Abstract

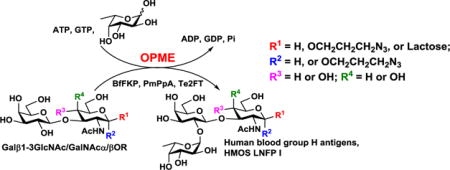

A novel α1–2-fucosyltransferase from Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 (Te2FT) with high fucosyltransferase activity and low donor hydrolysis activity was discovered and characterized. It was used in an efficient one-pot multienzyme (OPME) fucosylation system for high-yield synthesis of human blood group H antigens containing β1–3-linked galactosides and an important human milk oligosaccharide (HMOS) lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP I) in preparative and gram scales. LNFP I was shown to be selectively consumed by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis but not Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis and is a potential prebiotic.

TOC image

Lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP I) and human blood H group antigens were synthesized efficiently by one-pot multienzyme (OPME) fucosylation with a bacterial α1-2-fucosyltransferase.

α1–2-Linked fucose is a major structural component of all human histo-blood group ABH antigens, some Lewis antigens such as Lewis b and Lewis y,1 and many neutral human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS) where they have been found to posses prebiotic, antiadhesive antimicrobial, and immunomodulating activities which contribute significantly to the benefits of breast feeding.2–5

To facilitate enzymatic and chemoenzymatic synthesis of α1–2-fucosides, several bacterial α1–2-fucosyltransferases (2FTs) have been cloned and characterized. These include Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) FutC (HpFutC or Hp2FT),6, 7 Escherichia coli (E. coli) O86:B7 WbwK,8 E. coli O86:K62:H2 WbnK,9 E. coli O128 WbsJ,10–12 and E. coli O127:K63(B8) WbiQ.13 However, their expression levels are usually low which limit their application in synthesis. A more recently characterized E. coli O126 WbgL14, 15 has a reasonable expression level but has a preference towards β1–4-linked galactosides as acceptor substrates. The access to α1–2-fucosylated β1–3-linked galactosides in large scales has been greatly hampered by the lack of a 2FT that has a high activity and can be obtained in large amounts. Here we report a novel α1–2-fucosyltransferase (encoded by gene tll0994) from thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-116 (Te2FT). It has a high expression level in E. coli and a high specific activity. It is a powerful catalyst for highly efficient enzymatic synthesis of α1–2-fucosylated β1–3-linked galactosides in preparative and large scales.

Te2FT shows 27–33% identities and 44–48% similarities to previously reported bacterial α1–2-fucosyltransferases and belongs to Carbohydrate Active enZyme (CAZy)17, 18 glycosyltransferase family 11 (GT11) (Fig. S1). Te2FT was cloned as an N-His6-tagged recombinant protein (His6-Te2FT) in pET15b vector, as well as an N-maltose binding protein (MBP)-fused and C-His6-tagged recombinant protein (MBP-Te2FT-His6) in pMAL-c4X vector. Ni2+-column purified proteins have molecular weights close to the calculated values of 36.2 KDa (His6-Te2FT) and 75.8 KDa (MBP-Te2FT-His6), respectively (Fig. S2). When expressed under optimal conditions at 16 °C for 20 hours with shaking at 120 rpm, the expression levels of His6-Te2FT and MBP-Te2FT-His6 were 15 and 16 mg per liter E. coli culture (the amounts of purified proteins determined by bicinchoninic acid assays), respectively. The expression level of His6-Te2FT (15 mg/L culture) was significantly higher than other reported α1–2FTs14 and was comparable to recombinant C-truncated Helicobacter pylori α3FT19 which, partially due to its easy accessibility by recombinant expression, has been crystallized20 and broadly used in enzymatic and chemoenzymatic synthesis of α1–3-linked fucosides.21–24 Due to its good expression level and lower molecular weight compared to MBP-Te2FT-His6, His6-Te2FT was used further for detailed characterization and synthesis.

Initial substrate specificity studies using various disaccharides as acceptor substrates indicated that His6-Te2FT worked well with type I (Galβ1–3GlcNAcβOR) and its derivative (Galβ1–3GlcNAcαOR), Type III (Galβ1–3GalNAcαOR), and type IV (Galβ1–3GalNAcβOR) acceptors for adding a fucose α1–2-linked to the terminal galactose (Gal) residue. However, type II (Galβ1–4GlcNAcβOR) and type V (Galβ1–4GlcβOR)25, 26 glycans were not good acceptors.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-based pH profile study using Galβ1–3GlcNAcβ2AA (a type I glycan with a fluorescent 2-anthranilic acid aglycone) as an acceptor showed that His6-Te2FT was active in a broad pH range of 4.0–10.0 with optimal activities at pH 4.5–6.0 (Fig. S3). About 85% of the optimal activity was found at pH 6.5 under the experimental conditions used. As significant guanosine 5′-diphosphate-fucose (GDP-fucose, the donor substrate for fucosyltransferases) hydrolysis activity of fucosyltransferases could lower synthetic yields,27 the donor hydrolysis activity assays of His6-Te2FT were carried out. To our delight, using 15-fold more enzyme and 3-fold longer reaction time than those in the α1–2-fucosyltransferase activity assays indicated that the donor hydrolysis activity of His6-Te2FT was minimum in the pH range (5.0–8.0) that would normally be used for the α1–2-fucosyltransfer reactions. An optimal pH at 9.5 was observed for the GDP-fucose hydrolysis activity.

A divalent metal ion was not required for the α1–2-fucosyltransferase activity of His6-Te2FT. Adding 10 mM of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) decreased its activity only slightly (Fig. S4). However, its activity was enhanced by about two-fold when 5–20 mM of Mg2+ or Mn2+ was added. The addition of 10 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT) decreased His6-Te2FT activity moderately, indicating disulfide bond formation was not essential for the enzyme activity despite of the presence of 5 cysteine residues in the Te2FT protein sequence.

Since His6-Te2FT was originated from a thermophilic cyanobacterium, its temperature profile was investigated. It was active in a broad temperature range of 25–60 °C with optimal activities observed in the range of 30–45 °C (Fig. S5). Low activity was observed at 15 °C and 20 °C and minimal activity was retained at 65 °C or 70 °C. His6-Te2FT could survive freeze-dry treatment (Fig. S6), indicating its potential for long term storage.

Kinetics studies of His6-Te2FT using Galβ1–3GlcNAcβ2AA as an acceptor (Table 1) indicated its superior α1–2-fucosyltransferase activity. Compared to GST-WbsJ,11, 12 His6Prop-WgbL,14 and Hp2FT,7 His6-Te2FT showed a significantly higher kcat value for GDP-fucose (201-, 6.7-, and 14.6-fold, respectively) and a higher affinity for the acceptor. The catalytic efficiency of His6-Te2FT was similar to that of Hp2FT but is superior to WbsJ and WbgL as reflected by a higher kcat/KM value for GDP-Fuc (29.2-fold and 2.5-fold higher). The GDP-fucose (donor) hydrolysis activity (kcat/KM = 0.54 min−1 mM−1) of His6-Te2FT was 47-fold weaker than its α1–2-fucosyltransferase activity and much lower than the donor hydrolysis activity of Hp2FT (6.07 min−1 mM−1).7 These data indicate that His6-Te2FT is a superior catalyst for enzymatic synthesis of α1–2-linked fucosides.

Table 1.

Apparent kinetic parameters of His6-Te2FT.

| Activity | Substrate | kcat (min−1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (min−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2FT | Galβ1–3GlcNAcβ2AA | 20.0±0.7 | 0.79±0.11 | 25.3 |

| GDP-fucose | 26.3±0.8 | 0.73±0.08 | 36.1 | |

| GDP-Fuc hydrolysis | GDP-fucose | 0.30±0.06 | 0.56±0.21 | 0.54 |

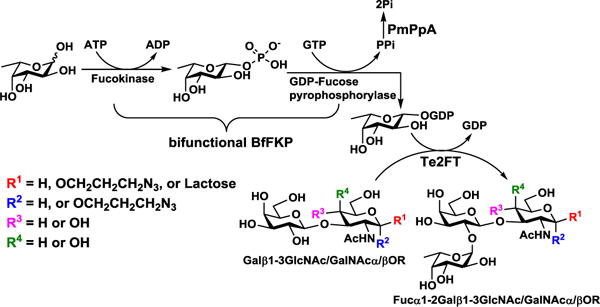

The synthetic application of Te2FT was explored in an efficient one-pot three-enzyme (OP3E) fucosylation system (Scheme 1) for synthesizing various α1–2-linked fucosides. In this system, recombinant bifunctional L-fucokinase/GDP-fucose pyrophosphorylase from Bacteroides fragilis strain NCTC9343 (BfFKP)28 was used for catalyzing the formation of GDP-fucose from fucose, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), and guanidine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) to provide the donor substrate for Te2FT. Pasteurella multocida inorganic pyrophosphatase (PmPpA)29 was used to break down the pyrophosphate by-product to shift the reaction towards the formation of GDP-fucose. As shown in Table 2, the OP3E fucosylation of β1–3-linked galactosides was successfully accomplished with 96%, 95%, 95%, and 98% yields, respectively, to produce desired Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GlcNAcβProN3 (1, a type I H antigen), Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GlcNAcαProN3 (2, a type I H antigen derivative), Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GalNAcαProN3 (3, a type III H antigen), and Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GalNAcβProN3 (4, a type IV H antigen). Moreover, a human milk tetrasaccharide lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) Galβ1–3GlcNAcβ1–3Galβ1–4Glc was also an excellent acceptor for His6-Te2FT and the OP3E synthesis of Fucα1–2LNT (5), a human milk pentasaccharide also known as lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP I), was achieved in a preparative scale (68.1 mg) with an excellent 94% yield.

Scheme 1.

One-pot three-enzyme (OP3E) synthesis of α1–2-fucosides. Enzymes and abbreviations: BfFKP, Bacteroides fragilis strain NCTC9343 bifunctional L-fucokinase/GDP-fucose pyrophosphorylase;28 PmPpA, Pasteurella multocida inorganic pyrophosphorylase;29 and Te2FT, Thermosynechococcus elongatus α1–2-fucosyltransferase.

Table 2.

One-pot three-enzyme (OP3E) synthesis of α1–2-linked fucosides.

| Acceptor | Product | Yield (%) | Amount (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galβ1–3GlcNAcβProN3 | Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GlcNAcβProN3 (1) | 96 | 50.5 |

| Galβ1–3GlcNAcαProN3 | Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GlcNAcαProN3 (2) | 95 | 51.3 |

| Galβ1–3GalNAcαProN3 | Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GalNAcαProN3 (3) | 95 | 35.7 |

| Galβ1–3GalNAcβProN3 | Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GalNAcβProN3 (4) | 98 | 43.8 |

| LNT | Fucα1–2LNT or LNFP I (5) | 94 | 68.1 |

| 95 | 1,146 |

To demonstrate the efficiency of the OP3E fucosylation system and the activity of Te2FT, gram-scale synthesis of Fucα1–2LNT (LNFP I) pentasaccharide was carried out. Pure LNFP I in an amount of 1.146 gram was successfully obtained with an excellent 95% yield. It should be noted that the purification of the product in the gram-scale synthesis of LNFP I was greatly simplified by using activated charcoal which was very efficient in removing nucleotides in the reaction mixtures. Due to the complete consumption of the acceptor LNT in the reaction mixture, separating the pentasaccharide product from other components with smaller molecular weights was conveniently done by a gel filtration column which served similarly as desalting.

The facile synthesis of lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP I) is significant. LNFP I was identified in 1956 as one of the HMOS structures.30 It is missing in the milk of Lea+b− non-secretors,31 otherwisely it is an abundant HMOS species (1.2–1.7 g/liter) in pooled human milk.4 It is not presented in the milk or the colostrum of cows,32, 33 pigs,34 or other domestic animals.33 Therefore it is not readily accessible from natural sources by purification. Chemical synthesis of LNFP I with a β-linked pentanylamino aglycon from a protected tetrasaccharide precursor obtained by a one-pot chemical synthetic procedure was achieved in four steps with 49% yield.35 LNFP I was also synthesized from LNT and GDP-fucose using a recombinant human FUT1 expressed in a baculovirus system (3.0 mg, 71% yield)36 and in whole-cell recombinant E. coli expressing HpFutC (59.4 mg).37 The OP3E system presented here is a more efficient and an economically feasible approach for large-scale production of LNFP I.

Obtaining large amounts of LNFP I by highly efficient OP3E enzymatic process presented here allows downstream investigation of its potential prebiotic application.

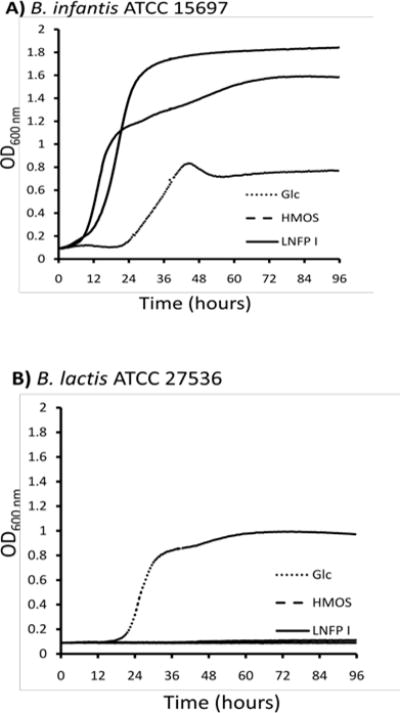

The ability of LNFP I in serving as the sole carbon source for the growth of bifidobacteria was examined. Media containing HMOS (a mixture of oligosaccharides isolated from human milk)38 or glucose were used as controls. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis (B. infantis) ATCC 15697 grew well on LNFP I and HMOS with a similar pattern which was remarkably faster than its growth on glucose (Fig. 1A). To establish specificity, LNFP I was tested for its ability to support the growth of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis (B. lactis) ATCC 27536, a subspecies that did not grow on HMOS.39 B. lactis failed to grow on either LNFP I or HMOS, while it showed a similar growth pattern to B. infantis in the presence of glucose (Fig. 1B). Selective growth of B. infantis on a specific fucosylated HMOS species like LNFP I provides a molecular rationale for the unique enrichment of B. infantis and other infant-borne bifidobacteria in the nursing infant gastrointestinal tract by breastfeeding.40, 41

Fig. 1.

Growth of bifidobacterial strains B. infantis (A) and B. lactis (B) on mMRS medium supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) glucose (Glc, dotted line), human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS, dashed line) or LNFP I (solid line).

In conclusion, Te2FT with a good recombinant expression level and high activity is an important tool for large-scale enzymatic synthesis of various biologically important α1–2-fucosides. We demonstrated again that the one-pot multienzyme (OPME) fucosylation is a highly effective system for chemoenzymatic and enzymatic synthesis of fucosides. The gram-scale synthesis of fucosylated human milk oligosaccharide LNFP I allowed the performance of bacteria growth study which showed that LNFP I was selectively consumed as a carbon source by B. infantis but not B. lactis. Therefore, LNFP I is a potential prebiotic candidate for further development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01HD065122 (to X.C.), FAFU grants XJQ201417 and 612014043 (to C.Z. and B.L.), Scholarships of Education Department of Fujian Province (to C.Z. and Y.W.), and Scholarships of China (to J.Z.). Bruker Avance-800 NMR spectrometer was funded by NSF grant DBIO-722538. H.Y., Y.L., and X.C. are co-founders of Glycohub, Inc., a company focused on the development of carbohydrate-based reagents, diagnostics, and therapeutics. D.A.M. is a co-founder of Evolve Biosystems, a company focused on diet-based manipulation of the gut microbiota. Glycohub, Inc. and Evolve Biosystems played no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details for cloning and characterization of Te2FT, chemical and enzymatic synthesis, NMR and HRMS data, NMR spectra, and bacterial growth study procedures. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Becker DJ, Lowe JB. Glycobiology. 2003;13:41R–53R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newburg DS, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:37–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X. In: Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Baker DC, Horton D, editors. Vol. 72. Academic Press, ACCB; UK: 2015. pp. 113–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunz C, Rudloff S, Baier W, Klein N, Strobel S. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:699–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smilowitz JT, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB, Freeman SL. Annu Rev Nutr. 2014;34:143–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang G, Rasko DA, Sherburne R, Taylor DE. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein DB, Lin YN, Lin CH. Adv Synth & Catal. 2008;350:2313–2321. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo H, Yi W, Shao J, Lu Y, Zhang W, Song J, Wang PG. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7995–8001. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7995-8001.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yi W, Shao J, Zhu L, Li M, Singh M, Lu Y, Lin S, Li H, Ryu K, Shen J, Guo H, Yao Q, Bush CA, Wang PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2040–2041. doi: 10.1021/ja045021y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shao J, Li M, Jia Q, Lu Y, Wang PG. FEBS Lett. 2003;553:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00980-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, Shen J, Liu X, Shao J, Yi W, Chow CS, Wang PG. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11590–11597. doi: 10.1021/bi801067s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Liu XW, Shao J, Shen J, Jia Q, Yi W, Song JK, Woodward R, Chow CS, Wang PG. Biochemistry. 2008;47:378–387. doi: 10.1021/bi701345v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettit N, Styslinger T, Mei Z, Han W, Zhao G, Wang PG. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engels L, Elling L. Glycobiology. 2014;24:170–178. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, DebRoy C, Fratamico P. Mol Cell Probes. 2007;21:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura Y, Kaneko T, Sato S, Ikeuchi M, Katoh H, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Iriguchi M, Kawashima K, Kimura T, Kishida Y, Kiyokawa C, Kohara M, Matsumoto M, Matsuno A, Nakazaki N, Shimpo S, Sugimoto M, Takeuchi C, Yamada M, Tabata S. DNA Res. 2002;9:123–130. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.4.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell JA, Davies GJ, Bulone V, Henrissat B. Biochem J. 1997;326(Pt 3):929–939. doi: 10.1042/bj3260929u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin SW, Yuan TM, Li JR, Lin CH. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8108–8116. doi: 10.1021/bi0601297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun HY, Lin SW, Ko TP, Pan JF, Liu CL, Lin CN, Wang AH, Lin CH. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9973–9982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Hu T, Frantom PA, Zheng T, Gerwe B, Del Amo DS, Garret S, Seidel RD, 3rd, Wu P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16096–16101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908248106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, Lau K, Li Y, Sugiarto G, Chen X. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2012;4:233–247. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch110277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiarto G, Lau K, Qu J, Li Y, Lim S, Mu S, Ames JB, Fisher AJ, Chen X. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1232–1240. doi: 10.1021/cb300125k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiarto G, Lau K, Yu H, Vuong S, Thon V, Li Y, Huang S, Chen X. Glycobiology. 2011;21:387–396. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakomori S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:247–266. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Letts JA, Rose NL, Fang YR, Barry CH, Borisova SN, Seto NO, Palcic MM, Evans SV. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3625–3632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507620200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Lau K, Cheng J, Yu H, Li Y, Sugiarto G, Huang S, Ding L, Thon V, Wang PG, Chen X. Glycobiology. 2010;20:1077–1088. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi W, Liu X, Li Y, Li J, Xia C, Zhou G, Zhang W, Zhao W, Chen X, Wang PG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4207–4212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau K, Thon V, Yu H, Ding L, Chen Y, Muthana MM, Wong D, Huang R, Chen X. Chem Commun. 2010;46:6066–6068. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01381a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn R, Baer HH, Gauhe A. Chem Ber. 1956;89:2514–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobata A, Ginsburg V, Tsuda M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;130:509–513. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldredge DL, Geronimo MR, Hua S, Nwosu CC, Lebrilla CB, Barile D. Glycobiology. 2013;23:664–676. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao N, DePeters EJ, Freeman S, German JB, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:3768–3778. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao N, Ochonicky KL, German JB, Donovan SM, Lebrilla CB. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:4653–4659. doi: 10.1021/jf100398u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu Y, Lu XA, Zulueta MM, Tsai CM, Lin KI, Hung SC, Wong CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4549–4552. doi: 10.1021/ja300284x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyazaki T, Sato T, Furukawa K, Ajisaka K. Methods Enzymol. 2010;480:511–524. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumgartner F, Jurzitza L, Conrad J, Beifuss U, Sprenger GA, Albermann C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:6799–6806. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LoCascio RG, Ninonuevo MR, Freeman SL, Sela DA, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:8914–8919. doi: 10.1021/jf0710480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Underwood MA, Kalanetra KM, Bokulich NA, Lewis ZT, Mirmiran M, Tancredi DJ, Mills DA. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1585–1591 e1589. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis ZT, Totten SM, Smilowitz JT, Popovic M, Parker E, Lemay DG, Van Tassell ML, Miller MJ, Jin YS, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. Microbiome. 2015;3:13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0071-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huda MN, Lewis Z, Kalanetra KM, Rashid M, Ahmad SM, Raqib R, Qadri F, Underwood MA, Mills DA, Stephensen CB. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e362–372. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.