Abstract

Purpose

The T790M gatekeeper mutation in the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is acquired by some EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) as they become resistant to selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). As third generation EGFR TKIs that overcome T790M-associated resistance become available, noninvasive approaches to T790M detection will become critical to guide management.

Experimental Design

As part of a multi-institutional Stand-Up-To-Cancer collaboration, we performed an exploratory analysis of 40 patients with EGFR-mutant tumors progressing on EGFR TKI therapy. We compared the T790M genotype from tumor biopsies with analysis of simultaneously collected circulating tumor cells (CTC) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).

Results

T790M genotypes were successfully obtained in 30 (75%) tumor biopsies, 28 (70%) CTC samples and 32 (80%) ctDNA samples. The resistance-associated mutation was detected in 47–50% of patients using each of the genotyping assays, with concordance among them ranging from 57–74%. While CTC- and ctDNA-based genotyping were each unsuccessful in 20–30% of cases, the two assays together enabled genotyping in all patients with an available blood sample, and they identified the T790M mutation in 14 (35%) patients in whom the concurrent biopsy was negative or indeterminate.

Conclusion

Discordant genotypes between tumor biopsy and blood-based analyses may result from technological differences, as well as sampling different tumor cell populations. The use of complementary approaches may provide the most complete assessment of each patient’s cancer, which should be validated in predicting response to T790M-targeted inhibitors.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA, EGFR, T790M, lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring activating mutations in the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) demonstrate significant progression-free survival benefit when treated with EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) (1). However, the vast majority acquire resistance after 12–24 months of treatment (2–4). Serial tumor biopsies, autopsy studies, and preclinical modeling experiments have defined multiple pathways by which EGFR-mutant NSCLC develop TKI resistance. These include acquisition of the recurrent T790M “gatekeeper” mutation which reduces 1st-generation EGFR inhibitor binding, amplification of signaling molecules that bypass the EGFR inhibition (MET, HER2), mutations in other genes that may substitute as oncogenic drivers (PIK3CA, B-RAF) (5–9), Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), and conversion to small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (10,11). T790M accounts for over half of resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib, and the recent development of covalently binding, irreversible inhibitors that effectively target T790M (3rd-generation EGFR TKIs) presents an urgent need for methods to identify this mutation (12,13).

Repeat tumor biopsies from patients with acquired resistance were initially obtained through research efforts to ascertain mechanisms of resistance (5,6) but are now recommended in NCCN guidelines to help select second-line therapies (14). However, such biopsies are associated with both risk and discomfort and may not always supply enough tumor tissue for genetic analyses. Moreover, in patients with multiple metastases, which may be heterogeneous with respect to their acquired mutations, selection of a single site for biopsy may not provide a representative profile of the overall predominant resistance mechanisms within the patient (15). Hence the ability to test for the T790M mutation through blood-based sampling may provide valuable clinical information, noninvasively obtained and representative of multiple tumor sites, and thus help identify patients most appropriate for T790M-targeted 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs.

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) are shed by primary and metastatic tumors into the vasculature and may serve as a source of cancer cells for genotype analysis. In patients with EGFR mutant NSCLC with high numbers of CTCs, we have previously shown that an allele-specific assay can detect the emergence of T790M during first-line therapy (16). More sensitive microfluidic CTC capture technologies (17) combined with more sensitive genotyping assays are now poised to provide a robust approach for CTC-based genotyping. Similarly, plasma circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) may be used as a source of tumor-derived genetic material. ctDNA is shed into the vasculature from tumor deposits, and while ctDNA is more plentiful than DNA derived from CTCs, nucleic acid analyses are complicated by the high background of cell-free DNA shed from normal cells. Both technologies are evolving rapidly and will play important roles in monitoring patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC (18–24).

To compare EGFR genotyping approaches, we undertook a prospective multi-institutional study as part of the CTC Stand-Up-To-Cancer (SU2C) Dream Team collaboration between Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). At all four institutions, patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC scheduled to have a repeat tumor biopsy at the time of acquired resistance to an EGFR TKI had coincident blood sampling for CTC and ctDNA analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We performed a pilot study in a prospective, multi-institution fashion between 2012 and 2013. The primary objectives were to demonstrate the feasibility of testing for EGFR mutations from captured CTCs and to assess the concordance of genotyping between CTCs and tumor tissue. An evaluation of the concordance of ctDNA from plasma was a secondary objective.

Patients were eligible if they had advanced EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC, clinical resistance to an EGFR TKI (gefitinib, erlotinib, or afatinib) and were undergoing a repeat biopsy for tumor genotyping as part of their routine clinical care. Patients with Stage III disease were included if they had recurrent disease following locoregional treatment and had developed resistance to a primary EGFR TKI. EGFR genotyping was performed on the tissue biopsies according to each institution’s standard in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (see Supplementary Table S1).

Blood collection was performed within 30 days of the repeat biopsy (either before or after) and consisted of three 10-mL tubes of peripheral blood in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-containing vacutainers. The blood samples were transported to the local CTC lab at each institution within 6 hours of being drawn for processing. The protocol was approved by the local IRB at each site, and all patients signed informed consent. Funding for the study was provided by SU2C. This study has been registered on www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01734915).

CTC Isolation and Molecular Analyses

As part of the CTC SU2C Dream Team collaboration, the Herringbone CTC technology (HbCTC-Chip) developed at MGH was established at each collaborating institution using extensive training and quality control procedures. Whole blood collected from patients was divided into discrete aliquots for CTC isolation, plasma isolation, and exploratory material. CTCs were isolated using the HbCTC-Chip at each institution. 10 mL of blood was drawn in EDTA tubes and processed on the HbCTC-Chip as previously described (25). The HbCTC-Chip is a chamber whose walls are coated with EpCAM antibodies and whose design induces turbulent flow, maximizing CTC capture. Lysis of captured cells was achieved in situ, by in-line flowing of nucleic acid extraction reagents (RLT plus buffer; Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). The resulting lysates were then frozen and shipped to MGH where they were stored at −80°C until extraction. DNA and RNA were extracted using the Qiagen Allprep DNA/RNA Micro kit (Venlo, Netherlands) and eluted into 50 uL EB buffer. Samples were concentrated to 8 uL using the Thermo Scientific Savant ISS110 SpeedVac system.

The T790M mutant allele was then enriched using the EKF Molecular Diagnostics PointMan EGFR T790M DNA Enrichment Kit (Cardiff, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. This assay is a highly sensitive PCR-based platform that suppresses amplification of wild-type sequences followed by direct nucleotide sequencing of the mutant-enriched product. As there are no reagents encoding the mutant sequence introduced into the reaction, the false positive rate is especially low (see Supplementary Figure S1). The enriched PCR product was sequenced using the Applied Biosystems BigDye v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit followed by fragment separation and sequence detection on the ABI3730XL DNA Analyzer at an MGH DNA core facility. Manual inspection of the individual trace files was done by investigators blinded to the results of the tissue biopsy genotyping to ascertain T790M mutation status.

For ctDNA analyses, blood was centrifuged to separate plasma from peripheral blood cells within 6 hours of collection. Plasma was stored at −80°C until shipment to Roche Molecular Diagnostics, where the DNA from at least 500 uL of plasma was extracted using a modification of the cobas® DNA Sample Preparation Kit (26). Plasma DNA extracts were analyzed for the presence of the T790M mutation using the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) as previously described (26).

Statistical Considerations

Categorical variables were tabulated by frequency and percentage. Measurement of diagnostic concordance among genotyping methods was done using Cohen’s kappa, and McNemar’s test used to judge significance. Percent agreement values were calculated based on the main diagonal in 2×2 tables and are provided with 95% Exact Binomial CI. Post-hoc power analysis to test the alternative hypothesis that %agreement will be at least 20% greater than 50% assumed under the null suggest that the study has between 72% to 80% power (for 21 to 30 matched pairs) with target significance level of 0.1. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (Graphpad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Patients and biopsy-derived genotypes

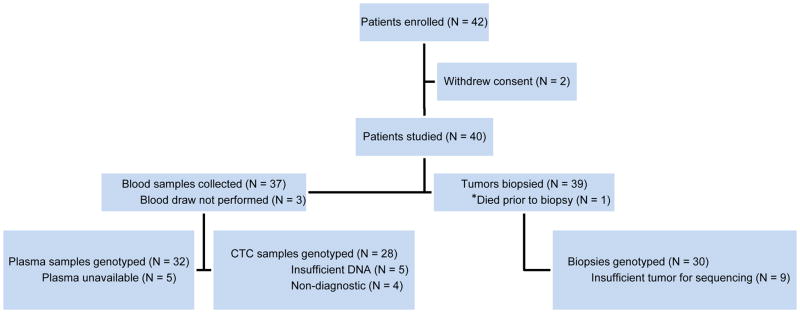

Forty-two patients were enrolled (Figure 1). Two withdrew consent before the study blood samples were drawn; no data were collected for these patients and they are not included in the analyses. Clinical characteristics of the 40 patients studied are summarized in Table 1. Among these, 29 (73%) patients had an exon 19 deletion EGFR mutation, 8 (20%) had the recurrent L858R mutation and 3 (8%) had other rare variants. All but four were on an EGFR TKI at study enrollment.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. Prospective, multi-institution clinical trial: Patients registered, diagnostic study assignments, and exclusions.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | |

| Range | 44–90 | |

|

| ||

| Female sex | 26 | 65 |

|

| ||

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| IIIA | 2 | 5 |

| IIIB | 4 | 10 |

| IV | 34 | 85 |

|

| ||

| EGFR-sensitizing mutation | ||

| Exon 19 deletion | 29 | 73 |

| L858R | 8 | 20 |

| Other* | 3 | 8 |

|

| ||

| Most recent treatment regimen | ||

| Single-agent erlotinib | 18 | 45 |

| Single-agent afatanib | 3 | 8 |

| Erlotinib plus chemotherapy | 11 | 28 |

| Erlotinib plus bevacizumab | 3 | 8 |

| Afatanib plus cetuximab | 1 | 3 |

| Chemotherapy | 4 | 10 |

Including G719C, E709K, and E709A+G719C

The majority of tumor samples were obtained from biopsies of lung tumors (38%), pleural masses (8%), or pleural fluid aspirates (10%). Overall, 30 (77%) patients had a biopsy with sufficient tumor tissue for genotyping, although pleural fluid aspirates were non-diagnostic in all four cases (Table 2). Among the patients with sufficient material for genotyping, the T790M mutation was detected in 14/30 (47%) patients (see Supplementary Table S2), including 10/19 patients with the exon 19 deletion, 4/8 with the L858R, and 0/3 with another primary EGFR mutation. The original EGFR activating mutation was detected in all cases with sufficient material for genotyping.

Table 2.

Clinical biopsy details

| Characteristic | Total biopsies (N = 39) | Sufficient material (N = 30) | Insufficient material (N = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | |||

| Lung | 15 | 13 | 2 |

| Pleura/Pleural fluid | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Liver | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Other | 11 | 10 | 1 |

|

| |||

| Type of biopsy | |||

| Percutaneous needle | 32 | 27 | 5 |

| Bronchoscopy/EBUS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Pleural fluid collection | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Open surgical | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: EBUS, endobronchial ultrasound

Because only 30 out of 40 patients had sufficient material for genotyping from the tumor biopsy done concurrently with the study blood collection, we reviewed the medical records of the participants to learn if there were additional tumor biopsies performed in the setting of acquired resistance but outside the 30-day window of proximity to the blood draw. Thirty-six patients had additional tumor biopsies; 16 were done in the setting of acquired resistance to an EGFR TKI. The added resistance biopsies either preceded the study (8 cases; 2–49 months) or were done subsequently (8 cases; 5–15 months). Among 10 cases for which genotyping was not successfully performed using the primary study biopsy specimen, additional resistance biopsies were available in 7 cases (T790M-positive in 6 cases and negative in 1 case) while the other three patients had additional tissue biopsies done prior to the development of clinical resistance. Altogether, 25/40 (63%) patients had the T790M mutation detected in at least one biopsy sample.

CTC and ctDNA-derived genotypes

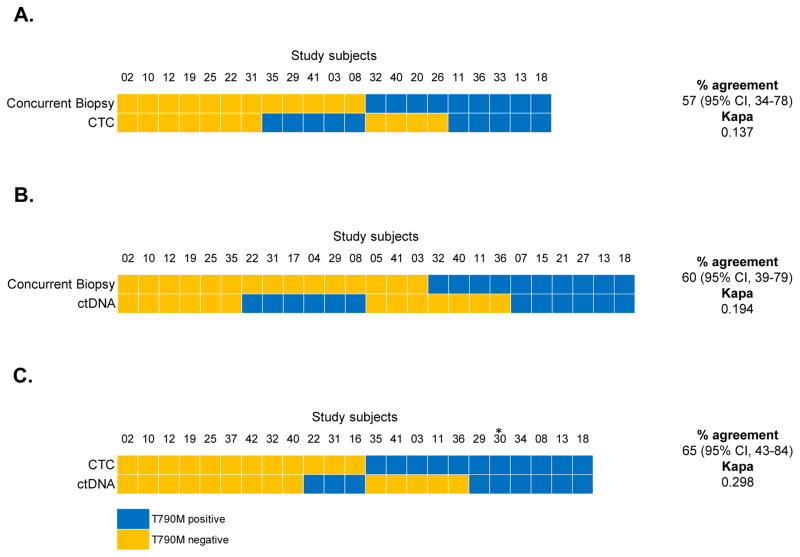

Blood was collected from 37 patients for CTC isolation. Twenty-eight CTC isolates (76%) had enough genetic material for genotyping, and the T790M mutation was demonstrated in 14/28 (50%) cases with the remaining 14 cases sequenced as wild-type at this nucleotide position. Among 21 patients with sufficient material for concurrent CTC and tumor biopsy-derived genotyping, 12 (57%) were concordant for T790M mutation status (κ = 0.137; Figure 2A). For 5 patients in whom CTCs were T790M-positive but the concurrent study biopsy was negative, additional biopsies were T790M-positive in 3 cases. Thus, when all biopsies were considered (rather than just the concurrent primary study biopsy), the percent agreement between CTC and tissue biopsy was 74% (κ = 0.485; Table 3). Notably, tumor biopsy and CTC analyses were complementary in providing information for patients with non-diagnostic procedures. For instance, of the 10 patients with insufficient biopsy material, 7 had successful CTC-derived genotypes, of which 5 were concordant with an alternate tumor biopsy.

Figure 2.

Concurrent tissue biopsy, CTC, and ctDNA analyses. (A) Comparison of T790M mutation status by CTC analysis and tissue biopsy. Only patients with sufficient material for genotyping by both methods are included. (B) Comparison of T790M mutation status by ctDNA analysis and tissue biopsy. (C) Comparison of T790M mutation status by CTC and ctDNA analysis.

*Patient died prior to concurrent biopsy. Although CTC and ctDNA samples were drawn and analyzed, this patient is not included in tissue biopsy concordance calculations.

Table 3.

Statistical Comparison of T790M genotyping

| Comparison | % agreement | 95% CI | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTC vs All biopsy | 74 | 54–89 | 0.485 |

| ctDNA vs All biopsy | 61 | 42–78 | 0.228 |

| CTC/ctDNA vs All biopsy | 69 | 52–84 | 0.35 |

Abbreviations: CTC, circulating tumor cell; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA

Circulating tumor DNA was available from 32 of the 37 collected blood samples, with T790M detected in 16 (50%) and the remaining 16 samples wildtype at this nucleotide position. Among the 25 patients with sufficient material for concurrent ctDNA and tumor biopsy-derived genotyping, 15 (60%) were concordant for T790M mutation status (κ = 0.194; Figure 2B). For 6 patients in whom plasma analysis was T790M-positive but the concurrent study biopsy was negative, additional biopsies were T790M-positive in one case. Thus, when all biopsies were considered (rather than just the concurrent primary study biopsy), the percent agreement between ctDNA and tissue biopsy was 61% (κ = 0.228; Table 3). The null hypothesis of agreement between the methods was not rejected for any test. Contingency tables for these statistics are also presented separately in Supplementary Figure S2.

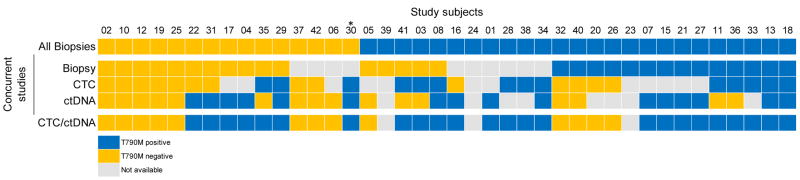

Material for matched CTC- and ctDNA-derived genotyping was available in 23 cases, of which 15 (65%) were concordant for T790M mutation status (κ = 0.298; Figure 2C). Among the 8 discordant cases, the CTC genotype matched the concurrent tumor biopsy in 4 cases (6 for all tumor biopsies) and the ctDNA genotype matched the biopsy in 3 cases (2 for all tumor biopsies). When both blood-based analyses were combined, T790M genotyping was successful in 37/37 (100%) cases for which a blood sample was drawn for analysis (37/40 (93%) of all cases). The combination of CTC and ctDNA genotyping also identified the presence of T790M in 14 (35%) patients in whom the concurrent biopsy was indeterminate or T790M negative. Overall T790M positive, negative, and non-diagnostic results are summarized per genotyping modality in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive tissue biopsy, CTC, and ctDNA analyses. (A) T790M mutation status by biopsy, CTC, and ctDNA genotyping. The top panel reflects cumulative evaluation of T790M status across all biopsies in which EGFR genotyping was done and available for review, including those prior to the onset of EGFR TKI resistance. If the patient had discordant tissue biopsies, T790M was considered positive if present in any single biopsy. T790M is listed as positive if detected in any tissue biopsy. The bottommost panel reflects a cumulative evaluation of T790M status across the two blood-based analyses. If the patient had discordant results, T790M was considered positive if detected in either CTCs or ctDNA. Likewise, if genotyping was unsuccessful in either CTC or ctDNA, the listed genotype reflects the result of the successful modality. Samples not available (gray boxes) reflect either lack of tumor in biopsy, insufficient tumor for molecular characterization or inability to obtain biopsy (concurrent biopsy); blood sample not drawn, insufficient material after CTC isolation for genotyping or performance of an unsuccessful assay (CTC); or plasma sample not drawn (ctDNA).

*Patient died prior to concurrent biopsy. Although CTC and ctDNA samples were drawn and analyzed, this patient is not included in tissue biopsy concordance calculations.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective multi-center pilot study, we examined patients with EGFR-mutant tumors who had acquired resistance to an EGFR TKI and compared the results of blood-based T790M genotyping, using either CTCs or ctDNA, with standard clinical platforms for tumor biopsy-based genotyping. Our study produced two main findings: 1) both CTC- and ctDNA-based genotyping results are generally comparable, although not identical, to those derived from tissue-based genotyping, and 2) at a single point in time, each of the three modalities were non-diagnostic for the T790M genotype in about one-quarter of patients. Together, these observations provide an initial framework with which to consider the application of non-invasive blood-based genotyping in the clinical management of patients with lung cancer developing resistance to first-line TKIs.

For all three analytic platforms, the overall T790M mutation-positive rate was approximately 50%, consistent with previous biopsy series (5,6). However, concordance with either of the two blood-based genotyping platforms was highest for the comparison between a single CTC measurement and the combined results of multiple tumor biopsies. The observed discrepancies among biopsy, CTC and ctDNA results likely relate to both intrinsic biological considerations as well as technological differences.

Although radiographically-directed needle biopsies of recurrent or metastatic tumors are currently the clinical standard for EGFR genotyping in the setting of acquired resistance, they have drawbacks including the possibility of insufficient tissue and/or complications of the invasive procedure. In our study, 23% of patients in whom a biopsy was attempted had inadequate tumor content for genotyping within their needle biopsy or aspirate. This failure rate is higher than prior single center reports of genotyping lung cancer patients at the time of diagnosis (27,28), but it is in line with prior multicenter studies and likely reflects real world results (29). Although it has been successful in other settings (30,31), in our cohort, thoracentesis was a particularly unsuccessful method, with none of the four samples yielding sufficient material for genotyping.

While no serious complications were reported from tumor biopsies performed in this study, non-invasive blood-based assays have an inherent appeal in terms of risk and patient comfort. They also have a theoretical advantage of sampling tumor cells from multiple lesions, whereas a biopsy is restricted to a single site of disease. In our cohort, the frequency of successful blood-based genotyping (70 and 80% for CTCs and ctDNA, respectively) was comparable to that of diagnostic tumor biopsies, and importantly, failures were non-overlapping among the three platforms. When considered as combined or complementary methods, genotyping from CTC or ctDNA was successful in 100% of cases for which a blood sample was drawn (93% of all cases). Furthermore, our protocol only included blood sampling at a single point in time, within 30 days of the biopsy around which the patient’s enrollment was based. Serial blood draws for CTCs or ctDNA analyses may have further improved their independent success rates, with minimal added risk to patients. Indeed, such serial monitoring of EGFR Exon 19 deletions, L858R, and T790M mutations in plasma indicates that mutation detection is correlated with initial response to erlotinib as well as disease progression (26,32). In other malignancies such as breast cancer, ctDNA detection sensitivity is significantly increased with serial sampling (33).

One limitation of our study is that the noninvasive genotyping technologies chosen at the time of trial initiation in 2012 have continuously evolved in the interim. For example, methods of microfluidic CTC isolation have further improved, producing greater numbers of CTCs with lower leukocyte contamination (34). Nonetheless, this study represents the first prospective evaluation of a microfluidic CTC isolation platform across multiple institutions, demonstrating feasibility in dissemination and standardization of the technology. Similarly, ctDNA genotyping was performed using an adapted FDA-approved companion diagnostic for EGFR mutation testing, but next generation genotyping and sequencing strategies will continue to emerge (19,24), and the relative advantages of various technologies will require continued reappraisal.

Perhaps the most intriguing considerations emerging from our study are the potential biological differences inherent in blood-based sampling versus tumor biopsy. As demonstrated in several reports, acquired resistance to TKIs is frequently heterogeneous, with different metastatic tumor deposits demonstrating distinct underlying mechanisms (15,35,36). Discrepancies between a single tumor biopsy and blood-based sampling may result in part from the fact that the latter likely includes material from multiple disease sites. In contrast to acquired resistance-associated mutations like T790M, each initial EGFR sensitizing mutation is an early “truncal” event in the pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma, and previous studies have not detected significant heterogeneity across multiple biopsies (5,37). Indeed, for the primary EGFR driver mutations L858R and Exon 19 deletions, the concordance between ctDNA-based and tumor biopsy-based genotyping was markedly higher than it was for the secondary T790M mutation (97 and 87%, respectively, versus 60%; Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S3). Thus, the subclonal genetic landscape of secondary drug resistance-associated mutations may contribute in large part to the discordant cases in our analysis.

In addition to their differences with respect to tumor biopsies, CTCs and ctDNA themselves represent different biological processes: the former constitutes an invasive subset of cancer cells capable of intravasating into the vasculature, while the latter reflects lysis of cells from tumor deposits. Given these biological considerations, establishing a true technological “gold standard” for tumor genotyping may be challenging, and these assays may instead require standardization based on functional consequences, namely their ability to predict therapeutic responsiveness. Early studies show the majority of patients with the T790M mutation detectable on a tumor biopsy respond to 3rd-generation T790M-selective TKIs, although some patients whose tumor is scored as T790M negative also respond. This discrepancy may reflect inadequate sampling in the setting of tumor heterogeneity. In fact, eight patients in our study who had indeterminate or T790M-negative study biopsies but had T790M detected using a blood-based method went on to receive the 3rd generation EGFR inhibitors AZD9291 or CO-1686 and had clinical data available for review. Of these, five patients had disease stabilization or partial response. In this context, the combination of CTC- and ctDNA-genotyping together identified T790M in a total of 14 (35%) patients in whom the concurrent study biopsy was either negative or indeterminate, potentially identifying additional patients with disease responsive to 3rd-generation EGFR inhibitors. When all three concurrent genotyping modalities (study biopsy, CTC, and ctDNA) were combined, the T790M mutation was detected in 73% of patients.

Our study was nearly completed before the 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs entered clinical trials at our institutions, hence further study will be required to correlate clinical response with the source of tumor cell genotyping. Specifically, if blood-based detection of T790M is shown to function as a predictive biomarker for mutant-selective TKIs, future studies may initially rely on such noninvasive serial monitoring assays as the first sign of drug resistance, reserving tumor rebiopsies for cases where blood-based testing is unrevealing. In addition, the relative clinical utility of CTC and ctDNA-based analyses will require further study as these technologies mature, as well as cost-based assessments. As the number of molecular diagnostic assays proliferate, our standards for their adoption will require ongoing refinement and clinical validation.

In conclusion, we studied the result of T790M genotyping from tumor biopsies, CTCs, and ctDNA in a prospective patient cohort derived from four SU2C collaborating institutions. Each analytic platform was non-diagnostic in a comparable but non-overlapping fraction of cases, such that combining CTC- and ctDNA-derived analyses yielded successful genotypes from all available blood samples. Where T790M genotypes were measured from multiple sources, these were generally concordant, but divergent genotypes were also observed, potentially reflecting both technological differences and variable sampling of tumor cell populations. Since individual tumor biopsies themselves provide an incomplete window into the heterogeneous nature of acquired drug resistance, correlation with clinical response to 3rd-generation EGFR inhibitors may ultimately provide the true “gold standard” for T790M genotyping.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

In EGFR-mutant lung cancer, the T790M gatekeeper mutation is a dominant mechanism of acquired resistance to small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The development of third-generation EGFR inhibitors capable of overcoming T790M-associated resistance has led to a need for non-invasive methods of T790M detection to guide the selection of therapy. Here we describe an exploratory study comparing genotyping, using either circulating tumor cells or circulating tumor DNA versus concurrent tumor biopsies, for the T790M mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer progressing on first line EGFR inhibitors. While generally comparable, genotyping was not identical using the three methods likely reflecting both technical and biological differences in the heterogeneous landscape of drug resistant tumor populations. We conclude that no single diagnostic test for acquired resistance, including tumor biopsy, can be considered a “gold standard” and the clinical utility of blood-based testing will need to be prospectively validated against clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This research was supported by A Stand Up To Cancer Dream Team Translational Cancer Research Award (SU2-AACR-DT0309, to D. A. Haber, M. Toner, and S. Maheswaran); Stand Up To Cancer is a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation administered by the American Association for Cancer Research.

We are grateful to the patients who have participated in this study. We thank Caitlin Koris, Courtney Hart, Allison O’Connell, Jayanthi Gudikote, Erin Ellis, Terah Hardcastle, Chris Webb, Julie Tsai and Mari Christensen for assistance with the clinical trial and technical work. We thank Ann Begovich for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

LVS is a consultant/advisory board member for Clovis, Novartis, Merrimack, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Taiho, and Boehringer Ingelheim. JVH is a consultant/advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Lilly, Genentech, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Lilly, Genentech, and Boehringer Ingelheim. GJR is a consultant/advisory board member for Ariad, Mersana, and Novartis; and has received honoraria from Celgene. PAJ is a consultant/advisory board member for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Pfizer, Merrimack, Clovis, Sanofi, and Chugai. WHK is an employee of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. AW is an employee of EKF Molecular Diagnostics, Ltd. HTT is a consultant/advisory board member for Teva. HY is a consultant/advisory board member for Clovis. WW is an employee of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. BEJ is a consultant/advisory board member for Novartis, GE Healthcare, Teva, Synta, Ariad, AstraZeneca, KEW Group, Biothera, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Puma, Merck, Transgene, Clovis, and Otsuka. TAB receives research funding from Janssen. JRW receives research funding from Janssen. JAE is a consultant/advisory board member for F-star, G1 therapeutics, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Loxo, Merck, Novartis, Red Sky, Roche, Ventana, Sanofi, Third Rock, Jounce, Agios, Aisling, Amgen, AstraZeneca, AVEO, Cell Signaling, Chugai, Cytomix, and Endo. SLS receives research funding from Janssen. RK is an employee of Anudeza, Inc. SM receives research funding from Janssen. MT receives research funding from Janssen. DAH is a consultant/advisory board member for Cell Signaling and receives research funding from Janssen.

DAH, PAJ and BEJ receive a share of post-market licensing revenue from Lab Corp distributed by MGH and DFCI for the use of EGFR genotyping. WW is an inventor on a pending patent related to plasma-based mutation testing. TAB, SLS, RK, SM, MT and DH are inventors of CTC isolation technologies (patents pending). All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lee CK, Brown C, Gralla RJ, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Tsai CM, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: a meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105:595–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:239–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3327–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:2240–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, Riely GJ, Somwar R, Zakowski MF, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS medicine. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byers LA, Diao L, Wang J, Saintigny P, Girard L, Peyton M, et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies Axl as a therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:279–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Lee JC, Lin L, Olivas V, Au V, LaFramboise T, et al. Activation of the AXL kinase causes resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Nature genetics. 2012;44:852–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sequist LV, Soria JC, Goldman JW, Wakelee HA, Gadgeel SM, Varga A, et al. Rociletinib in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:1700–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, Planchard D, Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:1689–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Network NCC. [September 24, 2014];Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Version 4.2014) 2014 Sep 24; < http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf>.

- 15.Piotrowska Z, Niederst M, Mino-Kenudson M, Morales V, Fulton L, Lockerman E, et al. Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology. Vol. 90. Chicago, Ilinois: International Journal of Radiation Oncology; 2014. Variation In Mechanisms Of Acquired Resistance Among Egfr-mutant Nsclc Patients With More Than 1 Post-resistant Biopsy; pp. S6–S7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, Ulkus L, Brannigan B, Collura CV, et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:366–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stott SL, Hsu CH, Tsukrov DI, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:18392–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Gale D, Forshew T, Piskorz AM, et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature. 2013;497:108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxnard GR, Paweletz CP, Kuang Y, Mach SL, O’Connell A, Messineo MM, et al. Noninvasive detection of response and resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer using quantitative next-generation genotyping of cell-free plasma DNA. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:1698–705. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M, Ciuleanu T, Cole R, McWalter G, et al. Gefitinib treatment in EGFR mutated caucasian NSCLC: circulating-free tumor DNA as a surrogate for determination of EGFR status. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2014;9:1345–53. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchetti A, Del Grammastro M, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, Filice G, Centi I, et al. Assessment of EGFR mutations in circulating tumor cell preparations from NSCLC patients by next generation sequencing: toward a real-time liquid biopsy for treatment. PloS one. 2014;9:e103883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni X, Zhuo M, Su Z, Duan J, Gao Y, Wang Z, et al. Reproducible copy number variation patterns among single circulating tumor cells of lung cancer patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:21083–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320659110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pailler E, Adam J, Barthelemy A, Oulhen M, Auger N, Valent A, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells harboring a unique ALK rearrangement in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:2273–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, Wynne JF, Eclov NC, Modlin LA, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. 2014;20:548–54. doi: 10.1038/nm.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas ME, Ting DT, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013;339:580–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1228522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorensen BS, Wu L, Wei W, Tsai J, Weber B, Nexo E, et al. Monitoring of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-sensitizing and resistance mutations in the plasma DNA of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer during treatment with erlotinib. Cancer. 2014;120:3896–901. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sequist LV, Heist RS, Shaw AT, Fidias P, Rosovsky R, Temel JS, et al. Implementing multiplexed genotyping of non-small-cell lung cancers into routine clinical practice. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2011;22:2616–24. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR, Jr, Tsao A, et al. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer discovery. 2011;1:44–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. Jama. 2014;311:1998–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buttitta F, Felicioni L, Del Grammastro M, Filice G, Di Lorito A, Malatesta S, et al. Effective assessment of egfr mutation status in bronchoalveolar lavage and pleural fluids by next-generation sequencing. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:691–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Lu Y, Zhu G, Lei Y, Zheng L, Qin H, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of pleural effusion and plasma samples versus tumour tissue for detection of EGFR mutation in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: comparison of methodologies. Journal of clinical pathology. 2013;66:1065–9. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mok T, Wu YL, Lee JS, Yu CJ, Sriuranpong V, Sandoval-Tan J, et al. Detection and Dynamic Changes of EGFR Mutations from Circulating Tumor DNA as a Predictor of Survival Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Treated with First-line Intercalated Erlotinib and Chemotherapy. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:3196–203. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsson E, Winter C, George A, Chen Y, Howlin J, Tang MH, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1034–47. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozkumur E, Shah AM, Ciciliano JC, Emmink BL, Miyamoto DT, Brachtel E, et al. Inertial focusing for tumor antigen-dependent and -independent sorting of rare circulating tumor cells. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:179ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graziano P, de Marinis F, Gori B, Gasbarra R, Migliorino R, De Santis S, et al. EGFR-Driven Behavior and Intrapatient T790M Mutation Heterogeneity of Non-Small-Cell Carcinoma With Squamous Histology. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:1–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hata A, Masago K, Katakami N, Imai Y, Yatabe Y. Spatiotemporal T790M heterogeneity in a patient with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2014;9:e64–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arcila ME, Oxnard GR, Nafa K, Riely GJ, Solomon SB, Zakowski MF, et al. Rebiopsy of lung cancer patients with acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors and enhanced detection of the T790M mutation using a locked nucleic acid-based assay. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:1169–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.