Abstract

Objective

To estimate global surgical volume in 2012 and compare it with estimates from 2004.

Methods

For the 194 Member States of the World Health Organization, we searched PubMed for studies and contacted key informants for reports on surgical volumes between 2005 and 2012. We obtained data on population and total health expenditure per capita for 2012 and categorized Member States as very-low, low, middle and high expenditure. Data on caesarean delivery were obtained from validated statistical reports. For Member States without recorded surgical data, we estimated volumes by multiple imputation using data on total health expenditure. We estimated caesarean deliveries as a proportion of all surgery.

Findings

We identified 66 Member States reporting surgical data. We estimated that 312.9 million operations (95% confidence interval, CI: 266.2–359.5) took place in 2012, an increase from the 2004 estimate of 226.4 million operations. Only 6.3% (95% CI: 1.7–22.9) and 23.1% (95% CI: 14.8–36.7) of operations took place in very-low- and low-expenditure Member States representing 36.8% (2573 million people) and 34.2% (2393 million people) of the global population of 7001 million people, respectively. Caesarean deliveries comprised 29.6% (5.8/19.6 million operations; 95% CI: 9.7–91.7) of the total surgical volume in very-low-expenditure Member States, but only 2.7% (5.1/187.0 million operations; 95% CI: 2.2–3.4) in high-expenditure Member States.

Conclusion

Surgical volume is large and growing, with caesarean delivery comprising nearly a third of operations in most resource-poor settings. Nonetheless, there remains disparity in the provision of surgical services globally.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer le volume mondial d'interventions chirurgicales pratiquées en 2012 et le comparer aux estimations de 2004.

Méthodes

Nous avons recherché sur PubMed des études concernant les 194 États membres de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé et avons contacté des informateurs clés afin de nous procurer les rapports sur les volumes d'interventions chirurgicales entre 2005 et 2012. Nous avons obtenu des données sur la population et les dépenses totales de santé par habitant pour 2012 et avons caractérisé les États membres selon que ces dépenses étaient très faibles, faibles, moyennes ou élevées. Des rapports statistiques validés nous ont fourni des données sur les césariennes. Pour les États membres qui ne disposaient pas de données archivées sur les interventions chirurgicales, nous avons estimé les volumes au moyen de plusieurs imputations à partir des données sur les dépenses totales de santé. Nous avons estimé le nombre de césariennes en fonction du nombre total d'interventions.

Résultats

Nous avons identifié 66 États membres communiquant des données sur les interventions chirurgicales. Nous avons estimé que 312,9 millions d'opérations (intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC 95%: 266,2–359,5) avaient eu lieu en 2012, soit une augmentation par rapport à l'estimation 2004 de 226,4 millions d'opérations. Seules 6,3% (IC 95%: 1,7–22,9) et 23,1% (IC 95%: 14,8–36,7) des opérations ont eu lieu dans des États membres aux dépenses très faibles et faibles, ce qui représente respectivement 36,8% (2573 millions de personnes) et 34,2% (2393 millions de personnes) de la population mondiale de 7001 millions de personnes. Les césariennes représentaient 29,6% (5,8/19,6 millions d'opérations; IC 95%: 9,7–91,7) du volume total d'interventions chirurgicales pratiquées dans les États membres aux dépenses très faibles, mais seulement 2,7% (5,1/187,0 millions d'opérations; IC 95%: 2,2–3,4) dans les États membres aux dépenses élevées.

Conclusion

Le volume d'interventions chirurgicales est important et ne cesse d'augmenter. Les césariennes représentent près d'un tiers des opérations dans les pays aux plus faibles ressources. Néanmoins, la fourniture de services chirurgicaux dans le monde continue de présenter des disparités.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar el volumen global de intervenciones quirúrgicas en 2012 y compararlo con las estimaciones de 2004.

Métodos

Se realizaron búsquedas de estudios en PubMed y se contactó a informantes clave para obtener información sobre el volumen de intervenciones quirúrgicas entre 2005 y 2012 para los 194 Estados Miembros de la Organización Mundial de la Salud. Se obtuvieron datos sobre la población y el gasto total en salud per cápita en 2012 y se categorizó a los Estados Miembros por gasto muy bajo, bajo, medio y elevado. Se obtuvieron datos acerca del número de cesáreas de informes estadísticos validados. Para los Estados Miembros sin datos quirúrgicos registrados, se estimaron los volúmenes por varias asignaciones utilizando datos sobre el gasto total en salud. Se estimó el numero de cesareas como un porcentaje del total de las intervenciones quirúrgicas.

Resultados

Se identificaron 66 Estados Miembros que registran datos quirúrgicos. Se estimó que en 2012 se realizaron 312,9 millones de operaciones (intervalo de confianza del 95%, IC del 95%: 266,2–359,5), lo que significa un aumento de la estimación de 226,4 millones de operaciones de 2004. Únicamente un 6,3% (IC del 95%: 1,7–22,9) y un 23,1% (IC del 95%: 14,8–36,7) de las operaciones fueron realizadas en Estados Miembros de gasto muy bajo y bajo, lo que representa el 36,8% (2 573 millones de personas) y el 34,2% (2 393 millones de personas) de la población mundial de 7 001 millones de personas, respectivamente. Las cesáreas abarcaron el 29,6% (5,8/19,6 millones de operaciones; IC del 95%: 9,7–91,7) del total del volumen de intervenciones quirúrgicas en Estados Miembros con un gasto muy bajo, pero únicamente el 2,7% (5,1/187,0 millones de operaciones; IC del 95%: 2,2–3,4) en Estados Miembros con un gasto elevado.

Conclusión

El volumen de intervenciones quirúrgicas es cada vez mayor, y las cesáreas abarcan casi un tercio de las operaciones en los lugares con menos recursos. No obstante, sigue habiendo una diferencia en el suministro de servicios quirúrgicos a nivel global.

ملخص

الغرض تقدير عدد العمليات الجراحية التي تم إجراؤها في عام 2012 على مستوى العالم ومقارنته بالتقديرات التي تم التوصل إليها في عام 2004.

الطريقة بحثنا في محرك البحث PubMed عن بعض الدراسات واتصلنا بالمبلّغين الرئيسيين بشأن التقارير المتعلقة بأعداد العمليات الجراحية التي تم إجراؤها في الفترة بين عامي 2005 و2012، وذلك فيما يتعلق بالدول الأعضاء في منظمة الصحة العالمية البالغ عددها 194 دولة. وقد حصلنا على بيانات بشأن السكان وإجمالي النفقات الصحية للفرد الواحد لعام 2012 وصنفنا الدول الأعضاء في شرائح النفقات الشديدة الانخفاض، والنفقات المنخفضة، والنفقات المتوسطة، والنفقات المرتفعة. وتم الحصول على البيانات المتعلقة بالولادة القيصرية من التقارير الإحصائية الموثقة. وفيما يتعلق بالدول الأعضاء التي لا تتوفر بها بيانات مسجلة عن العمليات الجراحية، فقد أجرينا تقديرًا للأعداد بالاستعانة بطريقة حساب القيم التعويضية المتعددة باستخدام البيانات المتعلقة بالنفقات الصحية. واتخذنا الولادات القيصرية كنسبة لتقدير جميع العمليات الجراحية.

النتائج حددنا 66 دولة من بين الدول الأعضاء يتوفر بها تقارير ببيانات العمليات الجراحية. وحسب تقديرنا تم إجراء 312.9 مليون عملية جراحية (بنسبة أرجحية مقدارها 95%: 266.2 – 359.5) في عام 2012، بزيادة عن الأعداد المقدَّرة في عام 2004 تبلغ 226.4 مليون عملية جراحية. بنسبة 6.3% فقط (بنسبة أرجحية مقدارها 95%: 1.7 – 22.9) و23.1% (بنسبة أرجحية مقدارها 95%: 14.8 – 36.7) من العمليات الجراحية التي تم إجراؤها في الدول الأعضاء من شريحتي النفقات شديدة الانخفاض والنفقات المنخفضة بما يمثل 36.8% (2573 مليون شخص) و34.2% (2393 مليون شخص) من التعداد العالمي للسكان الذي يبلغ 7001 مليون نسمة، على التوالي. وشكلت الولادات القيصرية 29.6% (5.8/19.6 مليون عملية جراحية؛ بنسبة أرجحية مقدارها 95%: 9.7 – 61.7) من إجمالي عدد العمليات الجراحية في الدول الأعضاء من شريحة النفقات الشديدة الانخفاض، ولكن بلغت النسبة 2.7% فقط (5.1/187.0 مليون عملية جراحية؛ بنسبة أرجحية مقدارها 95%: 2.2 – 3.4) في الدول الأعضاء من شريحة النفقات المرتفعة.

الاستنتاج إن عدد العمليات الجراحية كبير ومتزايد، وتمثل الولادة القيصرية ما يقرب من ثلث العمليات الجراحية في معظم المواقع التي تفتقر إلى الموارد. وبالرغم من ذلك، يظل الفارق في توفير الخدمات الجراحية قائمًا على المستوى العالمي.

摘要

目的

旨在评估 2012 年全球外科手术总量,并将其与 2004 年数据进行比较。

方法

对于世界卫生组织的 194 个成员国,我们搜索 PubMed 进行调查,并联系关键受访者,获得 2005 年至 2012 年间外科手术总量的报告。我们获得 2012 年人口数据及人均卫生开支总额的数据,并将成员国分为开支非常低、低、中等及高这四类。利用经过验证的统计报告获知剖腹产手术的数据。对于没有外科手术记录数据的成员国,我们通过使用卫生开支总额数据进行的多次估算,推算出外科手术总量。我们也将剖腹产手术作为一种外科手术进行评估。

结果

我们确定 66 个成员国报告了外科手术数据。我们估计 2012 年外科手术总量为 312,900,000(95% 置信区间,95% CI:266.2–359.5),相较于 2004 年,增长 226,400,000 次手术。其中,仅 6.3% (95% CI:1.7–22.9) 和 23.1% (95% CI:外科手术发生于开支非常低和低的成员国,而在全球 7,001,000,000 人口中,其分别占 36.8%(2,573,000,000 人口)和 34.2%(2,393,000,000 人口)。在开支非常低的成员国,剖腹产手术量在外科手术总量中占 29.6%(5,800,000/19,600,000 外科手术量;95% CI:9.7–91.7),但在开支高的成员国,仅占 2.7%(5,100,000/187,000,000 外科手术量;95% CI:2.2–3.4)。

结论

外科手术数量很大,且不断增长,其中在资源匮乏地区,剖腹产手术约占外科手术总量的三分之一。不过,外科手术服务在全球范围内仍有所不同。

Резюме

Цель

Подсчитать общемировой объем хирургических операций в 2012 г. и сравнить его с результатами оценки, проведенной в 2004 г.

Методы

Для получения результатов для 194 государств-членов Всемирной организации здравоохранения осуществлялся поиск по базе данных PubMed на предмет исследований, а также были запрошены отчеты по объему хирургических операций у ключевых информаторов за период 2005–2012 гг. Были получены данные о численности населения и общих расходах на здравоохранение на душу населения для 2012 г., и государства-члены были разделены на группы: с очень низким уровнем расходов, с низким уровнем расходов, со средним уровнем расходов и с высоким уровнем расходов. Сведения о количестве кесаревых сечений были получены из утвержденных статистических отчетов. Для получения результатов для государств-членов, в которых данные по хирургии не фиксировались, объемы были подсчитаны с помощью нескольких условных значений на основе данных об общих расходах на здравоохранение. Была подсчитана доля кесаревых сечений от всех хирургических операций.

Результаты

66 государств-членов сообщили данные о хирургических операциях. Согласно подсчетам 312,9 млн операций (доверительный интервал 95%, 95% ДИ: 266,2–359,5) было проведено в 2012 г. Этот показатель превышает результат подсчетов 2004 г., составивший 226,4 млн операций. Лишь 6,3% (95% ДИ: 1,7–22,9) и 23,1% (95% ДИ: 14,8–36,7) операций было проведено в государствах-членах с очень низким и низким уровнем расходов, что соотносится с 36,8% (2 573 млн людей) и 34,2% (2 393 млн людей) соответственно от общемирового населения, составляющего 7 001 млн людей. Доля кесаревых сечений составила 29,6% (5,8 из 19,6 млн операций; 95% ДИ: 9,7–91,7) от общего объема хирургических операций в государствах-членах с очень низким уровнем расходов и лишь 2,7% (5,1 из 187,0 млн операций; 95% ДИ: 2,2–3,4) в государствах-членах с высоким уровнем расходов.

Вывод

Объем операций значителен и увеличивается, и доля кесаревых сечений составляет приблизительно треть всех операций в странах, испытывающих острый недостаток ресурсов. Однако при этом в мире сохраняется неравномерное распределение ресурсов, необходимых для хирургических операций.

Introduction

Surgical care is essential for managing diverse health conditions – such as injuries, obstructed labour, malignancy, infections and cardiovascular disease – and an indispensable component of a functioning health system.1–3 International organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank, have highlighted surgery as an important component for global health development.3,4 However, surgical care requires coordination of skilled human resources, specialized supplies and infrastructure.

As low- and middle-income countries expand their economies and basic public health improves, noncommunicable diseases and injuries comprise a growing proportion of the disease burden.5 Investments in health-care systems have increased in the last decade, but the effect on surgical capacity is mostly unknown.6,7

Based on modelling of available data, it was estimated that 234.2 million operations were performed worldwide in 2004.8 The majority of these procedures took place in high-income countries (58.9%; 138.0 million), despite their relative lower share of the global population.

Here, we estimated the global volume of surgery in 2012. We also estimated the proportion of surgery due to caesarean delivery, since studies done in low-income countries have found that emergency obstetric procedures – especially caesarean deliveries – represent a high proportion of the total surgical volume.9,10

Methods

Population and health databases

For the years 2005 to 2012, we obtained population and health data for 194 WHO Member States. These data included total population, life expectancy at birth, percentage of total urban population, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in United States dollars (US$) and total health expenditure per capita in US$.6,11 For 11 Member States, where certain population or health data were not available from either WHO or the World Bank, we used data from other similar sources.12,13 All US$ were adjusted for inflation to the year 2012, using the consumer price index for general inflation.14 For Member States with reported surgical data, we also obtained population and health data from the year for which surgical volume was reported. We classified Member States based on their health spending. Member States spending US$ 0–100 per capita on health were classified as very-low-expenditure Member States (n = 50); US $101–400 as low-expenditure Member States (n = 54); US$ 401–1000 as middle-expenditure Member States (n = 46); and over US$ 1000 as high-expenditure Member States (n = 44).8

Surgical data sources

Operations were defined as procedures performed in operating theatres that require general or regional anaesthesia or profound sedation to control pain. We searched PubMed for the most recent annual surgical volume reported after 2004, using each Member State name along with the following keywords and phrases for all WHO Member States: “surgery”, “procedures”, “operations”, “national surgical volume” and “national surgical rate”. Depending on the Member State, we conducted our search in English, French and/or Spanish. To obtain email addresses for ministers or officials working for the ministry of health or individuals responsible for auditing surgical data at a national level, we searched the internet for the websites of ministries of health or national statistical offices. We contacted these persons to request the most recently reported total volume of operations based on the above definition.

From the database of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) we obtained surgical volume for 26 countries; 14 of these countries had total surgical volume data as well as detailed data for a subset of procedures (termed a shortlist by OECD), while the other 12 countries only had data for the shortlist.15 For the 14 countries, we used both data sets in combination with publicly available data on total health expenditure to define the relationship between the shortlist and the reported total surgical volume. We used this relationship to estimate total surgical volume for the 12 countries that only had shortlist and total health expenditure data. The average relative difference between the observed total surgical rate and extrapolated total surgical rate was 13.7% for these 14 countries; in a leave-one-out cross validation, the relative average bias was 16%.

For the Member States from which we obtained surgical data between 2005 and 2013, we calculated the annual surgical volume per 100 000 population for the year that the data were reported for the Member State by using the total population estimate for the same year.

Statistical analysis

Model development

To develop a predictive model for surgical rates, we first investigated the bivariate Spearman correlations between surgical rate and five a priori country-level variables: total population, life expectancy, percent urbanization, GDP per capita and total health expenditure per capita. We selected total health expenditure per capita as the only explanatory variable based on the results of Spearman correlations. We then did two sensitivity analyses: Spearman partial correlations and a multivariable regression model using the Lasso approach for variable selection.16

Our final predictive model contained only total health expenditure per capita. Finally, we log-transformed total health expenditure per capita and surgical rate to account for their right-skewed distribution.

Missing data analysis

To determine if any of the five a priori country-level predictors was related to the probability that a country’s surgical rate was missing, we fitted a multivariable logistic regression (Table 1).17 This model allowed us to determine variables associated with surgical rate. These variables could then be included in the imputation model to predict the rates for the Member States with missing data. The only variable significantly associated with whether a country’s surgical rate was missing was total health expenditure per capita, which was already included in the imputation model.

Table 1. Comparison of Member States of the World Health Organization with or without available surgical volume data, 2012.

| Characteristic | Member States with surgical data n = 66 | Member States without surgical data n = 128 | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Member States by region (%) | 0.319 | ||

| African Region | 9 (14) | 37 (29) | – |

| Region of the Americas | 11 (17) | 24 (19) | – |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 7 (11) | 15 (12) | – |

| European Region | 30 (45) | 23 (18) | – |

| South-East Asian Region | 5 (8) | 6 (5) | – |

| Western Pacific Region | 4 (6) | 23 (18) | – |

| Mean population size, in millions (95% CI) | 48.0 (6.4–89.7) | 29.9 (9.9–49.9) | 0.346 |

| Mean life expectancy, years (95% CI) | 73.9 (71.7–76.1) | 68.5 (66.9–70.1) | 0.128 |

| % of population living in urban areas (95% CI) | 62.9 (57.2–68.5) | 53.3 (49.2–57.3) | 0.772 |

| Mean GDP per capita, US$ (95% CI) | 21 745 (15 882–27 608) | 10 147 (6 493–13 801) | 0.219 |

| Mean total health expenditure per capita, US$ (95% CI) | 1 887 (1 315–2 460) | 616 (408–825) | 0.004 |

CI: confidence interval; GDP: gross domestic product; US$: United States dollars.

a P values are derived from a multivariate logistic regression model.

Note: Inconsistencies arise in some values due to rounding.

Imputation model

To find the best fitting model for the relation between surgical rate and total per capita health expenditure, we built a spline model, positing splines with zero, one, two or three inflection points.18–20 The best-fitting spline model was selected based on leave-one-out cross-validation, in which the predicted surgical rate value for a country was estimated based on a model that had been fitted after omitting data for that country. We used total per capita health expenditure from 2012 for our imputation model of surgical rates. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Somalia and Zimbabwe had no available total health expenditure data for 2012. Since the Pearson correlation between health expenditure in 2012 and any single year between 2000 and 2011 for all other Member States was ≥ 0.97, we extrapolated total health expenditure for these Member States by using their expenditure from previous years. As we did not have reported total health expenditure for 2013, we assumed that surgical rates or volume reported for 2013 were equivalent to 2012 values. For the 25 Member States with surgical data reported before 2012, we extrapolated 2012 estimates for these using a multiple imputation model that treated 2012 surgical rate data as missing for these 25 Member States.

For Member States with missing surgical volume data, we used multiple imputation and our predictive model to arrive at 2012 surgical rate estimates.21 We produced 300 imputed data sets to estimate the mean global surgical volume and its corresponding 95% confidence interval. Using the imputed country-level surgical rates and population estimates for 2012 we calculated the number of operations performed in each country in 2012. We also used published caesarean delivery data to calculate the proportion of surgical volume accounted for by caesarean delivery for each country.22 These data came primarily from the Global Health Observatory data repository,23 World Health Statistics 2010,24 the World Health Report 2010,25 the Demographic and Health Surveys26 and OECD.15

To compare the 2004 estimates with the new 2012 estimates, we used the same data on reported surgical rate from 56 countries that we used in the 2004 modelling exercise8 and did a spline analysis. We tested spline models with zero, one, two or three inflection points for the 2004 data. The spline model with two inflection points had the highest adjusted cross validation R2, as with the 2012 data. We evaluated the change in surgical rates that occurred for each health expenditure group between 2004 and 2012. This ensured that any observed changes in estimated volume were not driven by the updated modelling approach (details available from corresponding author).

We used SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, United States of America) for all statistical analyses. Two-sided statistical tests were done and all P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Model development

The total health expenditure per capita was the most highly correlated variable with surgical rate (Spearman correlation, r = 0.87297; P < 0.0001; Table 2; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/3/15-159293). The sensitivity analyses showed that after adjusting for total health expenditure per capita, none of the other variables remained significant. WHO regions were also not significantly associated with surgical rate (P = 0.09).

Table 2. Bivariate Spearman correlations between surgical rate and five a priori country-level variables and Spearman partial correlations adjusting for total health expenditure.

| Variable | Spearman correlation | P | Spearman partial correlation | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total health expenditure per capita | 0.87297 | < 0.0001 | NA | NA |

| Life expectancy | 0.77536 | < 0.0001 | −0.06327 | 0.6166 |

| GDP | 0.81359 | < 0.0001 | −0.24295 | 0.0512 |

| Urban population | 0.69607 | < 0.0001 | 0.00659 | 0.9585 |

| Population size | −0.18869 | 0.1292 | −0.11665 | 0.3548 |

GDP: gross domestic product; NA: not applicable.

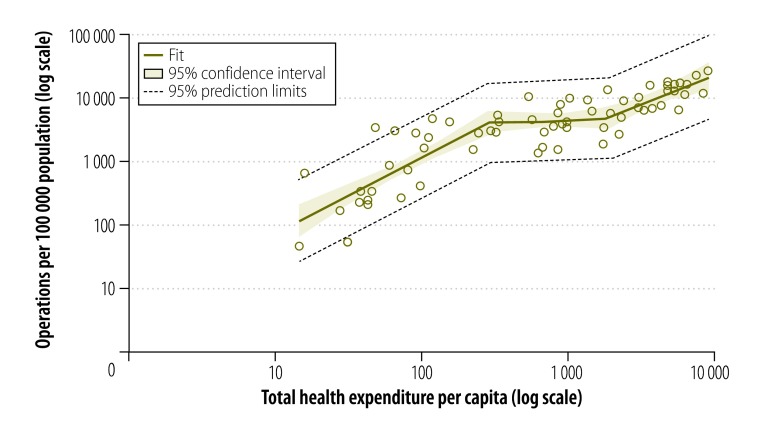

Fig. 1 shows the best fitting spline model for surgical rate based on total health expenditures, with two inflection points at US$ 288 and US$ 1950 per person per year (r2: 0.7449). The models with zero, one and three inflection points had adjusted cross validation r2 of 0.7064, 0.7071 and 0.7332 respectively.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between observed operations and total health expenditure per capita, 66 Member States of the World Health Organization, 2012

Notes: Total health expenditure adjusted to United States dollars (US$) for the year 2012. Correlation between observed operations and total health expenditure per capita was r = 0.87297 (P < 0.0001). The adjusted cross validation was r2 = 0.7449. Inflexion points correspond with adjusted total health expenditure per capita; the first inflexion point is US$ 288 and the second inflection point is US$ 1950.

Surgical volume

We obtained surgical data from 66 Member States (Table 3; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/3/15-159293). Using multiple imputation, we extrapolated the volume of surgery for each country without reported surgical data (Table 4; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/3/15-159293). For the year 2012, we estimated the total global volume to be 312.9 million operations – an increase of 38.2% from an estimated 226.4 million operations in 2004. The estimated mean global surgical rate was 4469 operations per 100 000 people per year (Table 5).

Table 3. Surgical rate and volume for 66 Member States of the World Health Organization with observed surgical data, 2005–2012.

| Member State (year of reported data) |

Population in 2012 | Total health expenditure per capitaa | Annual no. of operations | Annual no of operations per 100 000 populationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan (2008)27 | 29 824 536 | 37 | 61 920 | 229 |

| Armenia (2012)c,d | 2 969 081 | 150 | 123 861 | 4 172 |

| Australia (2012)28 | 22 723 900 | 6 140 | 2 477 096 | 10 901 |

| Austria (2012)c,29 | 8 429 991 | 5 407 | 1 178 284 | 13 977 |

| Bahrain (2012)30 | 1 317 827 | 895 | 51 992 | 3 945 |

| Bangladesh (2011)e,31 | 154 695 368 | 28 | 247 178 | 162 |

| Belgium (2012)32 | 11 128 246 | 4 711 | 1 976 833 | 17 764 |

| Bhutan (2012)33 | 741 822 | 90 | 19 954 | 2 690 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) (2010)34 | 10 496 285 | 112 | 228 622 | 2 251 |

| Bulgaria (2005)35 | 7 305 888 | 322 | 398 180 | 5 145 |

| Burkina Faso (2012)36 | 16 460 141 | 38 | 54 379 | 330 |

| Canada (2012)c,e,f,g,h37,38 | 34 754 312 | 5 741 | 2 382 956 | 6 857 |

| Chad (2012)39 | 12 448 175 | 31 | 6593 | 53 |

| China (2012)c,40 | 1 350 695 000 | 322 | 39 500 000 | 2 924 |

| Colombia (2012)i | 47 704 427 | 530 | 5 108 304 | 10 708 |

| Costa Rica (2012)41 | 4 805 295 | 951 | 202 519 | 4 214 |

| Cuba (2012)c,42 | 11 270 957 | 558 | 539 528 | 4 787 |

| Cyprus (2011)43 | 1 128 994 | 2 168 | 29 663 | 2 657 |

| Czech Republic (2012)c,44 | 10 510 785 | 1 432 | 658 811 | 6 268 |

| Denmark (2007)45 | 5 591 572 | 6 321 | 892 682 | 16 345 |

| El Salvador (2009)46 | 6 297 394 | 244 | 172 972 | 2 797 |

| Estonia (2012)47 | 1 325 016 | 1 010 | 126 883 | 9 576 |

| Ethiopia (2011)e,48 | 91 728 849 | 14 | 38 220 | 43 |

| Finland (2012)j | 5 413 971 | 4 232 | 428 000 | 7 905 |

| France (2012)32 | 65 676 758 | 4 690 | 10 709 393 | 16 306 |

| Georgia (2012)c,49 | 4 490 700 | 333 | 189 478 | 4 219 |

| Germany (2012)32 | 80 425 823 | 4 683 | 9 802 610 | 12 188 |

| Guatemala (2012)k | 15 082 831 | 226 | 231 288 | 1 533 |

| Hungary (2012)32 | 9 920 362 | 987 | 319 718 | 3 223 |

| Ireland (2012)32 | 4 586 897 | 3 708 | 299 335 | 6 526 |

| Israel (2012)l | 7 910 500 | 2 289 | 400 808 | 5 067 |

| Italy (2012)32 | 59 539 717 | 3 032 | 4 118 831 | 6 918 |

| Latvia (2011)50 | 2 034 319 | 843 | 119 184 | 5 791 |

| Liberia (2010)e,51 | 4 190 435 | 45 | 11 502 | 331 |

| Lithuania (2011)50 | 2 987 773 | 906 | 262 270 | 8 140 |

| Luxembourg (2012)32 | 530 946 | 7 452 | 116 452 | 21 933 |

| Mali (2009)52 | 14 853 572 | 48 | 450 260 | 3 321 |

| Malta (2012)m | 419 455 | 1 835 | 55 501 | 13 232 |

| Mexico (2012)n | 120 847 477 | 618 | 1 613 405 | 1 335 |

| Myanmar (2011)53 | 52 797 319 | 16 | 337 726 | 650 |

| Nepal (2011)54 | 27 474 377 | 42 | 56 768 | 209 |

| Netherlands (2012)32 | 16 754 962 | 5 737 | 2 787 778 | 16 639 |

| New Zealand (2012)c,55 | 4 433 000 | 3 292 | 280 310 | 6 323 |

| Nicaragua (2010)56 | 5 991 733 | 118 | 278 874 | 4 594 |

| Oman (2012)57 | 3 314 001 | 690 | 90 804 | 2 740 |

| Peru (2011)58 | 29 987 800 | 289 | 894 243 | 3 020 |

| Poland (2012)32 | 38 535 873 | 854 | 583 957 | 1 515 |

| Portugal (2011)59 | 10 514 844 | 2 350 | 890 965 | 8 439 |

| Qatar (2009)60 | 2 050 514 | 1 762 | 29 572 | 1 891 |

| Republic of Korea (2012)61 | 50 004 441 | 1 703 | 1 709 706 | 3 419 |

| Rwanda (2010)e,62 | 11 457 801 | 59 | 86 041 | 850 |

| Saudi Arabia (2012)63 | 28 287 855 | 795 | 1 002 474 | 3 544 |

| Sierra Leone (2012)64 | 5 978 727 | 96 | 24 152 | 404 |

| Slovakia (2012)65 | 5 407 579 | 1 326 | 475 111 | 8 786 |

| Slovenia (2012)32 | 2 057 159 | 1 942 | 116 009 | 5 639 |

| Spain (2010)66 | 46 761 264 | 3 056 | 4 657 900 | 10 110 |

| Sri Lanka (2006)67 | 19 858 000 | 89 | 579 820 | 2 920 |

| Sweden (2012)32 | 9 519 374 | 5 319 | 1 485 940 | 15 610 |

| Switzerland (2012)32 | 7 996 861 | 8 980 | 2 073 050 | 25 923 |

| Syrian Arab Republic (2010)68 | 22 399 254 | 105 | 339 825 | 1 578 |

| Turkey (2012)32 | 73 997 128 | 665 | 1 223 059 | 1 653 |

| Uganda (2011)e,48 | 36 345 860 | 42 | 84 874 | 241 |

| United Kingdom (2012)69 | 63 695 687 | 3 647 | 9 732 653 | 15 280 |

| United States (2007)70 | 313 873 685 | 8 895 | 36 457 210 | 12 087 |

| Yemen (2012)71 | 23 852 409 | 71 | 65 114 | 273 |

| Zambia (2010)o | 14 075 099 | 79 | 94 145 | 722 |

a Adjusted to 2012 United States dollars.

b Surgical rate is calculated using the total population for the year the surgical data were available.

c Surgical data from 2013.

d Data obtained via official communication with Armenian Ministry of Health, Armenia,13 August 2014.

e Regional rates extrapolated to entire country.

f Data obtained via official communication with Office of the Honourable Monica Ell, Nunavut Department of Health. Nunavut, Canada, 30 July 2014.

g Data obtained via official communication with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, data obtained from the Surgical Initiative database. Saskatchewan, Canada, 5 August 2014.

h Data obtained via official communication with the Office of Minister Doug Graham, Health and Social Services of Yukon, Canada, 15 August 2014.

i Data obtained via official communication with Dirección de Epidemiología y Demografía, Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, Colombia, 22 August 2014.

j Data obtained from Senior Planning Officer of the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland, 23 July 2014.

k Data obtained via official communication with Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social, Sistema de Información Gerencial de Salud – SIGSA. Viceminsterio de Hospitales, Guatemala, 10 July 2014.

l Data obtained from Head of Division of Health Information, Israeli Ministry of Health, Israel, 21 August 2014.

m Data obtained via personal communication. Distefano S, National Hospitals Information System, Directorate for Health Information & Research, Malta, 30 July 2014.

n Data obtained via personal communication with Rosas Osuna SR, Sistema Nacional de Información en Salud (SINAIS): Secretaría de Salud, Mexico Ministry of Health, Mexico, 12 March 2014.

o Data obtained via personal communication with Bowman K, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, United States of America, 17 April 2014

Table 4. Average imputed surgical rates and expected yearly number of operations, based on total health expenditure per capita, for 128 Member States of the World Health Organization with missing surgical volume data, 2012.

| Country | Population in 2012 | Total health expenditure per capitaa | Average imputed no. of operations per 100 000 population per year | Expected range of operations in 2012b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 2 801 681 | 228 | 4 991 | 123 393–156 263 |

| Algeria | 38 481 705 | 279 | 6 663 | 2 253 295–2 875 033 |

| Andorra | 78 360 | 3 057 | 9 263 | 5 980–8 537 |

| Angola | 20 820 525 | 190 | 4 812 | 867 905–1 136 052 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 89 069 | 681 | 5 210 | 3 962–5 319 |

| Argentina | 41 086 927 | 995 | 5 519 | 1 993 467–2 541 889 |

| Azerbaijan | 9 295 784 | 398 | 4 225 | 339 029–446 449 |

| Bahamas | 371 960 | 1 647 | 7 067 | 22 715–29 857 |

| Barbados | 283 221 | 938 | 5 303 | 13 256–16 779 |

| Belarus | 9 464 000 | 339 | 4 593 | 373 612–495 757 |

| Belize | 324 060 | 259 | 6 199 | 17 214–22 965 |

| Benin | 10 050 702 | 33 | 406 | 35 503–46 076 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 3 833 916 | 447 | 4 859 | 158 739–213 844 |

| Botswana | 2 003 910 | 384 | 4 674 | 80 047–107 289 |

| Brazil | 198 656 019 | 1 056 | 6 128 | 10 500 890–13 844 633 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 412 238 | 939 | 5 740 | 20 850–26 472 |

| Burundi | 9 849 569 | 20 | 217 | 18 381–24 422 |

| Cabo Verde | 494 401 | 144 | 2 636 | 11 225–14 836 |

| Cambodia | 14 864 646 | 51 | 666 | 86 263–111 749 |

| Cameroon | 21 699 631 | 59 | 816 | 154 105–200 182 |

| Central African Republic | 4 525 209 | 18 | 165 | 6 607–8 307 |

| Chile | 17 464 814 | 1 103 | 5 462 | 843 337–1 064 491 |

| Comoros | 717 503 | 38 | 470 | 2 916–3 826 |

| Congo | 4 337 051 | 100 | 1 568 | 60 014–76 016 |

| Cook Islands | 10 777 | 511 | 4 760 | 403–623 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 19 839 750 | 88 | 1 481 | 259 012–328 483 |

| Croatia | 4 267 558 | 908 | 5 798 | 218 765–276 118 |

| Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 24 763 188 | 76 | 1 298 | 276 561–366 155 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 65 705 093 | 15 | 144 | 82 327–106 897 |

| Djibouti | 859 652 | 129 | 2 576 | 19 458–24 832 |

| Dominica | 71 684 | 392 | 4 717 | 2 805–3 959 |

| Dominican Republic | 10 276 621 | 310 | 4 153 | 377 226–476 327 |

| Ecuador | 15 492 264 | 361 | 4 538 | 610 398–795 822 |

| Egypt | 80 721 874 | 152 | 2 889 | 2 066 134–2 598 531 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 736 296 | 1 138 | 5 834 | 37 487–48 421 |

| Eritrea | 6 130 922 | 15 | 147 | 7 796–10 238 |

| Fiji | 874 742 | 177 | 3 487 | 26 874–34 128 |

| Gabon | 1 632 572 | 397 | 4 471 | 63 539–82 433 |

| Gambia | 1 791 225 | 26 | 311 | 4 715–6 426 |

| Ghana | 25 366 462 | 83 | 1 338 | 296 538–382 153 |

| Greece | 11 092 771 | 2 044 | 5 886 | 570 323–735 563 |

| Grenada | 105 483 | 478 | 4 769 | 4 391–5 669 |

| Guinea | 11 451 273 | 32 | 384 | 38 463–49 596 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 663 558 | 30 | 333 | 4 788–6 289 |

| Guyana | 795 369 | 235 | 5 771 | 39 069–52 737 |

| Haiti | 10 173 775 | 53 | 776 | 66 467–91 429 |

| Honduras | 7 935 846 | 195 | 4 198 | 294 312–372 041 |

| Iceland | 320 716 | 3 872 | 12 163 | 33 989–44 026 |

| India | 1 236 686 732 | 61 | 904 | 9 801 319–12 556 488 |

| Indonesia | 246 864 191 | 108 | 1 839 | 3 957 879–5 120 005 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 76 424 443 | 490 | 4 106 | 2 767 543–3 508 289 |

| Iraq | 32 578 209 | 226 | 5 409 | 1 521 217–2 003 067 |

| Jamaica | 2 707 805 | 318 | 4 337 | 103 013–131 876 |

| Japan | 127 561 489 | 4 752 | 14 508 | 16 388 287–20 626 119 |

| Jordan | 6 318 000 | 388 | 4 475 | 248 911–316 588 |

| Kazakhstan | 16 791 425 | 521 | 4 972 | 731 544–938 337 |

| Kenya | 43 178 141 | 45 | 619 | 232 365–301 898 |

| Kiribati | 100 786 | 187 | 3 998 | 3 468–4 591 |

| Kuwait | 3 250 496 | 1 428 | 5 971 | 172 105–216 085 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 5 607 200 | 84 | 1 390 | 68 768–87 164 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 6 645 827 | 40 | 508 | 29 864–37 621 |

| Lebanon | 4 424 888 | 650 | 5 425 | 206 805–273 335 |

| Lesotho | 2 051 545 | 138 | 2 777 | 50 047–63 910 |

| Libya | 6 154 623 | 578 | 4 831 | 260 219–334 448 |

| Madagascar | 22 293 914 | 18 | 175 | 34 593–43 541 |

| Malawi | 15 906 483 | 25 | 297 | 41 090–53 311 |

| Malaysia | 29 239 927 | 419 | 4 537 | 1 177 889–1 475 530 |

| Maldives | 338 442 | 558 | 5 070 | 14 551–19 770 |

| Marshall Islands | 52 555 | 590 | 5 063 | 2 292–3 030 |

| Mauritania | 3 796 141 | 52 | 702 | 23 302–29 963 |

| Mauritius | 1 291 167 | 444 | 4 493 | 51 187–64 848 |

| Micronesia (Federal States of) | 103 395 | 405 | 4 537 | 4 042–5 340 |

| Monaco | 37 579 | 6 708 | 20 262 | 6 563–8 666 |

| Mongolia | 2 796 484 | 232 | 4 908 | 120 159–154 342 |

| Montenegro | 621 081 | 493 | 5 110 | 27 903–35 568 |

| Morocco | 32 521 143 | 190 | 3 929 | 1 104 656–1 450 854 |

| Mozambique | 25 203 395 | 37 | 496 | 108 974–141 142 |

| Namibia | 2 259 393 | 473 | 4 785 | 92 473–123 729 |

| Nauru | 9 378 | 564 | 4 674 | 347–529 |

| Niger | 17 157 042 | 25 | 293 | 43 349–57 053 |

| Nigeria | 168 833 776 | 94 | 1 596 | 2 360 057–3 028 546 |

| Niue | 1 269 | 1 270 | 6 365 | 47–115 |

| Norway | 5 018 573 | 9 055 | 29 239 | 1 276 741–1 657 982 |

| Pakistan | 179 160 111 | 34 | 423 | 656 418–859 980 |

| Palau | 20 754 | 972 | 6 552 | 1 138–1 581 |

| Panama | 3 802 281 | 723 | 5 194 | 174 850–220 103 |

| Papua New Guinea | 7 167 010 | 114 | 2 076 | 130 103–167 403 |

| Paraguay | 6 687 361 | 392 | 4 386 | 253 242–333 423 |

| Philippines | 96 706 764 | 119 | 2 385 | 2 005 550–2 607 277 |

| Republic of Moldova | 3 559 519 | 239 | 5 789 | 178 368–233 757 |

| Romania | 20 076 727 | 420 | 5 134 | 887 449–1 174 096 |

| Russian Federation | 143 178 000 | 887 | 5 577 | 6 938 584–9 031 846 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 53 584 | 825 | 5 492 | 2 478–3 408 |

| Saint Lucia | 180 870 | 556 | 4 578 | 7 266–9 293 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 109 373 | 340 | 4 734 | 4 303–6 053 |

| Samoa | 188 889 | 245 | 5 609 | 9 101–12 087 |

| San Marino | 31 247 | 3 792 | 11 921 | 3 222–4 228 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 188 098 | 109 | 1 990 | 3 173–4 311 |

| Senegal | 13 726 021 | 51 | 715 | 84 466–111 699 |

| Serbia | 7 199 077 | 561 | 5 068 | 316 905–412 754 |

| Seychelles | 88 303 | 521 | 4 858 | 3 772–4 806 |

| Singapore | 5 312 400 | 2 426 | 7 275 | 335 808–437 171 |

| Solomon Islands | 549 598 | 148 | 3 016 | 14 468–18 681 |

| Somalia | 10 195 134 | 20 | 231 | 19 986–27 089 |

| South Africa | 52 274 945 | 645 | 4 991 | 2 235 713–2 982 830 |

| South Sudan | 10 837 527 | 27 | 311 | 29 067–38 266 |

| Sudan | 37 195 349 | 115 | 2 042 | 658 712–860 547 |

| Suriname | 534 541 | 521 | 4 947 | 22 660–30 230 |

| Swaziland | 1 230 985 | 259 | 6 176 | 66 589–85 453 |

| Tajikistan | 8 008 990 | 55 | 764 | 53 256–69 118 |

| Thailand | 66 785 001 | 215 | 4 775 | 2 756 949–3 621 426 |

| The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | 2 105 575 | 327 | 4 476 | 81 800–106 710 |

| Timor-Leste | 1 148 958 | 50 | 684 | 6 835–8 892 |

| Togo | 6 642 928 | 41 | 530 | 30 889–39 566 |

| Tonga | 104 941 | 238 | 5 650 | 5 016–6 842 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 337 439 | 972 | 5 865 | 68 535–88 354 |

| Tunisia | 10 777 500 | 297 | 4 627 | 420 162–577 232 |

| Turkmenistan | 5 172 931 | 129 | 2 460 | 111 503–143 051 |

| Tuvalu | 9 860 | 577 | 5 017 | 389–601 |

| Ukraine | 45 593 300 | 293 | 4 882 | 1 891 091–2 560 965 |

| United Arab Emirates | 9 205 651 | 1 343 | 5 891 | 473 401–611 217 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 47 783 107 | 41 | 454 | 193 051–240 876 |

| Uruguay | 3 395 253 | 1 308 | 6 256 | 186 105–238 742 |

| Uzbekistan | 29 774 500 | 105 | 1 878 | 492 861–625 376 |

| Vanuatu | 247 262 | 116 | 2 084 | 4 480–5 827 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 29 954 782 | 593 | 5 376 | 1 383 223–1 837 617 |

| Viet Nam | 88 772 900 | 102 | 1 865 | 1 459 314–1 852 719 |

| Zimbabwe | 13 724 317 | 228 | 5 168 | 620 938–797 504 |

a Adjusted to 2012 United States dollars.

b Ranges for volume of surgery are derived from the 99% prediction interval from 300 imputed data sets for each country based on total health expenditure per capita.

Table 5. Comparative rate and volume of surgery for Member States of the World Health Organization, by total health expenditure group, 2004 and 2012.

| Variable | Member State total health expenditure groupa |

Global | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low |

Low |

Middle |

High |

|||||||||||

| 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | |||||

| No. of Member States | 47 | 50 | 60 | 54 | 47 | 46 | 38 | 44 | 192 | 194 | ||||

| Population, in millions (% of global population) | 2248 (34.8) | 2573 (36.8) | 2258 (35.0) | 2393 (34.2) | 940 (14.7) | 799 (11.4) | 1007 (15.6) | 1236 (17.7) | 6453 (100) | 7001 (100) | ||||

| Mean estimated surgical rate, per 100 000 population per year (95% CI) | 394 (273–516) | 666 (465–867) | 1851 (1162–2540) | 3973 (2 320–5625) | 3944 (2857–5030) | 4822 (3085–6560) | 11 629 (9560–13 697) | 11 168 (9151–13 186) | 3941 (3333–4541) | 4469 (3693–5245) | ||||

| Change in surgical rate, % (95% CI) |

– | 69.0 (9.9–160.0) | – | 114.6 (23.1–274.2) | – | 22.3 (−22.2–92.1) | – | −4.0 (−25.4–23.6) | – | – | ||||

| Estimated no. of surgeries in millions (95% CI) | 14.0 (1.8–26.2) | 19.6 (7.4–51.7) | 41.4 (5.6–77.3) | 72.2 (56.7–91.9) | 31.9 (19.3–44.5) | 34.1 (19.8–58.7) | 139.0 (131.5–146.4) | 187.0 (155.8–224.5) | 226.4 (181.9–270.8) | 312.9 (266.2–359.5) | ||||

| % of global volume of surgery (95% CI) | 6.2 (1.9–21.5) | 6.3 (1.7–22.9) | 18.3 (5.5–63.2) | 23.1 (14.8–36.7) | 14.1 (7.2–28.5) | 10.9 (5.0–24.5) | 61.4 (46.5–84.1) | 59.8 (41.0–88.8) | 100 (NA) | 100 (NA) | ||||

CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable; US$: United States dollars.

a Total health expenditure adjusted to US$ for the year 2012. Very low-expenditure Member States were defined as per capita total expenditure on health of US$ 100 or less; low-expenditure Member States as US$ 101–400; middle-expenditure Member States as US$ 401–1000; and high-expenditure Member States as more than US$ 1000.

Note: Inconsistencies arise in some values due to rounding.

The rate of surgery increased significantly for all Member States spending US$ 400 or less per capita in total health expenditures (Table 5). Across the health expenditure brackets, mean estimated surgical rates in 2012 ranged from 666 to 11 168 operations per 100 000 people. Of the total global volume of surgery, 6.3% (19.6/312.9 million operations) was performed in very-low-expenditure Member States which accounted for 36.8% (2.573/7.001 billion people) of the world’s population in 2012, while 59.8% (187.0/312.9 million operations) of the surgical volume took place in the high-expenditure Member States which account for 17.7% (1.236/7.001 billion people) of the world’s population. The biggest increase in the rate of surgery occurred in very-low- and low-expenditure Member States (69.0%; from 394 to 666 operations per 100 000 population per year and 114.6%, from 1851 to 3973 operations per 100 000 population per year, respectively), while middle- and high-expenditure Member States experienced no significant change.

Caesarean delivery data were more widely available than overall surgical data, with data from 172 Member States. In very-low-expenditure settings, caesarean delivery accounted for 29.6% (5.8/19.6 million operations) of all operations performed. However, in high-expenditure Member States this percentage was only 2.7% (5.1/187.0 million operations; Table 6). Worldwide, caesarean deliveries account for nearly one in every 14 operations performed.

Table 6. Volume and proportional contribution of caesarean delivery for Member States of the World Health Organization, by total health expenditure group, 2012.

| Caesarean delivery | Member State health expenditure groupa |

Global | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | Low | Middle | High | ||

| Estimated no. in millions (95% CI) | 5.8 (5.8–5.9) | 7.8 (7.8–7.9) | 4.1 (4.0–4.3) | 5.1 (5.0–5.1) | 22.9 (22.5–23.2) |

| % of caesarean deliveries (95% CI) |

25.5 (24.9–26.0) | 34.2 (33.7–34.8) | 18.0 (17.1–19.0) | 22.2 (21.9–22.6) | 100 (NA) |

| % of global volume of surgery (95% CI) | 29.6 (9.7–91.7) | 10.8 (8.2–14.4) | 12.1 (6.2–23.5) | 2.7 (2.2–3.4) | 7.3% (6.1–9.0) |

CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable; US$: United States dollars.

a Total health expenditure adjusted to US$ for the year 2012. Very low-expenditure Member States were defined as per capita total expenditure on health of US$ 100 or less; low-expenditure Member States as US$ 101–400; middle-expenditure Member States as US$ 401–1000; and high-expenditure Member States as more than US$ 1000.

Note: Inconsistencies arise in some values due to rounding.

Discussion

We estimate 266.2 to 359.5 million operations were performed in 2012. This represents an increase of 38% over the previous eight years. We note the largest increase in operations was in very-low- and low-expenditure Member States. However, about one in every 20 operations globally was done in very-low-expenditure Member States, despite these Member States representing well over one third of the total global population. Comparing very-low-expenditure Member States with high-expenditure Member States, the gap in access is even larger. These disparities may be even larger when examining the distribution of access to surgical care within individual Member States, an undertaking that is beyond the scope of this study.

The proportion of caesarean delivery were higher in Member States with lower surgical volume. This likely demonstrates that obstetrical emergencies are prioritized as a surgical intervention in Member States with scarce resources, but also suggests that other surgical conditions are left poorly attended in these settings. The findings serve to highlight the importance of improving surgical capacity to address both obstetrical and other surgical conditions.

Surgical data were lacking from many Member States. Compared with the data availability for the 2004 estimates, only 10 more Member States now had available data. This contrasted with caesarean delivery data, which were available for the majority of Member States. Given the efforts of the maternal health community and the importance of caesarean delivery in supporting improved maternal outcomes, our findings are not surprising. The challenge of accessing data on surgical care impede the understanding and monitoring of surgery as a component of global health care. Without standardized and accessible data, it is difficult for researchers and policy-makers to contextualize and prioritize surgical access and quality when discussing health system strengthening.

In 2015, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage.72 The increases in injuries and noncommunicable diseases present a challenge for weak health systems already struggling with a high infectious burden of disease.73 Not only do injuries and many noncommunicable diseases require surgical intervention, in many resource-poor settings neglected infections – such as typhoid and tuberculosis – are not treated in a timely fashion and therefore require surgical care.74

The increase in surgical output in very-low-expenditure Member States over the last eight years suggests that these Member States are placing an increasing importance on access to emergency and essential surgical services. However, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery has estimated that five billion people lack access to safe, affordable surgical and anaesthesia care when needed and an additional 143 million operations are required to address emergency and essential conditions in low- and middle-income countries.3

The lack of standardized surgical data globally is both a limitation of and the reason for undertaking this study. As part of the WHO Safe Surgery Saves Lives programme for which the 2004 estimates of global surgical volume was performed, our group proposed a standard set of metrics for surgical surveillance.75 We continued to have difficulty during this study obtaining standardized data regarding surgical intervention. The data were not located or reported in any standardized way and required our research team to compile the information from multiple agencies, ministries, health reports and published literature, as there was no central source for collecting or reporting these data. Some ministry reports may include only state and government facilities and not hospitals run privately or by nongovernmental organizations, which can provide substantial surgical capacity. Thus the volume we report may be an underestimate. Regardless, the non-included facilities are unlikely to close the gap in care between Member States or change our findings. In addition, there was no differentiation between surgical care undertaken in urban versus rural areas. There is likely a large discrepancy in surgical access and provision of surgical care within a single country.

OECD, which had previously collected total operative volume as reported in our last study,8 has changed its methods and now reports on only a subset of procedures. Thus our analysis required an additional step to turn these data into comprehensive estimates of volume, adding another layer of uncertainty.

Many of the same limitations of the previous analysis were present here. We focused on operations performed in an operating theatre as these are most likely to involve high complexity, acuity and risk. Our study is thus limited by the manner in which such operations and procedures are recorded. We recognize that many minimally invasive procedures can be undertaken outside an operating theatre, as can many image-guided procedures, thus potentially undercounting what might be considered surgery in these settings. Many minor procedures may also be undertaken in the operating room to improve pain control or exposure or because of availability of resources and equipment, thus creating variability within our count. However, by standardizing our definition, we limited the difficulties associated with the variability in case mix and practice patterns across Member States and settings.

As only one third of Member States reported data on surgical volume, our estimates of overall volume of surgery continue to rely on modelling techniques. We noted changes in the slope of the curve of our spline regression over the range of health expenditure, in particular between the two spline inflections, likely reflecting the heterogeneity of Member States. Furthermore, while the imputation strategy was aimed at a global estimate, the estimate for any particular country may be imprecise. However, our modelling strategy was based on the strong explanatory power of per capita expenditure on health as a determinant of surgical volume. Health expenditure per capita was the only variable that was significantly associated with whether surgical rate data was missing, and multiple imputation protects against systemic bias from data that are missing at random.

Conclusion

Surgical volume continues to grow, particularly in very-low- and low-expenditure Member States. However, surgical surveillance continues to be weak and poorly standardized and limits the precision of these estimates, yet the systematic evaluation of access, capacity, delivery and safety of care is paramount if surgical services are to support a programme of health system strengthening. Furthermore, the relationship of surgical provision to population health outcomes is not clear, and interventions such as surgery that include substantial risk to patients must be carefully considered. Many patients receive surgical care, yet safety and quality-of-care remain poorly measured and a low priority in many Member States.

Acknowledgements

TGW and ABH contributed equally to this manuscript. We thank Ulrike Schermann-Richter (Austrian Ministry of Health), Pandup Tshering (Bhutanese Ministry of Health), Ana Carolina Estupiñan Galindo (Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection), Rasilainen Jouni (Finnish National Institute For Health And Welfare), Marina Shakh-Nazarova (Georgian National Center for Disease Control and Public Health), Ziona Haklai (Israelean Ministry of Health), Sandra Distefano (Maltese, Ministry for Energy and Health), Juan Alejandro Urquizo Soriano (Peruvian National Institute of Neoplastic Diseases) and Jan Mikas (Slovak Ministry of Health).

Funding:

Salary support for TGW, MME and TUL came from the Stanford Department of Surgery, Stanford, USA. Salary support for ABH, SRL, WRB and AAG came from Ariadne Labs, Boston, USA. Salary support for GM and TEC came from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, Boston, USA.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Farmer PE, Kim JY. Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg. 2008. April;32(4):533–6. 10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luboga S, Macfarlane SB, von Schreeb J, Kruk ME, Cherian MN, Bergström S, et al. ; Bellagio Essential Surgery Group (BESG). Increasing access to surgical services in sub-Saharan Africa: priorities for national and international agencies recommended by the Bellagio Essential Surgery Group. PLoS Med. 2009. December;6(12):e1000200. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015. August 8;386(9993):569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safe Surgery. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/ [cited 2016 Jan 22].

- 5.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012. December 15;380(9859):2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World development indicators. Washington: World Bank; 2014. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicatorhttp://[cited 2014 Sept 23].

- 7.Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013. December 7;382(9908):1898–955. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008. July 12;372(9633):139–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes CD, McClain CD, Hagander L, Pierre JH, Groen RS, Kushner AL, et al. Ratio of caesarean deliveries to total operations and surgeon nationality are potential proxies for surgical capacity in central Haiti. World J Surg. 2013. July;37(7):1526–9. 10.1007/s00268-012-1794-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petroze RT, Mehtsun W, Nzayisenga A, Ntakiyiruta G, Sawyer RG, Calland JF. Ratio of caesarean sections to total procedures as a marker of district hospital trauma capacity. World J Surg. 2012. September;36(9):2074–9. 10.1007/s00268-012-1629-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World health statistics. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/datahttp://[cited 2014 Sept 10].

- 12.The world factbook: country listings. Langley: Central Intelligence Agency; 2014. Available from: http://www.emprendedor.com/factbook/countrylisting.htmlhttp://[cited 2014 Sept 10].

- 13.World statistics pocketbook. New York: United Nations Statistics Division; 2014. Available from: https://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspxhttp://[cited 2014 Sept 10].

- 14.Inflation calculator [Internet]. Washington: United States Bureau of Labor and Statistics; 2014. Available from: http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.plhttp://[cited 2014 Sept 22].

- 15.OECD health statistics [Internet]. Paris: Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development; 2014. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?r=439572 [cited 2014 Oct 3].

- 16.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1996;58:267–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996. December;49(12):1373–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PL. Splines as a useful and convenient statistical tool. Am Stat. 1979;33(2):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eilers PHC, Marx BD. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalties. Stat Sci. 1996;11(2):89–102. 10.1214/ss/1038425655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Boor C. A practical guide to splines. Berlin: Springer; 1978. 10.1007/978-1-4612-6333-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: J Wiley & Sons; 1987 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-Leitz T, Azad T, et al. Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2263-70. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Global Health Observatory data repository: Births by caesarean section [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.REPWOMEN39?lang=enhttp://[cited 2014 Oct 3].

- 24.World health statistics 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demographic and health surveys; STATcompiler. Washington: USAID; 2014. Available from: http://www.statcompiler.comhttp://[cited 2014 Sept 22].

- 27.Balanced scorecard report for provincial and Kabul hospitals [Internet]. Kabul: Afghan Ministry of Public Health; 2008. Available from: http://moph.gov.af/Content/Media/Documents/Hospital-Balanced-Scorecard-Report-2008-English51201111561950.pdf [cited 2014 May 29].

- 28.Australian hospital statistics: surgery in Australian hospitals 2012–2013 [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2014. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129547095 [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 29.Austria data source [Internet]. Vienna: EuroREACH; 2013. Available from: http://www.healthdatanavigator.eu/national/austria/80-data-source/129-austria-data-ource [cited 2014 Aug 5].

- 30.Health statistics 2012 [Internet]. Manama: Bahraini Ministry of Health; 2012. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.bh/PDF/Publications/statistics/HS2012/hs2012_e.htm [cited 2014 May 22].

- 31.LeBrun DG, Dhar D, Sarkar MI, Imran TM, Kazi SN, McQueen KA. Measuring global surgical disparities: a survey of surgical and anesthesia infrastructure in Bangladesh. World J Surg. 2013. January;37(1):24–31. 10.1007/s00268-012-1806-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health care utilization: surgical procedures (shortlist). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2012. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30167# [cited 2014 Aug 20].

- 33.Annual health bulletin [Internet]. Thimphu: Ministry of Health, Royal Government of Bhutan; 2013. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/ftps/annual-health-bulletins/ahb2013/ahbContent2013.pdf [cited 2014 Apr 12].

- 34.LeBrun DG, Saavedra-Pozo I, Agreda-Flores F, Burdic ML, Notrica MR, McQueen KA. Surgical and anesthesia capacity in Bolivian public hospitals: results from a national hospital survey. World J Surg. 2012. November;36(11):2559–66. 10.1007/s00268-012-1722-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Public health statistics [Internet]. Sofia: Bulgarian Ministry of Health; 2006. Available from: http://ncphp.government.bg/files/nczi/izdania_2010/healthcare_06a.pdf [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 36.Annuaire statistique 2012 [Internet]. Ouagadougou: Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso; 2012. Available from: http://www.sante.gov.bf/index.php/publications-statistiques/file/338-annuaire-statistique-2012 [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 37.Alberta health care insurance plan: claims files from Alberta Ministry of Health July 30 2014. Edmonton: Alberta Ministry of Health; 2014.

- 38.Provincial hospital discharge abstract database August 22 2014. Victoria: Ministry of Health, Province of British Columbia; 2014.

- 39.Annuaire des statistiques sanitaires du Tchad 2012 [Internet]. N’Djamena: Ministrè de la Santé Publique; 2012. Available from: http://www.sante-tchad.org/ANNUAIRE-DES-STATISTIQUES-SANITAIRES-DU-TCHAD-ANNEE-2012_a42.html [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 40.Surgical procedure volumes: global analysis (US, China, Japan, Brazil, UK, Germany, Italy, France, Mexico, Russia). New York: Kalorama Information; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Área de estadísticas en salud de la caja costarricense de seguro social [Internet]. San José: Costa Rican Ministry of Health; 2012 Available from: http://www.ccss.sa.cr/est_salud [cited 2014 Aug 22].

- 42.Anuario estadístico de salud [Internet]. Havana: Biblioteca Virtual en Salud de Cuba; 2012. p. 157. Available from: http://bvscuba.sld.cu/anuario-estadistico-de-cuba/ [cited 2014 July 24].

- 43.Statistical service [Internet]. Nicosia: Health and Hospital Statistics Republic of Cyprus; 2011. Available from: http://www.mof.gov.cy/mof/cystat/statistics.nsf/All/39FF8C6C587B26A6C22579EC002D5471/$file/HEALTH_HOSPITAL_STATS-2011-270114.pdf?OpenElementhttp://[cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 44.Health statistic [Internet]. Prague: Institute of Health Information and Statistics of the Czech Republic; 2012. Available from: http://www.uzis.cz/en/category/edice/publications/health-statistic [cited 2014 Aug 14].

- 45.Health care in Denmark [Internet]. Copenhagen: Danish Ministry of Health and Prevention; 2008. p. 48. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/travail/docs/2047/health%20in%20Denmark.pdf [cited 2014 Jul 16].

- 46.Molina G, Funk LM, Rodriguez V, Lipsitz SR, Gawande A. Evaluation of surgical care in El Salvador using the WHO surgical vital statistics. World J Surg. 2013. June;37(6):1227–35. 10.1007/s00268-013-1990-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Health statistics and health research database, surgical procedures. KP11 inpatient and day surgery by service type, gender and age group [Internet]. Tallinn: Estonian National Institute for Health Development; 2012. Available from: http://pxweb.tai.ee/esf/pxweb2008/Dialog/varval.asp?ma=KP11&ti=KP11%3A+Inpatient+and+day+surgery+by+service+type%2C+gender+and+age+group&path=../Database_en/HCservices/05Surgery/&lang=1 [cited 2014 Jul 16].

- 48.LeBrun DG, Chackungal S, Chao TE, Knowlton LM, Linden AF, Notrica MR, et al. Prioritizing essential surgery and safe anesthesia for the Post-2015 Development Agenda: operative capacities of 78 district hospitals in 7 low- and middle-income countries. Surgery. 2014. March;155(3):365–73. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Health statistical database, national centre for control and public health. Tbilisi: Georgian Ministry of Labour Health and Social Affairs; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Health in the Baltic countries 2011 [Internet]. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of Hygiene Health Information Centre; 2013. Available from: http://sic.hi.lt/data/baltic11.pdf [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 51.Knowlton LM, Chackungal S, Dahn B, LeBrun D, Nickerson J, McQueen K. Liberian surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: a survey of county hospitals. World J Surg. 2013. April;37(4):721–9. 10.1007/s00268-013-1903-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Système national d’information sanitaire [Internet]. Bamako: Ministère de la Sante de la Répulique du Mali; 2009. Available from: http://41.73.116.156/docs/pdf/AnnuaireSNIS2009.pdf [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 53.Annual hospital statistics report 2010–2011 [Internet]. Nay Pyi Taw: Ministry of Health of Myanmar; 2013. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.mm/file/Annual%20Hospital%20Statistics%20Report%202010-2011.pdf [cited 2014 Apr 6].

- 54.Annual report [Internet]. Kathmandu: Nepalese Ministry of Health and Population; 2011. Available from: http://dohs.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Annual_report_2067_68_final.pdf [cited 2014 Mar 15].

- 55.National minimum dataset (NMDS). Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Health; 2014. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/collections/national-minimum-dataset-hospital-events [cited 2016 Jan 28].

- 56.Solis C, León P, Sanchez N, Burdic M, Johnson L, Warren H, et al. Nicaraguan surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: survey of Ministry of Health hospitals. World J Surg. 2013. September;37(9):2109–21. 10.1007/s00268-013-2112-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Utilization of health services. [Internet] Muscat: Omani Ministry of Health; 2012. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.om/en/stat/2012/index_eng.htm [cited 2014 May 22].

- 58.Memoria Institucional de Essalud [Internet]. Lima: Peruvian Ministry of Health; 2011. pp. 1–49. Available from: http://www.essalud.gob.pe/downloads/memorias/memoria2011.pdf [cited 2014 Aug 10].

- 59.Statistical information – list navigation [Internet]. Lisbon: Statistics Portugal; 2011. Available from: http://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_base_dados [cites 2014 Jul 17].

- 60.Qatar health report 2009: planning for the future [Internet]. Doha: National Heath Strategy; 2011. Available from: http://www.nhsq.info/app/media/1147 [cited 2014 May 14].

- 61.Main Surgery Statistical Yearbook 2012. Seoul: National Health Insurance Service, Democratic People's Republic of Korea; 2012. pp. 1–518. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V, Ntakiyiruta G, Calland JF. Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. Br J Surg. 2012. March;99(3):436–43. 10.1002/bjs.7816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Health statistics annual book [Internet]. Riyadh: Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health; 2012. pp.177-184. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/1433.pdf [cited 2014 May 14].

- 64.Bolkan H, Samai M, Bash-Taqi D, Buya Kamara T, Fadlu-Deen G, Salvesen Ø, et al. Surgery in Sierra Leone: Nationwide surgical activity and surgical provider resources in 2012. Trondheim: CapaCare; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Health statistics yearbook of the Slovak Republic 2012 [Internet]. Bratislava: Slovak National Health Information Center; 2014. pp. 1–255. Available from: http://www.nczisk.sk/Documents/rocenky/rocenka_2012.pdf [cited 2014 Jul 30].

- 66.Sistema nacional de salud España 2012 [Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2012. p. 38. Available from: https://www.msssi.gob.es/en/organizacion/sns/docs/sns2012/SNS012__Espanol.pdf [cited 2014 Jul 16].

- 67.Progress and performance report 2012–2013 [Internet]. Colombo: Sri Lankan Ministry of Health; 2012. Available from: http://www.health.gov.lk/en/publication/P-PReport2012.pdf/PerformanceReport2012-E.pdf [cited 2014 Apr 10].

- 68.Surgical operations in MOH hospitals [Internet]. Damascus: Syrian Ministry of Health; 2010. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sy/Default.aspx?tabid=250&language=en-US#13. [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 69.Hospital episode statistics, admitted patient care, England – 2012–13. Main procedures and interventions. Leeds: Health & Social Care Information Centre; 2013. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=13264&q=title%3a%22Hospital+Episode+Statistics%2c+Admitted+patient+care+-+England%22&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1#top [cited 2014 Jul 16].

- 70.Russo C, Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Wier L. Hospital-based ambulatory surgery, 2007. HCUP statistical brief #86. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb86.pdf [cited 2015 Jan 25]. [PubMed]

- 71.Annual statistical health report [Internet]. Sana’a: Yemeni Ministry of Public Health and Population; 2012. Available from: http://www.mophp-ye.org/arabic/docs/Report2012.pdf [cited 2014 Oct 4].

- 72.Resolution WHA68.15. Strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage. In: Sixty-eighth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 18–26 May 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Marquez PV, Farrington JL. The challenge of non-communicable diseases and road traffic injuries in sub-Saharan Africa. An overview. Washington: The World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jarnheimer A, Kantor G, Bickler S, Farmer P, Hagander L. Frequency of surgery and hospital admissions for communicable diseases in a high- and middle-income setting. Br J Surg. 2015. August;102(9):1142–9. 10.1002/bjs.9845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weiser TG, Makary MA, Haynes AB, Dziekan G, Berry WR, Gawande AA; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Measurement and Study Groups. Standardised metrics for global surgical surveillance. Lancet. 2009. September 26;374(9695):1113–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61161-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]