Abstract

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) remains enigmatic, despite some 1.4 million cases worldwide annually1. It differs radically from other picornaviruses, existing in an enveloped form2 and being unusually stable, both genetically and physically3, but has proved difficult to study. We report high-resolution X-ray structures for the mature virus and empty particles. The structures of the two particles are indistinguishable, apart from some disorder on the inside of the empty particle. The full virus contains the small viral protein VP4, while the empty particle harbors only the uncleaved precursor, VP0. The smooth particle surface is devoid of depressions which might correspond to receptor binding sites. Peptide scanning data extends the previously reported VP3 antigenic site4, while structure-based predictions5 suggest further epitopes. HAV contains no pocket factor, can withstand remarkably high temperature and low pH, with empty particles being even more robust than full particles. The virus probably uncoats via a novel mechanism, being built differently to other picornaviruses. It utilizes a VP2 ‘domain swap’ characteristic of insect picorna-like viruses6,7 and structure-based phylogenetic analysis places HAV between typical picornaviruses and the insect viruses. The enigmatic properties of HAV may reflect its position as a link between ‘modern’ picornaviruses and the more ‘primitive’ precursor insect viruses, for instance HAV retains the ability to move from cell-to-cell by transcytosis8,9.

HAV is unique amongst picornaviruses in targeting the liver and continues to be a source of mortality despite a successful vaccine10. HAV isolates belong to a single serotype11. Unlike other picornaviruses HAV cannot shut down host protein synthesis, has a highly deoptimized codon usage and grows poorly in tissue culture. Particles are produced with a 67 residue C-terminal extension of VP1, which is implicated in particle assembly (this longer form of VP1 is known as VP1-2A or PX)12. Particles containing the extension shroud themselves in host membrane to create enveloped viruses2. The extension is cleaved by host proteases to yield mature capsids12. Whilst picornavirus VP4 is generally myristoylated this does not happen in HAV13, indeed the putative VP4 is very small (~23 residues13) and it has remained unclear if it is present in virus particles14. The cell surface molecule T cell Ig and mucin 1 (TIM-1)15 acts as a receptor for HAV, and although transcytosis occurs8,9 it is not clear how the virus gets to the liver, its principal site of replication.

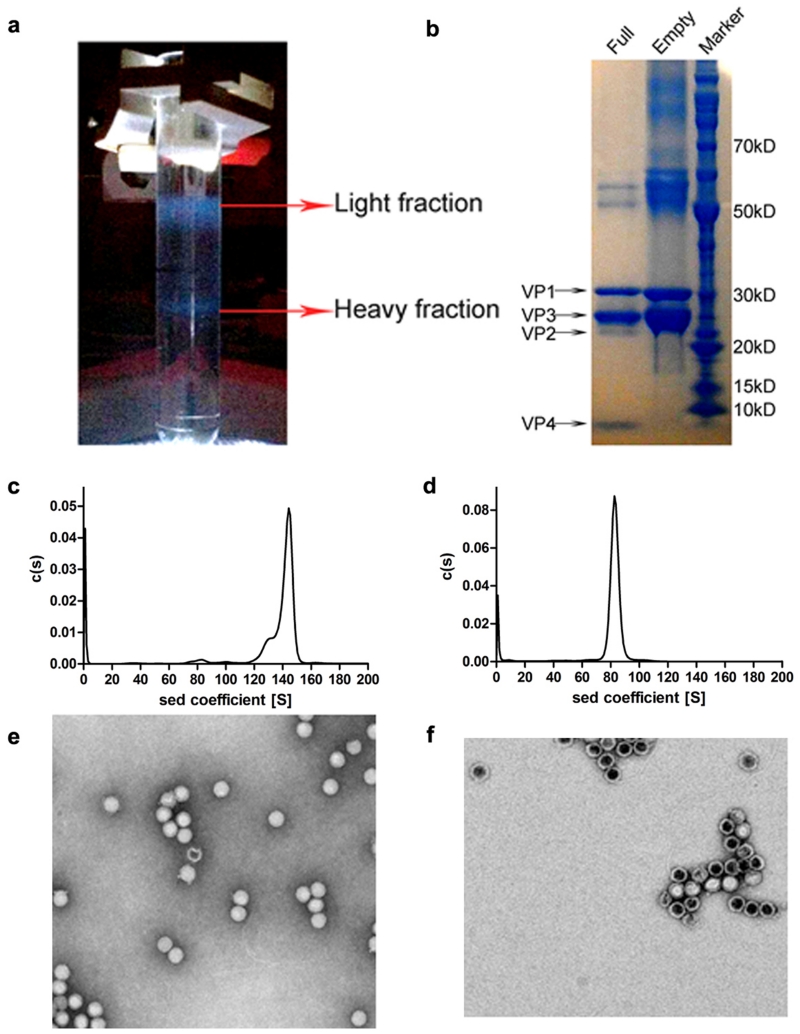

We have analysed formaldehyde inactivated HAV genotype TZ84 (Methods). Two types of particles were separated, one containing significant amounts of viral RNA (Extended Data Fig. 1). In the RNA-containing full particles VP0 is at least partially cleaved and we detect VP4, as for other picornaviruses, whilst the empty particles harbour only VP0, and are probably similar to the empty particles frequently seen in picornavirus infections (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1). It remains unclear whether such empty particles can encapsidate RNA and lie on the route to assembly of full particles. Even full particles appear to contain more uncleaved VP0 than is seen in other picornaviruses, in-line with observations that VP0 cleavage is ‘protracted’16. The sedimentation coefficients are circa 144S and 82S for the full and empty particles respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1). 144S is a little less than the 155S expected for a full enterovirus particle while the empty particle has a similar S-value to that observed for the more expanded empty enterovirus particles17.

Very thin crystals (~100×100×5 μm3) were obtained for both particles. Diffraction data were collected at Diamond beamlines I03 and I24. Data were collected at 100K to avoid beam induced crystal movement at room temperature (Supplementary Video 1), and were used to produced reliable atomic models at 3.0 and 3.5 Å resolution for the full and empty particles respectively (Methods and Extended Data Table 1).

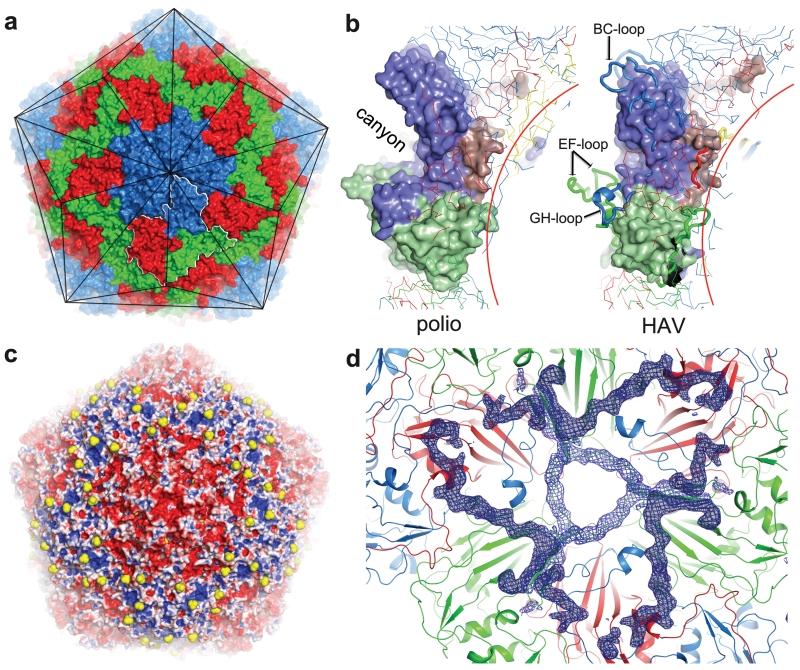

The external surface of HAV is smooth, with no canyon (Fig. 1a)18; shortening of the VP1 BC loop lowers the north wall while reductions in the VP2 EF and VP1 GH loops ablate the south wall of the canyon (Fig. 1b). Compared to foot-and-mouth-disease virus, the loops at the 5-fold and 3-fold axes in HAV are slightly raised, giving the virus the appearance of a facetted triakis icosahedron (Fig. 1a). In-line with the low buoyant density in CsCl19 there are no apertures in the capsid to permit the entry of Cs+ ions. The major capsid proteins, VP1-3 comprise eight-stranded anti-parallel β-barrels, follow the expected pseudo T=3 arrangement and span the thickness of the capsid (Extended Data Fig. 2a-c). The HAV full virus is mostly well-ordered (however VP4, although present, is not visible). As expected there is no evidence for structural modification attributable to formaldehyde inactivation17.

Figure 1. Overall structure.

a, HAV accessible surface (VP1: blue, VP2: green, VP3: red for all panels). Black lines: particle facets, white outline: biological protomer. b, Surface of the biological protomer of HAV and poliovirus. Loops forming the canyon walls in poliovirus are drawn thicker. c, HAV electrostatic surface (using APBS in PyMOL). Red negative, blue positive, white neutral, sulphate ions yellow. d, HAV viewed from inside. Blue positive |Fo-Fc| electron density calculated taking the correctly positioned empty HAV from the full HAV shows that VP1 2-28 (darker density) and VP2 5-17 are better defined in the full particle.

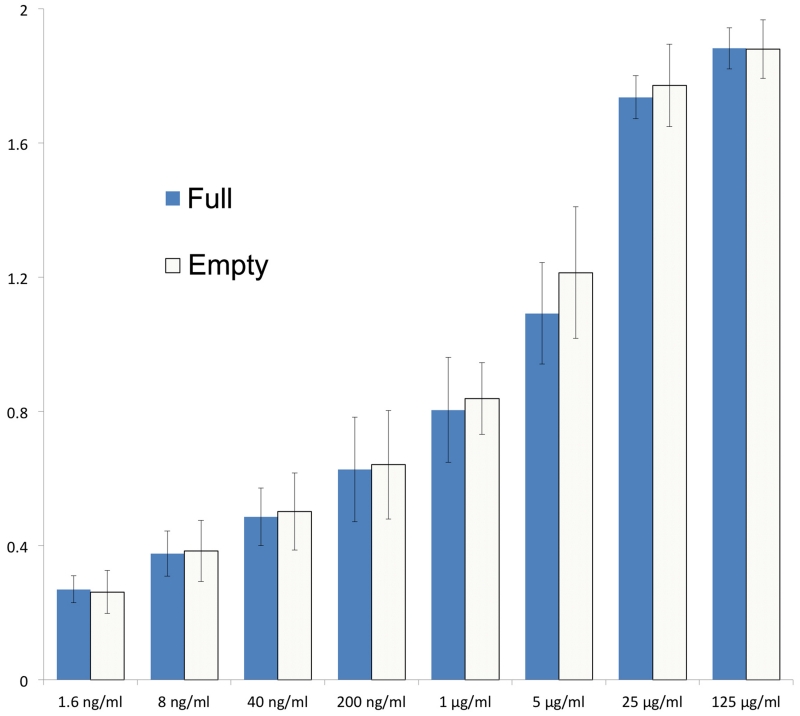

The empty and full particles are mostly very similar, with the external surface expected to be antigenically indistinguishable (RMSD for 672 Cα atoms 0.2 Å). Experiments with six antibodies confirmed this (Extended Data Fig. 3). The particle surface is remarkably negatively charged (Fig. 1c) and the fringes of the pentameric assemblies, which show some positive charge, are decorated with a string of sulphate ions derived from the crystallization media. Surface decoration may affect the hydrodynamic properties of the particles. In the empty particle the first 40 residues of VP0 and 47 residues of VP1, which festoon the particle interior near the three-fold axes are disordered (Fig. 1d). Although neither particle contains the extended form of VP1 we can infer the point on the particle surface from which the extension would continue (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

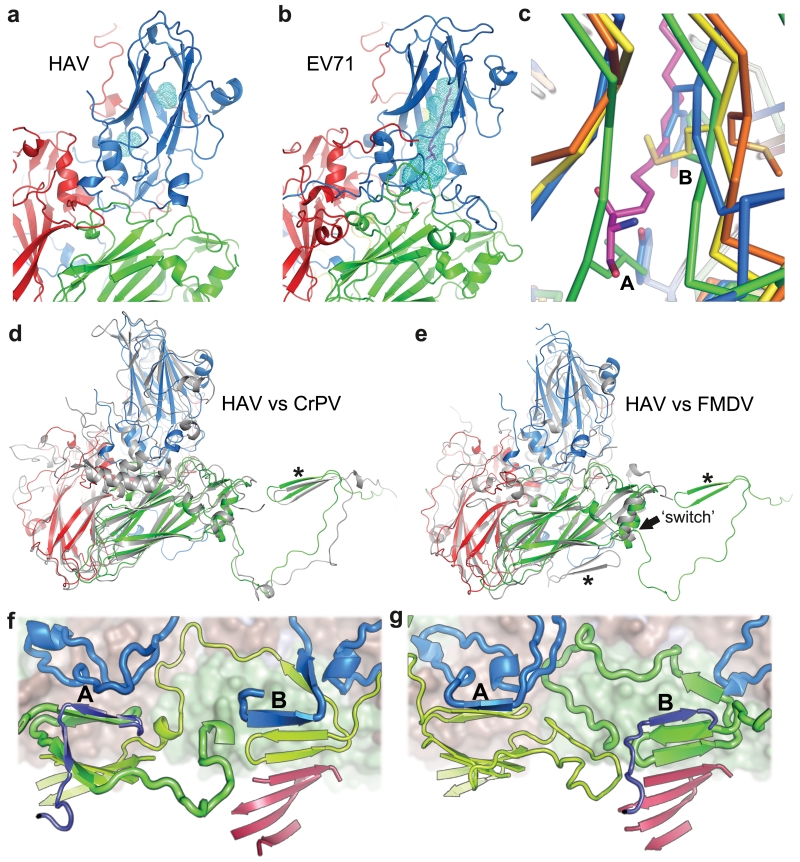

Perhaps correlated with the lack of a canyon, HAV harbors no contiguous hydrophobic pocket in the VP1 β-barrel. The β-barrel is compressed compared to enteroviruses,20 and the remaining space largely filled with hydrophobic side-chains, as in aphtho and cardioviruses21 (Fig. 2a-c). In addition, lengthened βC and βH strands essentially cover what would be the entrance to the pocket. We conclude that HAV is unable to bind small molecules in the fashion characteristic of enteroviruses. Unfortunately the particle structure provides no immediate clues as to where the TIM-1 receptor15 might attach.

Figure 2. Structure features.

a HAV and b EV71 coloured as 1a, light blue mesh: pocket-volume calculated with PyMOL. Magenta: EV71 pocket factor. c, Pocket close-up, left strand C, right H, for: HRV14 (yellow), FMDV (blue), EV71 (orange, pocket factor magenta) and HAV (green, note occlusion of pocket entrance). Met224 occludes part of the empty HRV14 pocket. A and B: bulky side-chains occlude the HAV and FMDV pockets (A: Leu-HAV, Tyr-FMDV, B: Phe-HAV and Tyr-FMDV). d, e, Biological protomers of CrPV and FMDV respectively superimposed on HAV. The star marks the VP2 N-terminus that folds differently in FMDV (switch at residue 53 is indicated). HAV coloured as in a (CrPV and FMDV grey). f, HAV compared with polio virus type 1 (1HXS) in g. The pentamer interface runs horizontally across the centre with the perpendicular 2-fold axis roughly central. Surface drawn for upper pentamer. 2-fold related β-sheets are at A and B. VP1 blue and indigo, VP2 green and lime-green, VP3 red. VP4 omitted for clarity. Upper pentamer chains drawn thicker.

The organisation of the protein chains broadly mirrors other picornaviruses, except for the N-terminus of VP2. At residue 53 there is a flip in the ψ torsion angle of the peptide, sending the first 53 residues of VP2 across and then along the interpentamer boundary to interact strongly with the neighbouring pentamer (forming an extra strand on the VP2 β-barrel from the adjacent pentamer, Fig. 2d-g). The switch is only ~5 Å from the icosahedral 2-fold axis, so that the net effect is to swap the N-terminal structures, in a way reminiscent of domain swaps observed in certain protein structures22. As in those cases, it produces a very similar structure overall, but alters the subunit connectivity so that in HAV adjacent protomers of one pentamer are sewn together via the adjacent pentamer (Fig. 2f,g). This arrangement is unprecedented in picornaviruses, however it occurs in insect picorna-like viruses (e.g. Cricket paralysis virus, CrPV6, Fig. 2d).

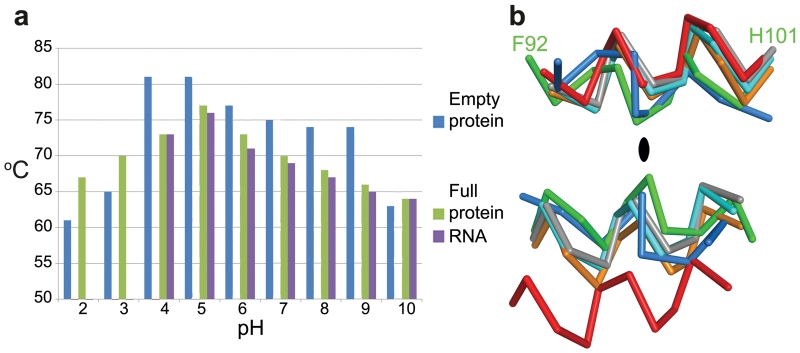

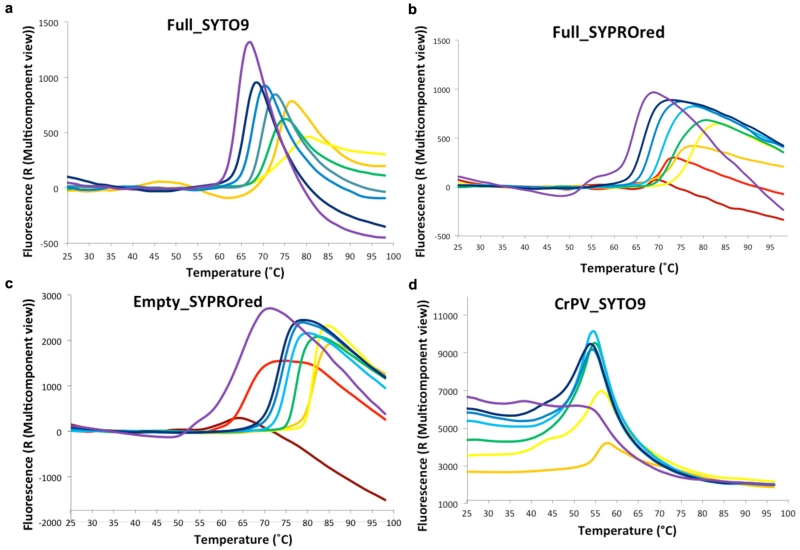

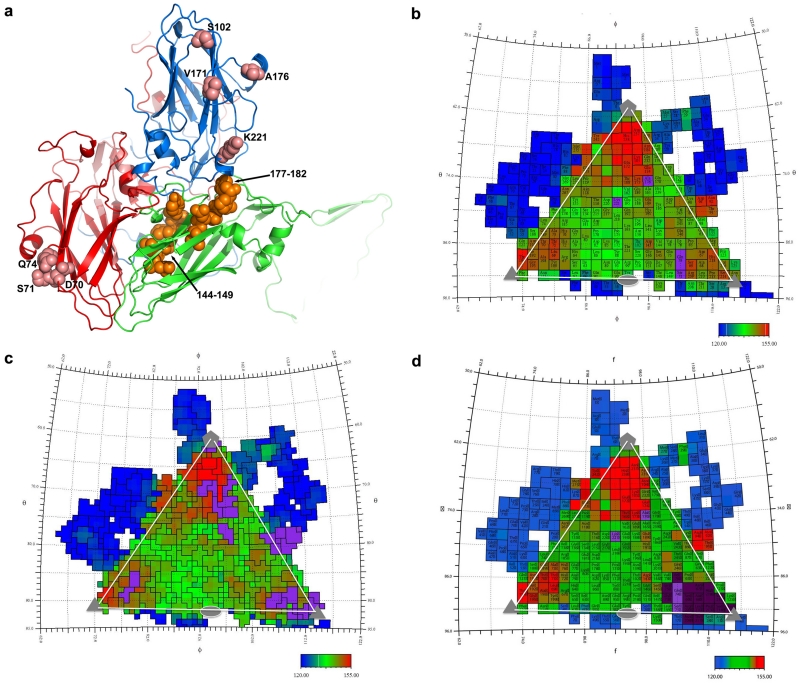

We found that both empty and full particles were extraordinarily robust compared to other picornaviruses (remaining stable at up to 80 °C and at pH’s down to about 223, Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 4). It is established for many picornaviruses that the interface between the twelve pentameric assemblies that comprise the icosahedral capsid determine the particle stability24,25,26. In this context we questioned whether the stability of HAV might be a consequence of the VP2 domain swap at the pentamer interface, and so analysed the stability of CrPV (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Although harbouring the same domain swap CrPV particles showed a stability profile similar to a typical picornavirus. The VP2 switch therefore does not explain the stability, however the interaction region adjacent to the icosahedral 2-fold axes, that separates during the initial stages of enterovirus uncoating17,27, shows tight packing in HAV (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 5). The complementarity is similar to that seen in poliovirus, where instability is likely triggered by pocket factor release. HAV achieves this complementarity by matching small residues and tyrosine side-chains nestled around the 2-fold axis (Extended Data Fig. 5). This may contribute to the stability of the HAV particle, whilst the re-wiring of VP2 may reflect a fundamental difference in the mechanism of genome uncoating in HAV compared to enteroviruses. In contrast the other candidate interface for determining stability, that relating protomers around the icosahedral 5-fold axes, has similar properties to other picornaviruses (Extended Data Fig. 5). We think it unlikely that HAV uses the enterovirus mechanism for genome transfer across the endosomal membrane, via an umbilicus comprising the amphipathic N-terminal helix of VP1, and VP4 membrane pore28,29, although the extremely short VP4 protein has a sequence consistent with the formation of an amphipathic helix. The process of infection comprises two distinct steps, particle entry and genome release. In the first of these HAV may be taken intact into the cell since it is well established that the virus can pass from cell to cell via transcytosis8,9, whereas, the second stage, the release of the RNA genome, remains a puzzle, and a specific host factor (perhaps a protease) may be required for particle disassembly. A recent report suggests that HAV harbours tandem YPX3L motifs (VP2: Y144PHGLL149 and Y177PVWEL182), which are suggested to bind the ALIX component of the ESCRT pathway, allowing the virus to engage the ESCRT complex to facilitate release of enveloped particles via exocytosis2. Surprisingly the residues implicated are buried, making their role unclear unless major conformational rearrangements render them accessible, or if they are accessible on a precursor particle.

Figure 3. Stability.

a, Summary of thermal shift assays for HAV in the pH range from 2 to 10. Purple and green bars represent RNA release and protein-melting temperatures respectively for full HAV, blue bars show protein melting for the empty particle. RNA release is not detected at low pH due to quenching of the SYTO9 dye. Extended Data Fig. 4 shows raw fluorescence traces. b, The separation of VP2 α-helices at the icosahedral 2-fold of HAV (green, 3.8Å), CrPV (blue, 5.3Å), EV71 (cyan, 7.3Å), polio (grey, 7.6Å ), FMDV (orange, 8.2Å) and 80S-like EV71 (red, 12.2Å).

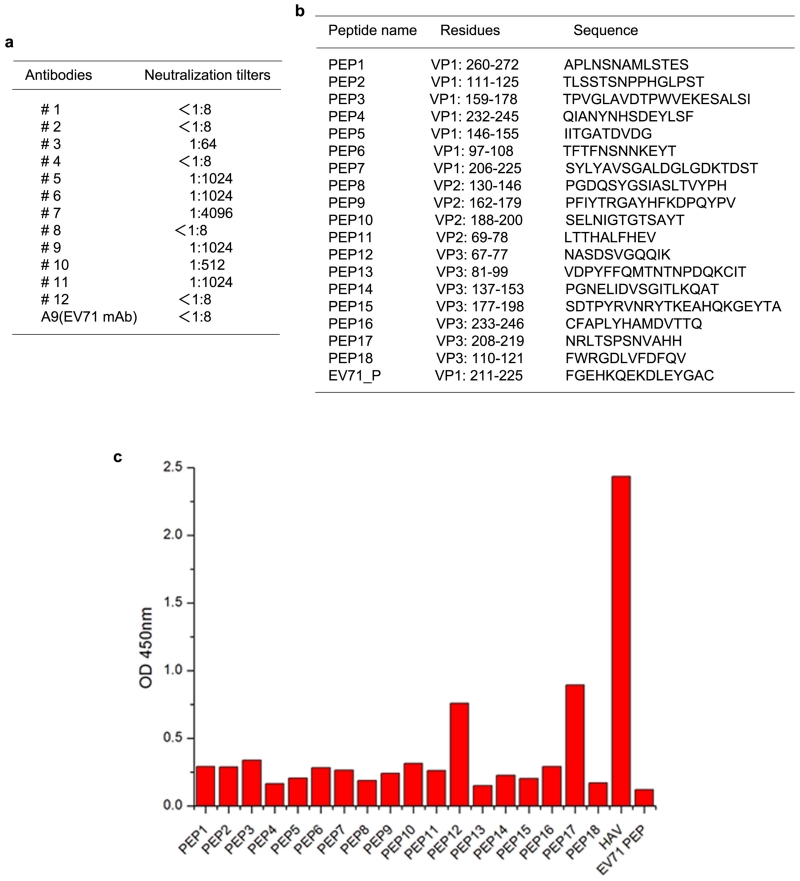

The antigenicity of HAV is incompletely characterised, with residues S102, V171, A176 and K221 of VP1 and D70, S71, Q74 and 102-121 of VP3 implicated in neutralizing epitopes4. All except K221 of VP1 are proposed to form part of a single site, however they are separated by 40-50 Å on the particle surface (Extended Data Fig. 6). To extend our knowledge, twelve monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against HAV particles were generated (Extended Data Fig. 7), one of which, mAb #11, combined excellent neutralizing titer with VP3 western blot activity. Based on the particle structure a series of peptides covering all exposed virus surface regions, were synthesized and tested against mAb #11. VP3 residues 67-77 and 208-219 (Extended Data Fig. 7) reacted mildly. The proximity of these regions on the surface of VP3 (Extended Data Fig. 6) suggests both may contribute to a conformational epitope, an augmented version of that previously identified by Ping et al.4. To identify further antigenic sites on HAV we applied structure-based predictive methodology5, which supports the above findings and suggests that VP2 residues 71 and 198, and VP3 residues 89-96 may comprise additional epitopes (Extended Data Fig. 6).

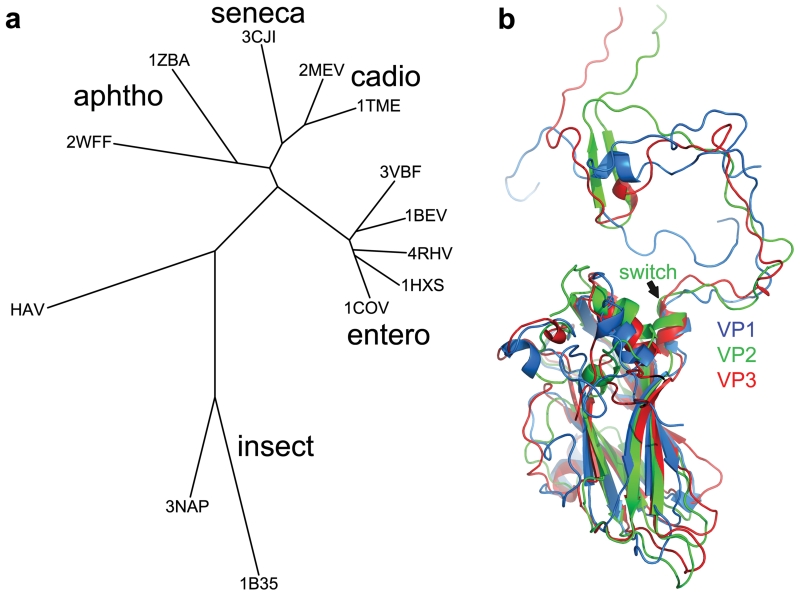

HAV possesses subtle but profound structural differences compared to previously characterized picornaviruses. A structure-based phylogeny (Fig. 4a) suggests that HAV links classical picornaviruses and the insect picorna-like viruses. Furthermore the N-terminal domain swap renders VP2 more similar to the homologous VP1 and VP3 proteins (Fig. 4b), supporting the notion that HAV retains structural and functional features characteristic of primordial picornaviruses, which were akin to present day insect picorna-like viruses, and that the subsequent acquisition of efficient mechanisms of cell entry allowed the explosion in diversity that characterizes present-day mammalian picornaviruses.

Figure 4. Phylogeny.

a, Structure-based phylogenetic tree30 of representative picornaviruses and cripaviruses, 3VBF (EV71), 1BEV (bovine enterovirus), 4HRV (human rhinovirus14), 1HXS (poliovirus type1), 1COV (coxsackievirus B3), 1TME (Theilers virus), 3MEV (mengo virus), 3CJI (Seneca valley virus), 1ZBA (FMDV A10), 2WFF (equine rhinitis A virus), 3NAP (triatoma virus) and 1B35 (CrPV). Evolutionary distance is derived from the number of unmatched residues and the deviation in matched residues. Residues corresponding to the HAV VP2 switch region (1-53) are excluded (including them does not affect the result). b, Superimposition of HAV VP1 (blue), VP2 (green) and VP3 (red), note the similar N-terminal extensions.

Methods

Particle production and purification

HAV virus genotype TZ84 was used to infect 2BS cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2 at 33-34 °C. Cells were harvested 4 weeks post infection, lysed by treatment with ice-cold 1% sodium deoxycholate in PBS buffer (pH 7.2) and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm filter, concentrated with a 100kD cutoff concentrator and washed with PBS buffer repeatedly. Virus was inactivated by incubation with formaldehyde (1:2000 dilution) at 4 °C for 7 days, followed by polyethylene glycol 6000 precipitation, chloroform extraction, differential ultracentrifugation and gel filtration. Crude HAV concentrate (1mg in PBS buffer pH 7.4) was loaded onto a 15-45% (W/V) sucrose density gradient and centrifuged at 29000 rpm for 3.5 h in an SW41 rotor at 4 °C. Two sets of fractions were collected and dialyzed against PBS buffer (Extended Data Fig. 1a), one contained empty particles (containing no RNA) and the other virions. The two types of viral particles were further purified by 10-40% (W/V) sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation at 29000 rpm for 3 h in an SW41 rotor at 4 °C. The main bands were collected and dialyzed against PBS buffer.

Biochemical, Biophysical and EM Analysis

SDS-PAGE for protein analysis used a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Extended Data Fig. 1b). The sedimentation coefficients for the two types of particles were determined using a Beckman XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge at 4°C (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). These results confirmed the two types of HAV particles as full virions containing proteins VP1-4 and RNA and possessing a sedimentation coefficient of 144S and empty particles containing VP0, 1 and 3 with no RNA and a sedimentation coefficient of 82S.

Transmission Electron microscope

Inactivated purified HAV viral particles were deposited onto a carbon-coated grid for 1 min. Excess sample was removed with filter paper, the grid washed twice with double distilled water and the sample immediately negatively stained for 30s with 2% phosphotungstic acid (adjusted to pH 7.0 with 1 M KOH). Excess stain was removed, and the sample air-dried and transferred to an FEI Tecnai 20 transmission electron microscope for visualization (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f)

Thermofluor assay

Thermofluor experiments were performed with an MX3005p RT-PCR instrument (Agilent/Stratagene). SYTO9 and SYPROred (both Invitrogen) were used as fluorescent probes to detect the presence of single stranded RNA and exposed hydrophobic regions of proteins respectively23. 50 μL reactions were set up in a thin-walled PCR plate (Agilent), containing 0.5-1.0 μg of either virus or empty particles, 5 μM SYTO9 and 3× SYPROred in pH ranging from 2 to 10 buffer solutions and ramped from 25-99 °C with fluorescence recorded in triplicate at 1°C intervals. The RNA release (Tr) and melting temperature (Tm) were taken as the minimums of the negative first derivative of the RNA exposure and protein denaturation curves, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Crystallization and Data Collection

Full and empty particles were concentrated to 1.5 and 3 mg/ml respectively prior to crystallization in Greiner CrystalQuick™X plates using a version of the previously described nano-litre vapour diffusion procedure31 with 30% MPD and 0.5 M ammonium sulphate as precipitants and 0.1 M HEPES-Na buffer at pH7.5. Crystals (rectangular plates of dimensions ~100×100×5 μM) were cryo-protected using solutions containing up to 50% MPD and 20% glycerol depending on the crystal age. Data were collected from frozen crystals (100K) on beamlines I03 and I24 at Diamond Light Source UK. Diffraction images of 0.1° rotation were recorded on a Pilatus6M detector using beam size from 0.02×0.02 mm2 to 0.08×0.06 mm2, commensurate with crystal size. Using 1.0 s exposure time and 100% beam transmission, typically 50 useful images could be collected from one position of a crystal. For some larger crystals, data could be collected from 2 positions. A total of some 200 crystals of both full and empty particles were frozen and tested. 17 empty particle crystals diffracted and gave a data set to 3.5Å resolution with 68.0% completeness; 32 full virus crystals resulted in a data set to 3.0Å resolution with 44.4% completeness. Although the data suffered from the large mosaic spread of the crystals, the minimal divergence of the X-ray beam on I03 ameliorated the problem.

Structure determination

Data were analysed using HKL200032. The mosaicity differed for the full and empty particle crystals ranging from 0.35° to 0.85°. The data were inevitably very weak with average I/σI of 1.4 for the full particle data set and 3.0 for the empty particle data sets. The structures of both particles were determined by molecular replacement. The space group for the empty particle was P21212 with unit cell dimensions: a=366.1 Å, b=442.9 Å and c=289.0 Å (30 protomers in a crystallographic asymmetric unit). For the full virus, the unit cell dimensions are a=291.5 Å, b=423.3 Å, c=314.8 Å and β=100.2° space group P21 with a full particle in asymmetric unit. Phasing used molecular replacement with an FMDV model (Cα’s of a pentamer, PDB code: 1FMD) followed by non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging and refinement using strict NCS constraints33. The full virus was centred at (194.1, 106.1, 85.6) and the empty particle at (0, 221.5, 6.0). For each space group the content of the crystallographic asymmetric unit was subjected to rigid-body refinement, followed by cyclic positional, simulated annealing and B-factor refinement using strict NCS constraints with CNS33. Maps were averaged used GAP (DIS, J Grimes & J Diprose, unpublished) and models were rebuilt with COOT34. Refinement of the full particle structure stuck at an R-factor of 31.8%, probably attributable to imperfect isomorphism of the constituent crystals and to the extreme weakness of the data. For statistics, see Extended Data Table 1. Structural comparisons used SHP35. Unless otherwise noted structural figures were prepared with PyMOL36.

Production of monoclonal antibody and neutralization assay

Groups of 15 adult (4 weeks old) female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 10 μg inactivated HAV virus. Two booster doses were given at 2 weekly intervals. Two weeks after the last immunization, blood samples were obtained from the tail and tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using purified HAV virus as antigen. Classical protocols for production of monoclonal antibody were followed (continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity). For the neutralization assay, purified monoclonal antibodies at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml were initially diluted 8-fold as stocks, and then serially diluted 2-fold with DMEM containing 2% FBS. 100 μl of 2-fold antibody dilutions were mixed with 100 μl of HAV virus containing 100 TCID50 for 1 h at 37 °C, and then added to monolayers of 2BS cells in cell culture flasks (T25 CM²), meanwhile, maintaining medium was provided as well. Each dilution was replicated 3 times along with one control that contained no serum dilution. After 21 days of growth at 33 °C, the medium was removed and the cells washed three times using PBS buffer, 1ml of Trypsin/EDTA was added and the flask left for 3 min at 37 °C. The suspended cells were freeze-thawed 5 times to collect the virus. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to determine neutralizing titer. The titers were read as the highest dilution that gave complete protection.

Peptide-ELISA Assay

Synthetic peptides spanning the entire exposed region of HAV VP1, VP2 and VP3 capsid proteins, were synthesized by Scilight-Peptide Company (Beijing, P.R.China). The reactivity of synthetic peptides with purified HAV neutralizing mAb was measured by ELISA. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl/well of individual peptide (10 μg/ml in PBS buffer) at 4 °C overnight. An unrelated EV71 peptide was used as a negative control and inactivated HAV as a positive control. The wells were then incubated sequentially with 100 μl/well of PBST plus 5% skimmed milk powder at 37 °C for 1 h, and 100 μl/well of HAV neutralizing mAbs at the indicated dilutions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG diluted (1:5000) in PBST plus 1% milk powder was used as secondary antibody at 37 °C for 1 h. Five washes with PBST were carried out between incubation steps. For color development, 100 μl/well of TMB mixture was added and incubated for 10 min, followed by addition of 50 μl/well of 1M H3PO4 to stop the reaction. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a 96-well plate reader.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. HAV purification and characterization.

a, Zonal ultracentrifugation of a 15 to 45% (w/v) sucrose density gradient at 103614 g for 3.5 h was used to purify HAV, as described in Methods. Two predominant particle types were separated; one was located at ~27% sucrose, the other at ~32% sucrose. The absorbance ratios (λ260/λ280) were 0.76 for the top band and 1.66 for the bottom band indicating that the former contained mainly empty particles without the RNA genome and the latter mainly full particles with the RNA genome. The top band was much broader than the bottom one. Three and two fractions were collected around the top and the bottom bands, respectively, for further purification. b, SDS-PAGE for protein composition analysis using A NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen). Each lane was loaded with 5-10 μg sample (lane 1, full particles; lane 2, empty particles; lane 3, markers). The calculated molecular weights of VP0, VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4 were 27.26 kD, 30.73 kD, 24.80 kD, 27.86 kD and 2.50 kD, respectively. The results appear to show incomplete cleavage of VP0 in the full particles and no VP0 cleavage in the empty particles. c,d, Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed on a Beckman XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge at 20 °C. Samples were loaded into a conventional double-sector quartz cell and mounted in a Beckman four-hole An-60 Ti rotor. Data were collected at 15,000 rpm at a wavelength of 287 nm. Interference sedimentation coefficient distributions were calculated from the sedimentation velocity data using SEDFIT37. The full particle has a sedimentation coefficient of 144S and the empty particle 82S. e,f, Negative stain electron microscopy of HAV particles. Particles from the top band in panel a, shown in panel f, suggest that light sedimentation fractions were mainly composed of empty particles. Note that some particles appear to have external features. Panel e shows the heavy particles, which appear to contain viral RNA.

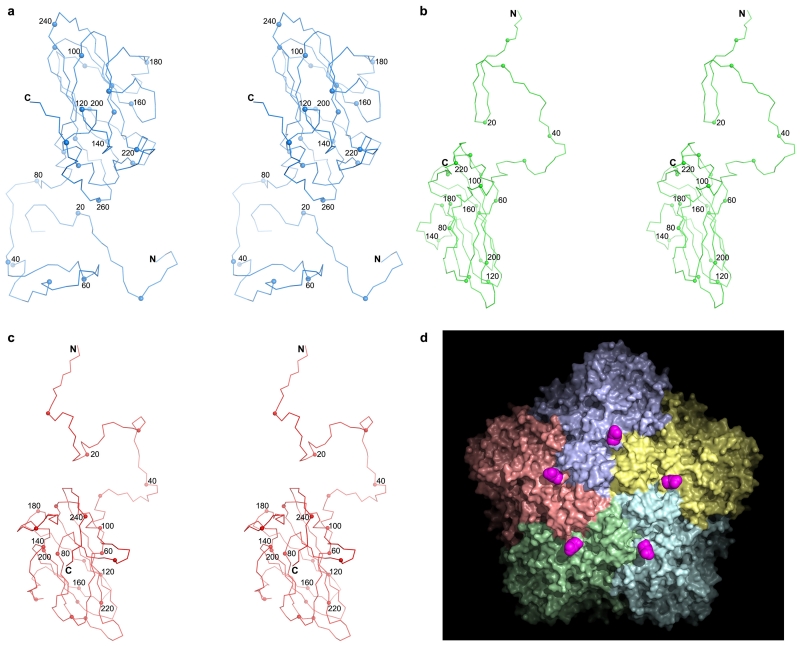

Extended Data Figure 2. HAV capsid protein structure.

a,c, Stereo diagrams showing the structures of the capsid proteins VP1, VP2 and VP3, respectively. The Cα backbone is shown as a thin line, the N and C termini are labeled, every 10th residue is marked with a small sphere and every 20th is numbered. d, VP1 is initially produced with an 8 kD C-terminal extension (known as PX) unique to HAV among picornaviruses. PX is cleaved from the full particle by an unknown host protease. According to the data shown in Extended Data Figure 1 and the electron density maps, the particles we have analysed do not contain PX, but if it were present we would expect its course to start at the purple positions (C-termini of VP1) on the surface of the virus.

Extended Data Figure 3. Antigenicity of Full and Empty Particles.

The reactivity of HAV full and empty particles against a panel of 6 purified HAV neutralizing mAbs was measured by ELISA. The bar charts represent the average OD450 reading for the six mAbs at each dilution with the standard deviation shown as an error bar.

Extended Data Figure 4. PaSTRy assays.

To characterize the stability of HAV full and empty particles compared to CrPv across the pH range from 2.0 to 10.0 differential scanning fluorimetry assays were performed with dyes SYTO9 (to detect RNA exposure) and SYPRO RED (to detect protein melting)23. a, The raw fluorescence traces of HAV full particles incubated with SYTO9. b, The raw fluorescence traces of HAV full particles incubated with SYPRO red. c, The raw fluorescence traces of HAV empty particles incubated with SYPRO red. d, The raw fluorescence traces of CrPV full particles incubated with SYTO9 across the same pH range. The colour scheme is dark red (pH 2.0), red (pH 3.0), orange (pH 4.0), yellow (pH 5.0), green (pH 6.0), sky blue (pH 7.0), blue (pH 8.0), dark blue (pH 9.0) and purple (pH 10.0). Since the SYTO9 dye didn’t function well below pH 4.0 the fluorescence traces for pH 2.0 and pH 3.0 are omitted. These results indicate that HAV full virions are most stable at pH 5.0 and RNA genome release occurs at about 76 °C and protein melting at 77 °C, i.e. there is no notable transition between RNA release and particle loss. HAV empty particles show a similar trend but appear to withstand temperatures up to 81°C in low pH buffer. In contrast CrPV is most stable at pH 4.0 and RNA genome release occurs at about 54 °C.

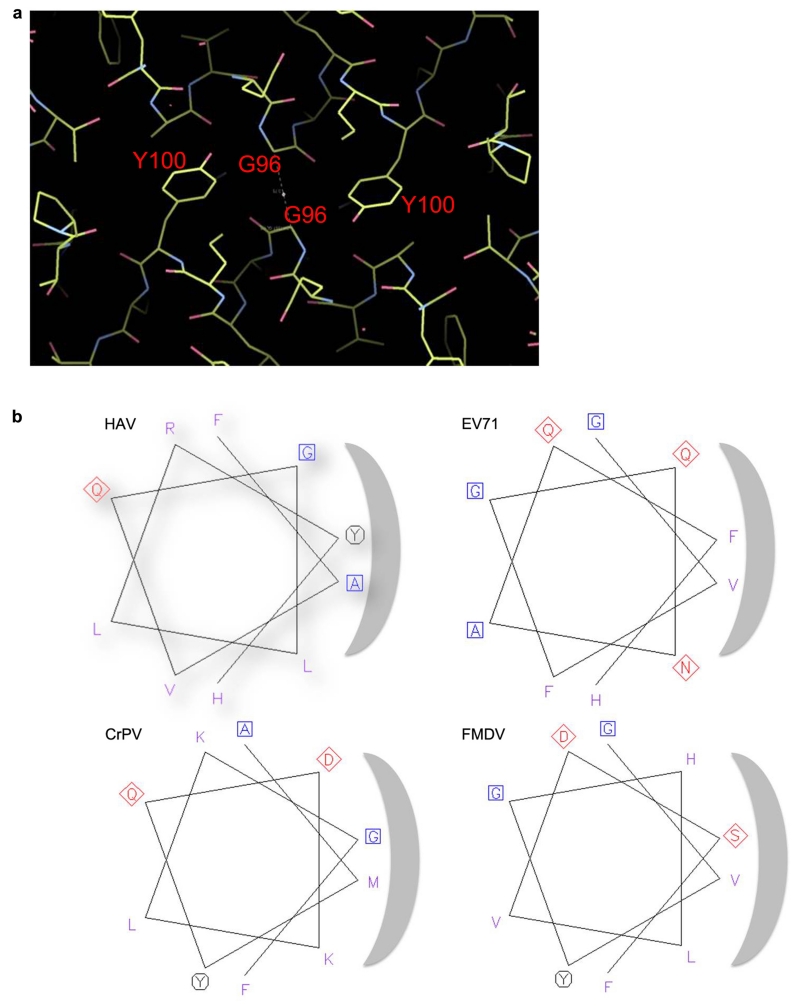

Extended Data Figure 5. Interactions between α1 helices of VP2 at the icosahedral 2-fold.

a, The close-packing of the two helices is shown in particular the packing of Tyr 100 against the adjacent helix. The contact area between these helices and the surface complementarity38 suggests a well fitting interface for HAV (contact area 83 Å2, surface complimentarity 0.755, EV71: 111/0.550, Polio-1: 124/0.785, CrPV: 72/0.707, FMDV: 50/0.593). The interface between protomers forming the pentameric units is similar for all these viruses (HAV: 4267 Å2, Polio-1: 4369 Å2, CrPV: 4647 Å2, EV71: 4131 Å2, FMDV-A22: 3432 Å2). b, Helical wheel diagrams for helix α1 of several picornaviruses showing the unusually small side chains at the helix interface in HAV.

Extended Data Figure 6. Antigenicity and YPX3L ALIX-interacting motifs.

a, Previously indicated antigenic sites of HAV are mapped onto the structure (pink spheres). Late domain YPX3L motifs are shown as orange spheres. b,d, Surface maps of HAV generated using RIVEM39 such that area for each residue as drawn corresponds to its accessible area and the coloration is according to the radius from the virus centre (Blue deepest, red most exposed). On these the antigenic sites of HAV are depicted in purple. b, Previously reported antigenic sites; c, predicted sites5; d, new sites determined by peptide mapping (indigo) together with previously identified sites (purple).

Extended Data Figure 7. mAb neutralization assays and peptide epitope mapping.

a, In vitro neutralization assays of monoclonal antibodies against HAV (TZ84). b, Peptides used for epitope mapping. c, Reactivity of the neutralizing mAb #11 against synthetic peptides measured by peptide-ELISA.

Extended Data Table 1.

Data collection, phasing and refinement statistics

Note that the R-free is of limited significance owing to the considerable non-crystallographic symmetry, 30-fold and 60-fold for the empty and full particles respectively.

| Empty particle | Full particle | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Beam line | Diamond I03 and I24 | |

| particle | empty | full |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 |

| Space group | P21212 | P21 |

| No. of crystals (positions) | 17(29) | 32(36) |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | a=366.1, b=442.9, c=289.0 | a=291.5, b=423.3, c=314.8, β=100.2° |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–3.50 (3.56–3.50) | 50.0–3.00 (3.05–3.00) |

| Unique reflections | 404893(2925) | 654559(6711) |

| Rmerge | 0.363(---) | 0.410(0.933) |

| I / σI | 3.0(0.3) | 1.4(0.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 68.0(9.9) | 44.4(9.1) |

| Redundancy | 2.5(1.1) | 1.9(1.1) |

|

| ||

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0 – 3.50 | 50.0 – 3.00 |

| No. reflections | 392844/3880 | 643384/6633 |

| Rwork /Rfree* | 0.264/0.263 | 0.318/0.321 |

| No. atoms | 5358 | 5742 |

| Mean B-factors (Å2) | 179 | 37 |

| r.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.0 | 1.4 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Major Project of Infectious Disease, the Ministry of Science and Technology 973 Project (grant no. 2014CB542800), National Science Foundation Grant 81330036 and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDB08020200. DIS & EEF are supported by the UK Medical Research Council (grant No. G1000099) and JR by the Wellcome Trust. This work is a contribution from the Instruct Centre, Oxford. Administrative support was provided by the Wellcome Trust (075491/Z/04). We thank Jack Johnson and Andrew Routh for supplying CrPV, and Stan Lemon and Kevin McKnight for discussions. The coordinates and structure factors for the full and empty particles have been deposited with the RCSB under accession codes: 4QPI, 4QPG, respectively.

References

- 1.WHO ( Fact sheet N°328 ).Hepatitis A. 2013

- 2.Feng Z, et al. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature. 2013;496:367–71. doi: 10.1038/nature12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegl G, Weitz M, Kronauer G. Stability of hepatitis A virus. Intervirology. 1984;22:218–26. doi: 10.1159/000149554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ping LH, Lemon SM. Antigenic structure of human hepatitis A virus defined by analysis of escape mutants selected against murine monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1992;66:2208–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2208-2216.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borley DW, et al. Evaluation and use of in-silico structure-based epitope prediction with foot-and-mouth disease virus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tate J, et al. The crystal structure of cricket paralysis virus: the first view of a new virus family. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:765–74. doi: 10.1038/11543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Squires G, et al. Structure of the Triatoma virus capsid. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1026–37. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913004617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dotzauer A, Brenner M, Gebhardt U, Vallbracht A. IgA-coated particles of Hepatitis A virus are translocalized antivectorially from the apical to the basolateral site of polarized epithelial cells via the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2747–51. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dotzauer A, et al. Hepatitis A virus-specific immunoglobulin A mediates infection of hepatocytes with hepatitis A virus via the asialoglycoprotein receptor. J Virol. 2000;74:10950–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.10950-10957.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deinhardt F. Prevention of viral hepatitis A: past, present and future. Vaccine. 1992;10(Suppl 1):S10–4. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90532-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemon SM, Binn LN. Antigenic relatedness of two strains of hepatitis A virus determined by cross-neutralization. Infect Immun. 1983;42:418–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.418-420.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graff J, et al. Hepatitis A virus capsid protein VP1 has a heterogeneous C terminus. J Virol. 1999;73:6015–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6015-6023.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesar M, Jia XY, Summers DF, Ehrenfeld E. Analysis of a potential myristoylation site in hepatitis A virus capsid protein VP4. Virology. 1993;194:616–26. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin A, Lemon SM. Hepatitis A virus: from discovery to vaccines. Hepatology. 2006;43:S164–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.21052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan G, et al. Identification of a surface glycoprotein on African green monkey kidney cells as a receptor for hepatitis A virus. EMBO J. 1996;15:4282–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop NE, Anderson DA. RNA-dependent cleavage of VP0 capsid protein in provirions of hepatitis A virus. Virology. 1993;197:616–23. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, et al. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:424–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossmann MG, et al. Structure of a human common cold virus and functional relationship to other picornaviruses. Nature. 1985;317:145–53. doi: 10.1038/317145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegl G, Frosner GG, Gauss-Muller V, Tratschin JD, Deinhardt F. The physicochemical properties of infectious hepatitis A virions. J Gen Virol. 1981;57:331–41. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-57-2-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Colibus L, et al. More-powerful virus inhibitors from structure-based analysis of HEV71 capsid-binding molecules. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:282–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acharya R, et al. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 A resolution. Nature. 1989;337:709–16. doi: 10.1038/337709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: as domains continue to swap. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1285–99. doi: 10.1110/ps.0201402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter TS, et al. A plate-based high-throughput assay for virus stability and vaccine formulation. J Virol Methods. 2012;185:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porta C, et al. Rational engineering of recombinant picornavirus capsids to produce safe, protective vaccine antigen. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003255. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filman DJ, et al. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 1989;8:1567–79. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warwicker J. Model for the differential stabilities of rhinovirus and poliovirus to mild acidic pH, based on electrostatics calculations. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:247–57. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garriga D, et al. Insights into minor group rhinovirus uncoating: the X-ray structure of the HRV2 empty capsid. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren J, et al. Picornavirus uncoating intermediate captured in atomic detail. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1929. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butan C, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. Cryo-electron microscopy reconstruction shows poliovirus 135S particles poised for membrane interaction and RNA release. J Virol. 2014;88:1758–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01949-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riffel N, et al. Atomic resolution structure of Moloney murine leukemia virus matrix protein and its relationship to other retroviral matrix proteins. Structure. 2002;10:1627–36. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ONLINE ONLY REFERENCE LIST

- 31.Walter TS, et al. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:651–7. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution--from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:859–66. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuart DI, Levine M, Muirhead H, Stammers DK. Crystal structure of cat muscle pyruvate kinase at a resolution of 2.6 A. J Mol Biol. 1979;134:109–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.PyMOL . The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4. Schrödinger, LLC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–19. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape complementarity at protein/protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:946–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman MS, Rossmann MG. Comparison of surface properties of picornaviruses: strategies for hiding the receptor site from immune surveillance. Virology. 1993;195:745–56. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.