Abstract

Aim:

To characterize Staphylococcus aureus from clinical and subclinical mastitis and identify virulence factors.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred and two milk samples were collected, 143 from mastitic cattle and buffaloes 94 and 49, respectively, and 59 from apparently healthy cattle and buffaloes 35 and 24, respectively.

Results:

California mastitis test was applied and positive prevalence were 91.48% and 75.51% for cattle and buffalo with clinical mastitis and 37.14% and 45.83% for cattle and buffalo with subclinical mastitis. S. aureus was isolated from clinically mastitic cattle and buffaloes were 39.29% and 50%, respectively. While, from subclinical mastitic cattle and buffaloes were 80% and 72.73%, respectively. Hemolytic activity was assessed for S. aureus isolated from clinically and subclinical mastitic cases with prevalences of 100% and 56.25%, respectively. Thermo nuclease production from clinically and subclinical mastitic cases was 25% and 56.25%, respectively. Simplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conducted on S. aureus using 16S rRNA, clumping factor A, Panton valentine leukocidin, coagulase (Coa), alpha-hemolysin and beta-hemolysin those proved existence in 100%, 46.9%, 65.6%, 100%, 34.4%, and 43.75% of the isolates, respectively. While, multiplex PCR is utilized for detection of enterotoxins and proved that 12.5% was positive for enterotoxine Type D.

Conclusions:

It is concluded that simplex and multiplex PCR assays can be used as rapid and sensitive diagnostic tools to detect the presence of S. aureus and characterize its virulence factors that help in detection of severity of infection, distribution and stating preventive and control strategies.

Keywords: clinical and subclinical mastitis, enterotoxins, identification, Staphylococcus aureus, polymerase chain reaction, virulence factors

Introduction

Verily, Staphylococcus aureus is prevalent worldwide as a pathogen causing intra-mammary infections (IMI) in dairy cows and thus of economic significance to milk producing dairy farms, as it reduces milk quality and production. It has been found responsible for more than 80% of subclinical bovine mastitis, which may result in about $300 loss per animal [1]. Virulence factors of S. aureus are vital for the pathogenesis as well as for diagnosis of S. aureus. Clumping factor A (CLFA) is considered one of essential adhesion factors and has been identified as a virulence factor in an endocarditis model [2]. The role of coagulase (Coa) in IMI remains uncertain, but it is known that most S. aureus strains isolated from such infections in a matter of fact, coagulate bovine plasma [3]. Furthermore, S. aureus produces wide variety of exoproteins, including hemolysins that contribute to their ability to colonize and induce disease in mammalian hosts. Alpha hemolysin is cytotoxic while Beta-hemolysin is a sphingomyelinase expressed by the majority of strains isolated from IMI in bovines. It has been stated that both toxins increase S. aureus adhesion to epithelial cells of mammary gland [4,5].

S.aureus can produce one or more additional exoproteins, including toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), staphylococcal enterotoxins A to U (SEA, SEB, SEC, SED, SEE, SEG, SEH, SEI, and SEJ), the exfoliative toxins (ETA and ETB), and Panton valentine leukocidin (PVL). These toxins play a prominent role in staphylococcal food poisoning and other types of infections in humans and animals. PVL is cytotoxin that leads to leukocyte destruction and tissue necrosis [6].

Due to the limitations of cultural methods, the development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods the simplex and multiplex PCR assays can be used as a rapid and sensitive diagnostic tool to detect the presence of S. aureus, provide a promising option for the rapid identification made in hours, rather than days consumed by conventional cultural methods [7].

So, this study aimed to characterize S. aureus from clinically and subclinically mastitic cattle and buffaloes as well as detect some virulence factors such as hemolysins, thermo nuclease production, CLFA, PVL, Coa, alpha-hemolysin (Hla), Beta-hemolysin (Hlb), and enterotoxins.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval from cattle and buffalo’ owners and assurance of anonymity, witnessed by a veterinarian from the Egyptian Veterinary Medicine Authority was obtained.

Animals and samples

202 milk samples were collected as follows 143 from mastitic cattle and buffaloes 94 and 49, respectively and 59 from apparently healthy cattle and buffaloes 35 and 24, respectively, 20 ml of milk samples were collected aseptically after cleaning of udder and throwing the first milk strips.

Milk samples were tested by California mastitis test (CMT) [8].

Isolation of S. aureus according using Mannitol salt agar, Baird-Parker agar media, Vogel Johnson agar and brain heart infusion broth.

Identification and biochemical characterization of S. aureus [9].

-

Confirmation of S. aureus and detection of some virulence factors using PCR.

- DNA extraction: DNA of S. aureus was extracted for PCR analysis. For this purpose, S. aureus isolates were cultured in Mueller-Hinton broth overnight. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation for 10 min 5,000 rpm and washed in 1 mL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0; 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and recentrifuged for 10 min 14,000 rpm. Fifty microliters of lysostaphin (100 μg/mL) was added to the pellet, incubated for 10 min at 37°C and subsequently treated with 50 μL proteinase K (100 μg/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. For inactivation of proteinase K, the suspension was heated for 10 min at 100°C. Isolated DNA samples were kept at −20°C until further use [10].

- Specific primers are targeting genes of 16 S rRNA, PVL, CLFA, Coa, Hla, Hlb, and enterotoxins, nucleotide sequences as well as product size (Table-1).

- Protocol and program of each primer set used for genotyping and detection of virulence genes of S. aureus (Table-2).

Table-1.

List of primers, accession number and PCR product size.

| Primers | Nucleotide sequence | Accession no. | PCR product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 16 S rRNA | 16S rRNA F GTA GGT GGC AAG CGT TAT CC 16S rRNA R CGC ACA TCA GCG TCA G |

KM507158.1 | 228 | [11] |

| (2) PVL | PVL-F ATCATTAGGTAAAATGTCTGGACATGATCCA PVL-RGCATCAASTGTATTGGATAGCAAAAGC |

HM584707.1 | 433 | [12] |

| (3) CLFA | ClfA-F GGC TTC AGT GCT TGT AGG ClfA-R TTT TCA GGG TCA ATA TAA GC |

KJ001294.1 | 980 | [13] |

| (4) Coa | Coa –F CGA GAC CAA GAT TCA ACA AG Coa -R AAA GAA AAC CAC TCA CAT CA |

KJ746934.1 | Polymorphism 970, 910, 740, 410 | [14] |

| (5) Hla | HLA-1CTGATTACTATCCAAGAAATTCGATTG HLA-2CTTTCCAGCCTACTTTTTTATCAGT |

M90536 | 209 | [15] |

| (6) Hlb | HLB-1 GTGCACTTACTGACAATAGTGC HLB-2 GTTGATGAGTAGCTACCTTCAGT |

S72497 | 309 | [15] |

| (7) Enterotoxins | ||||

| SA-U (20) | 5’-TGTATGTATGGAGGTGTAAC-3’ Universal forward primer |

- | - | [16] |

| SA-A (18) | 5’-ATTAACCGAAGGTTCTGT-3’ Reverse primer for sea |

GQ859135.1 | 270 | |

| SA-B (18) | 5’-ATAGTGACGAGTTAGGTA-3’ Reverse primer for seb |

KC428707.1 | 165 | |

| SA-C (20) | 5’-AAGTACATTTTGTAAGTTCC-3’ Reverse primer for sec |

GQ461752.1 | 69 | |

| ENT-C (25) | 5’-AATTGTGTTTCTTTTATTTTCATAA-3’ Reverse primer for sec |

KF386012.1 | 102 | |

| SA-D (20) | 5’-TTCGGGAAAATCACCCTTAA-3’ Reverse primer for sed |

CP007455.1 | 306 | |

| SA-E (16) | 5’-GCCAAAGCTGTCTGAG-3’ Reverse primer for see |

EU604545.1 | 213 |

Hlb=Betahemolysin, Hla=Alphahemolysin, Coa=Coagulase, CLFA=Clumping factor A, PVL=Panton valentine leukocidin, PCR=Polymerase chain reaction

Table-2.

Primers list, program and protocol of each primer.

| Primer | Program | Protocol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All primers were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich, USA | |||||||

| Initial denaturation | No. of cycles | Denaturation | Annealing | Extension | Final extension | ||

| (1) 16 S rRNA | - | 30 | 95°C for 1 min | 70°C for 45 s | 72°C for 1 min | 72°C for 10 min | (1) |

| (2) PVL | - | 30 | 94°C for 30s | 55°C for 30s | 72°C 1 min | 72°C for 10 min. | (1) |

| (3) CLFA | - | 35 | 94°C for 60 sec | 57°C for 60 sec | 72°C for 1 min | 72°C for 10 min. | (1) |

| (4) Coa | 95°C for 2 min | 30 | 95°C 30s | 58°C for 2 min | 72°C for 4 min | 72°C for 7 min | (1) |

| (5) Hla and (6) Hlb | 95°C for 5 min | 30 | 94°C for 60 sec | 55°C for 30 s | 72°C for 1 min | 72°C for 10 min. | (1) |

| (7) Enterotoxins | - | 25 | 94°C for 30 s | 50°C for 30 s | 72°C for 30 s | 72°C for 2 min | (2) |

| Protocol (1) | PCR was performed in a 50μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl of template DNA (approximately 500 ng/μl), 5 μl of ×10 PCR buffer (750 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 0.1% Tween 20), 200 μM of each of the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roch Applied Science), and 50 pmol of each primert | ||||||

| Protocol (2) | PCR was performed in a 50μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl of template DNA (approximately 500 ng/μl), 5 μl of ×10 PCR buffer (750 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 0.1% Tween 20), 200 μM of each of the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roch Applied Science), and 50 pmol of each primer | ||||||

Hlb=Betahemolysin, Hla=Alphahemolysin, Coa=Coagulase, CLFA=Clumping factor A, PVL: Panton valentine leukocidin, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

Results

Table-3 shows results of tested animals, CM, obtained isolates, identified S. aureus, hemolytic activity, and thermo nuclease production.

Table-3.

Results of tested animals, CM, obtained isolates, identified S. aureus, hemolytic activity, and thermo nuclease production.

| Type of test | Clinically mastitic cases | Subclinically mastitic cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. | Cattle | Buffaloes | Total no. | Cattle | Buffaloes | |

| 143 | 94 | 49 | 59 | 35 | 24 | |

| CMTa | 123 | 86/94 (91.49%) | 37/49 (75.51%) | 24 | 13/35 (37.14%) | 11/24 (45.83%) |

| Obtained isolates on specific media | 38 | 28/86 (32.56%) | 10/37 (27%) | 21 | 10/13 (76.92%) | 11/11 (100%) |

| Biochemically identified as S. aureus | 16 | 11/28 (39.29%) | 5/10 (50%) | 16 | 8/10 (80%) | 8/11 (72.73%) |

| Hemolytic activity | ||||||

| Alpha α | 16 (100%) | 4/11 (36.4%) | 1/5 (20%) | 9 (56.25%) | 2/8 (25%) | 4/8 (50%) |

| Beta β | 7/11 (63.6%) | 4/5 (80%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Thermo nuclease production | 4/16 (25%) | 4/11 (36.36%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (56.25%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 4/8 (50%) |

CM=California mastitis, S. aureus=Staphylococcus aureus, CMT=California mastitis test

Table-4 shows confirmation of S. aureus isolates from cattle and buffaloes and molecular detection of some virulence factors by PCR using 16S rRNA, PVL, CLA coagulase gene, Hla, Hlb, and primers targeting genes of enterotoxins.

Table-4.

Confirmation of S. aureus isolates from cattle and buffaloes and molecular detection of some virulence factors by PCR using 16S rRNA, PVL, CLA coagulase gene, Hla, Hlb, and primers targeting genes of enterotoxins.

| Type of animal | No. of animals and isolates | Type of mastitis | PCR using primers to detect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA (%) | PVL (%) | CLA (%) | Coa Gene (%) | Hla (%) | Hlb (%) | Enterotoxins targeting genes | |||

| Cattle | 11 | Clinical | 11/11 (100) | 6/11 (54.54) | 6/11 (36.4) | 11/11 (100) | 4/11 (36.4) | 7/11 (63.6) | -ve |

| 8 | Subclinical | 8/8 (100) | 7/8 (87.5) | 3/8 (37.5) | 8/8 (100) | 2/8 (25) | 3/8 (37.5) | 4/8 (50%) Type D toxin | |

| Buffaloes | 5 | Clinical | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 4/5 (80) | 5/5 (100) | 1/5 (20) | 4/5 (80) | -ve |

| 8 | Subclinical | 8/8 (100) | 3/8 (37.5) | 3/8 (37.5) | 8/8 (100) | 4/8 (50) | 0 (0.0) | -ve | |

| Total | 32 | 32/32 (100) | 21/32 (65.6) | 16/32 (50) | 32/32 (100) | 11/32 (34.4) | 14/32 (43.75) | 4/32 (12.5%) | |

Hlb=Betahemolysin, Hla=Alphahemolysin, Coa=Coagulase, CLFA=Clumping factor A, PVL: Panton valentine leukocidin, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, S. aureus=Staphylococcus aureus

Statistical analysis

The prevalence to every test was calculated as the number of positive cattle divided by the number of examined cases within the specified period.

The Pearson and McNamara’s Chi-square tests were respectively used to estimate the association between the CMT, the culture results (isolation and identification), phenotypic virulence factors and to compare the phenotypically identified isolates with the genotypic molecular methods using SPSS statistic software version 17.0.

Results and Discussion

Concerning results obtained from Table-3 CMTpositive prevalences of clinically mastitic cases were91.48% and 75.51% for cattle and buffaloes, respectively, as well as of subclinical mastitic cases 37.14% and 45.83% for cattle and buffaloes, respectively. The obtained high results of CMT in clinically mastitic cattle was 91.48% gave great agreement with Joshi and Shrestha [17]. While, CMT of apparently healthy cattle indicating subclinical mastitis the prevalence was 37.14% which is nearly similar to Mahmoud [18]. The gained CMT and clinical mastitis results for buffaloes was 75.51% nearly similar to Linda et al. [19] who found that prevalence of clinically mastitic buffaloes in hygienically untrained households was 60.4%. Whilst, CMT of apparently healthy buffaloes gave 45.83% indicating subclinical mastitis this result was nearly similar to Akhtar et al. [20]. Commenting on the isolation and identification performed in Egypt, results obtained from Table-3 was conspicuous that S. aureus was higher in clinically mastitic buffaloes than cattle with prevalences of 50% and 39.29%, respectively. Whereas, identified S. aureus was higher in subclinically mastitic cattle than buffaloes with prevalences of 80% and 72.73%, respectively. It was confirmed in Egypt that S. aureus considered the predominant among mastitis causing pathogens followed by Streptococcus agalactiae [21] and Escherichia coli [22]. The identified S. aureus prevalence from clinically mastitic buffaloes was nearly similar to Hameed [23] who noted that the prevalence of clinical bovine mastitis caused by S. aureus was 53.85% in buffaloes from Tehsil Burewala Pakistan. However our result concerning the identification of S. aureus from clinically mastitic cattle 39.29% and from subclinical mastitic cattle and buffaloes 80% and 72.73% coincides with Hase et al. [24].

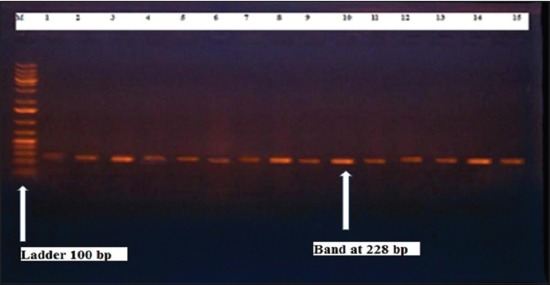

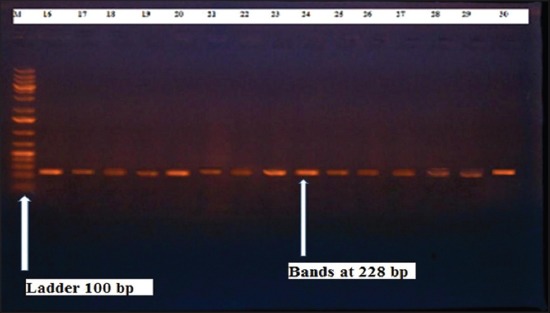

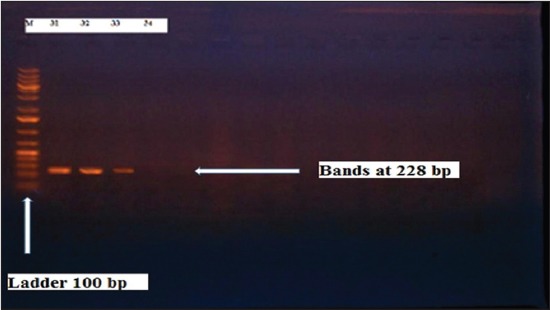

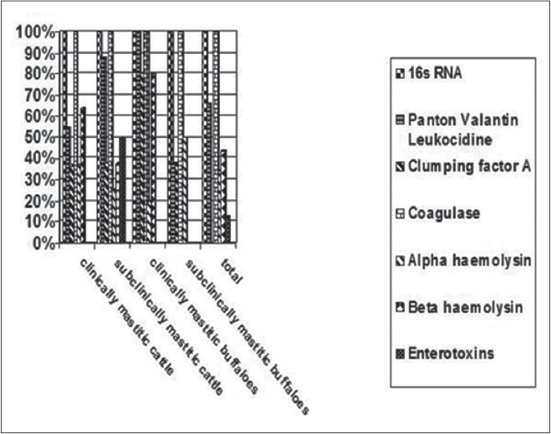

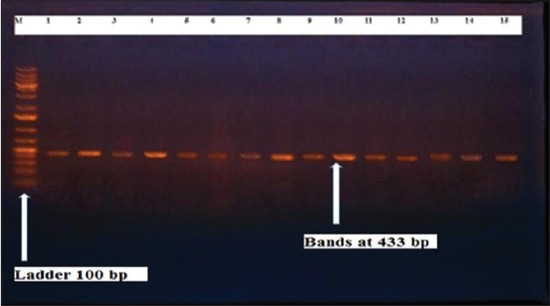

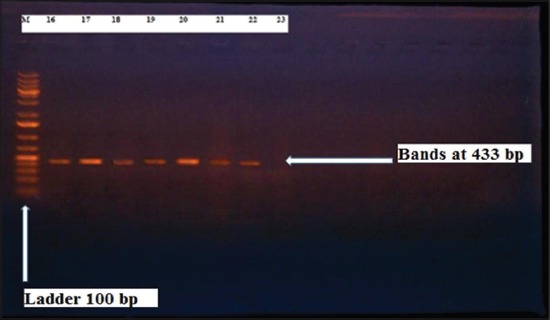

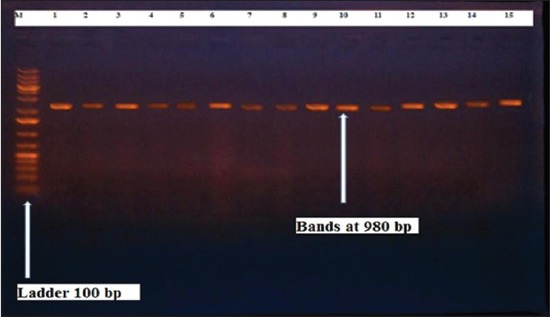

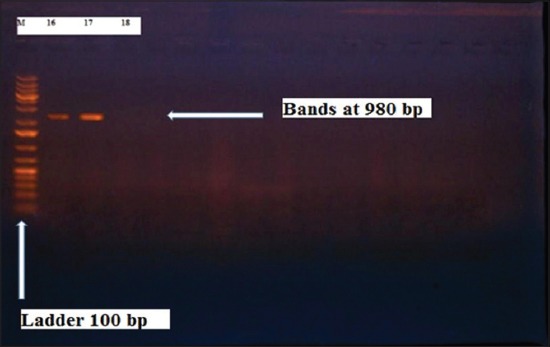

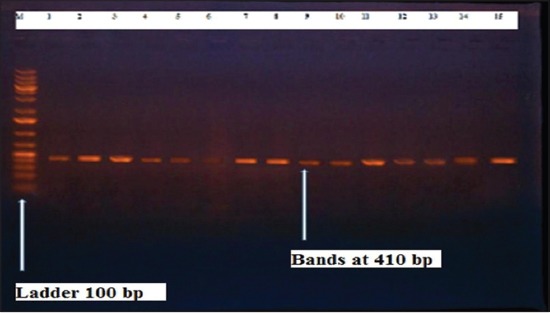

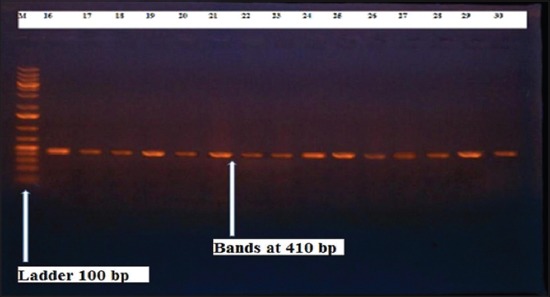

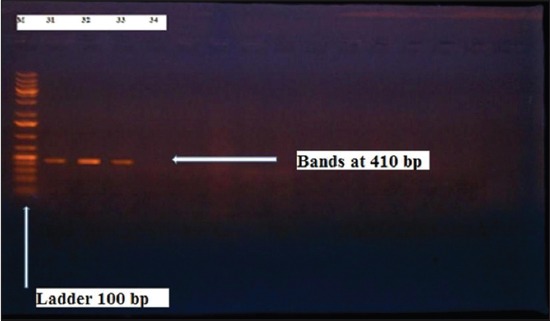

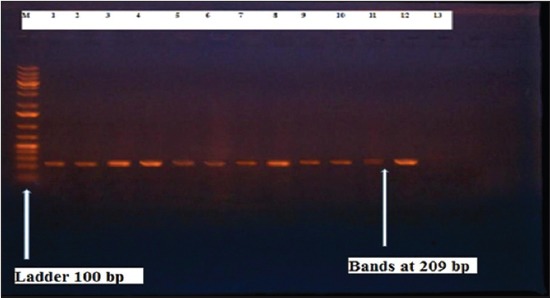

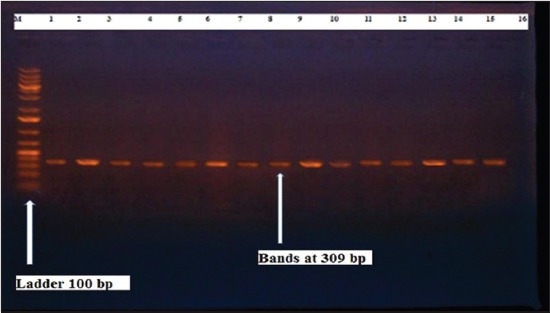

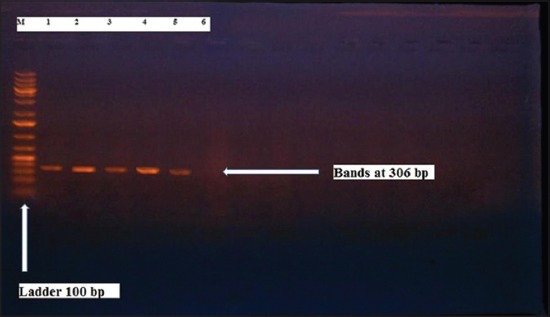

Herein, from Table-3, it is overt that the total hemolytic activity of S. aureus isolated from clinically mastitic cases was assessed and all the isolates 100% were completely hemolytic, α hemolysis results were 36.4% and 20% for cattle and buffaloes respectively. In addition to that, β hemolysis results were 63.6% and 80% for cattle and buffaloes respectively. Furthermore, the total hemolytic activity of subclinical mastitic S. aureus was 56.25%, α hemolysis results were 25% and 50% for cattle and buffaloes, respectively. Moreover, β hemolysis results were 37.5% and 0.0% for cattle and buffaloes respectively. Herby, the higher total hemolytic activity of S. aureus from clinically mastitic cases 100% [25]. Results obtained in Table-3 express the result of (TNase) produced from isolated S. aureus as follows total result of positive (TNase) production from clinically mastitic cases was 25%, but the result of subclinically mastitic cases was 56.25% our obtained results were lower than that obtained by Hamama [26]. Referring to results of Table-4 and Figures 1-4 which indicate implementation of simplex PCR for confirmation of isolates using 16S rRNA which proved that 100% of the isolates were confirmed to be S. aureus and that concurred with Monday and Bohach [11]. Focusing on detection of PVL and results of Table-4 and Figures-2-6 only 65.6% of the isolates proved the existence of PVL and that nearly similar to Unal et al. [27]. Also, putting in consideration the results of CLFA as expressed in Table-4 and Figures-4, -7 and -8, 14 about 46.9% of isolated S. aureus harbored CLFA that was nearly similar to results obtained by Momtaz et al. [28]. Concerning results in Table-4 and Figures-4, and -9-11 of simplex PCR for detection of coagulase gene Coa all isolates 100% harbored this gene this result mainly agree with the result recorded by Karakulska et al. [29]. It is apparent from Table-4 and Figures-4, -12, and -13) that there located genetic confirmation of the phenotypic hemolytic results, performed by testing the presence of Hla and Hlb genes and the existence rates were 34.4% and 43.75% within the isolates, respectively that’s basically concurred [30]. Some Staphylococci produce staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) involved in staphylococcal food poisoning syndrome in humans, especially in the TSST-1, the ETA and ETB that cause staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in children and newborns. Recently, 19 serologically distinct SEs have been identified. SEs A, B, C, D, and E are the classical five major types. However, other new enterotoxins have been described by Thomas et al. [31]. Because of the importance of these toxins in the public health and food sectors, an efficient screening to detect the prevalence of enterotoxigenic strains in foods is required, so we used multiplex PCR technique for detection of enterotoxigenic S. aureus. From Table-4 and Figures-4 and -14 only 12.5% of the tested isolates were positive for enterotoxine D, and that mainly coincides with Hamama [26]. Hence, the genotypic results of this study might help to better understand the prevalence and distribution of S. aureus clones among bovines and will help to assess control strategies for S. aureus infections [32].

Figure-1.

Results of molecular detection of Staphylococcus aureus 16S rRNA where (M is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 32) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 228 bp, moreover, lanes (33 and 34) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-2.

Results of molecular detection of Panton valentine leukocidin using where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 21) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 433 bp, moreover, lanes (22 and 23) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-3.

Results of molecular detection of Clumping factor A using where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 16) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 980 bp, moreover, lanes (17 and 18) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-4.

Collective results of genotypic detection of Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors.

Figure-5.

Results of molecular detection of Coa gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 32) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 410 bp, moreover, lanes (33 and 34) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-6.

Results of molecular detection of Hla gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 11) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 209 bp, moreover, lanes (12 and 13) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-7.

Results of molecular detection of Hlb gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 14) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 309 bp, moreover, lanes (15 and 16) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-8.

Results of molecular detection of Enterotoxine D gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 4) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 309 bp, moreover, lanes (5 and 6) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-9.

Collective results of genotypic detection of Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors.

Figure-10.

Results of molecular detection of Coa gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 32) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 410 bp, moreover, lanes (33 and 34) represent control positive and negative control respectively.

Figure-11.

Results of molecular detection of Coa gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 32) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 410 bp, moreover, lanes (33 and 34) represent control positive and negative control respectively.

Figure-12.

Results of molecular detection of HIa gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 14) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 309 bp, moreover, lanes (15 and 16) represent control positive and negative control respectively.

Figure-13.

Results of molecular detection of HIb gene where (M is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 14) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 309 bp, moreover, lanes (15 and 16) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Figure-14.

Results of molecular detection of Enterotoxine D gene where (M; is marker of 100 bp range, while lanes from (1 to 4) indicate positive isolates and result appear at 306 bp, moreover, lanes (5 and 6) represent control positive and control negative respectively.

Conclusion

It is concluded that simplex and multiplex PCR assays can be used as rapid and sensitive diagnostic tools to detect the presence of S. aureus and characterize its virulence factors that help in detection of severity of infection, distribution and stating preventive and control strategies.

Authors’ Contributions

MSE carried out the laboratory work, helped in isolation and identification of isolates, made all the molecular steps, compiled and analyzed information and data, wrote and drafted the manuscript, AEME revised the manuscript and MAD helped in sampling, isolation and identification of isolates.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the farmers and veterinarians who provided the samples used in this study, and great thanks to the administration of Genetic Engineering and biotechnology Research Institute University of Sadat city for their great help in fulfilling the molecular work in this study by providing the PCR apparatus.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Karahan M., Acik M.N., Cetinkaya B. Investigation of toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis in Turkey. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009;8:1029–1035. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heilmann C. In: Mechanisms of Staphylococci Bacterial Adhesion. Linke D., Goldman A., editors. Netherlands: Springer; 2011. pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutra L., Poutrel B. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of bovine intra-mmamary infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Med. Microbiol. 1994;40:79–89. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-2-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akineden O., Hassan A.A., Schneider E., Usleber E. A coagulase-negative variant of Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis milk. J. Dairy Res. 2011;78:38–42. doi: 10.1017/S0022029910000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt J., Joost I., Skaar E.P., Herrmann M., Bischoff M. Haemin represses the haemolytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus in an Sae-dependent manner. Microbiology. 2012;158:2619–2631. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.060129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argudin M.A., Mendoza M.C., Rodicio M.R. Food poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Toxins. 2010;2:1751–1773. doi: 10.3390/toxins2071751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J., Ferreri M., Liu X.Q., Chen L.B., Su J.L., Han B. Development of multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus and selected antibiotic resistance genes in bovine mastitic milk samples. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2011;23:894–901. doi: 10.1177/1040638711416964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radostits O.M., Gay D.C., Blood, Hinschiff K.W. London. United Kingdom: WB, Saunders. Company Ltd; 2000. Veterinary Medicine, Text Book of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn P.J., Carter M.E., Markey B.K., Carter G.R. Printed in Spain by Grafos, sa. Arte Sobre Papel. London, England: Wolfe Publishing, an Imprint of Mosby-Year Book Europe Limited; 1994. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology; pp. 327–344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unal S., Hoskins J., Flokowitsch J.E., Wu C.Y., Preston D.A., Skantrud P.L. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococci by using the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:1685–1691. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1685-1691.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monday S., Bohach G. Use of multiplex PCR to detect classical and newly described pyrogenic toxin genes in Staphylococcal Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:3411–3414. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3411-3414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lina G., Piemont Y., Godail-Gamot F., Bes M., Peter M., Gauduchon V., Vandenesch F., Etienne J. Involvement of panton –valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;29:1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephan R., Annemuller C., Hassan A.A., Lammler C. Characterization of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis in north-east Switzerland. Vet. Microbiol. 2001;78:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslantas O., Demir C., Turutoglu H., Cantekin Z., Ergun Y., Dogruer G. Coagulase gene polymorphism of Staphylococcus aureus isolated form subclinical mastitis. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2007;31:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarraud S., Mougel C., Thioulouse J., Lina G., Meugnier H., Forey F., Nesme J., Etienne X., Vandenesch F. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus Genetic background, virulence factors, AGR groups (Alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immunol. 2002;70:631–641. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.631-641.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma N.K., Rees C.E., Dodd C.E. PCR toxin typing assay for development of a single-reaction multiplex Staphylococcus aureus strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1347. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1347-1353.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi H.D., Shrestha H.K. Study on the prevalence of clinical mastitis in cattle and buffaloes under different management systems in the western hills of Nepal. Working paper. Lumle Regist. Agric. Res. Cent. 1995;4:95–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahmoud A.A. Some studies on subclinical mastitis in dairy cattle. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 1988;20:150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linda N.G., Jost C., Robyn M., Dhakal I.P., Bett E., Dhakal P., Khadkha R. Impact of livestock hygiene education programs on mastitis in small holder water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Chitwan, Nepal. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010;96:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akhtar A., Ameer H., Aeshad M. Prevalence of subclinical mastitis in buffaloes in district D. I. Khan. Pak. J. Sci. 2012;64:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elhaig M.M., Selim A. Molecular and bacteriological investigation of subclinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae in domestic bovidsfrom Ismailia, Egypt. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015;47:271–6. doi: 10.1007/s11250-014-0715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamed M.I., Ziatoun A.M.A. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus subclinical mastitis in dairy buffaloes farms at different lactation seasons at Assiut Governorate, Egypt. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2014;4:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hameed S.M., Arshad M., Ashraf M., Shahid M.A. Prevalence of common mastitogens and their antibiotic susceptibility in Tehsil Burewala, Pakistan. Pak. J. Agr. Sci. 2008;45:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hase P., Digraskar S., Ravikanth K., Dandale M., Maini S. Management of subclinical mastitis with mastilep gel and herbal spray (AV/AMS/15) Int. J. Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;4:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Jakee J.K.A., Zaki E.R., Farag R.S. Properties of enterotoxigenic S. aureus isolated from mastitic cattle and buffaloes in Egypt. J. Am. Sci. 2010;11:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamama A. Ther monuclease and enterotoxin production and biotyping of Staphylococci isolated from moroccan dairy products. Lait. 1987;67:403–411. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unal N., Askar S., Macun H.C., Sakarya F., Altun B., Yildirim M. Panton –Valentine leukocidin and some exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of staphylococci isolated from milks of small ruminants. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012;4:573–579. doi: 10.1007/s11250-011-9937-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Momtaz H., Rahimi E., Tajbakhsh E. Detection of some virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical and subclinical bovinemastitis in Iran. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:3753–3758. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karakulska J., Pobucewicz A., Nawrotek A., Muszyńska M., Furowicz A.J., Furowicz D.C. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus based on PCR-RFLP of coa gene and RAPD analysis. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2011;14:285–286. doi: 10.2478/v10181-011-0044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fei Y., Hongjun Y., Hong-Bin H., Changfa W., Yundong G., Qifeng Z., Xiahong W., Yanjun Z. Study on haemolysin phenotype and the genotype distribution of Staphylococcus aureus caused bovine mastitis in Shandong dairy farms. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 2011;9:416–421. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas D., Chou S., Dauwalder O., Lina G. Diversity in Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 2007;93:24–41. doi: 10.1159/000100856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salasia S.I.O., Tato S., Sugiyono N., Ariyanti D., Prabawati F. Genotypic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovines, humans, and food in Indonesia. J. Vet. Sci. 2011;12:353–361. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2011.12.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]