Abstract

The triatomines are vectors of the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. These insects are sexually active after the imaginal molt. Some aspects have been studied in Triatoma brasiliensis during the imaginal molt, such as autogeny in virgin females and the relationship between blood ingestion by fifth instar nymph and the realization of the imaginal molt. Thus, to aid in the understanding of reproductive biology and developmental physiology of these vectors, this article analyzes the spermatogenesis of T. brasiliensis during the imaginal molt. The analysis of the seminiferous tubules from males in the fifth instar during imaginal molt has demonstrated that T. brasiliensis has only a few spermatids and a plentiful quantity of sperm. Thus, we suggest that during imaginal molt the cell division is disrupted aiming to reduce energy costs and the differentiation into sperm is stimulated to ensure the paternity of the adult male.

Chagas disease is a potentially life-threatening illness caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and transmitted to humans by contact with feces of triatomine bugs, known as “kissing bugs.”1 These vectors have a typical hemimetabolous life cycle, from eggs through five nymphal instars (N1, N2, N3, N4, and N5) to adult males and females. The transition from the fifth instar nymph to adult is named imaginal molt. During this process it occur some corporal changes, such as the emergence of wings,2 exocrine glands (metasternal and Brindley's glands)3,4 and development of the reproductive system.5–8

Some aspects have been studied in Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 during the imaginal molt, such as autogeny in virgin females9 and the relationship between blood ingestion by N5 and the realization of the imaginal molt.10 This triatomine species is the most important Chagas disease vector in the Brazilian northeast.11,12 Thus, to aid in the understanding of the reproductive biology and developmental physiology of these vectors, this article analyzes the spermatogenesis of T. brasiliensis during the imaginal molt.

Five males in the fifth instar nymphs of T. brasiliensis were isolated and during imaginal molt their testicles were removed and fixed in methanol: acetic acid (3:1). They had been assigned by the “Triatominae Insectarium” within the Department of Biological Sciences, in the College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, at Sao Paulo State University's “Júlio de Mesquita Filho,” Araraquara campus. The colony was formed from T. brasiliensis collected in intradomiciliary region of the municipality Olho d'Água, State of Paraiba, Brazil in the day April 17, 2008.

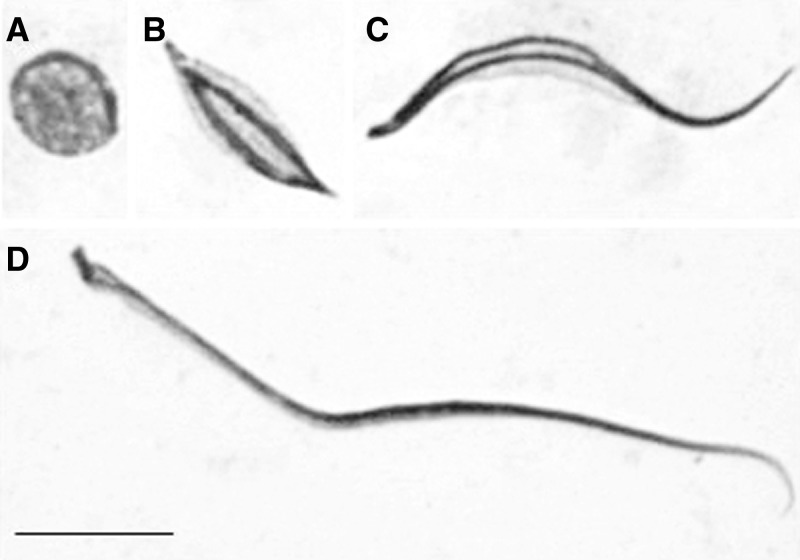

Seminiferous tubules were first shredded, smashed, and the microscope slides were set in liquid nitrogen. They were then stained with the lacto-acetic orcein cytogenetic technique.13,14 On the basis of the analysis of slides, it was observed that the N5 nymphs, during imaginal molt, have only one of the phases of spermatogenesis, that is, the spermiogenesis. This is represented by the presence of spermatids (Figure 1A –C) and sperm (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Spermiogenesis in Triatoma brasiliensis. Note the elongation of spermatids (A–C) and sperm (D). Bar: 10 μm.

Spermatogenesis is the process by which sperms are produced in the seminiferous tubules. It consists of three different phases: spermatocitogenesis, which is a phase of multiplication; meiosis, which is the division phase; and spermiogenesis, which is the differentiation phase.15

Perez and others,16 reported that in some cases fifth instar nymph have mature gonads. Mello and collaborators,17 analyzed fifth instar nymph of Triatoma infestans and observed the presence of spermatogonia, spermatocytes (metaphase), spermatids, and sperms. However, during imaginal molt of T. brasiliensis there are only a few spermatids and a plentiful quantity of sperm were observed, and we suggest that during imaginal molt, the cell division is disrupted aiming to reduce energy costs, and the differentiation into sperm is stimulated to ensure the paternity of the adult male.

There are some offensive mechanisms that increase the chances to ensure the paternity, such as the characteristics of the genitalia,18 the seminal fluid,19 and the courtship behavior.20 Taking it into account, we suggest that the excessive increase of sperms during imaginal molt also increase the chances for the paternity.

Thus, we suggest that during the imaginal molt T. brasiliensis showed changes in the reproductive biology of development and physiology to decrease the energy cost, ensuring that the molt occur and mainly to increase the chance of paternity in adults. These results provide important information for understanding the biology of this important vector of the Chagas disease. However, we highlight that new species and a larger number of triatomines should be analyzed to characterize whether this phenomenon occurs in all species of Triatominae subfamily.

Footnotes

Financial support: The study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (process numbers 2013/19764-0 - FAPESP, Brazil) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil).

Authors' addresses: Kaio Cesar Chaboli Alevi, Ana Letícia Guerra, Carlos Henrique Lima Imperador, and Maria Tercília Vilela de Azeredo-Oliveira, Departmento de Biologia, Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Rua Cristóvão Colombo, 2265, São José do Rio Preto, Brazil, E-mails: kaiochaboli@hotmail.com, analebio@yahoo.com.br, karlosimpe@gmail.com, and tercilia@ibilce.unesp.br. João Aristeu da Rosa, Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Rod. Araraquara-Jaú, Km 1 - Araraquara – SP, Araraquara, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: joaoaristeu@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Chagas Disease (American Trypanosomiasis) 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/ Available at. Accessed September 27, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rocha DS, Solano C, Jurberg J, Cunha V, Galvão C. Laboratory analysis of the flight of Rhodnius brethesi Matta, 1919, potential wild vector of Trypanosoma cruzi in the Brazilian Amazon. (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) Rev Pan-Amaz Saude. 2011;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schofield CJ, Upton CP. Brindley's scent-glands and the metasternal scent glands of Panstrongylus megistus (Hemiptera,Reduviidae, Triatominae) Rev Bras Biol. 1978;38:665–678. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossiter M, Staddon BW. 3-Methyl-2-hexanone from the bug Dipetalogaster maximus (Uhler) (Heteroptera; Reduviidae) Experientia. 1983;39:380–381. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumser JB, Davey KG. Endocrinological and other factors influencing testis development in Rhodnius prolixus. Can J Zool. 1974;52:1011–1022. doi: 10.1139/z74-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Rosa JA, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV. Spermatogenesis in Triatoma melanocephala (Hemiptera, Triatominae) Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:4944–4947. doi: 10.4238/2013.October.24.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alevi KC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Fernandes AL, da Rosa JA, de Azeredo-Oliveira MT. Analysis of spermiogenesis like a tool in the study of the triatomines of the Brasiliensis subcomplex. C R Biol. 2013;336:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Rosa JA, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV. Heteropyknotic filament in spermatids of Triatoma melanocephala and T. vitticeps (Hemiptera, Triatominae) Inv Rep Dev. 2013;58:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perondini ALP, Costa MJ, Brasileiro VLF. Biologia do Triatoma brasiliensis. II. Observações sobre autogenia. Rev Saude Publica. 1975;9:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brasileiro VLF, Perondini ALP. Biologia de Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae). IV – Parâmetros relacionados à muda imaginal. Rev Nord Biol. 1982;5:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa J, Almeida CE, Lins A, Vinhaes M, Silveira AC, Beard CB. The epidemiologic importance of Triatoma brasiliensis as a chagas disease vector in Brazil: a revision of domiciliary captures during 1993–1999. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:443–449. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alencar JE, Santos AR, Bezerra OF, Saraiva TM. Distribuição geográfica dos principais vetores de endemias no estado do Ceará. I - Triatomíneos. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1976;10:261–283. [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vaio ES, Grucci B, Castagnino AM, Franca ME, Martinez ME. Meiotic differences between three triatomine species (Hemiptera:Reduviidae) Genetica. 1985;67:185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Rosa JA, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV. Karyotype of Triatoma melanocephala Neiva and Pinto (1923). Does this species fit in the Brasiliensis subcomplex? Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1652–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Succi M, Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Bardella VB, Rosa JA, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV. Spermatogenesis in Triatoma williami Galvão, Souza and Lima (1965) (Hemiptera, Triatominae) Inv Rep Dev. 2014;58:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez R, Panzera Y, Scafiezzo S, Mazzella MC, Panzera F, Dujardin J, Scvortzoff E. Cytogenetics as a tool for Triatominae species distinction (Hemiptera-Reduviidade) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87:353–361. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761992000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mello MLS, Maria SS, Tavares MCH. Heat shock-induced apoptosis in germ line cells of Triatoma infestans Klug. Genet Mol Biol. 2000;23:301–304. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waage JK. Adaptive significance of postcopulatory guarding of mates and nonmates by male Calopteryx maculate (Odonata) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1979;6:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Civetta A. Direct visualization of sperm competition and sperm storage in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1999;9:841–844. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edvardsson M, Arnqvist G. Copulatory courtship and cryptic female choice in red flour beetles Tribolium castaneum. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:559–563. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]