Abstract

Objectives

To assess whether exposure to alcohol use in films (AUF) is associated with alcohol use susceptibility, current alcohol use, and binge drinking in adolescents from two Latin American countries.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with 13,295 middle school students from public and private schools in Mexico and Argentina. Exposure to alcohol use in over 400 contemporary top box office films in each country was estimated using previously validated methods. Outcome measures included current drinking (i.e., any drink in the last 30 days), ever binge-drinking (i.e., more than 4 or 5 drinks in a row for females and males, respectively) and, among never drinkers, alcohol susceptibility (i.e., might drink in the next year or accept a drink from a friend). Multivariate models were adjusted for age, sex, parental education, peer drinking, sensation seeking, parenting style and media access.

Results

Mean age was 12.5 years (SD = 0.7) and the prevalence of alcohol consumption and binge drinking was 19.8% and 10.9% respectively. Mean exposure to alcohol from the film sample was about 7 hours in both countries. Adjusted models indicated independent dose-response associations between higher levels of exposure to AUF and all outcomes; the adjusted odds ratios (OR) comparing quartiles 4 and 1 1.99 (95% CI 1.73 - 2.30) for current drinking, 1.68 (1.39 - 2.02) for binge drinking, and 1.80 (1.52 - 2.12) for alcohol susceptibility. Compared to Mexican adolescents, Argentine adolescents were significantly more likely to have engaged in binge drinking (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.12 - 1.76.) and, among never drinkers, were more susceptible to trying drinking (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.20 - 1.64).

Conclusions

Higher levels of exposure to alcohol use in films was associated with higher likelihood of alcohol use, binge drinking, and alcohol susceptibility in Latin American adolescents.

Keywords: Alcohol, movies, adolescents, Latin America, motion pictures

Alcohol-related health and social problems are prevalent in almost all societies that consume alcohol (Rehm et al., 2009). Alcohol use is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality worldwide, causing 3.3 million deaths each year (World Health Organization, 2014). Initiation of alcohol use during early adolescence is an important predictor of alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes (Hingson et al., 2002), suicide, neurocognitive impairment (Squeglia et al., 2009), and alcohol dependence/abuse at later ages (Grant and Dawson, 1998). Furthermore, early use of alcohol and binge drinking are common among Latin American adolescents. In 2014, approximately 70% of Argentine adolescents aged 13 to 17 years had ever consumed alcohol, with a lower prevalence in Mexico (42.9%) (Medina-Mora ME et al., 2012). Prevalence in these countries is similar to other Latin American countries (Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito (ONUDD), 2010) showing that underage drinking is an important public health problem in this region.

Previous studies have identified numerous factors that influence the risk of alcohol use among adolescents, including parents and peers (Bahr et al., 2005, Callas et al., 2004), school and work (Staff et al., 2010), socioeconomic status (Lemstra et al., 2008), other drug use (Everett et al., 1998), risk taking and sensation seeking (Stoolmiller et al., 2010, Hull et al., 2014), and drinking attitudes (Keyes et al., 2012), among others (Patrick and Schulenberg, 2013). Media and marketing represent another set of risk factors (Gordon et al., 2010, Anderson et al., 2009). Alcohol advertising, such as direct advertising on television, movie theaters, and magazines has been associated with increased adolescent drinking (Morgenstern et al., 2011a, Anderson et al., 2009), and distribution of alcohol branded merchandise is associated with future alcohol use (McClure et al., 2006). Experimental studies have shown that alcohol portrayals in films directly influence actual alcohol intake, presumably by imitation and cue-reactivity processes (Engels et al., 2009, Koordeman et al., 2011). Finally, cross-sectional and longitudinal associations have been reported for the relationship between exposure to alcohol use in films (AUF) and alcohol use and binge drinking among adolescents in the United States, England and Germany (Hanewinkel and Sargent, 2009, Hanewinkel et al., 2014, Hanewinkel et al., 2012, Sargent et al., 2006, Hanewinkel et al., 2007, Waylen et al., 2015, Dal Cin et al., 2009, Morgenstern et al., 2011a, Morgenstern et al., 2011b, Morgenstern et al., 2014, Nunez-Smith et al., 2010). That alcohol companies pay for alcohol brand placement in films is important, because it means that film alcohol depictions could be reduced if payments were restricted, as was the case with smoking in films (Bergamini et al., 2013).

The studies mentioned above have been conducted in high income European countries and in the United States. We were unable to find studies assessing the relationship between film exposure to alcohol and alcohol use among Latin-American adolescents. In Latin American countries, like in most Western nations, film exposure to alcohol for adolescents comes primarily from Hollywood films (Thrasher et al., 2014). However, Latin-American adolescents may not have the same level of viewership or exposure. Furthermore, they may not react to the exposure the same way adolescents do in other Western countries. For example, studies of US adolescents show stronger associations between exposure to film smoking portrayals and adolescent smoking behavior among white (Soneji et al., 2012) compared to Black adolescents (Tanski et al., 2012). Black adolescents appear responsive to film smoking, but only to smoking by Black actors or films oriented towards Black cultural demographics (Dal Cin et al., 2013). Similarly, the lack of cultural congruence between film characters and Latin American adolescents may dampen film social influence effects. Therefore, we conducted this study to examine exposure of Latin American adolescents to AUF and its association with alcohol use.

Methods

Study sample and procedure

The study was conducted among students in Argentina and Mexico middle schools. In Argentina, during May and June 2014, a convenience sample of 33 schools from three large cities (Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Tucumán) participated in the study (n=15, 8, 10, respectively), with public schools identified by the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education (n=18) and private schools identified through personal contacts (n=15). In Mexico, in February and March 2015 60 public middle schools were selected using a stratified random sampling design in Mexico's three largest cities (Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey). Sampling strata were based on: a) high and low levels of socioeconomic marginalization using 2010 census data for the census tracts where schools were located (Consejo Nacional de Población, 2010) b) city-specific tertiles of retail establishment density in school census tracts (another study aim involved the association between retail tobacco density and adolescent smoking). Within each of these six strata, three or four schools were randomly selected with selection probability proportional to the number of students in each school and a quota of 20 schools per city. When a school did not agree to participate, a replacement school was selected randomly from the same stratum.

Passive consent was requested from parents or caretakers, and students signed an active consent form. Study protocols were approved by NIH-certified human subjects research boards in Argentina (i.e., Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas) and Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública).

Development of Questionnaire Measures

The aim of the survey was to assess media/marketing exposures and their association with adolescent risk behaviors. The questionnaire included items used in surveys for adolescents previously implemented in Argentina, Mexico, and in the US (Alderete et al., 2009, Dal Cin et al., 2008a, Sargent, 2005, Thrasher et al., 2008). Items in English were translated and reviewed by Spanish-speaking research staff, and the final survey instrument was pilot tested with students both countries to ensure adequate understanding of questions, instructions and confidentiality statements.

The self-administered questionnaires were completed in the classroom under the supervision of trained research staff. Surveys included questions about attitudes that predict the onset of alcohol use, alcohol use, exposure to AUF and pertinent covariates.

Assessment of alcohol attitudes and behavior

Alcohol susceptibility was measured among those who never drank, using items that captured future intent to drink during the next year and resistance to peer offers, with four response options ranging from “definitively yes” to “definitively no”. The susceptibility construct has been validated as a predictor of smoking onset in longitudinal studies of adolescents, and also predicts the onset of drinking in longitudinal studies of adolescents (McClure et al., 2009). To be consistent with how the measure is coded for smoking (Pierce et al., 1996), participants who stated “definitely not” to both questions were coded as “nonsusceptible never-drinkers”, the rest being coded as “susceptible never-drinkers”. A respondent was considered to be a current drinker if he or she reported any number greater than zero to the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink alcohol?” We assessed binge drinking by asking if he or she had ever drunk more than 4 or 5 drinks in a row, with the quantity used depending on gender of the student (Courtney and Polich, 2009).

Exposure to alcohol measurement

Films chosen for this study included films released in Argentina between 2009 and 2013 and listed by the Argentinean National Institute of Cinema and Visual Arts (INCAA) amongst the top 100 revenue-grossing films for the year released. The top 100 films for Mexico were listed by the Mexican Institute of Cinematography (IMCINE), for the years from 2010 to 2014, because data collection took place one year after Argentina. To estimate exposure to AUF, we used methods validated for measuring exposure to film smoking by the Dartmouth Media Research Laboratory (DMRL) (Bergamini et al., 2013, Dalton et al., 2002).

Adolescents’ exposure to films was assessed by randomly selecting 50 film titles for each participant from the total film sample, with participants indicating which films they had seen. Thus, each adolescent questionnaire contained a unique sub-sample of film titles (Sargent et al., 2008). For each film, depictions of alcohol were timed when there was real or implied use of an alcoholic beverage by one or more characters, including purchases and occasions when alcoholic beverages were clearly in the possession of a character. All alcohol use and implied use was timed in seconds from the moment the alcohol appeared on screen. Empty alcoholic beverage containers and those displayed but not implied as being consumed were not timed as alcohol use. To evaluate inter-rater reliability for the US films, a random sample of 10% of films was coded by two coders yielding kappa of 0.76 for alcohol time depictions. These statistics represent the overall reliability for all films coded by the DMRL. Due to the smaller sample size of Mexican and Argentine films, 20% were double coded, yielding Cohen's kappa's of 0.74 in Mexico; and 0.76 in Argentina.

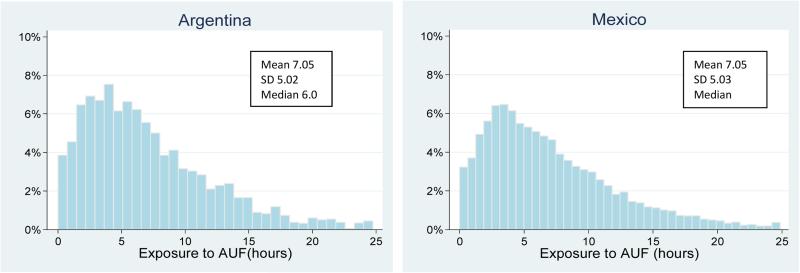

Film alcohol exposure was determined by: 1. summing the seconds of alcohol exposure across all films the adolescent reported having seen; 2.dividing seconds of alcohol use seen by the total seconds of film alcohol exposure across all 50 films in the participantś unique list; 3. multiplying the proportion in step 2 by the total seconds of alcohol use across the full list of films for that country. Exposure to film alcohol use consisted of a continuous variable, scaled in hours of exposure for Figure 1, then scaled as a standardized score (as described below) for Figure 2, then classified into quartiles, based on the distribution in each country for use in logistic regression.

Figure 1.

Distributions for the estimated exposure to alcohol use in films in Argentina and Mexico

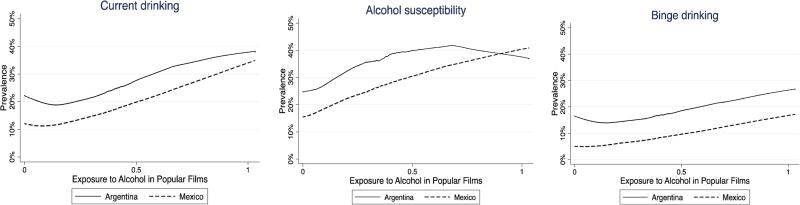

Figure 2.

Crude association between exposure to alcohol in popular films and alcohol use susceptibility, current alcohol use, and binge drinking.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, parents’ years of formal education (<=7, 8-12, >12 or unknown), parenting style, access to media, peer friend drinking and sensation seeking (Sargent et al., 2010). Parent drinking was not assessed because it was considered a sensitive question by school personnel, and furthermore has not been found to be particularly influential in our prior studies of media use and drinking behaviors (Stoolmiller et al., 2012).

Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were conducted with Stata version v13 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Local scatterplot smoothing was used to graphically represent the crude relationship between exposure to AUF and alcohol use, binge drinking and alcohol susceptibility among never drinkers for each country. To compare the dose-response curves, we standardized exposure to AUF for each country so that the lowest value was 0 and the highest was 1 after recoding outliers in the 95th percentile that otherwise substantially skewed the exposure distribution.

Univariate linear regression models were used to compare continuous variables and logistic regression models to compare categorical variables, between countries, in both models random intercepts for schools were used. Multilevel logistic regression models (with random intercepts for school) were used to assess the relationship between exposure to AUF (comparing lowest with higher quartiles of exposure) and current drinking, binge drinking and alcohol susceptibility among never drinkers. All models included the covariates listed above. Age and indexed variables (sensation seeking, parenting style, media access) were entered as continuous variables. Adjusted ORs were estimated across country-specific quartiles of AUF exposure with quartile 1 as the referent category. We also tested for an AUF-country interaction.

Multilevel logistic regression models using exposure to AUF as a continuous variable instead of quartiles were also estimated separately in a sensitivity analysis. For this, we entered exposure to AUF measured in hours of exposure. The findings were similar in direction and statistical significance for both types of variables.

Results

Description of the film samples

The Argentina analytic film sample (2009-2013) had 427 films, of which 47 were produced in Argentina and 380 in the US; the whole sample depicted 24.74 hours of alcohol use. The Mexican analytic sample of films (2010-2014) contained 446 films, 46 of which were produced in Mexico and 400 in the US; that sample depicted 24.85 hours of alcohol use.

Description of the population samples

Of all eligible students in Argentina (n=3826), 1.3% had parents who refused participation, 4.5% declined participation, and 11% were absent the day of the survey, for a final sample of 3172 students (Buenos Aires n=1664; Córdoba n=983; Tucumán n=525). In Mexico the school participation rate was 92% (60 of 65 invited). Of eligible students in Mexico, 5% of parents declined permission, 0.02% of students refused to participate, and 11% students were absent the day of the survey, for a final sample of 10,123 students (Mexico City n=3486, Guadalajara n=3461 and Monterrey n=3176). The overall mean age of participants was 12.5 years (SD = 0.72), 51.9% were male; other characteristics are described in Table 1. The prevalence of current drinking in the total sample was 19.8%; among never drinkers 28.5% were susceptible to drinking, and the prevalence of binge drinking was 10.9%. There were many statistically significant differences between the Argentinean and Mexican samples. In Argentina, more boys participated than in Mexico (57.6% and 50.1%, respectively, p = 0.032), and students from Argentina were approximately four months older, and their parents had more education and tended to have a more authoritative parenting style compared to Mexican students (p = 0.002); means for sensation were significantly higher among Argentinean adolescents. Alcohol consumption was also higher among Argentine than Mexican students (25.4% vs. 18.1%, respectively; p=0.003).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Variable | Argentina | Mexico | Overall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | P* | n (%) | ||

| 3,172 (100) | 10,123 (100) | 13,295 (100) | |||

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1335 (42.4) | 5041 (49.9) | 0.032 | 6376 (48.2) | |

| Male | 1817 (57.6) | 5049 (50.1) | 6866 (51.9) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 12.83 (0.95) | 12.43 (0.60) | 0.002 | 12.53 (0.72) | |

| Parent's education | 0.012 | ||||

| ≤7 years | 214 (6.9) | 1317 (13.1) | 1531 (11.7) | ||

| 8-12 years | 1289 (41.4) | 6279 (62.6) | 7568 (57.6) | ||

| >12 years | 1292 (41.5) | 1573 (15.7) | 2865 (21.8) | ||

| Don't know | 322 (10.3) | 858 (8.6) | 1180 (9.0) | ||

| Personal characteristics | |||||

| Sensation seeking, mean (SD), range 1-5 | 3.21 (1.06) | 2.88 (1.05) | 0.001 | ||

| Parenting style, mean (SD), range 1-5 | 3.98 (0.67) | 3.86 (0.88) | 0.014 | ||

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Never drinker | 1504 (47.7) | 5392 (54.0) | 0.02 | 6896 (52.5) | |

| Susceptible to drinking alcohol | 529 (35.2) | 1433 (26.6) | 0.001 | 1962 (28.5) | |

| Ever drinker | 1650(52.3) | 4595 (46.0) | 6630 (50.4) | ||

| Current drinker | 801 (25.4) | 1822 (18.1) | 0.003 | 2850 (19.8) | |

| Binge drinking | 554 (17.6) | 884 ( 8.8) | 0.001 | 1424 (10.9) | |

| Friend who drink | 1664 (52.8 ) | 3903 (38.8) | 0.001 | 5567 (42.2) | |

Univariate linear regression models were used to compare continuous variables and logistic regression models to compare categorical variables, in both models random intercepts for schools were used

Exposure to AUF and its crude association with drinking

The median estimated exposure to AUF was 6.0 hours in adolescents from Argentina and 5.9 hours in those from Mexico. Figure 1 shows the distributions for the estimated exposure to alcohol use in films. Both histograms were positively skewed, with some adolescents having exposures that ranged upwards of 15 hours.

Figure 2 shows the unadjusted association between a standardized measure of exposure to AUF and current drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol susceptibility for adolescents of both countries. For the most part, the curves show a dose–response association between exposure to film alcohol depictions and prevalence of the three outcomes studied. Any deviation from a linear dose-response is restricted to adolescents with very high exposure, as has been described in past studies of film smoking (Sargent et al., 2008).

Multivariate analysis

Table 2 shows that in both countries, and after controlling by age, sex, parental education, friends who drink, sensation seeking, parenting style and media access, adolescents with higher exposure to AUF were significantly more likely to be current drinkers (OR quartile 4 vs quartile 1= 1.99, 95% CI 1.73 - 2.30), to have engaged in binge drinking (ORq4 vs q1 = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.39 - 2.02), and to have a drink during the next year (ORq4 vs q1 = 1.80, 95% CI:1.52 - 2.12). The ORs comparing quartiles 2 and 3 with quartile 1 were also (with one exception) statistically significant, with increasing odds ratios across quartiles that mirrored the linear dose-response relation illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Multilevel logistic regressions

| Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Current drinker | Binge drinking | Alcohol susceptibility |

| Movie alcohol exposure | |||

| Quartile 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Quartile 2 | 1.13 | 1.23* | 1.39*** |

| (0.97 - 1.32) | (1.00 - 1.49) | (1.18 - 1.62) | |

| Quartile 3 | 1.35*** | 1.24* | 1.60*** |

| (1.16 - 1.56) | (1.02 - 1.50) | (1.36 - 1.88) | |

| Quartile 4 | 1.99*** | 1.68*** | 1.80*** |

| (1.72 - 2.29) | (1.39 - 2.01) | (1.53 - 2.13) | |

| Country | |||

| Mexico | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Argentina | 1.10 | 1.40** | 1.40*** |

| (0.91 - 1.32) | (1.11 - 1.76) | (1.19 - 1.63) | |

Odds ratios adjusted for age, sex, parent education, friend drinking, sensation seeking, parenting style and media access.

To determine whether the relationship between exposure to AUF and alcohol use varied by country, interactions between quartiles of exposure to AUF and country were also examined. No significant interaction was detected for any outcome (p>0.05). Adolescents from Argentina tended to be more likely engage in binge drinking (OR =1.40; 95% CI 1.12 - 1.76) and to be more susceptible to drink in the next year (OR = 1.40; 95% CI 1.20 - 1.64) in comparison with Mexican youth independent of the exposure to AUF.

Discussion

Our study is the first to confirm the association between AUF and drinking behavior in adolescents from Latin America. Our results are consistent with studies conducted in other countries (Hanewinkel and Sargent, 2009, Hanewinkel et al., 2012, Hanewinkel et al., 2007, Sargent et al., 2006, Waylen et al., 2015, Wills et al., 2009). Although our study suggested different mean levels of exposure to AUF in Argentina and Mexico than for adolescents from the United States (Median 8.6 hours) (Sargent et al., 2006), or Germany (Median 3.4 hours) (Hanewinkel et al., 2007) we found a similar dose-response association between exposure to AUF and alcohol use, engagement in binge drinking and alcohol susceptibility.

Some authors suggest that it is difficult to attribute substance use to film depictions of the substance (Chapman and Farrelly, 2011) because youth at risk for alcohol consumption may self-select to watch films that contain more alcohol portrayals than youth who are not at risk. These associations were independent of many potential confounders that included peer drinking, sensation seeking, and other risk factors that could promote both higher alcohol use and higher likelihood to seek out films with drinking. The fact that the association between exposure to AUF and drinking persists after adjusting for covariates that are plausible confounders of media exposure effects, including sensation seeking (Stoolmiller et al., 2010), access to media(Hanewinkel et al., 2008), and parenting styles supports the idea that exposure to AUF is an independent social risk factor.

This study has several limitations which should be acknowledged. First, data on exposure to AUF and alcohol use were all cross-sectional; therefore, we cannot provide information on the temporal sequence of events. Second, while alcohol susceptibility is a significant, unique predictor of change in alcohol consumption among adolescents (McClure et al., 2009) in the US, longitudinal research is needed to confirm if exposure to AUF has a similar effect on Latin-American teenagers. Third, the samples may not be representative of the entire Argentinean or Mexican populations, as schools were not randomly selected. Therefore, the observation that the Argentinian sample had higher risk for drinking and higher drinking rates could be a function of our sampling and not necessarily a reflection of how these countries compare vis-à-vis adolescent drinking. Finally, we examined exposure to only one type of entertainment media. We are not able to estimate how much overlap there is between exposure to AUF and exposure to alcohol use in television through programming or advertisements; additional research is needed to clarify the contributions of these sources.

Despite its limitations, this study confirms that the association between exposure to AUF and uptake drinking found in other countries exists in Latin America. Taken together with multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal studies published to date, the results strongly suggest that steps to decrease exposure of adolescents to AUF could prevent some young people from transitioning to problem drinking. The combined evidence implicates movies as a disease vector (think influenza) that begins in one country (the United States, where Hollywood movies are made) and may affect alcohol use, not only among US adolescents, but also in most other western nations, where Hollywood movies are a staple in the media diets of children and adolescents. As mentioned above, alcohol companies pay to have alcohol placed in these movies, so they represent a form of marketing. Moreover, alcohol use is common in movies rated as appropriate for teens (Dal Cin et al., 2008b). What should be done to affect this vector?

Firstly, we know that the most effective way to address the film alcohol depictions would be to prohibit product placement. We know this because of our experience with cigarettes. Prohibition of cigarette brand placements that were imposed by the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement between major cigarette manufacturers and the US State Attorneys General heralded an exponential decline in cigarette brand placements, along with a substantial immediate decline in tobacco screen time (Bergamini et al., 2013). This suggests that similar restrictions on alcohol brand placement would also lower screen time and, therefore, youth exposure to this risk factor. More progress could be made in this area if the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to emphasize movie alcohol as part of their program to address youth exposure to alcohol advertising. The CDC could post annual reports on movie alcohol that included titles and companies, just as they do for smoking in movies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Secondly, the Motion Picture Association of America could take movie alcohol more seriously by conferring an adult rating for any depictions of youth or young adult drinking, partying, or drunkenness. This would move the most objectionable alcohol depictions out of youth-targeted movies, which have much higher youth viewership compared to adult-rated movies (Sargent et al., 2007).

In summary, youth exposure to alcohol depictions in movies is widespread and consistently linked with problematic alcohol use. It is time to do something about it.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers TW009274 (MPI Sargent & Thrasher) and CA077026 (PI Sargent). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None conflicts of interest

References

- ALDERETE E, KAPLAN CP, GREGORICH SE, MEJIA R, PEREZ-STABLE EJ. Smoking behavior and ethnicity in Jujuy, Argentina: evidence from a low-income youth sample. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:632–46. doi: 10.1080/10826080902809717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON P, DE BRUIJN A, ANGUS K, GORDON R, HASTINGS G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:229–43. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAHR SJ, HOFFMANN JP, YANG X. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. J Prim Prev. 2005;26:529–51. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGAMINI E, DEMIDENKO E, SARGENT JD. Trends in tobacco and alcohol brand placements in popular US movies, 1996 through 2009. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:634–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALLAS PW, FLYNN BS, WORDEN JK. Potentially modifiable psychosocial factors associated with alcohol use during early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1503–15. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION [July 29 2015];Smoking in the Movies [Online] 2015 Available: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/movies/

- CONSEJO NACIONAL DE POBLACIÓN . Indice de Marginación Urbana [Online] Mexico, D.F.: 2010. [October 14 2015]. Available: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/en/CONAPO/Indice_de_marginacion_urbana_2010. [Google Scholar]

- COURTNEY KE, POLICH J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:142–56. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPMAN S, FARRELLY MC. Four arguments against the adult-rating of movies with smoking scenes. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAL CIN S, STOOLMILLER M, SARGENT JD. Exposure to smoking in movies and smoking initiation among black youth. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAL CIN S, WORTH KA, DALTON MA, SARGENT JD. Exposure to Alcohol Use in Movies: Future Directions. Addiction. 2008a;103:1937–1938. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAL CIN S, WORTH KA, DALTON MA, SARGENT JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008b;103:1925–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAL CIN S, WORTH KA, GERRARD M, STOOLMILLER M, SARGENT JD, WILLS TA, GIBBONS FX. Watching and drinking: expectancies, prototypes, and friends' alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychol. 2009;28:473–83. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DALTON MA, TICKLE JJ, SARGENT JD, BEACH ML, AHRENS MB, HEATHERTON TF. The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Prev Med. 2002;34:516–23. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGELS RC, HERMANS R, VAN BAAREN RB, HOLLENSTEIN T, BOT SM. Alcohol portrayal on television affects actual drinking behaviour. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:244–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVERETT SA, GIOVINO GA, WARREN CW, CROSSETT L, KANN L. Other substance use among high school students who use tobacco. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:289–96. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDON R, MACKINTOSH AM, MOODIE C. The impact of alcohol marketing on youth drinking behaviour: a two-stage cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:470–80. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANT BF, DAWSON DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10:163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANEWINKEL R, MORGENSTERN M, TANSKI SE, SARGENT JD. Longitudinal study of parental movie restriction on teen smoking and drinking in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103:1722–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANEWINKEL R, SARGENT JD. Longitudinal study of exposure to entertainment media and alcohol use among german adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123:989–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANEWINKEL R, SARGENT JD, HUNT K, SWEETING H, ENGELS RC, SCHOLTE RH, MATHIS F, FLOREK E, MORGENSTERN M. Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133:973–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANEWINKEL R, SARGENT JD, POELEN EA, SCHOLTE R, FLOREK E, SWEETING H, HUNT K, KARLSDOTTIR S, JONSSON SH, MATHIS F, FAGGIANO F, MORGENSTERN M. Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. 2012;129:709–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANEWINKEL R, TANSKI SE, SARGENT JD. Exposure to alcohol use in motion pictures and teen drinking in Germany. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1068–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINGSON R, HEEREN T, LEVENSON S, JAMANKA A, VOAS R. Age of drinking onset, driving after drinking, and involvement in alcohol related motor-vehicle crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2002;34:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HULL JG, BRUNELLE TJ, PRESCOTT AT, SARGENT JD. A longitudinal study of risk-glorifying video games and behavioral deviance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;107:300–25. doi: 10.1037/a0036058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEYES KM, SCHULENBERG JE, O'MALLEY PM, JOHNSTON LD, BACHMAN JG, LI G, HASIN D. Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: the influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1304–13. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOORDEMAN R, KUNTSCHE E, ANSCHUTZ DJ, VAN BAAREN RB, ENGELS RCME. Do we act upon what we see? Direct effects of alcohol cues in movies on young adults' alcohol drinking. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2011;46:393–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEMSTRA M, BENNETT NR, NEUDORF C, KUNST A, NANNAPANENI U, WARREN LM, KERSHAW T, SCOTT CR. A meta-analysis of marijuana and alcohol use by socioeconomic status in adolescents aged 10-15 years. Can J Public Health. 2008;99:172–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03405467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLURE AC, DAL CIN S, GIBSON J, SARGENT JD. Ownership of alcohol-branded merchandise and initiation of teen drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLURE AC, STOOLMILLER M, TANSKI SE, WORTH KA, SARGENT JD. Alcohol-branded merchandise and its association with drinking attitudes and outcomes in US adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:211–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDINA-MORA ME, VILLATORO-VELÁZQUEZ JA, FLEIZ-BAUTISTA C, TÉLLEZ-ROJO MM, MENDOZA-ALVARADO LR, ROMERO-MARTÍNEZ M, GUTIÉRREZ-REYES JP, CASTRO-TINOCO M, HERNÁNDEZ-ÁVILA M, TENA-TAMAYO C, ALVEAR-SEVILLA C, GUISA-CRUZ V. Encuesta Nacional de Adicciones 2011: Reporte de Alcohol. INPRF: Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Secretaría de Salud; México DF, México: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MORGENSTERN M, ISENSEE B, SARGENT JD, HANEWINKEL R. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011a;165:610–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORGENSTERN M, ISENSEE B, SARGENT JD, HANEWINKEL R. Exposure to alcohol advertising and teen drinking. Prev Med. 2011b;52:146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORGENSTERN M, SARGENT JD, SWEETING H, FAGGIANO F, MATHIS F, HANEWINKEL R. Favourite alcohol advertisements and binge drinking among adolescents: a cross-cultural cohort study. Addiction. 2014;109:2005–15. doi: 10.1111/add.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUNEZ-SMITH M, WOLF E, HUANG HM, CHEN PG, LEE L, EMANUEL EJ, GROSS CP. Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2010;31:174–92. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.495648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OFICINA DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS CONTRA LA DROGA Y EL DELITO (ONUDD) Informe subregional sobre uso de Drogas en población escolarizada. ONUDD; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- PATRICK ME, SCHULENBERG JE. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Res. 2013;35:193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERCE JP, CHOI WS, GILPIN EA, FARKAS AJ, MERRITT RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REHM J, MATHERS C, POPOVA S, THAVORNCHAROENSAP M, TEERAWATTANANON Y, PATRA J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT J, WORTH K, BEACH M. Population-based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Communication Methods and Measures. 2008;2:134–151. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT JD. Smoking in movies: impact on adolescent smoking. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16:345–70. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT JD, TANSKI S, STOOLMILLER M, HANEWINKEL R. Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction. 2010;105:506–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT JD, TANSKI SE, GIBSON J. Exposure to movie smoking among US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years: a population estimate. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1167–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT JD, WILLS TA, STOOLMILLER M, GIBSON J, GIBBONS FX. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONEJI S, LEWIS VA, TANSKI S, SARGENT JD. Who is most susceptible to movie smoking effects? Exploring the impacts of race and socio-economic status. Addiction. 2012;107:2201–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SQUEGLIA LM, SPADONI AD, INFANTE MA, MYERS MG, TAPERT SF. Initiating moderate to heavy alcohol use predicts changes in neuropsychological functioning for adolescent girls and boys. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:715–22. doi: 10.1037/a0016516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAFF J, SCHULENBERG JE, BACHMAN JG. Adolescent Work Intensity, School Performance, and Academic Engagement. Sociol Educ. 2010;83:183–200. doi: 10.1177/0038040710374585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOOLMILLER M, GERRARD M, SARGENT JD, WORTH K, GIBBONS FX. R-rated Movie Viewing, Growth in Sensation Seeking and alcohol initiation: Reciprocal and Moderation Effects. Prev Sci. 2010;11:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOOLMILLER M, WILLS TA, MCCLURE AC, TANSKI SE, WORTH KA, GERRARD M, SARGENT JD. Comparing media and family predictors of alcohol use: a cohort study of US adolescents. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000543. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANSKI SE, STOOLMILLER M, GERRARD M, SARGENT JD. Moderation of the association between media exposure and youth smoking onset: race/ethnicity, and parent smoking. Prev Sci. 2012;13:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THRASHER JF, JACKSON C, ARILLO-SANTILLAN E, SARGENT JD. Exposure to smoking imagery in popular films and adolescent smoking in Mexico. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THRASHER JF, SARGENT JD, VARGAS R, BRAUN S, BARRIENTOS-GUTIERREZ T, SEVIGNY EL, BILLINGS DL, ARILLO-SANTILLÁN E, NAVARRO A, HARDIN J. Are movies with tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sex, and violence rated for youth? A comparison of rating systems in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. The International journal on drug policy. 2014;25:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAYLEN A, LEARY S, NESS A, SARGENT J. Alcohol use in films and adolescent alcohol use. Pediatrics. 2015;135:851–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLS TA, SARGENT JD, GIBBONS FX, GERRARD M. Movies Exposure to Alcohol Cues and Adolescent Alcohol Problems: A Longitudinal Analysis in a National Sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:23–35. doi: 10.1037/a0014137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION . Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]