Abstract

In this simulation study, we present and examine methods to develop a feedback controller for a neuroprosthesis that restores forward and side leaning function during standing following complete, thoracic-level spinal cord injury. Achieving leaning postures away from erect stance with functional neuromuscular stimulation (FNS) would allow users to extend their reaching capabilities. Utilizing a 3-D computer model of human stance, an FNS control system based on total-body center of mass (CoM) kinematics (position, acceleration) is developed and tested in simulation. CoM kinematics drive an artificial neural network to modulate muscle excitations and reduce the upper extremity loading, presumably against a walker or similar support surface, required to resist the effects of postural perturbations. Furthermore, a novel method to robustly estimate the feedback kinematics for standing applications is also presented while assuming 3-D accelerometer signals at locations consistent with a proposed implantable networked neuroprosthesis system. For shifting and balance at leaning postures, respectively, center of mass position and acceleration could be approximated to within 20% of the maximum value, with strong correlations (R>0.9) between values estimated by the proposed method and the true values derived from model dynamics. When utilizing the estimated feedback kinematics for FNS control, standing performance in terms of maximum upper extremity loading was still significantly reduced (p<0.001) compared to conventionally applying constant and maximal stimulation. In the future, these simulation-based methods will be employed to develop experimental approaches for restoring leaning standing function by FNS.

1 Introduction

Functional neuromuscular stimulation (FNS) is a proven clinical approach to restore basic standing and transfer capabilities following spinal cord injury (SCI) [1–3]. Individuals with SCI at thoracic levels can utilize electrical stimulation to elicit contractions of otherwise paralyzed musculature that extend the knees, hips and trunk to elevate from a seated position. While standing with continuous stimulation to stiffen the lower limbs, postural perturbations are resisted with the unaffected upper extremities since stimulation is typically applied without feedback. The users place their hands on a walker or a support surface to produce corrective loads that stiffen the torso to accommodate external disturbances [4]. The onus on the arms to execute balancing actions compromises the neuroprosthesis user’s ability to perform functional activities of daily living such as reaching and manipulating objects while standing. To address this limitation, feedback controllers have been tested and evaluated utilizing acceleration of total-body center of mass (CoM) to reduce the upper extremity (UE) loading needed to resist external disturbances in simulation [5–7] prior to laboratory implementation with neuroprosthesis users [4, 8] for maintaining balance at erect stance.

The next major advancement in standing neuroprosthesis functionality would be extending reaching capabilities for its users by effectively restoring and maintaining leaning postures. Current FNS systems only allow users to stand in one erect posture making it difficult or impossible to lean forward or to the sides without the potential of falling or collapsing. In order to minimize the onset of fatigue and to increase the ability to reach and perform manual functions, reduction of UE loading is a critical objective for improving functional performance with a standing neuroprosthesis [9]. Since maximizing standing reach entails whole-body leaning [10], neuroprosthesis users would require the ability to assume [11] and maintain balance at leaning postures with minimal UE loading. Successfully developing a standing neuroprosthesis requires sensor-based feedback control to reliably identify the desired leaning posture and outputting synergistic muscle excitation patterns that resist the measured disturbances about that setpoint posture.

This study investigated the potential of feedback control to minimize UE loading against postural disturbances in bipedal leaning postures by continuously adjusting stimulation levels for individuals with SCI. An FNS control system to maintain standing balance at various leaning postures was developed in simulation utilizing feedback of center of mass kinematics for displacement and acceleration in the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral dimensions. As previously in [6], inferior-superior kinematics were assumed sufficiently coupled to the other dimensions since typical standing is biomechanically resistant to collapse in that direction [12]. Simulation-based approaches are proven test-beds to develop a feasible strategy and determine the basic operating characteristics for proposed feedback controllers acting upon a three-dimensional musculoskeletal model of standing following SCI [7, 13] prior to laboratory experiments [4]. In this simulation study, we also evaluated using CoM-Acc and CoM-Pos as input signals for control of standing balance by FNS at leaning postures. This simulation environment allows us to assess how well these quantities could be estimated and then utilized from actual sensor signals. Recent advances have made available implanted sensors as part of a networked neuroprosthesis system (NNPS) developed at CWRU [14]. To investigate the potential of employing such a system in the laboratory for standing function, we present and test in simulation a novel methodology for estimating the desired feedbacks online from implantable sensors proposed for a networked neuroprosthesis system.

2 Methods

The overall model control system is shown in Figure 1A and involves two parallel control systems acting on a musculoskeletal model of stance. First, the volitional UE effort exerted by the user to stabilize against postural disturbances is represented by a feedback system to maintain shoulder position. Second, an FNS feedback controller was developed that modulates muscle excitation levels (analogous to stimulation levels in the model) to balance against postural perturbations while providing basic standing maintenance at a given setpoint posture.

Figure 1.

Simulation Model Structure - A) Flow diagram showns active control systems to maintain model posture at desired setpoint against balance perturbations. B) Equally-spaced center of mass locations for respective optimal postures projected onto target base of support area between feet (AP = anterior-posterior, ML = medial-lateral). Area divided into 6 regions with center location denoting desired respective setpoint. C) Schematic shows approximate location of implanted NNPS modules with accelerometer sensors (LEFT) and respective serial tilt model for estimating total-body center of mass kinematics from sensor signals (RIGHT).

Three-Dimensional Musculoskeletal Model of SCI Stance

A 3-D computer model of human bipedal stance following SCI was adapted from a previously described representation of the lower extremities [15] and trunk [16]. The model included nine segments (two feet, two thighs, two shanks, pelvis-lumbar component, and head-arm-trunk complex). The model had 12 anatomical degrees-of-freedom (DOFs) across the lower extremities: bilateral ankle plantar/dorsiflexion, ankle inversion/eversion, knee flexion/extension, hip internal external rotation, hip abduction/adduction, and hip flexion/extension. For the trunk, three additional DOFs were defined for a single joint at the lumbosacral transition (L5-S1). The muscle groups under active control were consistent with those targeted by an existing 16-channel implanted system [17] and identified as beneficial for transitioning to leaning postures [18]. This maximum muscle force parameters were scaled to reflect the effects of SCI according to procedures outlined in [5]. Each channel co-activated a respective group of muscles targeted for a particular clinical movement. Bilaterally, for each clinical movement, the corresponding muscles were: ankle plantarflexion (medial gastrocnemius, lateral gastrocnemius, peroneus longus), ankle dorsiflexion (tibialis anterior, peroneus tertius), knee extension (rectus femoris and vastus lateralis, medialis, intermedius), hip adduction (adductor magnus), hip abduction (gluteus medius), hip extension1 (gluteus maximus), hip extension2 (semimembranosus), and trunk extension (lumbar erector spinae). Synergistic muscle groups within parentheses share common innervations that can typically be activated with a single intramuscular electrode [12], and were assumed to be recruited and modulated simultaneously with one channel of stimulation. Two separate stimulation channels were utilized for hip extension due to its clinical importance to standing after paralysis and because gluteus maximus and semimembranosus are innervated separately. Passive joint moments that are typical following spinal cord injury were also included [19].

Representing Voluntary UE Actions

The UE loading a standing neuroprosthesis user may exert upon an assistive device or nearby support surface against perturbations to postural balance was represented by a PID (proportional-integral-derivative) controller for maintaining shoulder positions at the setpoint posture. The feedback gains were determined through Ziegler-Nichols tuning rules, and to approximate human operator response, 100ms pure time-delay and muscle force activation delay [20] were applied to the controller output forces applied to the shoulders as described in [5].

Development of FNS Feedback Controller

An FNS feedback controller for maintaining balance against external perturbations at leaning postures includes the following development steps: 1) Identify desired posture setpoints, 2) Compute baseline muscle activations and feasible changes in total-body center of mass acceleration (CoM-Acc) at each setpoint, 3) Create an artificial neural network (ANN) that relates optimal changes in muscle activations according to setpoint posture and changes in CoM-Acc, and 4) Create and tune a feedback control structure that drives each ANN to minimize the upper-extremity effort needed to stabilize against force-perturbations to posture. The muscle model used during forward simulations applies standard excitation-activation dynamics [20]. However, the optimization procedures utilized to develop the FNS feedback controller presumes muscle activations for identifying synergistic muscle actions to maintain standing balance in three dimensions. Functional standing performance is subsequently achieved across the muscle dynamics through tuning of the feedback gains [4, 5].

A two-tiered optimization procedure was utilized to determine postures, i.e., unique sets of joint angles, in relation to center of mass position (CoM-Pos) coordinates over the area between the feet (base of support, BoS) and the muscle activations to hold those postures. First, an optimization routine described in [18] solves for the joint angles for each posture CoM-Pos with coordinates in the anterior-posterior (AP) and medial-lateral (ML) dimensions serving as the optimization constraints. Nine rows of postures were equally spaced along each dimension, yielding a total of 81 test postures. The objective function was defined to minimize the joint angle deviations from neutral and maximizing the posture height. The second level of optimization solved for the muscle activations (0 = minimum, 1 = maximum) necessary to satisfy the constraints of the joint moments required to statically hold each posture against gravity, plus bias extension moments at the knees and hips [21] and trunk [5] to ensure stable standing following SCI. The objective function was a physiologically-based criterion to predict minimized muscle forces during locomotion [22].

In this study, the target BoS area was subdivided into six regions (Figure 1B). Each region encompassed three rows of postures in the ML-dimension. The three back regions (1,2,3) and three forward regions (4,5,6) encompassed four and five rows of postures in the AP-dimension, respectively. The setpoint of each region is the posture associated with the position most central, according to CoM AP and ML-coordinates, within each region. The “baseline” muscle activations for each setpoint were computed from a weighted-average of muscle activation data across all postures in that region but proportionally weighted more towards those located closer to the setpoint. The furthest posture was weighted by zero, and each posture (index = ‘p’) has weighting factor (W) relative to that reference distance (dmax) and the number of postures (np) in that region as follows:

| (1) |

This weighted approach was employed to consider variable effects of constant bias moments for varying postures across the entire region.

An artificial neural network for relating optimal CoM-Acc values for a given posture location to changes in muscle activation level was created and trained according to procedures originally described in [6]. In this study, the single ANN included inputs for CoM-Acc and CoM-Pos coordinates that generally defined the posture location. The trained ANN utilizes the CoM-Pos to sufficiently approximate the current posture and the CoM-Acc inputs produce the changes in muscle activations necessary to resist perturbation effects about that presumed posture. The ANN included three layers (input, hidden, output) with feedforward architecture. Additional details for ANN training can be found in [6]. For a single training point in this study, each unique set of CoM-Acc and CoM-Pos values served as the ANN inputs, and the corresponding muscle activation levels served as the ANN outputs. These training data were created in a stepwise manner as follows:

First, the CoM-Acc values induced in the AP- and ML-dimensions (aCOM-AP, aCOM-ML) by each stimulated muscle group (index = ‘m’) for each optimal posture with unique CoM-Pos coordinates following a maximum increase in activation from baseline for that muscle group, ΔMmax,m = 1 - Mbase,m, were recorded. These acceleration values were computed from model system equations of motion (SD/FAST, Symbolic Dynamics, Inc., Mountain View, CA) with zero initial velocity and acceleration for all skeletal states.

Second, feasible CoM-Acc targets (ACCAP, ACCML) were identified about each posture. The maximum target value in each direction (forward, backward, right, left) was determined by summing the aCOM values unique to that direction for all muscle groups. Within these maximum target values, a thousand equally distributed CoM-Acc targets were specified.

Third, an optimization routine was applied to determine muscle activation levels (Mm) to meet these CoM-Acc targets according to the objective function for muscle force prediction in locomotion from [22] and the following constraint equations for each target:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ‘nm’ is the total number of muscles and xm is the solution activation for muscle ‘m’ bounded over [0,1]. Target solutions were deemed feasible if both constraint equations were met within tolerance of 0.01 m/s2. Additional parameters for the optimization can be found in [6]. The solution elements are converted to muscle activation levels as follows:

| (4) |

Perturbation Simulations

A total of 40 perturbation simulations were specified, in each of which a single force-pulse perturbation was applied on any one of five segments (thorax, lumbar spine, pelvis, right thigh, right shank) in any one of eight directions (forward, forward-rightward, rightward, backward- rightward, backward, backward-leftward, leftward, and forward-leftward). The five segments chosen effectively spanned the entire model. Each forward simulation to test standing performance against a balance disturbance was carried out over two seconds in simulation time with time-sampling at 100Hz. From time (t) 0.0 to 1.0 sec, the model achieved a steady-state posture in accordance to the forces applied from muscle activations, passive joint properties, and upper-extremities about the desired setpoint. At t = 1sec, a force-pulse (amplitude: 15% model body-weight, duration: 200msec) was applied to a single segment. From t = 1.0 to 2.0 sec, the model control systems act to resist the perturbation. Model performance to resist the disturbance was measured according to the total upper-extremity loading that was applied during the force-pulse plus a subsequent recovery period of 0.5 seconds (i.e., t = 1.0 to 1.7sec). The recovery period was sufficient for the model to apply < 25% the maximum loading value for every simulation.

Shifting Simulations

Simulations for shifting the model from erect to a leaning posture were not evaluated for upper-extremity performance, but rather to examine the potential robustness of estimating center of mass kinematics for posture shifting applications [11, 18]. Each shifting simulation occurred over 2.0 seconds with the model posture initially consistent with the region 2 setpoint for t = 0.0 to 1.0 sec. The upper-extremity setpoints would then linearly displace starting at t = 1.0 sec with a magnitude of 10 cm over t = 1.0 to 2.0 sec in one of five directions: forward, rightward, leftward, forward-rightward, and forward-leftward.

Tuning FNS Feedback Controller

For each region setpoint, optimal feedback gains were determined that minimized the upper-extremity loading exerted to stabilize the model during the perturbation and recovery periods across all 40 perturbation simulations [23]. Each feedback gain pre-multiplied a respective component of CoM-Acc prior to input to the artificial neural network. Two optimal gains were determined for the AP-dimension, one for each direction. A single gain was identified for the ML-component of CoM-Acc given the symmetry of muscle activation solutions along that dimension. Each CoM-Pos input was pre-multiplied by unity assuming CoM-Pos changes about the setpoint are relatively minimal during perturbation trials.

Estimating Center of Mass Kinematics for Feedback Control from Implanted Sensor System

To test the potential feasibility of utilizing the implanted sensing capabilities of a new networked neuroprosthesis system [14] for control of standing, a method to estimate CoM-Pos and CoM-Acc feedbacks from the implanted modules was tested and evaluated in simulation. The NNPS offers a flexible, modular architecture for restoring function by FNS and includes an implanted power control module remotely connected to small, remote stimulation and biopotential sensing modules distributed throughout the body. One possible NNPS configuration for restoring advanced standing function is shown in Figure 1C (LEFT). The power module would be located just above the anterior pelvic brim. Two stimulation modules would be located bilaterally near the midpoint of a line connecting the respective hip joint center to pubis midline. These modules would activate quadriceps musculature for knee extension. Two stimulation modules would be located bilaterally between the respective 12th rib and pelvis within the lateral radial quadrant. These modules would activate erector spinae, gluteus maximus, and gluteus medius musculature to control the hips and lower back. One stimulation module would also be located on the lower third of each thigh on the posterior side above the knees between the hamstring tendons. Both of these modules would activate dorsi- and plantar-flexor musculature for ankle control. Finally, two sensor-only modules may be implanted in the upper anterior portion of the torso for tracking upper-body kinematics that notably contributes to total-body center of mass during standing [4]. Every module contains a tri-axial accelerometer (Kionex, KXTE9, ±2g). Three-dimensional accelerometer signals were then simulated at the defined point-locations for each of the modules, which were presumed to be rigidly affixed to the nearest segment identified in our model as follows:

First, the acceleration due to gravity was added to the three-dimensional linear acceleration of the point-location for each sensor.

Second, this net acceleration was then transformed to be expressed in the local segment/sensor coordinate system.

Third, white noise (0.2 m/s2 peak-to-peak) and slow moving offset (2 Hz sine wave, 0.1 m/s2 amplitude) were added to each acceleration signal component as is typical with real-world accelerometers [24].

The key operating principle in our estimation of both CoM-Pos and CoM-Acc from only accelerometers was that each accelerometer signal was assumed to represent either induced linear accelerations to update CoM-Acc or the tilt/orientation of the affixed segments to update CoM-Pos at each time-instant. Without such an a priori assumption, it is not possible to absolutely attribute the source cause (i.e., induced acceleration or change in orientation by which acceleration to gravity newly represents itself) to change in accelerometer signal. It was generally specified that if the accelerometer signal magnitude was above a particular threshold value, the former case of induced acceleration applied. If below, the latter case of changing orientation applied. Total-body center of mass kinematics were estimated assuming a simplified 4-segment serial tilt-model to represent the standing system (Figure 1C, RIGHT). Each segment represented a mass (Massseg) and a length (Lengthseg) from its base to its center of mass location consistent with its anatomical counterparts in our 3-D model of stance. The signals of sensors presumed affixed to the same segment were averaged to yield a single 3-D accelerometer signal for the entire segment. When all segmental tilt angles were zero, the local segment coordinate system expressing the accelerometer signal was presumed to be aligned with a globally-fixed anatomical reference frame with axis conventions of X+=anterior, Y+=superior, Z+=rightward and acceleration due to gravity (g, 9.81m/s2) in the −Y direction.

Each segment was presumed to be serially connected away from ground at endpoints via universal joints with two DOFs representing two non-zero angles of tilt about the AP- and ML- axis. When linear acceleration changes were assumed to be sufficiently small relative to g, the tilt angles (ϕ,θ,Ψ) representing the segment rotations relative to the global frame were computed from the segment 3-D accelerometer signal (AX, AY, AZ) as follows [20]:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

The θ angle was assumed to be zero since it initially represents rotation about the axis aligned with gravity and cannot be uniquely solved. Figure 1C explicitly indicates the positive directions of rotation relative to the global standing reference frame.

If the instantaneous derivative (central-difference method) of the accelerometer signal magnitude was less than a threshold of 5m/s3, the change in signal was presumed to be due to change in orientation of the segment reference frame relative to the global frame. The threshold- value was selected based on heuristic observation. Tilt angles were then computed and averaged from the ten previous time-instances that satisfied this below-threshold criterion. Assuming θ equal to zero and Z-X-Y rotation order, the remaining two tilt angles were utilized to compute a segment reference frame relative to global as follows:

| (8) |

When the magnitude-derivative of the accelerometer signal was greater than 5m/s3, changes in acceleration were then presumed to be due to induced linear changes in acceleration while the orientation of the accelerometer was held constant at the previously established segment reference frame.

Finally, the estimated total-body center of mass (CoM) acceleration with respect to the presumed global reference frame while removing effects of gravity was using standard computations for center of mass [25, 26] and reference frame transformations [27]:

| (9) |

The estimated total-body center of mass position/displacement from an initially erect posture was solved from:

| (10) |

| (11) |

Testing Balance Performance for Different Stimulation Modes

The ability of the model to maintain balance against postural perturbations at each region setpoint was assessed for four different stimulation modes defined in simulation to represent potential real-world performance as follows:

To simulate the typical clinical case of maximal, constant stimulation for erect standing by FNS [1], all muscle groups targeted for stimulation were maximally activated except the ankle plantar-flexors, which were adjusted to 0.26 activation for erect standing as in [5]. This stimulation mode was the ‘Maximal’ case.

Constantly applying the optimal baseline activation levels corresponding to the optimal setpoint posture was the ‘Base’ case.

Applying the muscle excitation levels that were modulated due to FNS control utilizing ideal feedback of center of mass position and acceleration about the desired setpoint was the ‘Controller’ case.

The ‘NNPS’ stimulation mode was applied when feedback control utilized center of mass kinematics estimated from simulated NNPS sensor signals, but with the same feedback gain values optimized for ‘Controller’.

Statistical Analyses

Although computer simulations produce deterministic results, statistical comparisons were made between stimulation modes or between regions on the basis of variable responses across perturbation locations and directions and position of model within each region. All statistical comparisons for performance between stimulation modes or mean data values between regions were performed utilizing a paired t-test. Normality of sample distributions was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For comparison between stimulation modes, each perturbation simulation served as an individual trial sample. Comparing regional data values was based on 20×20 sampling of mesh points within each region.

3 Results

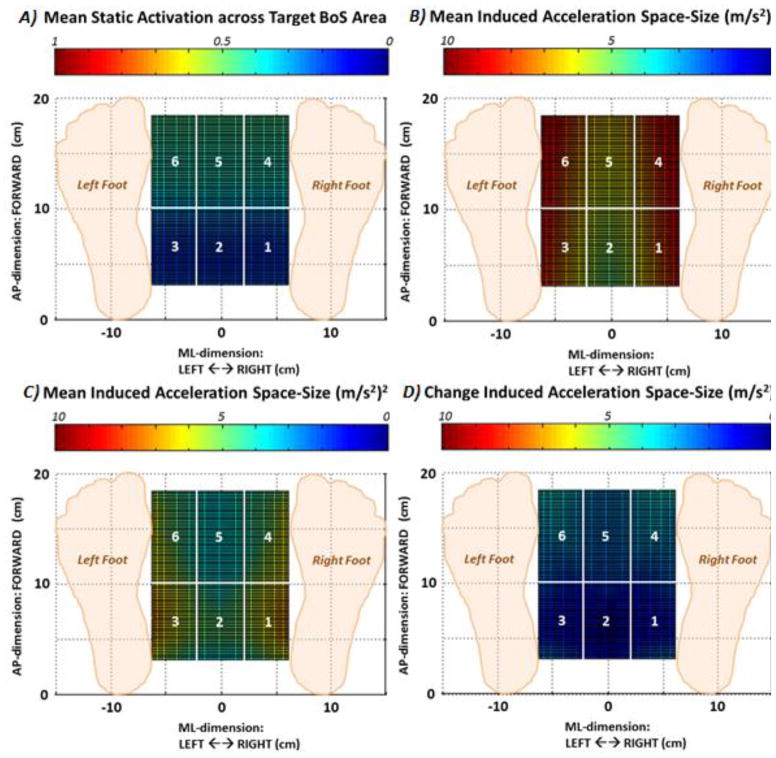

The data utilized to develop the simulated FNS controller are represented as mesh-functions of standing center of mass position over the base of support in Figure 2. The mean base activation level across all 16 SCI-adjusted muscle groups targeted for stimulation during the task of optimal static standing maintenance is shown in Figure 2A. There was a significant increase (p<0.001) in the baseline muscle activation level necessary to hold postures that were leaning forward (0.417 for regions 4,5,6; Table 1) compared to those that were more erect (0.217 for regions 1,2,3; Table 1). There was no significant difference (p>0.05) in mean activation level between central regions (0.316 for regions 2 and 5) compared to those involving leans to either side (0.316 for regions 1,3,4,6). The effects of tasking the muscles for static standing at various leaning postures on the magnitude of accelerations (2-D area, (m/s2)2) that can then be induced for resisting disturbances are shown across Figure 2B (no static activations), Figure 2C (static activations present), and Figure 2D (difference in acceleration magnitudes due to presence of static activations). For all 6 regions, the reduction in acceleration magnitude due to static activations was significantly greater (39% versus 20%, p<0.001) for the forward leaning regions (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Muscle activation and induced acceleration data meshed as a function of location of center of mass projection within target base of support area and used to construct FNS feedback controller. A) Mean of baseline muscle activation levels needed to statically hold model at respective optimal posture against gravity, B) Area magnitude across anterior-posterior (AP) and medial-lateral (ML) dimensions of acceleration of model center of mass (CoM) that can be maximally induced with no (zero) static muscle activations present, C) Area acceleration magnitude of CoM acceleration assuming non-zero static muscle activations are present, D) Differential change in magnitude of CoM acceleration due to presence static muscle activations.

Table 1.

Muscle activation and induced acceleration data used to create feedback controller for each region defined within target base of support area

| Region 1/3 | Region 2 | Region 4/6 | Region 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Muscle Activation | 0.217 ± 0.042 | 0.217 ± 0.045 | 0.416 ±0.032 | 0.416 ±0.031 |

| Induced Acceleration Magnitude with no Static Activations (m/s2)2 | 7.40 ±0.85 | 5.48 ±0.32 | 7.97 ± 0.74 | 6.36 ±0.30 |

| Induced Acceleration Magnitude with Static Activations (m/s2)2 | 5.84 ± 0.72 | 4.43 ± 042 | 4.98 ±0.64 | 3.77 ± 0.15 |

| Δ Induced Acceleration (m/s2)2 (% Change) | 1.55 ±0.40 (21.0%,***) | 1.05 ±0.52 (19.2%,***) | 2.99 ±0.44 (37.5%,***) | 2.58 ±0.18 (40.6%,***) |

Note(s): %Change = Percentage Change in Acceleration Magnitude due to Presence of Static Activations,

= p < 0.001 for non-zero value

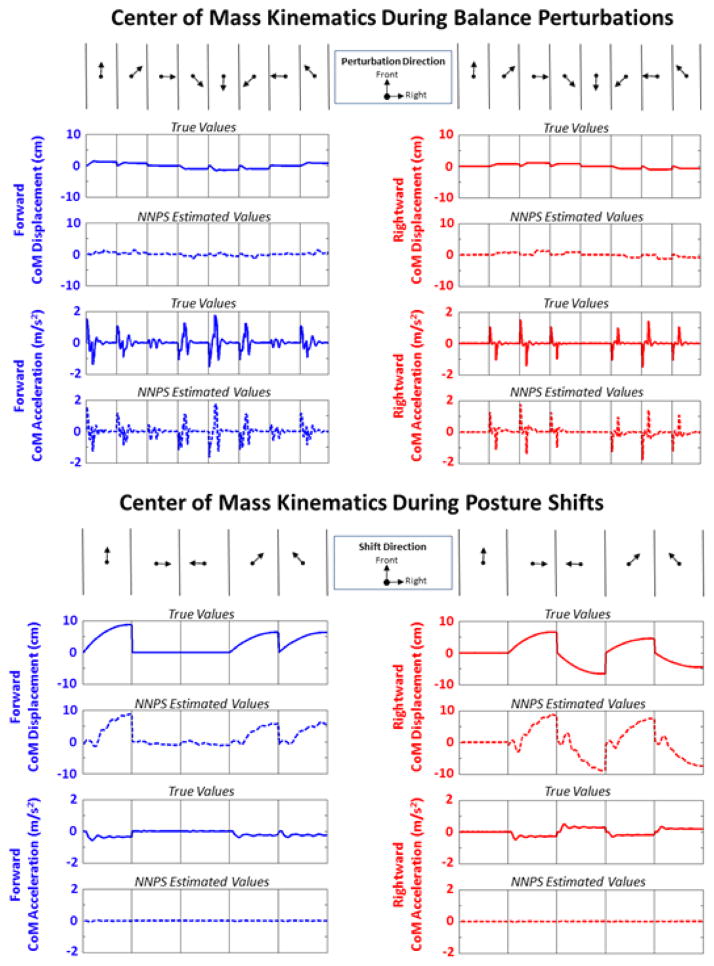

Kinematic trajectories of the center of mass in the AP and ML dimensions to be estimated and utilized for feedback control for advanced FNS standing function during balance perturbation and shifting simulations are presented in Figure 3. Utilizing the simulated results of the proposed NNPS to estimate CoM position, presented as displacement from erect, and CoM acceleration clearly captured the bursting accelerations during perturbations and rising displacements during posture-shifts. High correlation results (R>0.90, see Table 2) between actual and estimated values for displacement and acceleration were observed for shifting and perturbation simulations, respectively. The relative error (%max) was less than 20% for these particular data as well. A sensitivity analysis about the selected sensor locations demonstrated that estimation performance during perturbation and shifting simulations resulted in <0.01%/cm reduction in estimation accuracy.

Figure 3.

True and NNPS estimate of center of mass kinematics incurred in anterior-posterior and medial-lateral dimensions expressed in the forward, rightward directions, respectively, during either perturbations (thorax, region 2 setpoint) or posture shifts from region 2.

Table 2.

Errors in NNPS estimate of center of mass (CoM) kinematics utilized for feedback control

| POSTURE SHIFTING | BALANCE PERTURBATIONS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | Estimation Error | Error (%Max) | R | Mean Value | Estimation Error | Error (%Max) | R | |

| CoM Displacement –Forward (cm) | 2.91 ±2.96 | 1.12 ± 1.03 | 12.9% | 0.94 | 0.71 ±0.49 | 0.46 ±0.39 | 33.3% | 0.75 |

| CoM Displacement – Rightward (cm) | 3.10 ± 2.27 | 1.39 ± 1.30 | 19.1% | 0.92 | 0.55 ±0.40 | 0.21 ±0.28 | 21.2% | 0.86 |

| CoM Acceleration –Forward (m/s2) | 0.165 ± 0.154 | 0.160 ± 0.149 | 27.7% | 0.52 | 0.202 ± 0.327 | 0.084 ±0.106 | 4.8% | 0.94 |

| CoM Acceleration –Rightward (m/s2) | 0.185 ± 0.122 | 0.182 ± 0.120 | 37.2% | 0.47 | 0.089 ± 0.249 | 0.067 ±0.088 | 4.4% | 0.93 |

Note(s): Mean Value = Mean absolute value across all data trajectories, %Max = mean estimation error divided by maximum value to be estimated* 100, ‘R’ = Pearson’s correlation coefficient

The total upper-extremity (UE) loading, sum of 3-D magnitude for right and left side, results from a sample perturbation simulation are shown for each of the four stimulation modes in Figure 4. The maximum UE loading, universally incurred during the perturbation period, for both feedback cases (Controller, NNPS) was less than both constant stimulation cases (Maximum, Base). Over the course of the recovery period, the feedback control cases appear to more effectively dampen the oscillatory UE loading response.

Figure 4.

Upper-extremity loading to stabilize model during single perturbation trials for each of four muscle functional neuromuscular stimulation modes: 1) Constant “Maximum”, 2) Constant “Base”, 3) Feedback “Control”, and 4) “NNPS” Feedback Control. Perturbation applied as force pulse (amplitude: 15% body- weight= 114N, duration: 0.2 seconds) in forward direction at thorax.

The mean and maximum UE loading responses as a function of direction are shown in Figure 5. All results are normalized to those of the Maximum case, which self-normalized converts to a unit circle, to compare performance of each stimulation mode relative to the clinical standard. For forward leaning setpoints (regions 4,5,6), notable additional mean UE loading (Figure 5, TOP) must be applied to displace the model away from erect for the Maximum case. Therefore, the relative mean UE loading exerted for the other three cases that produce optimal baseline activation levels during quiet standing was notably lower than Maximum for those setpoints. For the more erect setpoints (regions 1,2,3), the optimal stimulation cases appear more effective in resisting forward perturbations and perform similarly as the Maximum case for backward perturbations. For regions 1 and 3 which involve leaning rightward and leftward respectively, it appears greater relative mean UE effort was required for the optimal stimulation cases when disturbances were applied in directions towards the side of the support-leg. For example, increased relative effort for rightward disturbances were observed when leaning right, i.e., region 1 setpoint.

Figure 5.

Overall upper-extremity loading results binned across perturbation direction (F = forward, B = Backward, R = Rightward, L = Leftward) for each of four stimulation modes. All results are normalized to be “relative” to the constant maximum stimulation case. The mean and maximum upper-extremity loading results are tabulated over perturbation plus recovery periods across all perturbation simulations.

For relative maximum UE loading (Figure 5, BOTTOM), the differentials between the three optimal stimulation cases versus the Maximum case were smaller compared to mean UE loading. For backward disturbances, the Base case performed worse than the Maximum case. However, the presence of feedback control (Controller or NNPS cases) universally outperformed either constant stimulation case in every direction for all six setpoints. The Controller case utilizing true values of CoM kinematics for feedback universally outperformed the NNPS case utilizing estimated values from simulated accelerometer signals.

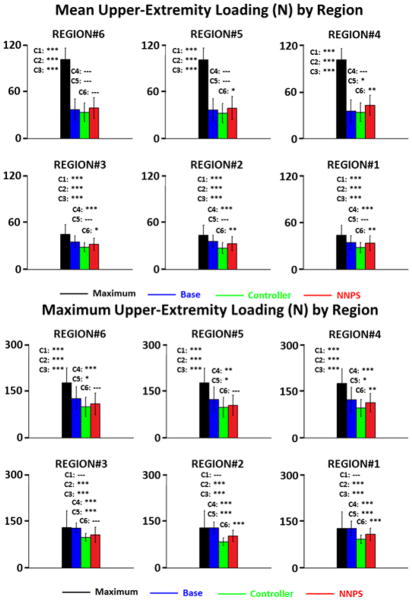

The mean and maximum UE loading results are binned by region in Figure 6. Mean UE loading was significantly greater (p<0.001) than any of the optimal stimulation cases. Maximum UE loading was also significantly greater (p<0.001) for the Maximum case compared to the optimal stimulation cases (comparisons C1,C2,C3) except for the more erect setpoints (regions 1,2,3) and only when compared to Base (C3), the other constant stimulation case. The Controller case outperformed either Base or NNPS for every comparison (C4, C6), but the performance differential was not always significant. The Controller did significantly outperform (p<0.05) the other two optimal stimulation cases for the more erect setpoints except when compared to the NNPS case (C6) for the metric of maximum UE loading at the region 3 setpoint where no significant difference (p>0.05) was observed. The NNPS case significantly outperformed (p<0.05) the Baseline case (C5) for maximum UE loading at every setpoint, but for mean UE loading, no significant differences were observed between the two cases except at region 4.

Figure 6.

Mean and maximum upper-extremity loading across regions for each of four stimulation modes during perturbation plus recovery periods. Note(s): Six comparisons (C) for statistical differences between stimulation modes (bars) are made. Above each bar, from top-to-bottom, comparisons are made between mode of given bar and modes of bars progressively to right. Note: *** is p<0.001, ** is p<0.01, * is p<0.05, -- is p≥0.05

4 Discussion

This study presents methodology and results using a 3-D computer model of standing to investigate the potential of restoring leaning postures with FNS following SCI. The results indicated that a control paradigm outputting optimal stimulation patterns according to feedback of center of mass kinematics can notably outperform the conventional usage of constant supramaximal stimulation, even at leaning postures and presuming the performance limitations of current sensor technology. Across a variety of leaning standing postures with center of mass positions uniquely located over a target base of support, feedback control reduced the upper extremity loading necessary for stabilization following balance perturbations. While the Base case of using constant but optimal, submaximal stimulation levels did outperform the Maximal case in several instances for the mean UE loading exerted, the Controller case was universally superior to the Maximal case regardless of perturbation direction or setpoint location. This observation suggests that applying optimal, even if constant, stimulation levels according to the center of mass location of the desired leaning setpoint posture can produce benefits over conventional maximal stimulation. However, feedback control utilizing center of mass acceleration provides added value for stabilization, especially in reducing the peak UE loading.

Ultimately, UE loading provides a standing performance metric that indicates the level of volitional interaction with the environment needed to stabilize beyond the actions of the FNS feedback controller. Our model presumes the feet are effectively fixed to the ground and that forces at the shoulders are similar to those measured at the hands interacting with a support device or surface. These assumptions are consistent with laboratory observations of neuroprosthesis users under moderate external perturbations invoking small postural kinematic changes when standing with both arms on an assistive device [4, 28]. Also consistent with laboratory observations, simulation results expectedly show upper-extremity loading move towards zero with return to the desired setpoint following initial resistance and recovery from the external perturbation. Recent implant recipients often achieve effectively erect standing whereby more than 90% of body-weight are through the feet for prolonged quiet standing on average, and only light touch was needed for balance [29].

While the benefits of feedback control are apparent even for forward leaning postures, the improvement in performance with feedback control is notably mitigated in these cases given the greater baseline muscle activations that are necessary to hold these postures against gravity. As such, there is an inherent and expectant trade-off in the ability to resist disturbances with greater leaning. Nonetheless, it appears that even with muscle forces typical of SCI, considerable forward lean within the base of support is possible and more stable with feedback control. For laboratory experimentation, the acceptable magnitude of lean versus attainable stability will be predicated on the stimulated muscle forces that can be generated for each particular individual.

Although the presented results are based in simulation, they provide important insight into the feasibility and how to approach development of FNS feedback control to restore leaning standing function. These methods utilized for controller development in simulation may either be analogously replicated experimentally or used to produce a first-approximate controller in simulation with select subject-specific characteristics and then ported experimentally for subsequent tuning. Potentially, model-based methods could be validated and subsequently utilized for parameter identification of individual components of the physiological system [25]. For larger scale system analysis, simulation results can estimate metrics such as skeletal loading that cannot otherwise be readily measured in vivo [27] or provide important insights into the basic operating characteristics of a proposed control system posing constraints similar to those expected to be observed in the clinical setting [5]. In this study, the input-output mapping represented by the ANN is predicated mainly on the specific muscles targeted for stimulation and their respective force generating capacities to produce desired kinematic profiles of the model’s total-body center of mass. Similar techniques may be developed to construct an FNS controller mapping to restore standing balance in the laboratory for a particular subject at leaning postures as has already been previously accomplished for the erect standing posture [4]. However, the ability to effectively exploit that mapping may depend on the robustness of the feedback variables driving the control structure.

It has been previously shown in simulation the advantages of center of mass acceleration over comprehensive joint-based control given typical sensor errors and the number of sensors to be necessarily deployed [7]. While some postural information is lost when utilizing a simplified representation of the standing system such as total-body center of mass, such a variable can effectively be exploited for FNS feedback control due to the stereotypical features of standing. Essential control principles have previously been elucidated by assuming simplifying approximations of standing such as an inverted pendulum [30, 31] or identifying distinct ankle and hip strategies for balance control [32]. In this study, target center of mass variables for feedback were estimated by representing the standing system as a simplified serial linkage of cylinders. Although we applied FNS control to an anatomically realistic model of standing, the simplified representation for feedback estimation produced sufficiently robust results to effectively drive feedback control using the proposed NNPS sensor set. Feedback estimation being insensitive to sensor locations upon respective segments indicates segment orientation dynamics were small for these standing simulations. In the future, methodological parameters such as signal-derivative threshold equal to 5m/s3 or ten time-samples being used to compute segment orientation may be optimized to further improve estimation. Overall, this investigation still demonstrates the potential for improved standing neuroprosthesis performance at leaning postures using novel feedback estimation of center of mass kinematics expected with a currently available sensor-based system.

In testing UE loading performance for the NNPS case, the same feedback gains that were optimally tuned assuming perfect feedback estimation were retained to focally identify the potential degradation in simulated performance due to feedback error while keeping all other simulation conditions constant. However, it is likely that performance of the NNPS case would have further approached that of the Controller case if gains were specifically re-tuned according to NNPS feedback. During laboratory testing, feedback gains can also be tuned to improve performance in the presence of modest errors in feedback estimation. Laboratory tuning is necessary to optimize neuroprosthesis performance with a particular subject, but the process can be time-intensive. For testing additional leaning postures, it may be necessary to provide the subject visual feedback to ensure that the desired leaning posture has been approximately assumed. Visual feedback of a particular torso position or force-plate tracking of center of pressure location prior to application of disturbances may facilitate this calibration. As such, approaches which aim to streamline tuning procedures [28, 33] are valuable to improve convergence upon optimal parameters for multiple functions. A simulation-based approach may be especially valuable, if not necessary, in producing a control structure in the laboratory that aims to restore function at multiple postural setpoints.

Simulations may also better facilitate the development of control schemes that consider the effects of muscle fatigue [34]. The current study assumed typical muscle force generation following SCI [5] and related previous experimental work assumed minimal fatigue relative to previous measurements [4, 8]. These studies establish the feasibility of three-dimensional and synergistic balance control following SCI, but optimizing clinical performance would entail establishment of novel methods for controller adaptation [33]. The methods outlined in this study may be configured to consider fatigue by creating additional ANN mappings that represent fatigued states, adapting the ANN with new data points relating stimulation and CoM kinematics, or re-optimizing feedback gain values. In any case, fatigue can be expected to reduce the general capacity to reject postural disturbances.

5 Conclusions

Ultimately, tuning the FNS standing control system according to the objective criterion of minimal upper extremity loading remains a fruitful and productive approach, even for leaning setpoint postures. This simulation study indicates that upper extremity loading may be reduced with control of muscle stimulation levels using feedback of total-body center of mass kinematics that relies on current sensor-based technology. While hands-free FNS standing is the theoretical ideal, notable technological barriers still exist in comprehensively identifying the standing system for each subject and actuating muscle forces with large magnitude and minimal variability. Minimizing upper extremity loading does not eliminate pursuit of hands-free standing, but rather provide an appropriate pathway that promotes active progress with current resources and can readily adapt with further technological breakthroughs. Future testing will involve building upon the presented simulation-based methods in the laboratory and include developing experimental paradigms of leaning and performing functional reaching tasks with one arm while the other provides minimal support.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01NS040547 from NINDS/NIH, and T32AR00750525 from NIAMS/NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAMS or NIH. The research described here was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service - Award No. A9259-L. The research was approved by VA IRB #2008-027.

References

- 1.Davis JA, Jr, et al. Preliminary performance of a surgically implanted neuroprosthesis for standing and transfers--where do we stand? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38(6):609–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jovic J, et al. Coordinating Upper and Lower Body During FES-Assisted Transfers in Persons With Spinal Cord Injury in Order to Reduce Arm Support. Neuromodulation. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ner.12286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch CL, Popovic MR. A comparison of closed-loop control algorithms for regulating electrically stimulated knee movements in individuals with spinal cord injury. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2012;20(4):539–48. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2185065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nataraj R, Audu ML, Triolo RJ. Center of mass acceleration feedback control of standing balance by functional neuromuscular stimulation against external postural perturbations. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60(1):10–9. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2218601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nataraj R, et al. Comprehensive joint feedback control for standing by functional neuromuscular stimulation-a simulation study. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2010;18(6):646–57. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2010.2083693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nataraj R, et al. Center of mass acceleration feedback control for standing by functional neuromuscular stimulation: a simulation study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(2):279–96. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2010.12.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nataraj R, Audu ML, Triolo RJ. Comparing joint kinematics and center of mass acceleration as feedback for control of standing balance by functional neuromuscular stimulation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nataraj R, Audu ML, Triolo RJ. Center of mass acceleration feedback control of functional neuromuscular stimulation for standing in presence of internal postural perturbations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(6):889–911. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2011.07.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhlir JP, Triolo RJ, Kobetic R. The use of selective electrical stimulation of the quadriceps to improve standing function in paraplegia. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng. 2000;8(4):514–22. doi: 10.1109/86.895955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavanaugh JT, et al. Kinematic characterization of standing reach: comparison of younger vs. older subjects. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1999;14(4):271–9. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audu ML, et al. Posture shifting after spinal cord injury using functional neuromuscular stimulation--a computer simulation study. J Biomech. 2011;44(9):1639–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo AD, Zajac FE. A biomechanical analysis of muscle strength as a limiting factor in standing posture. J Biomech. 1993;26(Suppl 1):137–50. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90085-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JY, Popovic MR, Mills JK. Dynamic modeling and torque estimation of FES-assisted arm-free standing for paraplegics. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006;14(1):46–54. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.870489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peckham PH. Neuromodulation: Implantable Neural Stimulators. Elsevier Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao W, et al. A bipedal, closed-chain dynamic model of the human lower extremities and pelvis for simulation-based development of standing and mobility neuroprostheses. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Socieity, 1998. Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 1998; Hong Kong, China.. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambrecht JM, et al. Musculoskeletal model of trunk and hips for development of seated-posture-control neuroprosthesis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(4):515–28. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.08.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhadra N, Kilgore KL, Peckham PH. Implanted stimulators for restoration of function in spinal cord injury. Med Eng Phys. 2001;23(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(01)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audu ML, et al. Posture-dependent control of stimulation in standing neuroprosthesis: simulation feasibility study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(3):481–96. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.06.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amankwah K, Triolo RJ, Kirsch R. Effects of spinal cord injury on lower-limb passive joint moments revealed through a nonlinear viscoelastic model. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(1):15–32. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.01.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zajac FE. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1989;17(4):359–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagaya H, et al. Ankle, knee, and hip moments during standing with and without joint contractures: simulation study for functional electrical stimulation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;77(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199801000-00009. quiz 65–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowninshield RD, Brand RA. A physiologically based criterion of muscle force prediction in locomotion. J Biomech. 1981;14(11):793–801. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(81)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray GA, Golda TG. Algorithm 856: APPSPACK 4.0: Asynchronous parallel pattern search for derivative-free optimization. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 2006;32:12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luinge HJ, Veltink PH. Inclination measurement of human movement using a 3-D accelerometer with autocalibration. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2004;12(1):112–21. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2003.822759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter DA. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eames M, Cosgrove A, Baker R. Comparing methods of estimating the total body centre of mass in three-dimensions in normal and pathological gaits. Human Movement Science. 1999;18(5):637–646. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig JJ. Introduction to robotics: mechanics and control. Vol. 3. Pearson Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nataraj R. Biomedical Engineering. Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH, USA: 2011. Feedback Control of Standing Balance Using Functional Neuromuscular Stimulation Following Spinal Cord Injury; p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho CH, et al. Functional electrical stimulation and spinal cord injury. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2014;25(3):631–654. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rietdyk S, et al. NACOB presentation CSB New Investigator Award. Balance recovery from medio-lateral perturbations of the upper body during standing. North American Congress on Biomechanics. J Biomech. 1999;32(11):1149–58. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winter DA, et al. Stiffness control of balance in quiet standing. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(3):1211–21. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55(6):1369–81. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nataraj R, Audu ML, Triolo RJ. Modified Newton-Raphson method to tune feedback gains of control system for standing by functional neuromuscular stimulation following spinal cord injury. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2014;11(4):169–174. doi: 10.3233/ABB-140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riess J, Abbas JJ. Adaptive control of cyclic movements as muscles fatigue using functional neuromuscular stimulation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2001;9(3):326–30. doi: 10.1109/7333.948462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]