Abstract

Social media is rapidly being incorporated into medical education. We created a small group, reflective practice sessions by integrating specific medical cases to improve awareness about professionalism on social media. Medical scenarios were generated for reflective practice sessions on social media professionalism. Anonymous pre/post-session surveys evaluated residents' use of social media and gathered their opinions on the session. Thirty-eight of 48 (79 %) residents replied to the presession survey with 50 % (19/38) reporting daily digital media use, 76 % (29/38) witnessed unprofessional postings on social media, and 21 % (8/38) posted unprofessional content themselves. Of the 79 % (30/38) residents who attended the session, 74 % (28/38) completed the post-session survey. Residents reported the session added to the longevity of their professional career 4.11, 95 % CI (3.89–4.36). As a result of the session, they were more conscious of using the social media more professionally 3.47, 95 % CI (2.88–3.96) and would be proactive in protecting patient privacy and confidentiality on social media sites 3.96, 95 % CI (3.50–4.37). In summary, reflective practice-based sessions regarding the impact of social media on professionalism in surgery was well favored by the residents. The majority agreed that it had important implications for the longevity of their professional career. Participants reported having an increased awareness to protect patient privacy and utilize social media more professionally.

Keywords: Social media, Reflective-based approach, Education, Surgery

Introduction

The age of Internet has transformed the way society communicates and behaves. It facilitates access to personal data through social media networking and sharing. Surgery personnel, like other professionals, use social media to share and communicate with family, friends, and their respected colleagues. This new technology provides easy access to rapid communication, faster networking, and instantaneous consultations and lectures [1]. As part of the Web 2.0, social media includes blogs, wikis, podcasts, and other networking options such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. However, concern may rise when professional and personal identities may be revealed, since shared information is visible to patients, potential employers, and the general population [2].

Organization and universities have begun to take notice of this situation and have begun developing guidelines [3] that will foster awareness in handling social media in both students and residency programs. Chretien et al., reported that 60 % of the schools had incidents in which the students engaged in posting unprofessional content [4].

While there is no clear, concise, and currently relevant description of professionalism, many residency programs have introduced the role-modeling methods and feedback from patients, attending physicians, nurses, and their peers [5–7]. Other programs have incorporated reflective practice to increase awareness [8, 9]. Reflective practice is a thoughtful and a critical analysis of one's actions by assuming the perspective of an external observer—to ultimately improve their professional practice. Previous literature has discussed its valuable practicality [10, 11]. In our investigation, we evaluate the impact of reflective practice on surgery residency. We conducted a before and after survey to measure resident awareness of social media and to report their thoughts about the reflective approach methodology.

Material and Methods

The institutional review board exempted this study. Our two community-based hospitals have 16 surgery residents in each year for a combined total of 48 residents. Reflective case-based sessions were conducted once every 2 months between November 2012 and July 2013, with participating residents from all 3 years who were facilitated by one senior physician. Our fourth and final year residents were excluded as they perform their final year abroad.

Sessions lasted for 80 min and were conducted in morning conferences via an open microphone. On average, the morning conferences were attended by 38 of 48 residents. The senior physician presented cases, and after that, open discussions took place in which residents shared personal information on using social media services.

A week before each session, residents were given cases stressing the importance of nonprofessional online conduct from recent media posts along with hypothetical medical cases. The residents were also given surveys and asked to record their thoughts before and after the session about their use and understanding of the social media. Responses were gathered through the survey software eSurveysPro (www.eSurveysPro.com). The survey used an agree/disagree 1–5 rating scale ((1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neutral, (4) agree, and (5) strongly agree), multiple choice, and free text fields (Tables 1 and 2). All sessions were anonymized.

Table 1.

Preassessment survey

| Question | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| A. <30 | 45 % (17/38) |

| B. 30–39 | 55 % (21/38) |

| C. 40–49 | None |

| D. 50–59 | None |

| Gender | |

| Male | 84 % (32/38) |

| Female | 16 % (6/38) |

| I am comfortable using social media | |

| A. Strongly disagree | None |

| B. Disagree | 10 % (4/38) |

| C. Neutral | 16 % (6/38) |

| D. Agree | 42 % (16/38) |

| E. Strongly agree | 32 % (12/38) |

| Last year I used | |

| A. Facebook | 92 % (35/38) |

| B. Twitter | 29 % (11/38) |

| C. LinkedIn | 37 % (14/38) |

| D. Google+ | 18 % (7/38) |

| E. Other | 8 % (3/38) |

| I use social media | |

| A. Daily | 50 % (19/38) |

| B. Once a week | 32 % (12/38) |

| C. Once a month | 13 % (5/38) |

| D. < 1 a month | 5 % (2/38) |

| I use social media for | |

| A. Personal reasons | 87 % (33/38) |

| B. Professional reasons | None |

| C. Both | 13 % (5/38) |

| Over the last year, I used social media to discuss work matter with a fellow colleague | |

| A. Daily | None |

| B. Once a week | None |

| C. Once a month | 5 % (2/38) |

| D. 1–2 times | 16 % (6/38) |

| E. Never | 79 % (30/38) |

| Unprofessional posting observed over last 6 months | |

| A. 0 | 24 % (9/38) |

| B. 1 | 71 % (27/38) |

| C. 2 | 5 % (2/38) |

| D. >3 | None |

| Personally posted unprofessional contents | |

| A. Yes | 21 % (8/38) |

| B. No | 79 % (30/38) |

| People connected with | |

| A. Attending physician | 50 % (19/38) |

| B. Peers | 84 % (32/38) |

| C. Nurse | 42 % (16/38) |

| D. Medical assistant | 16 % (6/38) |

| E. Others | 32 % (12/38) |

| Competency in navigating privacy settings | |

| A. Very competent | 58 % (22/38) |

| B. Somewhat competent | 32 % (12/38) |

| C. Somewhat incompetent | 5 % (2/38) |

| D. Incompetent | 5 % (2/38) |

| Impact of social media on your profession | |

| A. It has had a positive impact | 3 % (1/38) |

| B. No impact | 92 % (35/38) |

| C. It has had a negative impact | 5 % (2/38) |

Table 2.

Post-assessment survey

| Question | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Was completing the pre-session survey helpful? | |

| A. No | 21 % (6/28) |

| B. Somewhat | 61 % (17/28) |

| C. Very | 18 % (5/28) |

| Was previewing the specific case scenarios prior to the session useful? | |

| A. No | 11 % (3/28) |

| B. Somewhat | 39 % (11/28) |

| C. Very | 50 % (14/28) |

| The open discussion format for the session was useful? | |

| A. No | None |

| B. Somewhat | 18 % (5/28) |

| C. Very | 82 % (23/28) |

| Would a didactic format been more useful? | |

| A. No | 100 % (28/28) |

| B. Yes | None |

| Did the microphone or the knowledge of you being recorded, inhibit your participation in any way? | |

| A. No | 82 % (23/28) |

| B. Yes | 4 % (1/28) |

| C. Possibly | 14 % (4/28) |

| Allotted time was sufficient to review survey results during the session? | |

| A. No | 50 % (14/28) |

| B. Yes | 50 % (14/28) |

| Enough time was given for the session? | |

| A. No | 39 % (11/28) |

| B. Yes | 61 % (17/28) |

| Were you comfortable discussing your opinion in the attending’s presence? | |

| A. No | 3.5 % (1/28) |

| B. Yes | 93 % (26/28) |

| C. Somewhat | 3.5 % (1/28) |

| Should a peer or an outside professional facilitate the session? | |

| A. No | 57 % (16/28) |

| B. Yes | 43 % (12/28) |

| 1–5 rating scale (1. strongly disagree; 2. disagree; 3. neutral; 4. agree; and 5. strongly agree) | Mean (95 % CI) |

| The session was focused on professionalism? | 3.91 (3.45–4.47) |

| This session made me reflect on my own use of social media. | 3.75 (3.27–4.11) |

| This session made me think about surgery in a way I have not yet done. | 3.61 (2.95–3.97) |

| This session added to my understanding of professionalism. | 3.91 (3.56–4.25) |

| This session made me think differently about how I will use social media in the future. | 3.21 (2.51–4.29) |

| I will apply material learned in this session to my residency training. | 3.52 (3.05–4.06) |

| Rate the importance of this topic in the following | |

| A. Surgery in general | 3.93 (3.56–4.28) |

| B. Surgery residency | 3.95 (3.58–4.39) |

| C. Your future career | 4.11 (3.89–4.36) |

| Because of this session | |

| A. I will modify social media usage personally. | 3.48 (2.87–3.98) |

| B. I will modify social media usage professionally. | 3.47 (2.88–3.96) |

| C. I will be more proactive in protecting patient privacy and confidentiality throughout social media. | 3.96 (3.50–4.37) |

| After participating in this session, my use of social media will | |

| A. Increase | None |

| B. Remain unchanged | 96 % (27/28) |

| C. Decrease | 4 % (1/28) |

| What were the positives of our session | Free text |

| What were the negatives of our session | Free text |

| This session can be improved by | Free text |

| Any further thoughts or comments | Free text |

Results

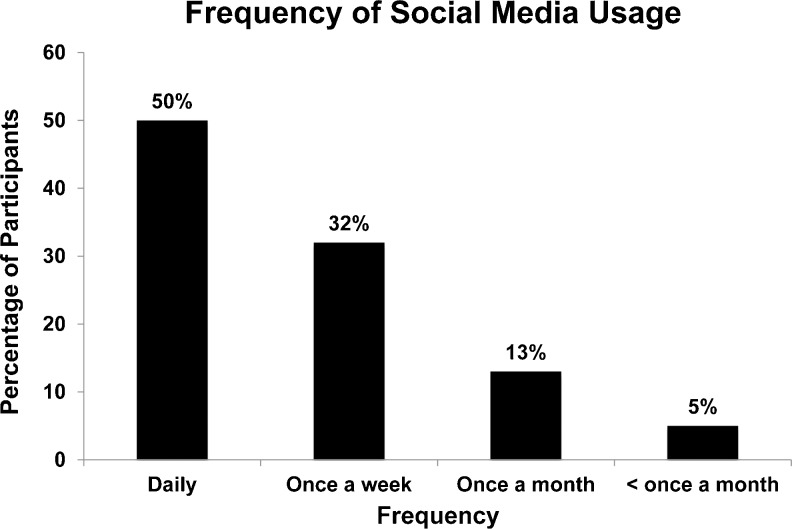

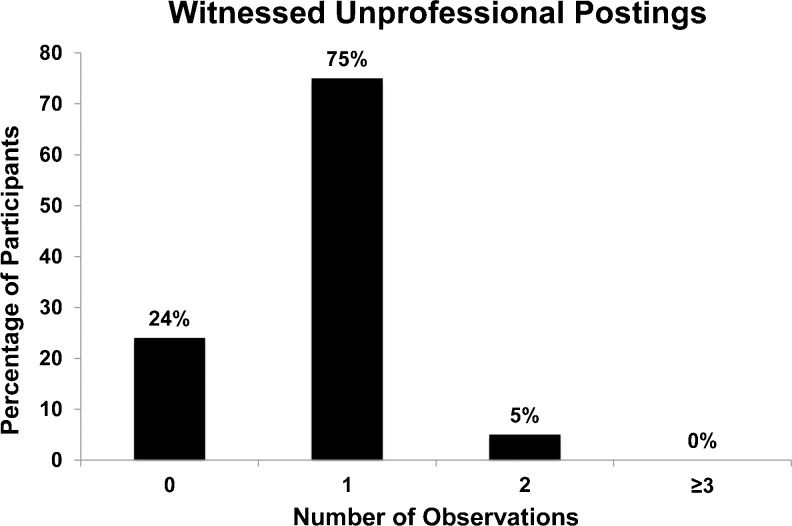

A total of 79 % (38/48) of the residents completed the presession survey (Table 1). The average respondents were 84 % (32/38) male residents and 16 % (6/38) female residents. The average age was 34. Fifty percent (19/38) reported daily usage of social media (Fig. 1). Residents often “friended” colleagues, most commonly peers (84 %; 32/38) and physicians (50 %; 19/38). Seventy-one percent (27/38) reported seeing unprofessional posts (Fig. 2), and 21 % (8/38) posted unprofessional content themselves. Majority felt social media had little to no impact on their professional careers.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of social media usage demonstrated in percentage of participants

Fig. 2.

Witnessed unprofessional postings on social media over the last 6 months

After completing the survey, 79 % (30/38) attended the sessions. After the session, 93 % (28/30) completed the survey (Table 2). Residents expressed satisfaction with the layout of the session (3.91, 95 % CI (3.45–4.47)) and were comfortable expressing their opinion in front of the attending physician 93 % (26/28). Residents also reflected on their own use of social media as a result of the session (3.75, 95 % CI (3.27–4.11)), which they felt added to their understanding of professionalism (3.91, 95 % CI (3.56–4.25)). Eighty-six percent (24/28) felt that the session added longevity to their career. All stated that they would be more aware of protecting patient information and playing an active professional role while using social media services (3.96, 95 % CI (3.50–4.37)). Seventy-five (21/28) percent agreed that the session would change how they used social media. However, 96 % (27/28) did not feel they would change the time spent on social media.

Discussion

Maintaining professionalism on social media is becoming an important part of medical practice. Risks highlighted in previous literature are based on unprofessional patient–physician contact [12] along with f “tweets” and “posts.” Our presession surveys show that many residents witness unprofessional online content as reported in previous literature as well [4, 13, 14]. After the reflective approach session, residents stated they had improved their awareness in protecting patient privacy on digital media and would take a more proactive approach in ensuring professional use of social media and that they may modify their activity when using digital media both professionally and personally.

We surveyed our residents prior to our sessions to ensure that they were familiar with the popular social media sites and whether they had witnessed unprofessional use of social media. Fifty-two percent of our residents reported daily usage of social media. These numbers were somewhat similar to another study in which 44.5 % of the trainees used social media daily [15]. The incidence of unprofessional conduct online is common (60 %) among US medical universities [4]. Seventy-one percent of our residents reported seeing unprofessional postings, and 21 % posted something unprofessional themselves. Universities and other institutions (American Medical Association) are now taking action to promote professionalism [16]. For example, the University of Florida recognizes social media as a current form of communication and has implemented policies in an effort to raise awareness of a mature, responsible, and professional attitude when interacting online [17]. Whether it is imaging related or any other medical chart information, patient privacy must be protected at all cost. The American Medical Association has released its own policy on “professionalism in the use of social media” (Appendix).

To date, no clear, concise, or reliable measuring tool has been constructed to measure professionalism. Many institutions continually rely on the outdated role modeling and feedback methods, neither of which is suitable to communicate an effective approach in guiding appropriate usage of digital media. Reflective approach has been utilized by numerous specialties [8, 9, 18], which enhance professional competence through thoughtful and critical analysis of one's actions by assuming the perspective of an external observer. Case-based scenarios like the ones in our study are a way to introduce a topic of professionalism [19].

Participants were content with the session and felt it added to the longevity of their medical careers. Participants agreed about the impact the session had on guiding how they would navigate the social media both professionally and personally. However, they did not feel it would change the time one spends utilizing social media. Our reflective practice session may be effective in familiarizing residents with social media professionalism, and it may help them establish personal and professional boundaries.

Our investigation shows that 90 % (34/38) of the participants are social media competent. Previous literature discusses that while those born after 1980 are somewhat “native” to the digital age, people born before 1980 are still somewhat considered immigrants to the digital age [20] due to the difficulty adopting to the intricacies of the social media. The authors state that these differences may soon be gone, and further distinctions may arise among the natives.

A few limitations exist. Given the small number of participants in our investigation, its applicability to larger institutions needs further assessment. We also did not take into account the interests of the participants, which can vary and give insight on who visits what site and the general topics of those sites. We did not take into account the preferable social media platform by age or sex. Lastly, familiarity with social media varied and could have influenced the general feeling of the session. While our study was conducted among the residents, the results of our investigations demonstrated a positive influence on the professional attitude of the residents. We suggest reflective case-based approach with other members directly involved with patient care.

Conclusion

In summary, reflective practice-based sessions regarding the impact of social media on professionalism in surgery was well favored by the residents. The majority agreed that it had important implications for the longevity of their professional career. Participants reported having an increased awareness to protect patient privacy and utilize social media more professionally.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix. Opinion 9.124—Professionalism in the Use of Social Media

The Internet has created the ability for medical students and physicians to communicate and share information quickly and to reach millions of people easily. Participating in social networking and other similar Internet opportunities can support physicians' personal expression, enable individual physicians to have a professional presence online, foster collegiality and camaraderie within the profession, and provide opportunity to widely disseminate public health messages and other health communication. Social networks, blogs, and other forms of communication online also create new challenges to the patient–physician relationship. Physicians should weigh a number of considerations when maintaining a presence online:

Physicians should be cognizant of standards of patient privacy and confidentiality that must be maintained in all environments, including online, and must refrain from posting identifiable patient information online.

When using the Internet for social networking, physicians should use privacy settings to safeguard personal information and content to the extent possible, but should realize that privacy settings are not absolute and that once on the Internet, content is likely there permanently. Thus, physicians should routinely monitor their own Internet presence to ensure that the personal and professional information on their own sites and, to the extent possible, content posted about them by others is accurate and appropriate.

If they interact with patients on the Internet, physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries of the patient–physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.

To maintain appropriate professional boundaries, physicians should consider separating personal and professional content online.

When physicians see content posted by colleagues that appears unprofessional, they have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions. If the behavior significantly violates professional norms and the individual does not take appropriate action to resolve the situation, the physician should report the matter to appropriate authorities.

Physicians must recognize that actions online and content posted may negatively affect their reputations among patients and colleagues, may have consequences for their medical careers (particularly for physicians-in-training and medical students), and can undermine public trust in the medical profession.

References

- 1.Cartledge P, Miller M, Phillips B. The use of social-networking sites in medical education. Med Teach. 2013;35(10):847–857. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.804909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson LA, Black E, Duff WP, Paradise Black N, Saliba H, Dawson K. Protected health information on social networking sites: ethical and legal considerations. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chretien KC, Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;127(13):1413–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chretien KC, Greysen SR, Chretien JP, Kind T. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1309–1315. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkman WB, Geraghty SR, Lanphear BP, Khoury JC, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Dewitt TG, Britto MT. Effect of multisource feedback on resident communication skills and professionalism: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(1):44–49. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruess R, McIlroy JH, Cruess S, Ginsburg S, Steinert Y. The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: a preliminary investigation. Acad Med. 2006;81(10 Suppl):S74–S78. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200610001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn G, Garner J, Sawdon M. 'You're judged all the time!' Students' views on professionalism: a multicentre study. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):814–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ker JS. Developing professional clinical skills for practice—the results of a feasibility study using a reflective approach to intimate examination. Med Educ. 2003;37(Suppl 1):34–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.37.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. The impact of prompted narrative writing during internship on reflective practice: a qualitative study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13(5):723–733. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 Pt 1):1185–1188. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians' professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1203–1210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain SH. Practicing medicine in the age of Facebook. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):649–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0901277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chretien KC, Goldman EF, Beckman L, Kind T. It's your own risk: medical students' perspectives on online professionalism. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 Suppl):S68–S71. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, Knettler TR, Rattner SL, Stern DT, Veloski JJ, Hodgson CS. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2673–2682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson LA, Dawson K, Ferdig R, Black EW, Boyer J, Coutts J, Black NP. The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):954–957. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Medical Association. Opinion 9.124—Professionalism in the use of social media. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9124.page

- 17.UF Health. Use of social networking sites. Florida. http://osa.med.ufl.edu/policies/use-of-social-networking-sites/

- 18.Parrish DR, Crookes K (2013) Designing and implementing reflective practice programs—key principles and considerations. Nurse Educ Pract [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Metter D, Harolds J, Rumack CM, Relyea-Chew A, Arenson R. The disruptive professional case scenarios. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(4):494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gholami-Kordkheili F, Wild V, Strech D. The impact of social media on medical professionalism: a systematic qualitative review of challenges and opportunities. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e184. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]