SUMMARY

Exogenously-expressed opsins are valuable tools for optogenetic control of neurons in circuits. A deeper understanding of neural function can be gained by bringing control to endogenous neurotransmitter receptors that mediate synaptic transmission. Here we develop a comprehensive optogenetic toolkit for controlling GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in the brain. We synthesized a series of photoswitch ligands and the complementary genetically-modified GABAA receptor subunits. By conjugating the two components we generated light-sensitive versions of the entire GABAA receptor family. We validate these light-sensitive receptors for applications across a broad range of spatial scales, from subcellular receptor mapping to in vivo photo-control of visual responses in the cerebral cortex. Finally, we generated a knock-in mouse in which the “photoswitch-ready” version of a GABAA receptor subunit genomically replaces its wild-type counterpart, ensuring normal receptor expression. This optogenetic pharmacology toolkit allows scalable interrogation of endogenous GABAA receptor function with high spatial, temporal, and biochemical precision.

INTRODUCTION

GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, acting in counter-point to glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter. The delicate balance between GABAergic inhibition and glutamatergic excitation is essential for normal sensory processing, motor pattern generation, and cognitive function. Abnormalities in GABA-mediated inhibition have devastating consequences, contributing to pathological pain (Zeilhofer et al., 2012), movement disorders (Galvan and Wichmann, 2007), epilepsy (Treimain, 2001), schizophrenia (Guidotti et al., 2005), and neurodevelopmental disorders (Ramamoorthi and Lin, 2011).

GABA exerts its effects largely through ligand-gated Cl− channels known as GABAA receptors (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). GABAA receptors are heteropentamers containing two α, two β, and one tertiary subunit. The α-subunit contributes to GABA binding and determines gating kinetics and subcellular localization of the receptor (Olsen and Sieghart, 2009; Picton and Fisher, 2007; Rudolph and Mohler, 2014). There are six α-subunit isoforms expressed differentially during development (Laurie et al., 1992) and across brain regions (Wisden et al., 1992), but the distinct functions of individual isoforms remain elusive.

Pharmacological agents, including agonists, competitive antagonists, and allosteric modulators, have been the main instruments for elucidating the function of GABAA receptors. However, these tools are limited by the low spatial and temporal precision of drug application. Moreover, accurate manipulation of GABAA isoforms has been hindered by the lack of subtype-specific agonists or antagonists for the GABA-binding site. There are subtype-selective allosteric modulators for the benzodiazepine-binding site, but they have limited specificity and/or low efficacy (Rudolph and Mohler, 2014). Gene knock-out technology provides an alternative strategy for deducing the function of GABAA isoforms, but removal of one α-subunit can lead to compensatory changes in the expression of other receptors and ion channels (Kralic et al., 2002; Ponomarev et al., 2006; Brickley et al., 2001).

For these reasons, we have developed an optogenetic pharmacology strategy that enables isoform-specific photo-control of the entire GABAA receptor family, and by extension, all GABAA-mediated inhibition in the brain. We show that photo-control can be implemented at all levels, from investigating subcellular receptor distribution to regulating visual cortical activity in vivo. Finally, we introduce a transgenic mouse that allows, for the first time, photo-control of an endogenous neurotransmitter receptor. Instead of controlling an exogenous optogenetic tool that over-powers the native electrophysiology of neurons (e.g. NpHR or Arch; Zhang et al., 2011), our approach allows direct manipulation of the brain's own GABAA receptors, a powerful strategy for understanding the roles that they play in health and disease.

RESULTS

The LiGABAR Toolkit

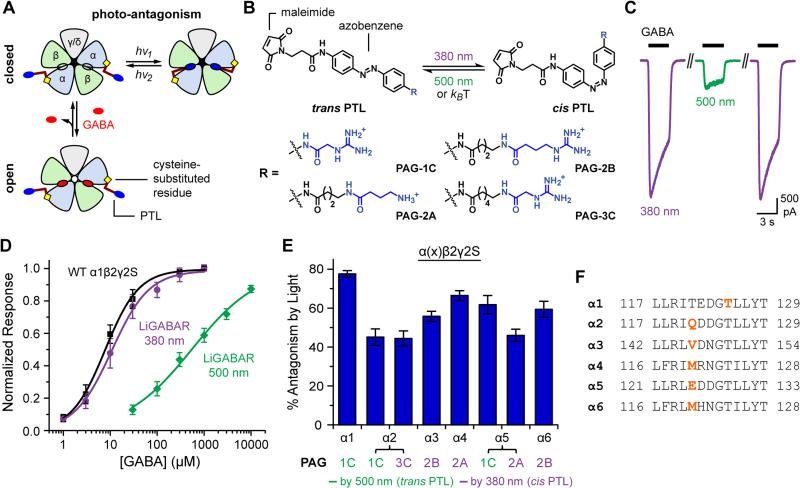

The GABAA receptor has two GABA-binding sites, each at the interface of α and β subunits (Figure 1A). LiGABAR is generated by conjugating a photoswitchable tethered ligand (PTL) onto a cysteine genetically engineered into the α-subunit near the GABA-binding site. The PTL molecule has three chemical modules (Figure 1B): a cysteine-reactive maleimide group (for receptor conjugation), an azobenzene core (for photoswitching), and a GABA-site ligand (for competitive antagonism). The azobenzene adopts an extended trans configuration in darkness and a twisted cis configuration in 360-400 nm light. The cis isomer slowly reverts to the trans form in darkness, but this process can be accelerated with 460-560 nm light. Hence photo-control is bi-directional. Depending on where the PTL is attached, either the cis or the trans isomer antagonizes the receptor, and photoswitching to the alternative configuration alleviates antagonism (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Optogenetic Toolkit for the GABAA Receptor Family.

(A) The operating principle of LiGABAR. A PTL is conjugated onto the α-subunit near the GABA-binding site. Isomerizing the PTL with two different wavelengths of light prevents or allows GABA binding, thereby controlling whether the receptor can be activated to open the chloride-conducting channel.

(B) PTLs consist of a cysteine-reactive maleimide group, a photosensitive azobenzene core, and a GABA-site ligand (blue; linked to azobenzene directly or via a short spacer).

(C) Photo-control of a representative LiGABAR (PAG-1C conjugated α1T125C, co-expressed with the wild-type β2 and γ2S). Currents were elicited by 30 μM GABA in 380 nm (violet) or 500 nm (green) light.

(D) α1-LiGABAR functions like the wild-type receptor in 380 nm and is strongly inhibited in 500 nm. Data points are mean ± SEM. Dose-response curves are fits to the Hill Equation. Black: wild-type, 7 cells; violet: LiGABAR/380 nm, 6 cells; green: LiGABAR/500 nm, 4 cells.

(E) Quantification of LiGABAR photosensitivity for each α-isoform. Currents were elicited by GABA at ~EC50 of the wild-type receptors (see [GABA]test values in Figure S2). Photosensitivity is described as the percent decrease of peak current by photo-antagonism. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 4-6).

(F) The PTL attachment site for each α-isoform. The sequences of loop E in rat α1-α6 subunits are aligned. Sites for cysteine substitution are shown in bold orange.

Recordings for (C)-(E) were carried out in HEK cells held at −70 mV. See also Figures S1-S3.

We previously developed PTLs with muscimol as the ligand (linked to azobenzene via N-acylation; Lin et al., 2014). While these compounds do impart light sensitivity on GABAA receptors, their low efficacy limited the magnitude of photoswitching in vitro, and their poor solubility (<50 μM) excluded the use in vivo. To improve efficacy, we made new PTLs with either GABA or its guanidinium analogs as the ligand (Figures 1B and S1). We expected that these PTLs would be antagonists like other ester or amide derivatives of GABA (Matsuzaki et al., 2010). The diffuse positive charge of the guanidinium group may enhance ionic, hydrogen-bond, and/or cation-π interactions with the receptor (Bergmann et al., 2013; Miller and Aricescu, 2014), and protonation of amino/guanidine group at neutral pH should enhance water solubility of the PTLs.

The new PTLs were conjugated onto a series of cysteine mutants of α1 (Figure S1), co-expressed with wild-type β2 and γ2 in HEK-293 cells. The optimal combination of PTL and cysteine mutant was PAG-1C (Figure 1B) and α1T125C (Figures 1C-1F and Figure S1). As expected, the GABA-elicited current was strongly reduced in 500 nm (trans PTL) and completely restored in 380 nm light (cis PTL; Figure 1C). Cis-to-trans photoisomerization reduced the response to half-saturating GABA by 78 ± 2% (10 μM, n = 6; Figure 1E), and to saturating GABA by 57 ± 2% (300 μM, n = 6). Dose-response curves showed that the EC50 increased from 15.3 ± 6.0 μM (n = 6) to 583 ± 139 μM (n = 4) when the PTL was switched from cis to trans (Figure 1D), consistent with the induction of competitive antagonism. Receptor activation was indistinguishable from wild-type with the PTL in the cis configuration (wild-type EC50 = 9.5 ± 2.3 μM, n = 7, p > 0.1, two-tailed t test). Taken together, the discovery of PAG-1C for α1-LiGABAR validates the PTL design and establishes effective photo-control of this receptor isoform.

We next applied the PTL strategy to all other α-isoforms (α2-α6) to obtain the complete LiGABAR toolkit. We paired cysteine mutants of α-subunits (focusing on loop E, where α1T125C is located) with a library of PTLs, and the resulting LiGABARs were evaluated in HEK-293 cells. These PTLs varied in their ligands (GABA, guanidinylated GABA, and guanidine acetic acid; Figure S1) and spacer lengths between the ligand and the azobenzene. For each isoform we selected the best PTL/mutant pair (Figures 1E and 1F and Figure S2) based on two criteria: (1) GABA-elicited currents are robustly photo-controlled (preferably ≥50% photo-antagonism at EC50), and (2) receptor function is unaffected by cysteine mutation and PTL conjugation.

Notably, we found a homologous mutation site that enables the reversed polarity of photo-control (i.e. antagonizing the receptor by cis PTL). When a longer PTL (e.g. PAG-2A, PAG-2B, or PAG-3C in Figure 1B) is conjugated onto this site, GABA-elicited current is reduced in 380 nm light by 45-70% and is fully restored in 500 nm light (Figures 1E and 1F for α2-α6; 48 ± 5% reduction by PAG-3C on α1T121C, n = 3). Interestingly, some of the mutants enable either cis or trans mode of photo-antagonism when conjugated with a longer or a shorter PTL, respectively (e.g. α2 and α5 LiGABARs in Figure 1E). This dual-option adds flexibility in whether or not the receptor will be turned off in the ground state (i.e. in darkness), an important consideration for applications in neural circuits.

Even though all of the receptors have a cysteine point mutation, this change appears to have minimal effects on receptor function, unless the PTL is conjugated and switched to the antagonizing configuration. None of the cysteine mutations, by themselves, alter receptor activation (Figure S2). Moreover, neither cysteine substitution nor PTL conjugation affects the characteristic properties of the parent receptor, such as allosteric modulation at the benzodiazepine site or anion permeability of the channel (Figure S2). Hence LiGABARs function as their normal receptor counterparts, until the moment they are photo-antagonized by a conjugated PTL.

Wild-type GABAA receptors, which lack a properly positioned cysteine near the GABA-binding pocket, remain insensitive to light after PTL treatment (Figures S1 and S3). Moreover, PTL treatment does not confer light sensitivity onto GABAB receptors, glutamate receptors, or voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels (Figure S3), indicating that there are few, if any, acute off-target effects on proteins that govern the electrophysiology of a neuron.

Subcellular Mapping of GABAA-receptor Isoforms with Optogenetic Pharmacology

Isoforms of GABAA receptors can be immunolocalized in distinct compartments of a dissociated neuron (Brunig et al., 2002), but subcellular localization can be problematic in intact neural tissue with intertwined cells. Moreover, antibody labeling cannot differentiate functional receptors from those that might be silent. Functional GABAA receptors can be mapped with pinpoint accuracy via two-photon photolysis of “caged GABA” (Matsuzaki et al., 2010), but this method cannot differentiate receptor isoforms. Optogenetic pharmacology with LiGABARs can overcome these limitations by allowing discrimination between functional receptor isoforms.

To validate this idea, we mapped the functional distributions of α1- and α5-LiGABARs in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. The cysteine mutant of the α1- or α5-subunit (α1T125C or α5E125C) was virally co-expressed with GFP in a rat hippocampal slice. The transduced slice was then treated with PTL (PAG-1C), and fluorescent neurons were selected for whole-cell voltage-clamp recording. We monitored responses to uncaged GABA when LiGABARs were either antagonized (by 540 nm) or relieved from antagonism (by 390 nm). By measuring the ratio of responses in these two conditions, we reveal the contribution of a particular α-isoform to the uncaging response and control for potential sources of variability. Other control experiments demonstrate that the two-photon uncaging response was unaltered by the conditioning light for receptor photo-control (Figure S4A, validated in the absence of the PTL), and that the two-photon light used for uncaging did not affect the state of the LiGABAR (Figure S4B).

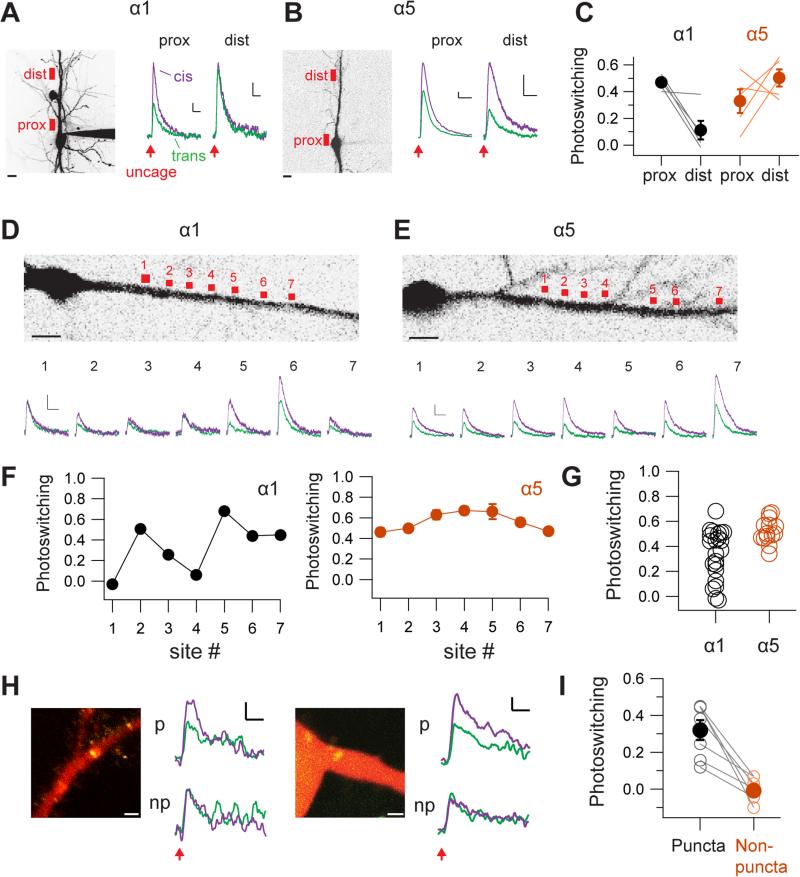

We first obtained a low-resolution view of where α1- and α5-LiGABARs are present (Figures 2A and 2B). Two locations were examined: one at or close to the soma (proximal site), and one on the primary apical dendrite (70-80 μm from soma; distal site). Each uncaging site spanned 7-10 μm. In cells expressing α1-LiGABAR, photoswitching (defined as the fraction of current antagonized by light) was more profound proximally than distally, with the effect decreasing from 0.47 ± 0.02 at the proximal site to 0.11 ± 0.07 at the distal site (p < 0.05, n = 5, paired t test; Figures 2A and 2C). In contrast, when α5-LiGABAR was expressed, photoswitching was not significantly different between the two sites (0.33 ± 0.09 at the proximal site and 0.50 ± 0.06 at the distal site; p > 0.1, n = 5, paired t test; Figures 2B and 2C). These results suggest that functionally active α1- and α5-GABAA receptors are differentially distributed, with α1 concentrated near the soma and α5 extending to more distal locations along the apical dendrite.

Figure 2. Mapping Subcellular Distributions of Specific GABAA Isoforms.

(A-C) Low-resolution mapping of α1- and α5-LiGABARs (both antagonized by trans PAG-1C) in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Left: Image of a neuron (filled with Alexa Fluor 594) expressing α1-LiGABAR. Red boxes indicate the proximal (prox) and distal (dist) locations for two-photon RuBi-GABA uncaging (800 nm, 5-10 ms). Scale bar = 10 μm. Right: Currents elicited by uncaging at 2 min after a 5-sec flash of 390 nm (violet) or 540 nm (green) light. Scale bars = 20 pA, 200 ms. Note that photoswitching is diminished at the distal site. (B) Measurements from a neuron expressing α5-LiGABAR. Note that photoswitching remains prominent at the distal site. (C) Group data of photoswitching at proximal and distal sites (5 cells for each isoform).

(D-G) Higher-resolution mapping of α1- and α5-LiGABARs along the apical dendrites. (D) Top: Image of soma and proximal dendrite from a neuron expressing α1-LiGABAR. RuBi-GABA was uncaged at 7 sites (each spanning 2-3 μm) along the dendrite. Bottom: Currents elicited at each site after 390 nm (violet) or 540 nm (green) conditioning flashes. (E) Measurements from a neuron expressing α5-LiGABAR. (F) Photoswitching (mean ± SEM) quantified for each uncaging site shown in (D) and (E). (G) Photoswitching values pooled from 22 and 18 uncaging sites in neurons expressing α1- and α5-LiGABAR, respectively (5 cells each). Scale bars = 50 pA, 500 ms.

(H-I) Probing the localization of α1-LiGABAR to inhibitory synapses. Experiments were carried out in cultured hippocampal neurons co-expressing α1-LiGABAR and GFP-fused gephyrin intrabody. Two-photon uncaging of RuBi-GABA was performed at single pixel resolution, either at GFP-positive puncta (p) or at adjacent GFP-negative locations (np). (H) Representative images and recording traces. Cells were filled with Alexa Fluor 594 (red). GFP-positive puncta (yellow) indicate the location of inhibitory synapses. Scale bars: 2 μm (images) and 2 pA, 100 ms (traces). (I) Group data (from 5 cells) showing that photoswitching of α1-LiGABAR is detectable only at GFP-positive puncta.

Neurons were held at 0 mV. Traces are averages from 3-5 trials. Photoswitching is calculated as the fraction of current photo-antagonized. For (C) and (I), individual measurements (average of each site) are plotted as open symbols, and the mean values for each group are represented by filled symbols (error bars = SEM).

We next obtained a higher resolution map of dendritic α1- and α5-LiGABARs with smaller, more closely spaced uncaging spots (2.5 μm, ~5 μm apart; Figures 2D and 2E). We found that the amplitude of GABA-elicited current varied between these spots in neurons expressing either α1 or α5. Independent of this, however, there was a striking difference in the spatial pattern of photoswitching between these two isoforms (Figures 2D-2G). Photosensitivity appeared to be localized to “hot spots” for α1 (Figures 2D and 2F), but distributed evenly along the dendrite for α5 (Figures 2E and 2F). Group data show higher spatial variability of photoswitching for neurons expressing α1-LiGABAR than for those expressing α5-LiGABAR, consistent with clustering of α1-containing receptors (coefficient of variation: 0.59 for α1 vs. 0.18 for α5, p < 0.05, Levene's test, n = 22 and 18 uncaging sites from 5 and 6 cells, respectively; Figure 2G).

Immunolabeling studies showed that the α1 isoform is concentrated at inhibitory synapses (Brunig et al. 2002; Kasugai et al., 2010). To verify that the photoswitching hot-spots of α1-LiGABAR represent clusters of functional receptor at synapses, we targeted inhibitory synapses using a genetically-encoded fluorescent intrabody for gephyrin (a scaffolding protein that tethers GABAA receptors at synapses; Gross et al., 2013). Neurons expressing the gephyrin intrabody exhibit fluorescent puncta at postsynaptic sites. We found significant photoswitching of responses only when GABA was uncaged at gephyrin puncta (0.32 ± 0.07 at puncta vs. −0.01 ± 0.03 at ~4 μm outside of puncta, n = 7 and 5 sites from 5 cells, respectively, p < 0.001, paired t test; Figures 2H and 2I). Hence by combining LiGABAR photo-control with two-photon uncaging, one can generate a functional map of a specific GABAA isoform on a neuron, resolved at the level of individual synaptic contacts.

Photo-control of Synaptic Inhibition with LiGABARs

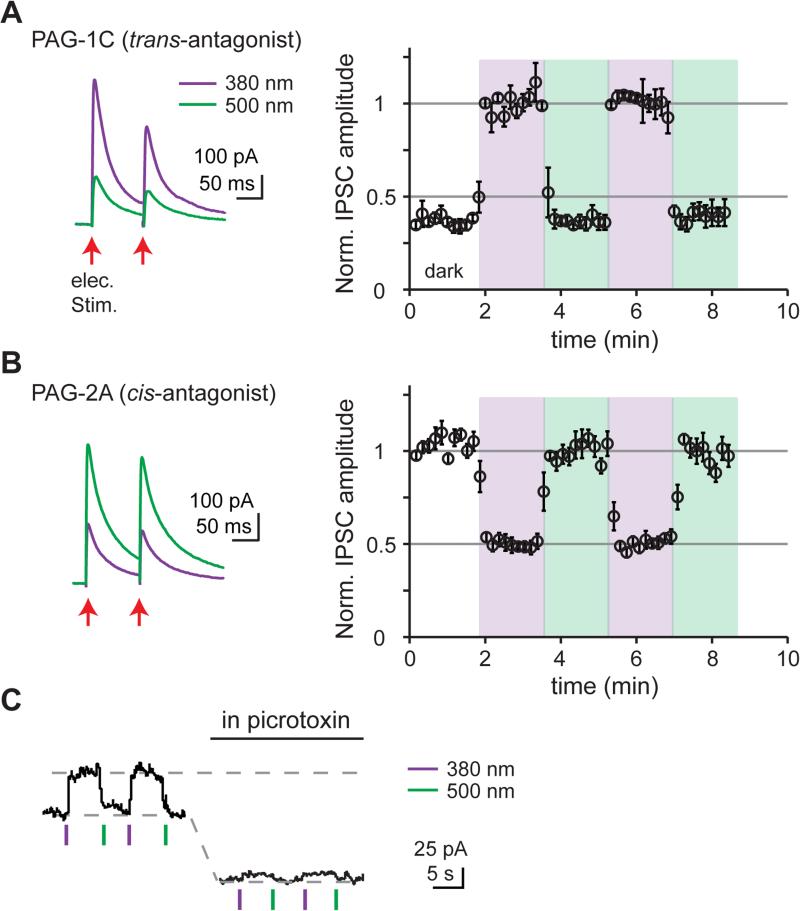

We next tested whether LiGABARs can enable photo-control of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). Mutant α-subunits were exogenously expressed by viral transduction in mouse cerebral cortex. Brain slices were treated with PTLs to generate LiGABARs. Monosynaptic IPSCs were evoked by electrical stimulation of local inhibitory inputs while blocking excitatory glutamate receptors.

When we employed a LiGABAR that exhibits trans-antagonism (PAG-1C on α1), we found that IPSC amplitude was 63 ± 3% smaller in 500 nm light than in 380 nm light (p < 0.05, n = 6, paired t test; Figure 3A). When we used a LiGABAR that exhibits cis-antagonism (PAG-2A on α5), we observed the opposite effect: IPSC amplitude was 52 ± 2% smaller in 380 nm light than in 500 nm light (p < 0.05, n = 6, paired t test; Figure 3B). Hence, synaptic inhibition can be photo-controlled with either polarity.

Figure 3. LiGABARs Enable Photo-control of Synaptic and Tonic inhibition.

(A) Photo-control of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) by a trans-antagonist (PAG-1C, conjugated to α1T125C). (B) Photo-control of IPSCs by a cis-antagonist (PAG-2A, conjugated to α5E125C). Light intensity was ~1 mW/cm2. Left: representative traces. Right: Changes in peak IPSC amplitudes in darkness (white), 380 nm (violet), and 500 nm light (green). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM. Note the opposite polarity of photo-control and the different default level of IPSC (in darkness) in (A) and (B). See also Figure S5.

(C) Photo-control of tonic currents by a trans-antagonist (PAG-1C, conjugated to α5E125C). Light intensity was 4.5 mW/mm2 for 390 nm and 28 mW/mm2 for 540 nm. Current levels were sustained after light flashes due to the bi-stability of LiGABAR (see Figure 4C). Photo-control was abolished after all of the GABAA receptors (including α5-LiGABAR) are blocked by picrotoxin (100 μM).

Recordings were carried out in cortical (A and B) or hippocampal (C) pyramidal neurons held at 0 mV.

In principle, the amplitude of IPSCs can be changed by altering presynaptic GABA release or postsynaptic GABAA receptors. To verify that our observed effects are entirely postsynaptic, we compared the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) at the two photoswitching wavelengths. Changes in PPR would reflect changes in presynaptic release probability (Zucker and Regehr, 2002). We found that PPR was the same under 380 and 500 nm illumination (0.9 ± 0.1 vs. 0.9 ± 0.1, p > 0.05, n = 11, paired t test), indicating that photoswitching was entirely a postsynaptic phenomenon.

Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors mediate tonic inhibition, important for setting the tone of excitability in the brain (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). To test whether LiGABARs enable photo-control of tonic inhibition, we recorded from hippocampal pyramidal neurons expressing α5-LiGABAR (conjugated with PAG-1C). To magnify GABA-mediated currents, neurons were clamped at 0 mV, far from ECl (−70 mV), and a small volume of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; ~30 mL) was re-circulated to avoid wash-out of extracellular GABA. Under these conditions, a brief flash of 390 nm light caused an outward current increase of 52 ± 13 pA (n = 5) that was reversed by 540 nm light (Figure 3C). The effect of light was abolished after applying picrotoxin (100 μM), confirming that it was mediated by GABAA receptors.

Our results suggest that viral expression of the LiGABAR mutant alone, in the absence of the photoswitch, did not significantly alter synaptic properties. We compared the ratio of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents (E/I ratio) in α1T125C-expressing vs. non-expressing neurons in cortical slices. The E/I ratio was the same in mutant-expressing neurons and in control neurons, and there was no difference in the kinetics of IPSCs between the two groups (Figure S5). Taken together, LiGABARs can be exogenously introduced into brain tissue without changing the balance between synaptic excitation and inhibition.

Kinetics of LiGABAR Photo-control

Optogenetic tools allow rapid manipulations of neuronal activities with temporal precision. To test the speed of LiGABAR photo-control, we measured the minimal illumination time required for full IPSC photoswitching in CA1 pyramidal neurons with α1-LiGABAR. A flash of 540 nm (28 mW/mm2) or 390 nm (4.5 mW/mm2) light was applied 100 ms prior to presynaptic stimulation to antagonize or restore the receptor, respectively. We first fully antagonized LiGABAR with a fixed duration of 540 nm light (500 ms) and restored receptor activity with various durations of 390 nm light (ranging from 10 ms to 500 ms; Figure 4A). Photoswitching (relief of antagonism) increased with increasing duration of 390 nm light, and approached maximal (>95 %) with a 100-ms flash. We next repeated the experiment with different durations of 540 nm light (and fixed 390 nm flashes; Figure 4A). In this case, photoswitching (induction of antagonism) approached maximal with a 200-ms flash of 540 nm light.

Figure 4. Kinetics of LiGABAR Photo-control.

(A) Violet: Illumination time required for restoring LiGABAR from antagonism. Pairs of IPSCs were recorded, one measured with a fixed duration of 540 nm (500 ms) and the other with a variable duration of 390 nm. Green: Illumination time required for imposing LiGABAR antagonism. The same measurements were made with a fixed duration of 390 nm (500 ms) and variable durations of 540 nm. Conditioning flashes were delivered 100 ms prior to synaptic stimulation. Inset: Representative photosensitive IPSC component (IPSC390 – IPSC500) from the same neuron receiving different durations of conditioning light. Fractional photoswitching was defined as the normalized photosensitive IPSC amplitude. Group data of fractional photoswitching (symbols; mean ± SEM) vs. flash duration were fit with single exponentials (curves). n = 2-4 cells.

(B) Photo-control of synaptically-stimulated action potential firing with a brief flash of light. With the neuron at rest (around −70 mV; current-clamp), a brief flash of conditioning light (colored squares) was applied 100 ms prior to Schaffer-collateral stimulation (triangles). A 100-ms flash of each conditioning light was sufficient for photo-controlling spike generation. Scale bar = 20 mV, 1 s. Green: 540 nm. Violet: 390 nm.

(C) Bi-stability of LiGABAR. Prior to illumination, LiGABAR was antagonized by the trans-PTL in darkness (a). The amplitude of IPSC increased upon the illumination of 380 nm (b), which then decreased slowly in darkness after the conditioning light was turned off (c). The amplitude of IPSC reduced to the initial level upon the illumination of 500 nm (d), which remained steady in darkness thereafter. The time course of IPSC decrease in darkness (post-380 nm) is fitted with a single exponential decay (red curve; τ = 30 ± 6 min) to depict the thermal relaxation of the cis-PTL. Scale bars = 50 pA, 50 ms.

Recordings were carried out in cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neurons expressing α1-LiGABAR.

We next tested whether rapid control of synaptic inhibition could change the spike output of a neuron in response to synaptic stimulation. Current-clamp recordings were carried out in CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing α1-LiGABAR. We electrically stimulated Shaffer collaterals, recruiting overlapping excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs that have opposite effects on spiking. Each stimulus elicited a single spike when LiGABAR was photo-antagonized. The spike was eliminated when LiGABAR was relieved from antagonism. The spiking response could be gated with a flash of light as brief as 100 ms, delivered immediately before the presynaptic stimulus (Figure 4B). Collectively, our results (Figure 4A and 4B) suggest that inhibition can be photo-controlled at a time scale of 100-200 ms. Because the speed of photo-control is largely determined by light intensity, LiGABAR manipulation may be accelerated further with a brighter light source.

LiGABARs can also be used as a bi-stable switch. To illustrate this feature, we monitored the IPSC amplitude after transient conditioning with 380 nm or 500 nm light (Figure 4C). The IPSC amplitude was elevated by 380 nm light, and slowly decreased upon returning to darkness with a time constant of 30 ± 6 min (95% confidence bounds: 26 ± 4 min and 38 ± 8 min; n = 4). Exposure to 500 nm light quickly reduced the IPSC back to the initial amplitude, where it remained steady over 10 min. Hence, LiGABAR can be stably toggled between antagonized and antagonism-relieved states with brief flashes of conditioning light. This feature minimizes photo-toxicity and enables the use of other optical manipulations in the same experiment (e.g. GABA uncaging; Figure 2).

Spatial Reach of LiGABAR Photo-control in the brain

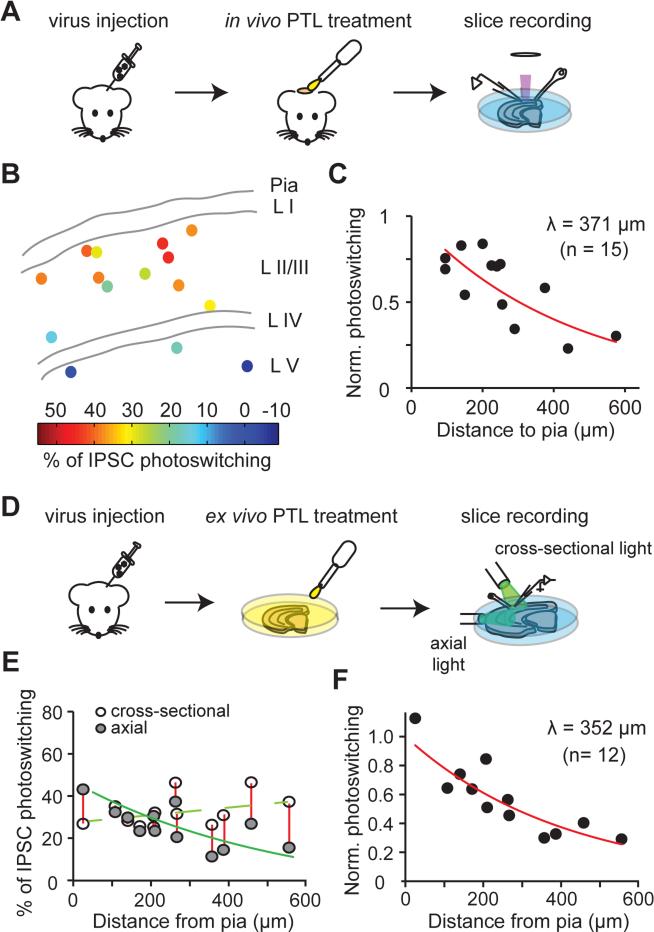

Before implementing LiGABAR in vivo, we needed to define how far the PTL and the light can penetrate through brain tissue to enable photo-control. We first determined how deep into the cerebral cortex the PTL can penetrate to form LiGABAR (Figures 5A-5C). To evaluate this parameter, we first expressed the mutant α-subunit by stereotactically injecting a virus (encoding α1T125C and eGFP) into mouse visual cortex. After 10-14 days, the mouse was anesthetized, and a craniotomy was performed to expose the cortex where neurons expressed the mutant receptor. Following the subsequent duratomy, a droplet of aCSF containing the PTL (250 μM PAG-1C) was applied onto the exposed brain surface (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Accessible Depth of LiGABAR Photo-control from the Surface of the Brain.

(A) Strategy for measuring the penetration depth of a PTL into an intact brain.

(B) Map of the depth-dependence of IPSC photoswitching. Each point indicates the location of a recorded cell in cortical layers (L1-L5), with the magnitude of IPSC photoswitching color-coded.

(C) Depth-dependent decrease in IPSC photoswitching (n = 15 cells). The data were normalized and fit with an exponential decay to calculate the depth constant (λ) of PTL penetration from the brain surface.

(D) Strategy for estimating the penetration depth of light into the brain. The axial light mimicked the in vivo illumination (with light penetrating into the brain from the pia surface). The cross-sectional light photo-controlled LiGABARs regardless of the cell position, providing a scale factor for estimating the effectiveness of the axial light.

(E) Depth-dependence of IPSC photoswitching, with either axial or cross-sectional illumination.

(F) Depth-dependent decrease in IPSC photoswitching. The data (ratio of axial vs. cross-sectional photoswitching from 12 cells) were normalized and fit with an exponential decay to calculate the depth constant (λ) of photoswitching from the brain surface.

The virus used in these experiments encodes mutant α1T125C and eGFP. PTL = PAG-1C.

After one hour of treatment, we prepared cortical slices and recorded from GFP-positive neurons at various depths beneath the craniotomy region. The degree of IPSC photoswitching was assessed as an index of LiGABAR formation. We found that the degree of IPSC photoswitching declined with the depth from the pia, decreasing from ~40% near the surface to ~0% at 400 μm away from the surface (Figure 5B). This decline in IPSC photosensitivity could be fit with a single exponential function with a depth constant of 371 μm (95% confidence bounds: 239 μm and 824 μm; n = 15 cells from 3 mice; Figure 5C).

We next used a brain slice as a surrogate for intact brain tissue to evaluate how far the light can penetrate to photo-control LiGABAR (Figures 5D-5F). We prepared acute cortical slices from virally transduced mice, and incubated the slices in PTL-containing aCSF to allow uniform receptor conjugation. In each neuron, we measured the ratio of IPSC photoswitching under two different illumination conditions: first, with light projected directly into the slice axially from the pia surface and second, with light projected directly onto the slice in cross-section (Figure 5D). Axial illumination should photo-control LiGABAR maximally near the pia surface where light intensity is the highest. Cross-sectional illumination should photo-control LiGABAR uniformly, with variability attributable to other factors, such as differences in the expression of the mutant subunit. Hence the ratio of IPSC photoswitching by axial versus cross-sectional illumination reflects the efficiency of LiGABAR photo-control, calibrating for other factors that could cause cell-to-cell variation. We found that IPSC photoswitching by axial illumination decreased from ~41 % near the pia surface to ~11% at ~400 μm from the surface (Figure 5E). The depth-dependent decrease of photoswitching ratio (axial vs. cross-sectional) could be fit with a single exponential function with a depth constant of 352 μm (95% confidence bounds: 255 μm and 568 μm; n = 12 cells from 3 mice; Figure 5F). These experiments utilized an unfocused light source for axial illumination, which emitted at ~15 mW/cm2 for both wavelengths of light. A brighter or more focused light source, or an implanted optrode system, should allow an even deeper photo-control.

Taken together, these experiments suggest that both the PTL and the light can effectively reach as deep as ~350 μm from the brain surface, extending through layer 2/3 of the mouse cerebral cortex.

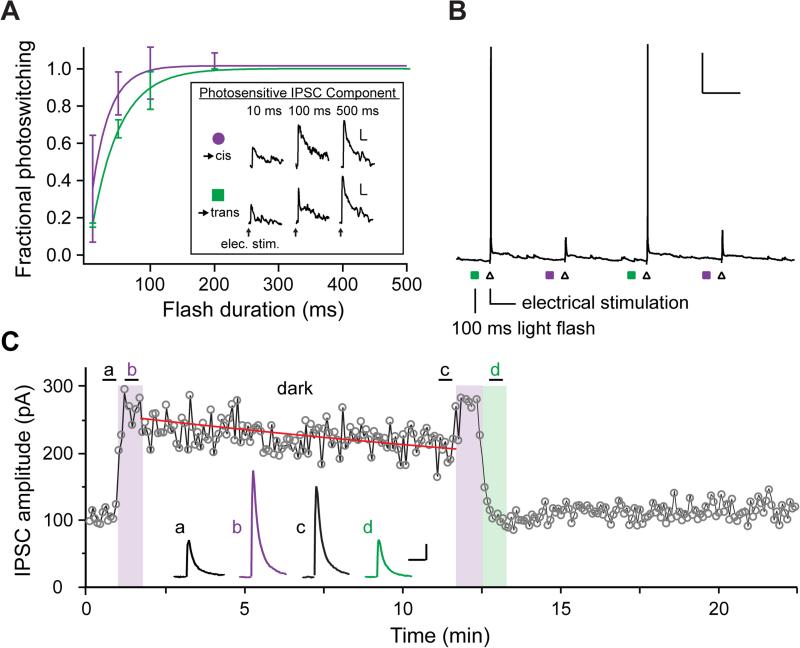

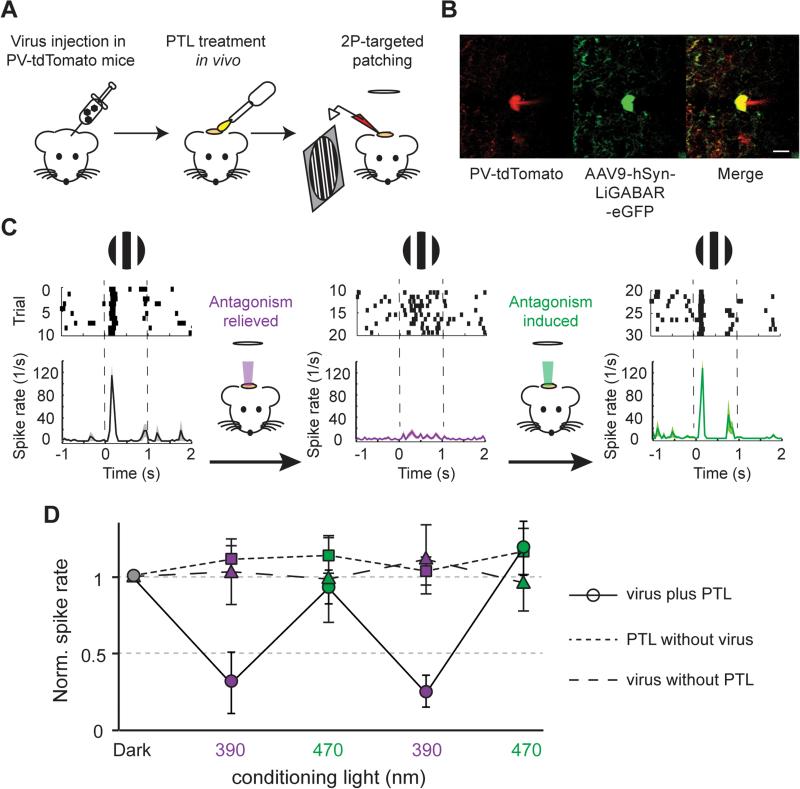

Photo-control of Cortical Visual Responses in vivo

Once we established that both the PTL and the light can penetrate into brain tissue to control inhibition at a sufficient depth, we tested whether photo-control is effective in vivo. Specifically, we asked whether photo-control of LiGABAR could alter information processing in the primary visual cortex (V1) of a mouse as it is responding to a visual stimulus (Figure 6). The LiGABAR mutant was virally introduced into mice two weeks before the experiments. After the mouse underwent anesthesia, craniotomy, and PTL treatment, we made extracellular loose-patch recordings from LiGABAR-expressing, parvalbumin-positive (PV+) interneurons in layer 2/3 (Figures 6A and 6B). We first confirmed that the visual stimulus, a 100% contrast drifting square grating, evoked spikes in the recorded neurons. To toggle LiGABAR between the antagonized and non-antagonized states, we delivered a full-field spot of conditioning light (390 nm or 470 nm) into the cortex through a microscope objective. Because LiGABAR is bi-stable (Figure 4C), a brief illumination of conditioning light (10 s) was sufficient to switch the receptor state for several minutes. This provided a time window for any spurious response to the conditioning light to decay before the onset of the visual stimulus.

Figure 6. In vivo Photo-control of Visual Responses in the Mouse Cortex.

(A) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedures.

(B) Two-photon image of a recorded PV+ neuron. The cell was identified by the co-expression of tdTomato (red, marker of PV+ cell) and eGFP (green, marker of LiGABAR expression).

(C) Experimental sequence. The raster plots and peristimulus time histograms show the spike activity of a PV+ neuron before any conditioning illumination (black), and after a 10-sec exposure to either 390 nm (violet) or 470 nm (green) light.

(D) Summary of visually evoked spike activities in PV+ neurons (circles), showing higher firing rates when LiGABAR was antagonized (dark and 470 nm) than when it was relieved from antagonism (390 nm). n = 7 cells from 4 mice. Control experiments with PTL treatment alone (squares; n = 6 cells from 2 mice) or viral injection alone (triangles; n = 9 cells from 2 mice) show no significant difference in spike activities after exposure to 390 nm vs. to 470 nm light. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM.

We found that the pattern of spiking in PV+ neurons, during the visual response, changed from burst-firing after conditioning with 470 nm light (antagonism induced) to sustained-firing after conditioning with 390 nm light (antagonism relieved; Figure 6C). Moreover, the average increase in spike rate during the visual stimulus was larger when LiGABAR was antagonized. Changes in spike rate evoked by the visual stimulus could be modulated up and down repeatedly by switching the conditioning light back and forth (n = 7 cells from 4 mice, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Figure 6D). Control experiments showed that neither the LiGABAR mutant alone nor the PTL alone enabled photo-control of visual responses (n = 6 cells from 2 mice, p > 0.05, oneway ANOVA; PTL alone, n = 9 cells from 2 mice, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Figure 6D). Taken together, these results show that LiGABAR can be introduced into a mouse brain for in vivo photo-control. Furthermore, our findings support the notion that GABAergic inhibition in PV+ neurons plays a role in information processing in the visual cortex, such as setting the gain and determining the temporal dynamics of the visual response (Katzner et al. 2011).

Genomic Substitution of a Wild-type GABAA α-isoform with the Photoswitch-Ready Mutant in a Knock-in Mouse

Our results suggest that in cortical pyramidal neurons, over-expression of a mutant α-subunit causes no significant changes in IPSC kinetics or E/I ratio (Figure S5). However, unadulterated expression in all neurons can only be assured by replacing the gene encoding the wild-type α-subunit with its mutant counterpart.

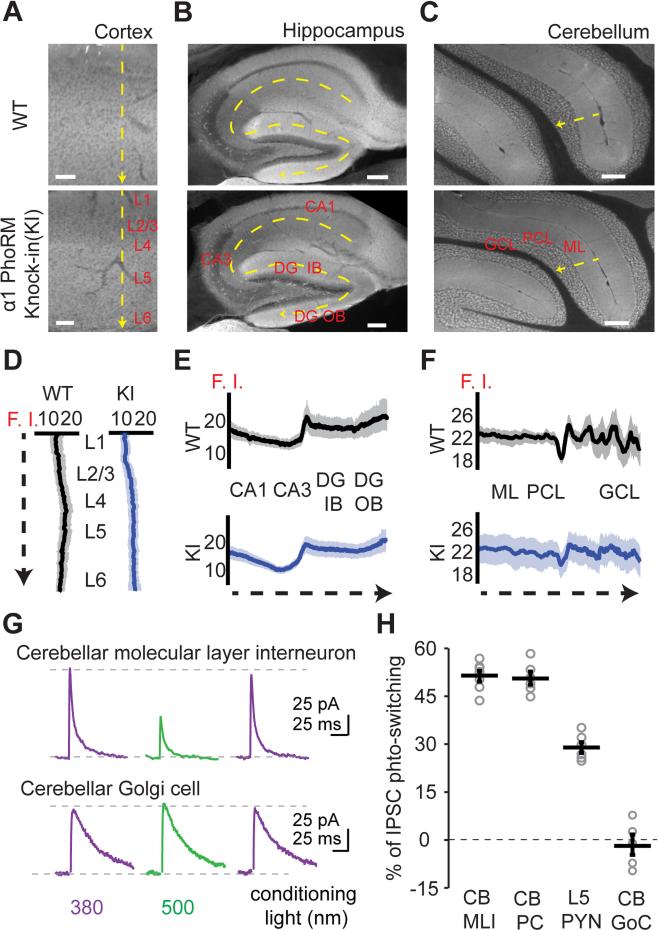

To bring about exact genomic substitution, we generated a knock-in mouse in which a single point mutation (T125C) was introduced into the gene of the α1-subunit through homologous recombination (Figure S6). We named this knock-in as the α1-GABAA Photoswitch-Ready Mutant (PhoRM) mouse. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed that the expression pattern of the mutant α1 was identical to that of the wild-type. Immunolabeling profiles through tissue slices from cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (Figures 7A-7F) were the same for the α1-GABAA PhoRM mouse as for the wild-type.

Figure 7. Characterizations of the α1-GABAA Photoswitch-ready Mutant (PhoRM) Knock-in Mouse.

(A-C) Fluorescent images of antibody labeling showing the expression pattern of the α1-subunit in the wild-type and the homozygous α1-GABAA PhoRM mice in visual cortex (A), hippocampus (B), and cerebellum (C).

(D-F) Quantification of α1 expression in different brain regions. Fluorescence intensity (F. I., in arbitrary unit) was measured along the yellow dash arrows in (A-C), showing similar expressing patterns between the wild-type and the α1-GABAA PhoRM mice in all of the three brain regions analyzed. In each genotype, the profiles were obtained from 2-3 sections in each mouse (2 wild-type and 3 knock-in mice).

(G) Representative recording traces from a cerebellar molecular layer interneuron and a Golgi cell of the α1-GABAA PhoRM mouse, showing differential photo-control of IPSC in these cell types.

(H) Scatter plots summarizing the magnitude of IPSC photoswitching in different types of neurons. CB: cerebellum. MLI: molecular layer interneuron. PC: Purkinje cell. GoC: Golgi cell. PYN: pyramidal neuron.

Group data are presented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S6.

Functionally, we examined the expression of α1T125C by measuring IPSC photoswitching in PAG-1C treated brain slices. We compared photoswitching in neuronal cell types that differ in the relative abundance of α1 with respect to other α isoforms (Figures 7G and 7H). We used cell types thought to express only the α1-isoform (cerebellar molecular layer interneurons (MLIs) and Purkinje cells (PCs); Eyre et al., 2012; Fritschy et al., 2006), a cell type that expresses α1 along with other isoforms (pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of cerebral cortex (L5 PYNs); Ruano et al., 1997), and a cell type devoid of α1 (cerebellar Golgi cells (GoCs); Fritschy and Hohler, 1995). Photoswitching was the strongest in MLIs and PCs (51 ± 2% and 50 ± 2%, n = 7 and 6 cells from 2 and 3 mice, respectively), intermediate in L5 PYNs (30 ± 2%, n = 6 cells from 2 mice), and non-existent in GoCs (−2 ± 3%, n = 5 cells from 3 mice). Hence the degree of photoswitching is correlated with the relative abundance of α1 in a neuron.

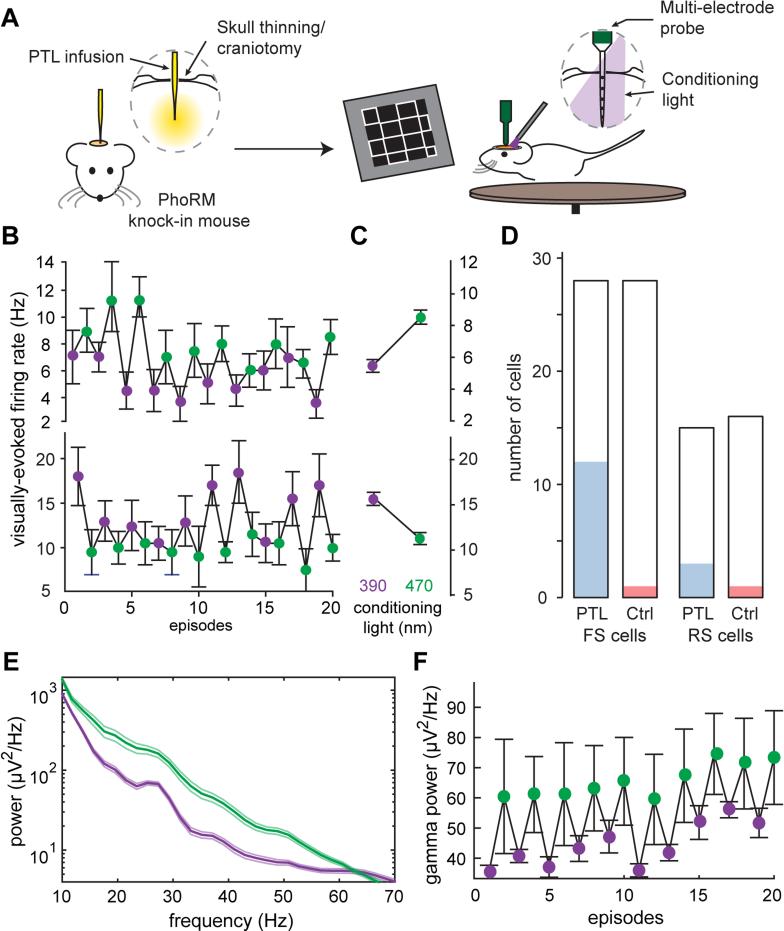

Photo-control of Sensory Responses and Gamma Oscillations in the α1-GABAA PhoRM Mouse

Understanding the role of inhibition in the cortex has often relied on non-specific blockers or antagonists of GABAA receptors. The α1-GABAA PhoRM mouse provides the unprecedented opportunity to selectively and reversibly remove a particular endogenous receptor from a functional neural circuit both in vitro and in vivo. We used a multi-electrode probe to record extracellular spiking activity in neurons in the visual cortex of the awake α1-GABAA PhoRM mouse. We applied the PTL by intracranial infusion through a micropipette inserted ~275 μm into the cortex (Figure 8A), an alternative approach to topical application on the brain surface.

Figure 8. In vivo Photo-control of Visually-evoked Responses and Gamma Oscillations in the Awake α1-GABAA PhoRM Mouse.

(A) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedures.

(B) Top: A neuron with an increased firing rate when α1-LiGABAR was antagonized (green points), compared to its firing rate when α1-LiGABAR was relieved from antagonism (violet points). Bottom: A neuron with a decreased firing rate when α1-LiGABAR was antagonized.

(C) Average firing rates from (A) and (B) in each illumination condition (20 episodes per condition).

(D) Summary of all of the cells recorded in PTL-treated (PTL) and vehicle-treated (Ctrl) α1-GABAA PhoRM mice. The number of cells that have significant photoswitching in firing rate is shown in blue for the PTL group and in red for the Ctrl group. See Figure S7 for the classification of FS (fast spiking) and RS (regular spiking) cells.

(E) Example power spectrum of local field potential in one of the PTL-treated α1-GABAA PhoRM mice. Photo-antagonizing α1-LiGABAR in vivo (green) increased the power of visually-evoked γ oscillations, compared to the γ power when antagonism was relieved (violet).

(F) Example recording of γ power (averaged between 20-60 Hz) in episodes when α1-LiGABAR was antagonized (green points) and in those when the receptor was relieved from antagonism (violet points).

Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

We examined the response of neurons to a visual stimulus train which consisted of 10 full contrast checkerboard images. We applied brief conditioning flashes to switch α1-LiGABAR 5 sec before each episode of the stimulus train. In many neurons (15/43 cells in 3 PTL-treated mice, p < 0.05, Friedman test over episodes), conditioning flashes that either induced or relieved antagonism reliably changed visually-evoked spiking activity. Owing to its non-homogenous distribution pattern in the brain (Figure 7; Fritschy and Mohler, 1995), we surmised that photo-controlling α1-LiGABAR might result in heterogeneous effects on cortical neurons. Indeed, some neurons showed a significant increase in firing rate after photo-antagonism (top of Figures 8B and 8C), while other neurons showed a significant decrease (bottom of Figures 8B and 8C). Photoswitching occurred in a larger fraction of fast-spiking neurons (FS cells; 12/28) than regular spiking neurons (RS; 3/15) (Figure 8D; see classification of FS and RS cells in Figure S7). In control mice infused with vehicle alone, only 1/28 FS cells and 1/16 RS cells exhibited photosensitivity (2/44 cells in 2 mice, Friedman test over episodes, p < 0.05), confirming that spike modulation was specifically a consequence of LiGABAR photo-control.

FS cells have been identified as mostly PV+ interneurons (Averamnn et al., 2012), which express a high level of α1-containing receptors (Hu et al., 2014), whereas RS cell are largely pyramidal neurons, which express multiple α isoforms (Bosman et al, 2002). The bimodal effect of light is consistent with the inhibitory microcircuit of the cortex, which includes an extensive network of interneuron-interneuron synaptic connections. Hence spike rate in an interneuron will tend to decrease when its own GABAA receptors are more active, and increase when GABAA receptors on presynaptic interneurons are more active. Understanding when and where direct inhibition or disinhibition dominates in the circuit is an important question that LiGABAR will help to answer.

Gamma (γ) oscillations are thought to be mediated primarily by reciprocal interactions between excitatory and inhibitory (E-I) neurons or by reciprocal interactions within networks of inhibitory neurons (I-I) (Bartos et al., 2007; Buzskai and Wang, 2012). Consistent with a crucial role for GABA, non-selective blockade of all GABAA receptor isoforms dampens γ oscillations (Hasenstaub et al., 2005). Surprisingly, we observed the opposite effect when we photo-antagonized specifically α1-containing GABAA receptors: enhancement of the γ power (increase of 28 ± 10%, n = 3, Friedman test over episodes, p < 0.05; Figures 8E and 8F). Experiments on control mice infused with vehicle alone showed no significant change in the γ power (increase of 2 ± 1%, n = 4, Friedman test over episodes, p > 0.05; Figures 8E and 8F). Inhibitory synapses between PV cells (I-I connections) are highly enriched with α1-containing receptors (Klausberger et al., 2002). Hence our results support a crucial role of I-I in γ-rhythmogenesis.

DISCUSSION

LiGABAR Brings Optogenetic Control to the Synapse

LiGABAR, like other optogenetic tools, enables precise and accurate manipulation of signals in the nervous system. But instead of manipulating an exogenous conductance added to a neuron, the signal being manipulated by LiGABAR is generated from within, by an endogenous neurotransmitter receptor. This enables interrogation of endogenous receptor function across broad levels of neural organization, from the molecular and cell biology of GABAA receptors in individual neurons to the systems biology of GABAA receptors in brain regions.

In principle, an endogenous protein could be made light-sensitive by chemical modification with a synthetic photoswitch or by protein engineering with a light-sensitive module (e.g. the LOV domain; Gautier et al., 2014). In practice, only the chemical approach has been applied successfully to neurotransmitter receptors (Gautier et al., 2014; Kramer et al., 2013). Chemical photosensitization requires only a single amino acid substitution, allowing a receptor to retain its normal expression, trafficking, and activity. In contrast, light-sensitive domains are large (e.g. >100 amino acids for LOV), and splicing a bulky domain into a receptor is likely to alter or disrupt its function. Chemical modification, in this regard, may be the only feasible way to confer light-sensitivity onto an endogenous neurotransmitter receptor.

Our results show that conjugating a PTL onto a modified GABAA receptor occurs quickly and efficiently in the brain under physiological conditions. The PTL can be applied either on the exposed surface of the brain or infused into neural tissue. In principle, both the compound and light can be delivered to any part of the brain with an optrode containing both a capillary and an optic fiber (Berglind et al., 2014).

At the cellular level, LiGABARs can be used to dissect the functions of different GABAA isoforms within a neuron. Independent photo-control offers a way to compare the geographical distribution, synaptic vs. extrasynaptic localization, and the functional impact of different isoforms. For example, our uncaging results (Figure 2) suggest that the α1-isoform is concentrated at synapses while α5 is broadly distributed, consistent with prior observations by immunolabeling (Brunig et al., 2002; Kasugai et al., 2010).

At the network level, LiGABAR can help reveal the functional impact of inhibition in a neural circuit. For example, GABAA receptors mediate both presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition (Kullmann et al., 2005; Farrant and Nusser, 2005), but unraveling these processes can be difficult. Presynaptic inhibition can be detected by measuring a decrease in neurotransmitter release, but there is no surefire way to selectively manipulate presynaptic GABAA receptors without also affecting postsynaptic GABAA receptors. By genetically targeting LiGABAR to the presynaptic cell, photo-control can be exerted selectively, elucidating the impact of different forms of inhibition to circuit function and behavior.

At the organism level, the α1-GABAA PhoRM mouse offers the unique opportunity to reversibly and specifically photo-antagonize an endogenous neurotransmitter receptor in vivo, revealing its role in neural information processing and behavior. In principle, the same optical manipulation can be carried out with knock-in mice for all of the other isoforms, elucidating their individual functions both in the normal brain and in neurological diseases. Because of their absolute subtype-specificity in receptor photo-control, GABAA PhoRM mice may also be useful for target validation in drug discovery.

Practical considerations

Specificity

Control of LiGABAR is sufficiently specific, fast, and powerful to enable broad applications in neuroscience. Although some membrane proteins have free extracellular cysteines that could possibly be decorated by the PTL, we have detected no off-target electrophysiological effects on wild-type GABA receptors, glutamate receptors, or voltage-gated ion channels (Figure S3). Additional control experiments may be warranted for new applications of LiGABAR to rule out unintended consequences.

Light requirements

We have shown that α1-LiGABAR can be photo-controlled within 100 ms with an LED light source of ~5 mW/mm2 intensity (Figure 4). Brighter light could result in even faster photoswitching, as suggested by studies on light-gated glutamate receptors (Reiner and Isacoff, 2014). The optimal wavelengths for azobenzene photoswitching are 360-400 nm for trans-to-cis and 460-560 nm for cis-to-trans isomerization, but the action spectrum may be tuned via structural modifications on the azobenzene core (Izquierdo-Serra et al., 2014). Once switched to the cis state, the thermal stability of the PTL ensures that LiGABAR remains lodged in that state for >10 minutes in darkness (Figure 4). Brief intermittent flashes of 380 nm light (e.g. 200 ms at 1/min) can keep the PTL in the cis state indefinitely. For a trans-antagonist this is an important feature, because it ensures relief of antagonism in darkness until the onset of 500 nm light. For α2-α6, we have developed cis-antagonists such that the receptors operate normally in darkness and are antagonized only when exposed to 380 nm light.

Limitations to photo-control

Photo-antagonism of LiGABAR is strong, but it can never be absolutely complete even with saturating light. Several factors may contribute to incomplete photoswitching. Conjugation of the PTL might be incomplete, leaving some receptors insensitive to light. Alternatively, antagonism may be limited by the affinity of the PTL for the GABA-binding site. Thus a high concentration of GABA during synaptic transmission (Auger et al., 1998) might transiently out-compete the PTL. Moreover, most neurons express multiple α-isoforms of GABAA receptors, and only receptors incorporating the mutant isoform will be subject to photoswitching.

Gene delivery

The gene of mutant α-subunit can be over-expressed in a neuron, for example with a viral vector, or substituted for the wild-type gene, for example in a knock-in mouse. Viral expression can be directed to a specified cell type with a customized vector, whereas gene substitution will occur in all cell types in the knock-in mouse. If the experimental goal is to understand the physiological or behavioral function of a given α-isoform, then the knock-in mouse is preferable for preserving the normal expression profile. If the goal is to understand the function of an inhibitory connection in a neural circuit, then viral over-expression may be preferable for restricting photo-control to a particular locus in the circuit. Users will need to weigh the benefit of achieving cell-specific expression against the uncertainty of over-expression, which might alter the natural level or distribution of GABAA receptors. The CRISPR/Cas9 system allows gene substitution in terminally differentiated cells in vivo (Platt et al., 2014), and we look forward to the time when exact genomic substitution of any α-subunit can be achieved in an adult animal in a cell type-specific manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

The photoswitch compounds were synthesized as trifluoroacetate salts. The compounds were prepared as concentrated stocks (10-100 mM in anhydrous DMSO) and diluted in buffers for receptor conjugation (final DMSO concentration <1% v/v). AAV9 (1012-1013 vg/ml) encoding a mutant α-subunit (α1T125C or α5E125C), an eGFP marker, and a human synapsin-1 promoter was prepared by UC Berkeley Gene Delivery Module following the previously published procedures (Lin et al., 2014). The α1-GABAA PhoRM mice were generated by UC Davis Mouse Biology program. All experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations of the ACUC at the University of California, Berkeley. Group data are reported as mean ± SEM. Detailed experimental procedures and data analysis methods are available in the Supplemental Information.

Mutant Expression and PTL Treatment

Ex vivo procedures (HEK cells, cultured neurons, and brain slices)

HEK cells and dissociated hippocampal neurons were cultured on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips, maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and transfected via calcium phosphate precipitation. The mutant subunits were expressed in organotypic hippocampal slices by injecting AAV9 encoding eGFP-2A-α1T125C or eGFP-2A-α5E125C in the CA1 pyramidal cell body layer. Viral transduction of mouse cerebral cortex was performed by neonatal injection (Figures 3 and 4) or stereotactic injection in adult mice (Figures 5 and 6).

Prior to electrophysiological experiments, the cells or slices were treated with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; 2.5-5 mM, 5-10 min), washed, and then treated with PTL (25-50 μM, 25-45 min) at room temperature to convert the mutant receptors into LiGABARs.

In vivo PTL treatment

For experiments in Figures 5 and 6, we made a craniotomy of 2-3 mm in diameter with subsequent duratomy on anesthetized mice. We applied 100 μl of HEPES-aCSF, which contained PAG-1C (250 μM) and TECP (250-500 μM), onto the exposed cortex for 1 hr. For multi-electrode recordings in awake mice (Figure 8), we thinned the skull and opened a small craniotomy (0.5-1.5 mm in diameter) without duratomy over the visual cortex. The PTL solution was infused into the brain at a rate of 100 nl/min for 10 min with a glass micropipette attached to a microinfusion pump (UMP3 with SYS-Micro4 controller; World Precision Instrument). In control experiments, vehicle solution containing 500 μM TCEP without PAG-1C was infused.

Subcellular LiGABAR Mapping via Two-photon GABA uncaging

Imaging and uncaging were performed using a two-photon laser scanning microscope (MOM; Sutter). The light source for fluorescence excitation (800 nm for Alexa Fluor 594 and 940 nm for gephyrin intrabody) and RuBi-GABA uncaging (800 nm) was a Ti:Sapphire laser (Chameleon XR; Coherent). LiGABAR-expressing hippocampal neurons were voltage-clamped at 0 mV, with 25 μM DNQX, 50 μM D-AP5, and 0.5 μM TTX in the bath. Internal solution included 200 μM Alexa Fluor 594 (Life Technologies) for visualizing dendritic morphology. RuBi-GABA (200-400 μM; Abcam) was added to aCSF and re-circulated using a peristaltic pump (Idex). Uncaging was carried out at designated locations for 5-10 ms with a light intensity of ~150 mW. Full-field 390 nm (1.2 mW/mm2) or 540 nm (3.2 mW/mm2) conditioning flashes (5 sec) from an LED light source (Lumencor) were delivered through the objective. Photoswitching was calculated as 1 - (I540/I390), where I refers to the peak amplitude of GABA-elicited current.

Photo-control of LiGABAR in vivo

Visual stimulus generated with PsychToolbox was either a circular patch of drifting square-wave gratings in full contrast (Figure 6) or a square full contrast checkerboard (Figure 8) against a mean luminance grey background. Targeted loose-patch recordings for Figure 6 were made from PV-tdTOM and LiGABAR-eGFP double positive cells in layer 2/3 (150-350 μm below pia) of the visual cortex, using a two-photon laser-scanning microscope (Sutter) with a Ti:Sapphire laser (1050 nm; Coherent). Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz using a BNC2090 analog-to-digital convertor (National Instrument). For multi-electrode extracellular recordings (Figure 8), a 16-channel probe (A1x16-3mm-25-177-A16; NeuroNexus) was used. Recordings were amplified and digitized at 30 kHz (Spikegadget). MClust was used for off-line sorting of the spike waveforms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Prof. Cynthia Czajkowski (University of Wisconsin, USA), Prof. Robert L. Macdonald (Vanderbilt University, USA), and Dr. Hartmut Luddens (University of Mainz, Germany) for sharing cDNAs of the wild-type GABAA receptors, and Prof. Don Arnold (University of Southern California, USA) for sharing the clone of gephyrin intrabody. We also thank Dr. Mei Li (UC Berkeley) for preparing the viruses and Rachel Montpetit for assistance in molecular biology. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (U01 NS090527, P30 EY003176, and PN2 EY018241 to R.H.K. and 1R01EY023756-01 to H.A.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.H.K., W.-C.L., and M.-C.T. wrote the paper. R.H.K., W.-C.L., M.-C.T., C.M.D., and H.A. designed experiments. W.-C.L., M.-C.T., C.M.D., and C.M.S. performed electrophysiological experiments and analyzed data. W.-C.L. designed and synthesized the compounds. M.-C.T. performed immunohistochemical experiments. M.-C.T. and J.V. performed in vivo experiments and analyzed data. C.M.S. and N.M.W. prepared DNA clones.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures and seven figures and can be found with this article online.

REFERENCES

- Auger C, Kondo S, Marty A. Multivesicular release at single functional synaptic sites in cerebellar stellate and basket cells. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4532–4547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04532.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avermann M, Tomm C, Mateo C, Gerstner W, Petersen CC. Microcircuits of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in layer 2/3 of mouse barrel cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;107:3116–34. doi: 10.1152/jn.00917.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind F, Ledri M, Sørensen AT, Nikitidou L, Melis M, Bielefeld P, Kirik D, Deisseroth K, Andersson M, Kokaia M. Optogenetic inhibition of chemically induced hypersynchronized bursting in mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;65:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann R, Kongsbak K, Sorensen PL, Sander T, Balle T. A unified model of the GABAA receptor comprising agonist and benzodiazepine binding sites. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e52323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman LW, Rosahl TW, Brussaard AB. Neonatal development of the rat visual cortex: synaptic function of GABAA receptor α subunits. J. Physiol. 2002;545:169–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley SG, Revilla V, Cull-Candy SG, Wisden W, Farrant M. Adaptive regulation of neuronal excitability by a voltage-independent potassium conductance. Nature. 2001;409:88–92. doi: 10.1038/35051086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunig I, Scotti E, Sidler C, Fritschy JM. Intact sorting, targeting, and clustering of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes in hippocampal neurons in vitro. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;443:43–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Wang XJ. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35:203–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre MD, Renzi M, Farrant M, Nusser Z. Setting the time course of inhibitory synaptic currents by mixing multiple GABAA receptor α subunit isoforms. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:5853–5867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6495-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of 7 major subunits. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Panzanelli P, Kralic JE, Vogt KE, Sassoe-Pognetto M. Differential dependence of axo-dendritic and axo-somatic GABAergic synapses on GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit in Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3245–3255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Wichmann T. GABAergic circuits in the basal ganglia and movement disorders. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;160:287–312. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier A, Gauron C, Volovitch M, Bensimon D, Jullien L, Vriz S. How to control proteins with light in living systems. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:533–541. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GG, Junge JA, Mora RJ, Kwon HB, Olson CA, Takahashi TT, Liman ER, Ellis-Davies GC, McGee AW, Sabatini BL, et al. Recombinant probes for visualizing endogenous synaptic proteins in living neurons. Neuron. 2013;78:971–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Dong EB, Grayson DR, Veldic M, Zhang XQ, Costa E. GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: new treatment strategies on the horizon. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180:191–205. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub A, Shu Y, Haider B, Kraushaar U, Duque A, McCormick DA. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials carry synchronized frequency information in active cortical networks. Neuron. 2005;47:423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Gan J, Jonas P. Interneurons. Fast-spiking, parvalbumin+ GABAergic interneurons: from cellular design to microcircuit function. Science. 2014;345:1255263. doi: 10.1126/science.1255263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Serra M, Gascon-Moya M, Hirtz JJ, Pittolo S, Poskanzer KE, Ferrer E, Alibes R, Busque F, Yuste R, Hernando J, et al. Two-photon neuronal and astrocytic stimulation with azobenzene-based photoswitches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8693–8701. doi: 10.1021/ja5026326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasugai Y, Swinny JD, Roberts JDB, Dalezios Y, Fukazawa Y, Sieghart W, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P. Quantitative localisation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptor subunits on hippocampal pyramidal cells by freeze-fracture replica immunolabelling. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;32:1868–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzner S, Busse L, Carandini M. GABAA inhibition controls response gain in visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:5931–5941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5753-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Roberts JD, Somogyi P. Cell type- and input-specific differences in the number and subtypes of synaptic GABAA receptors in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2513–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralic JE, Korpi ER, O'Buckley TK, Homanics GE, Morrow AL. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of GABAA receptor α1 subunit knockout mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302:1037–1045. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RH, Mourot A, Adesnik H. Optogenetic pharmacology for control of native neuronal signaling proteins. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nn.3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Ruiz A, Rusakov DA, Scott R, Semyanov A, Walker MC. Presynaptic, extrasynaptic and axonal GABAA receptors in the CNS: where and why? Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2005;87:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit messenger RNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W-C, Davenport CM, Mourot A, Vytla D, Smith CM, Medeiros KA, Chambers JJ, Kramer RH. Engineering a light-regulated GABAA receptor for optical control of neural inhibition. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:1414–1419. doi: 10.1021/cb500167u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Hayama T, Kasai H, Ellis-Davies GCR. Two-photon uncaging of γ-aminobutyric acid in intact brain tissue. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:255–257. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PS, Aricescu AR. Crystal structure of a human GABAA receptor. Nature. 2014;512:270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABAA receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton AJ, Fisher JL. Effect of the α subunit subtype on the macroscopic kinetic properties of recombinant GABAA receptors. Brain Res. 2007;1165:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y, Yim MJ, Swiech L, Kempton HR, Dahlman JE, Parnas O, Eisenhaure TM, Jovanovic M, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell. 2014;159:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev I, Maiya R, Harnett MT, Schafer GL, Ryabinin AE, Blednov YA, Morikawa H, Boehm SL, Homanics GE, Berman A, et al. Transcriptional signatures of cellular plasticity in mice lacking the α1 subunit of GABAA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:5673–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0860-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthi K, Lin YX. The contribution of GABAergic dysfunction to neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2011;17:452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Isacoff EY. Tethered ligands reveal glutamate receptor desensitization depends on subunit occupancy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:273–280. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruano D, Perrais D, Rossier J, Ropert N. Expression of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs by layer V pyramidal cells of the rat primary visual cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:857–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Mohler H. GABAA receptor subtypes: Therapeutic potential in Down syndrome, affective disorders, schizophrenia, and autism. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014;54:483–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman DM. GABAergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:8–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042suppl.3008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit messenger RNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer HU, Wildner H, Yevenes GE. Fast synaptic inhibition in spinal sensory processing and pain control. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92:193–235. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Vierock J, Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Tsunoda S, Kianianmomeni A, Prigge M, Berndt A, Cushman J, Polle J, et al. The microbial opsin family of optogenetic tools. Cell. 2011;147:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.