Abstract

In Drosophila, rhomboid proteases are active cardinal regulators of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway. iRhom1 and iRhom2, which are inactive homologs of rhomboid intramembrane serine proteases, are lacking essential catalytic residues. These are necessary for maturation and trafficking of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) converting enzyme (TACE) from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to plasma membrane through Golgi, and associated with the fates of various ligands for EGFR. Recent studies have clarified that the activation or downregulation of EGFR signaling pathways by alteration of iRhoms are connected to several human diseases including tylosis with esophageal cancer (TOC) which is the autosomal dominant syndrom, breast cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, this review focuses on our understanding of iRhoms and the involved mechanisms in the cellular processes.

Keywords: iRhom1, iRhom2, TNF-α, TACE, EGFR

INTRODUCTION

Rhomboid protease was initially discovered in Drosophila (Sturtevant et al., 1993; Freeman, 1994). Drosophila rhomboid protease cuts epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligand Spitz and a homologue for mammalian tumor growth factor (TGF)-α, triggering the secretion of the factors (Rutledge et al., 1992; Schweitzer et al., 1995). Homologs of the fly rhomboid proteases have been identified in most prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (Lemberg and Freeman, 2007). Rhomboid proteases comprise a superfamily of proteins consisting of intra-membrane serine proteases and their inactive homologs (Freeman, 2014). The common ancestor of all members of the family is probably an active intra-membrane protease, although the majority of existing members are not active proteases (Freeman, 2014).

The rhomboid protease family members have been shown to have a common structure, six or seven transmembrane domains (Ha et al., 2013) as seen in Table 1. Rhomboid proteases have conserved transmembrane segments of their polytopic rhomboid core domain, in which there are a catalytic motif in forth transmembrane domain, and an Engelman helix dimerization motif in sixth transmembrane domain (Urban et al., 2001; Urban et al., 2002; Lemberg et al., 2005; Urban and Wolfe, 2005). A tryptophan-arginine motif in loop 1 present between first and second transmembrane domains is also an invariant structure observed in rhomboid proteases.

Table 1.

Mammalian rhomboid family proteins

| Rhomboids | Number of TM domains | Catalase activity | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARL | 7 | Yes | Mitochondrial inner membrane |

| RHBDL1 | 7 | Yes (predicted) | Golgi |

| RHBDL2 | 7 | Yes | Plasma membrane |

| RHBDL3 | 7 | Yes (predicted) | Endosomes |

| RHBDL4 (RHBDD1) | 6 | Yes | ER |

| iRhom1 | 7 | No | ER-Golgi |

| iRhom2 | 7 | No | ER-Golgi |

| Derlin1 | 6 | No | ER |

| Derlin2 | 6 | No | ER |

| Derlin3 | 6 | No | ER |

| UBAC2 | 6 | No | ER |

| TMEM115 | 6 | No | ? |

| RHBDD2 | 6 | No | Golgi |

| RHBDD3 | 6 | No | ? |

Reference: Bergbold and Lemberg et al., 2013.

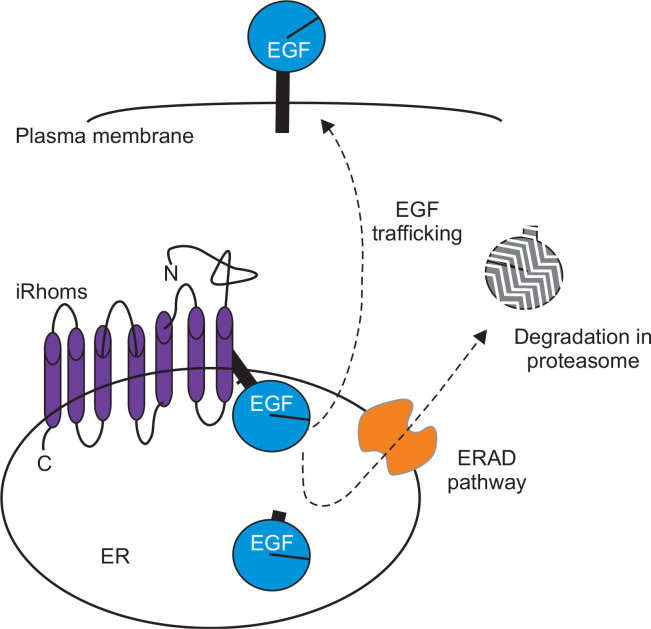

Although the first mammalian rhomboid protease was cloned and named RHBDL1 for rhomboid-like protein1 as early as before Drosophila Rhomboid-1 was recognized as intra-membrane protease (Pascall and Brown, 1998), the function is remained elusive yet. RHBDL2, however, was shown to share the catalytic activity of Drosophila Rhomboid-1. The localization of the known five mammalian rhomboid proteases is diversely scattered; golgi for RHBDL1, plasma membrane for RHBDL2, endosomes for RHBDL3, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for RHBDL4 and mitochondrial inner membrane for PARL (Bergbold and Lemberg, 2013), suggesting their distinct and diverse functions (Table 1). Actually only RHBDL2 can cleave and activate the mammalian proEGF (Adrain et al., 2011). And EGFR signaling is negatively modulated by RHBDL2-mediated lysosomal degradation of EGFR (Haglund and Dikic, 2012) or EGFR cleavage (Liao and Carpenter, 2012). On the other hand, RHBDL4 localizing to the ER can induce degradation of various substrates (Bergbold and Lemberg, 2013), as a part of ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery as shown in Fig. 1 (Fleig et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

Rhomboid protein iRhoms regulate the RGFR ligands in the ER. iRhoms binds to various EGFR ligands in the ER and facilitate their forward trafficking or ERAD pathway. The mechanism with which the fate determination of the EGFR ligands is not clear yet.

There are, however, other subgroups of rhomboid family members, calling iRhoms, with high sequence similarities. These rhomboid family members, iRhom1 and iRhom2, have no the key catalytic motif observed in rhomboid proteases, meaning inactive rhomboid (Lemberg and Freeman, 2007; Ha et al., 2013). iRhom1 and iRhom2 have lost their protease activity during their evolution but retained the key non-protease functions, which have been implicated in the regulation of EGF signaling pathway (Adrain et al., 2011) and TNF-α signaling pathway (Adrain et al., 2012).

As more distant rhomboid family members, many other genes without the key catalytic motif, such as derins, UBAC2, RHBDDs and TMEM115, have also been annotated as rhomboid-like proteins by bioinformatics search based on their sequence similarities (Koonin et al., 2003; Lemberg and Freeman, 2007; Finn et al., 2010). The structural relations for these proteins remain to be investigated because of their limited overall sequence conservation (Bergbold and Lemberg, 2013). Currently, there are 14 rhomboid family members, five rhomboid proteases and nine catalytically inactive homologues (Bergbold and Lemberg, 2013). Among these rhomboids, iRhoms comprise a unique family; not only with the key catalytic motif and the highly conserved sequences between species, but also with the unique iRhom homology domain and cytosolic N-terminal cytosolic domain, suggesting an important biological role for these proteins, despite their lack of protease activity (Koonin et al., 2003; Lemberg and Freeman, 2007; Freeman, 2014). This review focuses on our current understanding of iRhoms and their roles in cellular processes and diseases.

IRHOMS IN DROSOPHILA AND MAMMALS

In Drosophila, active rhomboids are cardinal regulators of EGFR signaling pathway, and their activity is conserved in mammals (Lui et al., 2003; Zettl et al., 2011). The principal ligand of Drosophila EGFR is Spitz, which is homologous to mammalian TGF-α. Spitz must be proteolytically released as a soluble extracellular fragment to be functional, and Rhomboid-1 is directly involved in the proteolytic cleavage of Spitz (Zou et al., 2009). Until now, genetic approaches have been used to investigate iRhom function in both Drosophila and mammals. Losses of function in mutated flies and mice have revealed the role of iRhoms in both ER-associated degradation and trafficking of TACE which is known to be responsible for the releases of active TNF and EGF family ligands (Siggs et al., 2014). EGF ligands in Drosophila are activated by its cleavage by Rhomboids. This is distinct from the metalloprotease-induced activation of mammalian EGF-like ligands (Siggs et al., 2014).

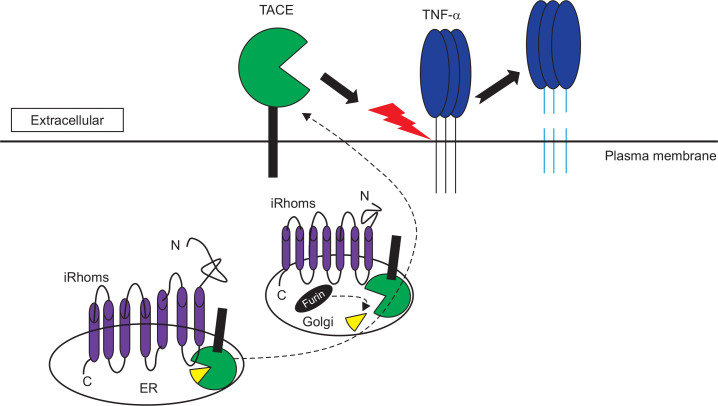

In mammals, iRhoms are known to regulate trafficking of TACE which is the protease that cleaves membrane-bound substrates including inflammatory cytokine TNF- as indicated in Fig. 2. Both in Drosophila and mammals, losses of function mutations in Drosophila and mice have revealed the role of iRhoms in both ER associated degradation, and the control of trafficking of the metalloprotease TACE, the enzyme that releases active TNF-α and ligands of the EGF family (Zettl et al., 2011; Adrain et al., 2012; McIlwain et al., 2012). Especially, it became clear that iRhoms in human are associated with inheritable diseases and cancers (Etheridge et al., 2013). Understanding on the underlying mechanisms would be an important task for using the related pathways as therapeutic targets.

Fig. 2.

Rhomboid protein iRhoms regulate the trafficking and maturation of TNF-a converting enzyme (TACE). iRhoms bind to TACE, which promotes its exit from ER to Golgi. Within the Golgi, TACE is processed by furin into its mature form. At the plasma membrane, TACE cleaves the membrane-bound form of TNF-α to generate soluble TNF-α, which binds to TNFR.

ESSENTIAL ROLE OF IRHOMS ON TACE REGULATION

TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) (also known as ADAM17) is a membrane-anchored metalloproteinase that controls two major pathways, the EGF receptor pathway and proinflammatory TNF-α pathway, with important roles in development and disease (Black et al., 1997; Peschon et al., 1998; Sahin et al., 2004). TACE is essential for release of EGFR ligands (Sahin et al., 2004; Sahin and Blobel, 2007) and TNF-α (Black et al., 1997; Issuree et al., 2013), which is the primary trigger of inflammation (Adrain et al., 2012). Like many extracellular signaling proteins, TNF-α is synthesized as a transmembrane protein, and the active signal of its ectodomain is shed from cells after cleavage by a metalloprotease, TACE (Black et al., 1997; Siggs et al., 2012). TNF-α is considered as a ‘fire alarm’ of the body, as it helps body fight against infections. But TNF-α can also cause diseases such as inflammatory arthritis (Haxaire and Blobel, 2014). TACE and its regulator, iRhom2, can be rapidly activated by small amounts of cytokines, growth factors, and pro-inflammatory mediators present in the blood (Hall and Blobel, 2012), substantiating rapid alarm through TNF-α. iRhoms are co-expressed with TACE and are essential for specific regulation of TACE activity as shown in Fig. 2 (Christova et al., 2013).

iRhom1 and iRhom2 are both essential for regulation of TACE (Zou et al., 2009). iRhom2 is highly expressed in macrophages but not in skin or other tissues (Christova et al., 2013) and is a key regulator in myeloid TACE (Lichtenthaler, 2013). Loss of iRhom2 blocks maturation of TACE in macrophages, resulting in defective shedding of TNF-α (Li et al., 2015). iRhom2 binds to TACE and promotes its transfer from the ER. Therefore, without iRhom2, TACE is unable to exit the ER and be trafficked to the Golgi apparatus where its inhibitory prodomain is removed by furin (Christova et al., 2013). Therefore, inactivation of iRhom2 in mice prevented maturation of TACE in hematopoietic cells but not other cells and tissues (Issuree et al., 2013), and targeting of iRhom2 effectively inactivated TACE in immune cells without affecting its function in other tissues (Wasserman et al., 2000; Lemberg, 2013). Its protective role in relation to TNF-α has been demonstrated in mouse models with shock induction by lipopoloysaccharide (Adrain et al., 2012) or with Listeria monocytogenes infection (McIlwain et al., 2012). Inactivation of iRhom2 in human macrophages also prevents maturation of TACE and release of TNF-α from cells, suggesting that the iRhom2/TACE/TNF-α pathway has been conserved in both mice and humans (Puente et al., 2003; Issuree et al., 2013). Therefore, iRhoms are considered as attractive novel targets for treatment of TACE/TNF-α-dependent pathologies (Issuree et al., 2013).

IRHOM-MEDIATED REGULATION OF EGFR SIGNALING

EGFRs are a family of receptor tyrosine kinases essential for the control of many cellular processes, including proliferation, survival, and differentiation (Lui et al., 2003). The EGFR ligand family includes EGF, TGF-α, amphiregulin (AR), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), betacellulin (BTC), epiregulin, and epigen (Bassik et al., 2013; Hosur et al., 2014). EGFR plays a major role in cancers as an activated oncogene (Lui et al., 2003). Activation of EGFR is frequently detected in a wide variety of carcinomas, including breast, lung, head and neck, and cervical cancers, and has been correlated with their poor prognosis (Zou et al., 2009). Several lines of evidence have implicated iRhoms in the regulation of EGFR signaling pathway. In Drosophila, active rhomboid proteins are cardinal regulators of EGFR signaling pathway which is activated throughout growth and development of wings (Lui et al., 2003). Clear involvement of rhomboid protein in EGFR activity was demonstrated using the sensitive developing wing primordium of Drosophila to reveal ectopic EGFR activity (Sturtevant et al., 1993; Nakagawa et al., 2005). Co-expression of iRhom1 with HB-EGF in Drosophila resulted in the severe wing phenotypes (Nakagawa et al., 2005). Drosophila iRhom deficiency induced sleep-like phenotype (Zettl et al., 2011), similar to the phenotype observed in increased activation of the EGFR pathway (Foltenyi et al., 2007). These results indicate Drosophila iRhoms are involved with inhibitory regulation of EGFR signaling pathway (Zettl et al., 2011; Freeman, 2014).

TACE can release not only membrane bound TNF-α but also various ligands of the EGFR. Therefore TACE can control a wide range of physiologically and medically important EGFR signaling (Blobel, 2005). An identification of iRhom1 and iRhom2 as key regulators of TACE-dependent EGFR signaling in mice highlighted an important role of iRhoms in the EGFR signaling pathway (Freeman, 2014; Siggs et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Coexpression of human iRhom1 or mouse iRhom2 with EGF family ligands in COS7 cells downregulated all the EGFR ligands (Zettl et al., 2011). On the other hand, in the response of rapid stimulation for release of some TACE substrates in iRhom2 mutant embryonic fibroblasts, shedding of HB-EGF, amphiregulin and epiregulin was downregulated, whereas the shedding of TGF-α was not changed. In the condition, there was no change in the mature TACE levels, suggesting that iRhom2 itself may be involved in determining substrate selectivity of TACE-dependent shedding (Maretzky et al., 2013; Freeman, 2014).

siRNA-mediated RHBDF1 gene silencing in cancer cell lines reduced the levels of cell migration and proliferation and induced apoptosis or autophagy in cancer cells (Zou et al., 2009). Moreover, iRhom1 is necessary for the survival of epithelial cancer cells in humans and may be linked to G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-mediated EGFR transactivation (Zettl et al., 2011). Collectively, these results indicate that iRhoms are not only promote forward trafficking of EGFR ligands from ER to Golgi, but also block ER export of the EGFR ligands by ERAD via the proteasome (Zettl et al., 2011; Bergbold and Lemberg, 2013) and that iRhoms may be attractive targets for treatment of TACE/EFGR-dependent pathologies (Li et al., 2015).

Different to an initial hypothesis that the iRhoms directly blocks active rhomboid proteases (Koonin et al., 2003), it reduces the level of growth factor substrates by triggering their degradation (Zettl et al., 2011). iRhom in Drosophila genetically interacts with the E3 ubiquitin ligase Hrd1 and the ERAD substrate receptor EDEM (Zettl et al., 2011). In addition, human iRhom1 and mouse iRhom2 have been demonstrated to mediate the down-regulation of EGF signaling pathway by binding to EGF ligands in the ER and targeting them for ERAD, which is induced as a result of ER quality control mechanisms (Etheridge et al., 2013). Therefore, both Drosophila and mammals share iRhom-mediated ERAD of EGF family ligands in regulation of EGF signaling pathway (Urban and Dickey, 2011), although there is no solid evidence for physiological role of iRhoms in regulating ERAD in mammals (Siggs et al., 2014). The exact mechanism whether EGFR ligands are exported or degraded is not clear yet.

POTENTIAL ROLE OF IRHOMS IN HUMAN DISEASE

Although iRhoms have no protease activity, they regulate the secretion of several ligands of EGFR and proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. Therefore, iRhoms can activate the EGFR signaling pathway and inflammation process, which regulate cell survival, proliferation, migration and inflammation, resulting in modifications of disease condition. Two recent studies reported a strong association between Alzheimer’s disease and changes in iRhom2 methylation in the brain (De Jager et al., 2014; Lunnon et al., 2014). They showed that the methylation level in the RHBDF2 gene was changed in Alzheimer’s disease and the RHBDF2 expression was increased in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. In their connectivity analysis, RHBDF2 was connected to PTK2B that is a key element gene of signaling cascade involved in modulating the activation of microglia and infiltrating macrophages. Therefore, changes in methylation in iRhom2 gene and its increased expression may be associated with the role of microglia and infiltrating macrophages in Alzheimer’s disease (De Jager et al., 2014).

Missense mutations in RHBDF2, iRhom2 encoding gene, were shown to cause tylosis esophageal cancer (TOC), the autosomal dominant condition, in four families from the UK, US, Germany and Finland (Blaydon et al., 2012; Saarinen et al., 2012). TOC is an inherited condition characterized by palmoplantar keratoderma and esophageal cancer (Abbruzzese et al., 2012; Rugg et al., 2002). Palmoplantar keratoderma usually begins around age 10, and esophageal cancer may form after age 20. The mutations occurred in the N-terminal domain of iRhom2, which has a highly conserved region in different species as well as between iRhom1 and iRhom2 (Blaydon et al., 2012). These reports indicate that the N-terminal domain may have some important functions, but little is known yet. On the other hand, unusual distribution of iRhom2 is reported in normal skin. The iRhom2 expression is detected primarily at the plasma membrane in the normal epidermis and is much more diffuse in cells from TOC patients (Blaydon et al., 2012), instead of ER and Golgi localization in macrophages. Alteration of iRhom2 localization was also observed in tylotic and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (Blaydon et al., 2012). Moreover, there is recent evidence that these TOC-associated mutations in iRhom2 induce TACE activation in epidermal keratinocytes, resulting in increased shedding of TACE substrates including EGF-family growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Brooke et al., 2014). These results may explain the high proliferative activity of TOC cells and the predisposed esophageal cancer development in TOC patients. The mutations of iRhom2 in TOC patients may also regulate the EFGR signal pathways by altering proEGF targeting of iRhom2 for ERAD (Zettl et al., 2011), instead of activation by EFGR cleavage by RHBDL2 (Adrain et al., 2011). These mutations in iRhom2 are also associated with ovarian cancer (Wojnarowicz et al., 2012). iRhom2 expressions were much lower in a subset of benign and malignant ovarian tumors compared with primary cultured cells from normal ovarian epithelium.

Altered iRhom1 may cause squamous epithelial cancer and breast cancer (Yan et al., 2008; Zou et al., 2009). iRhom1 expression is elevated in breast cancer samples and knockdown of iRhom1 by siRNA has led diminished EGFR transactivation in tissue culture cells (Zou et al., 2009).

CONCLUSION

iRhoms are unique members in Rhomboid family with unique domains as well as no catalytic active motif, suggesting an important biological role for these proteins, despite their lack of protease activity (Koonin et al., 2003; Lemberg and Freeman, 2007; Freeman, 2014). In facts, recent studies started to reveal their diverse roles in TACE maturation and in EGFR signaling pathways. It appears that iRhomes are associated with development of several human diseases including cancers. The fact that iRhomes interact with TACE provides novel therapeutic opportunities for selective and simultaneous inactivation of the major signaling pathways which are closely associated with the disease development (Lisi et al., 2014). Hyperactivity of EGFR is implicated in many tumors with several molecular mechanisms, including the autocrine activation of EGFR by unregulated release of ligands (Buckland, 2013). Recent research data provide genetic, cellular, and biochemical evidence that the principal function of iRhoms1/2 is regulated by TACE-dependent TNF-α or EGFR signaling pathway, suggesting that iRhoms1/2 could emerge as novel targets for treatment of TACE/TNF-α and TACE/EGFR- dependent pathologies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (2013M3A9D5072559) and Priority Research Centers Program (2015R1A6A1A04020885) of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation of the Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to publish the results.

REFERENCES

- Abbruzzese C, Mattarocci S, Pizzuti L, Mileo AM, Visca P, Antoniani B, Alessandrini G, Facciolo F, Amato R, D’Antona L, Rinaldi M, Felsani A, Perrotti N, Paggi MG. Determination of SGK1 mRNA in non-small cell lung cancer samples underlines high expression in squamous cell carcinomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:4. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrain C, Strisovsky K, Zettl M, Hu L, Lemberg MK, Freeman M. Mammalian EGF receptor activation by the rhomboid protease RHBDL2. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:421–427. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrain C, Zettl M, Christova Y, Taylor N, Freeman M. Tumor necrosis factor signaling requires iRhom2 to promote trafficking and activation of TACE. Science. 2012;335:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1214400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassik MC, Kampmann M, Lebbink RJ, Wang S, Hein MY, Poser I, Weibezahn J, Horlbeck MA, Chen S, Mann M, Hyman AA, Leproust EM, McManus MT, Weissman JS. A systematic mammalian genetic interaction map reveals pathways underlying ricin susceptibility. Cell. 2013;152:909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbold N, Lemberg MK. Emerging role of rhomboid family proteins in mammalian biology and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:2840–2848. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon DC, Etheridge SL, Risk JM, Hennies HC, Gay LJ, Carroll R, Plagnol V, McRonald FE, Stevens HP, Spurr NK, Bishop DT, Ellis A, Jankowski J, Field JK, Leigh IM, South AP, Kelsell DP. RHBDF2 mutations are associated with tylosis, a familial esophageal cancer syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel CP. ADAMs: key components in EGFR signalling and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:32–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke MA, Etheridge SL, Kaplan N, Simpson C, O’Toole EA, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Marches O, Getsios S, Kelsell DP. iRHOM2-dependent regulation of ADAM17 in cutaneous disease and epidermal barrier function. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4064–4076. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckland J. Experimental arthritis: Antihistamines as treatments for autoimmune disease? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:696. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christova Y, Adrain C, Bambrough P, Ibrahim A, Freeman M. Mammalian iRhoms have distinct physiological functions including an essential role in TACE regulation. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:884–890. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, Eaton ML, Keenan BT, Ernst J, McCabe C, Tang A, Raj T, Replogle J, Brodeur W, Gabriel S, Chai HS, Younkin C, Younkin SG, Zou F, Szyf M, Epstein CB, Schneider JA, Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Ertekin-Taner N, Chibnik LB, Kellis M, Mill J, Bennett DA. Alzheimer’s disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1156–1163. doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge SL, Brooke MA, Kelsell DP, Blaydon DC. Rhomboid proteins: a role in keratinocyte proliferation and cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig L, Bergbold N, Sahasrabudhe P, Geiger B, Kaltak L, Lemberg MK. Ubiquitin-dependent intramembrane rhomboid protease promotes ERAD of membrane proteins. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:558–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltenyi K, Greenspan RJ, Newport JW. Activation of EGFR and ERK by rhomboid signaling regulates the consolidation and maintenance of sleep in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/nn1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. The spitz gene is required for photoreceptor determination in the Drosophila eye where it interacts with the EGF receptor. Mech Dev. 1994;48:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. The rhomboid-like superfamily: molecular mechanisms and biological roles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-012944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y, Akiyama Y, Xue Y. Structure and mechanism of rhomboid protease. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15430–15436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.422378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K, Dikic I. The role of ubiquitylation in receptor endocytosis and endosomal sorting. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:265–275. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KC, Blobel CP. Interleukin-1 stimulates ADAM17 through a mechanism independent of its cytoplasmic domain or phosphorylation at threonine 735. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxaire C, Blobel CP. With blood in the joint - what happens next? Could activation of a pro-inflammatory signalling axis leading to iRhom2/TNFalpha-convertase-dependent release of TNFalpha contribute to haemophilic arthropathy? Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 4):11–14. doi: 10.1111/hae.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosur V, Johnson KR, Burzenski LM, Stearns TM, Maser RS, Shultz LD. Rhbdf2 mutations increase its protein stability and drive EGFR hyperactivation through enhanced secretion of amphiregulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2200–E2209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323908111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issuree PD, Maretzky T, McIlwain DR, Monette S, Qing X, Lang PA, Swendeman SL, Park-Min KH, Binder N, Kalliolias GD, Yarilina A, Horiuchi K, Ivashkiv LB, Mak TW, Salmon JE, Blobel CP. iRHOM2 is a critical pathogenic mediator of inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:928–932. doi: 10.1172/JCI66168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Rogozin IB, Davidovic L, Letellier MC, Pellegrini L. The rhomboids: a nearly ubiquitous family of intramembrane serine proteases that probably evolved by multiple ancient horizontal gene transfers. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg MK. Sampling the membrane: function of rhomboid-family proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg MK, Freeman M. Functional and evolutionary implications of enhanced genomic analysis of rhomboid intramembrane proteases. Genome Res. 2007;17:1634–1646. doi: 10.1101/gr.6425307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg MK, Menendez J, Misik A, Garcia M, Koth CM, Freeman M. Mechanism of intramembrane proteolysis investigated with purified rhomboid proteases. EMBO J. 2005;24:464–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Maretzky T, Weskamp G, Monette S, Qing X, Issuree PD, Crawford HC, McIlwain DR, Mak TW, Salmon JE, Blobel CP. iRhoms 1 and 2 are essential upstream regulators of ADAM17-dependent EGFR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6080–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505649112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HJ, Carpenter G. Regulated intramembrane cleavage of the EGF receptor. Traffic. 2012;13:1106–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler SF. iRHOM2 takes control of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:560–562. doi: 10.1172/JCI67548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisi S, D’Amore M, Sisto M. ADAM17 at the interface between inflammation and autoimmunity. Immunol Lett. 2014;162:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui VW, Thomas SM, Zhang Q, Wentzel AL, Siegfried JM, Li JY, Grandis JR. Mitogenic effects of gastrin-releasing peptide in head and neck squamous cancer cells are mediated by activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncogene. 2003;22:6183–6193. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunnon K, Smith R, Hannon E, De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Volta M, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Burrage J, Macdonald R, Condliffe D, Harries LW, Katsel P, Haroutunian V, Kaminsky Z, Joachim C, Powell J, Lovestone S, Bennett DA, Schalkwyk LC, Mill J. Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1164–1170. doi: 10.1038/nn.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretzky T, McIlwain DR, Issuree PD, Li X, Malapeira J, Amin S, Lang PA, Mak TW, Blobel CP. iRhom2 controls the substrate selectivity of stimulated ADAM17-dependent ectodomain shedding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11433–11438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302553110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain DR, Lang PA, Maretzky T, Hamada K, Ohishi K, Maney SK, Berger T, Murthy A, Duncan G, Xu HC, Lang KS, Haussinger D, Wakeham A, Itie-Youten A, Khokha R, Ohashi PS, Blobel CP, Mak TW. iRhom2 regulation of TACE controls TNF-mediated protection against Listeria and responses to LPS. Science. 2012;335:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1214448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Guichard A, Castro CP, Xiao Y, Rizen M, Zhang HZ, Hu D, Bang A, Helms J, Bier E, Derynck R. Characterization of a human rhomboid homolog, p100hRho/RHBDF1, which interacts with TGF-alpha family ligands. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1315–1331. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascall JC, Brown KD. Characterization of a mammalian cDNA encoding a protein with high sequence similarity to the Drosophila regulatory protein Rhomboid. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00622-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Johnson RS, Fitzner JN, Boyce RW, Nelson N, Kozlosky CJ, Wolfson MF, Rauch CT, Cerretti DP, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Black RA. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Overall CM, López-Otín C. Human and mouse proteases: a comparative genomic approach. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:544–558. doi: 10.1038/nrg1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg EL, Common JE, Wilgoss A, Stevens HP, Buchan J, Leigh IM, Kelsell DP. Diagnosis and confirmation of epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma by the identification of mutations in keratin 9 using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:952–957. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge BJ, Zhang K, Bier E, Jan YN, Perrimon N. The Drosophila spitz gene encodes a putative EGF-like growth factor involved in dorsal-ventral axis formation and neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1503–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen S, Vahteristo P, Lehtonen R, Aittomäki K, Launonen V, Kiviluoto T, Aaltonen LA. Analysis of a Finnish family confirms RHBDF2 mutations as the underlying factor in tylosis with esophageal cancer. Fam. Cancer. 2012;11:525–528. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9532-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Blobel CP. Ectodomain shedding of the EGF-receptor ligand epigen is mediated by ADAM17. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, Zhou HM, Higashiyama S, Peschon J, Hartmann D, Saftig P, Blobel CP. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Shaharabany M, Seger R, Shilo BZ. Secreted Spitz triggers the DER signaling pathway and is a limiting component in embryonic ventral ectoderm determination. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1518–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggs OM, Grieve A, Xu H, Bambrough P, Christova Y, Freeman M. Genetic interaction implicates iRhom2 in the regulation of EGF receptor signalling in mice. Biol. Open. 2014;3:1151–1157. doi: 10.1242/bio.201410116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggs OM, Xiao N, Wang Y, Shi H, Tomisato W, Li X, Xia Y, Beutler B. iRhom2 is required for the secretion of mouse TNFα. Blood. 2012;119:5769–5771. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-417949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant MA, Roark M, Bier E. The Drosophila rhomboid gene mediates the localized formation of wing veins and interacts genetically with components of the EGF-R signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1993;7:961–973. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Dickey SW. The rhomboid protease family: a decade of progress on function and mechanism. Genome Biol. 2011;12:231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Lee JR, Freeman M. Drosophila rhomboid-1 defines a family of putative intramembrane serine proteases. Cell. 2001;107:173–182. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Schlieper D, Freeman M. Conservation of intramembrane proteolytic activity and substrate specificity in prokaryotic and eukaryotic rhomboids. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1507–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Wolfe MS. Reconstitution of intramembrane proteolysis in vitro reveals that pure rhomboid is sufficient for catalysis and specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1883–1888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman JD, Urban S, Freeman M. A family of rhomboid-like genes: Drosophila rhomboid-1 and roughoid/rhomboid-3 cooperate to activate EGF receptor signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1651–1663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnarowicz PM, Provencher DM, Mes-Masson AM, Tonin PN. Chromosome 17q25 genes, RHBDF2 and CYGB, in ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1865–1880. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Zou H, Tian F, Grandis JR, Mixson AJ, Lu PY, Li LY. Human rhomboid family-1 gene silencing causes apoptosis or autophagy to epithelial cancer cells and inhibits xenograft tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1355–1364. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettl M, Adrain C, Strisovsky K, Lastun V, Freeman M. Rhomboid family pseudoproteases use the ER quality control machinery to regulate intercellular signaling. Cell. 2011;145:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Thomas SM, Yan ZW, Grandis JR, Vogt A, Li LY. Human rhomboid family-1 gene RHBDF1 participates in GPCR-mediated transactivation of EGFR growth signals in head and neck squamous cancer cells. FASEB J. 2009;23:425–432. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]