The nuclear localization of subclass I actin-depolymerizing factor is critical for the susceptibility against an adapted powdery mildew.

Abstract

Actin-depolymerizing factors (ADFs) are conserved proteins that function in regulating the structure and dynamics of actin microfilaments in eukaryotes. In this study, we present evidence that Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) subclass I ADFs, particularly ADF4, functions as a susceptibility factor for an adapted powdery mildew fungus. The null mutant of ADF4 significantly increased resistance against the adapted powdery mildew fungus Golovinomyces orontii. The degree of resistance was further enhanced in transgenic plants in which the expression of all subclass I ADFs (i.e. ADF1–ADF4) was suppressed. Microscopic observations revealed that the enhanced resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4 knockdown plants (ADF1-4Ri) was associated with the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and cell death specific to G. orontii-infected cells. The increased resistance and accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in ADF1-4Ri were suppressed by the introduction of mutations in the salicylic acid- and jasmonic acid-signaling pathways but not by a mutation in the ethylene-signaling pathway. Quantification by microscopic images detected an increase in the level of actin microfilament bundling in ADF1-4Ri but not in adf4 at early G. orontii infection time points. Interestingly, complementation analysis revealed that nuclear localization of ADF4 was crucial for susceptibility to G. orontii. Based on its G. orontii-infected-cell-specific phenotype, we suggest that subclass I ADFs are susceptibility factors that function in a direct interaction between the host plant and the powdery mildew fungus.

Powdery mildew is an obligate biotrophic fungal pathogen that infects approximately 10,000 plant species, including crops, vegetables, and ornamental plants, thus causing extensive economic losses worldwide (Takamatsu, 2004). In an effort to understand the plant response to powdery mildew fungal infection and the mechanism of plant-powdery mildew fungus interactions, many mutants of host plants, particularly the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), have been identified and analyzed.

Genes for which loss causes increased resistance to a pathogen could encode factors involved in the suppression of plant immunity or susceptibility factors that function in support of the pathogenic infection. Previously identified Arabidopsis genes, the loss of whose expression causes enhanced resistance against adapted powdery mildew fungi, include POWDERY MILDEW RESISTANT1 (PMR1) to PMR6 (Vogel and Somerville, 2000; Vogel et al., 2002, 2004; Nishimura et al., 2003), MILDEW RESISTANCE LOCUS O2 (MLO2; Consonni et al., 2006), ENHANCED DISEASE RESISTANCE1 (EDR1), EDR2, and EDR3 (Frye and Innes, 1998; Frye et al., 2001; Tang et al., 2005a, 2006), CONSTITUTIVE EXPRESSION OF VSP1 (CEV1; Ellis et al., 2002), PLANT UBIQUITIN REGULATORY X DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN2 (Chandran et al., 2009), FERONIA (FER; Kessler et al., 2010), MYB3R4 (Chandran et al., 2010), AUTOPHAGY-RELATED2 (ATG2), ATG5, ATG7, ATG10, and ATG18 (Wang et al., 2011a, 2011b), PHYTOCHROME-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE TYPE2C (PAPP2C; Wang et al., 2012), ASSOCIATED MOLECULE WITH THE SH3 DOMAIN OF STAM1 (AMSH1; Katsiarimpa et al., 2013), Arabidopsis LIFEGUARD1 (AtLFG1) and AtLFG2 (Weis et al., 2013a), LESION INITIATION2 (LIN2; Guo et al., 2013), DP-E2F-LIKE1 (DEL1; Chandran et al., 2014), and CHYTOCHROME P450 83A1 (CYP83A1; Weis et al., 2013b, 2014). Mutations in PMR5, AtLFG6, CEV1, and CYP83A1 cause modifications of cuticular wax or cell wall structure, negatively affecting the infection of powdery mildew fungi that grow and proliferate on the leaf surface. The functions of MLO, a membrane protein with seven transmembrane domains, and FER, a receptor-like kinase, are essential for the cell entry of powdery mildew fungi. The atypical E2F transcription factor DEL1 suppresses the expression of the salicylic acid (SA) transporter ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY5 and, thus, regulates the SA signaling pathway that is activated in response to powdery mildew fungus infection (Chandran et al., 2014). PAPP2C interacts with and suppresses the function of the atypical resistance protein RESISTANCE TO POWDERY MILDEW8.2 (Xiao et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2012). The transcription factor MYB3R4 activates G2/M progression, and MYB3R4-dependent endoreduplication in both powdery mildew fungus-infected epidermal cells and surrounding mesophyll cells is required to support powdery mildew growth and proliferation. EDR1, a MEK kinase, is considered to be a negative regulator of cell death, as its loss also causes enhanced cell death under various abiotic stress conditions (Tang et al., 2005b). EDR2 (a membrane-localized novel protein that contains a mitochondrial targeting sequence), EDR3 (a dynamin-related protein 1E that localizes to mitochondria), ATGs, LIN2, and AtLFGs are also considered suppressors of cell death. Many of the above-mentioned mutants exhibit a pleiotropic phenotype including accelerated senescence and cell death (Atmlo2, edr1, edr2, atgs, amsh1, and lin2) and reduced plant size (pmr3, pmr5, pmr6, cev1, atgs, papp2c, fer, lin2-2, and del1).

Plant actin microfilaments (AFs) play a key role in the plant-pathogen interaction (Takemoto and Hardham, 2004; Day et al., 2011; Higaki et al., 2011). The organization and dynamics of AFs are regulated by a number of actin-binding proteins, among which actin-depolymerizing factors (ADFs) play a conserved role in actin destabilization by severing and depolymerizing microfilaments at the minus end in eukaryotes, including yeast, mammals, and plants (Maciver and Hussey, 2002; Henty-Ridilla et al., 2013). The Arabidopsis genome contains 11 members of the ADF gene family, which are classified into four subclasses (Ruzicka et al., 2007). Subclass I, which contains ADF1 to ADF4, is expressed at a relatively high level throughout the plant. Subclass II is further divided into subclass IIa comprising ADF7 and ADF10, which are specifically expressed in mature pollen grains, and subclass IIb consisting of ADF8 and ADF11, for which expression is limited to the root epidermal cells. ADF5 and ADF9 in subclass III and ADF6 in subclass IV are expressed in a wide variety of tissues (Ruzicka et al., 2007). As in animal cells, ADFs in plants also bind to both monomeric and filamentous actins (Tian et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2013) and regulate the organization of AFs (Zheng et al., 2013; Henty-Ridilla et al., 2014).

The function of plant ADFs in plant-pathogen interactions has been studied extensively. Transient overexpression of HvADF3, AtADF1, AtADF5, AtADF6, AtADF7, and AtADF11 (called AtADF12 in this article), but not the overexpression of AtADF2, AtADF3, AtADF4, and AtADF9, partially breaks down the resistance of barley (Hordeum vulgare) mlo against the barley-adapted powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei (Bgh; Miklis et al., 2007). The localization of RPW8.2 to the membrane surrounding the powdery mildew fungal haustorium is inhibited by the overexpression of Arabidopsis ADF6 but not by the overexpression of ADF5 (Wang et al., 2009). The mutant adf4 shows increased susceptibility to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato (Pst) DC3000 avirulent strain carrying AvrPphB but not to virulent Pst or avirulent Pst DC3000 carrying AvrRpt2 or AvrB (Tian et al., 2009; Porter et al., 2012). Arabidopsis ADF2 expression is up-regulated in the giant feeding cells formed during infection by the root-knot nematode, and in plants that show a reduced ADF2 expression level, nematode growth in roots is inhibited (Clément et al., 2009). Barley rpg4-mediated resistance locus 1, which mediates resistance against the stem rust Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici race QCCJ, contains HvRga1, Rpg5, and HvAdf3, although the suppression of HvADF3 expression alone does not induce resistance against P. graminis (Wang et al., 2013). The expression of wheat (Triticum aestivum) TaADF7 is induced by infection with Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, which causes stripe rust on wheat, and suppression of TaADF7 expression causes increased susceptibility to P. striiformis f. sp. tritici (Fu et al., 2014). More recently, soybean (Glycine max) ADF2 was identified to interact with the soybean mosaic virus P3 protein, which suggests that P3 has a function in intercellular virus movement (Lu et al., 2015).

In this study, we found that the Arabidopsis adf4 mutant shows significantly increased resistance against the adapted powdery mildew fungus Golovinomyces orontii. The resistance to G. orontii was further enhanced in plants in which the expression of all four subclass I ADFs was knocked down (ADF1-4Ri). Neither adf4 nor ADF1-4Ri showed macroscopic lesions and defective plant development. The resistance in ADF1-4Ri was accompanied by infected-cell-specific hydrogen peroxide accumulation and cell death. Quantification analysis of AF organization using Arabidopsis plants expressing GFP-tagged human Talin (GFP-hTalin) revealed a significant increase in the level of bundling in ADF1-4Ri at very early time points. However, observed changes in the AF organization was unexpectedly small, considering the dramatic increase in resistance to G. orontii in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri. Microscopic analysis using transgenic plants expressing GFP-labeled ADF4 revealed that ADF4 function in the nucleus is crucial for susceptibility to G. orontii. We discuss the possible function of ADF4 in a direct interaction between the host plant and the powdery mildew fungus.

RESULTS

Loss of ADF4 Expression and Reduced Expression of All Members of ADF Subclass I Confer Enhanced Resistance against the Adapted Powdery Mildew G. orontii

Among four Arabidopsis subclass I ADFs, transfer DNA-based null mutant lines are available for ADF1 (SALK_144459), ADF3 (SALK_139265), and ADF4 (Garlic_823_A11.b.1b.Lb3Fa) but not for ADF2 (Clément et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2009). ADF3 is the most abundantly expressed, approximately 3-fold more than the other three ADFs (Ruzicka et al., 2007). To examine the function of ADFs in the plant-powdery mildew interaction, we inoculated adf1, adf3, and adf4 null mutants with Arabidopsis-adapted G. orontii.

Visual examination at 2 weeks post inoculation (wpi; Fig. 1A) indicated that the mycelial coverage on adf1 leaves was comparable to that of the wild-type Col-0. Both adf3 and adf4 showed increased resistance against G. orontii, although their phenotypes differed: adf3 leaves exhibited extensive leaf yellowing but powdery mildew mycelial coverage was not notably affected, whereas adf4 exhibited only slight leaf yellowing and markedly less mycelial coverage (Fig. 1A). Neither adf3 nor adf4 uninfected leaves showed spontaneous cell death, and infected leaves did not exhibit macroscopic lesions.

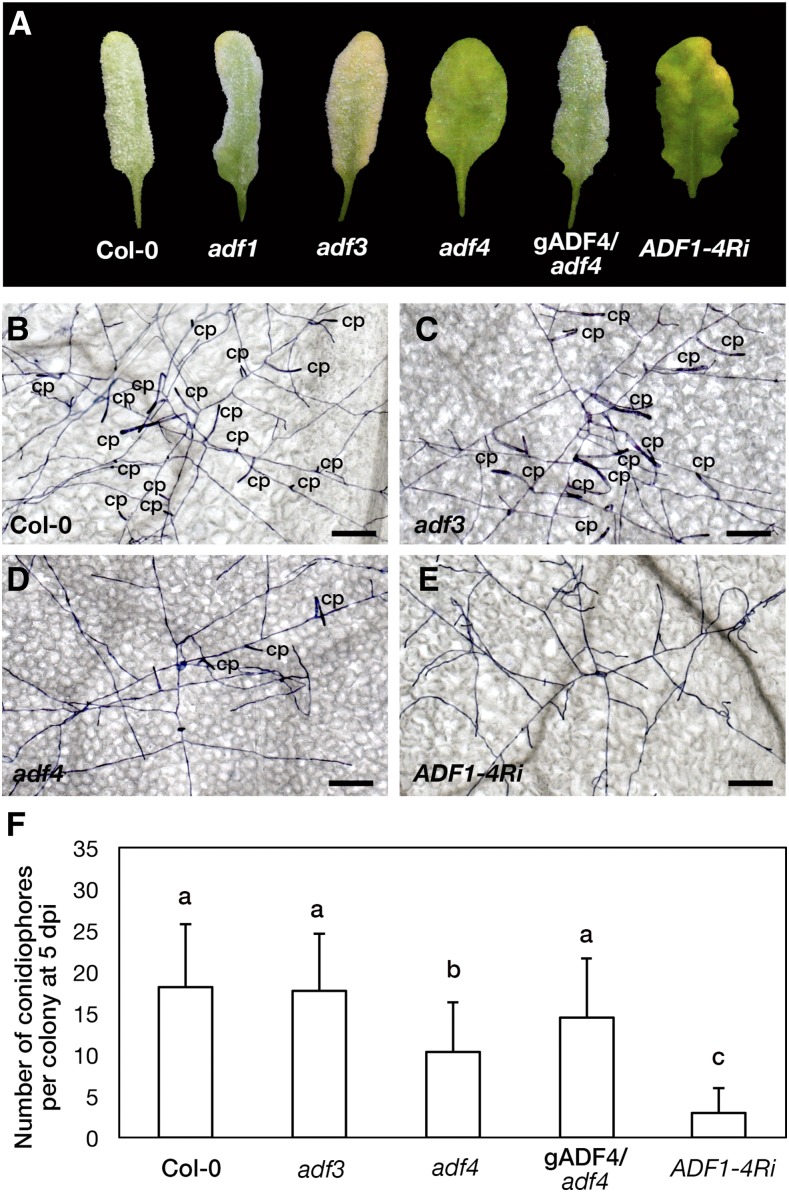

Figure 1.

Increased resistance against the adapted powdery mildew fungus G. orontii in the adf4 knockout mutant and a transgenic plant with reduced expression of subclass I ADFs. A, Leaves of Columbia-0 (Col-0), adf1, adf3, adf4, adf4 complemented with ADF4 genomic DNA including a native promoter (gADF4/adf4), and a transgenic plant in which the expression of all four members of subclass I ADFs was suppressed (ADF1-4Ri) at 2 wpi with G. orontii. B to E, Trypan Blue-stained G. orontii colonies on Col-0 (B), adf3 (C), adf4 (D), and ADF1-4Ri (E) leaves at 5 dpi. cp, Conidiophores. Bars = 100 µm. F, Number of conidiophores per colony at 5 dpi. Three independent experiments were performed and showed similar results; the results of one representative experiment are shown. Error bars indicate sd (n = 100). Comparisons between multiple groups (Col-0, adf3, adf4, gADF4/adf4, and ADF1-4Ri) were performed by ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test for each data set. The same letter indicates that there are no significant differences (P < 0.05).

To quantify G. orontii susceptibility in adf3 and adf4, we microscopically examined Trypan Blue-stained leaves at 5 d post inoculation (dpi; Fig. 1, B–D) and counted the number of conidiophores per colony (Fig. 1F). G. orontii colonies produced conidiophores on adf3 in a similar manner to those on the wild type (Col-0) at 5 dpi (Fig. 1, B, C, and F). In contrast, G. orontii produced significantly fewer conidiophores on adf4 (Fig. 1, D and F). The G. orontii-resistant phenotype in adf4 was suppressed by the expression of ADF4 genomic sequence (Fig. 1, A and F; Tian et al., 2009; Henty et al., 2011).

Transgenic ADF1-4Ri plants, in which the expression of all members of subclass I ADFs (ADF1–ADF4) is suppressed (Tian et al., 2009), were tested for susceptibility to powdery mildew. ADF1-4Ri plants showed prominently increased resistance; no visible fungal mycelia were present on the leaf surface at 2 wpi (Fig. 1A), and almost no conidiophores were produced on ADF1-4Ri leaves at 5 dpi (Fig. 1, E and F). This prominent resistance to powdery mildew was observed in all four isolated lines of ADF1-4Ri (Supplemental Fig. S1). Among those four transgenic lines, the expression of ADF1 to ADF4 was variously affected, as determined by Tian et al. (2009). We could not find any correlation between the level of suppression of ADF1 to ADF4 expression and the level of resistance against G. orontii. The penetration resistance against G. orontii was not affected in adf1, adf3, adf4, or ADF1-4Ri (Supplemental Fig. S2).

In addition to increased resistance against G. orontii, the morphology of rosette leaves was altered in both adf4 and ADF1-4Ri but not in adf3; the lamina of mature rosette leaves of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri was flatter than that of the wild type. This phenotype was more strongly manifested in ADF1-4Ri (Fig. 1A). The other aspects of plant development and growth of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri were comparable with those of the wild type. Whereas the Arabidopsis adf9 mutant shows an early-flowering phenotype (Burgos-Rivera et al., 2008), both adf4 and ADF1-4Ri plants developed inflorescences at a similar time to the wild type under the long-day condition (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Taken together, we concluded that Arabidopsis subclass I ADFs, particularly ADF4, contribute to susceptibility against powdery mildew. Consequently, we used adf4 and ADF1-4Ri plants for further analyses of their function in susceptibility to powdery mildew.

Increased Resistance of ADF1-4Ri Is Accompanied by Infected-Cell-Specific Accumulation of Hydrogen Peroxide and Cell Death

During observation of Trypan Blue-stained G. orontii colonies using a light microscope, we noticed that primary infected cells (those located near conidia) of ADF1-4Ri leaves were often darkly colored and exhibited a thicker cell wall compared with neighboring cells at 5 dpi (Fig. 2A). Cells infected by G. orontii were examined at an earlier time point using a confocal laser scanning microscope. At 3 dpi, haustoria stained with propidium iodide (PI) in primary infected cells of Col-0 leaves were fully mature and had developed lobes (Fig. 2B), but they were often disrupted in ADF1-4Ri (Fig. 2C). Similar disruption of haustoria was also observed in adf4, although at a much reduced frequency compared with ADF1-4Ri.

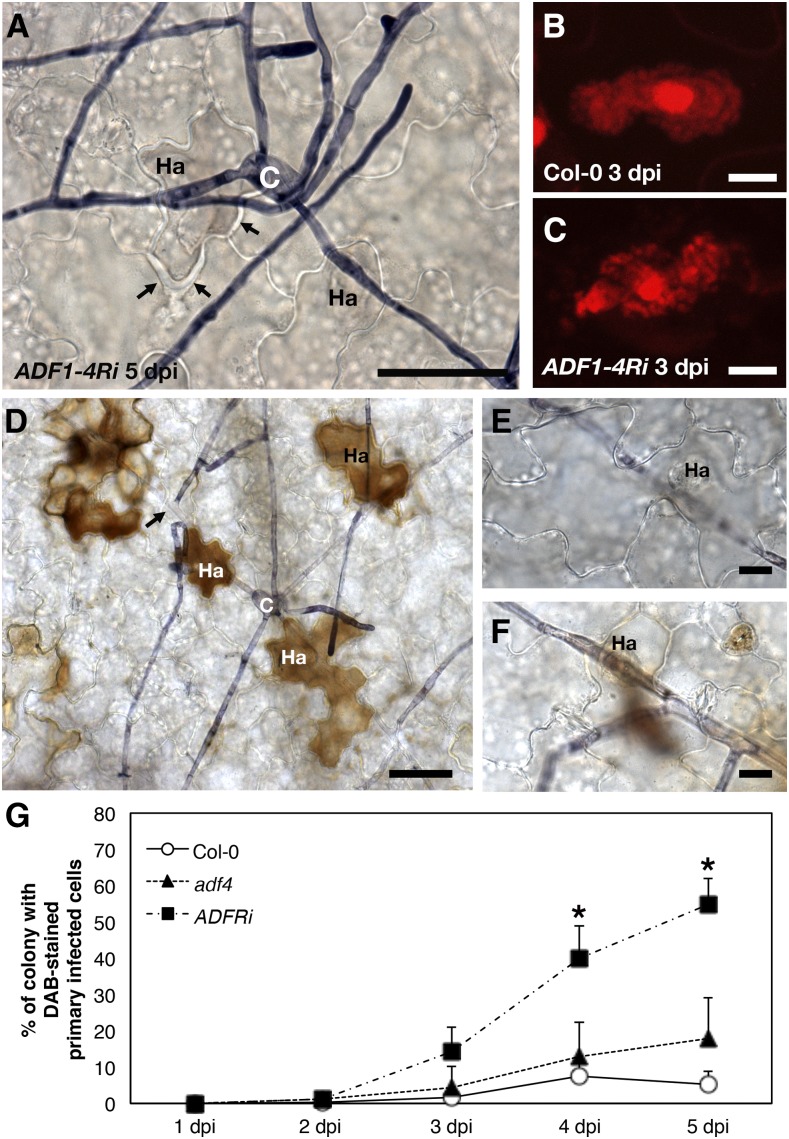

Figure 2.

G. orontii infected-cell-specific accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and cell death in ADF1-4Ri. A, Trypan Blue-stained ADF1-4Ri leaves at 5 dpi with G. orontii. C, Conidium; Ha, haustorium. Arrows indicate thickening of the cell wall. Bar = 50 µm. B and C, Maximum intensity projections of serial confocal sections of PI-stained G. orontii haustoria in Col-0 (B) and ADF1-4Ri (C) at 3 dpi. Bars = 10 µm. D to F, DAB- and Trypan Blue-stained ADF1-4Ri leaves at 5 dpi. Haustorium-containing cells located near the tip of the hypha indicated by the arrow in D are shown in E (containing developing young haustorium) and F (containing mature haustorium). Bars = 50 µm in D and 10 µm in E and F. G, Percentage of the colony with DAB-stained primary infected cells in Col-0 (white circles), adf4 (black triangles), and ADF1-4Ri (black squares). Error bars indicate sd (n = 5 biological replicates). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences when compared with the value of Col-0 (Student’s t test, *, P < 0.05).

At 5 dpi, infected leaves were treated with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB), which forms a brown precipitate in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (Thordal-Christensen et al., 1997). A strong brown precipitate was observed in infected cells of ADF1-4Ri located near conidia (Fig. 2D). Uninfected neighboring epidermal and mesophyll cells rarely showed DAB precipitation. Precipitation of DAB occurred most strongly in infected cells near conidia and less frequently in infected cells located near the hyphal tip (Fig. 2E). Powdery mildew hyphae continuously produce haustoria as the hypha grows; thus, infected cells near the hyphal tip contain young haustoria, whereas those near conidia contain well-developed or mature haustoria. Precipitation of DAB was more frequently observed with increasing proximity of infected cells to the conidium (Fig. 2F), which indicated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulated within infected cells of ADF1-4Ri as the haustoria mature and senesce.

The accumulation of ROS in infected cells was quantified by counting the percentage of colonies with DAB-stained primary infected cells from 1 to 5 dpi (Fig. 2G). The increase in ROS accumulation in infected cells of ADF1-4Ri leaves became significant at 4 dpi, while adf4 did not show a significant increase in ROS accumulation compared with the wild type in the experimental time frame.

Taken together, these results indicate that cell death induced in ADF1-4Ri-infected cells inhibited haustorial formation and, thus, fungal growth.

Powdery Mildew Resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri Was Suppressed by Mutations in SA and Jasmonic Acid Signaling But Not Ethylene Signaling

The phytohormones SA, jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) regulate signaling pathways involved in plant defense. In particular, SA signaling is the major pathway that mediates resistance against biotrophic pathogens such as powdery mildew fungi, whereas JA and ET, which often function antagonistically with SA, mediate responses against necrotrophic pathogens (Pieterse et al., 2012). To examine the role of those phytohormones in the powdery mildew resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri, we crossed adf4 and ADF1-4Ri plants with eds16 and pad4-1, which are mutants defective in SA production and signaling (Reuber et al., 1998; Wildermuth et al., 2001), with jar1-1, a mutant defective in JA signaling (Staswick et al., 2002), and with ein2-1, an ET signaling mutant (Alonso et al., 1999). Despite several attempts, we were unable to obtain adf4;ein2-1 homozygous plants. Therefore for ein2-1, only ADF1-4Ri;ein2-1 was tested for powdery mildew susceptibility. When G. orontii-inoculated plants were examined visually at 2 wpi (Fig. 3A), adf4 and ADF1-4Ri crossed with eds16 and pad4-1 showed mycelial formation comparable with that of Col-0 (adf4;pad4-1 and ADF1-4Ri;pad4-1 are not shown in Fig. 3A, but the phenotype was similar to that of adf4;eds16 and ADF1-4Ri;eds16). To our surprise, adf4 and ADF1-4Ri crossed with jar1-1 exhibited a recovery of susceptibility against G. orontii. ADF1-4Ri;ein2-1 retained increased resistance against G. orontii.

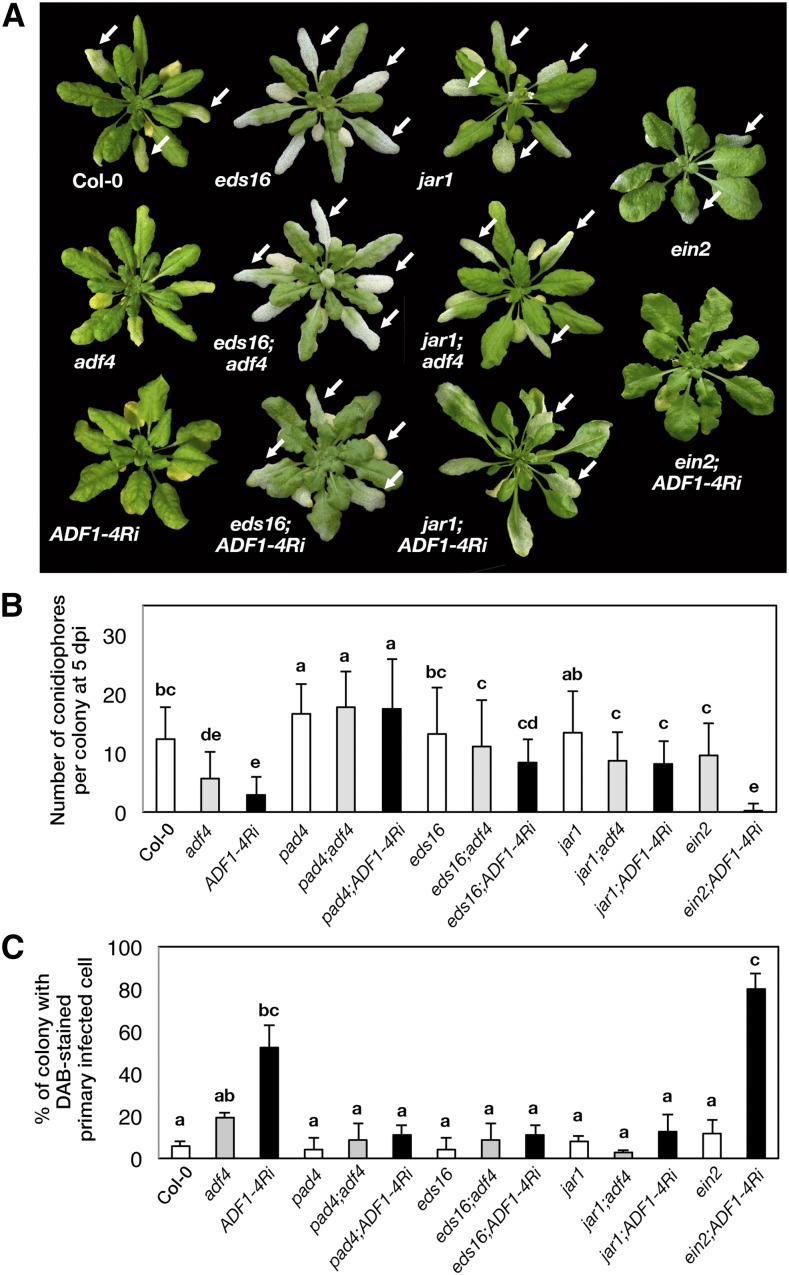

Figure 3.

Mutations with defects in SA and JA signaling suppressed the increased resistance to G. orontii in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri. A, Plants at 2 wpi with G. orontii. Leaves with powdery mildew mycelia are indicated by arrows. B, Number of conidiophores per colony counted at 5 dpi. The experiment was performed three times with similar results; results from one representative experiment are shown. Error bars indicate sd (n = 100). C, Percentage of the colony with DAB-stained primary infected cells at 5 dpi. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3 biological replicates). Comparisons between multiple groups were performed by ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. The same letter indicates that there are no significant differences (P < 0.05).

The introduction of eds16 or pad4-1 did not modify the leaf-shape phenotype of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri (Fig. 3A; adf4;pad4-1 and ADF1-4i;pad4-1 showed a similar leaf shape to that of adf4;eds16 and ADF1-4Ri;eds16). In contrast, the introduction of jar1-1 and ein2-1 severely altered the leaf shape of ADF1-4Ri; leaves of jar1-1:ADF1-4Ri plants were narrowed, and the border between the lamina and petiole was less distinct compared with that of the wild type. The rosette leaf of ein2-1 was flatter and more rounded compared with that of Col-0 under the growth conditions used, and the flatter leaf phenotype of ADF1-4Ri was further enhanced by the introduction of ein2-1 (Fig. 3A).

Susceptibility to G. orontii in these mutants was evaluated by counting the number of conidiophores per colony at 5 dpi (Fig. 3B) and the percentage of colonies with ROS accumulation in primary infected cells (Fig. 3C). The introduction of pad4-1, eds16, and jar1-1 increased the number of conidiophores compared with those of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri to a level similar to wild-type Col-0. The pad4-1, eds16, and jar1-1 mutations strongly inhibited the accumulation of ROS in G. orontii-infected cells of ADF1-4Ri leaves (Fig. 3C). Introduction of ein2-1 did not alter the G. orontii resistance phenotype of ADF1-4Ri (Fig. 3, B and C).

To further examine the role of phytohormone-mediated signaling in powdery mildew resistance in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri, we performed a quantitative analysis of mRNA accumulation of SA and JA markers. Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR analyses using PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE1 (PR1) as a marker for SA signaling revealed that ADF1-4Ri accumulated significantly higher quantities of PR1 mRNA in uninfected leaves (1,240-fold higher) and in infected 3-dpi leaves (22,400-fold higher; Fig. 4A). In contrast to Col-0 and adf4, in which PR1 mRNA accumulation continued to increase over the course of the experimental time frame, the PR1 expression level in ADF1-4Ri-infected leaves peaked at 3 dpi and then declined at 5 dpi. In contrast, the PR1 expression level was not altered significantly in adf4 compared with Col-0 in the experimental time frame. It is hypothesized that the accumulation of PR1 mRNA at 3 dpi in ADF1-4Ri reflects the promotion of SA-mediated resistance in infected cells, which results in ROS accumulation and cell death in infected cells at subsequent time points. We also examined the expression levels of PLANT DEFENSIN1.2 (PDF1.2) and VEGETATIVE STORAGE PROTEIN2 (VSP2), which are markers for the JA signaling pathway (Spoel et al., 2003). No significant difference in the expression levels of PDF1.2 and VSP2 was observed in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri compared with those of Col-0 throughout the experimental time frame (Fig. 4, B and C).

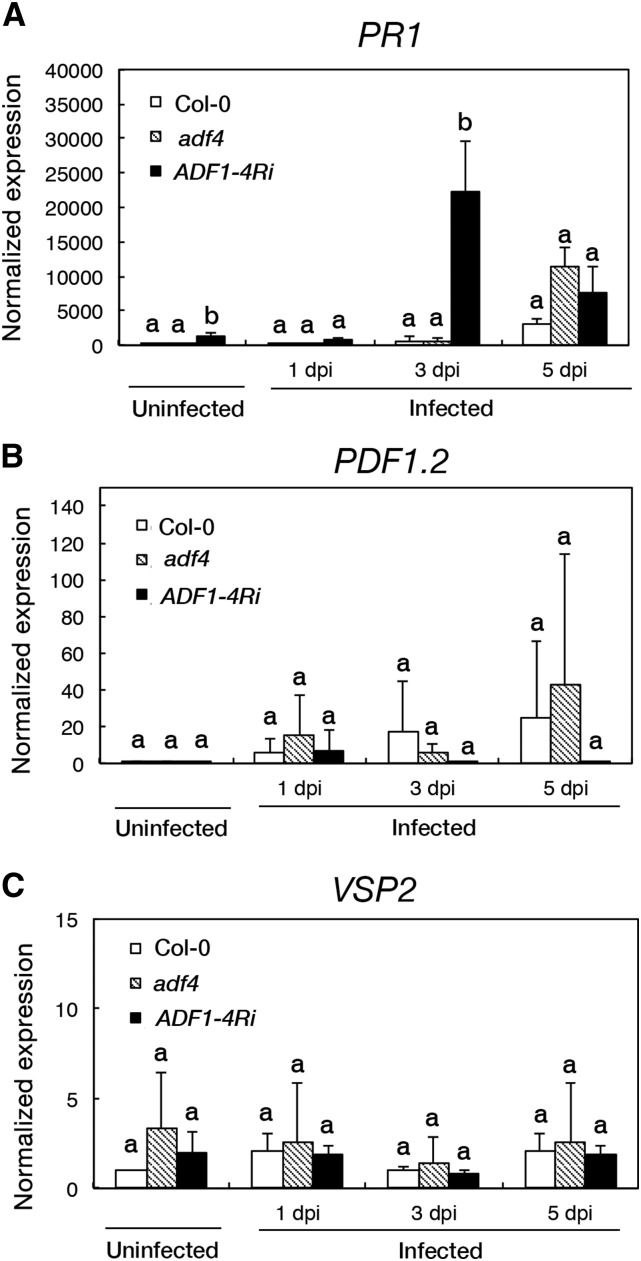

Figure 4.

Relative transcription levels of the SA marker PR1 and the JA markers PDF1.2 and VSP2 in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri plants inoculated with G. orontii. Transcription levels were determined by qRT-PCR. A, PR1. B, PDF1.2. C, VSP2. Values were normalized to the actin (ACT8) expression level. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3 biological replicates). Comparisons between multiple groups (Col-0, adf4, and ADF1-4Ri) were performed by ANOVA for each time point. The same letter indicates that there are no significant differences (P < 0.05).

AF Organization Was Affected Only at Very Early Infection Time Point in ADF1-4Ri

The major function of ADF is the regulation of AF organization and dynamics. Although the role of AFs in plant resistance against nonhost powdery mildew fungi is well established (Takemoto and Hardham, 2004), the role of AFs in the interaction between the host plant and an adapted fungal pathogen is less clear. To examine if AFs function in the plant-adapted powdery mildew fungus interaction, we inoculated fiz1, a dominant mutant of ACT8 that shows strongly disrupted AF organization (Kato et al., 2010), with G. orontii. We observed that both fiz1 homozygous and heterozygous plants showed increased resistance against G. orontii (Supplemental Fig. S4). This result clearly indicated that AFs play a role in the interaction with an adapted powdery mildew fungus.

Several Arabidopsis lines have been generated for the visualization of AF organization: the GFP-tagged mouse Talin (GFP-mTalin; Kost et al., 1998), GFP-hTalin (Takemoto et al., 2003), GFP-ABD2 (Higaki et al., 2007), and Lifeact-Venus (Era et al., 2009). We compared these plants to select an optimal line with which to analyze the AF organization of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri and explore the role of AFs in the plant-powdery mildew interaction. When epidermal cells of mature rosette leaves were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy, GFP-ABD2 showed a highly chimeric expression pattern in which most of epidermal cells lacked fluorescence (Supplemental Fig. S5A). GFP-hTalin showed the highest intensity and most stable fluorescence throughout the mature epidermal cells (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Although both GFP-mTalin and Lifeact-Venus showed stable expression (Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D), the fluorescence intensity of these lines was much lower compared with GFP-hTalin. Due to its loss of fluorescence in mature leaf epidermal cells, the GFP-ABD2 line was not included for further analyses.

GFP-mTalin was shown previously to inhibit the actin-depolymerizing activity of ADF in vitro (Ketelaar et al., 2004). The actin-binding domain of hTalin showed 99% identity of amino acid sequence with mTalin (Supplemental Fig. S6), and the GFP-hTalin line showed similar AF organization to GFP-mTalin (Supplemental Fig. S7). However, neither GFP-hTalin nor GFP-mTalin showed a suppressive effect on G. orontii proliferation (Supplemental Fig. S8). Lifeact-Venus also showed a degree of susceptibility to G. orontii comparable to that of Col-0.

The introduction of GFP-hTalin did not alter the adf4 and ADF1-4Ri phenotypes of increased resistance to G. orontii and flattening of mature rosette leaves (Supplemental Fig. S9), whereas the introduction of Lifeact-Venus to adf4 produced severely dwarfed plants (Supplemental Fig. S10). adf4 expressing GFP-hTalin also retained a phenotype of elongated hypocotyls when grown in the dark (Henty et al., 2011; Supplemental Fig. S11A). Although an increase in the level of AF bundling and a decrease of AF density in adf4 hypocotyl epidermal cells, which were reported previously in an experiment using the GFP-ABD2 line (Henty et al., 2011), were not observed in our experiment (Supplemental Fig. S11, B and C), an increase in the level of bundling in epidermal cells located near the root was detected in the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S11B). Together with its high and stable expression in epidermal cells of mature rosette leaves, we chose GFP-hTalin to study the organization of AFs in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri plants.

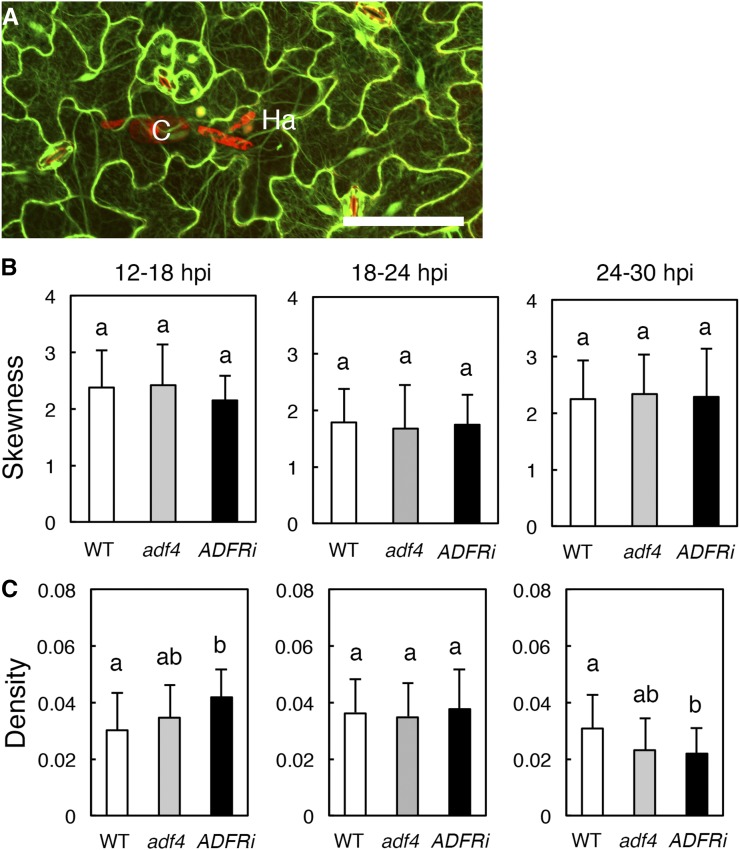

We performed microscopic image analysis for the quantitative evaluation of AF bundling and density (Higaki et al., 2010b) in both uninfected (Supplemental Fig. S12) and G. orontii-infected (Fig. 5) cells of GFP-hTalin, GFP-hTalin/adf4, and GFP-hTalin/ADF1-4Ri. There were no significant differences in AF organization in uninfected adf4 and ADF1-4Ri (Supplemental Fig. S12) and in the metrics of AF bundling in infected adf4 and ADF1-4Ri (Fig. 5B) compared with the wild type. On the other hand, AF density in ADF1-4Ri was increased significantly at an early time point (12–18 hpi, just after the invasion of G. orontii; Fig. 5C). At a later time point (24–30 hpi), on the other hand, AF density in ADF1-4Ri was significantly more decreased compared with the wild type or adf4. After 24 hpi, we found that the fluorescence intensity of GFP-hTalin in primary infected cells started to decrease significantly (Supplemental Fig. S13). This reduction of GFP-hTalin fluorescence is not the result of cell death but of a decrease in the expression of GFP-hTalin, because an enhancement of brightness revealed that filamentous AFs still remained in those cells (Supplemental Fig. S13A).

Figure 5.

The density of AFs was increased significantly in ADF1-4Ri, but not in adf4, at early infection time points. A, Maximum intensity projection of serial confocal sections of Arabidopsis epidermal cells infected by G. orontii. AFs were visualized by GFP-hTalin, and G. orontii was visualized by staining with PI. C, Conidium; Ha, haustorium. Bar = 50 µm. B and C, Quantitative analyses of AF bundling (B) and density (C) in G. orontii-infected cells at 12 to 18, 18 to 24, and 24 to 30 hpi. Error bars indicate sd (n = 17–37 cells and n = 3–5 rosette leaves from three to five plants). The skewness of the GFP-hTalin fluorescence intensity distribution (B) and GFP-hTalin signal occupancy (C) were used as indicators of AF bundling and density, respectively (Higaki et al., 2010b). Comparisons between multiple groups (wild type [WT], adf4, and ADF1-4Ri) were performed by ANOVA for each data set. The same letter indicates that there are no significant differences (P < 0.05).

We further tested the effect on AF organization caused by the loss of ADF expression by examining the resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri against the nonadapted powdery mildew fungus Bgh. The strong remodeling of AFs at attempted invasion sites is crucial for resistance against Bgh, and disruption of AFs by treatment with an inhibitor results in the increased invasion of a nonadapted powdery mildew fungus (Takemoto and Hardham, 2004). Neither adf4 nor ADF1-4Ri showed a significant increase in penetration resistance against nonadapted Bgh (Supplemental Fig. S14). Actin microfilaments regulate the movement of organelles, such as mitochondria (Henty-Ridilla et al., 2013). GFP-labeled mitochondria showed dynamic movement in ADF1-4Ri at a speed comparable with that of the wild type (Supplemental Movies S1 and S2). Actin dynamics were also examined by a quantitative analysis of the effect of latrunculin B (LatB) treatment on AFs. LatB inhibits actin polymerization; thus, LatB treatment causes a shortening of AFs when actin turnover takes place (Gibbon et al., 1999). In ADF1-4Ri, but not in adf4, AFs were more resistant against LatB treatment compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S15).

Taken together, Arabidopsis subclass I ADFs do have functions in the regulation of AF dynamics; however, the adf4 single mutant does not exhibit significant alterations in the organization and dynamics of AFs in mature leaf epidermal cells, which was unexpected considering its significant increase in resistance against G. orontii.

Nuclear Localization and Phosphorylation of ADF4 Are Both Important for Powdery Mildew Susceptibility

To further investigate the function of ADFs, we conducted complementation analysis with ADF4 fused to GFP. In previous studies that examined the intracellular localization of plant ADFs, GFP was fused at either the N terminus (Dong et al., 2001, 2013; Tian et al., 2009; Porter et al., 2012) or the C terminus (Daher et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2012) of ADF. The majority of previous reports utilized the ADF coding sequence driven by the 35S promoter, except for a report by Daher et al. (2011), in which the genomic region of ADF7 and ADF10, including the 1-kb promoter region, coding region with introns, and 3′ untranslated region (UTR), was used to analyze the intracellular localization of ADF7 and ADF10 during the development of the male gametophyte. Cyan fluorescent protein or yellow fluorescent protein was inserted at the C terminus of ADF in this study. As overexpression of ADF could interfere with plant development (Dong et al., 2001) and response to the powdery mildew fungus (Miklis et al., 2007), we cloned the ADF4 genomic region containing the 1.5-kb ADF4 promoter, introns, and 3′ UTR for examination of the subcellular localization and function of ADF in the Arabidopsis-G. orontii interaction. The ADF4 genomic construct fused with GFP inserted upstream of the first exon (GFP-ADF4) was transformed into adf4, and T2 plants were examined. GFP-ADF4 showed both dotted and diffuse cytosolic localization (Supplemental Fig. S16A). Although G. orontii haustorium is surrounded by host AFs (Inada et al., 2016), no filamentous structure was observed around the haustorium (Supplemental Fig. S16B). Fluorescence dots were also observed in the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S16C). This localization pattern was unexpected, as previous studies reported that ADF4 localized along AFs and throughout the nucleus (Ruzicka et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2009; Daher et al., 2011; Porter et al., 2012). Although T2 plants with GFP fluorescence showed a recovery of powdery mildew susceptibility, in T3 adf4 homozygous plants, the fluorescence intensity was very weak, particularly in mature leaves, and showed little complementation in any of the four isolated lines tested.

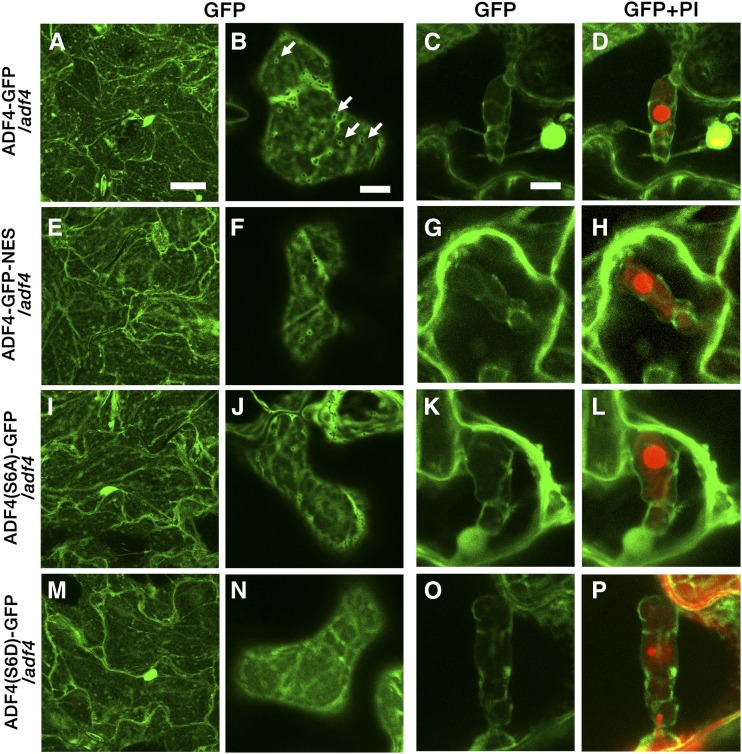

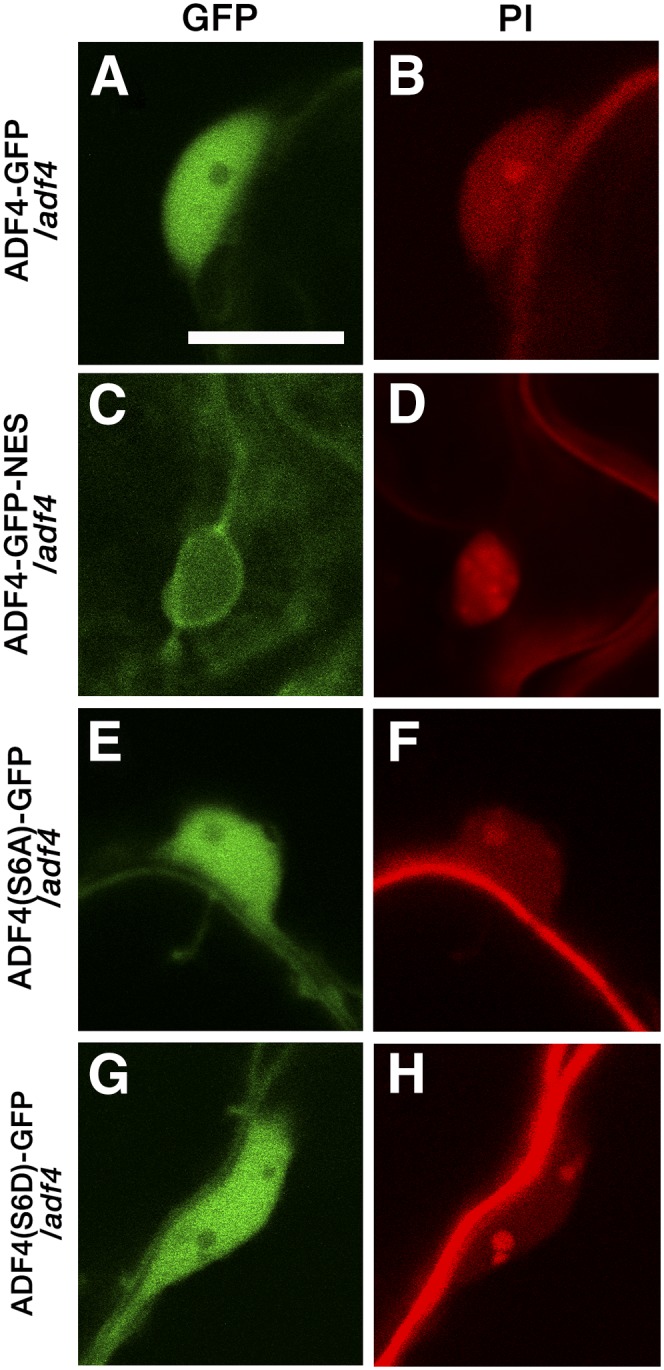

In contrast, the ADF4 genomic region fused with GFP inserted at the C terminus of ADF4 (ADF4-GFP) showed both filamentous and cytosolic fluorescence patterns (Figs. 6, A–D). Strong fluorescence signal was seen around organelles (Fig. 6B), which could be plastids, as previous immunostaining observation using anti-ADF antibody found a strong accumulation of ADF4 around chloroplasts (Ruzicka et al., 2007). The partial colocalization of ADF4-FP with AFs was confirmed by the observation of ADF4-red fluorescent protein (RFP) transformed into GFP-hTalin/adf4 (Supplemental Fig. S17). The fluorescent signal of ADF4-GFP was observed throughout the nucleus but was excluded from the nucleolus (Fig. 7, A and B). Three isolated T4 homozygous lines showed fluorescence intensity in epidermal cells of mature rosette leaves that is sufficiently high for detailed observation and full suppression of the enhanced powdery mildew resistance of adf4 (Supplemental Fig. S18, A–C). Interestingly, the flattened leaf shape in adf4 was not fully suppressed in the transgenic lines (Supplemental Fig. S18C), whereas the elongation of the etiolated hypocotyl of adf4 (Henty et al., 2011) was suppressed by the expression of ADF4-GFP (Supplemental Fig. S19). The number of conidiophores in ADF4-GFP plants at 5 dpi was comparable with that of Col-0 (Fig. 8), further confirming the full complementation of adf4 powdery mildew fungal resistance in ADF4-GFP.

Figure 6.

Intracellular localization of ADF4-GFP, ADF4-GFP-NES, ADF4(S6A)-GFP, and ADF4(S6D)-GFP. ADF4-GFP (A–D), ADF4-GFP-NES (E–H), ADF4(S6A)-GFP (I–L), and ADF4(S6D)-GFP (M–P) are shown in mature leaf epidermal cells (A, B, E, F, I, J, M, and N) and around PI-stained haustoria (C, D, G, H, K, L, O, and P). Arrows in B indicate fluorescence around organelles. Bars = 20 µm (A, E, I, and M) and 10 µm (B–D, F–H, J–L, and N–P).

Figure 7.

Nuclear localization of ADF4-GFP, ADF4-GFP-NES, ADF4(S6A)-GFP, and ADF4(S6D)-GFP. Nuclei and cell walls of Arabidopsis transgenic lines were stained with PI. Bar = 10 µm.

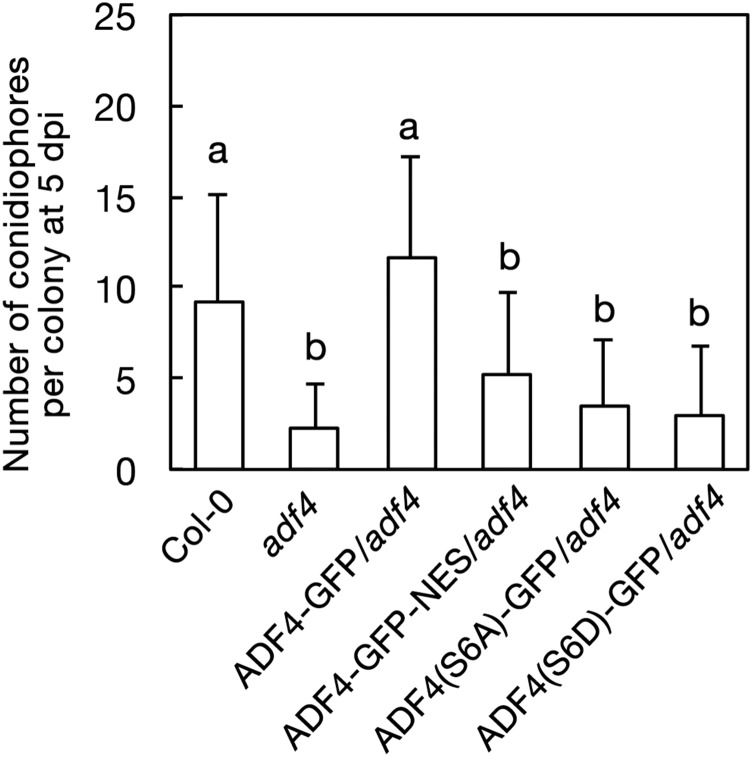

Figure 8.

Powdery mildew susceptibility in transgenic lines. The number of conidiophores per colony was counted at 5 dpi. Three independent experiments were performed and showed similar results; the results of one representative experiment are shown. Error bars indicate sd (n = 50 colonies). Comparisons between multiple groups (Col-0, adf4, and transgenic lines) were performed by ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. The same letter indicates that there are no significant differences (P < 0.05).

In addition to the regulation of AFs in the cytoplasm, ADF is suggested to function in the nucleus as a chaperone of actin monomers (Jiang et al., 1997; Bernstein and Bamburg, 2010). Actin monomers regulate gene expression and chromatin remodeling (Zheng et al., 2009). To test if the localization of ADF4 in the nucleus is important for susceptibility to G. orontii, we first analyzed changes in an accumulation of ADF4-GFP in the nucleus upon G. orontii infection (Supplemental Fig. S20). We found no significant difference in the level of ADF4-GFP accumulation in the nucleus between infected cells and uninfected cells. Then we cloned ADF4-GFP fused with a nuclear exporting signal (NES) and transformed the construct into adf4. ADF4-GFP-NES showed a filamentous fluorescence pattern at the cell surface (Fig. 6, E and F) and around haustoria (Fig. 6, G–H) in a similar manner to ADF4-GFP. The fluorescent signal in the nucleus was markedly reduced in ADF4-GFP-NES (Fig. 7, C and D; Supplemental Fig. S21). The increased resistance to G. orontii was retained in ADF4-GFP-NES, as shown by limited mycelial formation on the leaves at 2 wpi (Supplemental Fig. S18D), and the number of conidiophores was comparable with those of adf4 (Fig. 8). This result strongly indicates that the nuclear localization of ADF4 is crucial in susceptibility to G. orontii.

The function of ADFs is regulated by the phosphorylation of Ser at the N terminus. The phosphorylation of ADFs inhibits their capability to bind to actin monomers and filaments (Mizuno, 2013). The phosphomimetic isoform of ADF4 (ADF4_S6D) complemented the enhanced susceptibility of adf4 to Pst DC3000 AvrPhpB, whereas the phospho-null isoform of ADF4 (ADF4_S6A) did not (Porter et al., 2012). We constructed phospho-null (ADF4_S6A) and phosphomimetic (ADF4_S6D) isoforms of ADF4 based on the genomic ADF4-GFP construct [ADF4(S6A)-GFP and ADF4(S6D)-GFP, respectively]. Both ADF4(S6A)-GFP and ADF4(S6D)-GFP showed intracellular and nuclear localization similar to that of ADF4-GFP [Figs. 6, I–L, and 7, E and F, for ADF4(S6A)-GFP and Figs. 6, M–P, and 7, G and H, for ADF4(S6D)-GFP]. Surprisingly, both mutants did not suppress the increased resistance to G. orontii of adf4 (Fig. 8; Supplemental Fig. S18). Although the role of the phosphorylation of ADF4 in plant-pathogen interaction is unknown, this result indicates that the mode of action of ADF4 in resistance against Pst AvrPhpB differs from that in the susceptibility to G. orontii.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the loss of Arabidopsis ADF4 and the knockdown of four members of subclass I ADFs, namely ADF1 to ADF4, prominently enhance resistance against the adapted powdery mildew fungus G. orontii. The adf4 mutant and ADF1-4Ri did not show the formation of microlesions or dwarfism, which are observed in many previously reported mutants with enhanced powdery mildew resistance. The increased powdery mildew resistance in ADF1-4Ri was accompanied by the disruption of haustoria, increased accumulation of ROS, and death of infected cells. Although the accumulation of ROS and cell death were not significant in adf4, the increased resistance in both adf4 and ADF1-4Ri was suppressed by the introduction of mutations in SA- or JA-related pathways. Thus, we consider that the phenotype of ADF1-4Ri is an enhanced adf4 phenotype.

It was surprising that both SA- and JA-related mutations suppressed the enhanced resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri, as most previously reported Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced powdery mildew resistance show a dependence on SA signaling but not on JA signaling. The only exception is cev1, which was identified in a screen of plants with constitutive activation of the JA pathway (Ellis and Turner, 2001). Although both SA-related pad4-1 and eds16 and JA-related jar1-1 notably suppressed powdery mildew resistance in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that only the SA pathway was correspondingly up-regulated in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri. Kim et al. (2014) recently proposed that JA and PAD4 have compensatory functions in the activation of the SA pathway at later time points of P. syringae infection. Based on our results that a single mutation of JA (jar1-1) showed only a partial complementation of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri, we speculate that the JA-signaling pathway functions in the activation of SA signaling in the resistance against G. orontii of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri.

In this study, we chose an Arabidopsis line expressing GFP-hTalin for detailed analysis of AF organization after comparison with three other widely used actin-visualizing Arabidopsis lines, GFP-ABD2, GFP-mTalin, and Lifeact-Venus. Although those lines had been surveyed previously and compared for effects on plant development and AF organization (Dyachok et al., 2014) and the GFP-ABD2 line is generally considered an optimal line that reflects an intact AF organization (Higaki et al., 2010a; Dyachok et al., 2014), the investigation was limited to seedlings. We found a loss of GFP-ABD2 fluorescence in most mature leaf epidermal cells. Labuz et al. (2010) also reported that the expression level of GFP-ABD2 decreases as the plant matures, even though the construct is driven by the 35S promoter. Lifeact-Venus had been used for the observation of AF dynamics in Arabidopsis and liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha; Era et al., 2009). Although the expression of Lifeact-Venus itself does not affect wild-type plant development (van der Honing et al., 2011), the development of adf4 was dramatically hindered. Those results indicate that an optimal actin-visualizing line is different depending on developmental stages or mutants of interest.

By using the GFP-hTalin line, however, we failed to detect changes in AF organization in etiolated adf4 hypocotyl epidermal cells, which were detected in an experiment using the GFP-ABD2 line (Henty et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that an increased level of AF bundling in GFP-hTalin (Higaki et al., 2010a; Dyachok et al., 2014; Supplemental Fig. S8) had masked the changes in the AF organization in adf4. However, the fact that we detected an increase in AF bundling in hypocotyl epidermal cells near the root and an increase in AF density in ADF1-4Ri at an early G. orontii infection time point using GFP-hTalin indicates that this line could detect changes in AF organization. Considering the higher degree of suppression of G. orontii proliferation even in the adf4 single mutant compared with the actin mutant fiz1 (compare the mycelial coverage of leaves at 2 wpi in adf4 presented in Fig. 1A with that in fiz1 in Supplemental Fig. S4), the absence of significant changes in the organization of AFs in adf4, which were shown not only by quantitative analysis of GFP-hTalin images but also by nonadapted powdery mildew fungus infection analysis (Supplemental Fig. S14) and quantitative analysis of the LatB effect on AF organization (Supplemental Fig. S15), was still unexpected. It is possible that an effect of ADF4 loss on AF organization would appear at a later infection time point, such as 2 or 3 dpi, which could not be analyzed because of the loss of fluorescence of GFP-hTalin in primary infected cells. This reduction in fluorescence could be the result of an increase in plant immunity, which accompanies an increased activity of RNA silencing (Katiyar-Agarwal and Jin, 2010) and, thus, a reduction in transgene expression. As this timing of fluorescence reduction in primary infected cells was correlated with the timing of fungus secondary hyphal formation, we speculate that fungus partitions more energy to form a second haustorium and less energy in a suppression of plant immunity in primary infected cells, resulting in an increase of plant immunity in primary infected cells. In this regard, a significant reduction of AF density found in ADF1-4Ri at 24 to 30 hpi (Fig. 5C) could be the result of an increased plant immunity and RNA-silencing activity in ADF1-4Ri.

An absence of significant changes in AF organization in adf4 may indicate that the function of subclass I ADF in G. orontii susceptibility is separated from its function in the regulation of AF organization and dynamics. To test this possibility, we examined if ADF4-GFP-NES could complement the elongated-hypocotyl phenotype. It was shown previously that the adf1 knockout mutant also shows an elongation of etiolated hypocotyl, which was not complemented by the expression of ADF1 with mutations in the actin-binding domains (Dong et al., 2013). As shown in Supplemental Fig. S22, the elongated hypocotyl phenotype in adf4 was partially rescued by the expression of ADF4-GFP-NES, supporting the hypothesis that the function of ADF in the regulation of AF organization and that in G. orontii susceptibility is separated.

Besides the regulation of AF organization and dynamics, a function in gene expression regulation and chromatin modification has been proposed as a role of ADF4 (Porter and Day, 2013). Our data demonstrating the importance of the nuclear localization of ADF4 and the up-regulation of PR1 in ADF1-4Ri even in absence of pathogen are in agreement with this hypothesis. As discussed previously, this ADF function in gene regulation could be mediated by its possible role in the nuclear transport of monomeric actin, which possesses a nuclear exporting signal and functions in the regulation of gene expression and chromatin structure (Bernstein and Bamburg, 2010).

Infected-cell-specific death has been observed in the wild type attacked by adapted powdery mildew fungus (Höwing et al., 2014). The increased frequency of infected-cell-specific death and increased amplitude of PR1 induction in ADF1-4Ri appear to suggest the increased basal defense level and primed defense response in ADF1-4Ri and, possibly, in adf4. However, a general increase in basal defense in adf4 is unlikely, since the susceptibility against Pst DC3000 is not altered (Tian et al., 2009). Together with the facts that ADF mutants exhibit both increased susceptibility and increased resistance depending on the pathogens (see introduction) and that the mode of action by which ADF4 confers resistance against Pst DC3000 AvrPphB and susceptibility to G. orontii is different (this study), we propose that ADF4 functions in a direct interaction with G. orontii, possibly with pathogenic effector(s).

Many bacterial and oomycete effectors are targeted to the host nucleus and function in the regulation of host gene expression (Schornack et al., 2010; Caillaud et al., 2012; Canonne and Rivas, 2012). Although some phytobacterial effectors show a nuclear localization signal (NLS), others lack an obvious NLS; thus, the mechanism by which the effector is transported to the host nucleus is unknown (Rivas, 2012). It is tempting to speculate that effectors lacking an NLS interact directly with ADFs for transport to the host nucleus, where the effectors function in the suppression of defense-related gene expression. Recently, G. orontii effector candidates (OECs) were analyzed for their interaction with host Arabidopsis proteins. Yeast two-hybrid screening revealed that 23 OECs interact with the Arabidopsis transcription factor TCP14, and among them, 15 were localized in the nucleus (Weßling et al., 2014). Our original search found that only four out of 15 OECs that localized in the nucleus are predicted to have an NLS when analyzed with NLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi; Kosugi et al., 2009). Although ADF4 was not identified as an interactor with OECs by Weßling et al. (2014), the OECs used in their analysis were identified from a complementary DNA (cDNA) library generated from isolated haustoria and chosen for their possession of canonical secretion peptides (Weßling et al., 2012, 2014). In contrast, the Bgh effectors AVRa10 and AVRk1 do not have canonical secretion peptides, although their functionality in the host cytoplasm has been demonstrated (Ridout et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2007). In addition, AVRk1 has not been identified in 6,000 ESTs generated from isolated Bgh haustoria (Godfrey et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that there is an unidentified G. orontii effector(s) that interacts with ADF4 and functions in the infection. As the first step to test this possibility of ADF4 function in a direct interaction with pathogenic effector(s), it is of interest to test the susceptibility of adf4 against other Arabidopsis-adapted powdery mildew fungi, such as Erysiphe cruciferarum, Golovinomyces cichoracearum, and Oidium neolycopersici (Micali et al., 2008).

In summary, we identified Arabidopsis subclass I ADF as a susceptibility factor for G. orontii. Further analysis of ADF4 function could contribute to the understanding of the mechanism of plant immunity against and that of interaction with G. orontii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds were suspended in autoclaved 0.1% agarose and incubated at 4°C for vernalization for more than 1 d (up to 2 weeks) before direct sowing on 1:1 metromix:vermiculite in plastic pots. Entire pots were covered with plastic wrap for 1 week after sowing to maintain humidity and to encourage germination. For powdery mildew (Golovinomyces orontii) infection experiments, plants were grown at 22°C in a growth chamber (Biotron LPH-350SP; NK Systems) under a 12-h-light/12-h-dark photoperiod. Four-week-old plants that had not produced inflorescence stems were used for powdery mildew fungus infection. To investigate the timing of when plants start to produce an inflorescence, plants were grown at 22°C in a growth chamber under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod. For investigation of the F1 population of Lifeact-Venus/adf4, seeds were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol and plated on 1× Murashige and Skoog medium containing 0.8% agar. Seeds were incubated at 4°C for at least 2 d and then grown at 22°C with continuous light. Seedlings were observed using a stereomicroscope (MZ10F; Leica Microsystems) equipped with light-emitting diode illumination, an ET GFP2 filter (Leica), and a CCD camera (DP73; Olympus). For measurement of hypocotyl length, surface-sterilized seeds were plated on 1× Murashige and Skoog medium with 1.5% agar, stratified, and then grown in the dark at 22°C until measurement.

Powdery Mildew Infection

The Arabidopsis-adapted powdery mildew fungus G. orontii MGH and barley (Hordeum vulgare)-adapted Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei race 1 were maintained on mature pad4 rosette leaves and on wild-type barley ‘Kobinkatagi’ leaves, respectively, under the same conditions as used for Arabidopsis growth. Heavily sporulating pad4 leaves at 2 wpi or barley leaves at 1 wpi were used for infection using a previously described settling tower method (Plotnikova et al., 1998).

Trypan Blue Staining of Powdery Mildew

For the observation of powdery mildew fungal morphology, Trypan Blue staining of fixed leaves was performed as described previously (Inada and Savory, 2011). Briefly, leaves were detached and submerged in 99% ethanol at each time point and incubated until they were decolorized completely. Fixed leaves were stained with 250 μg mL−1 Trypan Blue in 1:1:1 (v/v) lactic acid:glycerol:water solution for approximately 15 min at room temperature and destained in the same solution without Trypan Blue. Stained leaves were mounted in 70% glycerol and observed using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope equipped with ×10 numerical aperture (N.A.) 0.3, ×20 N.A. 0.5, and ×40 N.A. 0.95 objectives (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). Images were obtained using a cooled AxioCam MRc CCD camera controlled by AxioVision.

DAB Staining

G. orontii-infected leaves at each time point were incubated in 1% (w/v) DAB aqueous solution (pH 3.8) for 8 h in the light, then transferred to 70% ethanol and finally 100% ethanol before staining with Trypan Blue as described above. Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera (Carl Zeiss).

Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy

For haustorial observation, a 2-mm-diameter disc was cut from infected leaves using a cork borer and incubated in 0.5% PI (Sigma) containing 2.5% mannitol and 0.01% Silwet, according to the previously described protocol (Koh et al., 2005). Images of haustoria were captured with an Olympus confocal scanning laser microscope equipped with a ×20 N.A. 0.8 objective lens (FV1000; Olympus). Images were processed using ImageJ software version 1.48v (National Institutes of Health). For observation of the AF structures and ADF4 localization, an Olympus FV1000 confocal system was used. Observation at low magnification (entire cells) was performed using a ×20 N.A. 0.8 objective, whereas observation at high magnification (haustoria and nucleus) was undertaken using a ×60 N.A. 1.2 water-immersion objective (Olympus). GFP was excited with a 488-nm argon laser, and the emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 500- to 530-nm bandpass filter. Venus was excited with a 515-nm argon laser, and the emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 530- to 630-nm bandpass filter. PI was excited with a 488-nm argon laser, and the emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 555- to 655-nm bandpass filter. The brightness of the obtained images was enhanced with Adobe Photoshop (CS6) for clear presentation.

Image Analysis

To quantify AF bundling and density, the metric parameters skewness of fluorescence intensity distributions and fluorescence signal occupancy were used (Higaki et al., 2010b; http://hasezawa.ib.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp/zp/Kbi/HigStomata/). Target epidermal cell regions were segmented based on PI signal from the cell wall with ImageJ software. The skeletonized AF pixels were extracted from the serial confocal sections using the ImageJ software plugin KbiLineExtract (Ueda et al., 2010). To evaluate the degree of AF disruption by LatB treatment, we measured the occupancy of 22- × 22-μm square regions (35 × 35 pixels) from epidermal cell regions in the maximum intensity projection images.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Powdery mildew-infected and uninfected leaves were harvested and frozen in liquid N2 at 7 dpi. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using a 20-nucleotide oligo(dT) primer and ReverTra Ace reverse transcriptase (Toyobo). A one-tenth concentration of cDNA was used for qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master and the LightCycler system (Roche Diagnostics). Expression levels were normalized to that of ACT8. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Intracellular Localization of ADF4

To produce GFP-ADF4, primers specific for the 1.5-kb ADF4 promoter region, cDNA of GFP with a linker at the C terminus, and ADF4 genomic region including exons, introns, and the 3′ flanking region were used. The combined three fragments were amplified, and the resultant 3.6-kb fragment was cloned into the D-TOPO pENTR vector (Life Technologies). To produce ADF4-GFP, primers specific for the 2.5-kb fragment including the ADF4 promoter, exons and introns, and cDNA of GFP with a linker at the N terminus were used. The combined two fragments were amplified, and the resultant 3.3-kb fragment was cloned into the D-TOPO pENTR vector, which was then digested with AscI and ligated to the 3′ UTR of ADF4, which was amplified using ADF4 3′ UTR-specific primers. For the cloning of ADF4-RFP, primers specific to tagRFP (Merzlyak et al., 2007) were amplified, and the resulting fragment was inserted in the place of GFP of the ADF4-GFP plasmid. For the cloning of ADF4-GFP-NES, primers specific for a 2.9-kb ADF4 genomic region including the 1.5-kb promoter, exons, introns, GFP fused with a nuclear exporting signal, and the ADF4 3′ UTR region were used. The combined three fragments were amplified and cloned into the D-TOPO pENTR vector. ADF4(S6A)-GFP and ADF4(S6D)-GFP were constructed based on ADF4-GFP in the D-TOPO pENTR plasmid using specific primers. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The clones in pENTR were transferred to the binary vector pGWB1 (Nakagawa et al., 2007), and the resulting plasmids were used for transformation.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Increased resistance against the adapted powdery mildew fungus G. orontii in four independent transgenic lines (ADF1-4Ri).

Supplemental Figure S2. G. orontii penetration rate.

Supplemental Figure S3. Flowering time in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri.

Supplemental Figure S4. Increased resistance against G. orontii in the dominant-negative actin mutant fiz1.

Supplemental Figure S5. Maximum intensity projections of serial confocal sections of epidermal cells of plants expressing GFP-ABD2, GFP-hTalin, GFP-mTalin, and Lifeact-Venus.

Supplemental Figure S6. Comparison of the amino acid sequences between hTalin and mTalin actin-binding domains.

Supplemental Figure S7. Quantitative evaluation of AF bundling and density in GFP-hTalin and GFP-mTalin.

Supplemental Figure S8. Powdery mildew susceptibility in actin microfilament visualization lines.

Supplemental Figure S9. Introduction of GFP-hTalin does not alter the increased powdery mildew resistance of adf4 and ADF1-4Ri.

Supplemental Figure S10. Introduction of Lifeact-Venus into adf4 produces dwarf plants.

Supplemental Figure S11. The organization of AFs labeled with GFP-hTalin in the epidermal cells of elongated hypocotyls was not changed significantly in adf4.

Supplemental Figure S12. No significant alteration was seen in the organization of AFs in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri uninfected cells.

Supplemental Figure S13. The fluorescence intensity of GFP-hTalin was reduced significantly in G. orontii infected cells at 2 dpi.

Supplemental Figure S14. Resistance against the nonadapted powdery mildew fungus Bgh in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri.

Supplemental Figure S15. Increased resistance of AFs against LatB treatment in adf4 and ADF1-4Ri.

Supplemental Figure S16. Intracellular localization of GFP-ADF4.

Supplemental Figure S17. Colocalization of GFP-hTalin and ADF4-RFP.

Supplemental Figure S18. Powdery mildew susceptibility in three independent lines of ADF4-GFP/adf4: ADF4-GFP-NES/adf4, ADF4(S6A)-GFP/adf4, and ADF4(S6D)-GFP/adf4.

Supplemental Figure S19. ADF4-GFP suppresses hypocotyl elongation in adf4.

Supplemental Figure S20. The amount of ADF4 in the nucleus does not change upon powdery mildew fungus infection.

Supplemental Figure S21. GFP is excluded from the nucleus in adf4 expressing ADF4-GFP-NES.

Supplemental Figure S22. Hypocotyl length in adf4 expressing ADF4-GFP-NES.

Supplemental Table S1. Gene-specific primers for qRT-PCR and plasmid construction used in this study.

Supplemental Movie S1. Dynamic movement of GFP-labeled mitochondria in wild-type epidermal cells.

Supplemental Movie S2. Dynamic movement of GFP-labeled mitochondria in ADF1-4Ri epidermal cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Shitomi Nakagawa, Dr. Nanaho Fukuda, Prof. Yusuke Saijo, and Dr. Kei Hiruma at NAIST for experimental assistance; Profs. Masao Tasaka, the late Ko Shimamoto, Takashi Hashimoto and members of his laboratory, members of the Plant Global Education Project at NAIST, and Prof. Chris Staiger at Purdue University for valuable discussions; Prof. Brad Day at Michigan State University for the generous gift of the adf4 mutant, adf4 expressing the ADF4 genomic sequence, and ADF1-4Ri lines; Prof. Yoshitaka Takano at Kyoto University for providing the ein2-1 mutant; Prof. Masao Tasaka at NAIST for Arabidopsis lines expressing GFP-mTalin or mtGFP; Prof. Adrienne Hardham at the Australian National University for providing the GFP-hTalin line; and Prof. Takashi Ueda at the University of Tokyo for the Lifeact-Venus line.

Glossary

- SA

salicylic acid

- AF

actin microfilament

- Bgh

Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei

- Pst

Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato

- wpi

weeks post inoculation

- Col-0

Columbia-0

- dpi

days post inoculation

- PI

propidium iodide

- DAB

3,3-diaminobenzidine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- JA

jasmonic acid

- ET

ethylene

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

- LatB

latrunculin B

- UTR

untranslated region

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- OECs

G. orontii effector candidates

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- N.A.

numerical aperture

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Scientific Research for Plant Graduate Student from NAIST, supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology to N.I., and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant no. 25711017 for T.H. and grant nos. 24114007 and 25291056 for S.H.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR (1999) EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284: 2148–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR (2010) ADF/cofilin: a functional node in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol 20: 187–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Rivera B, Ruzicka DR, Deal RB, McKinney EC, King-Reid L, Meagher RB (2008) ACTIN DEPOLYMERIZING FACTOR9 controls development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 68: 619–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud MC, Piquerez SJ, Fabro G, Steinbrenner J, Ishaque N, Beynon J, Jones JD (2012) Subcellular localization of the Hpa RxLR effector repertoire identifies a tonoplast-associated protein HaRxL17 that confers enhanced plant susceptibility. Plant J 69: 252–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canonne J, Rivas S (2012) Bacterial effectors target the plant cell nucleus to subvert host transcription. Plant Signal Behav 7: 217–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran D, Inada N, Hather G, Kleindt CK, Wildermuth MC (2010) Laser microdissection of Arabidopsis cells at the powdery mildew infection site reveals site-specific processes and regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 460–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran D, Rickert J, Huang Y, Steinwand MA, Marr SK, Wildermuth MC (2014) Atypical E2F transcriptional repressor DEL1 acts at the intersection of plant growth and immunity by controlling the hormone salicylic acid. Cell Host Microbe 15: 506–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran D, Tai YC, Hather G, Dewdney J, Denoux C, Burgess DG, Ausubel FM, Speed TP, Wildermuth MC (2009) Temporal global expression data reveal known and novel salicylate-impacted processes and regulators mediating powdery mildew growth and reproduction on Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 149: 1435–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clément M, Ketelaar T, Rodiuc N, Banora MY, Smertenko A, Engler G, Abad P, Hussey PJ, de Almeida Engler J (2009) Actin-depolymerizing factor2-mediated actin dynamics are essential for root-knot nematode infection of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 2963–2979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consonni C, Humphry ME, Hartmann HA, Livaja M, Durner J, Westphal L, Vogel J, Lipka V, Kemmerling B, Schulze-Lefert P, et al. (2006) Conserved requirement for a plant host cell protein in powdery mildew pathogenesis. Nat Genet 38: 716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher FB, van Oostende C, Geitmann A (2011) Spatial and temporal expression of actin depolymerizing factors ADF7 and ADF10 during male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 1177–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day B, Henty JL, Porter KJ, Staiger CJ (2011) The pathogen-actin connection: a platform for defense signaling in plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 49: 483–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CH, Tang WP, Liu JY (2013) Arabidopsis AtADF1 is functionally affected by mutations on actin binding sites. J Integr Plant Biol 55: 250–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CH, Xia GX, Hong Y, Ramachandran S, Kost B, Chua NH (2001) ADF proteins are involved in the control of flowering and regulate F-actin organization, cell expansion, and organ growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 1333–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyachok J, Sparks JA, Liao F, Wang YS, Blancaflor EB (2014) Fluorescent protein-based reporters of the actin cytoskeleton in living plant cells: fluorophore variant, actin binding domain, and promoter considerations. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 71: 311–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Karafyllidis I, Wasternack C, Turner JG (2002) The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 links cell wall signaling to jasmonate and ethylene responses. Plant Cell 14: 1557–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Turner JG (2001) The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 has constitutively active jasmonate and ethylene signal pathways and enhanced resistance to pathogens. Plant Cell 13: 1025–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Era A, Tominaga M, Ebine K, Awai C, Saito C, Ishizaki K, Yamato KT, Kohchi T, Nakano A, Ueda T (2009) Application of Lifeact reveals F-actin dynamics in Arabidopsis thaliana and the liverwort, Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1041–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Innes RW (1998) An Arabidopsis mutant with enhanced resistance to powdery mildew. Plant Cell 10: 947–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Tang D, Innes RW (2001) Negative regulation of defense responses in plants by a conserved MAPKK kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 373–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Duan X, Tang C, Li X, Voegele RT, Wang X, Wei G, Kang Z (2014) TaADF7, an actin-depolymerizing factor, contributes to wheat resistance against Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Plant J 78: 16–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ (1999) Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell 11: 2349–2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey D, Böhlenius H, Pedersen C, Zhang Z, Emmersen J, Thordal-Christensen H (2010) Powdery mildew fungal effector candidates share N-terminal Y/F/WxC-motif. BMC Genomics 11: 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo CY, Wu GH, Xing J, Li WQ, Tang DZ, Cui BM (2013) A mutation in a coproporphyrinogen III oxidase gene confers growth inhibition, enhanced powdery mildew resistance and powdery mildew-induced cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep 32: 687–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henty JL, Bledsoe SW, Khurana P, Meagher RB, Day B, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ (2011) Arabidopsis actin depolymerizing factor4 modulates the stochastic dynamic behavior of actin filaments in the cortical array of epidermal cells. Plant Cell 23: 3711–3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henty-Ridilla JL, Li J, Day B, Staiger CJ (2014) ACTIN DEPOLYMERIZING FACTOR4 regulates actin dynamics during innate immune signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 340–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henty-Ridilla JL, Shimono M, Li J, Chang JH, Day B, Staiger CJ (2013) The plant actin cytoskeleton responds to signals from microbe-associated molecular patterns. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki T, Kojo KH, Hasezawa S (2010a) Critical role of actin bundling in plant cell morphogenesis. Plant Signal Behav 5: 484–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki T, Kurusu T, Hasezawa S, Kuchitsu K (2011) Dynamic intracellular reorganization of cytoskeletons and the vacuole in defense responses and hypersensitive cell death in plants. J Plant Res 124: 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki T, Kutsuna N, Sano T, Kondo N, Hasezawa S (2010b) Quantification and cluster analysis of actin cytoskeletal structures in plant cells: role of actin bundling in stomatal movement during diurnal cycles in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J 61: 156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki T, Sano T, Hasezawa S (2007) Actin microfilament dynamics and actin side-binding proteins in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10: 549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höwing T, Huesmann C, Hoefle C, Nagel MK, Isono E, Hückelhoven R, Gietl C (2014) Endoplasmic reticulum KDEL-tailed cysteine endopeptidase 1 of Arabidopsis (AtCEP1) is involved in pathogen defense. Front Plant Sci 5: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada N, Higaki T, Hasezawa S (2016) Quantitative analyses on dynamic changes in the organization of host Arabidopsis thaliana actin microfilaments surrounding the infection organ of the powdery mildew fungus Golovinomyces orontii. J Plant Res 129: 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada N, Savory EA (2011) Inhibition of prepenetration processes of the powdery mildew Golovinomyces orontii on host inflorescence stems is reduced in the Arabidopsis cuticular mutant cer3 but not in cer1. J Gen Plant Pathol 77: 273–281 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang CJ, Weeds AG, Hussey PJ (1997) The maize actin-depolymerizing factor, ZmADF3, redistributes to the growing tip of elongating root hairs and can be induced to translocate into the nucleus with actin. Plant J 12: 1035–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar-Agarwal S, Jin H (2010) Role of small RNAs in host-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol 48: 225–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Morita MT, Tasaka M (2010) Defects in dynamics and functions of actin filament in Arabidopsis caused by the dominant-negative actin fiz1-induced fragmentation of actin filament. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsiarimpa A, Kalinowska K, Anzenberger F, Weis C, Ostertag M, Tsutsumi C, Schwechheimer C, Brunner F, Hückelhoven R, Isono E (2013) The deubiquitinating enzyme AMSH1 and the ESCRT-III subunit VPS2.1 are required for autophagic degradation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 2236–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler SA, Shimosato-Asano H, Keinath NF, Wuest SE, Ingram G, Panstruga R, Grossniklaus U (2010) Conserved molecular components for pollen tube reception and fungal invasion. Science 330: 968–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, Anthony RG, Hussey PJ (2004) Green fluorescent protein-mTalin causes defects in actin organization and cell expansion in Arabidopsis and inhibits actin depolymerizing factor’s actin depolymerizing activity in vitro. Plant Physiol 136: 3990–3998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Tsuda K, Igarashi D, Hillmer RA, Sakakibara H, Myers CL, Katagiri F (2014) Mechanisms underlying robustness and tunability in a plant immune signaling network. Cell Host Microbe 15: 84–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S, André A, Edwards H, Ehrhardt D, Somerville S (2005) Arabidopsis thaliana subcellular responses to compatible Erysiphe cichoracearum infections. Plant J 44: 516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost B, Spielhofer P, Chua NH (1998) A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J 16: 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H (2009) Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10171–10176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labuz J, Krzeszowiec W, Gabrys H (2010) Threshold change in expression of GFP-FABD2 fusion protein during development of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Acta Biol Cracov Ser Bot 52: 103–107 [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Wu G, Xu X, Luan H, Zhi H, Cui J, Cui X, Chen X (2015) Soybean actin-depolymerizing factor 2 interacts with soybean mosaic virus-encoded P3 protein. Virus Genes 50: 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciver SK, Hussey PJ (2002) The ADF/cofilin family: actin-remodeling proteins. Genome Biol 3: reviews3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzlyak EM, Goedhart J, Shcherbo D, Bulina ME, Shcheglov AS, Fradkov AF, Gaintzeva A, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov S, Gadella TW, et al. (2007) Bright monomeric red fluorescent protein with an extended fluorescence lifetime. Nat Methods 4: 555–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micali C, Gollner K, Humphry M, Consonni C, Panstruga R (2008) The powdery mildew disease of Arabidopsis: a paradigm for the interaction between plants and biotrophic fungi. The Arabidopsis Book 6: e0115, doi/10.1199/tab.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklis M, Consonni C, Bhat RA, Lipka V, Schulze-Lefert P, Panstruga R (2007) Barley MLO modulates actin-dependent and actin-independent antifungal defense pathways at the cell periphery. Plant Physiol 144: 1132–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K. (2013) Signaling mechanisms and functional roles of cofilin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Cell Signal 25: 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kurose T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, Niwa Y, Toyooka K, Matsuoka K, Jinbo T, Kimura T (2007) Development of series of Gateway Binary Vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J Biosci Bioeng 104: 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura MT, Stein M, Hou BH, Vogel JP, Edwards H, Somerville SC (2003) Loss of a callose synthase results in salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance. Science 301: 969–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CM, Van der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC (2012) Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28: 489–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikova JM, Reuber TL, Ausubel FM (1998) Powdery mildew pathogenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mycologia 90: 1009–1016 [Google Scholar]

- Porter K, Day B (2013) Actin branches out to link pathogen perception and host gene regulation. Plant Signal Behav 8: e23468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K, Shimono M, Tian M, Day B (2012) Arabidopsis Actin-Depolymerizing Factor-4 links pathogen perception, defense activation and transcription to cytoskeletal dynamics. PLoS Pathog 8: e1003006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuber TL, Plotnikova JM, Dewdney J, Rogers EE, Wood W, Ausubel FM (1998) Correlation of defense gene induction defects with powdery mildew susceptibility in Arabidopsis enhanced disease susceptibility mutants. Plant J 16: 473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout CJ, Skamnioti P, Porritt O, Sacristan S, Jones JD, Brown JK (2006) Multiple avirulence paralogues in cereal powdery mildew fungi may contribute to parasite fitness and defeat of plant resistance. Plant Cell 18: 2402–2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas S. (2012) Nuclear dynamics during plant innate immunity. Plant Physiol 158: 87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzicka DR, Kandasamy MK, McKinney EC, Burgos-Rivera B, Meagher RB (2007) The ancient subclasses of Arabidopsis actin depolymerizing factor genes exhibit novel and differential expression. Plant J 52: 460–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schornack S, van Damme M, Bozkurt TO, Cano LM, Smoker M, Thines M, Gaulin E, Kamoun S, Huitema E (2010) Ancient class of translocated oomycete effectors targets the host nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17421–17426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen QH, Saijo Y, Mauch S, Biskup C, Bieri S, Keller B, Seki H, Ulker B, Somssich IE, Schulze-Lefert P (2007) Nuclear activity of MLA immune receptors links isolate-specific and basal disease-resistance responses. Science 315: 1098–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel SH, Koornneef A, Claessens SM, Korzelius JP, Van Pelt JA, Mueller MJ, Buchala AJ, Métraux JP, Brown R, Kazan K, et al. (2003) NPR1 modulates cross-talk between salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent defense pathways through a novel function in the cytosol. Plant Cell 15: 760–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE, Tiryaki I, Rowe ML (2002) Jasmonate response locus JAR1 and several related Arabidopsis genes encode enzymes of the firefly luciferase superfamily that show activity on jasmonic, salicylic, and indole-3-acetic acids in an assay for adenylation. Plant Cell 14: 1405–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu S. (2004) Phylogeny and evolution of the powdery mildew fungi (Erysiphales, Ascomycota) inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycoscience 45: 147–157 [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto D, Hardham AR (2004) The cytoskeleton as a regulator and target of biotic interactions in plants. Plant Physiol 136: 3864–3876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto D, Jones DA, Hardham AR (2003) GFP-tagging of cell components reveals the dynamics of subcellular re-organization in response to infection of Arabidopsis by oomycete pathogens. Plant J 33: 775–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Ade J, Frye CA, Innes RW (2005a) Regulation of plant defense responses in Arabidopsis by EDR2, a PH and START domain-containing protein. Plant J 44: 245–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Ade J, Frye CA, Innes RW (2006) A mutation in the GTP hydrolysis site of Arabidopsis dynamin-related protein 1E confers enhanced cell death in response to powdery mildew infection. Plant J 47: 75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Christiansen KM, Innes RW (2005b) Regulation of plant disease resistance, stress responses, cell death, and ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis by the EDR1 protein kinase. Plant Physiol 138: 1018–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang ZG, Wei YD, Collinge DB (1997) Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants: H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J 11: 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Chaudhry F, Ruzicka DR, Meagher RB, Staiger CJ, Day B (2009) Arabidopsis actin-depolymerizing factor AtADF4 mediates defense signal transduction triggered by the Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPphB. Plant Physiol 150: 815–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H, Yokota E, Kutsuna N, Shimada T, Tamura K, Shimmen T, Hasezawa S, Dolja VV, Hara-Nishimura I (2010) Myosin-dependent endoplasmic reticulum motility and F-actin organization in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 6894–6899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Honing HS, van Bezouwen LS, Emons AMC, Ketelaar T (2011) High expression of Lifeact in Arabidopsis thaliana reduces dynamic reorganization of actin filaments but does not affect plant development. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 68: 578–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]