Abstract

Specific viruses are associated with pediatric myocarditis, but the prevalence of viral DNAemia detected by blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is unknown. We evaluated the prevalence of known cardiotropic viruses (enterovirus, adenovirus, human herpesvirus 6, and parvovirus B19) in children with clinical myocarditis (n = 21). Results were compared to pediatric controls with similar viral PCR testing. The majority of positive PCR (89 %) was noted in children ≤12 months of age at diagnosis compared to older children. Infant myocarditis patients (8/10) had increased the prevalence of PCR positivity compared to infant pediatric controls (4/114) (p < 0.0001). Other than age, patient characteristics at diagnosis were similar between PCR-positive and PCR-negative patients. Both PCR-negative myocarditis infants had clinical recovery at follow-up. Of the PCR-positive myocarditis infants, 4 had clinical recovery, 2 developed chronic cardiomyopathy, 1 underwent heart transplant, and 1 died. Infants with clinical myocarditis have a high rate of blood viral positivity, which is higher compared to older children with myocarditis and healthy infant controls. Age-related differences in PCR positivity may be due to differences in host and/or virus characteristics. Our findings suggest that viral blood PCR may be a useful diagnostic tool and identify patients who would potentially benefit from virus-specific therapy.

Keywords: Myocarditis, DNAemia, Pediatric cardiology

Background

Myocarditis is an important cause of heart disease in children and recognized as a major cause of dilated cardiomyopathy [1, 6, 13, 16]. Several viruses have been commonly associated with the development of myocarditis in children [4, 7]. Linking viral serology and myocarditis has been challenging, but viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be a useful tool as it can identify viral nucleic acid present in patient blood samples, suggesting the presence of current infection. Currently, the prevalence of viral DNAemia in children with myocarditis is unknown. Within a multicenter pediatric myocarditis study, we evaluated for evidence of viral DNAemia using blood viral PCR to detect common viruses known to be related to the development of cardiac dysfunction. We hypothesized that the prevalence of viral DNAemia by PCR would be significantly higher in children with clinical myocarditis compared to healthy controls.

Methods

Patients <18 years of age were enrolled in a multi-institutional, observational study of children with a clinical diagnosis of myocarditis between April 2011 and October 2013 at six institutions. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each institution, with Washington University in St. Louis acting as the coordinating institution. All study participants underwent informed consent at study enrollment. Data from time of initial diagnosis through last follow-up were collected and analyzed.

Clinical myocarditis was defined by one of the following clinical scenarios: (1) biopsy-proven myocarditis by histiopathic evaluation using the “Dallas” criteria, (2) clinical diagnosis of myocarditis confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR), or (3) recent onset heart failure symptoms with the presence of LV shortening fraction age-specific z-score < −2 of unknown etiology. Patients were excluded if another cause of DCM was identified (i.e., familial, metabolic, ischemic, toxin).

Subjects who had blood viral PCR testing during routine initial evaluation were included in the analysis. In our study population, all of the myocarditis patients had PCR testing performed within 6 weeks of onset of their initial symptoms. Viral serology and PCR results from clinical specimens other than blood were not included in the analysis. We reviewed the results of blood PCR testing for four viruses known to be associated with pediatric myocarditis: the enterovirus group, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6). Although other viruses have also been associated with myocarditis, our analysis was limited to viruses commonly tested for at the participating study institutions. Endomyocardial biopsies were not obtained in the majority of patients, and therefore, PCR from endomyocardial tissue could not be compared to blood PCR results.

Selection of PCR assays to perform on blood was not specified by protocol and was at the discretion of physicians providing care at each institution. Likewise, PCR protocols were those in use at the individual institution and were not standardized between institutions. Consequently, not all study patients had viral PCR testing for each of the four viruses. Patients were considered viral PCR positive if they had at least one positive viral PCR. Patients were considered viral PCR negative if at least one viral PCR test was performed and PCR results were negative.

In order to determine how the PCR results compare to those found in healthy children, the prevalence of positive viral blood PCR in the myocarditis group was compared to the prevalence of these viruses in healthy pediatric controls who were tested in another study [3]. The control subjects were children 2–12 months of age who were having ambulatory surgery and were not acutely ill. Each control had blood viral PCR testing that included HHV6, parvovirus B19, enterovirus, and adenovirus according to that study protocol.

Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparing continuous data when appropriate. Fischer’s exact test was used for categorical data. Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or median with interquartile range (IQR) for nonparametric data when appropriate. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

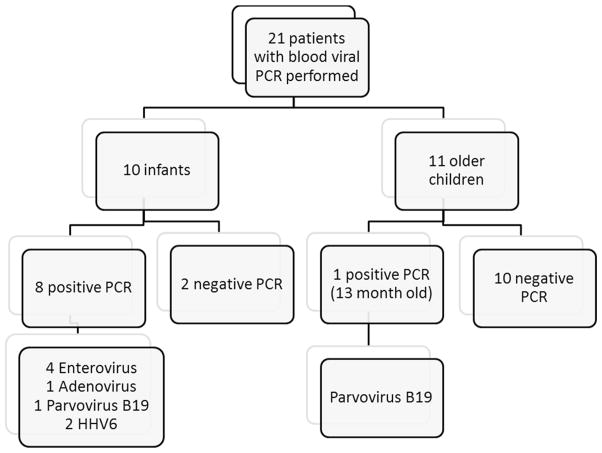

A total of 21 patients with myocarditis had blood viral PCR testing for at least one of the viruses of interest (Fig. 1). Overall, enterovirus PCR was performed in 19 patients, adenovirus PCR in 12 patients, parvovirus B19 PCR in 12 patients, and HHV6 in 11 patients. Of the 21 patients with available PCR results, 9 patients (43 %) had a positive blood viral PCR results, including 4 patients with enterovirus, 2 with parvovirus B19, 1 with adenovirus, and 2 with HHV6. No patient was positive for more than one virus.

Fig. 1.

Breakdown of pediatric myocarditis patients with PCR testing at presentation. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; HHV6, human herpesvirus 6

Patient characteristics at time of diagnosis were similar between patients with positive and negative blood viral PCR (Table 1), with the exception of age at diagnosis. Of the patients with a positive PCR, 8 of the total 9 patients (89 %) were ≤12 months old at time of testing. Duration of symptoms at diagnosis, electrocardiogram and chest X-ray findings, and echocardiographic measurements of LV size and function did not differ significantly based on the presence of a positive or negative viral PCR. There was no correlation between age at diagnosis and length of symptoms prior to diagnosis (Pearson correlation p = 0.457).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by blood viral PCR positivity

| Patient characteristic | Virus (n = 9) | No virus (n = 12) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median years (IQR) | 0.25 (0.04–0.84) | 5 (1.33–10) | 0.0007* |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 3 (33) | 7 (58) | 0.522 |

| Symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection | 6 (67) | 12 (100) | 0.114 |

| Chest pain | 0 | 2 (17) | 0.113 |

| Shock | 3 (33) | 0 | 0.109 |

| Length of symptoms, median days (IQR) | 4.5 (2–10) | 9 (4.5–14) | 0.132 |

| Abnormal chest X-ray at diagnosis, n (%) | 6 (67) | 10 (83) | 0.284 |

| Cardiomegaly | 6 (67) | 7 (58) | 0.322 |

| Effusion | 2 (22) | 2 (17) | 0.503 |

| Edema | 5 (56) | 2 (17) | 0.045* |

| Opacity | 2 (22) | 3 (25) | 0.816 |

| Abnormal electrocardiogram at diagnosis, n (%) | 8 (89) | 12 (100) | 0.357 |

| Conduction delay | 1 (11) | 2 (17) | 0.702 |

| Atrial or junctional tachycardia | 3 (33) | 2 (17) | 0.3 |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | 0 | 2 (17) | 0.37 |

| Low QRS voltage | 2 (22) | 0 | 0.163 |

| ST and T wave abnormality | 6 (67) | 6 (50) | 0.511 |

| Shortening fraction z-score at diagnosis, median (IQR) | −9.08 (−14.04 to 7.34) | −12.37 (−16.27 to 4.8) | 0.512 |

| Left ventricular dimensions by echocardiogram | |||

| Systolic, z-score, median (IQR) | 6.06 (2.8–17.5) | 9.03 (1.64–15.5) | 0.79 |

| Diastolic, z-score, median (IQR) | 2.5 (0.8–11.1) | 4.82 (0.89–8.8) | 0.73 |

Myocarditis patients with positive blood viral PCR with significantly younger and more likely to have pulmonary edema on chest X-ray at time of initial evaluation

IQR interquartile range, ECMO extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, VAD ventricular assist device, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin

p <0.05 was considered statistically significant

Infants with Clinical Myocarditis

The majority (89 %) of positive viral PCR results were observed in the infants with clinical myocarditis. A total of 10 myocarditis patients were ≤12 months at time of diagnosis, including 8 (80 %) infants who had a positive blood viral PCR. In comparison, only 1 of 11 children older than 12 months were positive (p = 0.0019). The median age at diagnosis for the entire group was 7 months (IQR 5–9.3 months) and tended to be younger in those with a positive PCR (2.5 vs. 8.5 months) although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.28). There was no significant difference in median time from symptom onset to testing (6 vs. 5.5 days, p = 1) or median LV SF % z-score by echocardiogram at presentation (−9.1 vs. −7.8, p = 0.71) between virus positive and negative infants.

The 8 PCR-positive infant patients presented with various symptoms, including recent viral prodrome (5), cardiogenic shock (2), and recent enterovirus meningitis (1). The 2 infants with negative viral PCRs presented with a recent gastrointestinal or respiratory viral prodrome. Both infants with negative PCRs clinically recovered. Of the PCR-positive infants, 4 clinically recovered, 2 developed chronic dilated cardiomyopathy, 1 underwent heart transplantation, and 1 died.

Comparison with Infant Controls

Although PCR positivity was more prevalent in the infants compared to older children with myocarditis, it was unclear whether this trend was related to higher prevalence of viral PCR positivity in the infants in general. Therefore, results were compared to a group of 114 healthy pediatric control patients ≤12 months old that underwent blood viral PCR testing as described above. The ages of the controls were similar to those of the children with myocarditis (median 6.5 vs. 7 months, p = 0.14). In total, only 4 (3.5 %) of the 114 control patients had a positive blood viral PCR for either adenovirus, enterovirus, parvovirus B19, or HHV6 compared to 8 of 10 of the infant study patients (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In our study of children with clinical myocarditis, we noted that 43 % of the patients who had blood viral PCR testing were positive at time of diagnosis for one of four common viruses known to be cardiotropic. Interestingly, the majority of the PCR positivity (89 %) was seen in the children ≤12 months of age with myocarditis. In that age group, 8 of 10 were PCR positive. The higher prevalence in infants cannot be simply explained by characteristics or exposure specific this age group as might be hypothesized, since infants with myocarditis had significantly higher rates of positivity compared to healthy infant controls. To our knowledge, our study is the first to report age-specific differences of viral DNAemia in children with myocarditis using blood viral PCR.

The reason for the increased blood viral PCR positivity in infants compared to older children is unclear. PCR testing was performed within 6 weeks of symptom onset in our study, but timing varied among patients. Although differences in timing of PCR could play a factor in age-related differences, there was no significant difference in length of symptoms prior to presentation based on patient age. One hypothesis is that the relative immaturity of the immune system in infants contributes to an increased rate of disseminated infection with DNAemia in the infant myocarditis patients. It is also possible that infants have a longer period of DNAemia than older children, making detection more likely.

Regardless of the specific reason for the increased DNAemia at presentation noted in our study, our findings raise the question of whether infants with myocarditis may benefit from targeted anti-viral therapy. Routine viral PCR testing and anti-viral therapies have previously had a limited role in the treatment of myocarditis as most patients are thought to develop symptoms after the acute viremic phase of disease [4]. Although we cannot clearly conclude from our current study, infants may be a subgroup of myocarditis patients that are more likely to present during the viremic phase. Blood viral PCR in infants presenting with probable myocarditis may be a valuable tool in diagnosing myocarditis and identifying potential candidates for anti-viral therapy. Additionally, routine testing with blood viral PCR to identify pediatric myocarditis patients with active DNAemia at presentation, particularly those patients with a more severe clinical course, may effect the decision to pursue heart transplantation in the setting of continued DNAemia and refractory heart disease.

Unfortunately, current options and experience with antiviral therapy for many common viruses associated with myocarditis are very limited. Most studies are limited to case reports and single-center experiences. Interferon beta (INF-β) has been shown to decrease coxsackievirus in cultured human myocardial cells [10]. INF-β therapy was associated with virus elimination and improvement in cardiac function in adults with DCM and enterovirus or adenovirus on endomyocardial biopsy [11]. Successful treatment of enterovirus myocarditis with interferon alpha was also reported in a small case series [5]. Several antiviral drugs are also in the development, but not all specific to patients with suspected myocarditis. For example, pleconaril has been effective in experimental enterovirus infections in mice [14] and more recently a small number of humans [2, 3, 15], but use has not been reported in myocarditis patients. Brincidofovir (CMX001) has been studied in the treatment of double-stranded DNA viruses, including in vitro studies with adenovirus, but human experience remains limited [8]. A case series of 13 patients with severe refractory adenovirus infections, although not including myocarditis, treated with CMX001 reported nearly 70 % of patients had a substantial decrease in detectable adenovirus DNA and had significantly improved survival compared to non-responders [9]. In murine models of coxsackievirus myocarditis, an experimental 3C pro-tease inhibitor reduced myocardial damage and mortality [17] as well as the development of the DCM phenotype after infection [12]. While these results are promising, whether virus-specific therapy in children with myocarditis can affect viral clearance and clinical outcomes remains unknown. Our findings suggest that future studies in children with myocarditis should include a uniform evaluation of blood viral PCR to validate our results in a larger prospective patient population. Hopefully, further studies will enhance our understanding as to whether blood viral PCR studies should be part of routine testing for possible myocarditis, particularly in the infant population.

Limitations

As a multi-institutional observation study, there are several important limitations. A substantial limitation is the lack of standardization regarding criteria for performing PCR, in which PCR assays were performed, and the performance characteristics of each assay, since they were performed in different laboratories. Other relevant variables that were not controlled include which blood component was tested (e.g., plasma vs. serum) and the timing of testing in relation to illness onset. Also, as noted, not all patients had testing for all four viruses of interest and patients may have also been positive for other viruses that were not included in this study analysis. It is possible that this may have led to underestimation of PCR positivity in the study population, as some patients may have been positive for a virus, but did undergo specific viral PCR testing at time of diagnosis. Finally, although there was no difference in age, the comparison with the control group is limited by other possible differences between the control group patient population and the myocarditis patients. Future studies would require standardization of sample testing and laboratory techniques to account for these factors.

Conclusion

Infants with clinical myocarditis have a high rate of blood viral positivity, which is higher compared to older children with myocarditis and healthy infant controls. This study was not prospective and was not standardized. Nevertheless, the result is interesting and should stimulate further studies to confirm the observation. If confirmed, blood viral PCR testing in infants presenting with possible myocarditis could be a useful adjunctive tool to standard diagnostic evaluation. Currently, anti-viral options are limited and potential to improve patient outcomes remains unclear. Age-related differences in PCR positivity may be due to differences in host and/or virus characteristics in infants with myocarditis; however, further research is required to determine factors related to viremia in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by research grants from the Myocarditis Foundation and the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and Saint Louis Children’s Hospital. Funding for the collection of control patient data was provided by Grant [UAH2AI083266-01] from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Grant [UL1 RR024992] from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources and Washington University Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences, and training Grant [T32HD049338] from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest No author has any potential conflicts of interest pertaining to this research study or manuscript.

References

- 1.Andrews RE, et al. New-onset heart failure due to heart muscle disease in childhood: a prospective study in the United kingdom and Ireland. Circulation. 2008;117(1):79–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer S, et al. Severe Coxsackie virus B infection in pre-term newborns treated with pleconaril. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(9):491–493. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0929-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colvin JM, et al. Detection of viruses in young children with fever without an apparent source. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1455–e1462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper LT., Jr Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1526–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daliento L, et al. Successful treatment of enterovirus-induced myocarditis with interferon-alpha. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(2):214–217. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daubeney PE, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of childhood dilated cardiomyopathy: results from a national population-based study. Circulation. 2006;114(24):2671–2678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durani Y, et al. Pediatric myocarditis: presenting clinical characteristics. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(8):942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florescu DF, Keck MA. Development of CMX001 (Brincidofovir) for the treatment of serious diseases or conditions caused by dsDNA viruses. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(10):1171–1178. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.948847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Florescu DF, et al. Safety and efficacy of CMX001 as salvage therapy for severe adenovirus infections in immuno-compromised patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(5):731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heim A, et al. Recombinant interferons beta and gamma have a higher antiviral activity than interferon-alpha in coxsackievirus B3-infected carrier state cultures of human myocardial fibroblasts. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16(4):283–287. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhl U, et al. Interferon-beta treatment eliminates cardiotropic viruses and improves left ventricular function in patients with myocardial persistence of viral genomes and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107(22):2793–2798. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072766.67150.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim BK, et al. Soluble coxsackievirus B3 3C protease inhibitor prevents cardiomyopathy in an experimental chronic myocarditis murine model. Virus Res. 2015;199:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipshultz SE, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1647–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pevear DC, et al. Activity of pleconaril against enteroviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(9):2109–2115. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotbart HA, Webster AD, Pleconaril G. Treatment registry, treatment of potentially life-threatening enterovirus infections with pleconaril. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(2):228–235. doi: 10.1086/318452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Towbin JA, et al. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1867–1876. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun SH, et al. Antiviral activity of coxsackievirus B3 3C protease inhibitor in experimental murine myocarditis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(3):491–497. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]