Sir,

Bronchiectasis (BXSIS) is characterized by non-reversible airway dilatation due to a variety of respiratory insults, and a few evidence-based medical therapies exist for the treatment of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis1. Acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis (AE-BXSIS) result in episodic worsening of lung function and symptoms2,3. Frequent exacerbations may accelerate decline in lung function and increase in mortality4. Goals of therapy in stable bronchiectasis include reduction in exacerbations and improvement in quality of life (QOL)3.

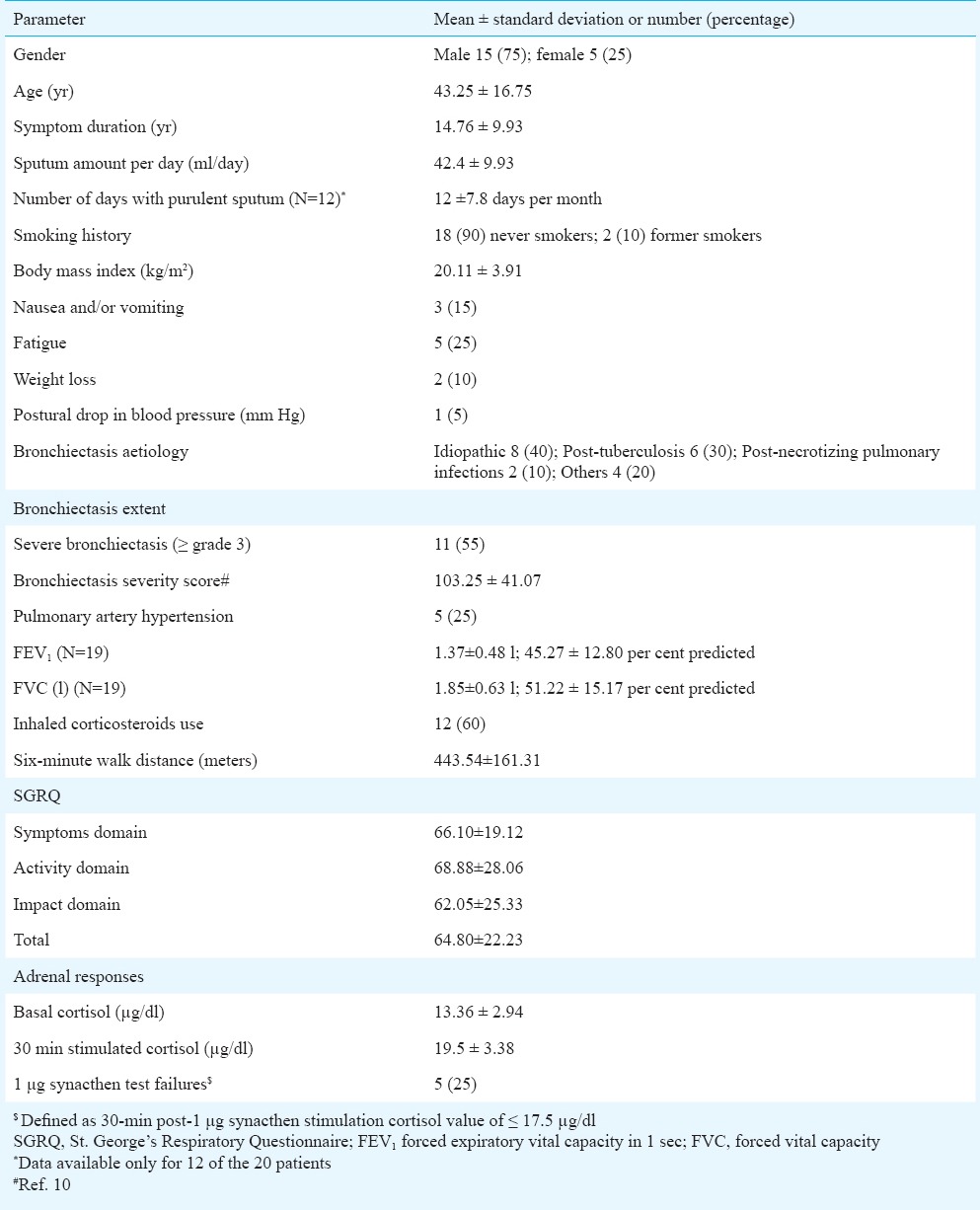

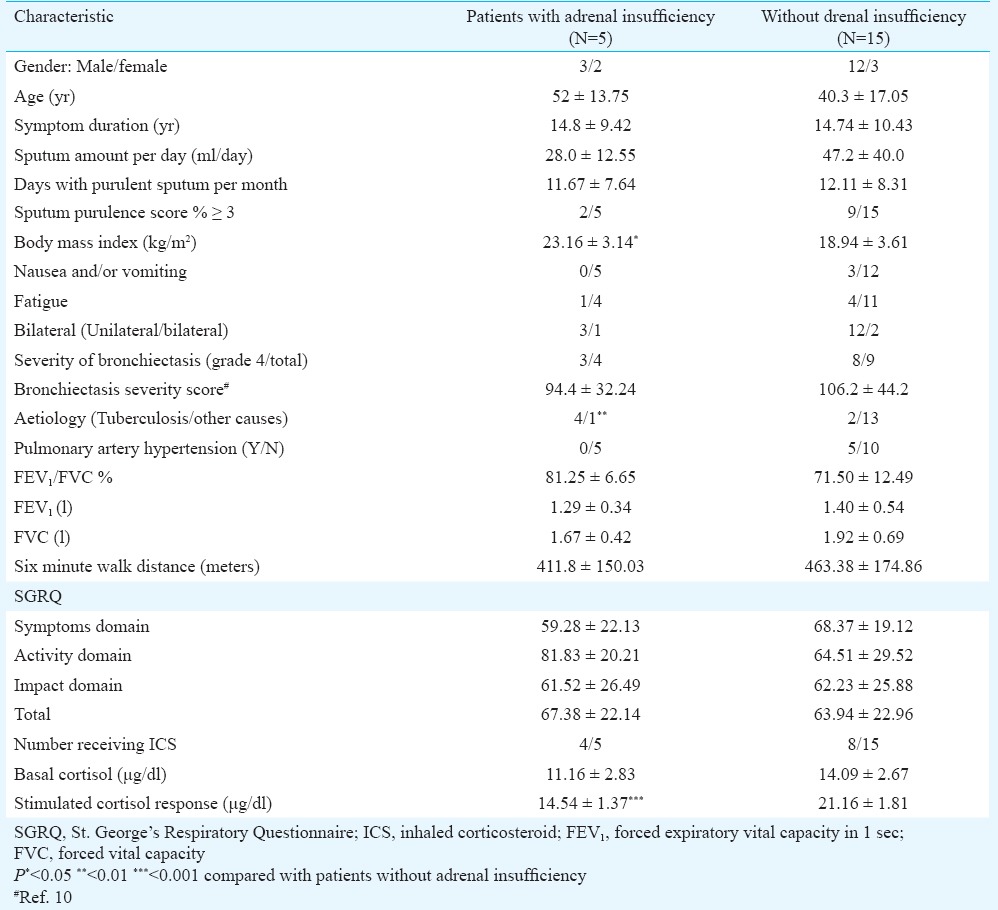

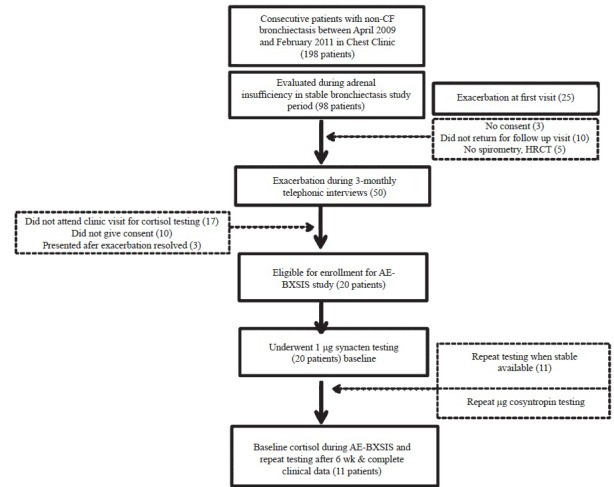

Patients with AE-BXSIS often experience increasing fatigue and expectoration, which significantly impair QOL and work capacity5. Increasing evidence suggests frequent adrenal insufficiency in stable bronchiectasis and correlates with symptoms and QOL as measured by the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)6. In a previous study, we found a similar prevalence of suppressed adrenal responses in patients from south India with stable bronchiectasis7. Little is known about adrenal responses during AE-BXSIS and relationship of these to longitudinal responses in stable state; also, the correlation of these responses with fatigue and QOL is unknown. We, therefore, conducted a pilot observational study at the St. John's Medical College Hospital, Bengaluru, India, between April 2009 and February 2012 to evaluate adrenal responses to 1 µg cosyntropin during AE-BXSIS and six weeks after resolution of AE-BXSIS. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics committee. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for bronchiectasis, study setting and methodology, reason for choice of 1 µg test and cut offs (≤17.5 μg/dl post-stimulation) have been described previously7. The aetiology of bronchiectasis was made based on clinical history and appropriate use of testing as per guidelines1,8. AE-BXSIS was defined as subjective and persistent (≥24 h) deterioration in at least four of the following nine parameters: fever (temperature greater than 37.5°C), cough, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, sputum purulence or volume, chest pain, respiratory signs on examination, radiographic signs and systemic symptoms3,9. The details of the enrolled patients are provided in Table I. Five patients (25%) failed to mount a positive response and fulfilled the criteria for adrenal insufficiency (post-stimulation cortisol ≤17.5 μg/dl). Basal cortisol values were not significantly different between patients with and without impaired adrenal reserve (IAR); 30-min post-stimulation values were significantly lower in patients with adrenal insufficiency (P=0.001). Tuberculosis as a cause of bronchiectasis was significantly associated with IAR [ P<0.01 (Fisher's Exact test) Table II].

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis (N=20)

Table II.

Comparison of characteristics between patients with and without relative adrenal insufficiency

Data on repeat testing of 1 µg synacthen was available in 11 of 20 patients (Figure). While there was a clear trend towards an increase in both basal (mean difference=2.59, P=0.14) and 30-minute cortisol values (mean difference=1.94, P=0.32), these values did not reach statistical significance. Using a cut-off of 17.5 µg/dl for IAR, 8 of 11 (72.7%) patients were classified the same way on repeat 1 µg synacthen testing. Two (18%) patients who were classified as normal during exacerbation had value suggestive of impaired adrenal reserve when re-tested during stable state and one had normal testing during stable state but failed to show incremental response during an exacerbation.

Figure.

Flowchart of the patients enrolled in the study of adrenal insufficiency in acute exacerbation of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.

The lack of association of basal values and AE-BXSIS is possibly because of heightened stress responses due to an exacerbation; however, a clear separation existed in 30-min stimulation values and this persisted after resolution of an exacerbation. A low 30-min cortisol response with active tuberculosis has been well documented11,12. Our previous study on stable bronchiectasis showed a correlation between SGRQ scores and IAR, but we did not find a correlation with post-tuberculosis aetiology and IAR in that study7. Repeat testing was performed in only 11 patients. Most of the patients remained in the same class, suggesting that the IAR might be a persistent abnormality rather than being specific for the acute phase. It is well known that there is significant variability on repeat testing in adrenal stimulation tests13. Two patients who were classified as normal during exacerbation were diagnosed to have IAR on repeat examination.

Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal HPA)-axis dysfunction could be a part of acute and/or chronic inflammatory disease because of its obvious therapeutic implications. Larger longitudinal studies with repeated examination of adrenal function in bronchiectasis both during acute exacerbation and in the stable phase are required for a better understanding of the contribution of HPA-axis to symptomatology, quality of life and mortality in bronchiectasis.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Dr P.J. Jones, for kindly providing permission to use the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire in English and local languages.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Pasteur MC, Bilton D, Hill AT British Thoracic Society Non-CF Bronchiectasis Guideline Group. British Thoracic Society guideline for non-CF bronchiectasis. Thorax. 2010;65:577. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.142778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell AE, Barker AF, Ilowite JS, Fick RB. Treatment of idiopathic bronchiectasis with aerosolized recombinant human DNase I. rhDNase Study Group. Chest. 1998;113:1329–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell AE. Bronchiectasis. Chest. 2008;134:815–23. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Garcia MA, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Perpina-Tordera M, Roman-Sanchez P, Soriano J. Factors associated with lung function decline in adult patients with stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Chest. 2007;132:1565–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gompertz S, O’Brien C, Bayley DL, Hill SL, Stockley RA. Changes in bronchial inflammation during acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1112–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.99114901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holme J, Tomlinson JW, Stockley RA, Stewart PM, Barlow N, Sullivan AL. Adrenal suppression in bronchiectasis and the impact of inhaled corticosteroids. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1047–52. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00016908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajagopala S, Ramakrishnan A, Bantwal G, Devaraj U, Swamy S, Ayyar SV, et al. Adrenal insufficiency in patients with stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:393–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, Webb SC, Foweraker JE, Coulden RA, et al. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1277–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9906120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker AF, Bardana EJ., Jr Bronchiectasis: update of an orphan disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:969–78. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch DA, Newell J, Hele V, Dyer D, Corkery K, Fox NL, et al. Correlation of CT findings with clinical evaluations in 261 patients with symptomiatic bronchiectasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:53–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.1.10397099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casanova-Cardiel LJ, Flores-Barrientos OI, Schabib-Hany M, Miranda-Ruiz R, Castanon-Gonzalez JA. Cosyntropin test in severe active tuberculosis. Cir Cir. 2008;76:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad GA, Sharma SK, Mohan A, Gupta N, Bajaj S, Saha PK, et al. Adrenocortical reserve and morphology in tuberculosis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2000;42:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azziz R, Bradley E, Jr, Huth J, Boots LR, Parker CR, Jr, Zacur HA. Acute adrenocorticotropin-(1-24) (ACTH) adrenal stimulation in eumenorrheic women: reproducibility and effect of ACTH dose, subject weight, and sampling time. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:1273–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-5-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]