Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Oral cancer constitutes 3% of all neoplasms and is the eighth most frequent cancer in the world. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) corresponds to 95% of all oral cancers. It is associated with severe morbidity, recurrence and reduced survival rates. Its prognosis is affected by several clinicopathologic factors, one of which is perineural invasion (PNI). It is the third most common form of tumor spread exhibited by neurotropic malignancies that correlate with aggressive behavior, disease recurrence and increased morbidity and mortality. In this retrospective study, our aim was to assess the presence of PNI in different grades of both primary and recurrent cases of OSCC correlating it with tumor size and lymph node status. The various patterns of PNI we encountered were also noted.

Materials and Methods:

PNI was assessed in 117 cases of primary and recurrent cases of OSCC. PNI was correlated with tumor thickness, lymph node status and with the different histologic grades. Location of PNI, density of PNI and various patterns of PNI were also assessed.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square test.

Results:

Our study showed that 47 out of 117 patients (40.5%) showed PNI. Both primary and recurrent tumors showed PNI of 42.50% and 40.50%, respectively. PNI was present in 34 out of 69 cases (49.3%) of clinically positive nodes. Around 79% of the nerves involved by PNI were intratumoral in location, 80% of the cases showed PNI density of 1–3 nerves per section and incomplete and/or “crescent-like” encirclement was the most common pattern of PNI noted in our study.

Conclusion:

Our study showed that the incidence of PNI was as high as 40% in OSCC. PNI was present in both primary and recurrent tumors, irrespective of its histologic grading. Tumor thickness and lymph node status correlated well with PNI. Therefore, the presence of PNI should be checked in every surgical specimen with OSCC as it gives significant prognostic value, influences treatment decisions, recurrence and distant metastasis. The presence of PNI necessitates more aggressive resection, coincident management of neck lymph nodes and the addition of adjuvant therapy. Also, targeted drug therapy for this type of tumor spread can open up new avenues in the treatment of OSCC.

Keywords: Growth patterns, histological grading, Oral squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, primary and recurrent tumors, tumor-node-metastases staging

INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer constitutes 3% of all neoplasms and is the eighth most frequent cancer in the world. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) corresponds to 95% of all oral cancers.[1]

OSCC is associated with severe morbidity, recurrence and reduced survival rates. Its prognosis is affected by several clinicopathologic factors, one of which is perineural invasion (PNI). It is a form of tumor spread exhibited by neurotropic malignancies that correlate with aggressive behavior, disease recurrence and increased morbidity and mortality. PNI is due to tropism of tumor cells for nerve bundles in the surrounding stroma.[2] Incidence of PNI in head and neck cancer is as high as 80%.[3]

PNI has not been given its due importance as it is not accounted for in the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/International Union Against Cancer (UICC) staging system. A detailed appraisal of various factors might be the need of the hour to improve the morbidity and mortality of oral cancer.

In this retrospective study, our aim was to assess the presence of PNI in primary and recurrent cases of OSCC and thereby correlating it with tumor thickness and nodal status. In addition, the presence of PNI in different histologic grades of OSCC, location, density and pattern of PNI most frequently encountered were also noted in our study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens

A retrospective, in vitro study approved by the Ethical Committee with a sample size of 117 cases of OSCC was considered. The study samples were obtained from the archives of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology and a cancer hospital. Both primary and recurrent tumors were considered for the study.

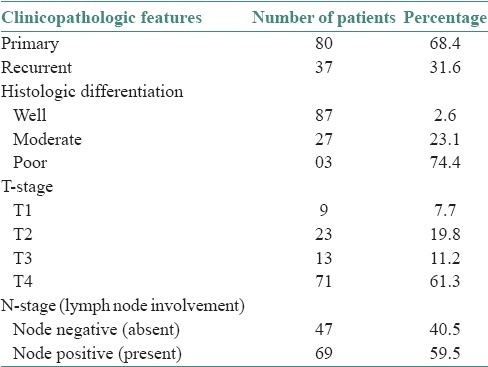

Data regarding the tumor-node-metastases (TNM) staging were obtained. Tumors were staged retrospectively according to TNM staging proposed by UICC. No patient had an evidence of distant metastasis at the time of initial examination. The clinicopathologic features have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic characteristics of 117 patients

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections cut from paraffin-embedded tumor specimens were assessed. Tumors were graded as well, moderate and poor based on the degree of keratinization, nuclear pleomorphism and number of mitoses [P4]. Eighty-seven (74.4%) patients’ tumors were well-differentiated, 27 (23.1%) were moderately differentiated and 3 (2.6%) were poorly differentiated. 80 (68.4%) patients had primary tumors and 37 (31.6%) patients had recurrent tumors. The clinicopathologic features were then correlated with PNI.

The sections were examined for the presence of PNI. Various parameters such as location of PNI, number of nerves involved per section (PNI density) and patterns of PNI were also assessed.

PNI was considered present when tumor cells were identified in the perineural space or epineurium. Tumor cells not entering the perineural space, but present just adjacent to the nerve were not considered as PNI.[4]

Location of PNI and PNI density were assessed according to the criteria specified by Miller et al. For every focus of PNI identified, distance to tumor edge (in millimeters) was assessed. A positive value indicated extratumoral (ET) location and a negative value indicated an intratumoral (IT) location. Location was arbitrarily assigned as peripheral if the focus of PNI was located 0–0.2 mm from the tumor edge.[5]

The density of PNI for each case was calculated by counting the number of PNI foci per tissue section. They were broadly subcategorized as 1–3 nerves/section and >3 nerves per section.

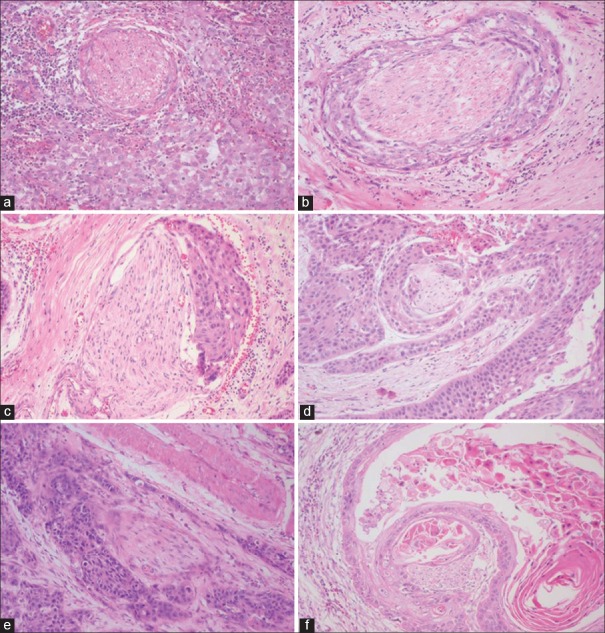

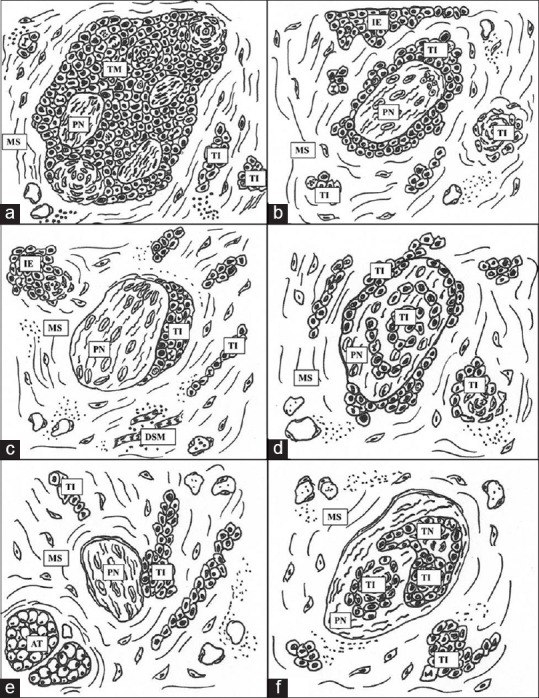

Various patterns of PNI were observed such as complete encirclement, incomplete “crescent-like” encirclement, sandwiching “onion skin,” partial invasion and neural permeation [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Hand drawn illustration of patterns and location of perineural invasion. (a) Complete encirclement, intratumoral location (b) complete encirclement (c) incomplete “crescent-like” encirclement, peripheral location (d) sandwiching “onion skin” (e) partial invasion, extratumoral location (f) neural permeation. Abbreviations: PN: Peripheral nerve, TI: Tumor island, MS: Mesenchymal stroma, TM: Tumor mass, IE: Invasive edge, TN: Tumor necrosis, DSM: Degenerating skeletal muscle, AT: Adipose tissue

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing various patterns of perineural invasion. (a) Intratumoral complete encirclement (b) complete encirclement (c) incomplete “crescent-like” encirclement (d) sandwiching “onion skin” (e) partial invasion (f) neural permeation (H&E stain, ×10)

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

The data accumulated were analyzed and the following points were noted.

Forty-seven (40.5%) out of the hundred and seventeen patients showed PNI and seventy patients showed no evidence of PNI histopathologically. The relationships between PNI and clinicopathologic factors have been summarized in the following graphs.

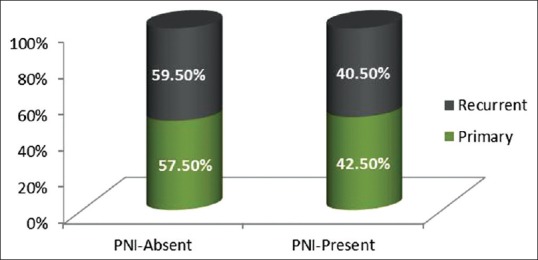

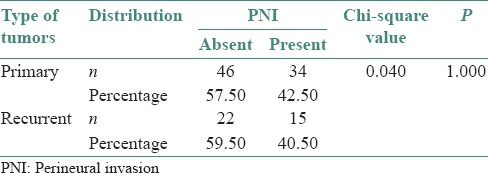

Thirty-four (42.5%) out of 80 patients with primary OSCC and fifteen (40.5%) out of thirty seven patients with recurrent tumors showed PNI [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Graph depicting distribution of perineural invasion in primary and recurrent oral squamous cell carcinoma

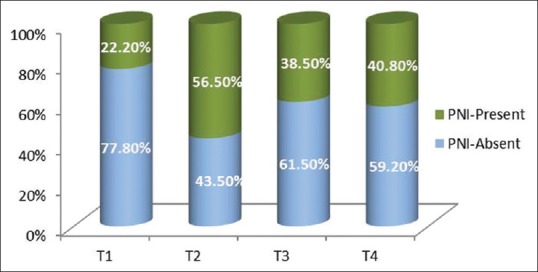

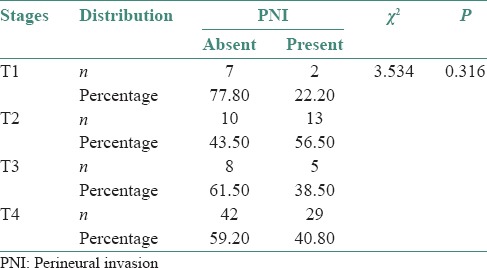

Two (22.2%) out of 7 cases in T1 stage, thirteen (56.5%) cases in T2 stage, 5 (38.5%) cases in T3 stage and twenty nine (40.8%) out of forty two cases in T4 stage showed PNI [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Graph depicting relationship of perineural invasion with the tumor thickness

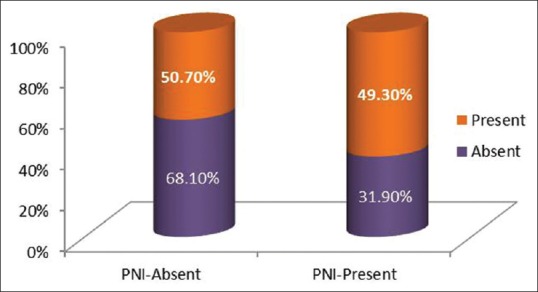

PNI was present in fifteen out of forty seven cases (31.9%) of clinically negative nodes whereas PNI was present in thirty four out of sixty nine cases (49.3%) of clinically positive nodes [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Graph depicting relationship of perineural invasion with the nodal status

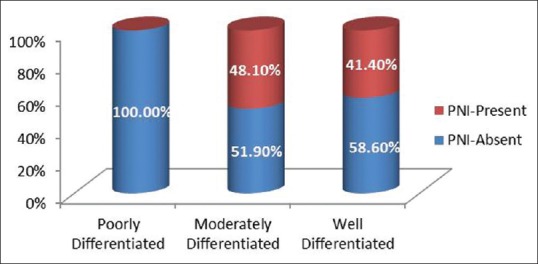

Thirty-six (41.4%) out of 87 patients having well differentiated OSCC and thirteen (48.10%) out of twenty seven patients having moderately differentiated OSCC had PNI [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Graph depicting distribution of perineural invasion in different grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma

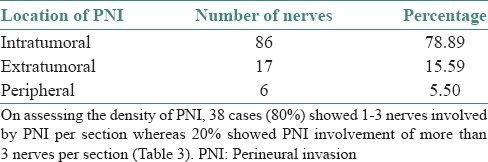

PNI was present in 109 nerves in forty seven cases of OSCC, which were assessed in our study. 78.89% of nerves were IT in location followed by ET and peripheral with percentage of 15.59% and 5.50%, respectively [Figures 1a, c and e and Table 2].

Table 2.

Number and percentage of cases showing location of perineural invasion

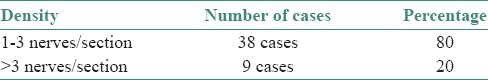

On assessing the density of PNI, 38 cases (80%) showed 1-3 nerves involved by PNI per section whereas 20% showed PNI involvement of more than 3 nerves per section [Table 3].

Table 3.

Number and percentage of cases showing perineural invasion density

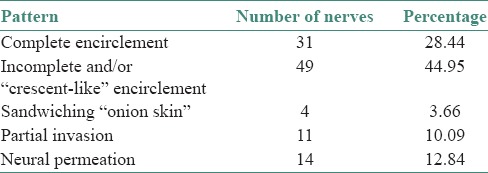

The different patterns of PNI observed were complete encirclement including intratumoral encirclement (28.44%), incomplete and/or “crescent-like” encirclement (44.95%), sandwiching “onion skin” (3.66%), partial invasion (10.09%) and neural permeation (12.84%) [Table 4], [Figures 1a–f and 2a–f].

Table 4.

Number and percentage of cases showing the various patterns of perineural invasion

DISCUSSION

Oral cancer has been discussed extensively in the literature, accounting for 3% of all neoplasms and is the eighth most common cancer in the world. OSCC corresponds to 95% of all oral cancers. Prognosis of OSCC is affected by many clinicopathologic factors.[1] Various parameters such as invasive edge, stromal component, inflammatory response, and tissue eosinophilia correlate with OSCC to provide better prognostic results. PNI is one such factor, which has definite bearing upon the prognosis.

Histologic evidence of PNI is known to be a poor prognostic factor and indicative of the need for adjuvant therapy.

Works of Ballantune et al. in the 19th century and Batsakis in the 20th century on PNI have given increased value to its clinical importance.[5]

PNI is a distinct pathologic entity that can be observed in the absence of lymphatic or vascular invasion. It can be the source of distant tumor spread or may be the sole route of metastatic spread.[3]

Various definitions have been proposed for PNI. Batsakis (1985) gave a broad definition of PNI as tumor cell invasion in, around and through the nerves. Liebig et al. in addition to the definition of Batsakis added “tumor in close proximity to nerve and involving at least 33% of its circumference or tumor cells within any of the 3 layers of the nerve sheath.”[3] We considered PNI as positive on finding tumor cells in the perineural space or epineurium.

Our study showed that the occurrence of PNI was as high as 40.5%.

In our study, both primary and recurrent tumors showed PNI [Table 5]. The presence of PNI is significantly related to recurrence of tumors and there is a trend for increased incidence of recurrence with the presence of PNI.[4]

Table 5.

Distribution of perineural invasion in primary and recurrent cases of squamous cell carcinoma using Chi-square test

Of the 117 cases of OSCC patients, 71 patients were in T4 stage and 46 patients were in T1, T2 and T3 stages, respectively. 40.8% of patients in T4 stage showed PNI histopathologically [Table 6]. Though the percentage positivity was highest in T2 stage, followed by T4, T3 and T1, sample size was small in these groups to be considered. PNI correlates well with the tumor thickness.

Table 6.

Distribution of perineural invasion in relation to tumor size of squamous cell carcinoma using Chi-square test

According to Liao et al. PNI is an independent risk factor with 5-year overall survival in pT4 N0 patients.[6]

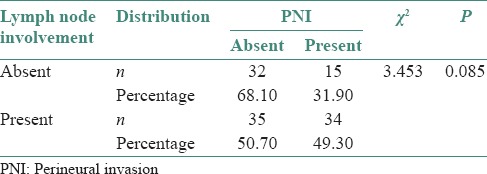

PNI was present in 15 out of 47 cases (31.9%) of clinically negative nodes whereas PNI was present in 34 out of 69 cases (49.3%) of clinically positive nodes [Table 7]. Such an occurrence of PNI can be an indicator for elective neck dissection even in those nodes which are clinically negative.

Table 7.

Distribution of perineural invasion in lymph node involvement in squamous cell carcinoma cases using Chi-square test

Prognosis and, therefore, treatment decisions are largely dependent on TNM staging, as determined by clinical examination, imaging and histopathologic characteristics in the biopsy which affect patient outcome. The presence of PNI is one such histopathologic feature. Most of the investigations have shown that PNI is associated with disease recurrence, increased probability of regional and distant metastasis and an overall decreased 5-year survival rate in noncutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[2,5]

PNI was present in 41.4% and 48.10% of well and moderately differentiated OSCC, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant which emphasizes the fact that PNI can be present even in well-differentiated tumors. The presence of PNI can be an indicator of aggressive clinical behavior even in well-differentiated OSCC where generally, the prognosis is considered to be good. Thus, the presence of PNI is irrespective of the histologic grade.

Location of foci of PNI was assessed, categorized as ET, IT and peripheral. Most of the nerves involved showed an IT location, followed by ET and peripheral.

The number of nerves involved by PNI per section when assessed showed that 80% of cases showed PNI density of 1–3 nerves per section in our study.

Many growth patterns were observed in our study: Complete encirclement, incomplete “crescent-like” encirclement, sandwiching “onion skin,” partial invasion and neural permeation. Among these, complete and incomplete encirclement were the most common patterns as observed by Rahima et al. In our study, incomplete and/or crescent-like encirclement was the most common pattern noted [Table 4].

Some of the pitfalls of the current AJCC/UICC staging system is the lack of recognition of prognostic factors such as PNI, lymphatic and vascular invasion, morphology (exophytic vs. endophytic), tumor host interface (infiltrative vs. pushing margins) under the “T” category in head and neck carcinomas.[7] Reporting of PNI in OSCC is not considered in the current AJCC/UICC system. It is implemented in the cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas in the seventh edition of AJCC/UICC where PNI is considered as one of the “high-risk features” in the “T” category independent of tumor size.[8]

It is a core item in the National Clinical Guidelines and a site-specific item in the Cancer Outcomes and Services Datase (COSD). PNI into the skull base is one specific determinant for stage pT4 in AJCC. PNI correlates with a high risk of local recurrence and high clinical morbidity.[9]

Assessment of PNI status in OSCC is a required component of pathologic analysis according to reporting protocols published by the College of American Pathologists.[10]

The presence or absence of PNI at the advancing tumor front must be recorded according to The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia.[11]

The presence of PNI has also been shown to mark late stage disease and one of the factors used to make a decision about adjuvant radiotherapy so that a subgroup of node-negative patients are benefited. Authors even suggest the need for elective neck dissection in PNI-positive node negative tumors.[5]

PNI represents the third mode of metastatic spread along with lymphatic and vascular invasion, but it has not been extensively studied. Recent studies on neurotrophic factors such nerve growth factor (NGF), adhesion molecules such as N-CAM, ICAM-5 (Telencephalon), tight junction molecule Claudin-1 and extracellular matrix proteins such as Laminin 5 have been associated with increased PNI in OSCC.[2] Among these, the neurotrophins such as NGF are considered potential factors facilitating PNI. NGF which is responsible for development, maintenance and function of vertebrate nervous system exerts its effects through binding to TrKA, p75NTR and sortilin receptors. Overexpression of NGF or TrK is significantly associated with clinicopathologic parameters such as positive PNI, larger tumor size, higher clinical stage and decreased survival rates.

Shen et al. have studied the immunohistochemical expression of NGF in oral tongue squamous cell carcinomas and have confirmed the above findings.[12]

Understanding the mechanism of its progression, the various molecular events that promote PNI in OSCC can pave way to the development of therapeutic agents that target this form of tumor spread.

Thus, histologic assessment of PNI and its uniform reporting in OSCC is vital adding value to the quality of life of patient in many patients to dictate prognosis and treatment protocol.

CONCLUSIONS

PNI is present in both primary and recurrent tumors, irrespective of its histologic grading.

The presence of PNI should be checked in every surgical specimen with OSCC as it gives significant prognostic value and influences recurrence and distant metastasis.

The presence of PNI necessitates more aggressive resection, coincident management of neck lymph nodes and the addition of adjuvant therapy.

There can be scope for targeted drug therapy for PNI in OSCC in the coming years.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Matos FR, Lima ED, Queiroz LM, da Silveira EJ. Analysis of inflammatory infiltrate, perineural invasion, and risk score can indicate concurrent metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1703–10. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binmadi NO, Basile JR. Perineural invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A discussion of significance and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1005–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, Berger DH, Albo D. Perineural invasion in cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer. 2009;115:3379–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahima B, Shingaki S, Nagata M, Chikara S. Prognostic significance of perineural invasion in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2004;97:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller ME, Palla B, Chen Q, Elashoff DA, Abemayor E, St John MA, et al. A novel classification system for perineural invasion in noncutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Histologic subcategories and patient outcomes. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:212–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao CT, Chang JT, Wang HM, Ng SH, Hsueh C, Lee LY, et al. Survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: Differences between pT4 N0 and other stage IVA categories. Cancer. 2007;110:564–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagheri SC, Bell B, Khan LA. Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1st ed. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. 7th ed. Chicago: Springer; 2010. Summary of Changes; Understanding the Changes from the Sixth to the Seventh Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; pp. 299–344. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater D, Walsh M. 1st ed. London: Royal College of Pathologists; 2014. Standards and datasets for reporting cancers dataset for the histological reporting of primary invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and regional lymph nodes. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilch BZ, Gillies E, Houck JR, Min KW, Novis D, Shah J, et al. Upper Aerodigestive tract Cancer Protocols and Checklist. Northfield, Ill: College of American Pathologists; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jane Dahlstrom, Hedley Coleman, Newell Johnson, Elizabeth Salisbury, Michael Veness, et al. Oral Cancer Structured Reporting Protocol. 1st ed. New South Wales (Australia): The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen W, Wang Y, Chang JY, Yu S, Chen H, Chiang C, et al. NGF expression in tongue cancers. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:258–64. doi: 10.1111/jop.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]