Abstract

Context:

Pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases (AD) is one of a multifactorial milieu. A genetic predisposition, an immune system failure, hormonal imbalance and environmental factors play important roles. Among the many environmental factors, the role of infection is gaining importance in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune disorders; among them, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) plays a pivotal role. Literature states an association of various AD with EBV namely multiple sclerosis, autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematous, oral lichen planus (OLP), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), autoimmune hepatitis, Sjögren's syndrome and Kawasaki disease; among these, the most commonly occurring are OLP and RA.

Aim:

Considering the frequency of occurrences, our aim was to perform a qualitative analysis of EBV viral capsid antigen (EBV VCA) IgG in the sera of patients with RA, OLP and establish a comparison with normal.

Settings and Design:

In-vitro experiment in a research laboratory.

Subjects and Methods:

Five-milliliter blood sample was collected from 25 patients diagnosed with RA and OLP. Serum was separated and EBV VCA IgG antibody titer was detected using NovaTec EBV VCA IgG ELISA kit.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi-square test.

Results:

Six out of 25 subjects with RA and 4 out of 25 subjects with OLP tested positive for EBV VCA IgG.

Conclusions:

Both environmental and genetic factors are important contributory components for autoimmune conditions. Screening for viral etiology would improve the efficacy of conventional treatment and reduce the risk of relapses.

Keywords: ELISA, Epstein–Barr virus, oral lichen planus, rheumatoid arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Epstein –Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous herpesvirus that is, named after “Michael Anthony Epstein,” which causes acute infectious mononucleosis. It has an established association with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, Burkitt lymphoma and other lympho-proliferative disorders in immunocompromised individuals.[1] EBV is a polyclonal activator; B cells are stimulated to produce immunoglobulins along with rheumatoid factors. Antibodies are produced against early antigens (EA), viral capsid antigen (VCA) and Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen.[2] According to the serological profiles, VCA-IgG antibodies are present during acute and chronic primary infections, past infections and reactivation.

Oral lichen planus (OLP), a premalignant disorder, is a mucocutaneous disease affecting 0.5–1% of the world population, the etiology of which is unknown. It affects females with a ratio of 1.4:1; it predominantly occurs in adults older than 40 years. The proposed hypothesis in literature explains it as a T cell mediated autoimmune disease (AD) in which cytotoxic CD8+ T cells trigger the apoptosis of oral epithelial cells. The CD8+ lesional T cells may recognize an antigen associated with the major histocompatibility complex class 1 on keratinocytes. After antigen recognition and activation, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells may trigger keratinocyte apoptosis.[3] In spite of the above-suggested pathway, the possible antigen responsible for inducing OLP is still unclear although the role of viruses is being proposed as a major etiological factor.[4] Tobacco chewing, smoking and alcohol consumption are predisposing factors for premalignant transformation of lichen planus.[5] However, some authors believe that the role of EBV in OLP and its malignant transformation is still controversial. We therefore hypothesized that EBV in combination with chemical agents may be involved in the etiology of OLP.

We also considered rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic autoimmune condition, that is very commonly seen among females at an older age with a 0.5% worldwide prevalence.[6] The cause of RA still is unclear though it has been understood from previous studies that both genetic and environmental factors play an important contributing role toward disease inclination, the former accounts for about one-half of the risk.[7] The involvement of EBV in RA has been speculated for several years now. Literature review suggests that patients with RA have a peculiarly increased frequency of circulating EBV-infected B cells; this phenomenon could be explained by the defective control of infected B cells by EBV-specific T cells. Studies done by Fox et al. have shown increased titers of antibodies to EBV antigens in patients with RA.[8] A few other studies have also shown higher viral loads of EBV in patients with advanced RA.[9] A link between EBV and RA has been established over years mainly due to the reduced immune regulation that is evident in patients with RA.

We therefore conducted a small-scale study to qualitatively specify the presence of EBV VCA IgG in patients with OLP and RA.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Sample collection

A case–control study was conducted; 25 patients diagnosed with RA and OLP of the age group in the range of 30–50 years were recruited from the inpatient Department of Rheumatology and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Healthy controls were obtained from the teaching and the nonteaching staff. After obtaining informed consent approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee, 2 mL of peripheral blood was collected, centrifuged at 3500 rpm and the serum was stored at − 20°C.

Principle and procedure

The NovaTec EBV VCA IgG antibody ELISA test kit was used which is designed for the qualitative detection of specific IgG antibodies against EBV VCA in serum and plasma of the patients.

The NovaTec EBV VCA IgG antibody test kit is based on the principle of the enzyme immunoassay. Microtiter strip wells were precoated with EBV antigens to bind corresponding antibodies of the specimen. The wells were washed to remove all unbound sample material and horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-human IgG conjugate was added which bound to the captured EBV-specific antibodies. The immune complex formed by the bound conjugate was visualized by adding tetramethylbenzidine substrate which gave a blue reaction product. To stop the reaction, sulfuric acid was added which produced a yellow endpoint color. Absorbance at 450 nm was read using an ELISA microwell plate reader.

RESULTS

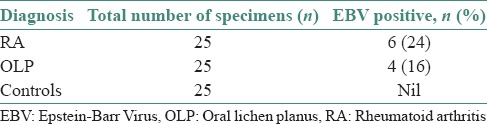

The virological data of the OLP and RA patients were analyzed by using the Chi-square test. Results are depicted in Table 1. Out of 25 OLP cases analyzed, four showed positivity for EBV VCA IgG. Of 25 RA patients, six significantly showed EBV VCA IgG positivity compared to control subjects with (P < 0.0005). Our cases who tested positive were all females with a mean age of (52.56 years) for RA and (35.36 years) for OLP. The positivity for EBV VCA IgG in four cases of OLP and six cases of RA indicate that all had been previously infected with EBV and at present, showed either the replication or reactivation status of the virus. Both OLP and RA cases associated with EBV did not show any difference clinically when compared to patients diagnosed without EBV association. Histological assessment was not performed. The study was carried out based on clinical diagnosis only. As this was purely a cross-sectional study to screen patients with OLP and RA, we could not assess the prognosis of patients; further large-scale studies and long-term follow-ups are required.

Table 1.

Summary of EBV status in OLP, RA and control groups

DISCUSSION

On discussing the various pathogenesis of autoimmunity, environmental factors should be considered as one of the major contributing reasons for the development of ADs. Of all, the most common environmental factor is the role of infection by a microbial agent. It has been briefly described that the four main mechanisms by which infection can lead to ADs are molecular mimicry; second, a phenomenon known as “epitope spreading,” third refers to polyclonal activation and the fourth mechanism is known as “Bystander activation,” where there is an expansion of autoreactive T cells which is induced due to the enhanced cytokine production.[10]

EBV infection until date has been the most well-established relationship between a viral infection and the development of an AD. The results of the present study depict a statistically significant positivity for EBV VCA IgG in the peripheral blood of patients with RA and OLP, thereby indicating a previous infection with EBV and that no primary infection is present. The positivity, especially for EBV VCA IgG primarily also indicates that the cases demonstrate either reactivation or replication of EBV.

Recent studies have suggested that EBV has evolved to transform host immune responses by encoding a homolog of human interleukin 10 (IL-10), known as viral IL-10 in its sequence. It suppresses T helper 1 responses; this property assists in maintaining viral infections by damping down T cell immunity. Such effects would be expected to be beneficial in RA by suppressing cell-mediated processes.[7] Various other studies have also suggested that EBV may induce the production of anti-CCP, which are highly specific of RA.[11] It has also been suggested by various authors that EBV modulates IL-6 production by the synovial membrane and induces the production of metalloproteases and tumor necrosis factor -α by infected B cells.[7] Another study confirms that sera from patients with RA contained higher titer antibodies to latent and replicative EBV antigens such as EBVNA, VCA and EA. On comparing with the literature, our study demonstrated positivity among females with a mean age of 52.56 years in RA patients.[6]

Until date, almost all of the 8 recognized human herpesviruses (HHVs) may give rise to oral lesions and 4 among them, such EBV, herpes simplex virus 1, HHV-6 and cytomegalovirus have been implicated in OLP.[12] Studies using nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been performed earlier and have found that 50% of OLP samples tested positive for EBV DNA. A higher optometric density IgG anti-EA antibody levels in OLP patients than in controls has also been reported. EBV positivity in OLP in some studies could be due to decrease in the immune resistance, locally or generally. In comparison to the above-mentioned studies, our study also reports 16% cases of OLP to show EBV VCA IgG positivity with female predominance and a mean age of 35.36 years, suggesting a past EBV infection or reactivation in EBV-positive OLP lesions. However, there is an existing dilemma, whether EBV infection is the prime causative agent in the pathogenesis of OLP, or it is secondary to the local immunosuppression that sets in due to the OLP lesions. We presume that immunosuppression in patients with OLP triggers the activation and replication of the EBV viruses; this phenomenon may be responsible for the progression of the disease. With the knowledge of published data, it has been understood that EBV along with chemical agents (tobacco and alcohol) may be involved in the pathogenesis of OLP.[5] The premalignant potential of OLP is controversial; EBV in combination with tobacco and alcohol consumption may be the supreme factors responsible for its malignant transformation. Horiuchi et al.[13] proposed three theories for the presence of EBV DNA in oral premalignant and malignant lesions: (1) EBV easily infects oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells, (2) EBV infection may be involved in the carcinogenesis of oral squamous cell epithelium and (3) EBV exists in cancer cells as a passenger.

A positive association of EBV to the premalignant potential of OLP has been documented in earlier studies; 100% EBV positivity was observed in OSCC patients.[14] PCR study performed by Horiuchi et al.[13] demonstrated positivity of EBV genomes in approximately one-half of the patients affected with SCC. Sand et al.[5] demonstrated high EBV prevalence in OLP and OSCC cases. In accordance to our study results and previously published data (Pedersen's theory), we suggest an EBV infection in EBV-positive OLP lesions. Not much data are available on the direct role of EBV in the pathogenesis of OLP and its malignant transformation to OSCC. Prospective cohort studies should be performed which focus on a long-term follow-up of OLP patients positive for EBV, to assess its malignant potential.

Although the present study suggests an association between the presence of EBV and autoimmune conditions, the data obtained do not support a direct role for EBV and autoimmune conditions. The role of EBV in RA and OLP is unclear and may differ for each. EBV has different immune modulation abilities on people from different genetic backgrounds, which could lead to EBV-associated diseases, rather than a result of a direct pathogenic effect of EBV gene products.[15]

Lodi et al.[16] carried out a systematic review on the various treatment modalities being used for patients diagnosed with OLP. The primary goal is to reduce the pain associated with OLP lesions. At present, the following therapies have been evaluated for treating symptomatic OLP cases: Topical corticosteroids includes clobetasol, betamethasone, dexamethasone and triamcinolone; topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) such as tacrolimus, pimecrolimus; retinoid such as tretinoin; photochemotherapy, photodynamic therapy[17] and traditional medicines (aloe vera gels and curcuminoids). In EBV-associated OLP lesions, treatment regimen should be modified by supplementing mainly with antioxidants and immunomodulatory drugs which could help overcome immunosuppression. Randomized control trials (Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy) performed by Salazar-Sánchez et al.[18] focused on improvising the immunosuppression in patients by applying 0.4 mL aloe vera gel in the mouth, 3 times in a day for 12 weeks. Studies performed by Xu et al.[19] combined prednisolone 5–10 mg along with Vitamin C and herbal decoction which synergistically provided relief to patients with symptomatic OLP and prevented severe immunosuppression. Use of western medicine such as TCIs should be eliminated as it plays a role in malignant transformation; the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a “black box” warning regarding the use of steroids.[16]

CONCLUSION

Considering the results of the present study, the malignant potential of OLP and the disease severity of RA;, we suggest that EBV screening and detection should be followed as a mandatory protocol for patients diagnosed with OLP and RA. Patient's positive with EBV can be treated with antiviral therapies along with conventional treatment modalities. A combination of the above measures would help in combating the disease progression and improvise patient life span.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butel J. General properties of viruses. In: Carrol KC, editor. Jawetz, Melnick, and Adelberg's Medical Microbiology. 26th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2013. pp. 407–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venables P. Epstein-Barr virus infection and autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:265–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajendran R. Diseases of skin. In: Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam B, editors. Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology. 6th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 799–803. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahenjamee M, Eslami M, Jahanzad I, Babaee M, Kharazani TN. Presence of Epstein – Barr virus in oral lichen planus and normal oral mucosa. Iran J Public Health. 2007;36:92–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sand LP, Jalouli J, Larsson PA, Hirsch JM, Angelholm G. Prevalence of Epstein – Barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral lichen planus, and normal oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:586–92. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.124462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balandraud N, Roudier J, Roudier C. Epstein-Barr virus and rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ollier W. Rheumatoid arthritis and Epstein-Barr virus: A case of living with the enemy? Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:497–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.7.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox RI, Luppi M, Pisa P, Kang HI. Potential role of Epstein-Barr virus in Sjögren's syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1992;32:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonneville M, Scotet E, Peyrat MA, Saulquin X, Houssaint E. Epstein-Barr virus and rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Rhum. 1998;65:365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoenfeld Y, Zandman-Goddard G, Stojanovich L, Cutolo M, Amital H, Levy Y, et al. The mosaic of autoimmunity: Hormonal and environmental factors involved in autoimmune diseases-2008. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toussirot E, Roudier J. Pathophysiological links between rheumatoid arthritis and the Epstein-Barr virus: An update. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horiuchi K, Mishima K, Ichijima K, Sugimura M, Ishida T, Kirita T. Epstein-Barr virus in the proliferative diseases of squamous epithelium in the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz I, Van Den Brule AJ, Brink AA, Snijders PJ, Walboomers JM, Van Der Waal I, et al. No direct role for Epstein-Barr virus in oral carcinogenesis: A study at the DNA, RNA and protein levels. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:356–61. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000501)86:3<356::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen MR. Epstein – Barr virus, the immune system, and associated diseases. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodi G, Carrozzo M, Furness S, Thongprasom K. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Br Assoc Dermatologists. 2012;166:938–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostafa D, Tarakji B. Photodynamic therapy in treatment of oral lichen planus. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:393–9. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2147w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salazar-Sánchez N, López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Sánchez-Siles M. Efficacy of topical Aloe vera in patients with oral lichen planus: A randomized double-blind study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:735–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu YZ, Geng Y, Liu YX, Fuan YQ, Liu J. Clinical study on three-step treatment of oral lichen planus by integrated traditional and western medicine. J Mod Stomatol. 2002;16:344–6. [Google Scholar]