Abstract

RNA interference has had major advances as a developing tool for pest management. In laboratory experiments, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is often administered to the insect by genetic modification of the crop, or synthesized in vitro and topically applied to the crop. Here, we engineered genetically modified yeast that express dsRNA targeting y-Tubulin in Drosophila suzukii. Our design takes advantage of the symbiotic interactions between Drosophila, yeast, and fruit crops. Yeast is naturally found growing on the surface of fruit crops, constitutes a major component of the Drosophila microbiome, and is highly attractive to Drosophila. Thus, this naturally attractive yeast biopesticide can deliver dsRNA to an insect pest without the need for genetic crop modification. We demonstrate that this biopesticide decreases larval survivorship, and reduces locomotor activity and reproductive fitness in adults, which are indicative of general health decline. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that yeast can be used to deliver dsRNA to an insect pest.

In recent years, RNA interference (RNAi) has shown great potential to become a powerful tool in pest management. RNAi is effective in many economically important insects, including honey bee, aphid, termite, mosquito, western corn rootworm, and Colorado potato beetle1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. With genomic data becoming increasingly available for non-model insects, sequence-based pest management strategies are becoming more practical. Inducing mortality through RNAi has several advantages over conventional chemical pesticides. As a consequence of its sequence-dependent mode of action, RNAi can be tailored to target only pest species and spare beneficial insects9,10. This is accomplished by choosing to target unique mRNA sequences within the pest species. Likewise, RNAi pesticides can be designed to target a broad range of insects by choosing sequences that are more conserved between species. Another advantage of RNAi pesticides is that the “active ingredient” is RNA, which is organic, biodegradable, and can be inexpensively produced within microorganisms.

RNAi is a cellular mechanism that likely evolved to protect eukaryotes from RNA viruses11. To activate the RNAi pathway, double stranded RNA (dsRNA) can be fed to insects and absorbed into the cells that line the midgut. Exogenous dsRNA is usually processed into 20–30 nucleotide duplexes by the ribonuclease III enzyme DICER12,13,14. These nucleotide duplexes are assembled onto the catalytic component ARGONAUTE and a single guide strand is incorporated into the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC)13. The guide strand binds to complementary mRNAs, and the RISC complex mediates degradation or translational suppression of the endogenous transcript. The RISC complex will cleave the mRNA when base pair matching is highly complementary, or alternatively, the complex can bind the mRNA and suppress translation when there are mismatched base pairs. Degradation or suppression of transcripts that code for critical genes in the insect results in decreased amounts of critical gene products and increased mortality14,15.

Some species, such as C. elegans, possess a SID-1 RNA channel transporter that facilitates uptake of dsRNA into cells16. Dipterans do not posses a SID1 ortholog, but are able to absorb dsRNA through other mechanisms, such as receptor mediated endocytosis17. Studies have shown dsRNA can enter Drosophila melanogaster cells through injection into whole animals18 or through addition to the growth medium of cultured cells19. Whyard et al.20 demonstrated that Drosophilids are able to uptake dsRNA from oral ingestion of dsRNA solution containing a lipid encapsulating reagent, resulting in tissue-specific gene suppression and mortality. Importantly, this study supports the idea that a Drosophilid pest could be controlled through oral delivery of dsRNA.

Delivery of intact dsRNA into insect cells remains a challenge, although many delivery methods have been developed14. Crops can be genetically engineered to express dsRNA targeting insect pests6,21. The use of modified plants has proven remarkably effective in managing coleopteran pests such as western corn rootworm6. Another delivery method is to synthesize the dsRNA in vitro, and then apply to foliage by spraying22, or to roots by soaking23, resulting in a transient presence of dsRNA within the plant tissue. Nanoparticles composed of chitosan and dsRNA have been used to deliver dsRNA to larval mosquitos through oral ingestion24. Zhu et al.26 demonstrated that bacteria expressing dsRNA can be fed to insects to induce RNAi25,26, and genetically modified bacteria can even colonize the gut and deliver dsRNA from within the host27.

The aim of this study is to demonstrate that genetically modified yeast can be used to produce and deliver dsRNA to Drosophila, resulting in altered gene expression and decreased fitness in the fly. We chose to use yeast as a delivery vehicle for dsRNA because of the symbiosis between yeast, Drosophila, and fruits. Yeast is an important endosymbiont and a major component of the microbiome in Drosophila28. Yeasts are naturally found growing on the surface of intact and rotting fruits and produce volatiles that are highly attractive to Drosophilids29,30. Palanca et al. quantified the attractive properties of wild yeast isolates and found fruit-associated isolates were more attractive than those not associated with fruit, regardless of taxonomic positioning31. Additionally, they found that Saccharomyces cerevisiae was the most attractive to Drosophila melanogaster. We therefore selected to modify S. cerevisiae for this study. S. cerevisiae lacks a functional RNAi mechanism32, which might make it a suitable dsRNA delivery vehicle if the absence of RNAi machinery promotes stability of dsRNA. Due to its frequent use as a model organism, S. cerevisiae has the added advantage of easy genetic manipulation. Drosophila acquire yeast from the environment and can transmit yeast horizontally to mates33. Drosophila-associated yeast spores can be passed intact through the gut and deposited onto food sources34, where they can be ingested by larvae or adults. Thus, yeast is a chemoattractive, transmittable symbiont of Drosophila and fruit crops. We postulate these characteristics make yeast an ideal and novel candidate to serve as a living biopesticide.

Drosophila suzukii, commonly known as Spotted Wing Drosophila, is an invasive pest of a variety of soft skinned fruits35. Native to South East Asia, this pest was first identified in California in 2008. Since then, infestations have spread across the United States, Canada, and Europe36, resulting in an estimated 718 million dollars in crop losses annually37,38. We chose to target D. suzukii in this study because it is a serious economic pest and is sufficiently homologous to the model insect D. melanogaster to facilitate target gene selection. Our laboratory has recently sequenced the D. suzukii genome, which further aids in the design of dsRNAs39. Additionally, yeast-baited traps have been demonstrated to effectively lure D. suzukii in an agricultural setting40, and evidence suggests that D. suzukii feed on yeasts in the field41.

Results

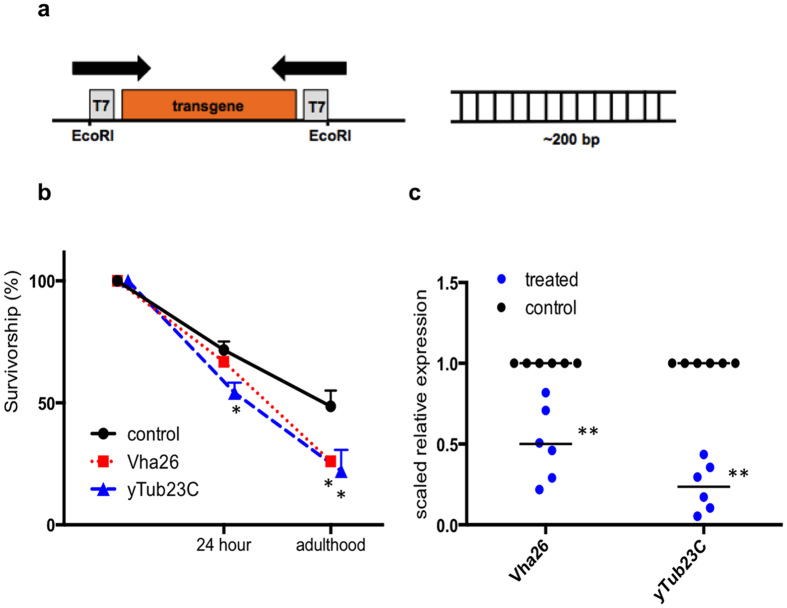

Treatment of larvae with in vitro transcribed dsRNA reduces expression of target genes and decreases survival to adulthood

Previous studies have demonstrated dsRNA can be synthesized and fed to insects in solution or artificial diet, resulting in gene knockdown and mortality1,20,42,43,44. This method is often used to select targets for in vivo testing. Critical genes tubulin and vacuolar ATPase are commonly used target genes and have effectively induced mortality in Coleopterans and Dipterans6,20. First, we examined whether dsRNA targeting y-tubulin 23C (yTub23C) and vacuolar H+ ATPase 26 kD subunit (Vha26) could be used to induce mortality in D. suzukii larvae. dsRNA was transcribed in vitro using a plasmid containing approximately 200 bp D. suzukii target gene sequence flanked with convergent T7 promoters (Fig. 1a). We found that a one-hour soaking treatment with in vitro transcribed dsRNA significantly reduced survival to adulthood by 54% and 46% respectively compared to the control (Fig. 1b). The control treatment had a 48% survival rate to adulthood. Next, we examined if the increased mortality was due to changes in target gene expression level. RNA was extracted from whole larval bodies 24 hours after the one-hour soaking treatment. Target transcripts yTub23C and Vha26 were significantly reduced relative to the control by 76% and 50% respectively in treated samples (Fig. 1c). These results suggest dsRNA in the soaking solution is absorbed and able to trigger an RNAi response in the larvae, resulting in mortality.

Figure 1. D. suzukii larvae treated with in vitro transcribed dsRNA have increased mortality and decreased target gene expression.

(a) Map of vector for in vitro transcription of dsRNA using convergent T7 promoters flanking ~200 bp of D. suzukii target gene sequence (yTub23C fragment =183 bp, Vha26 fragment =233 bp). Black arrows indicate direction of transcription. (b) Survivorship of 2nd instar larvae following soaking treatment with dsRNA solution. The control treatment consisted of Drosophila medium and lipid encapsulating reagent. Mortality was assessed 24 hours after treatment and at the time of eclosion. A total of 160 larvae were tested in each treatment, and data represent mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments. (c) Suppression of target genes yTub23C and Vha26 in whole larvae 24 hours after treatment with dsRNA solution. Ten larvae were homogenized to obtain one RNA sample. Expression was quantified with RT-qPCR and normalized against housekeeping gene Cbp20. Each data point represents a biological replicate, and horizontal lines indicate the mean. (b,c) Asterisks represent significance as determined by two-tailed t-test (*indicates p < 0.05, and **indicates p < 0.01).

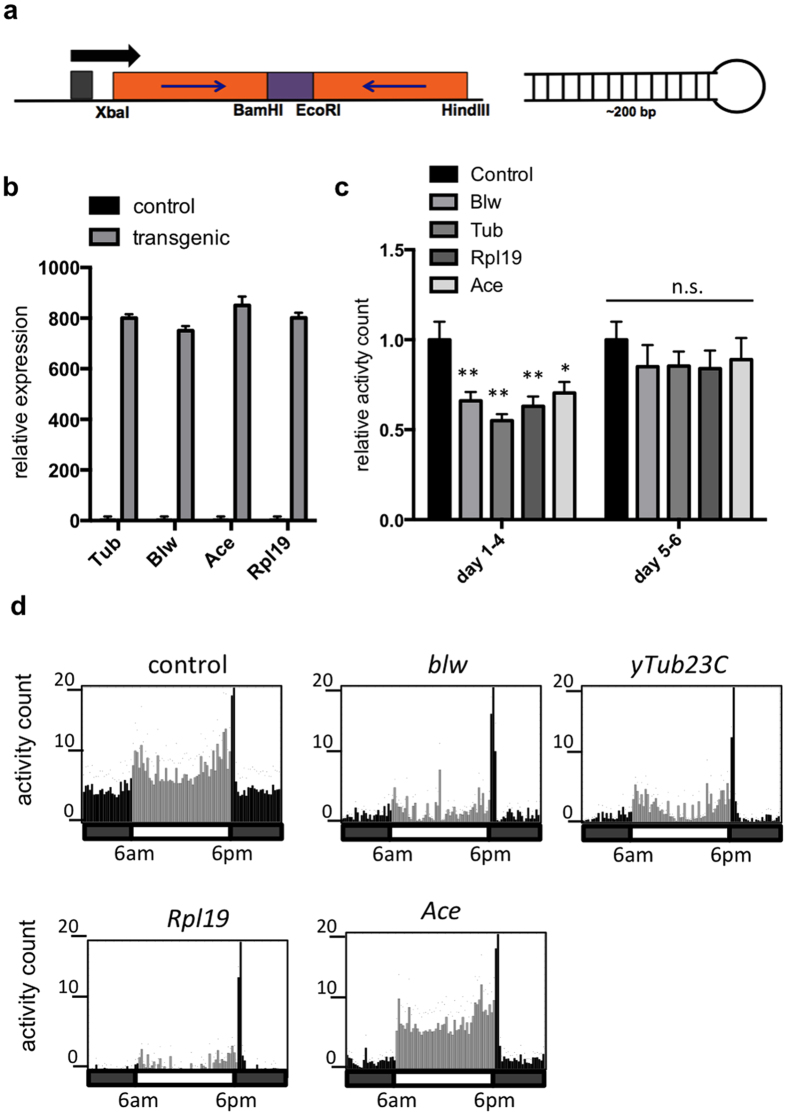

dsRNA targeting critical D. suzukii genes is expressed in modified Saccharomyces cerevisiae

DNA plasmids were constructed to constitutively express dsRNA hairpins targeting D. suzukii critical genes y-tubulin 23C (yTub23C) (183 bp), bellwether (blw) (230 bp), Ribosomal protein L19 (RpL19) (215 bp), and acetylcholine esterase (Ace) (221 bp). The rationale for selection of these target genes is stated in the methods section. Approximately 200 bp D. suzukii target gene sequence was inserted into a DNA plasmid to form inverted repeats joined by 74 bp of intron sequence from the white gene from D. melanogaster (Fig. 2a). This plasmid is self-replicating and does not integrate into the host yeast genome, so the host genome remains unchanged. Plasmids were transformed into S. cerevisiae strain INVSc1 using heat shock, and expression of dsRNA was verified using RT-qPCR (Fig. 2b). Empty P406TEF1 plasmid was transformed into S. cerevisiae strain INVSc1 to use as a control strain. As a control for dsRNA treatments, some studies use dsRNA targeting a gene from another species, such as GFP. We chose to use a yeast that contains empty plasmid and expresses no dsRNA as the control strain to avoid possible off target effects, such as suppression of critical genes that may have regions of sufficient homology to the control sequence to bring about an RNAi response45.

Figure 2. D. suzukii adults fed on yeast expressing dsRNA have decreased locomotor activity levels.

(a) Map of transformation vector for expression of hairpin dsRNA in S. cerevisiae. ~200 bp of D. suzukii target gene sequence was inserted into p406TEF1 to form inverted repeats linked by 74 bp of intron sequence from the white gene. Black arrow indicates direction of transcription. (b) Expression of dsRNA in S. cerevisiae. Expression was quantified with RT-qPCR and was normalized against housekeeping gene actin. Data represent mean and s.e.m. of three technical replicates. (c) Locomotor activity levels in D. suzukii following a three-day treatment with yeast expressing dsRNA targeting D. suzukii blw, yTub23C, Ace, and RpL19. Male adult flies were fed ad libitum with a choice between artificial diet and live yeast for three days. Activity was recorded for 6 days after the feeding period using the DAMS. The first through the fourth days of recording were averaged together, and days 5 and 6 were averaged. Data represent mean and s.e.m. of 3 independent experiments, and a total of 96 flies were tested per treatment. Each experiment was normalized to the average of the control treatment. One-way ANOVA was performed (p = 0.0009) and significance relative to the control was determined by post hoc Dunnett corrected t-test (*indicates p < 0.05 and **indicates p < 0.01). (d) Activity levels plotted over the second day of recording following three days of feeding treatment. Each bar represents average activity counts in 15-minute increments. Black bars indicate lights off and grey bars represent lights on. Presence or absence of light as well as the timing of light transition are also indicated in the horizontal bar underneath each activity graph; light turns on at 6am and turns off at 6pm each day of recording. Each activity graph represents an average of 32 flies in one experiment. Representative activity graphs are shown here.

D. suzukii adults fed on yeast expressing dsRNA have decreased locomotor activity levels

Initially, D. suzukii were continuously fed ad libitum for ten days with a choice between standard Drosophila artificial diet and live transformed yeast growing on solid agar. This feeding treatment with yeast expressing dsRNA targeting yTub23C, blw, Ace, or Rpl19 resulted in 100% survival in all treated and control groups (data not shown). To examine possible sublethal effects on fitness following the feeding treatment, we measured locomotor activity as a proxy for general health. Adult D. suzukii were fed for three days on live yeast expressing dsRNA targeting yTub23C, blw, Ace, or Rpl19, and then were placed into glass tubes for activity monitoring. Adult D. suzukii had decreased locomotor activity in the 4 days following treatment (Fig. 2c) and the greatest decrease in activity was observed in the treatment targeting yTub23C. Although activity levels were reduced in flies treated with dsRNA, flies in all treatments maintained typical temporal patterns of activity through the day (i.e. anticipation of dawn and dusk, and peak of activity at dusk) (Fig. 2d). We found that this effect on locomotor activity level persisted over the first four days following the feeding period, but the activity levels of the treated flies were not significantly different from the control flies by the fifth or sixth day following the feeding period (Fig. 2c). This result indicates the treated flies were able to recover from the dsRNA treatment. Due to the fact that the yeast expressing yTub23C dsRNA produced the greatest reduction in activity levels, all subsequent molecular and physiological assays were only performed using yTub23C-targeting yeast.

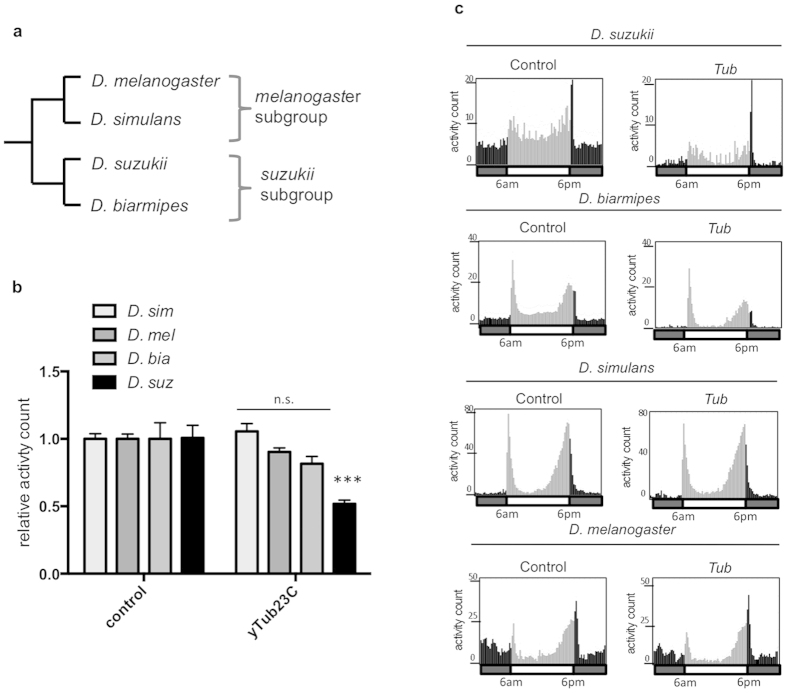

The effects of yeast feeding treatment on adult locomotor activity levels are species specific

One benefit of using RNAi in pest management is that RNAi triggers can be designed to target pest species while minimizing the risk of effects on beneficial insects46. To demonstrate this, we tested a D. suzukii dsRNA fragment selected from the non-conserved yTub23C 3’ untranslated region (UTR). We fed transformed yeast expressing dsRNA targeting D. suzukii yTub23C to other Drosophilids and found that even closely related species were unaffected by the treatments (Fig. 3b). D. biarmipes is closely related to D. suzukii, while D. melanogaster and D. simulans are more distant relatives (Fig. 3a). D. simulans, D. biarmipes, and D. melanogaster were unaffected by treatment with yeast expressing dsRNA targeting D. suzukii yTub23C. All species maintained regular temporal patterns of activity throughout the day (Fig. 3c). Homologous gene fragments were identified for each species by BLAST sequence alignment47, and sequence identity scores were calculated (Supplementary Table S1). The yTub23C target gene fragment was designed to be divergent by targeting the 3’ UTR and is 90% to 74% conserved between D. suzukii and the other Drosophilids tested. We predicted the yTub23C fragment would be less effective on species other than D. suzukii due to reduced base pair matching. The lack of an effect on activity in species other than D. suzukii suggests that a high degree of perfect base pair matching is required for RNAi response and to reduce locomotor activity. These results imply the mechanism responsible for this reduction in locomotor activity level is target sequence dependent. An alternative explanation for the differences in activity level between species following treatment could be that the dosage, i.e. feeding rate, varies by species, since the feeding assay was conducted ad libitum.

Figure 3. The effects of yeast feeding treatment on adult activity levels are species specific.

(a) Cladogram of melanogaster and suzukii subgroups. Only the species tested were included in the cladogram. (b) Relative locomotor activity levels in D. suzukii, D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. biarmipes following a three-day treatment with yeast expressing dsRNA against yTub23C. Activity was recorded using the DAMS during the 4 days following the treatment. Data represent averages and s.e.m. of 3 independent experiments, and a total of 96 flies were tested per treatment. Each replicate was normalized to the average of the control treatment. One-way ANOVA was performed (p = 0.0001) and significance relative to the control was determined by post hoc Dunnett corrected t-test (***indicates p < 0.001). (c) Activity levels plotted over the second day of recording following three days of feeding treatment. Each bar represents average activity counts in 15-minute increments. Black bars indicate lights off and grey bars indicate lights on. Presence or absence of light as well as the timing of light transition are also indicated in the horizontal bar underneath each activity graph; light turns on at 6am and turns off at 6pm each day of recording. Each eduction graph represents an average of 32 flies in one experiment. Representative eduction graphs are shown here.

Ingestion of yeast biopesticide alters expression level of target genes with subgroup specificity

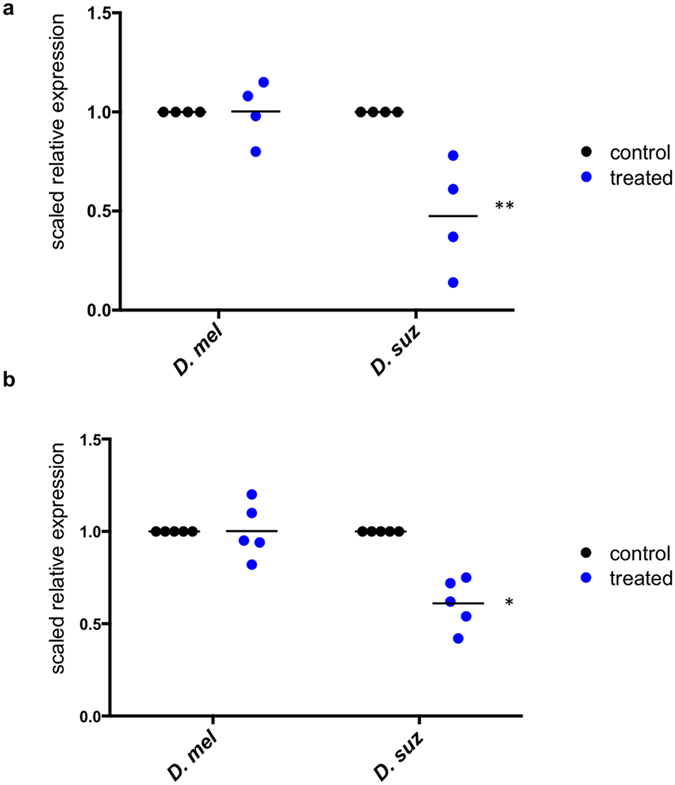

RNAi is not systemic in Drosophila, meaning RNAi only occurs within cells that come into contact with dsRNA48. We examined the midgut tissues post-treatment to measure changes in target gene expression in adults and larvae (Fig. 4a,b). D. suzukii larvae fed on yeast expressing dsRNA targeting yTub23C for 72 hours had significantly reduced yTub23C mRNA levels in the midgut (Fig. 4b). Adult D. suzukii midgut gene expression following yeast treatment was similar to the results in larvae, i.e. yTub23C expression level was significantly decreased (Fig. 4a). We did not find significant changes in target gene expression in D. melanogaster larva or adult midguts following 72-hour feeding treatments with yeast expressing dsRNA targeting D. suzukii yTub23C (Fig. 4a,b). The lack of change in target gene expression in D. melanogaster was not surprising, since we also observed no changes in locomotor activity. Moreover, larvae were subjected to a no-choice feeding assay, so differences in gene expression between D. suzukii and D. melanogaster larvae are not expected to depend on dosage.

Figure 4. Altered target gene expression in midgut following yeast feeding treatment.

Relative expression of target gene y-tubulin 23C in (a) adult midgut and (b) larval midgut following three days of treatment with yeast expressing dsRNA. Ten midguts were dissected and homogenized to obtain one RNA sample. Expression was quantified with RT-qPCR and was normalized against housekeeping gene cbp20. The expression level in the control is scaled to one and treated expression levels are plotted relative to the control. Each data point represents one biological replicate and the horizontal line indicates the mean. For (a) n = 4, and (b) n = 5. Significance relative to the control was determined by two-tailed t-test (*indicates p < 0.05, and **indicates p < 0.01).

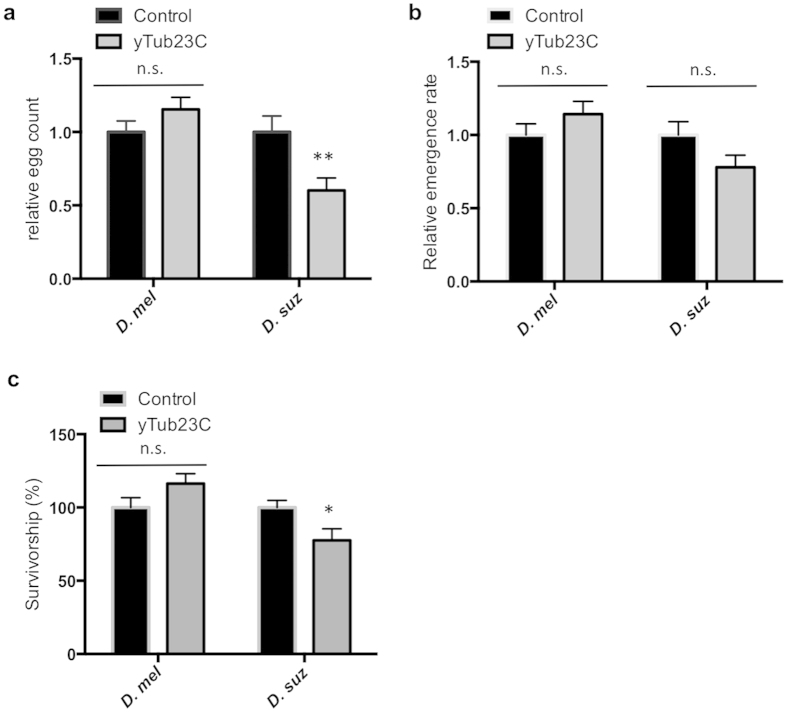

Ingestion of yeast biopesticide reduces reproductive fitness

Sublethal effects of pesticides, such as behavioral changes, general health decline, and decreased reproductive fitness, can lead to reduced population size within a region, minimizing crop losses49. To test if the yeast treatment affects reproductive fitness, we counted the number of eggs deposited per female post-treatment and measured the survival rate to adulthood of the offspring. We found that yeast expressing dsRNA that targets D. suzukii yTub23C caused significant decrease in the number of eggs laid by D. suzukii, but not by D. melanogaster (Fig. 5a). One possible explanation of this result is that induction of RNAi targeting yTub23C reduces overall fitness, so females are unable to devote resources towards producing eggs. An alternative explanation is that because treated flies are less active, the first mating is delayed compared to the control, resulting in fewer eggs at the end of the test period.

Figure 5. Yeast feeding treatment of adults and larvae decreases larval survivorship and adult reproductive fitness in a species specific manner.

(a) Relative egg counts of D. melanogaster and D. suzukii. Virgin females and males were fed separately on yeast expressing dsRNA against yTub23C for three days. One male and one female were crossed and allowed to lay eggs for 48 hours (D. melanogaster) or 72 hours (D. suzukii). (b) Relative emergence rate of D. melanogaster and D. suzukii eggs when parents were fed as described in (a). The hatch rate was determined by dividing the number of adults by the number of eggs recorded in that vial. Data shown in (a,b) represent mean and s.e.m. of three independent experiments and a total of 75 females were tested per treatment. Each replicate was normalized to the mean of the control and significance relative to the control was determined by a two-tailed t-test (**indicates p < 0.01). (c) Survivorship of D. melanogaster and D. suzukii 2nd instar larvae following 24 hour treatment with live yeast expressing dsRNA against yTub23C. Larvae were fed on a mixture containing 50% artificial diet and 50% live-pelleted yeast by volume. Mortality was assessed at the time of eclosion. Data shown in (c) represent mean and s.e.m. of six independent experiments and a total of 300 larvae were tested per treatment. Each replicate was normalized to the mean of the control and significance relative to the control was determined by a two-tailed t-test (*indicates p < 0.05).

We propose that the reduction in egg-laying by D. suzukii females following the transformed yeast feeding treatment is due to RNAi mediated disruption of yTub23C expression level. This altered expression level may cause cell death or dysfunction in the midgut, which could lead to decreased nutrition and general health decline. It is possible that disruption of midgut function can negatively impact nutritional input and reproduction, explaining the observed reduction in fecundity. We also hypothesized that decreased parental health following the yeast feeding treatment could lead to reduced viability of eggs. To test this hypothesis, we recorded survival rate to adulthood of eggs when the parents were treated with transformed yeast. The survival rates of the offspring of treated adults as measured by adult emergence rate were unaffected in both species (Fig. 5b).

Ingestion of yeast biopesticide decreases larval survivorship

Ingestion of yeast expressing dsRNA targeting D. suzukii yTub23C during the larval stages decreased survival to adulthood in D. suzukii, but not in D. melanogaster (Fig. 5c). Relative to the control treatment, which has a survival rate of 72%, the yTub23C treatment significantly reduced D. suzukii larval survival by 23% (Supplementary Table S2). The survival rate of D. melanogaster larvae subjected to the yTub23C treatment was not significantly different (Fig. 5c). Adult D. suzukii fed on yeast expressing dsRNA targeting yTub23C, Ace, RpL19, blw, and the control yeast had 100% survival over a ten-day feeding period (data not shown). Larvae consume a greater amount of food per day compared to adults. Since the larvae were fed in a no-choice assay, and the adults were fed with a choice between live transformed yeast and artificial diet, we reason that larvae likely received higher dosage of yeast. Differences in dosage could explain why the yeast feeding treatment induces mortality in larvae, but not in adults. Alternatively, we speculate larval stages could be more susceptible to RNAi than adults due to differences in the absorptive properties of the midgut or robustness of the RNAi pathway.

Discussion

Here we show that genetically modified yeast can be used to deliver dsRNA to an insect pest, causing decreased fitness through RNAi. Ingestion of this modified yeast by adult D. suzukii results in decreased locomotor activity and reduced egg-laying. Larvae exhibit reduced survival to adulthood when fed on yeast expressing dsRNA, and adults and larvae have decreased target gene expression following yeast feeding treatment. We find the effects of the yeast feeding treatment on target gene expression, survival, and reproductive fitness are subgroup specific, i.e. D. suzukii is negatively impacted while D. melanogaster is not. It should be noted that we did not perform experiments to confirm that dsRNA produced by the yeast was present within the insect cells following ingestion of the yeast. We found there was no feasible assay to separate the contents of the gut from the midgut cells and accurately detect exogenous transcripts coding for D. suzukii genes within D. suzukii cells. Additionally, it should be noted that the control yeast strain contains only empty plasmid and does not produce any dsRNA. Therefore, differences between the control and dsRNA treated samples may not be exclusively due to the effects of RNAi alone. It is possible that the dsRNA decreases fitness by inducing a sequence-independent response such as activation of the immune system, a phenomenon that has been observed in mammalian cells50. However, since species with divergent target gene sequences, such as D. simulans, were unaffected by the yeast feeding treatment, we find it unlikely that sequence-independent effects were responsible for the observed decreases in fitness. Changes in target gene expression following yeast-feeding treatment were observed in D. suzukii but not in D. melanogaster (Fig. 4). D. biarmipes, D. melanogaster, and D. simulans exhibited no changes in locomotor activity (Fig. 3b). Together, these results suggest that sequence-dependent target gene knockdown via RNAi was the primary cause of decreased fitness observed in D. suzukii.

This yeast biopesticide could be improved as a delivery vehicle by additional modifications to the yeast genome. A potential improvement to the current design could be to create modifications such that dsRNA is excreted from the yeast cells in membrane-bound vesicles. In the current design, dsRNA is expressed from circular DNA plasmids and remains within the cell. We hypothesize that dsRNA is absorbed into insect cells only when yeast cells are lysed within the insect midgut. It has been previously demonstrated that lipid encapsulated siRNA is more stable and more readily absorbed than naked siRNA51. Therefore, we predict continuous excretion of dsRNA in membrane bound-vesicles from intact yeast could increase the dosage and absorption of dsRNA into insect midgut cells.

The biosafety of this yeast biopesticide could be increased by adding a built-in mechanism of containment. A common concern with genetically modified organisms is their containment and potential negative impact on the environment. Yeast can be carried from one location to another by Drosophila, so it seems likely that genetically modified yeast could be spread beyond the boundaries of agriculture. Our design could be improved simply by placing the dsRNA under a promoter that requires the presence of an artificial molecule in order to prevent expression of dsRNA in the yeast where it is not wanted52. Recently, bacteria known as synthetic auxotrophs were engineered to only be viable in the presence of the synthetic molecule benzothiazole53, which prevents genetically modified bacteria from escaping and increases biosafety. However, benzothiazole is toxic and may pose additional problems for human safety. Another genetic modification technique has been used to create bacterial strains that require synthetic amino acids for growth54, which may be more suitable for environmental use. This technology could be applied to yeast biopesticides to prevent unwanted escapes.

We predict that this yeast biopesticide could be successfully implemented in the field to combat D. suzukii. The emergence of insecticide resistance and increasing popularity of organic food products may open the door to non-chemical means of pest control in both organic and conventional farming. A method for administering this yeast biopesticide in the field has already been presented, since yeast baited traps have previously been used in berry crops to lure D. suzukii40. Additionally, there is precedence for the agricultural use of genetically modified fungi, as the USDA has issued 26 permits for environmental release of genetically modified fungi since 199555. A major limitation of the current design is that mortality is not induced in adults. However, we found that this yeast biopesticide significantly decreases egg-laying and therefore could decrease the population size of the next generation. This yeast biopesticide could be used in complement with chemical pesticides by targeting detoxification genes rather than critical genes, a strategy that has proven effective for increasing susceptibility of mosquito larvae to insecticides24. By altering expression of detoxification genes, D. suzukii could be made more susceptible to chemical pesticides. As different types of insecticide resistance emerge, the genes targeted by the yeast could easily and quickly be changed to compensate. Further screening and validation is required to identify target genes that will have the greatest efficacy and produce high level of lethality when knocked down in the field. Targeting multiple genes simultaneously may also increase toxicity of this biopesticide, although a recent study conducted in Tribolium castaneum found that the effects of targeting multiple genes are not synergistic56.

Another characteristic of yeast that makes it an interesting candidate for a biopesticide is that unlike chemical pesticides, it can be easily grown with commonplace starting materials. Currently, live S. cerevisiae, commonly known as brewer’s yeast, can be purchased in packets from any grocery store. The yeast in these packets is dry and does not require refrigeration. We envision that in the future, a yeast biopesticide could be similarly packaged and distributed to farmers in developing countries, where it could be cultured at the site of use.

This yeast biopesticide design could be adapted to deliver dsRNA to other insect pests that associate with yeast. Many interactions have been observed between wild yeasts and insect species within Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera57. In fact, this biopesticide design may have greater use in managing an insect pest that both consumes yeast and has systemic RNAi.

A limitation of all RNAi-based technology is potential off-target effects. Only partial complementarity between the guide strand and the endogenous mRNA is required to prevent translation, so silencing of related transcripts in humans and other non-target species is a concern. Non-target arthropod species that have systemic RNAi mechanisms may especially be at risk, and many of these species do not have genomic data available to facilitate the design of pest-specific dsRNAs46. In addition to sequence-dependent off-target effects, introduction of dsRNA into mammalian cells can have sequence-independent effects on the immune system58. For example, dsRNA can activate an innate immune response in mammals, resulting in increased levels of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interferons50. In this pathway, dsRNA binds and activates protein kinase R, which phosphorylates and deactivates eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2, thereby inhibiting translation in cells that contain dsRNA59. Since these effects on the immune system are not dependent on the sequence of the dsRNA, even careful selection of target sequences cannot mitigate these off-target effects. Pesticides containing dsRNA will need further testing to determine safety for non-target arthropods and for human consumption.

Methods

Animal Models

For all insect bioassays, the researcher was blinded from the identity of the treatment during the course of the experiment. Insects were assigned to treatment groups by pooling same-aged individuals from several rearing bottles and randomly redistributing into groups. A different generation of flies was used in each experimental replicate.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.0f. The student’s t-test was used in assays that compared two groups. For assays with more than two groups, one way or two-way ANOVA was performed using 95% confidence intervals to determine significance. Significance relative to control treatments was determined by post hoc t-test with Dunnett correction for multiple comparisons. To allow for comparisons between species, each data point or replicate is normalized to the mean of the same-species control group (Figs 3b and 5)60.

Fly strains and rearing

All Drosophila species and strains tested in our studies as well as their collection sites are listed in Supplementary Table S3. All lines were maintained in Fisherbrand square, polyethylene, 6 oz. stock bottles (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) containing 50 ml of Bloomington stock center Drosophila food recipe. Colonies were kept between 22 °C–25 °C in a cabinet incubation chamber (Percival Scientific, Inc., Perry, IA) with a 12:12 h light:dark cycle.

Target gene selection for double stranded RNA (dsRNA) knockdown

Target genes were selected based on four main criteria: gene essentiality, midgut expression level, degree of divergence from related species sequences (Supplementary Table S1), and target effectiveness demonstrated in previous studies. We assumed that genes with essential functions in D. melanogaster would also have essential functions in D. suzukii. Genes with lethal null phenotypes recorded in Flybase.org were considered essential. We hypothesized that the dsRNA produced by the yeast would be absorbed by the midgut tissues in the fly, so we selected target genes that are expressed in the adult and larval midgut. Midgut expression was determined using the FlyAtlas database of microarray data61. Conservation of target sequences between species was also considered when selecting gene fragments. The D. suzukii y-tubulin 23C (yTub23C) target sequence was designed to be highly divergent from members of the melanogaster subgroup by targeting the 3’ untranslated region (UTR). The bellwether (blw), Ribosomal protein L19 (RpL19), and acetylcholine esterase (Ace) target sequences were chosen from coding regions and are more conserved across species. Alignments of target gene fragment sequences (Supplementary Fig. S1) for D. suzukii, D. biarmipes, D. melanogaster, and D. simulans and identity scores (Supplementary Table S1) were generated with ClustalW262. Whyard et al.20 demonstrated that tubulin is an effective RNAi target in Drosophila, and dsRNA targeting blw and RpL19 caused increased cell death in D. melanogaster tissue culture experiments63, so we selected homologous target gene fragments from D. suzukii sequences. Chemical pesticides commonly disrupt neurotransmission by inhibiting the function of acetylcholine esterase, so we chose to target this gene as well. Target gene fragment sequences are listed in Supplementary Fig. 2. Spotted Wing Flybase accession numbers were used as identifiers and sequences can be retrieved from Spotted Wing Flybase (http://spottedwingflybase.oregonstate.edu/).

Construction of vectors for in vitro synthesis of dsRNA

1 μg of D. suzukii total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Target gene fragments y-tubulin 23C and Vacuolar H+-ATPase 26 kD subunit were PCR amplified from D. suzukii total cDNA using AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following manufacturer’s specifications and ligated into pCR2.1 using the TA Cloning Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The primer sequences used for molecular cloning are listed in Supplementary Table S4. The T7 promoter sequence (5′- TAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′) was added to the 5’ end of the forward and reverse primer sequences.

In vitro RNA synthesis

Target gene fragments y-tubulin 23C and vacuolar H+-ATPase 26 kD subunit were PCR amplified from pCR2.1 vectors containing the target sequences and convergent T7 promoters. PCR products were purified with the QiaQuick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified PCR product was used as template for in vitro transcription using the MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were quantified with a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and quality was assessed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel.

Construction of plasmid vectors for expression of dsRNA in yeast

Yeast expression vectors containing inverted repeats of ~200 bp D. suzukii target gene sequence joined by a 74 bp intron sequence from the D. melanogaster white gene were constructed in two cloning steps. The intron and the target sequence were inserted in the forward orientation in the first step, and the target sequence was inserted in the reversed orientation in the second step. Target gene fragments y-tubulin 23C, bellwether, acetylcholine esterase, and ribosomal protein L19 were PCR amplified from D. suzukii total cDNA using AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following manufacturer’s specifications. A BamHI restriction site was added to the 5’ end of the forward primer sequence, and a EcoRI restriction site was added to the 5’ end of the reverse primer sequence (see Supplementary Table S4 for primer sequences). The second intron of the white gene was PCR amplified from D. melanogaster total cDNA using primers with a BamHI restriction site added to the 5’ end of the forward and a EcoRI site added to 5’ end of the reverse primer. PCR products were purified with the QiaQuick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and target sequences were digested with restriction enzymes BamHI and Xba1, and the white intron was digested with BamHI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA). The S. cerevisiae expression vector p406TEF1 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) was digested with Xba1 and EcoRI. Digested PCR products and vector DNA were purified with gel electrophoresis and the QiaQuick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. The vector, target sequence, and intron were ligated together with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA). Ligation products were transformed into E. coli and plasmid DNA was extracted from the clones. Sequencing was performed to confirm presence of the forward target sequence and the intron. Target gene fragments were amplified from the confirmed DNA clones using a reverse primer with EcoRI on the 5’ end and a forward primer with HindIII on the 5’ end. Confirmed DNA clones were restriction digested with EcoRI and HindIII. Digested PCR products and DNA vectors were gel purified and ligated together with T4 DNA ligase. The complementary sequences in the completed vectors created secondary structure that prevented Sanger sequencing, so completed clones were restriction digested with Xba1 and EcoRI, or BamHI and HindIII, and gel purified digestion products were used for sequencing for confirmation of successful expression vector construction.

Transformation of plasmids into S. cerevisiae

DNA vector p406TEF1 containing inverted repeats of D. suzukii target gene sequence were transformed into S. cerevisiae strain INVSc1 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) using the Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation kit II (Zymo, Irvine, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Transformants were selected on minimal media without uracil and confirmed by colony PCR. PCR reactions were performed as described above with a forward primer located upstream of the multiple cloning site and the reverse primer located within the white intron.

Isolation of RNA from yeast

1.5 mL liquid yeast culture was pelleted at 12,000 rpm for 1 minute. 300 μl of TRI-reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added to the pellet and homogenized by vortexing with 100 μl acid-washed 425–600 μm glass beads (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). One-fifth volume of 100% chloroform was added to each sample and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The upper aqueous layer was collected and nucleic acid was precipitated by adding an equal volume of 100% isopropanol and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C, and pellets were washed once with two volumes of 70% ethanol. Pellets were resuspended in 20 μl 1× Turbo DNase buffer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and treated with 1 μl Turbo DNase following manufacturer’s instruction. RNA concentrations were quantified with a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Treatment of larvae with in vitro transcribed dsRNA

2nd instar larvae were separated from fly food and rinsed with water. 100 μl of a solution containing 1 mg/ml in vitro transcribed dsRNA, 3% Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was pipetted onto a plastic dish forming a droplet. The control solution contained Lipofectamine and Schneider’s Drosophila medium only. 10 larvae were gently added to each droplet and soaked for 1 hour. Larvae were returned to a small dish of fly food and mortality was assessed 24 hours later and at the time of eclosion. Larvae were collected for RNA isolation at the same time-point when mortality was assessed. Three independent experiments were performed using larvae from three separate generations, and 50 to 60 larvae were tested per treatment in each replicate experiment.

Transformed yeast feeding assay for adults and larvae

Yeast colonies expressing dsRNA were incubated in 4 ml minimal media without uracil at 30 °C and 225 rpm for 24 hours. 4 ml cultures were used to inoculate 300 ml cultures and incubated at 30 °C for 24 hours. Liquid culture was pelleted at 5,000 rpm for 15 minutes. To feed larvae, pelleted yeast was mixed with standard Bloomington Drosophila fly food medium at a ratio of 1:1 by weight and fed to larvae in 12- well tissue culture plates. 1 mL of food and yeast mixture and twenty larvae were added to each well. After yeast feeding period, larvae were transferred to a vial containing standard Bloomington Drosophila medium to grow to adulthood, or were collected for RNA isolation. Larvae were fed for 24 hours for survival assays, and for 24 hours or 72 hours for gene expression assays. To quantify survival, larvae were fed on yeast for 24 hours and transferred to a vial in groups of 20. A moistened lab wipe was added to each vial to increase the humidity and provide a surface for pupation. The number of adults that emerged from each vial was used as a measure of survival.

To feed adults, pelleted yeast was spread thinly on a wooden tongue depressor coated in YPD agar (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The yeast-covered tongue depressor was imbedded upright in a vial containing standard Bloomington Drosophila medium and 30 adult flies were added to each vial.

To confirm the adults and larvae ingest the yeast, red food coloring was added to the liquid yeast culture (McCormick), and midguts were dissected and inspected visually under a light microscope. The control diet was standard Bloomington Drosophila medium without food coloring. Five adult midguts or larval midguts were dissected for each treatment. This experiment was performed twice.

Locomotor activity monitoring

Male adult flies were used for activity assays because females present technical difficulties, e.g. larvae and eggs interfere with infrared monitoring and gravid females exhibit different activity profiles than non-gravid females. Flies were loaded individually into glass tubes for activity monitoring using Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (DAMS) (Trikinetics, Waltham, MA) following three days of yeast feeding treatment. The glass tubes were filled at one end with media containing 5% agar and 2% sucrose by weight. Percival incubators were set to 25 °C with a photoperiod of 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark. Fly activity monitoring and data analysis were performed using DAMS and FaasX respectively64. Briefly, the DAMS consists of a infrared beam positioned to intersect the glass tube housing a single fly. When the fly travels from one end of the tube to the other, the infrared beam is broken and the DAMS records one activity count.

Assessment of fecundity and viability of offspring

Standard Bloomington Drosophila medium was dyed green with food coloring (McCormick) to provide visual contrast to eggs. 1 ml of hot media was pipetted onto a small plastic spoon and allowed to cool. Once solidified, media was painted with a thin layer of wild type S. cerevisiae grown in liquid culture to encourage oviposition. Spoons were placed inside empty fly vials (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA). Adult males and virgin females were fed on transformed yeast expressing dsRNA for three days. Following the feeding period, one male and one female were added to the vial containing the spoon. After the egg-laying period, eggs were counted visually under a stereomicroscope. The spoon was transferred to a vial containing Drosophila medium and eggs were allowed to grow to adulthood. Survival rates were calculated by dividing the number of emerged adults by the number of eggs recorded in each vial.

Isolation of RNA from adult and larval midgut

Following yeast feeding treatment, live adults were anesthetized with carbon dioxide and live larvae were separated from yeast mixture. Adults and larvae were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing TRI-reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and kept on ice. Dissection of the midgut was performed immediately on ice in chilled RNAlater (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Midguts were washed 2× in chilled nuclease-free water and 300 μl TRI-reagent was added to the microcentrifuge tube. Midguts were homogenized by grinding using a motorized pestle and RNA isolation was performed as described above in the section on “yeast RNA isolation”.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

1 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Dilutions (1:10) of cDNA samples were used in qRT-PCR reactions. Gene-specific primers were designed based on sequence analysis using the D. suzukii genome scaffold and optimized at an annealing temperature of 63.3 °C. The primer efficiencies for D. melanogaster yTub23C and D. suzukii yTub23C were 99.1% and 100.2% respectively. Melt curve and BLAST analysis were used as criteria to determine primer specificity. The qRT- PCR assays were performed using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA) in a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cycling conditions were 95 °C for 30 seconds, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 seconds, followed by an annealing/extension phase at 63.3 °C or 55 °C for 30 seconds. The reaction was concluded with a melt curve analysis going from 65 °C to 95 °C in 0.5 °C increments at five seconds per step. Three technical replicates were performed for each data point of each biological replicate, and at least 4 biological replicates were performed for analysis of each gene. Data were analyzed using the standard ∆∆Ct method and target gene mRNA expression levels were normalized to the reference gene Cbp20 mRNA levels65,66. Finally, average relative expression values for treated samples were divided by the average control values to represent the fold change of target gene expression in the treated sample65.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Murphy, K. A. et al. Ingestion of genetically modified yeast symbiont reduces fitness of an insect pest via RNA interference. Sci. Rep. 6, 22587; doi: 10.1038/srep22587 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the UC San Diego Drosophila Stock Center for providing Drosophila species and strains. D. suzukii from Watsonville, CA, U.S.A. were collected with permission by Garroutte Farms, Inc. in 2008 (Watsonville, CA). We thank Frank Zalom, Kelly Hamby, Nicolas Svetec and Kyria Boundy-Mills for fruitful discussions. This work is supported by the California Cherry Board Grant CCB5400-004 and the Clarence and Estelle Albaugh Endowment to JCC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: K.A.M., C.A.T. and J.C.C. Performed the experiments: K.A.M., C.A.T. and K.R.C. Analyzed the data: K.A.M. and K.R.C. Wrote the manuscript: K.A.M. and J.C.C.

References

- Coy M. R. et al. Gene silencing in adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes through oral delivery of double-stranded RNA. J. Appl. Entomol. 136, 741–748 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch A. & Moritz R. F. Systemic RNA-interference in the honeybee Apis mellifera: Tissue dependent uptake of fluorescent siRNA after intra-abdominal application observed by laser-scanning microscopy. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 851–857 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Long dsRNA but not siRNA initiates RNAi in western corn rootworm larvae and adults. J. Appl. Entomol. 139, 432–445 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Khan S. A., Hasse C. & Ruf S. Full crop protection from an insect pest by expression of long double-stranded RNAs in plastids. Science. 347, 991–994 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J. M. et al. Extension of Drosophila life span by RNAi of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Curr. Biol. 19, 1591–1598 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum J. a. et al. Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1322–1326 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutti N. S., Park Y., Reese J. C. & Reeck G. R. RNAi knockdown of a salivary transcript leading to lethality in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect Sci. 6, 1–7 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Wheeler M. M., Oi F. M. & Scharf M. E. RNA interference in the termite Reticulitermes flavipes through ingestion of double-stranded RNA. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 805–815 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li H., Guan R. & Miao X. Lepidopteran insect species-specific, broad-spectrum, and systemic RNA interference by spraying dsRNA on larvae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 155, 218–228 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Zheng W., Zheng W. & Zhang H. The effects of RNA interference targeting Bactrocera dorsalis ds-Bdrpl19 on the gene expression of rpl19 in non-target insects. Ecotoxicology 24, 595–603 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obbard D. J., Gordon K. H. J., Buck A. H. & Jiggins F. M. The evolution of RNAi as a defence against viruses and transposable elements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 364, 99–115 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H. & Rossi J. J. RNAi mechansims and applications. Biotechniques. 44, 613–616 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellés X. Beyond Drosophila: RNAi in vivo and functional genomics in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 111–128 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotti M. J. & Smagghe G. RNAi technology for insect management and protection of beneficial insects from diseases: lessons, challenges and risk assessments. Neotrop. Entomol. 44, 107–213 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burand J. P. & Hunter W. B. RNAi: Future in insect management. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 112, S68–74 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon K. H. J. & Waterhouse P. M. RNAi for insect-proof plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1231–1232 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M. et al. The endocytic pathway mediates cell entry of dsRNA to induce RNAi silencing. Cell 8, 793–802 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzitoyeva S., Dimitrijevic N. & Manev H. Intra-abdominal injection of double-stranded RNA into anesthetized adult Drosophila triggers RNA interference in the central nervous system. Mol Psychiatry 6, 665–670 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplen N. J., Fleenor J., Fire A. & Morgan R. A. dsRNA-mediated gene silencing in cultured Drosophila cells: a tissue culture model for the analysis of RNA interference. Gene 252, 95–105 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyard S., Singh A. D. & Wong S. Ingested double-stranded RNAs can act as species-specific insecticides. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 824–832 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y. B. et al. Silencing a cotton bollworm P450 monooxygenase gene by plant-mediated RNAi impairs larval tolerance of gossypol. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1307–1313 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Miguel K. & Scott J. G. The next generation of insecticides: dsRNA is stable as a foliar-applied insecticide. Pest Manag. Sci. Epub ahead of print. (2015). doi: 10.1002/ps.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Guan R., Guo H. & Miao X. New insights into an RNAi approach for plant defence against piercing-sucking and stem-borer insect pests. Plant. Cell Environ. Epub ahead of print. (2015). doi: 10.1111/pce.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhang J. & Zhu K. Y. Chitosan/double-stranded RNA nanoparticle-mediated RNA interference to silence chitin synthase genes through larval feeding in the African malaria mosquito (Anopheles gambiae). Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 683–693 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H. et al. Developmental control of a lepidopteran pest Spodoptera exigua by ingestion of bacteria expressing dsRNA of a non-midgut gene. PLoS One 4, e6225 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F., Xu J., Palli R., Ferguson J. & Palli S. R. Ingested RNA interference for managing the populations of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 175–182 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taracena M. L. et al. Genetically modifying the insect gut microbiota to control Chagas disease vectors through systemic RNAi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003358 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starmer W. T. A Comparison of Drosophila habitats according to the physiological attributes of the associated yeast communities. Soc. Study Evol. 35, 38–52 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher P. G. et al. Yeast, not fruit volatiles mediate Drosophila melanogaster attraction, oviposition and development. Funct. Ecol. 26, 822–828 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Scheidler N. H., Liu C., Hamby K. A., Zalom F. G. & Syed Z. Volatile codes: Evolution of olfactory signals and reception in Drosophila-yeast chemical communication. Sci. Rep. 5, 14059 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanca L., Gaskett A. C., Günther C. S., Newcomb R. D. & Goddard M. R. Quantifying variation in the ability of yeasts to attract Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 8, e75332 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B. R., Yazgan O. & Krebs J. E. Life without RNAi: noncoding RNAs and their functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 767–779 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starmer W. T., Peris F. & Fontdevila A. The transmission of yeasts by Drosophila buzzatii during courtship and mating. Anim. Behav. 36, 1691–1695 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio A. E., Rodriguez R. K., Kernan M. J. & Neiman A. M. The yeast spore wall enables spores to survive passage through the digestive tract of Drosophila. PLoS One 3, e2873 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C. et al. The susceptibility of small fruits and cherries to the spotted-wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 1358–1367 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplen M. K., Anfora G. & Biondi A. Invasion biology of spotted wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): a global perspective and future priorities. J Pest SC 88, 469–494 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. B. et al. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): Invasive pest of ripening soft fruit expanding its geographic range and damage potential. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2, 1–7 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bolda M. P., Goodhue R. E. & Zalom F. G. Spotted Wing Drosophila: Potential economic impact of a newly established pest. Agric. Resour. Econ. Updat. Univ. California. Giannini Found. 13, 5–8 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J. C. et al. Genome of Drosophila suzukii, the Spotted Wing Drosophila. G3-Genes Genomes Genet. 3, 2257–2271 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias L. E., Nyoike T. W. & Liburd O. E. Effect of trap design, bait type, and age on captures of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in berry crops. Hortic. Entomol. 107, 1508–1518 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby K. A., Hernández A., Boundy-Mills K. & Zalom F. G. Associations of yeasts with spotted-wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii; Diptera: Drosophilidae) in cherries and raspberries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4869–4873 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J. & Zeng F. Feeding-based RNA intereference of a gap gene is lethal to the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS One 7, e48718 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe D. P., Lehane S. M., Lehane M. J. & Haines L. R. Prolonged gene knockdown in the tsetse fly Glossina by feeding double stranded RNA. Insect Mol. Biol. 18, 11–19 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuriyanghan H., Rosa C. & Falk B. W. Oral delivery of double-stranded RNAs and siRNAs induces RNAi effects in the potato/tomato psyllid, Bactericerca cockerelli. PLoS One 6, e27736 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L. & Linsley P. S. Noise amidst the silence: Off-target effects of siRNAs? Trends Genet. 20, 521–524 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren J. G. & Duan J. J. RNAi-based insecticidal crops: potential effects on nontarget species. Bioscience 63, 657–665 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S., Gish W. & Miller W. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roignant J.-Y. et al. Absence of transitive and systemic pathways allows cell-specific and isoform-specific RNAi in Drosophila. RNA 9, 299–308 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes K. F. Sublethal effects of neurotoxic insectidices on insect behavior. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 33, 149–168 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins M., Judge A. & MacLachlan I. siRNA and innate immunity. Oligonucleotides 19, 89–102 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lu Z., Wientjes M. G. & Au J. L.-S. Delivery of siRNA therapeutics: barriers and carriers. AAPS J. 12, 492–503 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIsaac R. S., Gibney P. A., Chandran S. S., Benjamin K. R. & Botstein D. Synthetic biology tools for programming gene expression without nutritional perturbations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e48 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G. & Anderson J. C. Synthetic auxotrophs with ligand-dependent essential genes for a BL21(DE3) biosafety strain. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 1279–1286 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner A. J. et al. Recoded organisms engineered to depend on synthetic amino acids. Nature. 518, 89–93 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson K. E., Dawson W. O., Handler A. M., Schetelig M. F. & St. Leger R. J. Not all GMOs are crop plants: non-plant GMO applications in agriculture. Transgenic Res. 23, 1057–1068 (2013). doi: 10.1007/s11248-013-9769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich J. et al. Large scale RNAi screen in Tribolium reveals novel target genes for pest control and the proteasome as prime target. BMC Genomics 16, 674 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F. S ymbiosis between yeasts and insects. Introd. Pap. Fac. Landsc. Archit. Horiculture, Crop Prod. Sci. 1–52 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda P. Off-targeting and other non-specific effects of RNAi experiments in mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 9, 248–257 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire P. A., Anderson E., Lary J. & Cole J. L. Mechanism of PKR activation by dsRNA. J Mol Biol. 381, 351–360 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcu M. & Valcu C. M. Data transformation practices in biomedical sciences. Nat. Methods 8, 104–105 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli V. R., Wang J. & Dow J. A. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 715–720 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. a. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros M. et al. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of growth and viability in Drosophila cells. Science 303, 832–835 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J. C., Low K. H., Pike D. H., Yildirim E. & Edery I. Assaying locomotor activity to study circadian rhythms and sleep parameters in Drosophila. J. Vis. Exp. 28, 1–8 (2010). doi: 10.3791/2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majercak J., Chen W. & Edery I. Splicing of the period gene 3′ terminal intron is regulated by light, circadian clock factors, and phospholipase C. 24, 3359–3372 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.