Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the sensitivity and clinical utility of intraoperative mobile gamma camera (MGC) imaging in sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in melanoma.

Background

The false-negative rate for SLNB for melanoma is approximately 17%, for which failure to identify the sentinel lymph node (SLN) is a major cause. Intraoperative imaging may aid in detection of SLN near the primary site, in ambiguous locations, and after excision of each SLN. The present pilot study reports outcomes with a prototype MGC designed for rapid intraoperative image acquisition. We hypothesized that intraoperative use of the MGC would be feasible and that sensitivity would be at least 90%.

Methods

From April to September 2008, 20 patients underwent Tc99 sulfur colloid lymphoscintigraphy, and SLNB was performed with use of a conventional fixed gamma camera (FGC), and gamma probe followed by intraoperative MGC imaging. Sensitivity was calculated for each detection method. Intraoperative logistical challenges were scored. Cases in which MGC provided clinical benefit were recorded.

Results

Sensitivity for detecting SLN basins was 97% for the FGC and 90% for the MGC. A total of 46 SLN were identified: 32 (70%) were identified as distinct hot spots by preoperative FGC imaging, 31 (67%) by preoperative MGC imaging, and 43 (93%) by MGC imaging pre- or intraoperatively. The gamma probe identified 44 (96%) independent of MGC imaging. The MGC provided defined clinical benefit as an addition to standard practice in 5 (25%) of 20 patients. Mean score for MGC logistic feasibility was 2 on a scale of 1–9 (1 = best).

Conclusions

Intraoperative MGC imaging provides additional information when standard techniques fail or are ambiguous. Sensitivity is 90% and can be increased. This pilot study has identified ways to improve the usefulness of an MGC for intraoperative imaging, which holds promise for reducing false negatives of SLNB for melanoma.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has become standard practice in management and staging of melanoma. Despite its routine role in clinical management of melanoma, it has a higher false-negative rate than is generally recognized.1–4 A recent review from 8 series in 7829 patients reports a weighted mean false-negative rate of 16.6%.1 This has significant negative implications for the management and outcomes of melanoma. An assessment of the causes of false-negative results reported that 44% of false negatives were due to failure of radiologic or surgical identification of the sentinel lymph node.2 Thus, to optimize lymph node staging and regional control of melanoma, new approaches to improve the technical approach to lymphatic mapping and SLNB are needed.

Currently, lymphatic mapping depends on preoperative fixed gamma camera (FGC) imaging performed outside of the operating suite. It has been estimated in SLNB for breast cancer that the mean detection rate of FGC imaging is 70% to 98%.5–8 If FGC imaging is ambiguous, or if information during the surgical case calls into question the preoperative findings, there is no mechanism for the surgeon to reimage the patient in the operating room. In addition, there is no routine postoperative imaging obtained to confirm removal of all SLNs at the end of the procedure.

To improve localization of sentinel nodes with unusual or ambiguous location, a few centers have explored the use of combined single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and x-ray computed tomography (CT) imaging in adjunct with or in place of traditional planar lymphoscintigraphy to provide 3-dimensional localization and to improve correlation between hot spots and anatomical landmarks.9–13 Improvement has been reported in SLNB node detection sensitivity using SPECT/CT, with greater benefit in complex lymphatic drainage areas such as the head and neck or trunk.9,12 Furthermore, addition of SPECT/CT imaging has been reported to alter the surgical approach in 35% of patients with inconclusive conventional lymphoscintograms.9 However, SPECT/CT exposes patients to much greater doses of ionizing radiation than lymphoscintigraphy alone,14,15 which may increase future cancer risks.14 In addition, SPECT/CT adds significant cost9 and, most importantly, does not address the need for intraoperative imaging of the patient during SLNB.

Intraoperative imaging with mobile gamma cameras (MGCs) has been investigated in pilot studies for SLNB in Europe and Asia5,16–19 and in other clinical settings besides SLNB20,21; however, these studies did not evaluate MGC use in SLNB for melanoma. Although the results of these studies suggest that intraoperative MGC imaging is feasible and decreases the length of the surgical procedure,18 MGCs have not yet been incorporated into routine clinical care in this country.

The majority of the MGCs tested intraoperatively to date have used high-resolution parallel hole collimators. In the pilot study described here, an MGC equipped with a higher sensitivity parallel hole collimator (15 cps/µCi) was evaluated at a single institution with the goal of obtaining images with reasonable counting statistics in a short period. The higher sensitivity collimator was intended to speed acquisition in the operating room, trading off some degree of spatial resolution. The purpose of the study was to determine the value of real-time, intraoperative MGC imaging in terms of node detection sensitivity and operating room logistics in the context of SLNB in melanoma patients.

METHODS

Participants

Between April and September 2008, inclusive, we enrolled 20 consecutive participants with a diagnosis of malignant melanoma meeting the criteria for SLNB, who gave informed consent. The institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained (IRB #13565).

MGC Device Specifications

The mobile gamma camera used in this study was provided on loan from The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (Jefferson Lab) in Newport News, Va. The MGC head is held by an adjustable gantry arm mounted on a mobile cabinet. The arm is counterbalanced to permit easy arm height adjustment. The mobile cabinet contains a personal computer for detector control and image processing and display and readout electronics. The MGC comprises a 5 × 5 array of 1-in2 Hamamatsu C8-series position-sensitive photomultiplier tubes (PSPMTs) tiled together for an overall field of view of 13 cm × 13 cm. The C8 PSPMTs utilize an 8 × 8 crossed-wire anode readout. In this camera, adjacent wire anode pairs are connected together. As a result, there are a total of 40 electronic readout channels, 20 in each dimension. The PSPMT array is optically coupled to a hermetically sealed NaI(Tl) crystal matrix. The crystal assembly contains a 40 × 40 array of 3 mm × 3 mm × 6-mm-thick crystals, separated by a 0.3-mm layer of light reflecting aluminum oxide powder (3.3-mm crystal pitch) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Sample MGC Imaging sequence in a participant with a left upper extremity melanoma that drained to the left axilla. All images were obtained over 60 seconds. A, Anterior MGC image of the participant’s left axilla before incision for SLNB. B, Ex vivo image of SLN#1. C, Anterior image of left axilla after removal of SLN 1.

The readout is capable of data acquisition rates of up to 100 kHz without suffering significant dead time losses. Image acquisition, processing, and display are implemented in the detector control software, written in Kmax 8.2.2 (Sparrow Corp, Port Orange, Fla). The JAVA-based Kmax environment permits integration of high-level image processing and analyses tools such as ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md).

Before the start of this pilot study, an assessment of the MGC sensitivity was performed outside the operating suite using SLNs that had been removed and were in formalin for delivery to the pathologists. It was apparent then that the sensitivity of the MGC as originally configured was too low for intraoperative use, resulting in data acquisition times that would not be acceptable in the operative room. In response to this finding, a new reconfigured parallel hole collimator was fabricated that was designed to increase sensitivity about 6-fold. The resulting camera efficiency for 140 keV 99mTc gamma rays was 4.0 × 10−4 (15 cps/µCi). Subsequent evaluation with SLNs revealed that the higher sensitivity collimator permits images to be acquired within 30 to 120 seconds, while permitting identification of individual nodes, and also has adequate spatial resolution to allow 2 or more nodes within the same image field to be distinguished from each other.

Lymphoscintigraphy

All participants underwent routine lymphoscintigraphy in the nuclear medicine suite on the day before or the day of surgery. For all cases, approximately 0.5 mCi of filtered Tc-99m sulfur colloid (Cardinal Health, Inc, Dublin, Ohio) was injected intradermally, in 4 to 8 injections and circumferentially around the primary lesion or the scar from biopsy of the primary lesion. Immediately after injection, the participant was placed under the FGC (ADAC Forte, Phillips Electronics, Andover, Mass) and static images were taken to identify hot spots and a handheld point source was used to outline the patient. The skin overlying the hot spot was marked with indelible ink to guide intraoperative identification.

SLN Detection With the MGC and Handheld Gamma Probe

The participants were imaged with the MGC before incision for the SLNB in all 20 cases (Fig. 2). MGC images were also taken of the surgical bed after removal of each SLN and of the SLN ex vivo (Fig. 2). During surgery, a handheld, nonimaging gamma probe (C-Trak, Care Wise Medical Products Corp, Morgan Hill, Calif) was used to guide identification of the SLNs in accordance with routine clinical practice (SLNs were defined as the hottest lymph node and all nodes with probe counting rates ≥10% of that of the hottest SLN). Detection of hot spots by the FGC, MGC, and probe was recorded. Toxicity was recorded and feasibility was assessed on a 9-point scale. In addition, the investigator was asked to record specific cases in which the MGC was particularly useful as an adjunct to standard clinical practice. The same surgical team (L.T.D. and C.L.S.) operated on all the participants. In accordance with our standard clinical practice,22 we did not use isosulfan blue in this series.

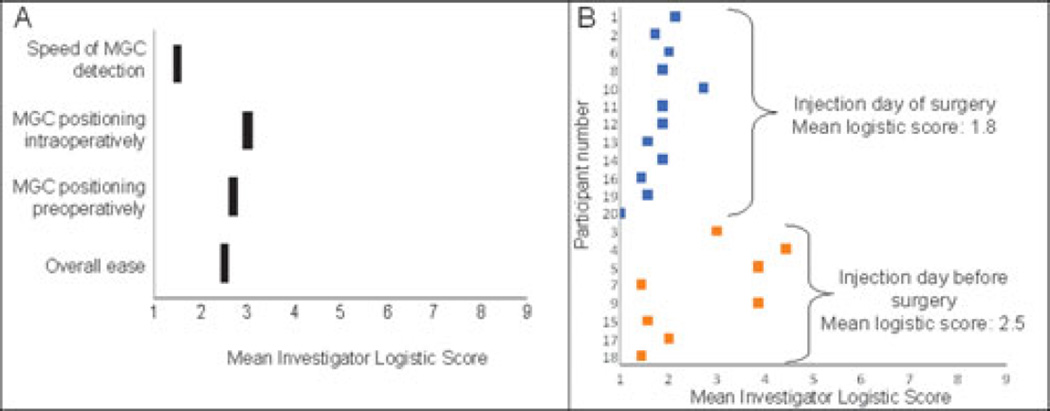

FIGURE 2.

A, Average scoring by investigator for 20 study participants of logistical challenges for use of MGC imaging in pilot study. Logistics were graded on a scale of 1 to 9, with 1 being “outstanding” and 9 being “prevented completion of the study.” B, Analysis of logistical challenges comparing participants injected with radio-labeled colloid the day before surgery versus participants injected the day of surgery demonstrates that logistical challenges were less for same-day participants, although this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.23).

Feasibility Assessment

A 5-question “logistic questionnaire” was developed to assess investigator opinion on the feasibility and usefulness of the MGC. Each of the 5 questions was answered on a scale of 1 to 9 by the same surgical team for each participant with a score of 1 denoting “outstanding” and a score of 9 denoting “prevented completion of the study.” The average over the 5 questions resulted in a participant-specific total score.

Statistics

For estimation of rates (sensitivity, false positive, etc), the unit of analysis is SLN and not participant. Basic summary measures such as frequencies, point estimates, and appropriate exact 90% confidence intervals were used to describe binary outcomes. A Mann-Whitney rank-sum test was used to compare differences in the means of feasibility and logistics evaluation.

RESULTS

Sentinel Lymph Node Identification in Pilot Study With Standard Methods

Twenty participants were enrolled in this pilot study, with primary melanomas located on the trunk (8), upper extremity (7), lower extremity (4), and head and neck (1). Standard surgical methods were employed to identify and to remove sentinel nodes, including preoperative lymphoscintigraphy with 99mTc-sulfur colloid and FGC imaging, plus intraoperative use of a handheld gamma probe. In the 20 participants, 46 SLNs were identified (mean 2.3 per patient), in 30 lymph node basins or atypical locations: axillary (13), inguinal (5), intransit (5), supraclavicular (2), pelvic (2), neck (2), and triangular intramuscular space (1) locations. Of the 46 SLNs identified, 44 SLNs were removed for histologic analysis. In each of 2 patients, 2 of 3 SLNs were removed, leaving a third SLN either in the pelvis or deep to chest wall musculature, to minimize patient morbidity.

Sensitivity of FGC and MGC for Identification of Node Basins Containing SLN

Of the 30 lymph node basins with SLNs, 29 were identified by preoperative FGC imaging after lymphoscintigraphy. One SCL basin was missed because it was obscured by shine-through from the injection site on the ipsilateral posterior shoulder. Of those 30 lymph node basins, 27 were identified by intraoperative MGC imaging. The three false negatives with the MGC were in 2 participants who underwent 99mTc-sulfur colloid injection and lymphoscintigraphy the day before surgery, resulting in a delay of more than 20 hours from injection to MGC imaging and relatively low radiotracer activity in the nodes. Thus, the sensitivity for detection of basins containing 1 or more SLNs was 97% (90% CI, 85%–100%) for the FGC and 90% (90% CI, 76%–97%) for the MGC. Twelve of the 20 participants were taken to the operating room the same day as the lymphoscintigraphy and had SLNs in 19 basins, of which all 19 (100%; 90% CI, 85%–100%) were detected with MGC.

Sensitivity of FGC and MGC for Identification of SLNs

Of the 46 SLNs, 32 were identified as distinct hot spots by preoperative FGC imaging after lymphoscintigraphy, and 31 were identified by preoperative MGC imaging (Table 1). In many cases, a single hot spot on preoperative imaging represented 2 or more SLNs in proximity to each other. However, because the MGC is available for use intraoperatively after the wide local excision and after excision of each SLN, 43 were identified by intraoperative MGC imaging. Thus, the overall sensitivity for detection of SLNs was 70% for the FGC and 93% for the MGC, a difference manifest by availability of the MGC intraoperatively. Of the 12 participants taken to the operating room the same day as the lymphoscintigraphy, all of the 29 SLNs (100%; 90% CI, 90%–100%) were detected with the MGC.

TABLE 1.

Detection of SLNs by Imaging With FGC and MGC Before SLNB Was Recorded as Preoperative Imaging

| Device | Detected SLNs (#) | Total SLNs (#) | Sensitivity (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGC | 32 | 46 | 70% (57%–81%) |

| MGC preoperatively | 31 | 46 | 67% (54%–79%) |

| MGC | 43 | 46 | 93% (84%–98%) |

| Probe | 44 | 46 | 96% (87%–99%) |

After removal of the first SLN in each lymph node basin, the basin was evaluated for additional SLNs with both the MGC and the handheld probe. The probe initially missed 2 SLNs, which were located with the MGC and then confirmed with the probe.

Sensitivity of Handheld Gamma Probe for Identification of SLNs

Intraoperative use of the handheld gamma probe ultimately detected all 46 SLN, but 2 of them were missed on initial assessment (Table 1). One was an intransit node on the left upper extremity very close to the injection site, which was equivocal in the radiologist’s evaluation of the FGC images, and it was not distinguishable from the injection site on initial evaluation with the probe. In that case, evaluation with the MGC quickly identified the location of that hot spot, which was confirmed by directed reevaluation with the handheld probe. In a second case, after removing 2 SLNs from the left neck (with total 10-second counts of 1837 and 963 when the excised nodes were placed directly on the probe’s collimator), the remaining bed count on evaluation with the handheld probe was less than 10% of the hottest node (92), but imaging with the MGC showed a missed SLN. With that information and guidance, that third SLN was then detected by the handheld probe (238 counts in 10 seconds) and was removed (ex vivo 10-second count of 392 = 21% of hottest node). Thus, the MGC imaging provided critical guidance for the handheld probe in 2 of 20 patients (10%), and permitted detection of 2 of the 46 SLNs that would likely have been missed without the MGC but were subsequently confirmed with standard techniques. Thus, the sensitivity of the handheld probe for detection of SLNs was 96% (44 of 46; 90% CI, 87%–99%).

Safety and Operator Opinion of Intraoperative Imaging With the MGC

There were no adverse events. Opinion of the feasibility and usefulness of the MGC was assessed with the logistic questionnaire immediately after each surgical case. Each question was scored on a 9-point scale, with 1 being best and 9 being worst. The mean score for overall ease of use was 2.5 (range, 1–5). Mean scores for the ease of MGC positioning preoperatively and intraoperatively were 2.7 (range, 1–5) and 3.0 (range, 1–7), respectively. The speed of MGC detection of nodes received a mean score of 1.5 (range, 1–4, Fig. 2A). The mean score for the value of the MGC imaging in identifying hot spots preoperatively and for identifying residual nodes was 2.8 (range, 1–8) and for confirming completion of the case was 2.4 (range, 1–7), respectively. There was a trend toward greater logistical challenges in participants injected with radio-labeled colloid the day before surgery as compared with those injected the day of surgery (as is commonly done for scheduling reasons), although this was not significant (Fig. 2B).

The MGC Was Clinically Useful as an Adjunct to Standard Practice in 25% of Patients

In addition to assessing the overall value of MGC imaging, our pilot study identified 6 specific clinical benefits in 5 patients where the MGC imaging had identifiable impact on surgical management (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Six Investigator-identified Scenarios in Which MGC Imaging Had Identifiable Impact on Surgical Management

| Participant No. | Clinical Advantage Provided by MGC Imaging |

|---|---|

| 3 | MGC imaging after wide local excision detected hot spots obscured by the injection site on preoperative MGC and FGC imaging |

| 3 | Detected a third SLN that was missed by the FGC and probe would not have been removed without the use of the MGC. |

| 12 | Intraoperative MGC imaging allowed the surgeon to manipulate the tissues and demonstrate that what initially appeared to bea single SLN represented 3 low-activity (nonsentinel) lymph nodes (Fig. 3). |

| 11 | Intraoperative MGC imaging allowed visualization after clearing of lymphatic pooling. What was seen as a hot spot on FGC was confirmed to be a false positive with the MGC. |

| 20 | Intraoperative MGC imaging allowed visualization after clearing of lymphatic pooling. What was seen as a hot spot on FGC was confirmed to be a false positive with the MGC. |

| 14 | Detected a hot spot that was seen by the FGC and missed by the probe (Fig. 4) |

DISCUSSION

The current study summarizes a pilot experience with a mobile gamma camera. Intraoperative imaging with an MGC offers the following opportunities: (1) imaging of SLNs near an injection site, after wide excision of the injection site; (2) imaging of an entire lymph node basin after removal of 1 or more SLNs, to determine whether additional sentinel nodes exist, (3) reimaging of the patient in the operating room to clarify ambiguous views at FGC imaging, (4) live imaging of a node basin to guide SLN identification when the patient position may differ from that at the time of FGC imaging, (5) confirmation of handheld probe imaging to clarify false positives from the FGC imaging, and (6) formal documentation of intraoperative findings. The experience in the current study supports the usefulness of MGC imaging, manifest in these 6 advantages. In 15 of the 20 patients, identification of SLNs using the conventional combination of FGC imaging and the handheld probe was uncomplicated, and the MGC did not provide specific advantages over the conventional technique. However, in 5 of the 20 patients, there were documented advantages, and this benefit in 25% of patients supports continued investigation and optimization of the MGC system.

The handheld gamma probe used intraoperatively has only a single detector. In experienced hands, it works well, and it certainly is a valuable tool. However, it has several limitations: it does not provide imaging documentation for the medical record; its usefulness is very dependent on correct probe positioning and thus is very operator-dependent, and its counting rate is very dependent on the distance between the probe tip and the node, changing approximately as the inverse of the distance squared. Sentinel nodes with “ex vivo” counting rates that are 10% or more of the counting rate of the hottest node may contain metastases even when the hotter nodes are negative,23 a finding that supports our standard practice of excising SLNs until the residual bed count is less than 10% of that of the hottest node. When this determination is made with the handheld probe, if the probe is even a few millimeters away from a residual sentinel node, it will incorrectly record the activity as being artificially less than it is, thus possibly leaving a true sentinel node in situ. A distinct advantage offered by the MGC equipped with a parallel hole collimator is that its sensitivity for detection of radioactivity signal does not significantly change over the range of node-to-camera distances used in the operating room. We found in one patient that a sentinel node was missed with the gamma probe (its activity was deemed too low for excision by the probe) but was detected with the MGC, as an example highlighting this value of the MGC.

We found in our pilot study that the MGC was efficient to use and provided us with assurance of complete SLNB by the end of the surgical case and with excellent documentation. Another approach being investigated to improve localization of SLN is SPECT/CT imaging. It can provide high-resolution images preoperatively and may well be a useful replacement for FGC imaging, though likely more expensive. However, it does not provide the advantages of intraoperative imaging that are available with an MGC.

In this pilot study, the MGC detected the 2 hot spots that were missed by the FGC in preoperative imaging and the MGC detected the single hot spot that was missed by the probe intraoperatively.

Although this pilot study demonstrated a sensitivity for SLN detection by the MGC of 93% (90% CI, 84%–98%), which is encouraging, 3 SLNs were not detected by the MGC. Factors that may affect MGC sensitivity for nodal detection include camera sensitivity, ability to correctly position the camera, and total radioactivity levels in the nodes. Notably, all 3 of the missed SLNs were in participants injected the day before the day of surgery (with an over 20-hour time-lapse between injection and MGC imaging in all cases); thus, they had significantly lower total activity in their nodes than patients injected on the day of surgery. The average probe count for the patients imaged on the same day as injection was 14,065 compared with an average of 5291 for patients imaged on the day after injection. This finding suggests the potential advantage of tracer injection shortly before surgery followed by preoperative MGC scanning to eliminate the need for injection and FGC imaging the previous day. This would also reduce logistical complications for the patient and simplify operating room scheduling.

This pilot study highlighted the need for fast and easy maneuverability of the MGC device in the operating room. Although the current gantry arm allows for horizontal or vertical movement, pivoting the camera in some directions is a challenge that limits the surgeon’s ability to obtain anterior-oblique views and to maneuver the MGC in the tight axillary space. Given that increased operating time comes at a significant financial cost and increased anesthesia time, being able to move the system quickly in and out of the surgical field is critical. Accordingly, before MGC imaging is incorporated into standard practice, the device will be modified to improve maneuverability under sterile conditions.

In summary, data from this pilot study support the safety, feasibility, and sensitivity of the 13 cm × 13 cm MGC evaluated in this study. In addition to these findings, the MGC was clinically useful in 5 (25%) of the 20 participants when used in addition to standard practice, by facilitating SLN identification in the setting of ambiguous FGC images, by identifying a node missed by standard evaluation, or by clarifying that residual radioactivity did not represent a true SLN. We believe that the benefit of the MGC will initially be greatest in cases where SLN drainage patterns are variable (ie, midline lesions on the trunk, head, and neck) or when there are multiple hot spots in a single drainage basin. In this trial, that represented 14 (70%) of the 20 cases. For example, in the 7 melanomas of the trunk included in this study, 2 drained to 2 separate lymph node basins and 1 drained to 3 separate lymph node basins, supporting the complexity of drainage patterns in these cases. Together, these findings support further investigation of the MGC for intraoperative use, with the intent of increasing the accuracy of SLN biopsy, minimizing morbidity, and speeding intraoperative localization in complex cases.

FIGURE 3.

In participant 12, the handheld gamma probe identified an apparent residual node whose activity was 13% of that of the hottest node. MGC camera imaging revealed that what appeared to be a single hot spot (A) was in fact 3 separate spots (B) that individually did not meet the activity criteria for sentinel nodes.

FIGURE 4.

An atypical location for an SLN, adjacent to injection site in the left upper arm of the patient. This hot spot was identified in the FGC (A) but questioned by the nuclear medicine team. It was not found with initial evaluation with the handheld probe. There was a suggestion of the hot spot on the first MGC image (B) and with rotation of the camera around the arm (C) the hot spot was clearly seen. The node was removed and was hot.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Cardiovascular Surgery Research Training grant (T32 HL007849) to L.T.D. and by Jefferson Lab in Newport News, Va.

L.T.D. is primary party responsible for data collection and analysis and drafting and revising of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. M.J.M. worked with the surgical team in the operating room to assist with data collection, in addition to contributing toward image data analysis, and contributed to the revisions of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. P.G.J. worked with the surgical team in the operating room to assist with data collection, in addition to contributing toward image data analysis, and contributed to the revisions of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. G.R.P., primary statistician, contributed significantly to the design of the study, the analysis of the data, and the results section of the manuscript, and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. M.E.S., additional statistician, contributed significantly to the analysis of the data and the drafting of the results section of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. P.K.R., division head of nuclear medicine, contributed significantly to the design of the study and the analysis of the gamma probe data and also participated in the revision of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. S.M. was responsible for the development of the customized gamma camera used in this study and contributed significantly to data collection in the operating room and also contributed to the revisions of the manuscript and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. M.B.W. contributed significantly to the design of the pilot study, including the scientific methods and logistical details, participated in the initial drafting of the manuscript and revisions, and gave final approval for the manuscript publication. C.L.S. Jr, lead investigator on the design of the study, performed all surgical cases and assisted with data collection in the operating room, participated in the initial drafting of the manuscript and revisions, and gave final approval for the manuscript publication.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial disclosure: There are no financial disclosures to report for this manuscript.

Commercial sponsorship: There was no commercial sponsorship for this study. Jefferson Lab in Newport News, Va, provided the mobile gamma camera for the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Testori A, De Salvo GL, Montesco MC, et al. Clinical considerations on sentinel node biopsy in melanoma from an Italian multicentric study on 1,313 patients (SOLISM-IMI) Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(7):2018–2027. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karim RZ, Scolyer RA, Li W, et al. False negative sentinel lymph node biopsies in melanoma may result from deficiencies in nuclear medicine, surgery, or pathology. Ann Surg. 2008;247:1003–1010. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181724f5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caraco C, Marone U, Celentano E, et al. Impact of false-negative sentinel lymph node biopsy on survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2662–2667. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clary BM, Mann B, Brady MS, et al. Early recurrence after lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in patients with primary extremity melanoma: a comparison with elective lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:328–337. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathelin C, Salvador S, Huss D, et al. Precise localization of sentinel lymph nodes and estimation of their depth using a prototype intraoperative mini gamma-camera in patients with breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:623–629. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.036574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathelin C, Salvador S, Croce S, et al. Optimization of sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer using an operative gamma camera. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:132. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcan P, Ibis E, Aras G, et al. Identification of sentinel lymph node in stage I–II breast cancer with lymphoscintigraphy and surgical gamma probe: comparison of Tc-99m MIBI and Tc-99m sulfur colloid. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:317–321. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000159528.12028.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern KA, Rosenberg RJ. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy during lymphatic mapping for breast cancer: improved sentinel node imaging using subareolar injection of technetium 99m sulfur colloid. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van dP I, Olmos RA, Kroon BB, et al. The hidden sentinel node and SPECT/CT in breast cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:6–11. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olmos RA, Vidal-Sicart S, Nieweg OE. SPECT-CT and real-time intraoperative imaging: new tools for sentinel node localization and radioguided surgery? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Lievshitz G, et al. Lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node mapping using a hybrid SPECT/CT system. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belhocine TZ, Scott AM, Even-Sapir E, et al. Role of nuclear medicine in the management of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:957–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uren RF. SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphy to locate the sentinel lymph node in patients with melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(6):1459–1460. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0463-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Law M, Cheng KC, Wu PM, et al. Patient effective dose from sentinel lymph node lymphoscintigraphy in breast cancer: a study using a female humanoid phantom and thermoluminescent dosemeters. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:818–823. doi: 10.1259/bjr/57254925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez F, Fernandez MM, Gimenez M, et al. Performance tests of two portable mini gamma cameras for medical applications. Med Phys. 2006;33:4210–4220. doi: 10.1118/1.2358199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barranger E, Kerrou K, Pitre S, et al. Place of a hand-held gamma camera (POCI) in the breast cancer sentinel node biopsy. Breast. 2007;16:443–444. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scopinaro F, Tofani A, di SG, et al. High-resolution, hand-held camera for sentinel-node detection. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008;23:43–52. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarsvold JN, Greene CM, Mintzer RA, et al. Intraoperative gamma imaging of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. Phys Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):76–79. doi: 10.1016/S1120-1797(06)80030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchimochi M, Hayama K, Oda T, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of a small CdTe gamma-camera for sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:956–962. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buono S, Burgio N, Hamoudeh M, et al. Brachytherapy: state of the art and possible improvements. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:411–424. doi: 10.2174/187152007781058640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harlow SP, Krag DN, Ashikaga T, et al. Gamma probe guided biopsy of the sentinel node in malignant melanoma: a multicentre study. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:45–55. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMasters KM, Reintgen DS, Ross MI, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: how many radioactive nodes should be removed? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:192–197. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]