Abstract

Objective:

To update the 2005 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guideline on corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

Methods:

We systematically reviewed the literature from January 2004 to July 2014 using the AAN classification scheme for therapeutic articles and predicated recommendations on the strength of the evidence.

Results:

Thirty-four studies met inclusion criteria.

Recommendations:

In children with DMD, prednisone should be offered for improving strength (Level B) and pulmonary function (Level B). Prednisone may be offered for improving timed motor function (Level C), reducing the need for scoliosis surgery (Level C), and delaying cardiomyopathy onset by 18 years of age (Level C). Deflazacort may be offered for improving strength and timed motor function and delaying age at loss of ambulation by 1.4–2.5 years (Level C). Deflazacort may be offered for improving pulmonary function, reducing the need for scoliosis surgery, delaying cardiomyopathy onset, and increasing survival at 5–15 years of follow-up (Level C for each). Deflazacort and prednisone may be equivalent in improving motor function (Level C). Prednisone may be associated with greater weight gain in the first years of treatment than deflazacort (Level C). Deflazacort may be associated with a greater risk of cataracts than prednisone (Level C). The preferred dosing regimen of prednisone is 0.75 mg/kg/d (Level B). Over 12 months, prednisone 10 mg/kg/weekend is equally effective (Level B), with no long-term data available. Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d is associated with significant risk of weight gain, hirsutism, and cushingoid appearance (Level B).

This document summarizes extensive information provided in the complete guideline, available as a data supplement on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org. Appendices e-1 through e-5, cited in this summary, are presented in the full guideline (data supplement). Tables e-1 through e-5 as well as references e1–e8, cited in this summary, are available at Neurology.org.

A 2005 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guideline on the use of corticosteroids in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) recommended prednisone or deflazacort in the treatment of DMD for short-term benefit in muscle strength and function.1 There are currently variations in practice in corticosteroid use.2

We address the following questions with regard to patients with DMD:

1. What is the efficacy of corticosteroids, specifically their effect on survival, quality of life (QoL), motor function, scoliosis, pulmonary function, and cardiac function?

2. What are the side effects of corticosteroid treatment?

3. How do prednisone and deflazacort compare in efficacy or side effect profile?

4. What is the optimal dosing regimen for corticosteroids?

5. Are there any useful interventions for maximizing bone health?

DESCRIPTION OF THE ANALYTIC PROCESS

The AAN Guideline Development Subcommittee convened a panel of experts on the treatment of DMD to develop this guideline update (appendices e-1 and e-2) following the AAN's 2004 process manual.3 We searched Medline for articles published from January 2004 through June 2012 (see appendix e-3 for the search strategy). We performed updated searches covering July 2012 through April 2013 and May 2013 through July 2014. We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and Science Citation Index, and references of selected articles and review articles.

We reviewed the titles and abstracts of the identified citations for relevance to the clinical questions and retrieved the full text of potentially relevant articles. We also included the Class I–III trials from the original guideline. We excluded trials with fewer than 10 patients. Two authors reviewed articles and completed data abstraction independently. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We rated studies for their risk of bias using the AAN 4-tiered classification of evidence scheme for therapeutic studies (appendix e-4). We linked the strength of practice recommendations to the strength of evidence (appendix e-5).

ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE

Our searches identified 757 citations. We reviewed the full text of 121 potentially relevant articles. Sixty-three fulfilled the inclusion criteria, of which 24 were graded Class I–III. Table e-1 describes the selected studies on corticosteroids, and table e-2 lists the selected studies on bone health interventions.

What is the efficacy of corticosteroids, specifically their effect on survival, QoL, motor function, scoliosis, pulmonary function, and cardiac function?

Do corticosteroids have an effect on survival?

Four Class III studies addressed this question. One study did not show significant survival differences but lacked precision to detect differences.4 In another study, 5% of those treated with deflazacort died in their second decade vs 35% of those who were untreated (relative rate [RR] 0.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.03–0.59).5 In a third study, mortality was higher in the untreated group (21%) than in the deflazacort-treated group (3%) after a mean follow-up period of 14.9 years and 15.5 years, respectively (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02–1.28).6 In a fourth study, mortality was higher in the untreated group (43%) than in the deflazacort- or prednisone-treated group (11%) after a mean follow-up of 11.3 years (RR 3.91, 95% CI 1.69–9.06).7

Conclusions.

In patients with DMD, deflazacort possibly increases survival over 5–15 years of treatment (3 Class III studies). There is insufficient evidence to support or refute the benefit of prednisone on survival in patients with DMD (1 Class III study using both prednisone and deflazacort and 1 negative underpowered study).

Do corticosteroids have an effect on QoL?

A single Class III study considered this question, but a Class III study alone is unable to support recommendations.8 The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

Is there an effect on motor function with corticosteroids compared with no treatment?

Two Class II and 14 Class III studies addressed this question. A Class II study compared prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d with placebo (table e-3).9 Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d was started at an average age of 9.16 years. At 6 months, muscle strength scores on a 10-point averaged muscle scale improved significantly over 34 muscle groups for both doses of prednisone vs placebo (p < 0.0001, 95% CI could not be calculated). Both treatment groups also improved in timed motor function, such as time to stand, compared with placebo (placebo 6.17 seconds, prednisone 0.75 mg/kg 4.15 seconds, prednisone 1.5 mg/kg 3.43 seconds, mean difference 2.74 seconds, p = 0.0001, 95% CI could not be calculated). Time to stand is an early, sensitive marker of weakness and disease progression, and this difference could be considered clinically significant.10

In a Class II study, prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d was compared with prednisone 0.3 mg/kg/d and with placebo (table e-4). Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d was started at a mean age of 9.36 years (SD 2.86). At 6 months, average muscle strength favored the use of prednisone over placebo (0.75 mg/kg 6.00, p = 0.0001; 0.3 mg/kg 5.82, p = 0.0001; placebo 5.48).11

Of the 14 Class III studies, 5 using deflazacort 0.9–1 mg/kg/d5,12–15 and 1 using deflazacort 2 mg/d alternate day dosing16 showed an improvement in motor outcome using various measures: age at loss of ambulation,12,13,16 functional motor score,5,13–16 and muscle strength.15 The average difference in mean age at loss of ambulation was between 1.4 and 2.5 years in 3 studies. Two studies using both prednisone and deflazacort showed an improvement in age at loss of ambulation17 and functional motor score.18 The other studies were not relevant to making conclusions since higher-level evidence was available.

Conclusions.

In patients with DMD, prednisone 0.3–1.5 mg/kg/d probably improves strength (2 Class II studies) and possibly improves timed motor function (1 Class II study). In patients with DMD, deflazacort 0.9–1 mg/kg/d possibly improves strength, age at loss of ambulation by 1.4–2.5 years, and timed motor function (several Class III studies).

Do corticosteroids decrease the need for scoliosis surgery?

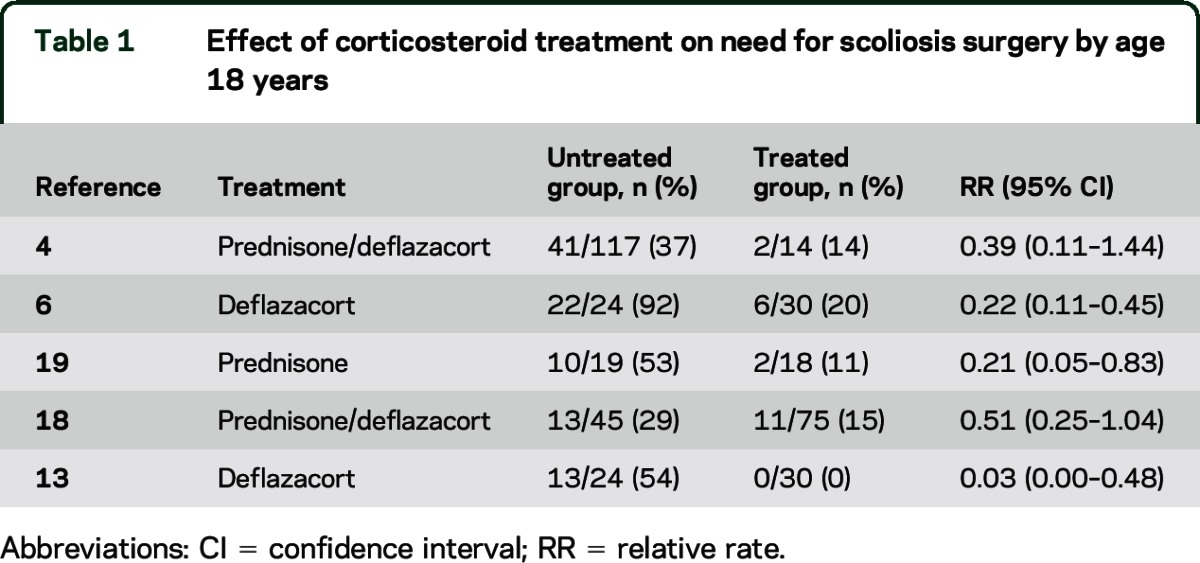

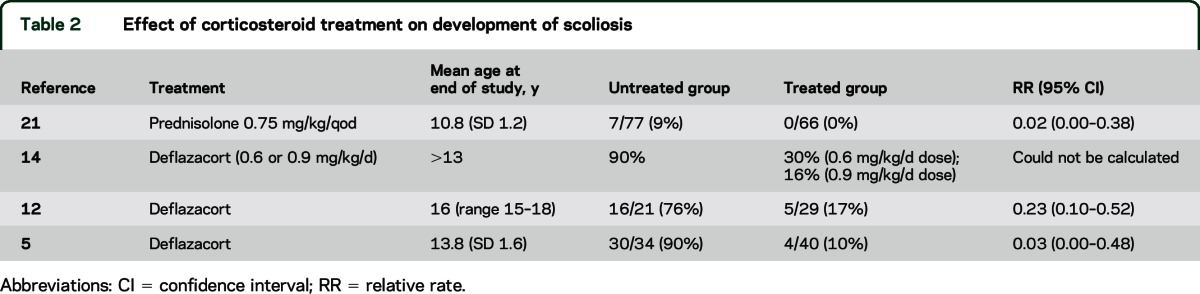

Ten Class III studies addressed this question. Five studies of deflazacort or prednisone showed less need for surgical correction by 18 years of age4,6,13,18,19 (table 1). Five studies showed delayed or slowed scoliosis development5,12,14,20,21 (table 2). One study did not provide data for RR calculation, but showed a delayed age at scoliosis onset with longer duration of prednisolone treatment (r = 0.44, p < 0.01).20

Table 1.

Effect of corticosteroid treatment on need for scoliosis surgery by age 18 years

Table 2.

Effect of corticosteroid treatment on development of scoliosis

Conclusion.

Corticosteroids (prednisone and deflazacort) possibly slow the development of scoliosis and reduce the need for scoliosis surgery by 18 years of age (10 Class III studies).

Do corticosteroids have an effect on pulmonary function?

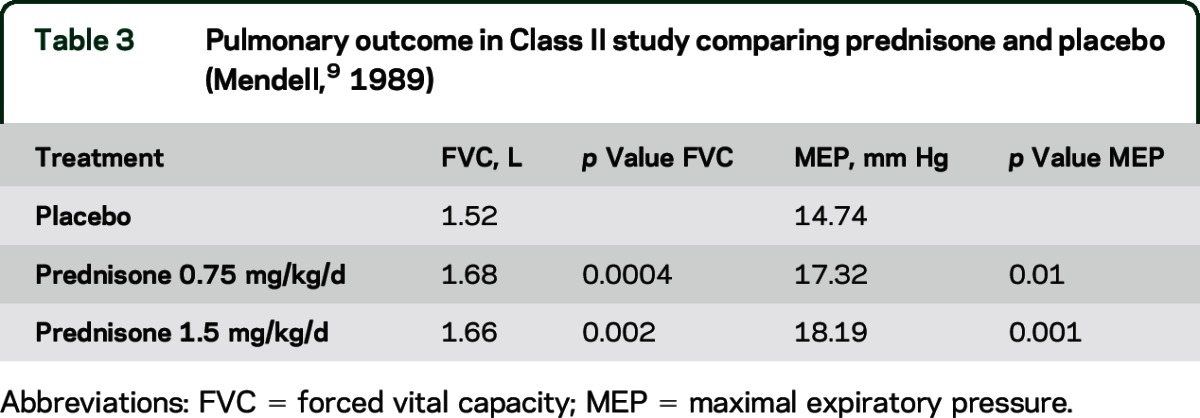

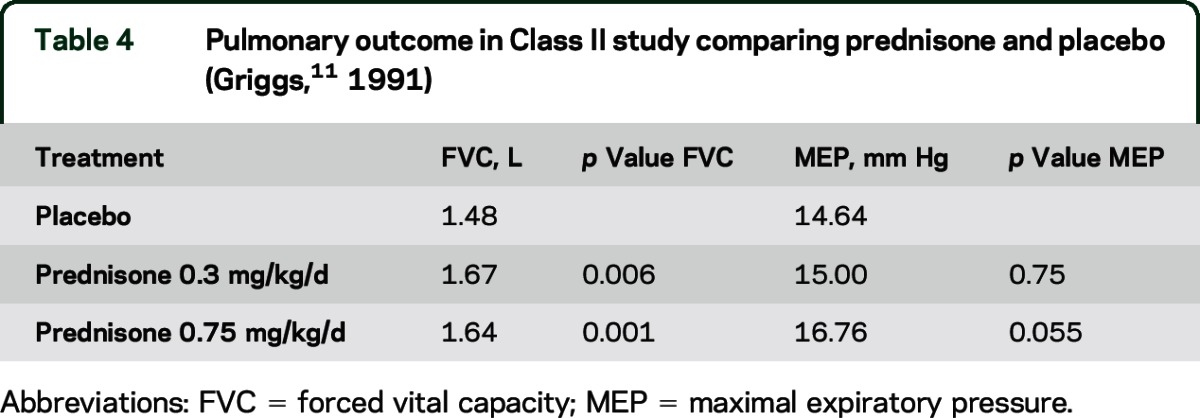

Two Class II and 12 Class III studies addressed this question. A Class II study of prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d compared with placebo over 6 months of treatment reported significant improvement in mean forced vital capacity (FVC) and maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) (table 3).9 Another Class II study noted significant improvement in FVC for both doses of prednisone (0.3 and 0.75 mg/kg/d) compared with placebo over 6 months of treatment but no significant difference in MEP (table 4).11 Neither study provided percent predicted values.

Table 3.

Pulmonary outcome in Class II study comparing prednisone and placebo (Mendell,9 1989)

Table 4.

Pulmonary outcome in Class II study comparing prednisone and placebo (Griggs,11 1991)

Twelve Class III studies using either deflazacort or prednisone showed benefit in various measures of pulmonary function.4–6,12,13,21–27

Conclusions.

In patients with DMD, prednisone probably improves pulmonary function as measured by FVC (2 Class II studies). In patients with DMD, deflazacort possibly improves pulmonary function (several Class III studies).

Do corticosteroids have an effect on cardiac function?

Shortening fraction (SF), a measure of left ventricular function,28 is often used to track progression of cardiomyopathy, a condition that affects almost all patients with DMD by age 18.29 Six Class III studies addressed this question. The first study showed that by 18 years of age, boys treated with deflazacort were less likely to have cardiomyopathy (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <45%) (4/40, 10%) than untreated boys (20/34, 59%) (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.06–0.45).5 A second study showed that boys treated with deflazacort or prednisone were less likely to have cardiomyopathy (%SF <28) (7/63, 11%) than untreated boys (14/23, 61%) (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.08–0.39).7 A third study found a later age at onset of cardiomyopathy (%SF <28) in treated boys (15.2 years, SD 3.4) than untreated boys (13.2 years, SD 4.8); for every year of corticosteroid treatment, cardiomyopathy onset was delayed by 4%.17 A fourth study showed a greater odds of developing cardiomyopathy in untreated boys (4.4 times greater in 3- to 10-year-olds and 15.2 times greater in 11- to 21-year-olds).30 The same authors later showed a hazard ratio of 0.15 for corticosteroid use in predicting cardiomyopathy in an age-adjusted model.31 Finally, the median LVEF was higher in boys 17–22 years old treated with deflazacort (53%, range 51%–57%) than in untreated boys 12–15 years old (48%, range 42%–51%) (p < 0.001).32

Conclusion.

In patients with DMD, corticosteroids (deflazacort 0.9 mg/kg/d or prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d) possibly delay the onset of cardiomyopathy (defined as %SF <28% or LVEF <45%) by 18 years of age (several Class III studies).

What are the side effects of corticosteroid treatment?

Two Class II studies9,11 and 22 Class III studies4–8,12–16,18,19,22–24,27,31,33–37 addressed this question, comparing corticosteroid side effects with those of no treatment or placebo. See table e-5 for the adverse events (AEs) seen in 2 Class II studies.

Conclusions.

In patients with DMD, corticosteroids probably have the AEs of short stature, behavioral changes, fractures, and cataracts (2 Class II studies). Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d is probably associated with significant risk of weight gain, hirsutism, and cushingoid appearance (2 Class II studies). Prednisone 0.3 mg/kg/d possibly has a lower incidence of these AEs (1 Class II study). Deflazacort possibly increases the risk of cataracts (3 Class III studies).

How do prednisone and deflazacort compare in efficacy or side effect profile?

Is there a significant difference in efficacy between prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and deflazacort 0.9 mg/kg/d?

Three Class III studies directly compared these 2 corticosteroids. In one study, deflazacort and prednisone were shown to have equally beneficial effects on functional motor outcomes, pulmonary function, and development of scoliosis over 5.49 years (SD 1.98).23 In another study, prednisone and deflazacort were equally effective in improving motor function and functional performance over a 12-month treatment period.18 A final study reported equivalent cardiac outcome in deflazacort- and prednisone-treated groups over a mean follow-up period of 3.0 years (SD 2.5).30

Conclusions.

Prednisone and deflazacort are possibly equally effective for improving motor function in patients with DMD (2 Class III studies). There is insufficient evidence to directly compare the effectiveness of prednisone vs deflazacort in cardiac function in patients with DMD (1 Class III study of a combined cohort).

Is there a significant difference in AEs between prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and deflazacort 0.9 mg/kg/d?

Two Class III studies addressed this question. The first study showed a difference in weight gain in the prednisone group during the first years of treatment, with no difference seen at later ages (12–15 years). At 10 years of age, their weights increased to the 75th and 90th percentiles, whereas the weights of the boys in the deflazacort group were similar to those of untreated boys at 10 years of age.23 Two boys in the deflazacort group (2/12, 17%) developed asymptomatic cataracts, whereas no boys (0/9) in the prednisone group reported cataracts (RR 3.8, 95% CI 0.21–70.23). In the other study, the prednisone group showed a greater weight gain in the first year of treatment than the deflazacort group.18 At 12 months of treatment, boys taking prednisone had a mean weight increase of 21.3%, compared with 9% in boys taking deflazacort (2.17 kg vs 5.08 kg weight increase, p < 0.05). An increase in body weight of more than 20% over baseline was seen in 1/9 (11%) boys taking deflazacort and in 4/8 (50%) boys taking prednisone (RR 4.5, 95% CI 0.63–32.38). Other AEs were not significantly different between the 2 groups, including behavioral changes, gastric symptoms, hypertension, glucose control, and hirsutism.

Conclusions.

Prednisone is possibly associated with greater weight gain in the first 12 months of treatment, with no significant difference in weight gain with longer-term use compared with deflazacort (2 Class III studies). Deflazacort is possibly associated with an increased risk of cataracts compared with prednisone, although most are not vision-impairing (2 Class III studies).

What is the optimal dosing regimen for corticosteroids?

Is there a preferred dose of deflazacort (0.6 mg/kg/d for the first 20 days of each month vs 0.9 mg/kg/d) with regard to efficacy or AEs?

A single Class III study considered this question, but a Class III study alone is unable to support recommendations.14 The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

Is there a difference in efficacy or AEs between prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 10 mg/kg/weekend?

A Class I trial evaluated prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d vs 10 mg/kg/weekend for the primary efficacy outcome of quantitative muscle testing (QMT) of the arm and leg. This study found similarities between groups in QMT of the arm (weekend 0.7, daily 1.3, 95% CI −1.7 to 0.6, with ±2 as the equivalent limit) and QMT of the leg (weekend 2.2, daily 2.1, 95% CI −1.8 to 2.0, with ±2 as the equivalent limit) over 12 months of treatment.38 Equivalency was noted for body mass index (weekend 17.8, daily 19.6, p = 0.12). No significant difference in other safety endpoints (weight, height, cataracts, lumbar spine z score by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, behavior) was noted.

Conclusions.

Prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 10 mg/kg/weekend probably provide equivalent benefit to patients with DMD at 12 months (1 Class I study). Prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 10 mg/kg/weekend probably have similar AE profiles over 12 months (1 Class I study).

Is there a difference in efficacy or AEs between prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d?

A Class II study comparing prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and prednisone 1.5 mg/kg/d with controls found no significant difference between the 2 groups with regard to strength or functional benefit at 6 months.9 No difference in AEs was seen between prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d.

Conclusions.

Prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d possibly provide equivalent benefit to patients with DMD, although smaller differences cannot be excluded (1 Class II study). Prednisone dosing regimens of 0.75 mg/kg/d and 1.5 mg/kg/d possibly have similar AE profiles (1 Class II study).

Is there a difference in efficacy or AEs between prednisone dosing regimens of 0.3 mg/kg/d and 0.75 mg/kg/d?

A Class II study compared prednisone 0.3 mg/kg/d and prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d and found a significant improvement in the group taking 0.75 mg/kg at 6 months (table e-4).11 A Class III study answered this question but will not be considered further since it is lower-level evidence.33

A Class II study showed an increase in the rate of cushingoid appearance and hirsutism at the 0.75 mg/kg/d dose compared with the 0.3 mg/kg/d dose (RR 1.79, 95% CI 1.11–2.88, and RR 4.53, 95% CI 1.43–14.32, respectively).11 The Class III extension study aiming to explore longer-term effects over an additional 12 months of follow-up showed a greater risk of hirsutism in the higher-dose prednisone group than in the lower-dose prednisone group (RR 4.42, 95% CI 1.70–11.46), with no significant difference in other AEs.33

Conclusions.

A prednisone dosing regimen of 0.75 mg/kg/d is possibly more efficacious than 0.3 mg/kg/d (1 Class II study). A prednisone dosing regimen of 0.75 mg/kg/d possibly has a greater rate of AEs than a regimen of 0.3 mg/kg/d (1 Class II study).

Is there a difference in efficacy or AEs between daily and alternate-day dosing of prednisone?

A single Class III study considered this question, but a Class III study alone is unable to support recommendations.39 The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

Is there a difference in efficacy or AEs between daily and intermittent dosing of prednisolone?

A single Class III study considered this question, but a Class III study alone is unable to support recommendations.36 The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

Are there any useful interventions for maximizing bone health?

One Class III study considered calcifediol40 and another Class III study considered bisphosphonates (alendronate),e1 but single Class III studies are unable to support recommendations. The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

Does treating bone health have an impact on survival?

A single Class III study considered this question, but a Class III study alone is unable to support recommendations.e2 The evidence is insufficient to make a determination.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinical context.

Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d has significant benefit in DMD management and should be considered the optimal prednisone dose. Prednisone 10 mg/kg/weekend is equally effective over a 12-month period, although long-term outcomes of this alternate regimen remain to be seen. Because of the expectation of significant AEs with corticosteroids, proper informed consent is required, and AEs should be discussed with patients and their families prior to therapy initiation and should be managed proactively. The American College of Rheumatology Task Force osteoporosis guideline recommends calcium and vitamin D supplementation for patients taking corticosteroids (any dose with an anticipated duration of ≥3 months) in order to maintain a total calcium intake of 1,200 mg/d and vitamin D intake of 800 IU/d through dietary sources and supplementation.e3

If a significant number of AEs develop, reducing the prednisone dose to 0.3 mg/kg/d may reduce the AE burden, albeit with less efficacy.

The AE profiles of deflazacort and prednisone vary slightly. Weight gain and cushingoid appearance may occur more frequently with prednisone than deflazacort, but cataracts are more frequently reported with deflazacort.

Recommendations.

Prednisone, offered as an intervention for patients with DMD:

Should be used to improve strength (Level B) and may be used to improve timed motor function (Level C)

Should be used to improve pulmonary function (Level B)

May be used to reduce the need for scoliosis surgery (Level C)

May be used to delay the onset of cardiomyopathy by 18 years of age (Level C)

Deflazacort, offered as an intervention for patients with DMD, may be used to:

Improve strength and timed motor function and delay the age at loss of ambulation by 1.4–2.5 years (Level C)

Improve pulmonary function (Level C)

Reduce the need for scoliosis surgery (Level C)

Delay the onset of cardiomyopathy by 18 years of age (Level C)

Increase survival at 5 and 15 years of follow-up (Level C)

Deflazacort and prednisone may be equivalent in improving motor function (Level C). There is insufficient evidence to establish a difference in effect on cardiac function (Level U). Prednisone may be associated with increased weight gain in the first years of treatment compared with deflazacort (Level C). Deflazacort may be associated with increased risk of cataracts compared with prednisone (Level C).

If patients with DMD are treated with prednisone, prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d should be the preferred dosing regimen (Level B). Prednisone 10 mg/kg/weekend is equally effective over 12 months, but long-term outcome is not yet established. Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d is probably associated with significant risk of weight gain, hirsutism, and cushingoid appearance (Level B), with equal side effect profile seen over 12 months with the 10 mg/kg/weekend dosing.

Prednisone 0.3 mg/kg/d may be used as an alternative dosing regimen with lesser efficacy and fewer AEs (Level C). Prednisone 1.5 mg/kg/d is another alternative regimen; it may be equivalent to 0.75 mg/kg/d but may be associated with more AEs (Level C).

Data are insufficient to support or refute the following (all Level U):

The addition of calcifediol and bisphosphonates (alendronate) as significant interventions for improving bone health in patients with DMD taking prednisone

A benefit of bisphosphonates for improving survival in patients with DMD taking corticosteroids

A benefit of prednisone for survival

A significant difference in efficacy or AE rates among daily, alternate day, and intermittent regimens for prednisone or prednisolone dosing

A preferred dose of deflazacort

An effect of corticosteroids on QoL

Suggestions for counseling.

The following suggestions for counseling are the opinion of the authors and extend from logical conclusions of our recommendations.

Patients with DMD and their families should:

Have a voice in the choice of the corticosteroid used, noting that the various corticosteroids differ in evidence supporting use, cost, availability, and AE profiles. When a corticosteroid has been agreed upon, a focused discussion of the risks particular to that corticosteroid should take place.

Be informed of the risks and benefits of adding a bisphosphonate to corticosteroid treatment.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

There is currently a paucity of high-quality data on the long-term efficacy of both prednisone and deflazacort. Many questions remain unanswered, including the following: When should treatment be initiated?e4 How long should patients remain on oral corticosteroid therapy? Is there an optimal dosing regimen, and does the dosing change (up, down, or stop) when patients lose ambulation or become ventilator dependent?e5 What are the long-term effects on bone health? There are anecdotal examples of patients with DMD who received treatment with corticosteroids from an early age remaining ambulatory.e6,e7 On the other hand, some negative effects of corticosteroids on bone health may be apparent only when patients lose ambulation.e8 There is a trial (NCT01603407) currently recruiting patients; we hope it will be able to answer some of these questions.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MEP

maximal expiratory pressure

- QMT

quantitative muscle testing

- QoL

quality of life

- RR

relative rate

- SF

shortening fraction

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Gloss: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. Dr. Moxley: study concept and design, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Ashwal: analysis or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Oskoui: acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. Authors who serve as AAN subcommittee members or methodologists (D.G., S.A., M.O.) were reimbursed by the AAN for expenses related to travel to subcommittee meetings where drafts of manuscripts were reviewed.

DISCLOSURE

D. Gloss serves as a paid evidence-based medicine consultant for the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). R. Moxley III has served as an editorial advisory board member of the Journal of the American Medical Association Clinical Trials Board; has received $2,500 in honoraria for an Isis Pharmaceuticals meeting (honoraria donated to the Abrams Family Fund for myotonic dystrophy research at the University of Rochester in Rochester, NY); and was awarded a 5-year National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant 2U54NS048843 (totaling $7,013,097), a 4-year US Food and Drug Administration grant 1R01FD003716 (totaling $1,510,125), and a National Cancer Institute contract HHSN2612012003188P (totaling $40,000). S. Ashwal has served on a medical advisory board for the Tuberous Sclerosis Association; has served as an associate editor for Pediatric Neurology; has a patent pending for use of HRS for imaging in stroke; is a coeditor of and has received royalties for Pediatric Neurology: Principles and Practice, 6th edition; has received grant funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke for use of advanced imaging for detecting neural stem cell migration after neonatal HII in a rat pup model; works in the Department of Pediatrics at Loma Linda University School of Medicine; and is called once yearly to act as a witness in legal proceedings as a treating physician for children with nonaccidental trauma. M. Oskoui has received travel funding from the AAN and Isis Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Isis Pharmaceuticals, Fonds de Recherché Santé (Québec, Canada), NeuroDevNet, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Canada), and McGill University Research Institute. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

DISCLAIMER

Clinical practice guidelines, practice advisories, systematic reviews, and other guidance published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and its affiliates are assessments of current scientific and clinical information provided as an educational service. The information (1) should not be considered inclusive of all proper treatments, methods of care, or as a statement of the standard of care; (2) is not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence (new evidence may emerge between the time information is developed and when it is published or read); (3) addresses only the question(s) specifically identified; (4) does not mandate any particular course of medical care; and (5) is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating provider, as the information does not account for individual variation among patients. In all cases, the selected course of action should be considered by the treating provider in the context of treating the individual patient. Use of the information is voluntary. The AAN provides this information on an “as is” basis and makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding the information. The AAN specifically disclaims any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use or purpose. The AAN assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of this information or for any errors or omissions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) is committed to producing independent, critical, and truthful clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). Significant efforts are made to minimize the potential for conflicts of interest to influence the recommendations of this CPG. To the extent possible, the AAN keeps separate those who have a financial stake in the success or failure of the products appraised in the CPGs and the developers of the guidelines. Conflict of interest forms were obtained from all authors and reviewed by an oversight committee prior to project initiation. The AAN limits the participation of authors with substantial conflicts of interest. The AAN forbids commercial participation in, or funding of, guideline projects. Drafts of the guideline have been reviewed by at least 3 AAN committees, a network of neurologists, Neurology peer reviewers, and representatives from related fields. The AAN Guideline Author Conflict of Interest Policy can be viewed at www.aan.com. For complete information on this process, access the 2004 AAN process manual.3

REFERENCES

- 1.Moxley RT, III, Ashwal S, Pandya S, et al. Practice parameter: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne dystrophy: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2005;64:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griggs RC, Herr BE, Reha A, et al. Corticosteroids in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: major variations in practice. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Neurology. Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual, 2004 ed St. Paul, MN: The American Academy of Neurology; 2004. Available at: https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/UnderDevelopment. Accessed February 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach JR, Martinez D, Saulat B. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the effect of glucocorticoids on ventilator use and ambulation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010;89:620–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biggar WD, Harris VA, Eliasoph L, Alman B. Long-term benefits of deflazacort treatment for boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in their second decade. Neuromuscul Disord 2006;16:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebel DE, Corston JA, McAdam LC, Biggar WD, Alman BA. Glucocorticoid treatment for the prevention of scoliosis in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schram G, Fournier A, Leduc H, et al. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes with prophylactic steroid therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beenakker EA, Fock JM, Van Tol MJ, et al. Intermittent prednisone therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Neurol 2005;62:128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendell JR, Moxley RT, Griggs RC, et al. Randomized, double-blind six-month trial of prednisone in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1592–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushby K, Connor E. Clinical outcome measures for trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report from International Working Group meetings. Clin Invest 2011;1:1217–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griggs RC, Moxley RT, III, Mendell JR, et al. Prednisone in Duchenne dystrophy: a randomized, controlled trial defining the time course and dose response: Clinical Investigation of Duchenne Dystrophy Group. Arch Neurol 1991;48:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alman BA, Raza SN, Biggar WD. Steroid treatment and the development of scoliosis in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:519–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biggar WD, Gingras M, Fehlings DL, Harris VA, Steele CA. Deflazacort treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pediatr 2001;138:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biggar WD, Politano L, Harris VA, et al. Deflazacort in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a comparison of two different protocols. Neuromuscul Disord 2004;14:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesa LE, Dubrovsky AL, Corderi J, Marco P, Flores D. Steroids in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: deflazacort trial. Neuromuscul Disord 1991;1:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angelini C, Pegoraro E, Turella E, Intino MT, Pini A, Costa C. Deflazacort in Duchenne dystrophy: study of long-term effect. Muscle Nerve 1994;17:386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber BJ, Andrews JG, Lu Z, et al. Oral corticosteroids and onset of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pediatr 2013;163:1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonifati MD, Ruzza G, Bonometto P, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial of deflazacort versus prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2000;23:1344–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bäckman E, Henriksson KG. Low-dose prednisolone treatment in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 1995;5:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinali M, Main M, Eliahoo J, et al. Predictive factors for the development of scoliosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2007;11:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilmaz O, Karaduman A, Topaloğlu H. Prednisolone therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy prolongs ambulation and prevents scoliosis. Eur J Neurol 2004;11:541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pradhan S, Ghosh D, Srivastava NK, et al. Prednisolone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy with imminent loss of ambulation. J Neurol 2006;253:1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balaban B, Matthews DJ, Clayton GH, Carry T. Corticosteroid treatment and functional improvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: long-term effect. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenichel GM, Florence JM, Pestronk A, et al. Long-term benefit from prednisone therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 1991;41:1874–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daftary AS, Crisanti M, Kalra M, Wong B, Amin R. Effect of long-term steroids on cough efficiency and respiratory muscle strength in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatrics 2007;119:e320–e324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henricson EK, Abresch RT, Cnaan A, et al. ; CINRG Investigators. The Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group Duchenne Natural History Study: glucocorticoid treatment preserves clinically meaningful functional milestones and reduces rate of disease progression as measured by manual muscle testing and other commonly used clinical trial outcome measures. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schara U, Mortier, Mortier W. Long-term steroid therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: positive results versus side effects. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2001;2:179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slama M, Maizel J. Echocardiographic measurement of ventricular function. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006;12:241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhodes J, Margossian R, Darras BT, et al. Safety and efficacy of carvedilol therapy for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markham LW, Spicer RL, Khoury PR, Wong BL, Mathews KD, Cripe LH. Steroid therapy and cardiac function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Cardiol 2005;26:768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markham LW, Kinnett K, Wong BL, Woodrow Benson D, Cripe LH. Corticosteroid treatment retards development of ventricular dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2008;18:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mavrogeni S, Papavasiliou A, Douskou M, Kolovou G, Papadopoulou E, Cokkinos DV. Effect of deflazacort on cardiac and sternocleidomastoid muscles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2009;13:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griggs RC, Moxley RT, III, Mendell JR, et al. Duchenne dystrophy: randomized, controlled trial of prednisone (18 months) and azathioprine (12 months). Neurology 1993;43:520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King WM, Ruttencutter R, Nagaraja HN, et al. Orthopedic outcomes of long-term daily corticosteroid treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2007;68:1607–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reitter B. Deflazacort vs. prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: trends of an ongoing study. Brain Dev 1995;17(suppl):39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricotti V, Ridout DA, Scott E, et al. ; NorthStar Clinical Network. Long-term benefits and adverse effects of intermittent versus daily glucocorticoids in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ten Dam K, de Groot IJ, Noordam C, van Alfen N, Hendriks JC, Sie LT. Normal height and weight in a series of ambulant Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients using the 10 day on/10 day off prednisone regimen. Neuromuscul Disord 2012;22:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escolar DM, Hache LP, Clemens PR, et al. Randomized, blinded trial of weekend vs daily prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2011;77:444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fenichel GM, Mendell JR, Moxley RT, III, et al. A comparison of daily and alternate-day prednisone therapy in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Neurol 1991;48:575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianchi ML, Morandi L, Andreucci E, Vai S, Frasunkiewicz J, Cottafava R. Low bone density and bone metabolism alterations in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: response to calcium and vitamin D treatment. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.