Abstract

S100A8 and S100A9 are calcium-binding proteins that are secreted primarily by granulocytes and monocytes, and are upregulated during the inflammatory response. S100A8 and S100A9 have been identified to be expressed by epithelial cells involved in malignancy. In the present study, the transcriptional levels of S100A8 and S100A9 were investigated in various subtypes of breast cancer (BC), and the correlation with estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) gene expression was evaluated using microarray datasets. The expression of S100A8 and S100A9 in BC cells was assessed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The regulation of ESR1 and GATA3 by administration of recombinant S100A8/A9 was examined in the BC MCF-7 cell line using quantitative (q)PCR. The association between S100A8 and S100A9 and overall survival (OS) was investigated in GeneChip® data of BC. The expression levels of S100A8 and S100A9 were higher in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2)-amplified and basal-like BC. The messenger (m)RNA levels of S100A8 and S100A9 were inversely correlated with ESR1 and GATA3 expression. S100A8/A9 induced a 10-fold decrease in the mRNA levels of ESR1 in MCF-7 cells. Poor OS was associated with high expression levels of S100A9, but not with high expression levels of S100A8 in BC. In conclusion, strong expression and secretion of S100A8/A9 may be associated with the loss of estrogen receptor in BC, and may be involved in the poor prognosis of Her2+/basal-like subtypes of BC.

Keywords: breast cancer, S100A8, S100A9, estrogen receptor 1, GATA binding protein 3

Introduction

S100A8 and S100A9 are calcium-binding proteins that are secreted primarily by granulocytes and monocytes (1). Although S100A8 and S100A9 are able to form homodimers, they typically exhibit pro- and anti-inflammatory properties (2) by forming heterodimers of S100A8/A9, alternatively known as calprotectin (3,4). High serum levels of S100A8/A9 correlate with inflammatory response in a number of chronic diseases, including rheumatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and atherosclerosis (5). S100A8/A9 is proposed to be a sensitive biomarker for monitoring inflammatory activities (6). Circulating levels of S100A8/A9 have additionally been identified to be elevated in several tumors, including lung, colon, gastric and breast cancer (BC), and may contribute to cancer cell survival and metastasis (7).

BC may be classified into several molecular subtypes based on gene expression profiles (8). The estrogen receptor (ER)+ subtypes, known as luminal A and luminal B, are the most predominant molecular subtypes of BC (8). ER+ BC, which represents ~70% of all BC cases, presents good prognosis and a better response to endocrine therapies than ER− BC (9). Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2)-amplified and basal-like BC subgroups constitute the ER− subtypes (8). Other less characterized molecular subtypes, including normal breast-like and claudin-low BC, have additionally been categorized as ER− BC in certain studies (10). Evidence from previous studies strongly suggests that the molecular subtype influences the systemic therapy and clinical outcome of BC (11). Her2-amplified BC accounts for ~20–25% of all invasive BC cases, and presents a poor overall survival (OS) rate (12). However, following the development of drugs such as trastuzumab, which selectively targets Her2, an improved prognosis may be achieved for this subtype of BC (12). Basal-like BC accounts for ~10% of all BC cases, and presents the worst prognosis, as there is currently no available endocrine or targeted therapy for this subtype of BC (13).

In BC, S100A8/A9 has been suggested to be a potential candidate for the mediation of metastasis of breast epithelial cells (14). S100A8/A9 is additionally able to promote the invasion of BC cells by binding to its receptor, known as receptor for advanced glycation end-product (RAGE), on the surface of cancer cells (15). However, the molecular mechanisms by which S100A8/A9 participates in the regulation of BC survival remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, the expression of S100A8 and S100A9 was investigated in various subtypes of BC, and its secretion by BC cells was evaluated. The present study additionally analyzed the correlation between S100A8/A9 expression and the expression of other genes, including GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) and estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), using GeneChip® data for BC. The effects of the recombinant protein S100A8/A9 on the regulation of GATA3 and ESR1 gene expression were assessed in the MCF-7 human ER+ BC cell line. The transcriptional levels of S100A8 and S100A9 and their association with the prognosis of BC were examined using microarray data.

Materials and methods

Microarrays

In the present study, published BC microarray data from a Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI) cohort was analyzed (16). NKI data were generated using the Affymetrix® platform (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The gene expression profiling and clinical data of the NKI cohort may be downloaded from http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/experiment/html/cancerdata.html. In summary, the NKI dataset contains data measured in 25,000 spot oligonucleotide arrays obtained from 295 cases of BC. All patients were <53 years old and exhibited lymph node-negative stage I or II disease.

Cell culture

The MCF-7 BC cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

For investigation of the effects of S100A8/A9 on gene expression, including ESR1 and GATA3, 1×106 MCF-7 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA, USA) and treated with 10 ng/ml human recombinant S100A8/A9 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 24 h.

S100A8/A9 expression was additionally investigated in breast tumor tissue samples. Breast tumor tissue was obtained from a 53-year-old patient, who underwent a modified radical mastectomy at the Second Hospital of Jiaxing (Jiaxing, China) following a diagnosis of stage I invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast. Samples of size 0.5×0.5 cm were disected from breast tumors and adjacent normal tissue, and were stored in liquid nitrogen within half an hour of removal.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells using TRIzol® reagent purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The RNA samples were treated with 1 µl DNase (5 U/µl; Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). A total of l µg RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed to complementary (c)DNA in a final volume of 20 µl using a ReverTra Ace® quantitative (q)PCR RT kit (Toyobo Co., Ltd.). A total of 1 µl of each cDNA sample was subsequently amplified in a PCR mixture with DNA polymerase (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) in a final volume of 25 µl. Human β-actin was utilized as a reference gene. The sequences of the primers used in the reaction are shown in Table I. Primers were designed using Primer Express® software version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The primers were synthesized by Invitrogen™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Negative controls (no cDNA and no reverse transcriptase) were run in parallel.

Table I.

Primers for reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| S100A8 | |

| Forward | TGTCTCTTGTCAGCTGTCTTTCA |

| Reverse | CCTGTAGACGGCATGGAAAT |

| S100A9 | |

| Forward | GGAATTCAAAGAGCTGGTGC |

| Reverse | TCAGCATGATGAACTCCTCG |

| β-actin | |

| Forward | GTGGCATCCACGAAACTACCTT |

| Reverse | GGACTCGTCATACTCCTGCTTG |

The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: PCR was performed on a thermal cycler (ABI Veriti®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by a specific number of cycles (S100A8 and S100A9, 32 cycles; β-actin, 25 cycles) consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 20 sec, annealing at the specified temperature for 25 sec, and extension at 72°C for 50 sec. A final extension step was conducted at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated using a 1% agarose gel (Gene Company Ltd., Hong Kong, China) with a 100 bp DNA ladder (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) stained with GelRed™ (Biotium, Inc., Hayward, CA, USA). Image Lab™ version 3.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used for densitometry analysis of the DNA gels.

qPCR

Relative messenger (m)RNA levels were quantified using qPCR with Applied Biosystems® StepOnePlus™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Primers were designed using Primer Express® Software. The sequences of the primers used are presented in Table II. PCR amplification was performed in duplicate using 96-well plates (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SYBR® Green RealTime PCR Master Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The mRNA levels of human β-actin were measured in an identical manner, and served as the reference gene. All samples were normalized to β-actin values, and the results are expressed as fold-changes of Cq value relative to the control using the 2−ΔΔCq formula (17).

Table II.

Primers for quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| S100A8 | |

| Forward | ATTTCCATGCCGTCTACAGG |

| Reverse | TGCCACGCCCATCTTTATCA |

| S100A9 | |

| Forward | CACCCAGACACCCTGAACCA |

| Reverse | CCTCGAAGCTCAGCTGCTTG |

| Estrogen receptor 1 | |

| Forward | CCTGATGATTGGTCTCGTCTG |

| Reverse | GGCACACAAACTCCTCTCC |

| GATA binding protein 3 | |

| Forward | ACAAAATGAACGGACAGA |

| Reverse | GTGGTGGTCTGACAGTTC |

| β-actin | |

| Forward | GGATGCAGAAGGAGATCACTG |

| Reverse | CGATCCACACGGAGTACTTG |

Serum analyses

Cultured MCF-7 cell medium was collected following two days of incubation, and frozen at −20°C. The concentration of S100A8/9 in the medium was measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cusabio Biotech Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. Differences between means were analyzed using Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance. For the purpose of studying correlations, Pearson's correlation coefficient was determined using univariate Cox regression analysis. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to analyze survival, and the P-value was calculated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) method. The graphical representation of the data and the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression patterns of S100A8 and S100A9 differ in various subtypes of BC

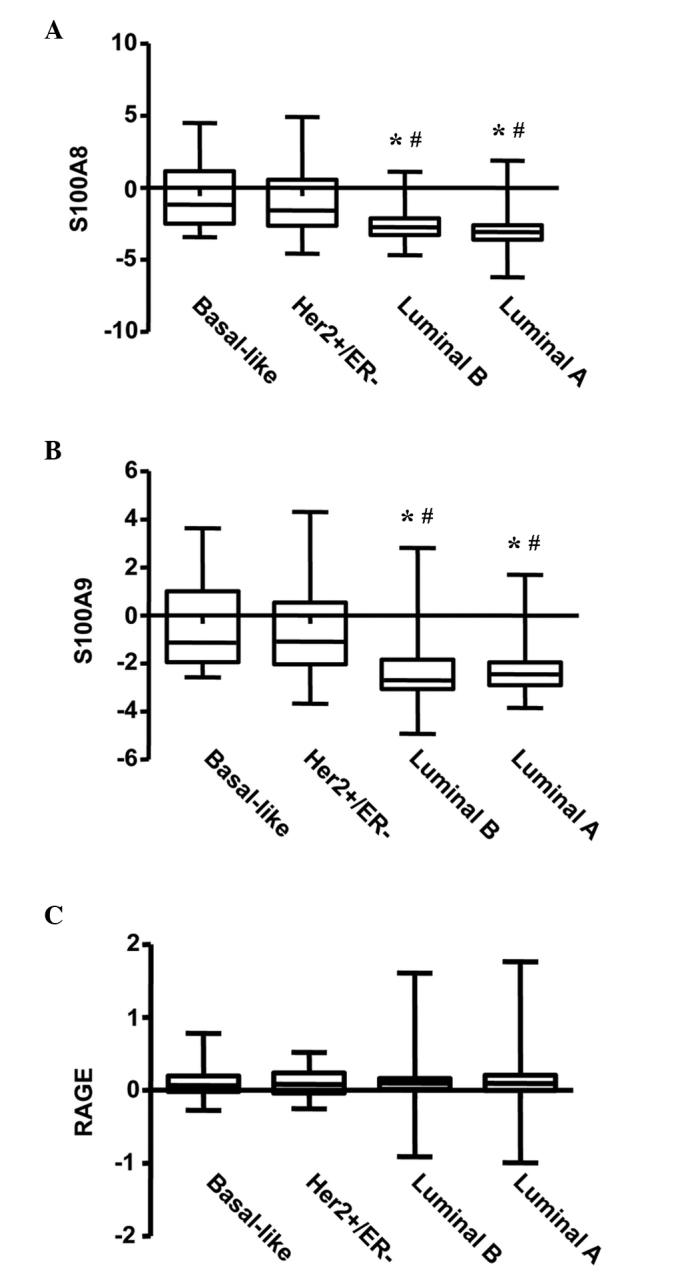

Initially, the present study investigated the transcriptional levels of S100A8 and S100A9 in various subtypes of BC using the NKI BC cohort. A significant difference in the transcriptional levels of S100A8 was observed among the four subgroups of BC, with increased expression of S100A8 in the basal-like and Her2-amplified subgroups, and lower expression in the luminal A and B subtypes (P<0.001; Fig. 1A). A similar expression pattern was observed for S100A9 (P<0.001; Fig. 1B). However, no difference was observed for the expression levels of RAGE (the S100A8/A9 receptor) in the four subgroups of BC (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Analysis of S100A8, S100A9 and RAGE gene expression in various subtypes of breast cancer using the Netherlands Cancer Institute cohort. The mRNA levels of (A) S100A8 and (B) S100A9 were higher in Her2+/basal-like breast cancer, and the difference was significant among the four groups (P<0.0001) *P<0.05, the difference between the basal-like and Luminal B and Luminal A groups; #P<0.05 the difference between Her2+/ER− group and Luminal B and Luminal A groups. (C) The mRNA levels of RAGE did not exhibit a significant difference among the four groups (P>0.05). The results are presented as the mean ± standard error. RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end-product; mRNA, messenger RNA; Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ER, estrogen receptor.

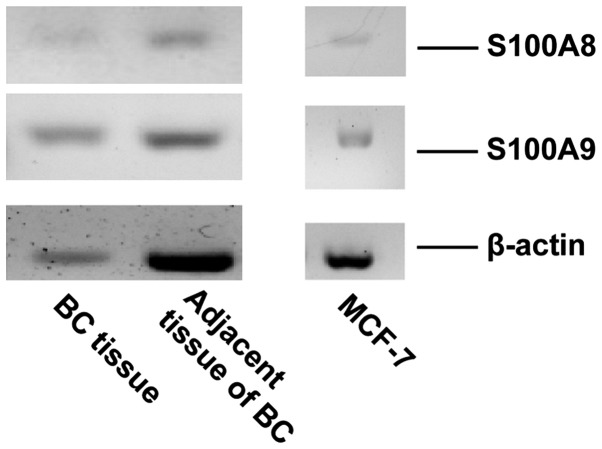

S100A8/A9 is expressed and secreted by BC cells

RT-PCR was performed to evaluate the gene expression of S100A8 and S100A9 in MCF-7 cells and breast tumor tissue. Signals corresponding to S100A8 and S100A9 were detected in MCF-7 cells and in breast tumor tissue (Fig. 2). ELISA was performed to detect the secretion of S100A8/A9 in the medium of the cultured MCF-7 cells. The concentration of S100A8/A9 was ~7.18 ng/ml in the medium of cultured MCF-7 cells following two days of incubation (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Expression of S100A8 and S100A9 in BC tissue and the MCF-7 BC cell line. S100A8 and S100A9 messenger RNA signals were detected in BC tissue, adjacent tissue and MCF-7 cells using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. β-actin was utilized as a reference gene. BC, breast cancer.

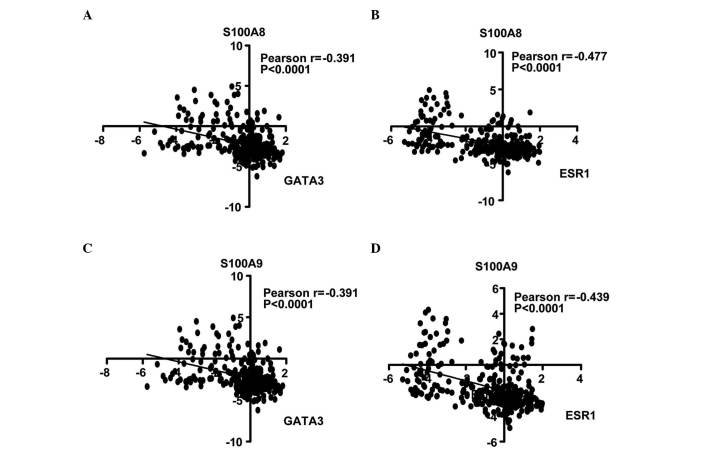

S100A8/A9 expression negatively correlates with ESR1 and GATA3 expression in BC

Calculation of the Pearson's correlation coefficient is a method of measuring the correlation (linear dependence) between two variables (X and Y), whereby a value between +1 and −1 is assigned (18). In the present study, the correlation of S100A8 and S100A9 with ESR1 and GATA3 genes was analyzed. In the NKI cohort, it was identified that S100A8 expression was inversely correlated with GATA3 (r=−0.391; Fig. 3A) and ESR1 expression (r=−0.477; Fig. 3B). Similarly, S100A9 was negatively correlated with GATA3 (r=−0.391; Fig. 3C) and ESR1 (r=−0.439; Fig. 3D). Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the correlations were significant (P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Correlation between the expression levels of (A) S100A8 and GATA3, (B) S100A8 and ESR1, (C) S100A9 and GATA3 and (D) S100A9 and ESR1 genes in GeneChip® data of breast cancer. GATA3, GATA binding protein 3; ESR1, estrogen receptor 1.

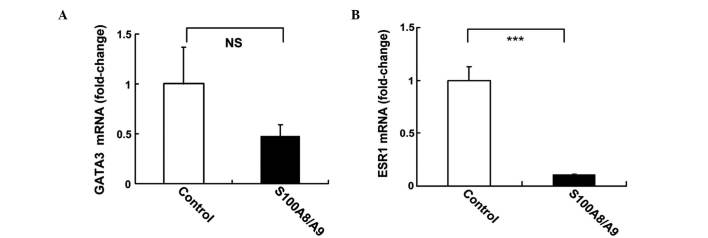

Treatment with S100A8/A9 regulates ESR1 in MCF-7 cells

The regulation of ESR1 and GATA3 gene expression by recombinant S100A8/A9 protein in MCF-7 cells was investigated using qPCR. MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml S100A8/A9 for 24 h. S100A8/A9 induced 50% inhibition of GATA3, although this was not statistically significant (P=0.078; Fig. 4A). S100A8/A9 induced a 10-fold reduction in the mRNA levels of ESR1 (P<0.001; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of recombinant S100A8/A9 protein on GATA3 and ESR1 gene expression in MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with 10 ng/ml S100A8/A9 for 24 h, while control cells received no treatment. (A) GATA3 and (B) ESR1 mRNA levels were measured using quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error. n=4/group. ***P<0.001 vs. control. GATA3, GATA binding protein 3; ESR1, estrogen receptor 1; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant.

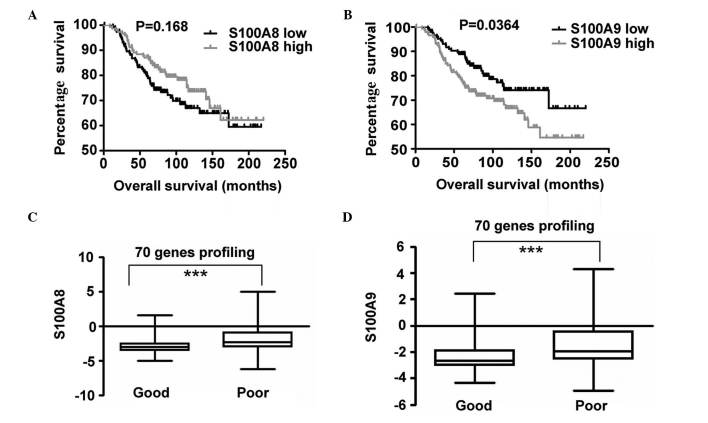

Increased expression of S100A9 correlates with BC prognosis

In order to investigate the expression of S100A8 and S100A9 and its association with OS, S100A8 and S100A9 expression profiling and clinical data provided by the NKI cohort was analyzed. Patients were divided into two groups based on the expression levels of S100A8 in the top 50th percentile and in the bottom 50th percentile. Survival curves of OS in the two groups were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared via the log-rank test. An identical measurement was performed on the basis of S100A9 gene expression. A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups, and increased S100A9 expression was identified to be associated with poor OS. However, no statistically significant difference was observed for S100A8 expression (Fig. 5). P-values were calculated using the log-rank test.

Figure 5.

Analysis of OS of patients with breast cancer based on the expression levels of S100A8 and S100A9, using the Netherlands Cancer Institute dataset. Patients were divided into two groups based on their messenger RNA levels of S100A8/A9. High expression levels of S100A8/A9 in the top 50th percentile represented one group, while low expression levels of S100A8/A9 in the bottom 50th percentile represented the other group. Kaplan-Meier OS curves based on the expression levels of (A) S100A8 and (B) S100A9. Expression levels of (C) S100A8 and (D) S100A9 in poor and good prognosis groups, based on a 70-gene signature profile. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error. OS, overall survival.

Discussion

In the present study, microarray data obtained from a published database was analyzed. Increased levels of S100A8 and S100A9 transcripts were observed to be present in Her2+/basal-like BC subgroups, whereas they were lower in luminal A/B subtypes. This observation indicated that the expression levels of S100A8/A9 may be associated with the expression levels of hormone receptors. Subsequently, it was identified that S100A8/A9 exhibited a significant inverse correlation with ESR1 and GATA3 expression.

ERs consist of two isoforms, ERα and ERβ, which have been identified to be expressed in multiple tissues, including the mammary gland (19). ERα is the primary type of ER in breast tissues, and is encoded by the ESR1 gene (20). High expression levels of ERα correlate with increased mRNA levels of ESR1 (19). A well-established role of ERα is the maintenance of a differentiated epithelial phenotype in the mammary gland (21).

GATA3 is the most extensively studied GATA transcription factor (22). Normal differentiation of duct epithelia may be terminated with a tissue-specific knockout of the GATA3 gene in mice (23), which indicates that GATA3 has a significant role in ductal epithelial cell differentiation during the development of the mammary gland. GATA3 expression has been reported to possess a positive correlation with ERα expression (24), and cooperates with ERα in the driving of luminal ductal epithelial cell differentiation during mammary gland maturation (25). It is considered that GATA3 is able to mediate ERα expression by binding to the promoter region of the ERα gene (26). Furthermore, increased expression of GATA3 appears to inhibit BC metastasis (27). It remains to be elucidated whether S100A8 and S100A9 have a role in development of the normal mammary gland. A previous study reported that a S100A9−/- knockout mouse model demonstrated no obvious cancer phenotype and was fertile; however, this study primarily focused on myeloid cell function (28). Whether S100A8/A9 has a role in ductal epithelial cell differentiation may be elucidated if breast tissue-specific knockout mice are generated.

The inverse correlation of ESR1 and GATA3 with S100A8 and S100A9 expression observed in the present study indicated that a negative regulation loop may exist between these genes. To address this issue, recombinant S100A8/A9 protein was used to treat MCF-7 cells, and strong inhibition of ESR1 gene expression was observed. By contrast, the mRNA levels of GATA3 demonstrated no significant change. It remains to be elucidated whether a positive feedback loop exists between ERα and GATA3, as a previous study revealed that GATA3 gene expression exhibited no response following administration of estradiol, which activates ER (29).

S100A8 and S100A9 are primarily released by myeloid cells. In the present study, S100A8 and S100A9 gene expression was not only present in BC cells, but S100A8 and S100A9 were additionally secreted by BC cells (30). Cells in the tumor microenvironment, including endothelial, stromal and infiltrating immune cells, exhibit crosstalk and affect the proliferation and survival of cancer cells (31). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a population of myeloid cells that are trafficked to the primary or metastatic sites of a tumor (32). MDSCs display immunosuppressive activities by reducing the proliferation and function of effector T cells (32). Blocking S100A8/A9 and its receptor RAGE on the surface of MDSCs restores T cell proliferation (7). A previous study demonstrated that overexpression of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1/2 in BC cells attracted MDSCs to accumulate in the tumor microenvironment (33). MDSCs release S100A8/A9, which enhances cancer cell survival and induces additional MDSC accumulation in tumor sites (33). The tumor-stroma paracrine axis provides a survival benefit for cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment (33). In the present study, it was difficult to clarify the primary source of elevated S100A8/A9 in ER− BC. S100A8/A9 may exert autocrine and/or paracrine roles, mediating downregulation of the expression of ESR1. The increased concentration of S100A8/A9 in the tumor microenvironment may contribute to resistance to endocrine therapy in ER+ BC, as a consequence of suppressing ERα expression.

Using a Kaplan-Meier survival curve, increased mRNA levels of S100A9 were observed to be associated with decreased OS and poor prognosis by analyzing the NKI data. It has been proposed that a 70-gene prognostic signature, the intrinsic subtypes and the recurrence score may be strongly concordant in the evaluation of BC outcome (34). In the present study, increased S100A8 and S100A9 expression was observed to be associated with poor prognosis and the 70-gene prognostic signature. The results of the present study suggested that the detection of the transcript levels of S100A9 may serve as an indicator for prediction of prognosis of BC.

In conclusion, the present study revealed increased mRNA expression levels of S100A8 and S100A9 in Her2+/basal-like BC. S100A8 and S100A9 genes are expressed in BC cells, and their expression is inversely correlated with ESR1 and GATA3 expression. Furthermore, treatment of S100A8/A9 in vitro repressed ESR1 expression in MCF-7 BC cells. Increased mRNA levels of S100A9 were associated with decreased OS in BC. Therefore, the results of the present study suggested that enhanced S100A8/A9 expression in the BC microenvironment may reduce the sensitivity of BC cells to endocrine therapy, possibly due to a loss of ER, and S100A8/A9 may serve as a biomarker for prediction of prognosis of BC.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the Chinese National Science Fund for Young Scholars (Beijing, China; grant no. 81101707), the Zhejiang Traditional Chinese Medicine Foundation Project (Hangzhou, China; grant no. 2014ZB119), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Hangzhou, China; grant no. LY16H070007) and the Science and Technology Bureau of Jiaxing (Jiaxing, China; grant no. 2012AY1071–2).

References

- 1.Hessian PA, Edgeworth J, Hogg N. MRP-8 and MRP-14, two abundant Ca(2+)-binding proteins of neutrophils and monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:4666–4675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heizmann CW, Fritz G, Schäfer BW. S100 proteins: Structure, functions and pathology. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1356–d1368. doi: 10.2741/heizmann. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srikrishna G. S100A8 and S100A9: New insights into their roles in malignancy. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:31–40. doi: 10.1159/000330095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan JK, Roth J, Oppenheim JJ, Tracey KJ, Vogl T, Feldmann M, Horwood N, Nanchahal J. Alarmins: Awaiting a clinical response. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2711–2719. doi: 10.1172/JCI62423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogl T, Eisenblätter M, Völler T, Zenker S, Hermann S, van Lent P, Faust A, Geyer C, Petersen B, Roebrock K, et al. Alarmin S100A8/S100A9 as a biomarker for molecular imaging of local inflammatory activity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Chang EW, Wong SC, Ong SM, Chong DQ, Ling KL. Increased myeloid-derived suppressor cells in gastric cancer correlate with cancer stage and plasma S100A8/A9 proinflammatory proteins. J Immunol. 2013;190:794–804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis-Filho JS, Pusztai L. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Classification, prognostication, and prediction. Lancet. 2011;378:1812–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holst F, Stahl PR, Ruiz C, Hellwinkel O, Jehan Z, Wendland M, Lebeau A, Terracciano L, Al-Kuraya K, Jänicke F, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene amplification is frequent in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:655–660. doi: 10.1038/ng2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prat A, Parker JS, Karginova O, Fan C, Livasy C, Herschkowitz JI, He X, Perou CM. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnenblick A, Fumagalli D, Sotiriou C, Piccart M. Is the differentiation into molecular subtypes of breast cancer important for staging, local and systemic therapy, and follow up? Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajria D, Chandarlapaty S. HER2-amplified breast cancer: Mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance and novel targeted therapies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:263–275. doi: 10.1586/era.10.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dey N, Smith BR, Leyland-Jones B. Targeting basal-like breast cancers. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:1510–1524. doi: 10.2174/138945012803530116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon A, Yong HY, Song JI, Cukovic D, Salagrama S, Kaplan D, Putt D, Kim H, Dombkowski A, Kim HR. Global gene expression profiling unveils S100A8/A9 as candidate markers in H-ras-mediated human breast epithelial cell invasion. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1544–1553. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin C, Li H, Zhang B, Liu Y, Lu G, Lu S, Sun L, Qi Y, Li X, Chen W. RAGE-binding S100A8/A9 promotes the migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells through actin polymerization and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:297–309. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell MJ, Machin D, editors. Medical Statistics: A Commonsense Approach. 3rd. London, UK: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerdivel G, Flouriot G, Pakdel F. Modulation of estrogen receptor alpha activity and expression during breast cancer progression. Vitam Horm. 2013;93:135–160. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416673-8.00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyoshi Y, Murase K, Saito M, Imamura M, Oh K. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor-α upregulation in breast cancers. Med Mol Morphol. 2010;43:193–196. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller SO, Clark JA, Myers PH, Korach KS. Mammary gland development in adult mice requires epithelial and stromal estrogen receptor α. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2357–2365. doi: 10.1210/en.143.6.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang SH, Chen Y, Weigel RJ. GATA-3 as a marker of hormone response in breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2009;157:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. GATA3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell. 2006;127:1041–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JQ, Litton J, Xiao L, Zhang HZ, Warneke CL, Wu Y, Shen X, Wu S, Sahin A, Katz R, et al. Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis and prognostic significance of TRPS-1, a new GATA transcription factor family member, in breast cancer. Horm Cancer. 2010;1:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s12672-010-0008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouros-Mehr H, Kim JW, Bechis SK, Werb Z. GATA3 and the regulation of the mammary luminal cell fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS, Brown M. Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA3 to estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6477–6483. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan W, Cao QJ, Arenas RB, Bentley B, Shao R. GATA3 inhibits breast cancer metastasis through the reversal of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14042–14051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobbs JA, May R, Tanousis K, McNeill E, Mathies M, Gebhardt C, Henderson R, Robinson MJ, Hogg N. Myeloid cell function in MRP-14 (S100A9) null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2564–2576. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2564-2576.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoch RV, Thompson DA, Baker RJ, Weigel RJ. GATA3 is expressed in association with estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:122–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990420)84:2<122::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebhardt C, Németh J, Angel P, Hess J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–379. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindau D, Gielen P, Kroesen M, Wesseling P, Adema GJ. The immunosuppressive tumour network: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells. Immunology. 2013;138:105–115. doi: 10.1111/imm.12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acharyya S, Oskarsson T, Vanharanta S, Malladi S, Kim J, Morris PG, Manova-Todorova K, Leversha M, Hogg N, Seshan VE, et al. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell. 2012;150:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan C, Oh DS, Wessels L, Weigelt B, Nuyten DS, Nobel AB, van't Veer LJ, Perou CM. Concordance among gene-expression- based predictors for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:560–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]