Abstract

Anterior gradient protein 2 (AGR2) has been reported as a novel biomarker with a potential oncogenic role. However, its association with the prognosis and survival rate of gastric cancer (GC) has not yet been determined. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the expression and prognostic significance of AGR2 in patients with GC. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze AGR2 and cathepsin D (CTSD) protein expression in 436 clinicopathologically characterized GC cases and 92 noncancerous tissue samples. AGR2 and CTSD expression were both elevated in GC lesions compared with noncancerous tissues. In 204/436 (46.8%) GC patients, high expression of AGR2 was positively correlated with the expression of CTSD (r=0.577, P<0.01). Furthermore, several clinicopathological parameters were significantly associated with AGR2 expression level, including tumor size, depth of invasion and TNM stage (P<0.05). Using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, it was determined that the mean survival time of patients with low levels of AGR2 expression was significantly longer than those with high ARG2 expression (in stages I, II and III; P<0.05). For stage IV disease, no significant difference in survival time was identified. Multivariate survival analysis demonstrated that AGR2 was an independent prognostic factor and was associated in the progression of GC. The findings of the present study indicate that AGR2 expression is significantly associated with location and size of GC, depth of invasion, TNM stage, lymphatic metastasis, vessel invasion, distant metastasis, Lauren's classification, high CTSD expression and poor prognosis. Thus, AGR2 may be a novel GC marker and may present a potential therapeutic target for GC.

Keywords: anterior gradient protein 2, cathepsin D, gastric cancer, immunohistochemistry, progression, poor survival

Introduction

Despite continuously improving therapies, gastric cancer (GC) still has the second highest mortality rate of all tumor cases in China, with a 5-year survival rate of ~20% (1). The incidence of GC is ~934,000, with 41% of new cases diagnosed in China (2). In 2008, GC was ranked second in men and fourth in women in terms of incidence, and the second in men and third in women for mortality in China (3). Due to its asymptomatic character and lack of specific symptoms in the early stages, GC is often diagnosed in the later stage of the disease (III or IV) with high rates of lymph node metastasis (4). This leads to its poor prognosis. Invasion and metastasis are regulated at multiple molecular levels and by angiogenesis factors (5). Considering that GC is, at present, a largely incurable malignant disease, improved understanding of cancer cells is essential for the development of novel detection and therapeutic strategies.

Anterior gradient 2 (AGR2) protein is elevated in numerous types of cancer, including breast (6,7), lung (8), ovarian (9), esophageal (10), prostate (11) and pancreatic cancer (12), and was reported to be associated the metastatic phenotype and poor prognosis of breast cancer (6). However, the association between AGR2 expression, and prognosis and survival in GC remains largely unknown.

Cathepsin D (CTSD) is a common aspartic lysosomal endopeptidase. Its overexpression is positively associated with gastric carcinoma (13–15), melanoma (16), ovarian cancer (17) and colorectal cancer (18). CTSD levels were reported to be higher in tumors compared with in adjacent noncancerous tissue in colorectal cancer (19,20). Furthermore, CTSD was reported to degrade and remodel the basement membrane and interstitial stroma surrounding primary breast cancer tumors (21), and stimulate apoptotic caspases or cooperate with tumor associated pathogenic lysosomal cysteine cathepsins (22). In addition, AGR2 was reported to promote in vitro and in vivo dissemination of cancer cells through posttranscriptional induction of two proteases, cathepsin B and CTSD (12).

The present study was conducted to investigate the expression of AGR2, and its association with the progression and prognosis of patients with GC. The potential association between AGR2 and CTSD expression in GC cancer progression was also analyzed. AGR2 expression was detected and positively associated with the CTSD expression level and specific clinicopathological parameters of patients with GC.

Patients and methods

Patient collection and sample preparation

The procedures of patient collection and sample preparation were described previously (23,24). There were a total of 528 samples (436 cancer samples and 92 adjacent noncancerous tissue samples) collected during gastrectomies performed at the Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital (Hangzhou, China).

Construction of tissue microarray

Sample preparation was performed as previously described (25,26). Briefly, core tissue biopsies (2 mm in diameter) were obtained/sampled from each individual paraffin-embedded gastric tumor sample (donor blocks) and arranged in recipient paraffin blocks (tissue array blocks) using a trephine, as a previous study indicated that staining results obtained from different intratumoral areas in various tumors correlate well (27). Cases in which the tumor occupied >10% of the core area were selected for further investigation (28). Each block contained >3 internal controls consisting of nonneoplastic gastric mucosa. Sections (4-µm thick) were cut from each tissue array block, deparaffinized and dehydrated.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was performed for detecting AGR2 and CTSD in 528 tissues (with 92 control samples and 436 GC samples) (29,30). The procedures were performed using an EnVision kit (K4011 HRP, Rabbit (DAB+); Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) in accordance with previous studies (23,24). In brief, the slides were baked overnight at 60°C, followed by deparaffinization with xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohol. The sections were submerged into EDTA (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and microwaved for 10 min for antigenic retrieval. Subsequently, 3% hydrogen peroxide (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in methanol was used to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) to block nonspecific binding. Sections were incubated with anti-human rabbit monoclonal anti-AGR2 (cat. no. 2533-1; 1:500) and anti-CTSD antibodies (cat. no. 2487-1; 1:750) (Epitomics, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Normal goat serum (10000C; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used as a negative control. Subsequent to rinsing with phosphate buffer (pH=7.2) three times, the slides were incubated with the secondary antibody (EnVision kit; Dako) for 20 min at room temperature and stained with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). All the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories, Inc.), dehydrated and mounted with a coverslip using a standard medium. The slides were visualized using the Axioskop 40 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany Two independent observers, who were blinded to the study design, were employed to review the results and score all of the samples, as previously described (23). The staining intensity was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (weak staining, light yellow), 2 (moderate staining, yellow brown) and 3 (strong staining, brown), and the proportion of stained tumor cells was classified as 0 (≤5% positive cells), 1 (6–25% positive cells), 2 (26–50% positive cells) and 3 (≥51% positive cells). The expression of both proteins was considered low if the product of the staining intensity and proportion of stained tumor cells scores was ≤3 and high if the product was ≥4.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS software (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Measurement data were analyzed using the Student's t-test, whereas χ2 or Fisher's exact tests were used to examine the correlation between AGR2 and CTSD expression, and their clinicopathological parameters. Furthermore, Spearman's rank correlation tests were used to analyze the association between AGR2 and CTSD expression. Comparisons between survival curves, which were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, were performed by univariate survival analysis using the log-rank test. The prognostic value of AGR2 and CTSD expression were assessed by stepwise multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. In addition, correlation coefficients between protein expression levels and clinicopathological findings were estimated using the Pearson correlation method. Variables that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in the model with backward Cox regression (the Wald method). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

AGR2 and CTSD expression are significantly higher in GC compared with adjacent noncancerous tissue

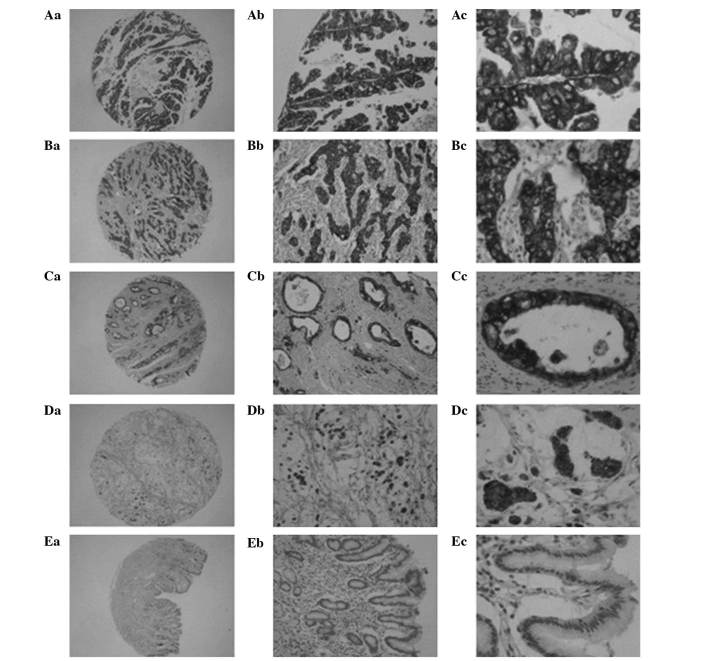

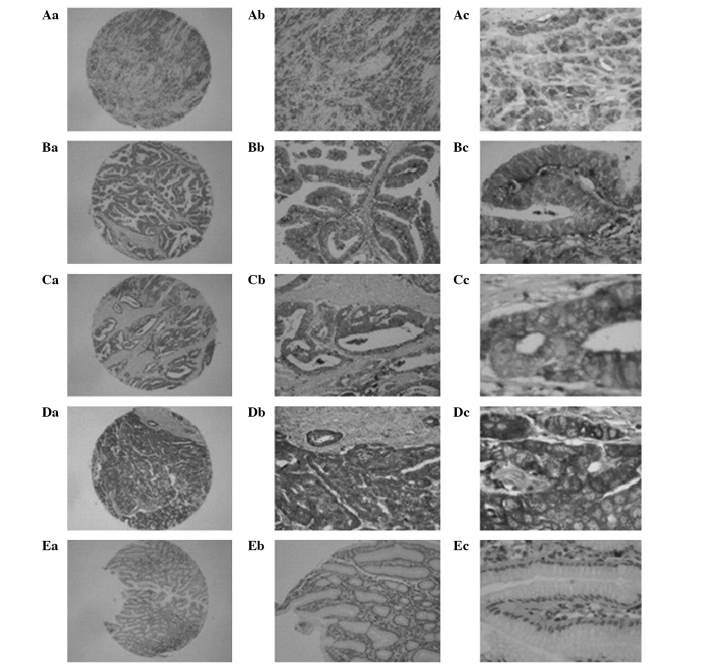

AGR2 was detected by IHC in 228/436 (52.3%) cases of GC, with 204 (46.8%) classified as high expression. By contrast, only 29 (31.5%) cases exhibited AGR2 expression in the noncancerous control group, all of which were classified as low expression. The IHC results indicated that AGR2 was predominantly located in the cytoplasm of GC cells (Fig. 1). Its expression was significantly higher in GC samples compared with control samples (P<0.05; data not shown). As expected, expression of CTSD was detected in 215/436 (49.3%) GC samples, with 138 (31.7%) exhibiting high expression. Only 27 (29.3%) cases of AGR2 expression were detected in the control group, all of which were low expression. CTSD was predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm in a similar manner to AGR2 (Fig. 2). Its expression was significantly higher in GC samples compared with the noncancerous control samples (P<0.05; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for anterior gradient protein 2 in gastric cancer and non-cancerous adjacent (EnVision method). (Aa-Ac) Strong staining in moderately differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma; (Ba-Bc) strong staining in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; (Ca-Cc) strong staining in moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; (Da-Dc) strong staining in mucinous adenocarcinoma; and (Ea-Ec) no staining in non-cancerous gastric mucosa. Original magnification: ×40 (Aa-Ea), ×100 (Ab-Eb), and ×400 (Ac-Ec).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for cathepsin D in gastric cancer and non-cancerous adjacent tissue (EnVision method). (Aa-Ac) Strong staining in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; (Ba-Bc) moderate staining in papillary adenocarcinoma; (Ca-Cc) strong staining in moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; (Da-Dc) strong staining in poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma; (Ea-Ec) and non-cancerous gastric mucosa, poor staining in stromal cells, and no staining in columnar epithelium. Original magnifications: ×40 (Aa-Ea), ×100 (Ab-Eb) and ×400 (Ac-Ec).

High AGR2 expression and CTSD expression are correlated in gastric cancer

High coincidental expression of AGR2 and CTSD in GC samples. Of the 204 patients with high expression of AGR2, 152 (74.5%) exhibited high expression of CTSD. The correlation was statistically significant (r=0.577, P<0.01).

AGR2 and CTSD are associated with clinicopathological parameters

The Pearson correlation method was used to determine the association between AGR2 and CTSD expression with clinicopathological parameters of patients with GC. The results indicated that AGR2 was significantly associated with location of the tumor, tumor size, depth of invasion, TNM stage, Lauren's classification, vessel invasion, lymphatic metastasis, regional lymph nodes and distant metastasis of tumor (P<0.05; Table I); however, no significant correlation was identified with gender, age, grade of differentiation and histological type of the tumor (P>0.05; Table I). Furthermore, GC patients with deep tumor invasion (T3 and T4), high TNM stage (stages III and IV), vessel invasion, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis exhibited significantly higher expression of AGR2 compared to those with superficial tumor invasion (T1 and T2), low TNM stage (stages I and II), and no vessel invasion, lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis (Table I). The associations between the clinicopathological parameters and CTSD expression were consistent with those of AGR2.

Table I.

Association of AGR2 and CTSD expression with clinicopathological parameters of patients with gastric cancer.

| High AGR2 expression | High CTSD expression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological parameter | Total patients, n | n (%) | t/χ2/r-valuea | P-value | n (%) | t/χ2/r-valuea | P-value |

| Gender | 0.556 | 0.456 | 0.148 | 0.700 | |||

| Male | 311 | 142 (45.7) | 138 (44.4) | ||||

| Female | 125 | 62 (49.6) | 58 (46.4) | ||||

| Age range, years | 3.632 | 0.057 | 3.401 | 0.065 | |||

| ≤60 | 237 | 101 (42.6) | 97 (40.9) | ||||

| >60 | 199 | 103 (51.8) | 99 (49.7) | ||||

| Location of tumor | 6.906 | 0.032 | 9.798 | 0.007 | |||

| Cardia | 55 | 34 (61.8) | 34 (61.8) | ||||

| Body | 163 | 78 (47.9) | 77 (47.2) | ||||

| Antrum | 218 | 92 (42.2) | 85 (39.0) | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | 23.336 | <0.001 | 22.176 | <0.001 | |||

| <5 | 256 | 95 (37.1) | 91 (35.5) | ||||

| ≥5 | 180 | 109 (60.0) | 105 (58.3) | ||||

| Depth of invasion | 70.250 | <0.001 | 71.524 | <0.001 | |||

| T1 | 57 | 4 (7.0) | 4 (7.0) | ||||

| T2 | 109 | 36 (33.0) | 33 (30.3) | ||||

| T3 | 244 | 143 (58.6) | 137 (56.1) | ||||

| T4 | 26 | 21 (80.8) | 22 (84.6) | ||||

| TNM stage | 168.125 | <0.001 | 132.672 | <0.001 | |||

| I | 90 | 5 (5.6) | 8 (8.9) | ||||

| II | 104 | 21 (20.2) | 22 (21.2) | ||||

| III | 173 | 118 (68.2) | 110 (63.6) | ||||

| IV | 69 | 60 (87.0) | 56 (81.2) | ||||

| Vessel invasion | 93.143 | <0.001 | 61.702 | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 183 | 36 (19.7) | 42 (23.0) | ||||

| Positive | 253 | 168 (66.4) | 154 (60.9) | ||||

| Lymphatic metastasis | 108.752 | <0.001 | 89.160 | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 166 | 25 (15.1) | 27 (16.3) | ||||

| Positive | 270 | 179 (66.3) | 169 (62.6) | ||||

| Regional lymph nodes | 126.361 | <0.001 | 100.981 | <0.001 | |||

| PN0 | 166 | 25 (15.1) | 27 (16.3) | ||||

| PN1 | 136 | 74 (54.4) | 73 (53.7) | ||||

| PN2 | 99 | 74 (74.7) | 67 (67.7) | ||||

| PN3 | 35 | 31 (88.6) | 29 (82.9) | ||||

| Distant metastasis | 38.614 | <0.001 | 39.265 | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 375 | 153 (40.8) | 146 (38.9) | ||||

| Positive | 61 | 51 (83.6) | 50 (82.0) | ||||

| Lauren's classification | 153.612 | <0.001 | 113.254 | <0.001 | |||

| Intestinal | 166 | 40 (17.9) | 45 (27.1) | ||||

| Diffuse | 270 | 164 (77.0) | 151 (55.9) | ||||

| Grade of differentiation | 5.285 | 0.152 | 4.782 | 0.188 | |||

| Well | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 3 (23.1) | ||||

| Moderately | 128 | 58 (45.3) | 62 (48.4) | ||||

| Poorly | 293 | 143 (48.8) | 131 (44.7) | ||||

| Not | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Histological type | 3.671 | 0.299 | 5.059 | 0.168 | |||

| Papillary | 16 | 9 (56.2) | 9 (56.2) | ||||

| Tubular | 326 | 148 (45.4) | 143 (43.9) | ||||

| Mucinous | 29 | 18 (62.1) | 18 (62.1) | ||||

| Signet-ring cell | 65 | 29 (44.6) | 26 (40.0) | ||||

Calculated using Student's t-test, χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. AGR2, anterior gradient protein 2; CTSD, cathepsin D.

AGR2 and CTSD expression are associated with prognosis

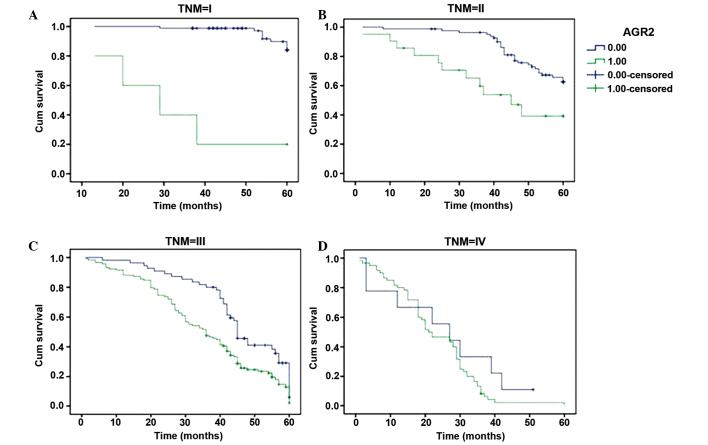

GC patients with low AGR2 expression had a significantly longer mean survival time (52.9 months) compared with those patients exhibiting high AGR2 expression (32.4 months). In agreement with this result, the 3- and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 90.9 and 57.3% versus 36.9 and 5.7%, respectively. These results indicated that high expression of AGR2 was correlated with significantly poorer prognosis compared with those exhibiting low AGR2 expression (P<0.05). Furthermore, the results of CTSD were in line with AGR2 regarding to mean survival time and 3- and 5-year cumulative survival rate. In addition, factors significantly associated with survival were assessed using univariate analysis, and it was found that age, tumor size, location, depth of invasion, TNM stage, Lauren's classification, vessel invasion, and lymph node and distant metastasis were significantly related to the prognosis while histological type and grade of differentiation were not (Table II). After stratifying by TNM stage, we found that low expression of AGR2 was significantly related longer mean survival time only in stage I, II and III. In particular, there was no significant difference in survival times between low and high expression AGR2 in stage IV (Fig. 3). Multivariate analysis was employed to further determine the correlation of the clinicopathological parameters identified by univariate analysis with the survival of GC patients. The results of Cox regression model indicated that depth of invasion, vessel invasion, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, Lauren's classification, and AGR2 expression were independent prognostic factors, whereas age, location and size of tumor, TNM stage and CTSD expression were not (Table III).

Table II.

Univariate analysis of the correlation between clinicopathological parameters and survival of patients with gastric cancer.

| Cumulative survival rate, % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological parameter | 3-year | 5-year | Mean survival time, months | Z-valuea | P-value | ||

| Age range, years | 14.745 | <0.001 | |||||

| ≤60 | 74 | 44 | 45.85 | ||||

| >60 | 59 | 29 | 39.63 | ||||

| Location of tumor | 7.849 | 0.020 | |||||

| Cardia | 55 | 24 | 37.76 | ||||

| Body | 67 | 39 | 43.22 | ||||

| Antrum | 71 | 39 | 44.13 | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | 49.579 | <0.001 | |||||

| <5 | 78 | 49 | 47.50 | ||||

| ≥5 | 52 | 21 | 36.63 | ||||

| Histological type | 0.934 | 0.817 | |||||

| Papillary | 69 | 24 | 41.92 | ||||

| Tubular | 67 | 39 | 43.26 | ||||

| Mucinous | 79 | 29 | 44.35 | ||||

| Gignet-ring cell | 63 | 38 | 41.54 | ||||

| Grade of differentiation | 0.617 | 0.432 | |||||

| Well and moderately | 73 | 36 | 44.12 | ||||

| Poorly and not | 64 | 38 | 42.45 | ||||

| TNM stage | 370.398 | <0.001 | |||||

| I | 96 | 94 | 58.09 | ||||

| II | 87 | 76 | 52.97 | ||||

| III | 61 | 7 | 37.70 | ||||

| IV | 16 | 1 | 23.26 | ||||

| Depth of invasion | 135.118 | <0.001 | |||||

| T1 | 93 | 91 | 57.18 | ||||

| T2 | 82 | 62 | 50.01 | ||||

| T3 | 58 | 18 | 38.38 | ||||

| T4 | 35 | 8 | 26.85 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | 176.051 | <0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 88 | 82 | 54.23 | ||||

| Positive | 54 | 12 | 36.30 | ||||

| Distant metastasis | 141.372 | <0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 75 | 43 | 46.23 | ||||

| Positive | 29 | 3 | 23.18 | ||||

| Vessel invasion | 127.41 | <0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 90 | 70 | 52.56 | ||||

| Positive | 51 | 16 | 36.26 | ||||

| Lauren's classification | 239.586 | <0.001 | |||||

| Intestinal | 93 | 66 | 54.12 | ||||

| Diffuse | 40 | 9 | 31.56 | ||||

| AGR2 expression | 179.188 | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 91 | 57 | 52.85 | ||||

| High | 37 | 6 | 32.40 | ||||

| CTSD expression | 113.445 | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 87 | 51 | 51.12 | ||||

| High | 40 | 12 | 33.70 | ||||

Calculated using the log-rank test. AGR2, anterior gradient protein 2; CTSD, cathepsin D.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of gastric cancer patients with high and low AGR2 expression, stratified by TNM stage of the tumor (log-rank test). (A) Survival in stage I (z=40.266, P=0.000); (B) stage II (z=10.108, P=0.001); (C) stage III (z=10.396, P=0.001); and (D) stage IV (z=1.774, P=0.183) gastric cancer with low versus high AGR2 expression. Cum, cumulative; AGR2, anterior gradient protein 2.

Table III.

Multivariate analysis of the correlation between clinicopathological parameters and survival time of patients with gastric cancer.

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard error | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (>60 vs. ≤60) | −0.277 | 0.148 | 0.758 | 0.567–1.014 | 0.062 |

| Tumor location (cardia vs. others) | 0.046 | 0.204 | 1.047 | 0.702–1.563 | 0.821 |

| Tumor size (≥5 vs. <5 cm) | −0.265 | 0.151 | 0.768 | 0.571–1.032 | 0.08 |

| Lauren's classification (diffuse vs. intestinal) | −0.649 | 0.194 | 0.523 | 0.357–0.765 | 0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis (positive vs. negative) | −0.669 | 0.328 | 0.512 | 0.269–0.975 | 0.042 |

| Vessel invasion (positive vs. negative) | −0.614 | 0.205 | 0.541 | 0.362–0.809 | 0.003 |

| Distant metastasis (positive vs. negative) | −0.503 | 0.248 | 0.605 | 0.372–0.983 | 0.042 |

| TNM stage (stages III and IV vs. I and II) | 0.263 | 0.375 | 1.300 | 0.624–2.711 | 0.483 |

| Depth of invasion (T3, T4 vs. T1, T2) | −0.724 | 0.268 | 0.485 | 0.287–0.819 | 0.007 |

| AGR2 expression (high vs. low) | −0.805 | 0.189 | 0.447 | 0.309–0.647 | <0.001 |

| CTSD expression (high vs. low) | −0.215 | 0.168 | 0.806 | 0.580–1.121 | 0.201 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; AGR2, anterior gradient protein 2; CTSD, cathepsin D.

Discussion

As a p52 suppressor inhibitor, AGR2 has been widely investigated in several types of human carcinogenesis (6–12); however, its exact functions and regulation have been largely unclear. In the present study, microarray tissue samples were initially used to evaluate the protein expression of AGR2 and CTSD in GC patients and its prognostic implications. Increased AGR2 expression in GC tissues was detected compared with adjacent noncancerous tissue. Significant associations were identified between AGR2 and location and size of tumor, TNM stage, depth of invasion, vessel invasion, lymph node and distant metastasis and Lauren's classification. Patients in late TNM stages (III and IV), with deep invasion (T3 and T4), presence of vessel invasion, and lymph node and distant metastasis exhibited the highest level of AGR2. These findings indicate that upregulation of AGR2 was involved in the progression of GC.

AGR2 is known as a stimulator of cancer cell proliferation, invasion and survival, chemotherapy resistance, metastasis and tumor growth (6,7,9,11,12). Secretion of AGR2 was been reported to correlate with metastasis and poor prognosis in breast cancer, and considered as a biomarker in prostate cancer (31–33). AGR2 upregulation was also detected in pancreatic carcinoma tissues (34,35). In GC tissues, higher expression in GC cells has previously been reported to be evident in the cytoplasm compared with non-tumor cells (36). Notably, AGR2 can be used as a suitable candidate gene for the detection of circulating tumor cells, a novel resource to identification of molecular markers, in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (37,38).

To the best of our knowledge, prognostic factors of GC includes invasion depth, TNM stage, and lymph node and distant metastasis (39). In the present study, AGR2 was identified as a novel independent prognostic factor that was significantly associated with poor prognosis in patients with GC. The current study also revealed that low expression of AGR2 was significantly associated with longer mean survival time in TNM stages I, II and III.

AGR2 shares structural characteristics with the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family. The PDI family has important roles on the cell surface, as the majority of surface proteins contain disulfide bonds in which they can modulate the activity of membrane receptors (and thus activate and regulate signaling pathways), adhesion molecules integrins, or even proteases, such as ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (40–45).

The current findings also indicated significant positive correlation between the expression of AGR2 and CTSD in GC tissues. In agreement with AGR2 expression, CTSD, which is known as an aspartic lysosomal endopeptidase, was significantly correlated with location and size of tumor, depth of invasion, vessel invasion, TNM stage, distant metastasis, lymph node metastasis, regional lymph node and Lauren's classification in the present study. Overexpression of CTSD has previously been reported in several types of human cancer, including GC (13–15), melanoma (16) and ovarian cancer (17). It may have a direct role in promoting tumor growth by basement membrane and interstitial stroma degradation and remodeling (21). Furthermore, CTSD is able to stimulate other enzymes and cooperate with certain cathepsins in the proteolysis process (22). CTSD has been reported to be upregulated by AGR2 in pancreatic cancer (12). The underlined mechanism may be the direct effect of AGR2 PDI activity in the ER during the processing of pro-cathepsins, as previously reported for the production of MUC2 in enterocytes (46).

Taken together, the present study indicated that upregulation of AGR2 may contribute to the expression of CTSD as the direct result of AGR2 PDI activity in the ER. The cross-talk of AGR2 and CTSD is possibly involved in the carcinogenesis, development and progression of GC.

The present study still has a number of limitations. First, the subjective nature of the scoring method could not be avoided and further investigation is recommended to evaluate the reproducibility of IHC scores system. Furthermore, standardization and quality control for IHC procedures is required prior to its clinical application (47).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Qinchuan Wang, Dr Jie Ma, Dr Yingyu Ma and Dr Yingjie Xia for their help and discussion with immunohistochemistry staining and statistical analysis. This study was supported by grants from the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Science and Technology Research Foundation (grant nos. 2008C33040 and 2012C33069), the Natural Scientific Research Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY14H060006) and the Natural Scientific Research Foundation of Zhejiang Medical College (grant no. 2011XZB01).

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanghai Cancer Report 2010. Shanghai: SCDC; 2010. Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WH Z, FH H. Surgical therapy of gastric cancer in china. J Pract Oncol. 2008;23:91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogenrieder T, Herlyn M. Axis of evil: Molecular mechanisms of cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2003;22:6524–6536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barraclough DL, Platt-Higgins A, de Silva Rudland S, Barraclough R, Winstanley J, West CR, Rudland PS. The metastasis-associated anterior gradient 2 protein is correlated with poor survival of breast cancer patients. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1848–1857. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D, Rudland PS, Sibson DR, Platt-Higgins A, Barraclough R. Human homologue of cement gland protein, a novel metastasis inducer associated with breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3796–3805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritzsche FR, Dahl E, Dankof A, Burkhardt M, Pahl S, Petersen I, Dietel M, Kristiansen G. Expression of AGR2 in non small cell lung cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:703–708. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park K, Chung YJ, So H, Kim K, Park J, Oh M, Jo M, Choi K, Lee EJ, Choi YL, et al. AGR2, a mucinous ovarian cancer marker, promotes cell proliferation and migration. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:91–100. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.2.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pohler E, Craig AL, Cotton J, Lawrie L, Dillon JF, Ross P, Kernohan N, Hupp TR. The Barrett's antigen anterior gradient-2 silences the p53 transcriptional response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:534–547. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300089-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang JS, Gong A, Cheville JC, Smith DI, Young CY. AGR2, an androgen-inducible secretory protein overexpressed in prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43:249–259. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumartin L, Whiteman HJ, Weeks ME, Hariharan D, Dmitrovic B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Brentnall TA, Bronner MP, Feakins RM, Timms JF, et al. AGR2 is a novel surface antigen that promotes the dissemination of pancreatic cancer cells through regulation of cathepsins B and D. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7091–7102. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allgayer H, Babic R, Grützner KU, Beyer BC, Tarabichi A, Schildberg Wilhelm F, Heiss MM. An immunohistochemical assessment of cathepsin D in gastric carcinoma: its impact on clinical prognosis. Cancer. 1997;80:179–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970715)80:2<179::AID-CNCR2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Manuel Casar J, Vizoso FJ, Abdel-Laa O, Sanz L, Martín A, Corte Daniela M, Bongera M, Muñiz García JL, Fueyo A. Prognostic value of cytosolyc cathepsin D content in resectable gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:16–21. doi: 10.1002/jso.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saku T, Sakai H, Tsuda N, Okabe H, Kato Y, Yamamoto K. Cathepsins D and E in normal, metaplastic, dysplastic and carcinomatous gastric tissue: An immunohistochemical study. Gut. 1990;31:1250–1255. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.11.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartenjev I, Rudolf Z, Stabuc B, Vrhovec I, Perkovic T, Kansky A. Cathepsin D expression in early cutaneous malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:599–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lösch A, Schindl M, Kohlberger P, et al. Cathepsin D in ovarian cancer: Prognostic value and correlation with p53 expression and microvessel density. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirana C, Shi H, Laing E, et al. Cathepsin D expression in colorectal cancer: From proteomic discovery through validation using western blotting, immunohistochemistry and tissue microarrays. Int J Proteomics. 2012;2012:245819. doi: 10.1155/2012/245819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adenis A, Huet G, Zerimech F, Hecquet B, Balduyck M, Peyrat JP. Cathepsin B, L and D activities in colorectal carcinomas: Relationship with clinico-pathological parameters. Cancer Lett. 1995;96:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03930-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szajda SD, Snarska J, Jankowska A, Roszkowska-Jakimiec W, Puchalski Z, Zwierz K. Cathepsin D and carcino-embryonic antigen in serum, urine and tissues of colon adenocarcinoma patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berchem G, Glondu M, Gleizes M, Brouillet JP, Vignon F, Garcia M, Liaudet-Coopman E. Cathepsin-D affects multiple tumor progression steps in vivo: Proliferation, angiogenesis and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:5951–5955. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krepela E. Cysteine proteinases in tumor cell growth and apoptosis. Neoplasma. 2001;48:332–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao ZS, Wang YY, Chu YQ, Ye ZY, Tao HQ. SPARC is associated with gastric cancer progression and poor survival of patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:260–268. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shou ZX, Jin X, Zhao ZS. Upregulated expression of ADAM17 is a prognostic marker for patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1014–1022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182592f56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HS, Lee HK, Kim HS, Yang HK, Kim WH. Tumour suppressor gene expression correlates with gastric cancer prognosis. J Pathol. 2003;200:39–46. doi: 10.1002/path.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HS, Lee HK, Kim HS, Yang HK, Kim YI, Kim WH. MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6 expressions in gastric carcinomas: Their roles as prognostic indicators. Cancer. 2001;92:1427–1434. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1427::AID-CNCR1466>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang D, Salto-Tellez M, Putti TC, Do E, Koay ES. Reliability of tissue microarrays in detecting protein expression and gene amplification in breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:79–84. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000047307.96344.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HS, Cho SB, Lee HE, Kim MA, Kim JH, Park J, Kim JH, Yang HK, Lee BL, Kim WH. Protein expression profiling and molecular classification of gastric cancer by the tissue array method. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4154–4163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolev Y, Uetake H, Iida S, Ishikawa T, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Prognostic significance of VEGF expression in correlation with COX-2, microvessel density and clinicopathological characteristics in human gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2738–2747. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizokami K, Kakeji Y, Oda S, Irie K, Yonemura T, Konishi F, Maehara Y. Clinicopathologic significance of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha overexpression in gastric carcinomas. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:149–154. doi: 10.1002/jso.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fritzsche FR, Dahl E, Pahl S, Burkhardt M, Luo J, Mayordomo E, Gansukh T, Dankof A, Knuechel R, Denkert C, et al. Prognostic relevance of AGR2 expression in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1728–1734. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zweitzig DR, Smirnov DA, Connelly MC, Terstappen LW, O'Hara SM, Moran E. Physiological stress induces the metastasis marker AGR2 in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;306:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9562-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Forootan SS, Liu D, Barraclough R, Foster CS, Rudland PS, Ke Y. Increased expression of anterior gradient-2 is significantly associated with poor survival of prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:293–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Ashfaq R, Maitra A, Adsay NV, Shen-Ong GL, Berg K, Hollingsworth MA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Kern SE, et al. Highly expressed genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas: A comprehensive characterization and comparison of the transcription profiles obtained from three major technologies. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8614–8622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Missiaglia E, Blaveri E, Terris B, Wang YH, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Lemoine NR. Analysis of gene expression in cancer cell lines identifies candidate markers for pancreatic tumorigenesis and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:100–112. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai Z, Ye Y, Liang B, Xu F, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Peng J, Shen D, Cui Z, Zhang Z, et al. Proteomics-based identification of a group of apoptosis-related proteins and biomarkers in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:375–383. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2010.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valladares-Ayerbes M, Díaz-Prado S, Reboredo M, Medina V, Iglesias-Díaz P, Lorenzo-Patiño MJ, Campelo RG, Haz M, Santamarina I, Antón-Aparicio LM. Bioinformatics approach to mRNA markers discovery for detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32:236–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smirnov DA, Zweitzig DR, Foulk BW, Miller MC, Doyle GV, Pienta KJ, Meropol NJ, Weiner LM, Cohen SJ, Moreno JG, et al. Global gene expression profiling of circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4993–4997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiraishi N, Sato K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Kitano S. Multivariate prognostic study on large gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:14–18. doi: 10.1002/jso.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson S, Rosenquist M, Knoblach B, Khosravi-Far R, Sommarin M, Michalak M. Diversity of the protein disulfide isomerase family: Identification of breast tumor induced Hag2 and Hag3 as novel members of the protein family. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;36:734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan PA, Gibbins JM. Extracellular disulfide exchange and the regulation of cellular function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:312–324. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turano C, Coppari S, Altieri F, Ferraro A. Proteins of the PDI family: Unpredicted non-ER locations and functions. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:154–163. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Couët J, de Bernard S, Loosfelt H, Saunier B, Milgrom E, Misrahi M. Cell surface protein disulfide-isomerase is involved in the shedding of human thyrotropin receptor ectodomain. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14800–14805. doi: 10.1021/bi961359w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lahav J, Gofer-Dadosh N, Luboshitz J, Hess O, Shaklai M. Protein disulfide isomerase mediates integrin-dependent adhesion. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:89–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willems SH, Tape CJ, Stanley PL, et al. Thiol isomerases negatively regulate the cellular shedding activity of ADAM17. Biochem J. 2010;428:439–450. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SW, Zhen G, Verhaeghe C, Nakagami Y, Nguyenvu LT, Barczak AJ, Killeen N, Erle DJ. The protein disulfide isomerase AGR2 is essential for production of intestinal mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6950–6955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808722106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Wasielewski R, Mengel M, Wiese B, Rüdiger T, Müller-Hermelink HK, Kreipe H. Tissue array technology for testing interlaboratory and interobserver reproducibility of immunohistochemical estrogen receptor analysis in a large multicenter trial. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:675–682. doi: 10.1309/URLK-6AVK-331U-0V5P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]