Summary

Wang and colleagues demonstrate that digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) identified ESR1 mutations in 7% of primary breast cancers. ESR1 mutations were also readily detected in metastatic tissues and circulating tumor DNA in the blood. These results suggest that ddPCR may be amendable for monitoring tumor burden, and to predict relapse.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, using an ultrasensitive digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) technique, Wang et al. demonstrate that some of the ESR1 mutations reported in metastatic tumors are indeed present in primary breast tumors (1). In the past two years using next generation sequencing, researchers have confirmed that the ligand binding domain (LBD) of the estrogen receptor (ESR1 gene) is frequently mutated in approximately 20% of metastatic breast cancers, and these somatic mutations can arise in ER-positive cancer metastases after progression on endocrine therapy (2, 3). In their study, Y537S, Y537C and D538G ESR1 mutations were found at low allele frequencies in 7% (3/43) of primary tumors. Previously, it was generally accepted that ESR1 mutations were either very low (<1%) or undetectable in primary breast cancer. However, Takeshita et al., also using ddPCR, reported an ESR1 mutation rate of 2.5 % (7/270) in primary tumors (4). The differences in mutation frequency between these two studies probably reflect differences in selected cut-off values however these studies highlight that ESR1 mutations might be present in primary breast tumors at levels below detection using next generation sequencing. Whether ESR1 mutation status in primary tumors is associated with outcomes of endocrine therapy is an important clinical issue, but neither study was powered to address this critical question.

Recently circulating blood biomarkers, such as circulating tumors cells (CTCs) and cell-free plasma tumor DNA (cfDNA) have been considered as alternative sources of tumor material, especially since sampling of metastatic biopsies is often not practical, or biopsies do not yield sufficient material for analysis. High-depth targeted massively parallel sequencing (MPS) analysis of cfDNA has revealed the genomic complexity and extensive intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity of breast tumors (5), thus single tissue biopsies may not represent an ideal source for global monitoring of metastatic disease course. Emerging data demonstrate that ESR1 mutations and mutational profiles can often vary between metastatic sites within a patient (6). Wang et al. also conducted longitudinal monitoring of ESR1 mutation status in the cfDNA of four patients, and found that ESR1 mutation allele frequencies changed during treatment, and they conclude that ddPCR assays could potentially monitor tumor burden in treated patients. These anecdotal data complement what has been shown using MPS of cfDNA where response to treatment was associated with reductions in the level of potential driver mutations (7). Importantly, mutation tracking of serial patient cfDNA samples after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identified early breast cancer patients at high risk of relapse, whereas mutations in baseline cfDNA prior to treatment was not statistically associated with disease-free survival (8). Collectively these data suggest that evolving mutations in residual or micrometastatic disease before relapse may be useful to follow treatment response or to identify new therapeutic targets in metastatic disease.

The results to date also suggest that ESR1 mutations are frequently acquired during progression of hormone resistance, especially in the context of estrogen deprivation therapy with aromatase inhibitors. Unfortunately there are no clinical data to fully defend this conclusion. Serial blood sampling in the Wang study revealed three polyclonal ESR1 mutations in one patient, with enrichment of Y537C and D538 mutations, but loss of a Y537S mutation in a subsequent sample after treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, the mTOR inhibitor everolimus, and chemotherapy (1). In addition, Wang et al. found that ESR1 mutations could present in cfDNA but not in biopsied metastatic tissues, suggesting that cfDNA might be a better “snapshot” of tumor heterogeneity and evolution of multiple metastatic sites during treatment. Chu et al have recently reported a prospective sampling from metastatic breast cancer patients where no ESR1 mutations were detected in metastatic tissues, but ddPCR was able to detect them in half of the patients (9). Interestingly, in the Takeshita study two patients acquired ESR1 mutations in their metastatic lesions without intervening endocrine therapy, thus mutations can arise without endocrine selection (4). Although it has been suggested that the hormone-independent activity of these LBD mutant receptors could confer a selective advantage during estrogen deprivation therapy, it is also possible they confer a selective growth advantage or an enabling driver metastatic function in the absence of treatment (10). An enrichment in allele frequencies of the LBD ESR1 mutations in metastatic disease compared to primary breast tumors also supports an important role in metastatic tumor dissemination (7, 11).

A remaining important clinical question is whether the ESR1 mutations are actionable? Preclinical data are supportive that they can be targeted clinically. The LBD ESR1 mutations confer partial resistance to both tamoxifen and the ER degrader fulvestrant, therefore effective treatment will probably require better antiestrogens (2, 3). The Chu study reported a noteworthy patient with bone only ER-positive metastatic disease who developed an ESR1 mutation while on the aromatase inhibitor letrozole, but who is clinically without evidence of progression on fulvestrant (9). This demonstrates that ESR1 mutations do not necessarily exclude a response to fulvestrant. ESR1 mutations occur along with wild-type receptor in tumors, thus responses to hormonal agents can be achieved via blockade of the normal receptor. Two new antiestrogens with mixed selective estrogen receptor modulator/degrader activity (bazedoxifene and pipdendoxifene) were shown to be effective in an acquired tamoxifen-resistant model expressing wild-type ESR1, and bazedoxifen treatment alone significantly inhibited growth of a human patient-derived mouse xenograft model expressing the Y537S ESR1 mutation (12). Whether inhibition of other survival/growth pathways, such as cyclins CDK4/6 or mTOR, in combination with agents with improved mixed antiestrogen activities will provide additional benefit or synergy in ESR1 mutant tumors remains to be determined. In an innovative study using ex vivo culture of CTCs, Yu et al. demonstrates that targeting heat shock protein 90, an ER chaperone, was effective in treating the Y537S ESR1 mutation in combination with an antiestrogen and fulvestrant (11). An emerging picture is that targeted therapy for ESR1 mutations may be best determined by a complete understanding of the genomic complexity and molecular portrait of each patient. Individual treatment response for ESR1 patients should be determined in a cell-type specific way.

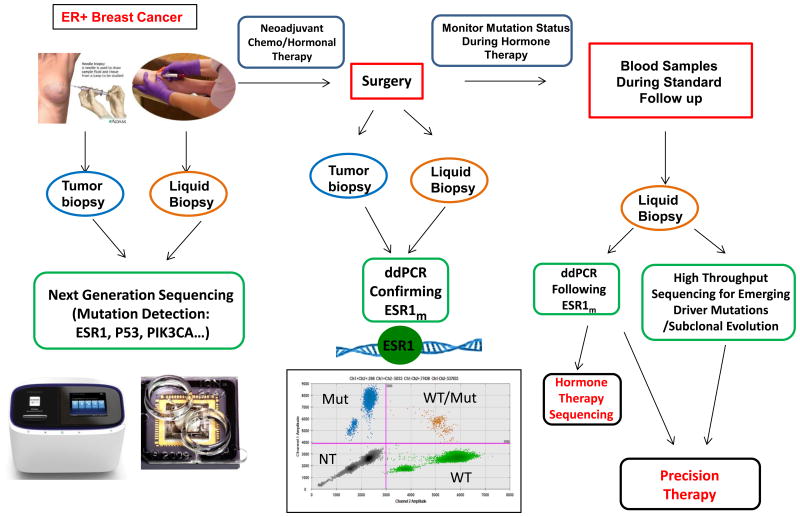

Women with ER-positive breast cancer fear relapse during and after adjuvant therapy. We currently have no systematic genomic followup during this time period, and a potential treatment paradigm is shown in Fig. 1. At the time of diagnosis, tumor tissue and baseline liquid biopsies could be used for mutation detection using sensitive next generation sequencing or MPS. Following neoadjuvant therapy, ddPCR could be employed to confirm ESR1 mutations. ddPCR could also be used to monitor mutation status during hormone therapy via blood sampling during standard followup visits. These liquid biopsies could also be used to monitor emerging driver mutations and subclonal evolution during therapy which would affect hormone therapy sequencing and enable precision therapy on an individual basis. The Wang study provides strong support for a call to action clinically for prospective investigation into the role of ESR1 mutations in hormone resistance and metastatic progression of breast cancer.

Fig. 1.

Upon diagnosis of breast cancer, both tumor biopsies and blood samples can be collected from ER-positive breast cancer patients. Baseline biopsies could be analyzed using next generation sequencing to detect relevant mutations in breast cancer such as ESR1, PIK3CA, p53, etc. Patients can receive chemotherapy or hormonal therapy before surgery. After neoadjuvant therapies, residual tumor biopsies and liquid biopsies can be collected and analyzed using ddPCR to confirm pre-existing mutations and compare mutation frequency with matched baseline patient samples. After surgery, mutation status is monitored by collecting patient liquid biopsies. ESR1 mutations can be assessed by ddPCR and other emerging driver mutations or subclonal evolution evaluated using high throughput captured sequencing. If ESR1 mutation allele frequencies increase in the plasma DNA, hormone therapy can be tailored to emerging mutations. This approach allows precision therapy for patients. Mut, mutated; NT, negative; WT, wild type.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: S.A.W. Fuqua is supported by the NCI of the NIH under award number R01CA72038, the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT RP120732), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Komen Foundation (PG12221410).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Wang P, Bahreini A, Gyanchandani R, Lucas PC, Hartmaier RJ, Watters RJ, et al. Sensitive detection of mono- and polyclonal ESR1 mutations in primary tumors, metastatic lesions and cell free DNA of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Oct 23; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1534. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1446–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, Green B, Sakr RA, Will M, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1439–45. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeshita T, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto-Ibusuki M, Inao T, Sueta A, Fujiwara S, et al. Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction assay for screening of ESR1 mutations in 325 breast cancer specimens. Transl Res. 2015;166(6):540–553. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng CK, Schultheis AM, Bidard FC, Weigelt BReis-Filho JS. Breast cancer genomics from microarrays to massively parallel sequencing: paradigms and new insights. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Mattos-Arruda L, Weigelt B, Cortes J, Won HH, Ng CK, Nuciforo P, et al. Capturing intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity by de novo mutation profiling of circulating cell-free tumor DNA: a proof-of-principle. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1729–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B, Ng C, Hrebien S, Cutts RJ, et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(302):302r. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0021. a133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu D, Paoletti C, Gersch C, VanDenBerg D, Zabransky D, Cochran R, et al. ESR1 mutations in circulating plasma tumor DNA from metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Aug 10; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0943. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuqua SA. The role of estrogen receptors in breast cancer metastasis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2001;6(4):407–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1014782813943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu M, Bardia A, Aceto N, Bersani F, Madden MW, Donaldson MC, et al. Cancer therapy. Ex vivo culture of circulating breast tumor cells for individualized testing of drug susceptibility. Science. 2014;345(6193):216–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1253533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardell SE, Ellis MJ, Alley HM, Eisele K, VanArsdale T, Dann SG, et al. Efficacy of SERD/SERM hybrid-CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations in models of endocrine therapy resistant breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(22):5121–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]