Abstract

Glioma is known to induce local and systemic immunosuppression, which inhibits antitumor T cell responses. The galectin-9-Tim-3-pathway negatively regulates T cell pathways in the tumor immunosuppressive environment. The present study assessed the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 in glioma patients, and evaluated the association between the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 with clinical characteristics. The present study identified that Tim-3 expression was significantly increased in peripheral blood T cells of glioma patients compared with those of healthy controls, and was additionally increased on tumor-infiltrating T cells. The expression of Tim-3 on tumor-infiltrating T cells was associated with the World Health Organization (WHO) grade of glioma, but negatively correlated with the Karnofsky Performance Status score of the glioma patients. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the expression of galectin-9 in tumor tissues was associated with Tim-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells and the WHO grade of glioma. These findings suggest that the galectin-9-Tim-3 pathway may be critical in the immunoevasion of glioma and may be a potent target for immunotherapy in glioma patients.

Keywords: glioma, T cells, Tim-3, galectin-9, immunoevasion, clinical manifestation

Introduction

Glioma is the most common type of primary malignant cerebral tumor and possesses a high cancer-associated mortality rate (1). Despite advances in surgical techniques, chemotherapy drugs and radiotherapy, the prognosis for glioma patients is poor (2). Malignant tumors may form immunosuppressive environments to evade immunological attacks (3). Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and its ligand programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) have been widely studied as a crucial pathway in the creation of the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment, which causes exhaustion or dysfunction of antitumor T lymphocytes. A blockade of this pathway by specific antibodies has resulted in impressive clinical responses in patients with solid tumors of various origins (4,5).

T cell immunoglobulin (Ig) and mucin-domain-containing molecule 3 (Tim-3) is an inhibitory receptor expressed on the surface of T cells and is critical for the inhibition of T cell responses against tumors (6). Galectin-9 has been identified as a ligand for Tim-3, and the binding of galectin-9 to Tim-3 results in the apoptosis of T cells and a negative regulation of T cell immunity (7). An in vivo study demonstrated that administration of Tim-3-Ig partly abrogated immune tolerance and reversed the suppressed function of immune cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B (8). Numerous studies support that a blockade of the galectin-9-Tim-3 pathway may have the potential to restore the function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human cancer. Gliomas have been revealed to induce local and systemic immunosuppression that limits the immune defense towards the tumor by the upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines and expansion of immunosuppressive effector cells, including regulatory T cells. Gliomas may also express immunosuppressive ligands at the cell surface, such as PD-L1 and B7-H3, an immune checkpoint molecule (9,10). However, the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 in gliomas has not been well studied. The present study assessed the expression of Tim-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and galectin-9 expression in tumor tissues of glioma patients. The significance of the expression of the galectin-9-Tim-3 pathway in gliomas was evaluated by analyzing the association between the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 and the clinical indices of glioma patients.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Peripheral blood and glioma tissues were collected from 53 patients during surgical resections performed at the Sanbo Brain Hospital (Beijing, China) between June 2012 and June 2014. All the patients had been previously diagnosed with glioma and had not undergone any cancer therapy prior to resection. Patients with other diseases, including other cancers, were excluded. For control tissues, 5 non-cancerous brain tissue samples were collected from patients with severe head injuries, who were undergoing surgery. All glioma tissue was pathologically graded according to the World Health Organization (WHO) glioma classification (11). Clinical information, including gender, age and the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scores, was obtained from the medical records of the patients.

The present study was authorized by the Ethical Board of the Sanbo Brain Hospital, and the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Biophysics (Beijing, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Cell isolation

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were isolated from glioma patients, as previously described (12,13). Briefly, the fresh glioma tissues were minced with sterile scissors and digested with 0.1 mg/ml hyaluronidase (catalog no., H3506; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (catalog no., 17104-019; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 0.01 mg/ml DNase I (catalog no., D5025; Sigma-Aldrich) in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; catalog no., P3563; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 60 min. The resulting tissue suspension was filtered through a BD Falcon 100-µm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and layered on 22% Percoll solution (catalog no., P1644; Sigma-Aldrich) in myelin buffer [produced according to a previously described protocol (12)], which removed the myelin and cell debris following continuous centrifugation for 20 min at 950 × g. The pellet of cells was additionally isolated by continuous density gradient centrifugation with 25 and 75% Percoll solution for 25 min at 800 × g. The cells between the 2 layers of Percoll solution were collected, and they consisted of microglia, tumor infiltrated macrophages and lymphocytes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from venous blood samples by continuous density Ficoll gradient (Tianjin Haoyang Biology Manufacture Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) centrifugation for 20 min at 800 × g. The white layer between the plasma and the Ficoll solution was collected and washed with sterile PBS.

Immunohistochemistry

Out of the 53 glioma tissues, only those that were large enough underwent immunohistochemical analysis. Therefore, a total of 40 glioma tissues and 5 non-cancerous brain tissues, which were obtained from severely brain-injured patients as controls during surgery, were used in the present study. The tissue sections were fixed in 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin and were prepared into 5 µm continuous sections. A streptavidin-biotin complex immunohistochemistry method was performed to determine the expression of galectin-9 using the DAB kit (catalog no., ZLI-9018; ZSBIO, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer's protocols, with the rabbit anti-human galectin-9 polyclonal antibody (dilution, 1:500; catalog no., ab183965; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for immunolabeling. Each tissue section was viewed at a ×400 magnification through 10 randomly selected fields of view, and the percentage of positive staining for galectin-9 and the staining intensity was analyzed by Image-Pro® Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). The expression levels of galectin-9 were scored based on the staining intensity and distribution using the immunoreactive score (IRS), as follows: IRS = staining intensity (SI) × percentage of positive cells (PP). The SI was determined as follows: Absent, 0; weak, 1; moderate, 2; and strong, 3. The PP was scored as follows: 0%, 0; 0–25%, 1; 25–50%, 2; 50–75%, 3; and 75–100%, 4 (14,15).

Flow cytometry

TILs and PBMCs were resuspended with fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (PBS with 3% fetal bovine serum; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and blocked with 10% human health serum (Beijing Red Cross Blood Center, Beijing, China) for 20 min at 4°C, and then stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using BD FACSCalibur™ (BD Biosciences). In total, ~10,000 cells were collected, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). The fluorescence-conjugated antibodies were as follows: Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated human anti-Tim-3 rat IgG2a monoclonal antibody (catalog no., FAB2365P; dilution, 50 µg/ml−1; R&D Systems China Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); PerCp-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-human cluster of differentiation (CD)3 mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no., 45-0037-42; dilution, 10 µg/ml−1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human CD8 mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no., 17-0086-42; dilution, 10 µg/ml−1; eBioscience); and PE-conjugated rat IgG2a isotype control antibody (catalog no. IC006P; dilution, 50 µg/ml−1; R&D Systems China Co., Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

All data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess galectin-9 and Tim-3 expression in different glioma tissues and the association between the expression and the WHO glioma grade. Spearman's correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation between the KPS score and the expression of galectin-9 and Tim-3 on T cells. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 53 glioma patients (30 men and 23 women) that possessed different grades of malignant glioma and were undergoing radical resection were enrolled in the present study. The characteristics of the patients are reported in Table I. The gliomas of the patients were classified according to the WHO classification of glioma, as follows: grade II, 7 patients; grade III, 15 patients; and grade IV, 31 patients. The KPS score was calculated according to the clinical records of the patients, as follows: ≥80, 22 patients; 60–80, 8 patients; and ≤60, 13 patients.

Table I.

Characteristics of glioma and control patients.

| Characteristic | Glioma patients, n (%) | Control patients, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 53 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 (56.6) | 7 (46.7) |

| Female | 23 (43.4) | 8 (53.3) |

| Age, years | ||

| 18–29 | 8 (15.1) | 4 (26.7) |

| 30–50 | 33 (62.3) | 8 (53.3) |

| ≥51 years | 12 (22.6) | 3 (20.0) |

| WHO grade | ||

| II–III | 22 (41.5) | N.A. |

| IV | 31 (58.5) | N.A. |

| KPS | ||

| ≥80 | 22 (41.5) | N.A. |

| 60–80 | 18 (34.0) | N.A. |

| <60 | 13 (24.5) | N.A. |

The differences between the groups were not significant. N.A., not applicable; WHO, World Health Organisation; KPS, Karnofsky performance status.

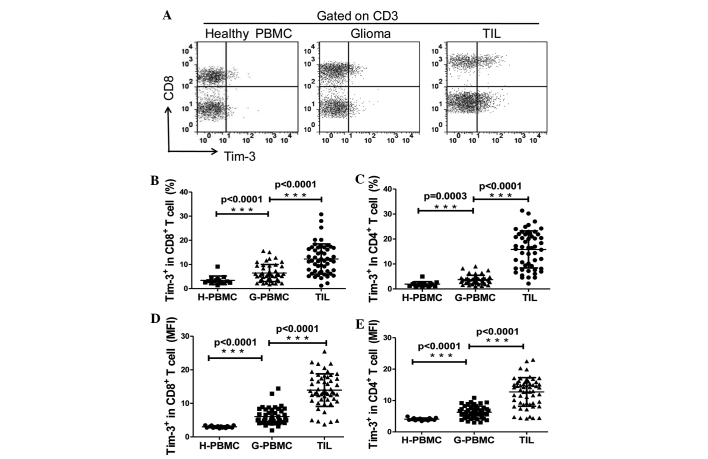

Tim-3 expression is upregulated on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and tumors of glioma patients

The expression levels of Tim-3 in T cells in tumor tissues and the peripheral blood of glioma patients, as well as in the peripheral blood of the control patients, was explored. TILs and PBMCs were analyzed directly by flow cytometry using the human anti-Tim-3, anti-human CD3 and the anti-human CD8 antibodies. CD4+ T cells were identified as CD3+/CD8− cells during flow cytometry analysis. As revealed in Fig. 1A, the expression of Tim-3 was slightly detected on T cells in PBMCs of the control patients, in which the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the frequencies of Tim-3+ cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were 1.92±0.26% and 3.43±0.46%, respectively. The frequency of Tim-3+ cells was ~2-fold higher on CD4+ (3.73±0.27%; P<0.05) and CD8+ T cells (6.46±0.52%; P<0.05) in PBMCs from the glioma patients compared with the control individuals. In addition, Tim-3 expression was increased ~4-fold on the CD4+ T cells (5.83±1.02%; P<0.0001) and ~2-fold on the CD8+ T cells (12.27±0.85%; P<0.0001) of TILs compared with the expression in the PBMCs obtained from the glioma patients (Fig. 1B and C). Similar observations were made when Tim-3 expression was analyzed as the mean fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1D and E). No differences were detected between Tim-3 expression on the CD4+/CD8+ T cells of PBMCs or TILs in male and female patients or different age groups (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Tim-3 expression is upregulated on the T cells of glioma patients; therefore, the glioma microenvironment may be important in regulating Tim-3 expression on T cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of Tim-3 on T cells in PBMC and TILs. (A) A representative flow cytometry analysis of lymphocytes of PBMCs from control and glioma patients, and TILs from glioma patients, stained with CD3, CD8 and Tim-3 antibodies. (B and C) Relative percentage of Tim-3-expressing cells in (B) CD8+ T cells (CD3+/CD8+; H-PBMC, 3.433±0.4631, n=15; G-PBMC, 6.461±0.5203, n=46; and TILs 12.27±0.8598, n=53). (C) CD4+ T cells (CD3+/CD8−; H-PBMC, 1.923±0.2562, n=15; G-PBMC 3.732±0.2574, n=46; and TILs 15.83±1.017, n=53). (D and E) MFI of Tim-3 expression on (D) CD8+ T cells (H-PBMC, 3.002±0.0788, n=15; G-PBMC 6.065±0.3556, n=46; and TIL 13.93±0.6663, n=53). (E) CD4+ T cells (H-PBMC, 4.041±0.1030, n=15; G-PBMC 6.263±0.2892, n=46; and TILs 12.73±0.6112, n=53). GraphPad Prism 5 software was used to calculate Mann-Whitney U test. Significance was indicated by P-values; ***P<0.001. Each symbol represents a single individual. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CD, cluster of differentiation; Tim-3, T cell immunoglobulin- and mucin-domain-containing molecule 3; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; H-PBMC, control patient PBMC; G-PBMC, glioma patient PBMC; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

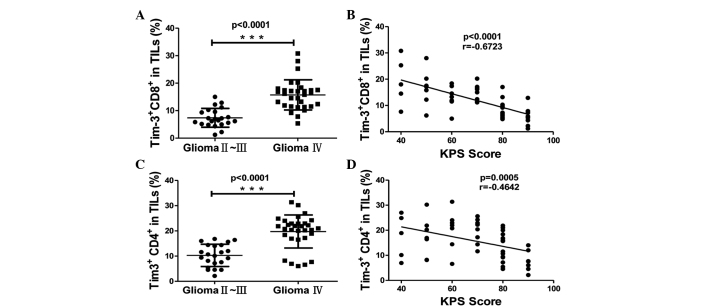

Tim-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells was associated with clinical pathological characteristics

Several clinicopathological features have been clinically used as prognostic factors for glioma, including the WHO grade of glioma and the KPS score. The KPS score is a standard method for measuring the ability of cancer patients to perform ordinary tasks, which is used to evaluate the severity of glioma (16). A lower KPS score indicates increased severity of the disease and a reduced survival time of patients. The WHO grade of glioma (17) and the KPS score have been demonstrated to be associated with the overall survival rate of patients, since patients with high-grade glioma and a KPS score of <80 possess a poorer overall survival rate and a higher risk of mortality compared with those with a low WHO grade and a KPS score of ≥80. To investigate the significance of Tim-3 expression on the T cells of glioma patients, the present study analyzed the association between the expression level of Tim-3 in T cells and the WHO grade of the glioma and KPS score of the glioma patients. Tim-3 expression on the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of TILs was increased in grade IV gliomas compared with grade II and III gliomas, suggesting that Tim-3 expression on T cells in tumors was significantly associated with the WHO grade of glioma (P<0.0001; Fig. 2A and B). The frequency of Tim-3+ cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of TILs was negatively correlated with the KPS score of glioma patients (P<0.001, r=−0.6723 and P=0.0005, r=−0.4642, respectively; Fig. 2C and D). This data indicates that the expression of Tim-3 on TILs was associated with glioma severity. The Tim-3 expression on the CD4+ T cells was slightly increased compared to the expression on the CD8+ T cells of TILs (mean ± SEM, 15.83±1.02% vs. 12.27±0.85%; Fig. 1B and C); however, the Tim-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells demonstrated an increased correlation with the KPS score compared with tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2B). This data demonstrates that the expression of Tim-3 on tumor-infiltrating T cells was associated with the prognosis of glioma patients.

Figure 2.

The association between Tim-3 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in TILs and the clinicalpathological characteristics of patients. (A and B) Association between Tim-3 expression and the World Health Organisation grade of glioma, as calculated by Mann-Whitney U test, on (A) CD8+ (glioma grade II–III, 7.391±0.727, n=22; and glioma grade IV, 15.72±0.9835, n=31) and (B) CD4+ T cells (glioma grade II–III, 10.29±0.9405, n=22; and glioma grade IV, 19.76±1.117, n=31). (C and D) Correlation between Tim-3 expression and the KPS score of patients, as calculated by Spearman's correlation analysis, on (C) CD8+ and (D) CD4+ T cells. Significance was indicated by P-values, ***P<0.001. Each symbol represents a single individual. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. CD, cluster of differentiation; Tim-3, T cell immunoglobulin- and mucin-domain-containing molecule 3; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status.

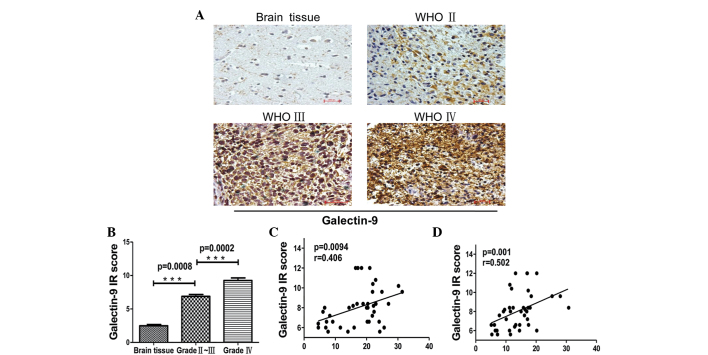

Galectin-9 expression in tumors was associated with the WHO grade of glioma and Tim-3 expression on the T cells of TILs. Galectin-9 is a ligand for Tim-3

The interaction of Tim-3 with galectin-9 induces the apoptosis of Tim-3+ T cells and inhibits T helper cell (Th)-1 responses. To assess the significance of Tim-3 signaling in gliomas, the present study examined the expression of galectin-9 in tumor cells using immunohistochemistry. Galectin-9 was expressed at an extremely low level in non-cancerous brain tissues from control patients, but there was an increased expression in glioma patient tissues. The expression level of galectin-9 in tumor tissues was scored as the IRS based on the intensity and distribution of galectin-9 staining. The IRS of galectin-9 was correlated with the WHO grade of glioma. The expression of galectin-9 in grade IV gliomas was significantly increased compared with grade II–III gliomas (Fig. 3A and B; P=0.008 vs. P=0.0002, respectively). In addition, galectin-9 expression in glioma tissue was associated with Tim-3 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of TILs (Fig. 3C and D; P=0.0094, r=0.406 and P=0.001, r=0.502, respectively). This data indicates that the galectin-9/Tim-3 pathway may be critical in the progression of glioma.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of glioma tissues for galectin-9 expression. (A) Paraffin-embedded tissue sections from injured brain tissue and different grades of glioma tissues were stained with galectin-9-specific monoclonal antibodies. Representative patterns of galectin-9 expression in brain tissues and different grades of glioma (magnification, ×200). (B) Plot of the scores of galectin-9 expression vs. WHO grade of glioma and IR scores of different grades of glioma (brain tissue, 2.480±0.1855, n=5; glioma grade II–III, 6.880±0.2704, n=20; and glioma grade IV, 9.260±0.3899, n=20). (C and D) Association between galectin-9 in glioma tissues and Tim-3 expression in (C) CD4+ and (D) CD8+ T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. P-values were determined by Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman's correlation analysis, ***P<0.001.. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. WHO, World Health Organisation; IR, immunoreactive score; Tim-3, T cell immunoglobulin- and mucin-domain-containing molecule 3; CD, cluster of differentiation.

Discussion

Tim-3 is a receptor expressed on Th1 cells and CD8+ T cytotoxic type 1 cells (18). Galectin-9 was identified as a ligand of Tim-3, and is expressed by numerous cells (7). Galectin-9 expression may be induced by interferon (IFN)-γ from numerous tissue types (19,20). When galectin-9 binds to Tim-3 the apoptosis of T cells may be induced (18) and T cell responses may be inhibited (21). The Tim-3-galectin-9 pathway is considered to be a negative regulator for T cell-mediated immune responses (22). The present study investigated the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 in glioma tissues and identified an association between the expression of Tim-3 and galectin-9 and the malignancy of gliomas.

In general, the glioma environment may remold and immunoedit immune cells that infiltrate the tumor, resulting in the tumor cells escaping from immune surveillance (23). Several mechanisms of tumor cell immune evasion have been studied. One mechanism is the expression of immune checkpoint molecules on activated T cells infiltrating the tumor, including PD-1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 and Tim-3 (24). Tim-3 is often co-expressed with PD-1 on exhausted T cells, which are T cells with a decreased ability to express cytotoxic cytokines, including IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, when they are continuously exposed to antigens (22). Co-blockade of the two pathways has been demonstrated to be an effective way of reversing the exhaustion of CD8+ T cells (25). Tim-3 may be highly upregulated on tumor-infiltrated-lymphocytes compared with T cells in the peripheral blood of tumors (26,27). In addition, the present study detected a low expression level of Tim-3 on healthy PBMCs, and a low expression of galectin-9 on non-cancerous brain tissues. However, Tim-3 and galectin-9 were expressed at an increased level in TILs and glioma tissues, respectively, and the expression was associated with tumor malignancy. The present study suggests that malignant tumors may create an immunosuppressive environment by increasing the expression of immunosuppressive molecules, including galectin-9, in tumors. When activated T cells infiltrate the tumors, the interaction of Tim-3 on T cells with galectin-9 expressed by tumors induces dysfunction or exhaustion of the tumor-infiltrating T cells.

Tumor progression is a complex process with numerous genes and multiple signaling pathways becoming activated. It is challenging to identify particular molecules that are associated with the severity of the clinical diagnosis and prognosis of glioma. The KPS score is widely used to evaluate the severity of glioma (16). The present study investigated the correlation between the Tim-3 expression on TILs and the KPS score. The expression of Tim-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was negatively correlated with the KPS score. This data indicates that Tim-3 may be involved in the progression of glioma.

Glioma is a fatal disease of the nervous system, and there are numerous challenges in treating this disease. Immunotherapy is a promising method for the treatment of malignant tumors (28). However, the mechanism by which glioma cells escape immunological surveillance is unknown, and therefore it is critical to identify efficient immune methods to treat the disease. The present study systemically investigated the expression of Tim-3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in TILs, the expression of the Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 in glioma tissue, and the association of these two proteins with tumor malignancy and clinical pathological characteristics of patients. The data from the present study suggests that Tim-3-galectin-9 signaling may be a critical pathway in the immunoevasion of glioma cells. A blockade of the Tim-3 pathway may delay the exacerbation of glioma and enhance the KPS score, therefore improving clinical symptoms and prolonging the life of the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Xuexiang Du from the Key Laboratory of Infection and Immunity, Institute of Biophysics, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China), for technical assistance. The present study was finished under the guidance of Professor SD Wang, and was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81302200).

References

- 1.Liu Y, Shete S, Hosking F, Robertson L, Houlston R, Bondy M. Genetic advances in glioma: Susceptibility genes and networks. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okada H, Kohanbash G, Zhu X, Kastenhuber ER, Hoji A, Ueda R, Fujita M. Immunotherapeutic approaches for glioma. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:1–42. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v29.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flies DB, Sandler BJ, Sznol M, Chen L. Blockade of the B7-H1/PD-1 pathway for cancer immunotherapy. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84:409–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koguchi K, Anderson DE, Yang L, O'Connor KC, Kuchroo VK, Hafler DA. Dysregulated T cell expression of TIM3 in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1413–1418. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu C, Anderson AC, Schubart A, Xiong H, Imitola J, Khoury SJ, Zheng XX, Strom TB, Kuchroo VK. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1245–1252. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ju Y, Hou N, Meng J, Wang X, Zhang X, Zhao D, Liu Y, Zhu F, Zhang L, Sun W, et al. T cell immunoglobulin- and mucin-domain-containing molecule-3 (Tim-3) mediates natural killer cell suppression in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2010;52:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemke D, Pfenning PN, Sahm F, Klein AC, Kempf T, Warnken U, Schnölzer M, Tudoran R, Weller M, Platten M, Wick W. Costimulatory protein 4IgB7H3 drives the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma by mediating immune escape and invasiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:105–117. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wainwright DA, Chang AL, Dey M, Balyasnikova IV, Kim CK, Tobias A, Cheng Y, Kim JW, Qiao J, Zhang L, et al. Durable therapeutic efficacy utilizing combinatorial blockade against IDO, CTLA-4, and PD-L1 in mice with brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5290–5301. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Groot CJ, Montagne L, Janssen I, Ravid R, Van Der Valk P, Veerhuis R. Isolation and characterization of adult microglial cells and oligodendrocytes derived from postmortem human brain tissue. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2000;5:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1385-299X(99)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olah M, Raj D, Brouwer N, De Haas AH, Eggen BJ, Den Dunnen WF, Biber KP, Boddeke HW. An optimized protocol for the acute isolation of human microglia from autopsy brain samples. Glia. 2012;60:96–111. doi: 10.1002/glia.21251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT, Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, Linn SC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Hauptmann M, et al. A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack PC, Redman MW, Chansky K, Williamson SK, Farneth NC, Lara PN, Jr, Franklin WA, Le QT, Crowley JJ, Gandara DR. SWOG: Lower osteopontin plasma levels are associated with superior outcomes in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy: SWOG Study S0003. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4771–4776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, He S, Tu Y, Ji P, Zong J, Zhang J, Feng F, Zhao J, Gao G, Zhang Y. Downregulation of chromatin remodeling factor CHD5 is associated with a poor prognosis in human glioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji Y, Wei Y, Wang J, Ao Q, Gong K, Zuo H. Decreased expression of microRNA-107 predicts poorer prognosis in glioma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4461–4466. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monney L, Sabatos CA, Gaglia JL, Ryu A, Waldner H, Chernova T, Manning S, Greenfield EA, Coyle AJ, Sobel RA, et al. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;415:536–541. doi: 10.1038/415536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asakura H, Kashio Y, Nakamura K, Seki M, Dai S, Shirato Y, Abedin MJ, Yoshida N, Nishi N, Imaizumi T, et al. Selective eosinophil adhesion to fibroblast via IFN-gamma-induced galectin-9. J Immunol. 2002;169:5912–5918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park WS, Jung WK, Park SK, Heo KW, Kang MS, Choi YH, Kim GY, Park SG, Seo SK, Yea SS, et al. Expression of galectin-9 by IFN-γ stimulated human nasal polyp fibroblasts through MAPK, PI3K, and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ungerer C, Quade-Lyssy P, Radeke HH, Henschler R, Königs C, Köhl U, Seifried E, Schüttrumpf J. Galectin-9 is a suppressor of T and B cells and predicts the immune modulatory potential of mesenchymal stromal cell preparations. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:755–766. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson AC, Anderson DE, Bregoli L, Hastings WD, Kassam N, Lei C, Chandwaskar R, Karman J, Su EW, Hirashima M, et al. Promotion of tissue inflammation by the immune receptor Tim-3 expressed on innate immune cells. Science. 2007;318:1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1148536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rolle CE, Sengupta S, Lesniak MS. Mechanisms of immune evasion by gliomas. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;746:53–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3146-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson AC. Tim-3, a negative regulator of anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, Kuchroo V, Zarour HM. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2175–2186. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2187–2194. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devêvre E, Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, Wieckowski S, Bouzourene H, Deplancke B, Romero P, et al. Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2350–2360. doi: 10.1172/JCI46102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calinescu AA, Kamran N, Baker G, Mineharu Y, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG. Overview of current immunotherapeutic strategies for glioma. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:1073–1104. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]