Abstract

During surgery for colorectal cancer, the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) may be ligated either directly at the origin of the IMA from the aorta (high ligation) or at a point just below the origin of the left colic artery (low ligation). Sixty patients of left colonic and rectal cancer undergoing elective curative surgery in 2007 and 2008 were selected for this observational study. The resected lymph nodes were grouped into three levels: along the bowel wall (D1), along IMA below left colic (D2), and along the IMA and its root (D3). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 20.0. D2 level was involved pathologically in 20 (33.3 %) and D3 in six out of 44 (13.6 %) patients. The median nodal yield with high and low ligation were 33 and 25, respectively (p = 0.048). Median overall survival for high ligation was 62 months versus 42 months for low ligation (p = 0.190). High ligation of the IMA for rectal and left colonic cancers can improve lymph node yield, thus facilitating accurate tumor staging and thus better disease prognostication, but the survival benefit is not significant.

Keywords: High ligation, Low ligation, Inferior mesenteric artery, Survival benefit, Left colon, Rectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancers (CRC) account for nearly 10 % of all cancers worldwide. It is the third most common cancer in men and second most common in women [1]. Left colonic and rectal cancers represent just under two thirds of all colorectal malignancies [2]. Resection of the tumor with adequate margins and associated mesentery, including the lymph nodes, remains the primary modality of treatment of colorectal cancer. Patients with positive lymph nodes may also benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, lymph node analysis is one of the critical factors for therapeutic decision making [3]. During surgery for colorectal cancer, the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) may be ligated either directly at the origin of the IMA from the aorta (high or flush ligation) or at a point just below the origin of the left colic artery (low ligation). The high ligation technique allows en bloc removal of additional nodes at and around the origin of the IMA; however, its advantage remains debatable.

Moynihan recommended high ligation as early as in 1908 [4]; there is still no consensus as to which method should be adopted. The aim of the present study is to analyze the pattern of involvement of lymph nodes in left-sided colorectal cancer and to address the issues on the ligation of the vessels.

Materials and Methods

This observational study was carried out on 60 patients admitted in the surgical ward of our hospital chosen irrespective of age and sex undergoing left-sided colorectal cancer surgery from January 2007 to December 2008. However, patients undergoing emergency surgery for colorectal cancer to relieve obstruction were excluded. These patients had histologically proven adenocarcinoma of the left colon or rectum and underwent high or low ligation of the IMA depending on the surgeon’s choice. As per the institutional protocol, the surgical process was explained to all patients and informed consent was obtained prior to any surgical intervention.

The plane between the back of the inferior mesenteric vessels and the gonadal vessels, ureter, and preaortic sympathetic nerves was identified. In patients undergoing high ligation, dissection of all the lymph nodes around the root of the IMA was done before IMA ligation and excision in close proximity to the aorta, irrespective of the intraoperative finding of presence or absence of swollen lymph nodes. Ligation of the IMA at or below the level of the origin of the left colic artery was termed as low ligation, and in this case, removal of only pericolic nodes along with the primary cancer was done. The specimen was divided into three groups: first was mesorectum containing inferior mesenteric artery; second mesorectum containing the segmental branches, like left colic, sigmoidal, and superior rectal artery (SRA); while the third group included mesorectum containing paracolic vascular branches and lymph nodes with bowel specimen. Postoperatively, after fixation of specimen in formalin for 72 h, lymph nodes along the course of different vessels, namely IMA, left colic, superior rectal artery, sigmoidal branches, and along the bowel wall, were removed separately. For all practical purposes, these were grouped into three levels: level I being along the bowel wall (D1); level II was along the branches of IMA namely left colic, SRA, and sigmoidal branches (D2); while level III was along the IMA and its root (D3). Microscopy of these lymph nodes was done in pathology section, and the malignant deposits were located.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical calculations were performed with the help of SPSS software for Windows, version 20.0 (Armonk, NY, IBM Corp.). The data were entered into Microsoft excel sheet and imported to SPSS. Chi-square and independent sample T test were done to find out the significance value besides estimation of various frequencies. Overall 5-year survival was calculated for patients with positive D2 or D3 level and Kaplan–Meier curve was generated. The significance of survival difference was estimated by log-rank test.

Results

The characteristics of the 60 patients of left-sided colon and rectal cancer who underwent planned potentially curative resection with either high or low ligation are depicted in Table 1. Table 2 shows the distribution of variables according to the various potential confounding factors. The distribution was found to be evenly balanced between the two arms as evident by the non-significant p values. Mean positive node yields of 3.9 from level D1, 0.7 from D2, and 0.1 from level D3 were obtained. The mean number of nodes examined per patient was 29.47 overall (25 by low ligation versus 31.1 by high ligation, p = 0.048). Chi-square value for method of lymph node excision versus total lymph nodes excised was 48.1 (p < 0.001). The D1 level nodes were positive for metastasis in 40 (66.6 %) cases, D2 in 20 (33.3 %), and D3 in six out of 44 (13.6 %) patients. Two (3.3 %) patients who were D3 node positive did not have metastatic deposits at D2 level; skip metastases could be a plausible explanation in these cases. Thus, the frequency of residual metastatic nodes was 13.6 % that would have been missed behind if low ligation would have been done in these patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 60 patients who underwent curative surgery

| S. no. | Patient characteristics | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age (years)a | 50 (50) (19–76) |

| 2. | Age group | |

| < 20 | 2 | |

| 21–40 | 12 | |

| 41–60 | 10 | |

| >60 | 36 | |

| Total | 60 | |

| 3. | Gender | |

| M/F | 2.75:1 | |

| 4. | Site | |

| Descending colon | 2 (3.3) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 20 (33.3) | |

| Rectum | 38 (63.3) | |

| 5. | Type of growth | |

| Constricting | 14 (23.3) | |

| Exophytic | 6 (10.0) | |

| Ulcerative | 40 (66.7) | |

| 6. | Growth palpable on PR examination | |

| Yes | 14 (23.3) | |

| No | 46 (76.7) | |

| 7. | Bleeding PR | |

| Yes | 32 (53.3) | |

| No | 28 (46.7) | |

| 8. | Lymph node exciseda | |

| D1 | 16.6 (16) (3–52) | |

| D2 | 8.1 (9.5) (1–16) | |

| D3 | 4.7 (3.0) (0–18) | |

| 9. | Lymph nodes positive on pathologya | |

| D1 | 3.9 (3.0) (0–17) | |

| D2 | 0.7 (0) (0–3) | |

| D3 | 0.1 (0) (0–1) | |

| 10. | Nodes positive on CT scan | 30 (50) |

| 11. | Method of lymph node excision | |

| High ligation | 44 (73.3) | |

| Low ligation | 16 (26.7) | |

| 12. | Number of lymph nodes exciseda | |

| By high ligation | 31.5 (33) (7–85) | |

| By low ligation | 25 (25) (17–36) | |

| Overall | 29.5 (30) (7–85) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless otherwise indicated

aValues are mean (median) (range)

Table 2.

Analysis of the distribution of variables according to the potential confounding factors

| Confounding factors | Variables | High ligation arm (%) N = 44 | Low ligation arm (%) N = 16 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 (72.7) | 12 (75.0) | 0.390 |

| Female | 12 (27.3) | 4 (25.0) | ||

| Age (years) | <20 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (6.2) | 0.711 |

| 21–40 | 8 (18.2) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| 41–60 | 26 (59.1) | 10 (62.5) | ||

| >60 | 9 (20.4) | 3 (18.8) | ||

| Site of primary | Descending colon | 1 (2.3) | 1 (6.2) | 0.383 |

| Sigmoid colon | 15 (34.1) | 5 (31.3) | ||

| Rectum | 28 (63.6) | 10 (62.5) | ||

| Nodes enlarged on CT scan | Yes | 23 (52.3) | 7 (43.7) | 0.226 |

| No | 21 (47.7) | 9 (56.2) |

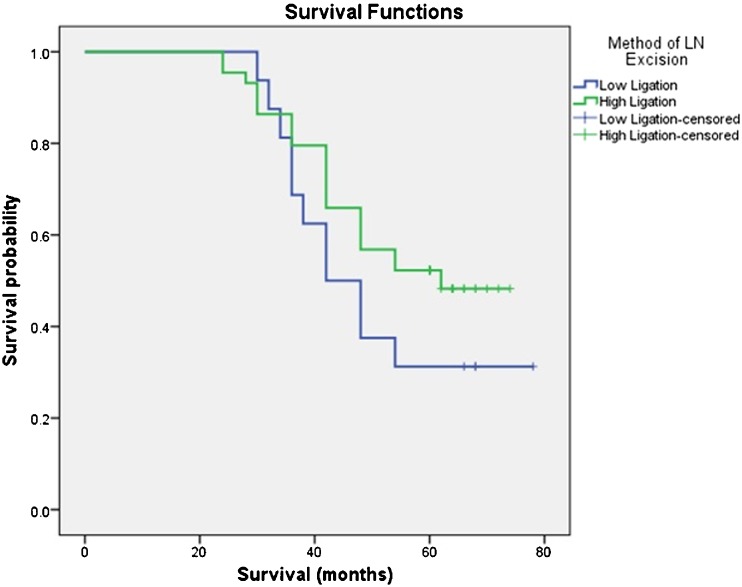

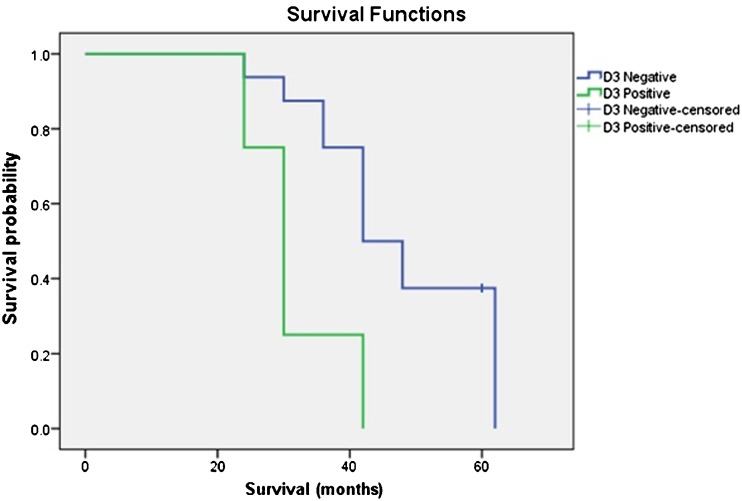

The follow-up of the patients were continued until December 2013. Median duration of follow-up for the survivors was 64 (60–78) months. There was a slight survival advantage when high ligation was compared with low ligation, median overall survival (OS) for high ligation being 62 months versus 42 months for low ligation; however, this data failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.190) (Fig. 1). Median OS for patients with positive D3 level nodes was 30 months [95 % confidence interval (CI) 15.6 to 44.4] while for negative D3 level, it was 54 months (p = 0.032) (Fig. 2). Finally, the data was sorted to include only D2-positive cases, and in this subgroup, survival for D3-positive versus D3-negative cases was analyzed. In this subgroup, median OS for patients with positive D3 level nodes was 30 months (95 % CI 24.9 to 35.1) while for negative D3 level, it was 42 months (95 % CI 34.1 to 49.8) (p = 0.011) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing overall survival in patients who underwent high ligation versus low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery. There was a slight survival advantage, median overall survival for high ligation being 62 months versus 42 months for low ligation; however, this data failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.190)

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing overall survival in patients who were pathologically D3 lymph nodes positive versus negative. Median OS for patients with positive D3 level nodes was 30 months while for negative D3 level, it was 54 months (p = 0.032)

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing overall survival in patients who were D2 node positive, comparing D3-positive versus D3-negative cases in this subgroup. Median OS for patients with positive D3 level nodes was 30 months while for negative D3 level, it was 42 months (p = 0.011)

The correlation between number of D2-positive nodes and number of D3-positive nodes was calculated. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.319 and the correlation was found to be significant (p = 0.013). The correlation between nodes positive on computed tomography (CT) scan and D1 node positivity was also significant (p < 0.001).

Discussion

There is no consensus for the level of lymph node dissection in left-sided colon and rectal cancers. The advocates of low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery believe that nodal involvement at high level is found only in patients with incurable cancer, and survival rates are not improved. In a study of more than 4,000 patients who underwent surgery for rectal carcinoma at St. Mark’s Hospital, no improved survival was seen when the inferior mesenteric artery was ligated above the origin of the left colic artery [5]. Ligation distal to the first branch of the inferior mesenteric artery ensures a viable blood supply to the bowel from which the stoma will be created. Corder et al. studied 143 consecutive patients but failed to show any association between the method of vascular ligation and the risk of tumor recurrence and death [6]. Furthermore, anastomotic leak rates were not related to the method of vascular ligation. The data from a French multicenter, randomized trial (comparing left colectomy and ligation of the IMA with segmental colectomy and ligation of the primary feeding vessel) show no statistically significant difference in long-term (12 years) survival [7].

Some studies have shown that high ligation may provide small survival benefit in selected subgroups of the patients. It also provides useful information for prognostic purpose. A large series from Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital (New York) showed improved survival only for patients with stage II rectal cancer who had high IMA ligation [8]. Stage III disease was not affected by high ligation at the IMA.

A more accurate staging and prognosis may be obtained by high ligation, but survival does not seem to be affected. Stage migration may affect overall outcome because of improved staging and lead time bias [9]. All lymph nodes suspicious for metastasis beyond the origin of the feeding vessel should have a biopsy or should be removed, or the level of resection should be extended to include the worrisome lymph nodes. Even so, a skip phenomenon (i.e., metastases beyond an uninvolved sentinel lymph node) should be present in only 5 % of cases [7].

In our series, lymph nodes could be visualized in 30 patients (50 %); on histological examination, 28 (93 %) showed malignant deposits. Two patients showing enlarged nodes on CT had only reactive changes pathologically. This finding may be attributed to the bare feet walking and minor repeated traumas in the people of low socioeconomic strata of India. In these cases, ligating the inferior mesenteric artery at its root and bringing down all the lymph nodes actually helped for proper staging of the patient, emphasizing the importance of the high ligation. Fourteen (23 %) patients having undetectable nodes on CT scan had micrometastasis suggesting low sensitivity of CT scan to detect nodal metastasis. Since there is no other method to reliably assess the nodal positivity [10], it is on oncologically safer side to remove all the lymph nodes.

There are few studies reporting survival or recurrence patterns in colorectal cancer patients with inferior mesenteric lymph node metastasis. Kanemitsu et al. reported that the 5- and 10-year survival rates of patients with metastases to D3 nodes were 40 and 21%, and those for patients with metastases to D2 nodes were 50 and 35%, respectively [11]. In our study, 5-year survival for patients with D2-positive nodes was 35% while no patient with D3-positive node could survive until 5 years. Thus, our data is in overall agreement with standard published studies. The poorer survival of D3-positive patients in our series could stem from smaller number of patients and more aggressive nature of disease in our patients.

Periarterial lymph node metastases requiring high ligation of the major arterial trunks and not the intramural spread dictates the extent of bowel that must be removed. Lymph node spread precedes venous spread, the determining factor being cellular activity of the lesion rather than its size. A plea is made for high ligation of the arterial trunks in order to allow for wide removal of the potential lymph node spread. The role of central vessels ligation in provision of optimal lymphovascular clearance was first identified about 100 years ago. Colonic lymph nodes follow the arterial supply, thus high ligation can remove the highest draining nodes that may harbor occult microscopic metastases. Enker et al. adhered to this principle strictly and reported 5-year disease-free survival rates of up to 70 % in stage III [6].

The Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum advocates mapping of the lymph node groups removed and would stamp as complete dissection of all regional nodes only if the specimen contained the D3 nodes [12]. Lymph node yields are dependent on both the surgeon and the pathologist, which could potentially influence the results in a two-center observational study. West et al. concluded that surgeons in Erlangen routinely practicing complete mesocolic excision (CME) and central vascular ligation (CVL) surgery remove more mesocolon and are more likely to resect in the mesocolic plane when compared with standard excisions. This, along with the associated greater lymph node yield, may partially explain the high 5-year survival rates reported in Erlangen [13]. There was an increase in the number of negative lymph nodes with CME and CVL which has been linked to improved survival in both lymph node negative cases [14, 15] and stage III disease [16]. West et al. reported a greater lymph node yield (median, 30 vs. 18; p < 0.0001) in high versus low ligation [13] In our study, the corresponding values are 33 and 25 (p = 0.048), thus establishing that high ligation produces oncologically superior specimen compared with standard low ligation surgery for carcinoma of the left colon and rectum. Japanese surgeons report overall 5-year survival rates of up to 76 % in stage III disease and produced similar lymph node yields to those seen in Erlangen, although stage migration may confound the results.

Limitations of the Study

As the study is observational, the patients were selected as per the surgeon’s choice. However, the selection bias is expected to be low as some surgeons in our hospital prefer high ligation in all the cases while the rest perform low ligation in all the cases, irrespective of the presentation of the patient, since there are no consensus guidelines on this issue.

Conclusions

High ligation of the IMA for rectal and left-sided colon cancers can improve lymph node yield, thus facilitating accurate tumor staging and thus better disease prognostication. Also, it can reduce the stage migration phenomenon, thus accurately predicting the outcome and can identify the cases that might require adjuvant chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Ishwar Charan and Akhil Kapoor contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

IC conceived the idea, formulated the study design, and participated in collecting the data. AK participated in writing the manuscript and performing literature search, data analysis, data interpretation, and statistical analysis. The rest of the authors participated in writing the manuscript and interpreting the data. All authors read the final manuscript and approved it.

Synopsis

This article compares high versus low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery in left colon and rectal cancer in terms of lymph node yield and survival benefit.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toms JR, editor. Cancer Stats Monograph 2004. London: Cancer Research UK; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, Couture J, Fleshman J, Guilllem J, Miedema B, Ota D, Sargent D. National Cancer Institute expert panel: guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:583–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moynihan BG. The surgical treatment of cancer of the sigmoid flexure and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1908;6:463–466. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surtees P, Ritchie JK, Phillips RK. High versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1990;77(6):618–621. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corder AP, Karanjia ND, Williams JD, Heald RJ. Flush aortic tie versus selective preservation of the ascending left colic artery in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:680–682. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouffet F, Hay JM, Vacher B, Fingerhut A, Elhadad A, Flamant Y, et al. Curative resection for left colonic carcinoma: hemicolectomy vs. segmental colectomy. A prospective, controlled, multicenter trial. French Association for Surgical Research. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:651–659. doi: 10.1007/BF02054407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slanetz CA, Grimson R. Effect of high and intermediate ligation on survival and recurrence rates following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1205–1218. doi: 10.1007/BF02055167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604–1608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makin GB, Breen DJ, Monson JRT. The impact of new technology on surgery for colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:612–621. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Komori K, Kato T. Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93(5):609–615. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (2009). Japanese classification of colorectal cancer (Kanehara & Co, Tokyo, Japan), ed 2, p 14

- 13.West N, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan P, Quirke P. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:272–278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2912–2919. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. More extensive nodal dissection improves survival for stages I to III of colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 2006;244:602–661. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237655.11717.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson PM, Porter GA, Ricciardi R, et al. Increasing negative lymph node count is independently associated with improved long-term survival in stage IIIB and IIIC colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3570–3575. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]