREM-1) is a superimmunoglobulin receptor expressed on myeloid cells. Synergy between TREM-1 and Toll-like receptor amplifies the inflammatory response; however, the mechanisms by which TREM-1 accentuates inflammation are not fully understood. In this study, we investigated the role of TREM-1 in a model of LPS-induced lung injury and neutrophilic inflammation. We show that TREM-1 is induced in lungs of mice with LPS-induced acute neutrophilic inflammation. TREM-1 knockout mice showed an improved survival after lethal doses of LPS with an attenuated inflammatory response in the lungs. Deletion of TREM-1 gene resulted in significantly reduced neutrophils and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, particularly IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. Physiologically deletion of TREM-1 conferred an immunometabolic advantage with low oxygen consumption rate (OCR) sparing the respiratory capacity of macrophages challenged with LPS. Furthermore, we show that TREM-1 deletion results in significant attenuation of expression of miR-155 in macrophages and lungs of mice treated with LPS. Experiments with antagomir-155 confirmed that TREM-1-mediated changes were indeed dependent on miR-155 and are mediated by downregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) a key miR-155 target. These data for the first time show that TREM-1 accentuates inflammatory response by inducing the expression of miR-155 in macrophages and suggest a novel mechanism by which TREM-1 signaling contributes to lung injury. Inhibition of TREM-1 using a nanomicellar approach resulted in ablation of neutrophilic inflammation suggesting that TREM-1 inhibition is a potential therapeutic target for neutrophilic lung inflammation and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Keywords: TREM-1, lung injury, miR-155, nanomedicine

the prognosis of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) continues to be abysmal with mortality rates ranging from 30 to 40% (38, 39). Hence, ARDS represents an unmet medical need and there is an urgent need to develop new therapies to treat patients with this condition. Because of the complex nature of the disease, blocking of individual proinflammatory cytokines with antibodies or use of antioxidants has not been rewarding (5, 11). Therefore, understanding the contribution of proximal signaling pathways that amplify the inflammatory response and developing targeted therapies to specifically block them is an attractive approach to limit injury and inflammation for this devastating disease.

Triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) proteins are a family of immunoglobulin cell surface receptors expressed on myeloid cells. TREM-1 was the first TREM identified, and initial studies established TREM-1 as an amplifier of inflammatory response in sepsis (2, 3, 33). Upon ligation TREM-1 associates with an aspartate residue in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the adaptor protein DNAX activation protein 12 (DAP-12), leading to its tyrosine phosphorylation. This in turn results in downstream signal transduction events, which include the phosphorylation of phospholipase C and extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)-1/2 and tyrosine phosphorylation of adaptor molecules, such as growth factor receptor binding protein 2 with an increase in intracellular calcium and proinflammatory cytokine secretion through activation of NF-κB (7, 10, 44, 47).

The observation that TREM-1 is an amplifier of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-induced inflammation led to studies of TREM-1 in animal models of sepsis, cecal ligation puncture, viral infection, and zymosan-induced hepatic granuloma models (3, 30). Blockade of TREM-1 has been shown to improve survival in animal models of sepsis (12–18, 31). In humans with sepsis, it has been shown that the levels of soluble component shed from the cell surface (sTREM-1) can be a marker of severity and prognosis (12). In addition, in human sepsis, TREM-1 activation occurs in inflammatory bowel disease (36), pancreatitis (22, 49), gout, and rheumatoid arthritis (26, 32). However, the role of TREM-1 in ARDS or acute neutrophilic lung injury has not been established.

Here we investigated the effects of TREM-1 deletion in a mouse model of LPS-induced lung injury. Deletion of the TREM-1 gene improved survival in a lethal model of neutrophilic lung injury with attenuation of inflammation. Physiologically TREM-1 knockout macrophages showed an immunometabolic advantage with a low oxygen consumption rate (OCR) with sparing of respiratory capacity. Furthermore, we show that the proinflammatory effects of TREM-1 are mediated by induction of microRNA (miR)-155. Inhibition of TREM-1 using a nanomicellar approach resulted in ablation of neutrophilic inflammation. These data for the first time show that TREM-1 accentuates proinflammatory response by increasing the expression of miR-155 in macrophages and suggest a novel mechanism by which TREM-1 signaling contributes to the lung injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

Male wild-type C57BL/6J mice (6–8 wk, weighing 20–30 g) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. TREM-1/3-deficient mice were obtained from Washington University at St. Louis. For the lung injury model, mice were randomly grouped and treated with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Escherichia coli 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich; 10 mg/kg diluted in 0.1 ml of PBS) by intraperitoneal or aerosolized LPS (1 mg/ml) as described previously (41). Control animals received vehicle (PBS) respectively. For survival studies, mice (25 mg/kg LPS ip) were monitored every 2 h and killed when moribund or after the observations were terminated. The above studies were approved by the Animal Care Committee and Institutional Biosafety Committee of the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and total and differential cell counts.

After mice were asphyxiated with CO2, tracheas were cannulated, and lungs were lavaged in situ with sterile pyrogen-free physiological saline that was instilled in four 1-ml aliquots and gently withdrawn with a 1-ml tuberculin syringe. Lung lavage fluid was centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min. The supernatant was kept at −70°C, the cell pellet was suspended in serum-free RPMI 1640, and total cell counts were determined on a grid hemocytometer. Differential cell counts were determined by staining cytocentrifuge slides with a modified Wright stain (Diff-Quik; Baxter) and counting 400–600 cells in complete cross sections.

Cell culture and treatment.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were prepared as described previously (41, 53). Briefly, cellular material from femurs of mice ranging from 8 to 16 wk of age was cultured in 10% L929 cell-conditioned medium. A murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, MD] was maintained in DMEM (Cellgro) containing 10% FBS (Hyclone) and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml; Invitrogen). Cells were transfected with antagomirs against miR-155-5p and miR-155-3p (100 nmol/l), mirVana miRNA Inhibitor Negative Control (100 nmol/l), miR-155-3p mimic (100 nmol/l), and mirVans miRNA mimic Negative Control (100 nmol/l; Life Technologies) through a specific Lonza transfection reagent (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated with RNA complexes for 48–72 h before analysis. For in vitro experiments, cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml). Control cells were treated with sterile PBS or control isotype IgG (10 ng/ml). The NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11–7082 (1 μmol/l) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Rat anti-TREM-1 antibody (AF1187) was purchased from R&D Systems.

Histology.

The images were acquired with the use of a light microscope. For mouse lungs tissue sections were stained for immunoperoxidase and standard hematoxylin-eosin, as described previously (53).

Preparation of RNA- and miRNA-quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated by mirVanaTM miRNA isolation kit (Life Technologies). Relative expression of miRNA was assayed via the TaqMan microRNA Assay (Life Technologies). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, using an ABI PRISM 7500 quantitative PCR apparatus (Life Technologies), and the expression values were normalized against the small housekeeping RNAs U6 snRNA. Comparative assessment of mRNA expression was performed as described previously (52), using TaqMan mRNA Assay (Life Technologies).

miRNA expression profile assay.

A microarray screen of miRs expression in the BMDM from wild-type and TREM-1/3-deficient mice was performed with the use of ORB MirBASE Version 19 MicroRNA Microarray (Ocean Ridge Bioscience). Quality control of the total RNA samples was assessed using UV spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis. The samples were DNAse digested, and low-molecular weight RNA was isolated, purified, labeled, and hybridized to the miRNA microarrays according to conditions recommended in the Flash Taq RNA Labeling Kit manual. The microarrays were scanned on an Axon Genepix 4000B scanner, and data were extracted from images using GenePix V4.1 software. Spot intensities were obtained for the 1,280 mouse miRNAs on each microarray by subtracting the median local background from the median local foreground for each spot, and then log2-transformed spot intensities for all features were normalized. The top 50 LPS-induced genes were chosen for heatmap analysis using Matrix2png software.

Metabolic flux assay.

The bioenergetic flux of cells in response to LPS, miR155 mimic, or TREM-1 silencing was assessed using the Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences). The XF cell mito stress kit (Seahorse Biosciences) was used to measure OCR. A 96-well XF sensor cartridge plate containing XF calibration buffer (200 μl/well) was calibrated overnight at 37°C, CO2-free incubator. For LPS treatment, the indicated cells were plated at 2 × 104 cells per well in XF96 plates, incubated overnight, and then treated with either vehicle or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h. The medium was then replaced with unbuffered DMEM XF assay medium (pH 7.4) supplemented with 2 mmol/l glutamine and 1 g/l glucose and incubated at 37°C, in a CO2-free incubator, for at least 30 min. For TREM-1 silencing and miR-155-3p overexpression, the indicated cells were transfected with TREM-1 siRNA or control siRNA, or miR-155-3p mimic and mirVana miRNA Mimic Negative Control, and then cells were plated at 2 × 104 cells per well in XF96 plates and incubated with DMEM/F12 regular cell culture medium in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C overnight. The medium was then replaced with unbuffered DMEM XF assay medium as described above. After calibration of the XF sensor with a preincubated sensor cartridge pale, the cell plate was loaded into the XF96 analyzer. Compounds were injected into cells through a cartridge, according to following order: oligomycin (2 μmol/l), [carbonyl cyanide-p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone] (FCCP; 1 μmol/l), and rotenone/antimycin (1 μmol/l). OCR and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were then determined on the XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Data with 12 replicates of each group were analyzed using XF analytical software.

Preparation of LP17-loaded sterically stabilized phospholipid nanomicelles.

TREM-1 blocking peptide LP17 (LQVTDSGLYRCVIYHPP) and control peptide (TDSRCVIGLYHPPLQVY) were synthesized by Protein Research Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago (53). The peptide was HPLC purified, and the peptide purity was >90% as ascertained by RP-HPLC. Sterile saline (0.9% NaCl injection USP) was manufactured by Baxter Healthcare (Deerfield, IL). All other reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich. DSPE-PEG2000 {1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine -N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000]} was purchased from LIPOID (Ludwigshafen, Germany). TREM-1 in sterically stabilized phospholipid nanomicelles (SSM) was prepared as previously described in our laboratory (24, 25, 27). Briefly, a weighed amount of DSPE-PEG2000 was added to saline and vortexed for 2 min (Thermolyne Maxi Mix II) to form SSM at lipid concentrations above its critical micellar concentration (0.5–1 μmol/l). Composition of the optimized TREM-1-SSM formulation was found to be 5.0 mmol/l DSPE-PEG2000 with 50 μmol/l TREM-1. The dispersion was then incubated at 25°C for 1 h in the dark. Thereafter, a measured volume of TREM-1 stock solution (in saline) was added to SSM, and the resulting dispersion was further incubated for 2 h at 25°C in the dark. TREM-1-SSM (1, 2.5, and 5 mmol/l DSPE-PEG2000 and 50 μmol/l TREM-1) in a liquid state was evaluated for stability at different temperatures, suitable for storage specifically refrigeration (5°C) and room temperature (25°C). Visual appearance (color, clarity, and precipitation) and turbidity (A 360 nm) of the samples were evaluated. TREM-1-SSM dispersions stored at 5°C maintained clarity and transparency within the observation period (28 days of storage). Refrigerated TREM-1-SSM samples did not show any significant turbidity increase for up to 28 days. All analyzed TREM-1 -SSM formulations had monomodal particle size distribution with a mean particle size of 15.3 ± 2.0 nm determined by DLS (intensity-weighted Nicomp distribution), which were not significantly different from the blank SSM (15.1 ± 1.8 nmol). Drug-free “empty” SSM were prepared following the same procedure described above but excluding the addition of LP17.

Myeloperoxidase assay.

Lung samples were placed in 50 mmol/l K2HPO4 buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.5% hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide and stored at −80°C until used. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured as described previously (41, 51).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SE, unless specified. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software). All experiments were repeated at least three to five times. Student t-tests were used for two-group comparisons, ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests was used for multiple group comparisons, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Survival data were analyzed by the construction of Kaplan-Meier plots and use of log-rank test.

RESULTS

TREM-1 knockout mice show improved survival following lethal dose of LPS with attenuated lung inflammation and edema.

To define the role of TREM-1 in LPS-induced lung injury we performed mortality studies with LPS using a dose that has been shown to be lethal in mice (25 mg/kg). Wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice were administered intraperitoneal LPS (25 mg/kg) or PBS. As expected control wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice that received PBS all survived. Wild-type mice that received LPS, all succumbed within 96 h of LPS administration, whereas 80% of TREM-1 knockout mice survived the lethal dose of LPS (Fig. 1A). These data suggest that deletion of TREM-1 gene confers a survival advantage to lethal dose of LPS.

Fig. 1.

Triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cell-1 (TREM-1) knockout mice demonstrate improved survival with attenuated inflammation in response to LPS. A: wild-type (WT) and TREM-1 knockout mice were given 25 mg/kg of LPS or vehicle via intraperitoneal route. Control mice all survived. Wild-type mice treated with LPS all succumbed within 96 h whereas TREM-1 knockout mice showed an improved survival. The results are represented by Kaplan Meier curve; P < 0.01 log-rank test. B: lung histology from TREM-1 knockout mice shows an attenuation of neutrophilic influx compared with wild-type mice treated with LPS. HE, hematoxylin-eosin. C: bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell count showed significantly lower cell numbers in TREM-1 knockout mice. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assays from lungs (D), lung wet-to-dry ratio (W/D; E), BAL protein (F), TNF-α (G), IL-6 (H), and IL-1β (I) were lower in lungs of TREM-1 knockout mice. *P < 0.05; n = 5–6.

Next, we defined the effects of TREM-1 gene deletion on the lung edema and inflammation. In these experiments, wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice were challenged with aerosolized LPS (1 mg/ml) via a nebulizer, as described by us previously (27, 41). Mice were killed 12 h after aerosolized LPS. Lung histology showed that mice that received LPS had an influx of neutrophils, which was attenuated in TREM-1 knockout mice (Fig. 1B). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) also showed that the total and neutrophil counts and myeloperoxidase levels from lung tissue were significantly lower in TREM-1 knockout mice, compared with the wild-type mice (Fig. 1, C and D). The lung wet-to-dry ratio and total protein content of the lavage fluid, which are suggestive of lung edema and dysregulated barrier function, were also significantly lower in TREM-1 knockout mice (Fig. 1, E and F).

We have previously shown that the functional consequences of silencing TREM-1 gene in macrophages include an altered availability of key signaling (CD14, IκBα, and MyD88) and effector molecules (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) downstream of TLR activation (35). Therefore, we measured the levels of these cytokines in the lung tissue and BAL fluid from wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice treated with aerosolized LPS. TREM-1 knockout mice showed signficantly lower levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in lavage (Fig. 1, G, H, and I) and lungs (data not shown), compared with wild-type mice. Together these data show that deletion of TREM-1 gene improves survival in a lethal model of lung injury by attenuating the inflammatory response and lung edema.

Key miRNAs are altered by deletion of TREM-1 gene in macrophages.

Next, we wanted to investigate the mechanisms by which TREM-1 modulates the inflammatory response. miRs are short noncoding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally through base pairing with mRNAs, resulting in either translational repression or mRNA degradation, and thus regulate the expression of multiple genes at a posttranscriptional level. To date there is no information about TREM-1 signaling-mediated changes in miRNAs. Since our data shows that deletion of TREM-1 attenuates the levels of key effector molecules, we asked if these effects are mediated through modulation of miRNAs. To delineate if the TREM-1-induced inflammatory response was regulated my miRNAs, we treated macrophages from wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice with LPS or vehicle. Total RNA was extracted and miRNA expression was determined by using a microarray profile (MIR900) containing 1,280 matured mouse miRNA probes.

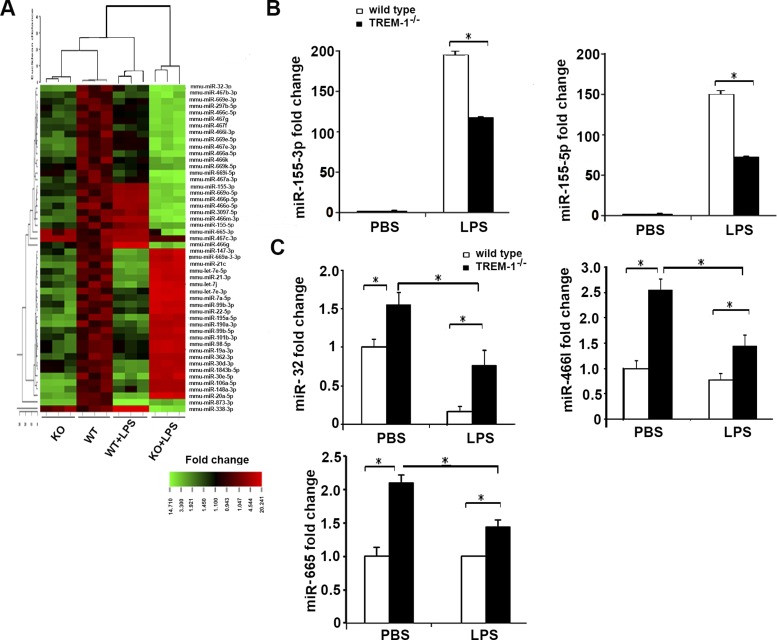

As shown in Fig. 2A, microarray data from TREM-1 knockdown macrophages showed altered expression of several miRNAs. In particular we found that expression of miR-155-3p and -5p, miR-32, miR-466l, and miR-665 was downregulated in TREM-1 knockout macrophages. We performed additional experiments and validated the expression of these miRNAs by performing RT-PCR and confirmed that miR-155-3p, 5p, miR-32, miR-466, and miR-665 were downregulated in TREM-1 knockout macrophages in response to LPS (Fig. 2, B and C). Collectively, these data show that signaling through TREM-1 modulates the expression of miRNAs particularly miR-155, which may in turn modulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 2.

Microarray analysis of miRNA expression from TREM-1 knockout (KO) and wild-type macrophages. Heat map of genes from TREM-1 and wild-type macrophages treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) (A). miR-155-3p and miR-155-5p (B) and miR-32, miR-466l, and miR-665 (C) were significantly downregulated in TREM-1 knockout macrophages. *P < 0.01; n = 4–5.

TREM-1-induced proinflammatory effects are mediated through miR-155.

Since miR-155 promotes inflammation (1, 6, 9, 29, 34, 48), we hypothesized that TREM-1 accentuates proinflammatory effects through miR-155. To investigate if the proinflammatory effects of TREM-1 are mediated by miR-155, we treated cells with mTREM-1 (monoclonal antibodies that specifically activate TREM-1) and miR-155 antagomirs. BMDM from wild-type mice were treated with mTREM-1(10 ng/ml) or IgG with and without antagomir against miR-155. Control cells were treated with mock antagomirs. Expression of miR-155 was detected by RT-PCR. Cells that were treated with mTREM-1 showed a significant increase in the expression of miR-155-3p compared with control cells that were treated with IgG. This increased expression of miR155 by mTREM-1 was suppressed by antagomir against miR-155 (Fig. 3A). Next, we wanted to investigate if the induction of proinflammatory cytokines by TREM-1 was dependent on miR-155. Macrophages were treated with mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml) with or without antagomir against miR-155. Cells treated with mTREM-1 showed a significant induction in TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA (Fig. 3, B–D). This induction was inhibited by treatment with antagomir against miR-155 (10 nmol/l). To define the contribution of miR-155 in vivo, we treated wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice with aerosolized LPS (1 mg/ml) and killed mice at 12 h after treatment as above. Total RNA from whole lung was extracted and quantitative RT-PCR was performed for miR-155-3p and miR-155-5p. We found that miR-155-3p and -5p were increased in wild-type mice treated with LPS, compared with saline-treated control mice. However, expression of miR-155-3p and -5p significantly decreased in lungs of TREM-1 knockout mice (Fig. 3E). These data for the first time show that the TREM-1-induced proinflammatory response is mediated by expression of miR-155 in macrophages and suggest a novel mechanism by which TREM-1 signaling contributes to lung injury.

Fig. 3.

Proinflammatory effects induced by TREM-1 are mediated through expression of miR-155. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from wild-type mice were treated with mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml) with or without antagomir against miR-155 (100 nmol/l). A: mTREM-1 induced the expression of miR-155, which was downregulated in the presence of anti-miR-155. mTREM-1 induced expression of TNF (B), IL-6 (C), and IL-1β (D) mRNA; however, treatment with miR-155 antagomir resulted in abrogation of this induction. Wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice were treated with aerosolized LPS (10 mg/kg). Lungs from TREM-1 knockout mice showed a significant downregulation of miR-155-3p and -5p (E) after treatment with LPS. *P < 0.05; n = 4–5.

miR-155 is induced by TREM-1 in an NF-κB-dependent manner.

Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) is miR-155 target induced by TREM-1. Next, we wanted to determine the mechanism by which TREM-1 activation induces miR-155. MIR155HG (pri-miR-155) is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB, AP-1, and ETS-1. The proximal promoter region of MIR155HG has several NF-κB binding sites (9). We therefore questioned if induction of miR-155 by TREM-1 is regulated by NF-κB. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml), control IgG, LPS (100 ng/ml), or sterile PBS, respectively, and with or without the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11–7082 (1 μmol/; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were harvested 16 h following treatment, and expression of miR155-3p and -5p and MIR155HG (pri-mir-155) was determined by real-time RT-PCR. Treatment with mTREM-1 and LPS induced the expression of miR155-3p and -5p and MIR155HG, which was significantly reduced by treatment with NF-κB inhibitor Bay11-7082 (Fig. 4, A–C). These data suggest that induction of miR-155 by TREM-1 is at least partially mediated through NF-κB.

Fig. 4.

miR-155 is induced by TREM-1 in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) is a miR-155 target induced by TREM-1. RAW264.7 cells were treated with mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml) or control IgG or LPS (100 ng/ml) or PBS with or without the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11–7082(1 μmol/l). Expression of miR-155-5p (A), miR-155-3p (B), and Mir155hg (C) was determined by real-time PCR at 16 h posttreatment. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with miR-155-3p and miR-155-5p antagomir (100 nmol/l) and mirVana miRNA Inhibitor Negative Control (100 nmol/l), 48 h later, cultured in DMEM media with or without mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml) and LPS (100 ng/ml), respectively. D: SOCS-1 mRNA expression was determined at 16 h. Data represent the mean ± SD percentages cells from 3 independent experiments for both untreated cells (open bars) and cells treated with 1 μmol/l Bay 11–7082 (solid bars). *P < 0.05.

We then wanted to determine how miR-155 induces a proinflammatory response. By using bioinformatics approach and the miRDB database we found that SOCS-1 is a target of miR-155. Since SOCS-1 negatively regulates the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines, we hypothesized that miR-155 might mediate its effects through downregulation of SOCS-1. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with antagomir against miR-155-3p, miR-155-5p (100 nmol/l), and mirVana miRNA Inhibitor Negative Control (mock) (100 nmol/l) for 48 h. Cells were then treated with mTREM-1 (10 ng/ml) or isotype IgG, LPS (100 ng/ml), or sterile PBS for 16 h. Expression of SOCS-1 mRNA was determined by real-time RT-PCR. Control cells that were treated with mock antagomirs and mTREM-1 and LPS showed a significantly reduced expression of SOCS-1 mRNA. Cells that were treated with antagomir against miR-155 and mTREM-1 antibody or LPS showed increased expression of SOCS-1 (Fig. 4D). These data show that TREM-1-induced miR-155 mediates its effects through downregulation of SOCS-1 which regulates proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6.

TREM-1 knockdown confers a favorable immunometabolic adaptation in macrophages in response to LPS.

Our data show that blockade of TREM-1 attenuates the inflammatory response in macrophages and lungs of mice challenged with LPS. We have recently shown that activation of TREM-1 confers antiapoptotic attributes to inflammatory cells by inducing the expression of mitofusins (52). Acute inflammatory conditions are associated with alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption in cells depending on the stimulus and state of activation (21, 28, 46). To define the physiologic impact of TREM-1 silencing in acute inflammation, we asked if the anti-inflammatory effects of blocking TREM-1 altered the immunometabolic response of macrophages to LPS. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with siTREM-1 or control siRNA, following which mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation reactions and respiratory assays were assessed by measuring the OCR through the XF-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer. Compared with control cells, we found that TREM-1 silenced cells demonstrated reduced basal OCR (Fig. 5A), ATP turnover, maximal respiration (Fig. 5B), and proton leak level (Fig. 5C), suggesting that TREM-1 silencing alters the basal OCR and mitochondrial respiration. With a decrease in the oxygen consumption, cells shifted from a primary oxidative metabolic state towards glycolytic metabolism with increased ECAR (Fig. 5, D and E).

Fig. 5.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics in RAW264.7 cells showed lower oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in TREM-1 knockdown cells. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with siTREM-1 or control siRNA, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation reactions and respiratory assays were assessed by a Seahorse analyzer. Basal and spare respiratory OCR (A), ATP turnover and maximal respiration (B), proton leak (C), and ECAR (D) were measured in real time under basal conditions and in response to indicated mitochondrial inhibitors. R/A, rotenone/antimycin. E: basal OCR/ECAR ratio. *P < 0.05; n = 12.

Next, we performed experiments to determine the immunometabolic state of macrophages from TREM-1 knockout mice in response to LPS. BMDM from wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or sterile PBS for 4 h. Mitochondrial respiratory assays showed that wild-type cells treated with LPS showed an increased OCR (Fig. 6A), ATP turnover (Fig. 6B), and proton leak (Fig. 6C) compared with the PBS-treated cells. On the contrary, TREM-1 knockout cells showed a significant reduction in OCR, ATP turnover, and proton leak, suggesting that deletion of TREM-1 alters that mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and confers a favorable immunometabolic phenotype to the macrophages. Since we have shown that TREM-1 mediates its effects through miR-155, we aimed to investigate the effects of miR-155 on mitochondrial oxygen consumption and respiration. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with miR-155-3p mimic (100 nmol/l) and mirVana miRNA mimic Negative Control (100 nmol/l; Life Technologies) through a specific Lonza transfection reagent for 48 h. We confirmed that miR-155 expression increased in cells transfected with miR-155 mimic, compared with cells transfected with the control miRNA (Fig. 7A). OCR and respiration were measured in real time under basal conditions and in response to the indicated mitochondrial inhibitors. OCR (Fig. 7B), ATP production, and maximal respiration (Fig. 7C), and proton leak (Fig. 7D) were increased similar to that of LPS. Cells also showed a shift towards glycolytic metabolism with increased ECAR (Fig. 7E). Together these data indicate that the altered inflammatory response by LPS and miR-155 increases the mitochondrial oxygen consumption and that inhibiting TREM-1 physiologically confers a metabolic advantage to the cells by reducing the OCR.

Fig. 6.

TREM-1 knockout macrophages showed lower OCR and maximal respiration after treatment with LPS compared with wild-type macrophages. BMDM from wild-type and TREM-1 knockout mice were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h, and mitochondrial bioenergetics were determined using a Seahorse analyzer. OCR and basal respiration (A), ATP turnover and maximal respiration (B), and proton leak (C). *P < 0.05; n = 12.

Fig. 7.

miR-155-3p mimic increases mitochondrial OCR and ECAR. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with miR-155-3p mimic (100 nmol/l) and mirVana miRNA mimic Negative Control (100 nmol/l). A: miR-155-3p expression was measured in RAW264.7 cells transfected with miR-155-3p mimic and negative control. Mitochondrial bioenergetics were measured in transfected cells using a Seahorse analyzer. B: OCR in real time under basal conditions and in response to indicated mitochondrial inhibitors. C: ATP production and maximal respiration. D: proton leak. E: ECAR. F: basal OCR/ECAR ratio. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments and shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.0001.

TREM-1-blocking nanomedicine effectively attenuates LPS-induced lung injury.

Previous studies where TREM-1 blockade has been used therapeutically in models of sepsis and infection have employed fusion proteins (soluble or extracellular component of TREM-1). These peptides are limited by their short half life and therefore may not be practical for therapeutic purposes (3, 15, 53). In recent years nanotechnology for drug delivery has been increasingly used and is a rapidly expanding field (24, 27, 40, 42). To effectively block the expression of TREM-1, we have developed a LP17 peptide nanomedicine, LP17-SSM. LP17 is the soluble TREM-1 or extracellular component that binds and inhibits signaling through TREM-1. Control SSMs were prepared by using scrambled peptide.

For the TREM-1 blocking peptide LP17, circular dichroism confirmed that there was a significant increase in α-helicity in the presence of SSM compared with the free peptides in normal saline. This indicated the presence of peptide-micelle interaction where the peptides changed from a random conformation in saline to a more ordered helical structure when associated with SSM (data not shown).

To determine in vivo anti-inflammatory efficacy and dose-response effect of LP17-SSM, three peptide doses were tested: 1, 3, and 10 nmol (per mouse). These peptide doses were based on our earlier animal studies with GLP-1-SSM (27), and pilot acute lung injury (ALI) animal studies at 3 and 10 nmol of LP17/TREM-1(per mouse), which showed promising trend of anti-inflammatory efficacy (data not shown). Ten nanomoles of LP17-SSM/mouse were subsequently tested to determine potential therapeutic ceiling effect of LP17-SSM. Mice were given one dose of LP17 nanomedicine, nanoscrambled peptide, PBS, or LP17 subcutaneously in a single dose before LPS challenge. All subcutaneous injections were given in a 100-μl injection volume. The ALI animal model used was based on previous publications (27, 41). Mice were challenged with aerosolized LPS by nebulization (8 mg LPS dissolved in PBS at the concentration of 1 mg/ml) administered via a DeVilbiss disposable nebulizer (at the continuous air flow rate of 10 ft3/h) over 1 h to induce ALI. The animals were killed 12 h after LPS nebulization.

First, we detected the fold change in TREM-1 gene induced by LP17 and LP17 nanomedicine in the lungs of mice. LP17 inhibited the expression of TREM-1; however, there was a significantly lower expression of TREM-1 gene in response to LP17 nanomedicine (n = 5–8; P < 0.003; Fig. 8A). BAL cell counts (Fig. 8B), MPO measurements from lung homogenates (Fig. 8C), lung wet-to-dry ratio (Fig. 8D), and BAL proteins (Fig. 8E) were significantly lower in mice that received LP17 nanomedicine, in comparison with mice that were treated with LP17. As shown in Fig. 8A, mice that were treated with scrambled LP17 or nanomedicine of scrambled peptide did not show any attenuation of TREM-1 mRNA expression. Levels of TNF-α and IL-1α protein measured by ELISA were also significantly decreased in mice that were treated with LP17 nanomedicine compared with LP17 (Fig. 8, F and G). Control nanomedicine and peptide did not result in attenuation of TREM-1 expression or inflammatory response. These data suggest that nanomiceller preparation of TREM-1 inhibitory peptide is more efficacious than naked peptide and can effectively mitigate lung inflammation in LPS-induced lung injury.

Fig. 8.

LP17 nanomedicine [LP17- sterically stabilized phospholipid nanomicelles (SSM) SSM] attenuate LPS-induced neutrophilic lung inflammation. Wild-type mice were treated with LP17 or scrambled LP17, LP17 SSM, or scrambled SSM via subcutaneous route before treatment with aerosolized LPS (1 mg/ml). Expression of TREM-1 in the lung was significantly reduced by LP17 SSM (A), and BAL total and neutrophil (B), MPO assays from lung homogenates (C), lung wet-to-dry ratio (D), BAL proteins (E), TNF-α (F), and IL-1β (G) levels were significantly lower in mice that were treated with LP17 SSM compared with naked peptide (LP17). *P < 0.05; n = 6–7.

DISCUSSION

In this study we show that TREM-1 expression is induced in lungs of mice with LPS -induced acute lung injury. Furthermore, we show that TREM-1 knockout mice have improved survival with attenuated inflammatory response in a lethal model of lung injury. Mechanistically, we show that TREM-1 mediates its proinflammatory effects through the induction of miR-155, which regulates expression of SOCS-1. Furthermore, our data show that physiologically TREM-1 deletion improves mitochondrial bioenergetics favoring an adaptation mode that could enhance resolution. By employing novel nanomicellar preparations, we show that TREM-1 nanomicelles are more efficacious at attenuating lung injury than the naked peptides. These studies will have important implications for the future management of patients with ARDS.

TREM proteins are a family of immunoglobulin cell surface receptors expressed on myeloid cells and have been shown to amplify TLR-induced responses (2, 3). The precise ligand for TREM-1 is not well characterized; however, we and others have shown that bacteria, viruses (3, 30, 35), and endogenous mediators, such as PGE2 (50) and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), induce expression of TREM-1 (47, 54). A recent study by Read et al. (37) identified complexes between peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 (PGLYRP1) and bacterially derived peptidoglycan as potent ligands capable of binding to TREM-1 and inducing known TREM-1 functions. We have also shown that PGD2 and PGJ2 inhibit the expression of TREM-1 (45). Gene regulation of TREM-1 has been charachterized, and we have shown that binding of p65 to its cognate site in TREM-1 promoter leads to activation of TREM-1, whereas PU.1 binding causes transcriptional repression (55). Furthermore, we have shown that MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling determines the expression of TREM-1 in response to specific TLR ligand and that presence of TLRs is necessary for the expression of TREM-1 in response to a specific TLR ligands (35, 56). These observations suggest that synergy between TLR and TREM-1 pathways ensures the highest level of cell stimulation leading to a robust inflammatory response (53). More recently, we have shown that TREM-1 activation inhibits apoptosis of macrophages through Bcl-2-Egr2 signaling thus prolonging the survival of inflammatory macrophages, which is a potential mechanism by which TREM-1 activation can perpetuate inflammation (52). These data suggest that TREM-1 activation plays a critical role in amplifying the inflammatory response by a variety of mechanisms.

Since TREM-1 signaling amplifies inflammatory response, we hypothesized that blockade of TREM-1 will attenuate lung inflammation. Indeed our data support this hypothesis in LPS-induced lung inflammation. We used a model of neutrophilic lung inflammation induced by aerosolized LPS or intraperitoneal LPS and showed that TREM-1 knockout mice have an improved survival and attenuated inflammatory response. Previous studies have shown that TREM-1 blockade improves survival in sepsis (2, 3). In humans with sepsis, it has been shown that the levels of soluble component shed from the cell surface (sTREM-1) can be a marker of severity and prognosis (12, 13, 17). Recent studies suggest that TREM-1 activation also occurs in other inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis gout, and rheumatoid arthritis (22, 26, 32, 36, 49). A recent study by Boufenzer et al. (4) showed that following mycardial infarction TREM-1 expression is upregulated in ischemic myocardium in mice and humans. Deletion of the TREM-1 gene or pharmacologic inhibition dampened myocardial inflammation with attenuation of neutrophiic recruitment and MCP-1 production, thus reducing classical monocytes mobilization to the heart. During both permanent and transient myocardial ischemia, TREM-1 blockade ameliorated cardiac function (4). Our data are in agreement with this study and show that TREM-1 expression is increased in lungs of mice that are treated with LPS and that inhibition of TREM-1 attenuates neutrophilic lung inflammation. The in vivo phenotype of TREM-1 knockout mice can be attributed to deletion of TREM-1 gene in both macrophages and neutrophils. We have not employed cell-specific knockout approaches, and therefore our studies are limited by the fact that we have not been able to discern the role of TREM-1 in specific cell types in vivo. Cell-specific knockout studies are currently ongoing but are beyond the scope of this article. Our data also show that TREM-1 knockout confers improved mitochondrial bioenergetis, which may be a reflection of reduced inflammation; however, the precise mechanisms by which TREM-1 contributes to immunometabolic changes will need further investigations.

TREM-1 blockade in models of infection sepsis has used peptides and fusion proteins, which are limited by their short half life, and therefore, the practical utility of this approach is limited (3, 14–16, 18). In recent years, nanotechnology has become a rapidly expanding field. Nanoscale drug delivery systems are able to improve the pharmacokinetics and increase the biodistribution of therapeutic agents to target organs, thereby resulting in improved efficacy and reduced drug toxicity (24, 42). Nanocarriers are particularly designed to target inflammation and cancer that have permeable vasculature, and they improve solubility of hydrophobic compounds in aqueous media to render them suitable for parenteral administration (42). In particular the delivery systems have been shown to increase the stability of a wide variety of therapeutic agents such as hydrophobic molecules, peptides, and oligonucleotides (25, 40). Recently, we have used this approach to develop peptide nanomedicines of VIP and GLP-1. Results showed that GLP-1 nanomedicine was effective at attenuating lung injury (27). Using a similar approach in this study we have developed nanomedicine of LP17 to block the expression of TREM-1. We compared the efficacy of free LP17 (TREM-1 blocking peptide) to a LP17-SSM and showed that a single subcutaneous dose of this nanomedicine preparation is effective at attenuating neutrophlic lung inflammation. Future studies using this novel nanomedicine in patients with ARDS will be important to delineate its role in human diseases.

Similar to our data, in an acute pneumonia model caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, inhibiting TREM-1 signaling attenuated lung inflammation and injury and reduced lethality (14). However, recent studies that have employed TREM-1 knockout mice suggest a protective role for TREM-1 in immunity during P. aeruginosa (23), Klebsiella (19), and S. pneumonia (20). These studies show that TREM-1/3 deficiency led to increased lethality, accompanied by enhanced growth of bacteria. Together these studies suggest that TREM-1 plays a critical role in innate immune response to invading bacteria, and therefore, blocking TREM-1 should be approached with caution in models of acute infection. Given the complex nature of innate immune response, it is possible that the timing of blockade of TREM-1 may be important. In a setting of infection, activation of TREM-1 during earlier time points may be necessary for the host to mount an adequate response; however, at later times in disease, such as in ARDS, blockade of TREM-1 may limit inflammation and enhance resolution. Ongoing studies will clarify the role of TREM-1 blockade in innate immune response by pharmacologic inhibition. However, in models of dysregulated inflammation, most data are in agreement and suggest that blockade of TREM-1 may be a potential therapeutic approach.

Our studies also show that TREM-1 silencing could improve mitochondrial bioenergetics, which may confer an immunometabolic advantage to mitochondrial respiration and spare the respiratory capacity of inflammatory cells. In BMDM, Huang et al. (21) showed that macrophages that are activated with IL-4 (M2 phenotype) show an increased OCR and respiratory spare capacity compared with unactivated macrophages; however, cells that were treated with IFN-γ and LPS showed no evidence of increased OCR. On the other hand, Liu et al. (28) showed that macrophages that are treated with LPS alone show a biphasic response with a shift in mitochondrial bioenergetics with an increase in OCR in the adaptation phase. They also showed that monocytes from septic patients show an increase in OCR. Our data are in agreement with these results and show that altered inflammatory responses by LPS and miR-155 increase the mitochondrial oxygen consumption and that inhibiting TREM-1 physiologically confers a metabolic advantage to the cells by reducing the OCR.

As regulators at the posttranscriptional level, miRNAs are noncoding 19–22 nucleotide RNA molecules that regulate the expression of multiple genes (43). To date there is no information about TREM-1-mediated changes in miRNAs in the context of immune response. Since TREM-1 signaling alters multitude of key effector proteins, we investigated the effects of TREM-1 on miRNA expression of macrophages in response to LPS. Macrophages from TREM-1 knockout mice showed a significant downregulation of miR-155-3p, miR-155-5p, miR-32, miR-466l, and miR-665 in response to LPS, which were upregulated in the wild-type macrophages. Predicted targets of miRNAs confirmed that the differential expression of these miRNAs was translated in the differences in genes of key signaling molecules that define the immune response.

Since the expression of miR-155 was significantly downregulated in TREM-1 knockout macrophages, and miR-155 is known to propogate inflammatory response, we investigated if the effects of TREM-1 signaling are mediated through miR-155. By employing miR-155 antagomir, in vitro data in macrophages confirmed that the TREM-1-induced effects on TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are mediated by miR-155. Previous studies have indicated that miR-155 may enhance inflammatory response by stimulating the release of inflammatory mediators by targeting several negative feedback molecules, including SOCS-1 and SH2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase (SHIP)-1 (1, 8, 29). Therefore, we investigated the effects of TREM-1 activation on SOCS-1. Our data show that mTREM-1 reduced the expression of SOCS-1 and that antagomir against miR-155 increased the expression of SOCS-1 in cells treated with mTREM-1 or LPS. Together these data suggest that TREM-1 induces proinflammatory effects through miR-155 and its target SOCS-1. Our studies are limited by the fact that we have not investigated the role of other miRNAs that were altered by TREM-1 activation. The contribution of these miRNAs is ongoing in our laboratory, and future studies will establish their role in TREM-1 signaling.

In conclusion, our data show that deletion of TREM-1 gene improves survival in a LPS-induced neutrophilic lung inflammation. Macrophages from TREM-1 knockout mice showed significant alterations in the expression of key miRNAs that contribute to inflammation. In particular, expression of miR-155-3p and -5p was significantly downregulated in TREM-1 knockout macrophages, and the proinflammatory effects of TREM-1 activation in macrophages are mediated through miR-155 and its target SOCS-1. Our data also show that TREM-1 silencing could improve mitochondrial bioenergetics, which may confer an immunometabolic advantage to mitochondrial respiration and spare the respiratory capacity of inflammatory cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate a novel nanomicellar approach to block TREM-1 effects and show that the LP17 nanomedicine is more efficacious than free peptide at attenuating lung inflammation. These data for the first time show that TREM-1 mediates proinflammatory effects by inducing miR-155 suggesting a novel mechanism by which TREM-1 signaling contributes to the inflammatory, response. Our data also suggest that TREM-1 is a therapeutic target for treatment of ARDS.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Merit Review funding (to R. Sadikot and I. Rubinstein), National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG-024026 (to I. Rubinstein), and Parenteral Drug Association (to H. Onyuksel).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.Y., M.S., D.P., C.B., and S.L. performed experiments; Z.Y., D.P., and S.L. analyzed data; Z.Y. prepared figures; Z.Y. and R.T.S. drafted manuscript; M.J., H.O., I.R., and R.T.S. edited and revised manuscript; H.O., I.R., and R.T.S. interpreted results of experiments; M.C. and R.T.S. conception and design of research; R.T.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Billeter AT, Hellmann J, Roberts H, Druen D, Gardner SA, Sarojini H, Galandiuk S, Chien S, Bhatnagar A, Spite M, Polk HC Jr. MicroRNA-155 potentiates the inflammatory response in hypothermia by suppressing IL-10 production. FASEB J 28: 5322–5336, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol 164: 4991–4995, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA, Colonna M. TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature 410: 1103–1107, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boufenzer A, Lemarie J, Simon T, Derive M, Bouazza Y, Tran NN, Maskali F, Groubatch F, Bonnin P, Bastien C, Bruneval P, Marie PY, Cohen R, Danchin N, Silvestre JS, Ait-Oufella H, Gibot S. TREM-1 mediates inflammatory injury and cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction. Circ Res 116: 1772–1182, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brower RG, Ware LB, Berthiaume Y, Matthay MA. Treatment of ARDS. Chest 120: 1347–1367, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Liu W, Sun T, Huang Y, Wang Y, Deb DK, Yoon D, Kong J, Thadhani R, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D promotes negative feedback regulation of TLR signaling via targeting microRNA-155-SOCS1 in macrophages. J Immunol 190: 3687–3695, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colonna M, Facchetti F. TREM-1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells): a new player in acute inflammatory responses. J Infect Dis 187, Suppl 2: S397–401, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du F, Yu F, Wang Y, Hui Y, Carnevale K, Fu M, Lu H, Fan D. MicroRNA-155 deficiency results in decreased macrophage inflammation and attenuated atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 759–767, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elton TS, Selemon H, Elton SM, Parinandi NL. Regulation of the MIR155 host gene in physiological and pathological processes. Gene 532: 1–12, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford JW, McVicar DW. TREM and TREM-like receptors in inflammation and disease. Curr Opin Immunol 21: 38–46, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank AJ, Thompson BT. Pharmacological treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Immunol 16: 62–68, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibot S. Clinical review: role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 during sepsis. Crit Care 9: 485–489, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibot S. The therapeutic potential of TREM-1 modulation in the treatment of sepsis and beyond. Curr Opin Invest Drugs 7: 438–442, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibot S, Alauzet C, Massin F, Sennoune N, Faure GC, Bene MC, Lozniewski A, Bollaert PE, Levy B. Modulation of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 pathway during pneumonia in rats. J Infect Dis 194: 975–983, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibot S, Buonsanti C, Massin F, Romano M, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Benigni F, Faure GC, Bene MC, Panina-Bordignon P, Passini N, Levy B. Modulation of the triggering receptor expressed on the myeloid cell type 1 pathway in murine septic shock. Infect Immun 74: 2823–2830, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Bene MC, Bollaert PE, Lozniewski A, Mory F, Levy B, Faure GC. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. J Exp Med 200: 1419–1426, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibot S, Le Renard PE, Bollaert PE, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Bene MC, Faure GC, Levy B. Surface triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 expression patterns in septic shock. Intens Care Med 31: 594–597, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibot S, Massin F, Marcou M, Taylor V, Stidwill R, Wilson P, Singer M, Bellingan G. TREM-1 promotes survival during septic shock in mice. Eur J Immunol 37: 456–466, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hommes TJ, Dessing MC, van't Veer C, Florquin S, Colonna M, de Vos AF, Poll TV. TREM-1/3 contribute to protective immunity in Klebsiella derived pneumosepsis whereas TREM-2 does not. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53: 647–655, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hommes TJ, Hoogendijk AJ, Dessing MC, Van't Veer C, Florquin S, Colonna M, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) improves host defence in pneumococcal pneumonia. J Pathol 233: 357–367, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O'Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O'Neill CM, Yan C, Du H, Abumrad NA, Urban JF Jr, Artyomov MN, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol 15: 846–855, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamei K, Yasuda T, Ueda T, Qiang F, Takeyama Y, Shiozaki H. Role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 17: 305–312, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klesney-Tait J, Keck K, Li X, Gilfillan S, Otero K, Baruah S, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM, Knudson CJ, Moninger TO, Moreland J, Zabner J, Colonna M. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils into the lung requires TREM-1. J Clin Invest 123: 138–149, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo OM, Rubinstein I, Onyuksel H. Role of nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery and imaging: a concise review. Nanomedicine 1: 193–212, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnadas A, Rubinstein I, Onyuksel H. Sterically stabilized phospholipid mixed micelles: in vitro evaluation as a novel carrier for water-insoluble drugs. Pharm Res 20: 297–302, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuai J, Gregory B, Hill A, Pittman DD, Feldman JL, Brown T, Carito B, O'Toole M, Ramsey R, Adolfsson O, Shields KM, Dower K, Hall JP, Kurdi Y, Beech JT, Nanchahal J, Feldmann M, Foxwell BM, Brennan FM, Winkler DG, Lin LL. TREM-1 expression is increased in the synovium of rheumatoid arthritis patients and induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48: 1352–1358, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim SB, Rubinstein I, Sadikot RT, Artwohl JE, Onyuksel H. A novel peptide nanomedicine against acute lung injury: GLP-1 in phospholipid micelles. Pharm Res 28: 662–672, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu TF, Vachharajani V, Millet P, Bharadwaj MS, Molina AJ, McCall CE. Sequential actions of SIRT1-RELB-SIRT3 coordinate nuclear-mitochondrial communication during immunometabolic adaptation to acute inflammation and sepsis. J Biol Chem 290: 396–408, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mashima R. Physiological roles of miR-155. Immunology 145: 323–333, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohamadzadeh M, Coberley SS, Olinger GG, Kalina WV, Ruthel G, Fuller CL, Swenson DL, Pratt WD, Kuhns DB, Schmaljohn AL. Activation of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 on human neutrophils by marburg and ebola viruses. J Virol 80: 7235–7244, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molloy EJ. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) family and the application of its antagonists. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov 4: 51–56, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami Y, Akahoshi T, Aoki N, Toyomoto M, Miyasaka N, Kohsaka H. Intervention of an inflammation amplifier, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1, for treatment of autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 1615–1623, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathan C, Ding A. TREM-1: a new regulator of innate immunity in sepsis syndrome. Nat Med 7: 530–532, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 1604–1609, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ornatowska M, Azim AC, Wang X, Christman JW, Xiao L, Joo M, Sadikot RT. Functional genomics of silencing TREM-1 on TLR4 signaling in macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1377–L1384, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JJ, Cheon JH, Kim BY, Kim DH, Kim ES, Kim TI, Lee KR, Kim WH. Correlation of serum-soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 with clinical disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 54: 1525–1531, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Read CB, Kuijper JL, Hjorth SA, Heipel MD, Tang X, Fleetwood AJ, Dantzler JL, Grell SN, Kastrup J, Wang C, Brandt CS, Hansen AJ, Wagtmann NR, Xu W, Stennicke VW. Cutting edge: identification of neutrophil PGLYRP1 as a ligand for TREM-1. J Immunol 194: 1417–1421, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 353: 1685–1693, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubenfeld GD, Herridge MS. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute lung injury. Chest 131: 554–562, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadikot RT. Peptide nanomedicines for treatment of acute lung injury. Methods Enzymol 508: 315–324, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadikot RT, Jansen ED, Blackwell TR, Zoia O, Yull F, Christman JW, Blackwell TS. High-dose dexamethasone accentuates nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endotoxin-treated mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 873–878, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadikot RT, Rubinstein I. Long-acting, multi-targeted nanomedicine: addressing unmet medical need in acute lung injury. J Biomed Nanotechnol 5: 614–619, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwerk J, Savan R. Translating the untranslated region. J Immunol 195: 2963–2971, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharif O, Knapp S. From expression to signaling: roles of TREM-1 and TREM-2 in innate immunity and bacterial infection. Immunobiology 213: 701–713, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Syed MA, Joo M, Abbas Z, Rodger D, Christman JW, Mehta D, Sadikot RT. Expression of TREM-1 is inhibited by PGD2 and PGJ2 in macrophages. Exp Cell Res 316: 3140–3149, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH, Zheng L, Gardet A, Tong Z, Jany SS, Corr SC, Haneklaus M, Caffrey BE, Pierce K, Walmsley S, Beasley FC, Cummins E, Nizet V, Whyte M, Taylor CT, Lin H, Masters SL, Gottlieb E, Kelly VP, Clish C, Auron PE, Xavier RJ, O'Neill LA. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature 496: 238–242, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tessarz AS, Cerwenka A. The TREM-1/DAP12 pathway. Immunol Lett 116: 111–116, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, Fabbri M, Alder H, Liu CG, Calin GA, Croce CM. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol 179: 5082–5089, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasuda T, Takeyama Y, Ueda T, Shinzeki M, Sawa H, Takahiro N, Kamei K, Ku Y, Kuroda Y, Ohyanagi H. Increased levels of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in patients with acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Med 36: 2048–2053, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan Z, Mehta HJ, Mohammed K, Nasreen N, Roman R, Brantly M, Sadikot RT. TREM-1 is induced in tumor associated macrophages by cyclo-oxygenase pathway in human non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 9: e94241, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan Z, Panchal D, Syed MA, Mehta H, Joo M, Hadid W, Sadikot RT. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 signaling by Stomatococcus mucilaginosus highlights the pathogenic potential of an oral commensal. J Immunol 191: 3810–3817, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan Z, Syed MA, Panchal D, Joo M, Colonna M, Brantly M, Sadikot RT. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1)-mediated Bcl-2 induction prolongs macrophage survival. J Biol Chem 289: 15118–15129, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Z, Syed MA, Panchal D, Rogers D, Joo M, Sadikot RT. Curcumin mediated epigenetic modulation inhibits TREM-1 expression in response to lipopolysaccharide. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 2032–2043, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanzinger K, Schellack C, Nausch N, Cerwenka A. Regulation of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 expression on mouse inflammatory monocytes. Immunology 128: 185–195, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng H, Ornatowska M, Joo MS, Sadikot RT. TREM-1 expression in macrophages is regulated at transcriptional level by NF-kappaB and PU.1. Eur J Immunol 37: 2300–2308, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng H, Heiderscheidt CA, Joo M, Gao X, Knezevic N, Mehta D, Sadikot RT. MYD88-dependent and -independent activation of TREM-1 via specific TLR ligands. Eur J Immunol 40: 162–171, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]