Abstract

Object

We present a retrospective cohort study examining complications in patients undergoing surgery for craniosynostosis using both minimally invasive endoscopic and open approaches.

Methods

Over the past ten years, 295 non-syndromic patients (140 endoscopic, 155 open) and 33 syndromic patients (10 endoscopic, 23 open) met our criteria. Variables analyzed included: age at surgery, presence of pre-existing CSF shunt, skin incision method, estimated blood loss (EBL), transfusions of packed red blood cells (PRBC), use of intravenous (IV) steroids or tranexamic acid (TXA), intraoperative durotomies, procedure length, and length of hospital stay. Complications were classified as either surgically or medically related.

Results

In the non-syndromic endoscopic group, we experienced 3 (2.1%) surgical and 5 (3.6%) medical complications. In the non-syndromic open group, there were 2 (1.3%) surgical and 7 (4.5%) medical complications. Intraoperative durotomies occurred in 5 (3.6%) endoscopic and 12 (7.8%) open cases, were repaired primarily, and did not result in reoperations for CSF leakage. Syndromic cases resulted in similar complication rates. No mortality or permanent morbidity occurred. Additionally, endoscopic procedures were associated with significantly decreased EBL, transfusions, procedure lengths, and lengths of hospital stay compared to open procedures.

Conclusions

Rates of intraoperative durotomies, surgical and medical complications were comparable between endoscopic and open techniques. This is the largest direct comparison to date between endoscopic and open interventions for synostosis, and the results are in agreement with previous series that endoscopic surgery confers distinct advantages over open in appropriate patient populations.

Keywords: craniosynostosis, craniofacial, surgical complications, endoscope, minimally invasive

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, the use of minimal incision craniectomy for craniosynostosis has increased as an alternative to full exposure craniectomy or calvarial vault reconstruction.2,31 Differences in utilization and opinions regarding outcomes of these techniques differ among surgeons specializing in the care of these conditions.7,24 Outcome variables debated include magnitude and durability of head shape improvement, cost, neurodevelopmental trajectory, burden of care to patient, and intra- and postoperative complication rates.4,32 The purpose of this work was to ascertain the incidence of intra- and postoperative complications in a single center. Although a number of studies have reported on various metrics of success in endoscopic10,13,15 or open9,28 craniosynostosis surgeries, few have directly compared results of the two on a large cohort of patients.6,17 We present a retrospective study examining complications after surgery in non-syndromic and syndromic cases of craniosynostosis.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study at St. Louis Children’s Hospital determined rates and causes of complications in patients undergoing endoscopic and open craniosynostosis surgery between 2003 and 2013. All patients receiving these operations during the study period were included in the analysis. The study compared complications related to: age at surgery, affected sutures, presence of pre-existing CSF shunt, skin incision method, estimated blood loss (EBL), intraoperative and postoperative transfusions of packed red blood cells (PRBC), use of IV steroids or tranexamic acid (TXA), procedure length, length of hospital stay, and re-admissions within 30 days. The Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved this study (IRB# 201206035).

Study Patients

Eligible patients included those with sagittal, metopic, unicoronal, lambdoid, bicoronal, squamosal, or multi-suture craniosynostosis diagnosed by a craniofacial team that included 1 pediatric neurosurgeon (M.D.S.) and 3 plastic surgeons (K.B.P., A.A.K., and A.S.W.). Craniosynostosis was diagnosed through a combination of physical examination, skull radiographs, and 3D head computed tomography (CT) scans. Our center routinely obtains a preoperative, low-dose 3D head CT on patients with suspected craniosynostosis if not already performed prior to referral. All patients fulfilling these criteria were included regardless of clinical follow-up lengths. We classified events as surgical complications (intraoperative excluding durotomies), intraoperative durotomies, or medical complications (postoperative). Separate analyses were conducted for syndromic and non-syndromic craniosynostosis cases.

Operative Technique

Both endoscopic and open procedures were offered to all patients presenting earlier than 6 months of age. We considered comorbidities, syndromes, and anticipated difficulties with postoperative helmet molding before making a final determination to use the endoscopic approach. Patients who presented after 6 months of age were offered an open operation only. Because it is the most common type of non-syndromic single-suture craniosynostosis, we describe the open and endoscopic procedures for premature fusion of the sagittal suture below.

Cranial Vault Remodeling for Sagittal Craniosynostosis

We utilize a bicoronal zigzag incision posterior to the coronal suture and behind the insertion of the temporalis muscle. A subperiosteal plane is developed to expose the cranial vault. The scalp and periosteum are retracted to expose the frontal and parietal bones. Next, we perform bilateral parietal (± frontal) craniotomies and utilize Tessier bone benders and osteotomies to reshape the cranial vault. After contouring, we secure the bones with an absorbable plating system. We place a subgaleal drain in most open cases. Technique varies slightly depending on the craniofacial plastic surgeon involved. Additional details have been previously published.29

Endoscope-Assisted Craniectomy for Sagittal Craniosynostosis

For endoscopic suturectomy, we utilize a transverse incision just posterior to the anterior fontanelle and another transverse incision just anterior to the lambda. We then place burr holes at each incision, strip the dura from the inner table of the skull, and use curettes and rongeurs to remove bone across the midline. We then strip the dura assisted by the endoscope to allow for our craniectomies and any other planned osteotomies. After the planned bone is removed, we use electrocautery and hemostatic agents to obtain hemostasis. From 2006–2011 we performed wide vertex craniectomies with parietal wedge osteotomies as described in detail by Jimenez/Barone,16,29 and since 2011 have switched to narrow strip craniectomies as detailed by Proctor.26

Hospital Course and Follow-Up

Patients who underwent open procedures were admitted to the pediatric intensive care units overnight with postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit monitoring to determine whether transfusion was required. Typically blood products were given in the operating room, but postoperative transfusions were performed when a patient was symptomatic or had a hematocrit lower than 21–24%, depending on subgaleal drain outputs and overall status. Patients received antibiotic prophylaxis as long as the subgaleal drain was in place. These patients were evaluated 3 weeks after discharge, and the majority returned for a 1-year follow-up evaluation.

Patients receiving endoscopic operations were admitted to the neurosurgical ward and also underwent postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit monitoring. In general, these patients were observed and discharged to home the next day. The threshold for transfusion was a hematocrit of less than 18%. They were fitted for cranial molding helmets in the first week after surgery and received continuing helmet therapy under the supervision of orthotists until 12 months of age. During this time, they typically outgrew one helmet and used two or three total.23,32 Endoscopic patients were evaluated every 2 to 3 months by our team to ensure adequate cranial remodeling.

During the latter part of the series, dexamethasone was used for scalp and facial edema, and TXA was used to minimize intraoperative blood loss in some cases, but not in a standardized fashion.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

For each patient, we reviewed all available clinical data including intraoperative surgery and anesthesia notes, ICU progress reports, lab results, helmet fitting appointments, clinical evaluations, and reoperations. Estimated blood loss (EBL) was obtained from anesthesia records, and a weight-based calculation was made for estimated blood volume (EBV). For infants less than 2 years old, EBV = (weight in kg) × (80 mL/kg). The percentage of EBV lost during the surgical procedure (EBL/EBV ratio = EBL/EBV × 100%) was then calculated.32

All events were classified as surgical complications, intraoperative durotomies, or medical complications (Table 1). Data for continuous variables were presented as mean ± one standard deviation. Statistical computations were performed using SPSS (version 22, IBM Corporation) with Student’s t-test for continuous variables or Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical data. Dunn-Šidák correction for multiple comparisons was applied based on an original α = 0.05 to determine statistical significance. Significance levels are listed separately on each relevant table.

Table 1.

Classification of events

| Group | Events included |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Surgical complications | scalp abscess, oxygen desaturation, intraoperative reintubation, hemodynamic instability, CSF leak, cranial defect, dural dehiscence |

| Intraoperative durotomies | intraoperative durotomies |

| Medical complications | stridor, upper airway obstruction, tachycardia, bradycardia, coagulopathy, hypertension, erythema, continued facial edema, seizure, fever, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, allergic reaction |

RESULTS

Patient Population

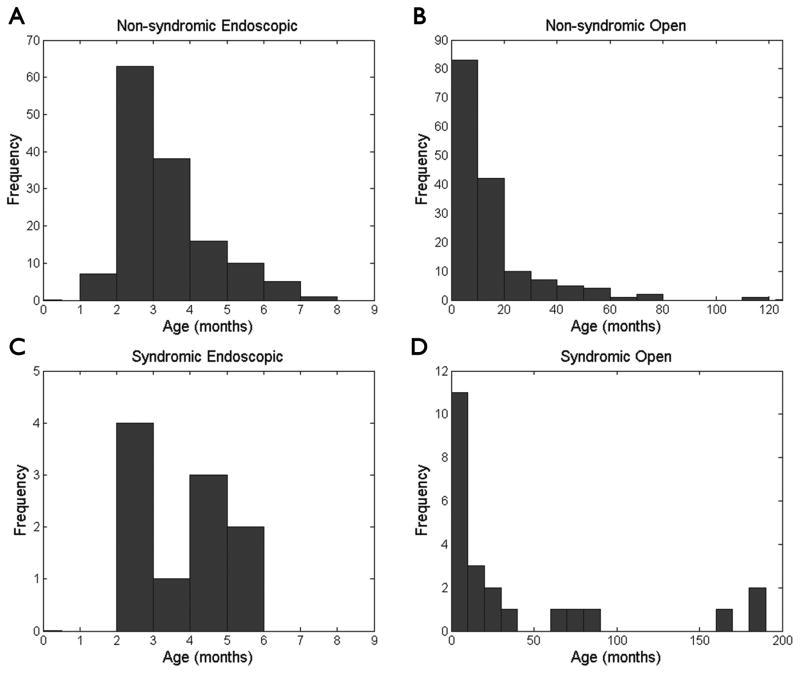

In the 10 year span, 295 non-syndromic craniosynostosis patients (140 endoscopic, 155 open) and 33 syndromic patients (10 endoscopic, 23 open) underwent surgical correction by our craniofacial team. For each of these patients, only initial operations to correct synostosis were included in our analysis. Of the non-syndromic cases, patients receiving endoscopic surgery had a mean age at surgery of 3.4 ± 1.2 months (mean ± standard deviation, Fig. 1) and were followed postoperatively for a duration of 25.2 ± 19.3 months (range 0.4 – 88.1), while those undergoing open procedures had a mean age at surgery of 15.5 ± 16.5 months (Fig. 1) and were followed postoperatively for 37.4 ± 30.2 months (range 0.1 – 125.4). None of the non-syndromic endoscopic patients had pre-existing shunts for comorbid hydrocephalus, while 4 (2.6%) of the open cases had pre-existing CSF shunts (Table 2). In fact, the presence of shunted hydrocephalus precluded us from offering an endoscopic approach due to concerns that head shape may not normalize while the draining force of the shunt counteracts brain expansion required for remodeling in the molding helmet.

FIG. 1.

Plots of the frequencies of patient ages comparing (A) non-syndromic endoscopic, (B) non-syndromic open, (C) syndromic endoscopic, and (D) syndromic open procedures. The distributions reveal that within both non-syndromic and syndromic groups, patients undergoing endoscopic procedures were significantly younger than those undergoing open operations (non-syndromic p < 0.001, syndromic p = 0.005, Student’s t-test).

Table 2.

Summary statistics (non-syndromic)

| Endoscopic | n | Open | n | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (months) †* | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 140 | 15.5 ± 16.5 | 155 | <0.001 |

| Pre-placed shunt | 0 | 139 | 4 (2.6%) | 155 | 0.125 |

| Scalpel | 74 (52.9%) | 140 | 57 (36.8%) | 155 | 0.006 |

| Bovie | 8 (5.7%) | 140 | 64 (41.3%) | 155 | <0.001 |

| EBL (cc)* | 36.1 ± 26.9 | 140 | 293.2 ± 180.2 | 151 | <0.001 |

| EBV (cc)* | 488.5 ± 81.1 | 140 | 809.1 ± 333.1 | 150 | <0.001 |

| EBL/EBV ratio (%)* | 7.5 ± 5.3 | 140 | 37.8 ± 21.4 | 146 | <0.001 |

| Intraoperative transfusions (PRBC) | 7 (5.0%) | 139 | 147 (96.1%) | 153 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative transfusions (PRBC) | 7 (5.0%) | 140 | 56 (39.4%) | 142 | <0.001 |

| IV steroids | 9 (6.6%) | 137 | 30 (27.0%) | 111 | <0.001 |

| TXA | 8 (5.8%) | 137 | 22 (20.2%) | 109 | <0.001 |

| Procedure length (minutes)* | 71.3 ± 24.8 | 140 | 168.5 ± 126.3 | 155 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days)* | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 139 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 151 | <0.001 |

| Surgical complications | 3 (2.1%) | 140 | 2 (1.3%) | 155 | 0.671 |

| Intraoperative durotomies | 5 (3.6%) | 140 | 12 (7.8%) | 154 | 0.140 |

| Medical complications | 5 (3.6%) | 140 | 7 (4.5%) | 154 | 0.773 |

| Re-admit (<30 days) | 2 (1.4%) | 140 | 2 (1.3%) | 154 | 0.921 |

| Length of follow-up (months) | 25.2 ± 19.3 (range: 0.4 – 88.1) | 140 | 37.4 ± 30.2 (range: 0.1 – 125.4) | 155 | <0.001 |

Level of significance: 0.00285

Values expressed as means ± one standard deviation.

See age distributions in Fig. 1.

EBL = estimated blood loss, EBV = estimated blood volume, PRBC = packed red blood cells, TXA = tranexamic acid.

Syndromic patients included those with chromosomal deletions, Goldenhar, Crouzon, Charcot-Marie-Tooth, Saethre-Chotzen, DiGeorge, Down, VATER (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula and/or esophageal atresia, renal and radial anomalies and limb defects), and CDAGS (craniosynostosis, anal anomalies, porokeratosis). Endoscopic syndromic patients had a mean age at surgery of 3.8 ± 1.3 months (Fig. 1) and were followed postoperatively for 36.8 ± 26.2 months (range 2.3 – 74.9). Open syndromic patients had a mean age at surgery of 41.4 ± 58.3 months (Fig. 1) and were followed postoperatively for 36.9 ± 28.5 months (range 0.1 – 113.6). Of our syndromic patients, 1 out of the 10 endoscopic cases and 4 out of the 23 open cases had pre-existing shunts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary statistics (syndromic)

| Endoscopic (n=10) | Open (n=23) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Syndromes | chromosomal deletions, Goldenhar, Crouzon, Charcot-Marie-Tooth, Saethre-Chotzen, DiGeorge, Down, VATER, CDAGS | ||

| Age at surgery (months) †* | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 41.4 ± 58.3 | 0.005 |

| Pre-placed shunt | 1 | 4 | 0.521 |

| Number of sutures | Single (4); Double (5); ≥3 (1) | Single (11); Double (6); ≥3 (5) | 0.626 |

| Scalpel : Bovie | 5 : 3 | 5 : 12 | 0.444 |

| EBL (cc)* | 42.8 ± 29.6 | 488.0 ± 421.2 | <0.001 |

| EBV (cc)* | 461.3 ± 65.3 | 1226.3 ± 1139.3 | 0.005 |

| EBL/EBV ratio (%)* | 8.2 ± 6.1 | 44.2 ± 23.3 | <0.001 |

| IV steroids | 2 | 5 | 0.694 |

| TXA | 1 | 2 | 0.582 |

| Procedure length (minutes)* | 129.7 ± 99.7 | 325.6 ± 130.5 | 0.001 |

| Length of stay (days)* | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Surgical complications | 0 | 2 | 0.510 |

| Intraoperative durotomies | 1 | 7 | 0.256 |

| Medical complications | 0 | 1 | 0.719 |

| Length of follow-up (months) | 36.8 ± 26.2 (range: 2.3 – 74.9) | 36.9 ± 28.5 (range: 0.1 – 113.6) | 0.760 |

Level of significance: 0.00341

Values expressed as means ± one standard deviation.

See age distributions in Fig. 1.

EBL = estimated blood loss, EBV = estimated blood volume, TXA = tranexamic acid.

Suture Locations

Early in the development of our endoscopic program we offered minimally invasive procedures more often to patients with sagittal synostosis, and later began to also offer them for coronal and metopic fusions as we gained experience and confidence in the technique. Therefore, our series included a higher rate of sagittal synostosis [94 (67.1%) endoscopic; 76 (49.0%) open] and a lower rate of unicoronal synostosis [10 (7.1%) endoscopic, 28 (18.1%) open] in the endoscopic group compared to open. Rates of metopic, lambdoid, bicoronal, and multiple (2-suture) synostosis were nevertheless comparable between the two groups. We used open procedures for 3 (1.9%) patients with 3-suture and 1 (0.6%) patient with 4-suture synostosis. None of these more severe non-syndromic multi-suture cases received endoscopic treatment (Table 4). Of our 10 syndromic endoscopic cases, 4 had single-suture, 5 had 2-suture, and 1 had ≥3-suture synostosis. Within our 23 syndromic open patients, 11 had single-suture, 6 had 2-suture, and 5 had ≥3-suture synostosis (Table 3).

Table 4.

Suture locations (non-syndromic)

| Endoscopic (n=140) | Open (n=155) | Combined (n=295) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sagittal | 94 (67.1%) | 76 (49.0%) | 170 (57.6%) |

| Metopic | 24 (17.1%) | 31 (20.0%) | 55 (18.6%) |

| Unicoronal | 10 (7.1%) | 28 (18.1%) | 38 (12.9%) |

| Lambdoid | 6 (4.3%) | 7 (4.5%) | 13 (4.4%) |

| Bicoronal | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Multi-suture (2*) | 7 (5.0%) | 8 (5.2%) | 15 (5.1%) |

| Multi-suture (3*) | 0 | 3 (1.9%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Multi-suture (4*) | 0 | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) |

Numbers in parentheses indicate number of fused sutures.

Skin Incisions

We examined methods used to make the initial skin incision in all patients with available data. Incisions were either performed sharply (scalpel) or with Colorado needle tip electrocautery. Some patients had partial incisions with both methods and we included them in the scalpel and unipolar electrocautery groups. Among non-syndromic patients, 52.9% of endoscopic cases had skin incisions with scalpel, compared to only 5.7% with electrocautery. The open non-syndromic cases were more evenly distributed, with 36.8% having skin incisions with scalpel and 41.3% with electrocautery (Table 2). Of the syndromic patients with available data, 5 endoscopic cases used a scalpel and 3 used electrocautery. Likewise, 5 syndromic open cases used a scalpel and 12 used electrocautery (Table 3).

Surgical Procedures

All subjects’ clinical data were reviewed for EBL, as well as PRBC, IV dexamethasone, and TXA usage during the intraoperative period. Additionally, we analyzed the average lengths of the various procedures and the lengths of postoperative hospital stays. It should be noted that within the endoscopic non-syndromic group, one patient was excluded from the length of stay calculation because he was an extreme outlier. This patient was complex with concomitant hydrocephalus, a tracheostomy, and had undergone cardiac surgery for a congenital heart defect. His operation was performed as an inpatient rather than as an elective outpatient basis. He was in the ICU for 43 days and stayed in the hospital for a total of 61 days after his synostosis operation.

Among the remaining non-syndromic endoscopic patients, we observed average EBL of 36.1 ± 26.9 cc, procedure length of 71.3 ± 24.8 minutes, and postoperative length of stay of 1.1 ± 0.3 days. In this group, 7 (5.0%) received intraoperative transfusions of PRBC, 7 (5.0%) received postoperative transfusions, 9 (6.6%) received steroids, and 8 (5.8%) received TXA. The non-syndromic open cases had average EBL of 293.2 ± 180.2 cc, procedure length of 168.5 ± 126.3 minutes, and length of stay of 3.8 ± 1.3 days. Furthermore, 147 (96.1%) of open patients received PRBC intraoperatively, 56 (39.4%) received PRBC postoperatively, 30 (27.0%) received steroids, and 22 (20.2%) received TXA (Table 2).

Focusing on our 10 syndromic endoscopic cases, we found average EBL of 42.8 ± 29.6 cc, procedure length of 129.7 ± 99.7 minutes, and length of stay of 1.4 ± 0.7 days. Steroids were given in 2 patients, and TXA in 1. Finally, in our 23 syndromic open patients, we observed average EBL of 488.0 ± 421.2 cc, procedure length of 325.6 ± 130.5 minutes, and length of stay of 3.6 ± 1.3 days. In this group, 5 patients received steroids and 2 received TXA (Table 3).

We were interested in determining whether pre-operative steroid administration led to shorter hospital stays among our various patient cohorts, but found no statistically significant differences in length of stay in any of our groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of pre-operative steroid administration on length of stay

| Group | LOS without steroids (days) * | n | LOS with steroids (days)* | n | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic non-syndromic | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 127 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 9 | 0.431 |

| Open non-syndromic | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 79 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 29 | 0.739 |

| Endoscopic syndromic | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 6 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 2 | N/A |

| Open syndromic | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 11 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 5 | N/A |

Level of significance: 0.0253. P values for the syndromic groups are not given as these results would be underpowered.

Values expressed as means ± one standard deviation.

LOS = length of stay.

Complications

We classified events as surgical complications, intraoperative durotomies, or medical complications (Table 1). Complications directly related to the operation itself or occurring during the intraoperative period were considered surgical, and those occurring during postoperative management of the patients were classified as medical. All intraoperative durotomies were repaired primarily through the existing skin incisions and did not result in reoperations for CSF leakage. No mortality or permanent morbidity occurred in any of these cases.

In the non-syndromic endoscopic group, we experienced 3 (2.1%) surgical complications, 5 (3.6%) intraoperative durotomies, and 5 (3.6%) medical complications. Readmissions within 30 days of their operations for any reason related to the procedures occurred in 2 (1.4%) of the total patients in this cohort. In the non-syndromic open group, there were 2 (1.3%) surgical complications, 12 (7.8%) intraoperative durotomies, and 7 (4.5%) medical complications. Readmissions within 30 days were recorded in 2 (1.3%) of non-syndromic open patients (Table 2). Syndromic endoscopic cases resulted in 1 intraoperative durotomy, no surgical complications, and no medical complications. Syndromic open cases included 2 surgical complications, 7 intraoperative durotomies, and 1 medical complication (Table 3).

Reoperations

In addition to complications, we also characterized all reoperations that were related to the patients’ craniosynostosis surgeries. We did not include operations related to other aspects of their management or follow-up procedures in planned two-stage operations. Among non-syndromic endoscopic patients, there were 2 reoperations for cranial defects and 1 for suboptimal aesthetics. In the non-syndromic open group, we had 1 reoperation for a chronically open wound, 2 for hematomas, 2 for removal of implants (wires, bone morphogenetic protein, or distractors), 2 for cranial defects, and 3 for suboptimal aesthetics. With our syndromic endoscopic patients, we had 3 reoperations for suboptimal aesthetics and 1 for a CSF leak related to a one-time trial of a distractor system. Finally, in our syndromic open cohort, we had 1 reoperation for implant removal, 1 for cranial defects, 6 for suboptimal aesthetics, and 2 for wound infections or abscesses.

Subgroup Analysis for Age <150 Days

We performed a subgroup analysis of all previously described data for patients less than 150 days old at time of surgery, comparing results of endoscopic and open operations for non-syndromic cases (Table 6). Although we were not able to fully control for age due to our limited number of subgroup patients receiving open procedures, the outcomes of this analysis are generally consistent with previous results.

Table 6.

Summary statistics (non-syndromic) for patients <150 days old at time of surgery

| Endoscopic | n | Open | n | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (days) * | 92.6 ± 24.7 | 124 | 132.4 ± 12.1 | 15 | <0.001 |

| Pre-placed shunt | 0 | 123 | 0 | 15 | 1.000 |

| Scalpel | 64 (51.6%) | 124 | 1 (6.7%) | 15 | 0.001 |

| Bovie | 7 (5.6%) | 124 | 9 (60.0%) | 15 | <0.001 |

| EBL (cc)* | 37.5 ± 27.6 | 124 | 245.7 ± 133.8 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Intraoperative transfusions (PRBC) | 7 (5.7%) | 123 | 15 (100.0%) | 15 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative transfusions (PRBC) | 7 (5.6%) | 124 | 8 (57.1%) | 14 | <0.001 |

| IV steroids | 8 (6.6%) | 121 | 1 (10.0%) | 10 | 0.522 |

| TXA | 7 (5.8%) | 121 | 0 | 10 | 0.434 |

| Procedure length (mins)* | 71.0 ± 25.3 | 124 | 117.5 ± 96.2 | 15 | 0.081 |

| Length of stay (days)* | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 123 | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 15 | <0.001 |

| Surgical complications | 2 (1.6%) | 124 | 1 (6.7%) | 15 | 0.292 |

| Intraoperative durotomies | 5 (4.0%) | 124 | 3 (20.0%) | 15 | 0.041 |

| Medical complications | 4 (3.2%) | 124 | 1 (6.7%) | 15 | 0.440 |

| Re-admit (<30 days) | 2 (1.6%) | 124 | 0 | 15 | 0.620 |

| Length of follow-up (years) | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 124 | 4.2 ± 2.7 | 14 | 0.015 |

Level of significance: 0.00320.

Values expressed as means ± one standard deviation.

EBL = estimated blood loss, mins = minutes, PRBC = packed red blood cells, TXA = tranexamic acid.

DISCUSSION

Craniosynostosis refers to premature fusion of one or more cranial vault sutures.25 It occurs in as many as 1 in 1700 live births, and can be characterized as single- or multi-suture, as well as syndromic or non-syndromic.11 In our study, we found that the most common location of non-syndromic single-suture synostosis is sagittal (57.6%, Table 4, combined data), followed in decreasing incidence by metopic (18.6%), unicoronal (12.9%), and unilambdoid (4.4%). Multi-suture cases including bicoronal represented 7.5% of the total. These results are generally in agreement with previously published large craniosynostosis series.12,20,30

In order to prevent stigma secondary to altered skull shape, as well as sequelae such as restricted brain growth and raised intracranial pressure resulting in neurological, cognitive, or visual impairment, patients with craniosynostosis should be carefully monitored or treated surgically.8,18,19 Surgical management of craniosynostosis has shifted from craniectomy to total cranial vault reconstruction, and more recently back to craniectomy due to the popularization of minimally invasive endoscopic approaches by Barone and Jimenez.1,2,31 Benefits of the endoscopic approach over more traditional open techniques include comparable safety and efficacy while allowing shorter operative times, reduced costs due to decreased hospital stays, and fewer blood transfusions.4,22,32 However, minimally invasive treatment is only possible in cases where early diagnosis and compliance with postoperative helmet therapy allow proper manipulation of the thin bones of young infants.4 Due to these constraints, surgeons vary widely in their opinions regarding the proper timing and indications for choosing an endoscopic versus open approach, or whether to offer an endoscopic approach at all.7,24

Patients at our center are generally offered the endoscopic technique if they are under 6 months of age at time of surgery,16 but other factors including comorbidities,3 syndromes,21 and anticipated difficulties with postoperative helmet molding6,33 must be considered as well. While some centers perform minimally invasive craniosynostosis surgery in children aged 6 to 9 months, our practice has been to limit the use of these endoscopic procedures to children under 6 months of age.27

Barone and Jimenez previously summarized the largest group of patients receiving endoscopic treatment for sagittal synostosis. Among 139 cases meeting the study criteria, the mean age was 3.6 months, perioperative blood transfusion rate was 9%, mean EBL was 29 cc, mean operative time was 58 minutes, and mean length of hospital stay was 1.07 days.17 They also reported similar findings for endoscopic correction of coronal synostosis in 115 patients.15 We included all types of craniosynostosis in our study population and found a mean age of 3.4 months, intraoperative blood transfusion rate of 5.0%, mean EBL of 36.1 cc, mean operative time of 71.3 minutes, and mean length of hospital stay of 1.1 days for endoscopic patients. All of these measures were significantly decreased from those of similar patients receiving open surgery, with the important difference that the open patients were older on average (15.5 months). Therefore, we conclude that although the improved metrics for endoscopic surgery reported by Barone et al. are reproducible across different patient populations, the advantages of minimally invasive surgery are partially confounded by selection bias for more advanced presentations, and potentially more difficult operations, in the open group. For comparison, Engel et al. reviewed 54 cases of open operations for non-syndromic metopic synostosis with a median age at operation of 11.5 months (range 6 to 52 months) and found median EBL of less than 255 ml (range 80 to 600 ml), 100% transfusion rate, and average length of hospital stay of 5 days.9 These results are similar to our findings for non-syndromic open operations (Table 2).

Chan et al. directly compared metrics in endoscopic versus open craniosynostosis surgery by examining a cohort of 21 open and 36 endoscopic patients receiving treatment for all types of craniosynostosis.6 They found a mean age at surgery of 10.56 months for open patients and 4.74 months for endoscopic patients. Our non-syndromic patients had average ages of 15.5 months (open) and 3.4 months (endoscopic) at time of surgery. For their open cases, Chan et al. reported average operating room time of 342 minutes, EBL of 280 cc, PRBC transfusion rate of 86%, and length of hospital stay of 4.9 days. Their endoscopic patients had an average operating room time of 133 minutes, EBL of 74 cc, PRBC transfusion rate of 55%, and length of stay of 1.25 days. Our results are largely comparable to those described in this previous study (Table 2). However, two differences between these two data sets should be noted. First, Chan et al. examined a combined cohort of syndromic and non-syndromic synostosis patients, while we analyzed syndromic cases separately. Second, the prior study reported operating room times from when the patients entered the operating room until the moment they exited, instead of the actual surgical procedure lengths that we described. Taking these factors into account, our larger dataset supports the notion set forth by previous studies that endoscopic synostosis surgery confers relative advantages over traditional open operations in the examined dimensions.

Our study sought to further elucidate the rates and natures of complications associated with endoscopic versus open craniosynostosis surgery, and to compare the results with the literature. Barone and Jimenez reported no infections, air emboli, intraoperative durotomies, intraparenchymal injuries, postoperative hematomas, seizures, or intraoperative deaths in their endoscopic sagittal synostosis series. However, they did describe superficial skin irritation along the incisions in 5 patients.17 In their endoscopic coronal synostosis series, Barone and Jimenez found no infections, sagittal sinus injury, postoperative hematomas, visual or ocular injuries, seizures, conversion to open procedures, or deaths. They did report 2 intraoperative durotomies, 2 minor scalp irritations, 3 calvarial defects, and 2 venous air emboli with a change in Doppler tones and decrease in end-tidal carbon dioxide, but no changes in blood pressure or oxygenation and of no clinical significance.15 Gociman et al. presented a series of 46 patients with non-syndromic sagittal synostosis who received endoscopic treatment and experienced no conversions to open approaches, reoperations, air emboli, cerebral parenchymal injuries, postoperative infections, hematomas, coagulopathies, CSF leaks, seizures, or deaths. They described 2 intraoperative durotomies that were repaired, and 8 patients who displayed pyrexia.13 Finally, a recent study from our group found similar rates of delayed synostosis of uninvolved sutures between open and endoscopic procedures in non-syndromic patients.35

In the present series, we classified events as surgical complications, intraoperative durotomies, or medical complications (Table 1). Within both our non-syndromic and syndromic groups, we found comparable rates of intraoperative durotomies, surgical and medical complications between endoscopic and open approaches (Tables 2 and 3). Therefore, our conclusion is that we can advocate either technique in most situations regardless of syndrome status.

With respect to the literature for complications related to endoscopic procedures, we report comparable rates of events in both our non-syndromic and syndromic endoscopic groups. Our rates in the non-syndromic endoscopic group are perhaps elevated compared to prior studies because we were more inclusive in what we considered complications (Table 1) and because our large study population revealed rare events that are less likely to be observed in smaller series. Finally, although our series shows similar rates of complications between endoscopic and open synostosis operations, the ultimate decision regarding the most appropriate approach depends on a combination of complications, outcomes, and patient factors. To this end, we have previously found outcomes of the two approaches to be similar for correction of sagittal synostosis.29

Wood et al. presented a discussion of the merits of scalpel versus unipolar electrocautery skin incisions for craniosynostosis surgery and found no statistically significant difference in wound complications, which was in agreement with most human clinical and animal studies. Additionally, they suggested that due to reported advantages of electrocautery including decreased incision time, improved hemostasis, and decreased postoperative pain, electrocautery is perhaps a more favorable method. However, they also acknowledged that the final decision to use scalpel or electrocautery for incisions is largely dependent on physician preference.34 Although we did not have data for all subjects, we reported our experience with utilization of scalpel versus electrocautery for initial skin incisions in this series. In general, we were much more likely to use scalpel for endoscopic patients, while our open cases were split evenly between the two methods (Table 2). To date, we have observed no notable differences in cosmetics or complications related to our decisions to use scalpel versus electrocautery for skin incisions.

Previous studies have provided strong evidence that TXA administration reduces blood loss.14 We attempted to corroborate these findings with our patients. First looking at all non-syndromic patients (endoscopic and open), we found that patients who received TXA (n = 30) had higher EBL (246.7 ± 225.4 cc) than those who did not receive TXA (137.5 ± 168.2 cc, n = 215). Because this result is contrary to previous findings, we conducted subgroup analyses to determine the cause of the discrepancy. Only 8 endoscopic patients were documented to have received TXA, so we did not have enough statistical power to draw conclusions based on this group. However, looking at only open non-syndromic cases with available data, and separating by plastic surgeons, we found that K.B.P. used TXA on all of his 19 open cases, whereas A.S.W. used it on only 3 of his 62, and A.A.K. did not administer TXA to any of his open non-syndromic patients. Therefore, the previous results are driven almost exclusively by K.B.P.’s open cases in the TXA group versus all three surgeons’ in the non-TXA group. Any findings are likely a result of more general variations between the surgeons rather than TXA administration. Based on these analyses, we conclude that our data lack statistical power and systematic design needed to corroborate findings from previous studies. Additionally, they reflect clear variations in practices between surgeons and suggest a need for a standardized protocol addressing TXA administration for future investigation.

One potential drawback of our study is that our standard follow-up for patients receiving endoscopic operations is shorter than those receiving open. Therefore, we are presenting earlier outcomes of endoscopic surgery. Longer follow-ups for both endoscopic and open synostosis corrections are needed to better understand and compare outcomes. Another note is that because the endoscopic procedures are limited to children under 6 months of age, open techniques are still the default for older patients. Older children are likely to bleed more, have thicker bone, and need more operative time, all of which might be reflected in our comparisons. We attempted to control for age by performing a subgroup analysis of non-syndromic patients less than 150 days old at time of surgery (Table 6), but still had significantly different mean ages between endoscopic and open groups due to small sample sizes. Nevertheless, this analysis yielded results similar to those obtained from the full series.

We used EBL as a point of comparison between open and endoscopic approaches in our study, but it should be acknowledged that this is a somewhat subjective estimation based on suction canister contents, sponges, and irrigation amounts with potential for variation between surgeons and anesthesiologists. Additionally, EBL is directly related to the weight and EBV of the child, which we attempted to address with our calculation of EBL/EBV ratio.

Finally, the decision of whether and when to transfuse in patients of varying ages is subject to a number of nuances that may have affected our results but not been explicitly addressed. For example, transfusion decisions in younger children are potentially more complicated due to compounded effects of preoperative NPO status, volume loading, and physiologic nadir leading to different thresholds for giving blood in younger versus older patients. Additionally, the final decision to transfuse is highly subjective and varies not just with surgeons, but also ICU staff and anesthesiologists. Combined with the difference in mean ages between open and endoscopic cases, these factors all potentially contribute to the results of our transfusion rate comparisons.

CONCLUSIONS

We present the largest direct comparison to date between endoscopic and open interventions for all types of craniosynostosis. Compared to open operations, endoscopic procedures were associated with decreased EBL, transfusions, procedure lengths, and lengths of hospital stay. Rates of intraoperative durotomies, surgical and medical complications were comparable between endoscopic and open techniques. These results are in agreement with previous series that although open reconstruction remains the only option in older children and results tend to be excellent, endoscopic techniques seem to offer clear advantages in appropriate populations such as decreased blood loss, shorter surgical times and shorter hospitalizations without an increase in morbidity.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented in poster form at the AANS/CNS Section on Pediatric Neurological Surgery Annual Meeting, Amelia Island, FL, USA, December 2–5, 2014.

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Barone CM, Jimenez DF. Endoscopic craniectomy for early correction of craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1965–1975. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199912000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barone CM, Jimenez DF. Endoscopic approach to coronal craniosynostosis. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmans B, Kammeraad JAE, van Adrichem LNA, Staals LM. Craniosynostosis surgery in an infant with a complex cyanotic cardiac defect. Pediatr Anesth. 2014;24:788–790. doi: 10.1111/pan.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry-Candelario J, Ridgway EB, Grondin RT, Rogers GF, Proctor MR. Endoscope-assisted strip craniectomy and postoperative helmet therapy for treatment of craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31:E5. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.FOCUS1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown L, Proctor MR. Endoscopically assisted correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. AORN J. 2011;93:566–582. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan JWH, Stewart CL, Stalder MW, St Hilaire H, McBride L, Moses MH. Endoscope-assisted versus open repair of craniosynostosis: a comparison of perioperative cost and risk. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:170–174. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182646ab8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doumit GD, Papay FA, Moores N, Zins JE. Management of sagittal synostosis: a solution to equipoise. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:1260–1265. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182a24635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eley KA, Johnson D, Wilkie AOM, Jayamohan J, Richards P, Wall SA. Raised intracranial pressure is frequent in untreated nonsyndromic unicoronal synostosis and does not correlate with severity of phenotypic features. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:690e–697e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318267d5ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel M, Thiele OC, Mühling J, Hoffmann J, Freier K, Castrillon-Oberndorfer G, et al. Trigonocephaly: results after surgical correction of nonsyndromatic isolated metopic suture synostosis in 54 cases. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2012;40:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erşahin Y. Endoscope-assisted repair of metopic synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:2195–2199. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fearon JA. Evidence-based medicine: craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1261–1275. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher DC, Kornrumpf BP, Couture D, Glazier SS, Argenta LC, David LR. Increased incidence of metopic suture abnormalities in children with positional plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:89–95. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f6c5a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gociman B, Marengo J, Ying J, Kestle JRW, Siddiqi F. Minimally invasive strip craniectomy for sagittal synostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:825–828. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824dbcd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goobie SM, Meier PM, Pereira LM, McGowan FX, Prescilla RP, Scharp LA, et al. Efficacy of tranexamic acid in pediatric craniosynostosis surgery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:862–871. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210fd8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jimenez DF, Barone CM. Early treatment of coronal synostosis with endoscopy-assisted craniectomy and postoperative cranial orthosis therapy: 16-year experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12:207–219. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.PEDS11191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez DF, Barone CM. Endoscopic technique for sagittal synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1333–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1768-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez DF, Barone CM, McGee ME, Cartwright CC, Baker CL. Endoscopy-assisted wide-vertex craniectomy, barrel stave osteotomies, and postoperative helmet molding therapy in the management of sagittal suture craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:407–417. doi: 10.3171/ped.2004.100.5.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirman CN, Tran B, Sanger C, Railean S, Glazier SS, David LR. Difficulties of delayed treatment of craniosynostosis in a patient with Crouzon, increased intracranial pressure, and papilledema. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:1409–1412. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31821cc50c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HQ, Hutson JM, Wray AC, Lo PA, Chong DK, Holmes AD, et al. Analysis of morbidity and mortality in surgical management of craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:1256–1261. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824e26d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HQ, Hutson JM, Wray AC, Lo PA, Chong DK, Holmes AD, et al. Changing epidemiology of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis and revisiting the risk factors. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318252d893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier PM, Goobie SM, DiNardo JA, Proctor MR, Zurakowski D, Soriano SG. Endoscopic strip craniectomy in early infancy: the initial five years of anesthesia experience. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:407–414. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820471e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier PM, Guzman R, Erb TO. Endoscopic pediatric neurosurgery: implications for anesthesia. Pediatr Anesth. 2014;24:668–677. doi: 10.1111/pan.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen DC, Patel KB, Skolnick GB, Naidoo SD, Huang AH, Smyth MD, et al. Are endoscopic and open treatments of metopic synostosis equivalent in treating trigonocephaly and hypotelorism? J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:129–134. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagnoni M, Fadda MT, Spalice A, Amodeo G, Ursitti F, Mitro V, et al. Surgical timing of craniosynostosis: what to do and when. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2014;42:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel A, Terner J, Travieso R, Clune JE, Steinbacher D, Persing JA. On Bernard Sarnat’s 100th birthday: pathology and management of craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:105–112. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240fb0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridgway EB, Berry-Candelario J, Grondin RT, Rogers GF, Proctor MR. The management of sagittal synostosis using endoscopic suturectomy and postoperative helmet therapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;7:620–626. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.PEDS10418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanger C, David L, Argenta L. Latest trends in minimally invasive synostosis surgery: a review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22:316–321. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaller BJ, Filis A, Merten HA, Buchfelder M. Premature craniosynostosis--the role of skull base surgery in its correction. A surgical and radiological experience of 172 operated infants/children. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2012;40:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah MN, Kane AA, Petersen JD, Woo AS, Naidoo SD, Smyth MD. Endoscopically assisted versus open repair of sagittal craniosynostosis: the St. Louis Children’s Hospital experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:165–170. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.PEDS1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer S, Bower C, Southall P, Goldblatt J. Craniosynostosis in Western Australia, 1980–1994: a population-based study. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83:382–387. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990423)83:5<382::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teichgraeber JF, Baumgartner JE, Viviano SL, Gateno J, Xia JJ. Microscopic versus open approach to craniosynostosis: a long-term outcomes comparison. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:1245–1248. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogel TW, Woo AS, Kane AA, Patel KB, Naidoo SD, Smyth MD. A comparison of costs associated with endoscope-assisted craniectomy versus open cranial vault repair for infants with sagittal synostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13:324–331. doi: 10.3171/2013.12.PEDS13320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong RK, Emelin JK, Meltzer HS, Levy ML, Cohen SR. Nonsyndromic craniosynostosis: the Rady Children’s Hospital approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:2061–2065. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318271cdd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood JS, Kittinger BJ, Perry VL, Adenola A, van Aalst JA. Craniosynostosis incision: scalpel or cautery? J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:1256–1259. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarbrough CK, Smyth MD, Holekamp TF, Ranalli NJ, Huang AH, Patel KB, et al. Delayed synostoses of uninvolved sutures after surgical treatment of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:119–123. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182a75102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]