Abstract

The treatment of pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus disease is associated with very high failure rates and easily acquired drug resistance. Amikacin is the key drug in treatment regimens, but the optimal doses are unknown. No good preclinical model exists to perform formal pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics experiments to determine these optimal doses. We developed a hollow-fiber system model of M. abscessus disease and studied amikacin exposure effects and dose scheduling. We mimicked amikacin human pulmonary pharmacokinetics. Both amikacin microbial kill and acquired drug resistance were linked to the peak concentration-to-MIC ratios; the peak/MIC ratio associated with 80% of maximal kill (EC80) was 3.20. However, on the day of the most extensive microbial kill, the bacillary burden did not fall below the starting inoculum. We performed Monte Carlo simulations of 10,000 patients with pulmonary M. abscessus infection and examined the probability that patients treated with one of 6 doses from 750 mg to 4,000 mg would achieve or exceed the EC80. We also examined these doses for the ability to achieve a cumulative area under the concentration-time curve of 82,232 mg · h/liter × days, which is associated with ototoxicity. The standard amikacin doses of 750 to 1,500 mg a day achieved the EC80 in ≤21% of the patients, while a dose of 4 g/day achieved this in 70% of the patients but at the cost of high rates of ototoxicity within a month or two. The susceptibility breakpoint was an MIC of 8 to 16 mg/liter. Thus, amikacin, as currently dosed, has limited efficacy against M. abscessus. It is urgent that different antibiotics be tested using our preclinical model and new regimens developed.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium abscessus is a rapidly growing mycobacterium (RGM) responsible for about 80% of all pulmonary infections caused by RGM (1). It is one of the most drug-resistant microorganisms encountered in the clinic, far worse than extensively and totally drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis; this is a reason why it is considered the “new antibiotic nightmare” (2). The current treatment for M. abscessus diseases varies according to the infecting subspecies (3); in general, it involves a backbone of amikacin in combination with clarithromycin and either cefoxitin or imipenem early during therapy, followed by subsequent use of oral antibiotics, which is analogous to the initial and continuation phases of tuberculosis treatment (1). Unfortunately, at least half of the patients either fail this therapy, relapse, or die; there is no reliable antibiotic regimen that cures M. abscessus lung disease (1, 4). Several other regimens have been tried and found wanting. In such regimens and the standard regimen, the doses were chosen based on what has worked well in mundane Gram-negative bacilli. No formal antimicrobial pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses have been performed with M. abscessus. Our time-kill assays in the past demonstrated that amikacin was the most active antibiotic compared to cefoxitin and clarithromycin (5). Here, we performed formal PK/PD studies of amikacin, which is considered the most active parenteral antibiotic against M. abscessus, according to treatment guidelines (1).

Recent attempts to evaluate antibiotics and regimens in preclinical M. abscessus disease models have included the use of Drosophila melanogaster and zebra fish (6, 7). However, a tractable model in which PK/PD experiments can be performed still needs to be developed. Here, we adapted the hollow-fiber system models (HFS) of slower-growing mycobacteria (8–11) and developed a novel PK/PD system for M. abscessus pulmonary disease in order to identify the amikacin exposures and dose schedules associated with optimal microbial kill and suppression of acquired drug resistance (ADR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and drugs.

M. abscessus ATCC 19977 (American Type Culture Collection) was used as the test strain. Stock cultures of the mycobacteria were preserved at −80°C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) and 15% glycerol. For each assay, one vial was thawed and incubated for 24 to 48 h at 30°C to achieve logarithmic-growth phase. Amikacin sulfate powder for intravenous administration was purchased from the Baylor University Medical Center pharmacy (Dallas, TX) and then diluted in sterile water to desired concentrations for the assays. Apramycin was purchased from Sigma.

MIC and mutation frequency.

Broth macrodilution in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (here termed “broth”) was used to identify the MIC (12). In addition to the turbidity test, the CFU per milliliter were enumerated for each concentration evaluated in the broth macrodilution test, and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration associated with ≥99% inhibition of growth. The Etest (bioMérieux) on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (here termed “agar”) was also used as a screening test when an MIC evaluation was needed for HFS liquid cultures. Mutation frequency was determined for the inoculum by culturing 0.2 ml each on 20 agar plates supplemented with 3 times the amikacin MIC. This concentration was chosen since 3 times the MIC is the lowest fold change associated with efflux pump-related resistance in other mycobacteria (13).

Concentration-effect studies in test tubes.

M. abscessus was grown in broth in log phase to the equivalent of a 0.5 McFarland standard turbidity based on optical density measurements at 600 nm, and it was then back-diluted to reach a bacterial density of approximately 106 log10 CFU/ml. M. abscessus was exposed to amikacin concentrations of 0, 1/8, 1/4, 1/2,1, 2, 4, and 8 times the MIC at 30°C in test tubes. After 72 h of incubation, the contents of each tube were washed with saline and then serially diluted and cultured on agar at 30°C in order to enumerate the CFU per milliliter. The inhibitory sigmoid maximum effect (Emax) model was used to identify the relationship between amikacin concentration and M. abscessus CFU per milliliter.

Hollow-fiber model for M. abscessus.

The HFS model has two physical compartments: the central compartment, in which drug circulates, and the peripheral compartment, which houses the mycobacteria (8). The peripheral compartment is separated from the central compartment by the semipermeable hollow fibers with a pore size of 42 kDa, through which fresh medium (broth with 10% dextrose) circulates. Thus, the concentrations of chemicals in the peripheral compartment are in equilibrium with the central compartment. Twenty milliliters of 106 log10 CFU/ml log-phase M. abscessus cells were inoculated into the peripheral compartment of each cellulosic hollow-fiber cartridge (FiberCell Systems). M. abscessus cells are much larger than the pores and thus stay confined to the peripheral compartment, where they are continuously bathed by dynamic concentrations of chemicals and drugs. All systems were permanently kept in a 30°C incubator.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study.

Twelve HFS were inoculated with M. abscessus, as described above. For the dose-effect experiments, amikacin doses that mimic the serum area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) and peak concentrations (Cmax) achieved in humans exposed to human-equivalent doses of 66.7, 125, 250, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 4,000, and 6,400 mg were administered once daily to the central compartment via computerized syringe pumps. Dose-scheduling studies were simultaneously performed; we tested human-like doses of 500, 2,000, and 4,000 mg, chosen based on the pilot concentration-effect study in test tubes, to be administered thrice daily in order to match some of the Cmax/MIC and percent time the concentration remains above the MIC (%TMIC) in the once-a-day regimens. The dilution rates were set to achieve an amikacin half-life of 3 h, as encountered in serum and bronchial secretions (14, 15). The amikacin concentrations achieved in all the HFS were validated by sampling each central compartment during the last 2 days at 0, 0.5, 2.7, 5.4, 18.7, 23.5, 24.5, 26.7, 29.4, 42.7, and 47.5 h after the drug administration; the sampling times were chosen based on optimal sampling theory for the pharmacokinetics of amikacin (16–18). In order to quantify the M. abscessus CFU per milliliter, 1 ml of the peripheral compartment contents was removed from each system on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14. The samples were washed with saline to avoid antibiotic carryover, after which samples were serially diluted and cultured on agar. To quantify the amikacin-resistant M. abscessus CFU per milliliter, the same samples were also inoculated on agar supplemented with 3 times the amikacin MIC.

Drug assay.

Apramycin was used as the internal standard. Calibrator, controls, and apramycin were included in each analytical run for quantitation. Stock solutions of amikacin and apramycin were prepared in 80:20 methanol-water at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −20°C. An eight-point calibration curve was prepared by diluting the amikacin stock solution in drug-free broth (1, 2, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg/ml). Quality control samples were prepared by spiking media with stock standards for two levels of controls. Samples were prepared in 96-well microtiter plates, 10 μl of calibrator, quality controls, or sample was added to 190 μl of 0.1% formic acid in water containing 10 μg/ml apramycin, and the samples were vortexed. Chromatographic separation was achieved on an Acquity ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) high-strength silica (HSS) T3, 1.8 μm, 50 by 2.1-mm analytical column (Waters) maintained at 30°C at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, with a binary gradient and a total run time of 6 min. The observed ion (m/z) values of the fragment ions were amikacin (m/z 586→425) and apramycin (m/z 540→378). Sample injection and separation were performed using an Acquity UPLC interfaced with a Xevo TQ mass spectrometer (Waters). All data were collected using MassLynx version 4.1 SCN810. The limit of quantitation for this assay was 0.5 μg/ml.

Pharmacokinetic and PK/PD modeling.

The drug concentrations from each HFS were comodeled as a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model, a two-compartment model, and a three-compartment model using the ADAPT 5 program (19). The best model was chosen using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and parsimony (20, 21). The pharmacokinetic parameter estimates were then used to calculate the observed AUC0–24, the AUC0–24/MIC ratio, and %TMIC. The observed Cmax in each HFS was used to calculate the Cmax/MIC. Dose response was modeled using the inhibitory sigmoid Emax model with the total bacterial burden used as the response parameter, while drug exposure was expressed as either the AUC0–24/MIC ratio, %TMIC, or Cmax/MIC ratio. However, the development of drug resistance is not in accordance with the inhibitory sigmoid Emax model but rather an integrated quadratic model, which was used to identify the relationship between drug exposure and the amikacin-resistant subpopulation (22–25).

Translation from the hollow-fiber model to clinical doses.

In order to translate from the HFS to the bedside, we performed computer-aided clinical trial simulations based on Monte Carlo experiments, according to the steps outlined in the recent recommendations for academia and industry (24). The population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates we used and the covariance were from a study by Delattre et al. (18) of 88 Belgian patients. This study was chosen because of the rigorous use of optimal sampling theory, which minimizes bias and inaccuracies in identifying pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. The pharmacokinetic parameters used as the domain of input in subroutine PRIOR of ADAPT are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. First, Monte Carlo simulations were performed to identify the Cmax, AUC0–24, and concentration-time profiles achieved by doses of 750, 1,000, 1,500, 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 mg in 10,000 patients. Since at steady state with once-a-day dosing in patients with pneumonia, peak concentrations in bronchial secretion are only 40.5% of those in serum, and the AUC0–24 is only 81% of those in serum, these penetration ratios into the lung were taken into account (15). Next, we introduced the effect of MIC variability, based on the MICs identified in 44 patients seen by one of us (J.V.I.) with M. abscessus pulmonary disease at Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. The probability of achieving the EC80 exposure Cmax/MIC ratio, or target attainment probability, at each MIC was then calculated. The results were then used to calculate the cumulative fraction of response. Exposure associated with toxicity in patients was also calculated for different doses, based on exposures we have identified as causing ototoxicity in amikacin-treated patients who had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, in which a cumulative AUC0–24 of 82,232 mg · h/liter × days predicts amikacin ototoxicity (17).

RESULTS

The amikacin MIC for the M. abscessus laboratory strain was 32 mg/liter by all methods, on repeat analysis. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), which is the concentration associated with >99.9% kill, was 64 mg/liter, so that the MBC/MIC ratio was 2, making amikacin a bactericidal agent by standard definitions (26). The mutation frequency to 3 times the amikacin MIC was 2.73 ± 0.31 × 10−6 in repeat experiments.

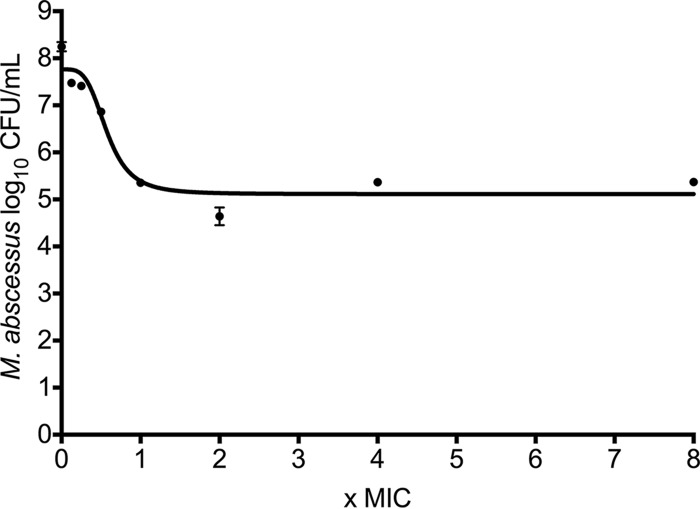

The relationship between amikacin concentration as a multiple of the MIC and microbial burden after 3 days of incubation in test tubes is shown in Fig. 1. This experimental design, which uses static concentrations of amikacin, was associated with a maximum effect (Emax) of 2.65 log10 CFU/ml (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.26 to 3.04 log10 CFU/ml), a Hill slope (H) of 3.88 (95% CI,1.13 to 6.63), and a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 0.57 times the MIC (95% CI, 0.46 to 0.69 times the MIC) (r2 = 0.93). Figure 1 shows that the bacterial burden at the Emax was 5.12 log10 CFU/ml, which is >1.0 log10 CFU/ml less than the bacterial burden of 6.13 log10 CFU/ml at the beginning of incubation, with just 3 days of incubation with static amikacin concentrations. This magnitude of microbial kill is consistent with the notion that amikacin is very active against M. abscessus.

FIG 1.

Amikacin concentration-effect response in test tubes. The graph shows impressive microbial kill after 3 days of incubation in test tubes. Surprisingly, the pattern of microbial kill, characterized by maxing out at 2 to 4 times the MIC, would be more consistent with time-dependent killing instead of concentration-dependent killing.

Next, we performed HFS studies that used dynamic concentrations of amikacin, and we comodeled the 121 amikacin concentrations that were measured in all the HFS. The concentrations were best described by a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model, which was characterized by a total clearance of 1.5 liters/h, volume of central compartment of 7.98 liters, intercompartmental clearance of 22.3 liters/h, and a peripheral volume of 0.04 liters, which are virtually similar to those parameters in patients treated with amikacin (17).

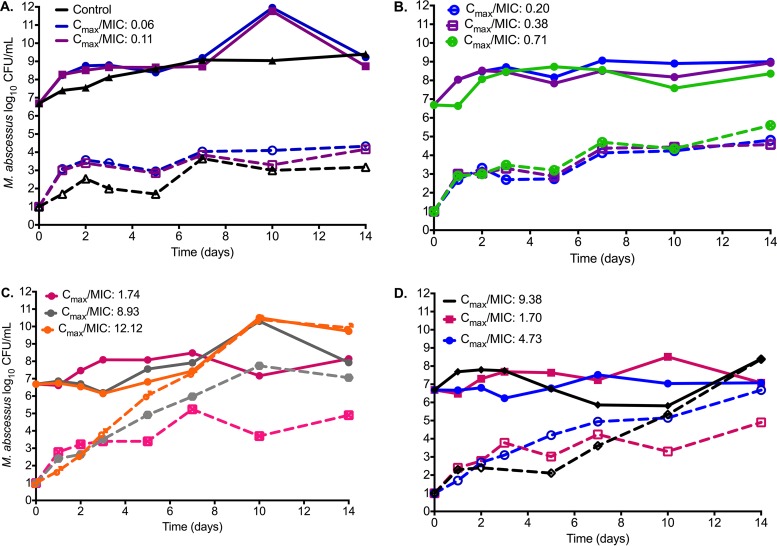

The day 0 bacterial burden in the HFS (i.e., just prior to start of therapy) was 6.69 log10 CFU/ml. The changes in total bacterial burden and the amikacin-resistant subpopulation for each drug exposure are shown in Fig. 2. The figure shows that the amikacin efficacy (i.e., Emax) was minimal. By day 3, the bacterial burden at the Emax was only 0.50-log10 CFU/ml lower than starting bacterial burden, which is considerably lower than that with static concentrations. Figure 2 also shows that amikacin microbial kill was effectively terminated by day 5, and starting on day 7, the overall bacterial burden had begun to reflect the replacement of the total population by the amikacin-resistant subpopulation. We performed an Etest at the beginning and end of the experiments, and as shown in Fig. 2C and D, there was a change in the MIC in the two highest concentration treatments, from 32 to >256 mg/liter on both the once-a-day and three-times-a-day treatment schedules.

FIG 2.

Changes in bacterial burden and amikacin-resistant subpopulation with time. (A to D) The total M. abscessus population (solid lines) and amikacin-resistant subpopulation (dashed lines) over the course of 14 days of exposure to different Cmax/MIC exposures are shown. There was a higher amikacin-resistant subpopulation of M. abscessus as the Cmax/MIC increased, so that at higher Cmax/MIC ratios (C and D), the total population had been completely replaced by the amikacin-resistant subpopulation by day 14.

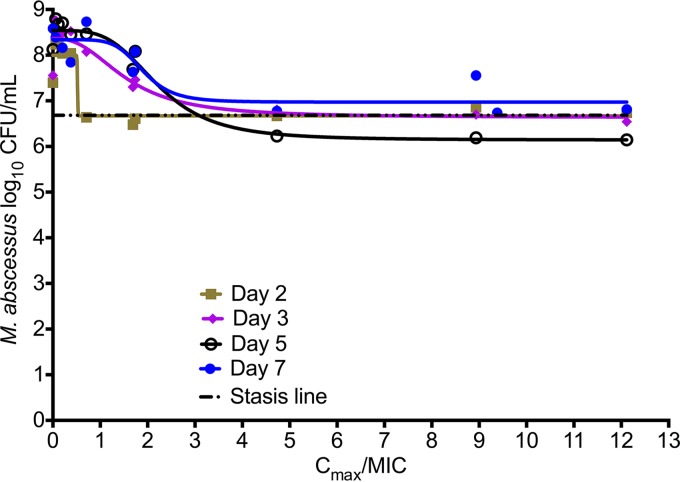

Inhibitory sigmoid Emax models for microbial kill up to 7 days, using either observed Cmax/MIC, AUC/MIC, or %TMIC, revealed the Akaike information criterion (AIC) scores shown in Table 1. The lowest AIC score was for Cmax/MIC for all days up to day 5. If one simply used the r2 for model fit, the r2 values were highest for Cmax/MIC up to day 5. It should be noted that while the day 7 results seemed to indicate the lowest AIC score for %TMIC, the result was judged to be spurious, since the EC50 exceeded the possible extrema of the %TMIC function; in this case, the maximum possible %TMIC of 100% was exceeded by the EC50. Taken together, amikacin efficacy was primarily driven by Cmax/MIC ratios, which had the lowest AIC scores for up to 5 days, beyond which the total population was replaced by drug-resistant subpopulation in some systems. The relationship between the Cmax/MIC ratio and bacterial burden on day 5 is shown in Fig. 3. The relationship was characterized by Emax of 2.40 ± 0.22 log10 CFU/ml, a Hill slope of 3.79 ± 2.44, and an EC50 that was a Cmax/MIC of 2.22 ± 0.44 (r2 = 0.97). Thus, the EC50 is considerably higher than that in the static amikacin concentration experiments (Fig. 1), while the H is virtually identical. The EC80, which is considered the optimal exposure, was a Cmax/MIC ratio of 3.20.

TABLE 1.

Akaike information criterion scores for PK/PD indices linked to microbial kill

| PK/PD parameter | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % time above MIC | 3.272 | No convergence | −0.7837 | −4.925 |

| AUC/MIC | −5.173 | −1.303 | 3.955 | −0.9094 |

| Cmax/MIC | −5.173 | −2.244 | −14.56 | −3.525 |

FIG 3.

Amikacin exposure effect in the hollow-fiber system. The results are shown up to day 7, at which point the drug-resistant subpopulation had begun to replace the total population in some systems. This is reflected by the increase in Emax each day until day 5, after which it began to decline. At the maximal microbial kill, the bacterial burden barely fell below the stasis line, suggesting that in fact amikacin is not bactericidal in the hollow-fiber system.

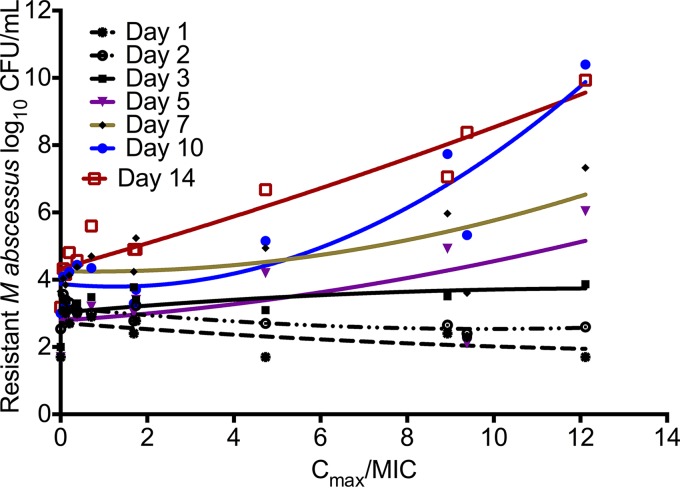

Table 2 shows the AIC for Cmax/MIC, %TMIC, and AUC/MIC versus the amikacin-resistant subpopulation modeled on the quadratic function for drug resistance. While the quadratic function for resistance emergence (22–25) is integrated over time, we utilized piecewise functions for each day of sampling, since we have found that PK/PD indices “wobble” with the duration of therapy (27). Table 2 shows the same wobble phenomenon, and that the PK/PD index associated with the size of the amikacin-resistant subpopulation during the first 3 days was %TMIC; by day 14, this had changed to Cmax/MIC. Figure 4 shows a system of inverted “U” curves during the first 2 days, with a switch to a straight line on day 3, followed by “U” curves from day 3 onwards. The day 14 relationship between Cmax/MIC and the amikacin-resistant subpopulation was described by log10 CFU/ml = 4.333 + 0.364 × (Cmax/MIC) + 0.006 × (Cmax/MIC)2; r2 = 0.906. This means that by day 14, there was no amikacin concentration that could reduce the size of the drug-resistant subpopulation to the 3.8 log10 CFU/ml encountered in nontreated controls.

TABLE 2.

Akaike information criterion scores for PK/PD indices linked to acquired resistance

| PK/PD parameter | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 10 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % time above MIC | −8.984 | −19.28 | −0.7686 | 11.37 | 10.44 | 19.89 | 11.27 |

| AUC/MIC | −6.262 | −16.93 | 0.5867 | 5.903 | 1.006 | 1.087 | 7.316 |

| Cmax/MIC | −7.126 | −18.72 | 0.1416 | 9.673 | 6.695 | 7.812 | 0.2809 |

FIG 4.

Amikacin-resistant subpopulation evolution with duration of treatment. The curves for each day are piecewise for the U-shaped relationship between exposure versus size of the drug-resistant subpopulation. With increasing time, the baseline amikacin-resistant subpopulation in the absence of drug exposure grows so that curves start at a different y intercept on each day. For days 1 and 2, the curve shape is an inverted U curve; at day 3, it is a straight line, and then it switches to an upright “U.” However, by day 14, the right side of the curve has straightened out, which means that there was no amikacin Cmax/MIC ratio high enough to reduce the size of the drug-resistant subpopulation, and the curve is no longer a “U.”

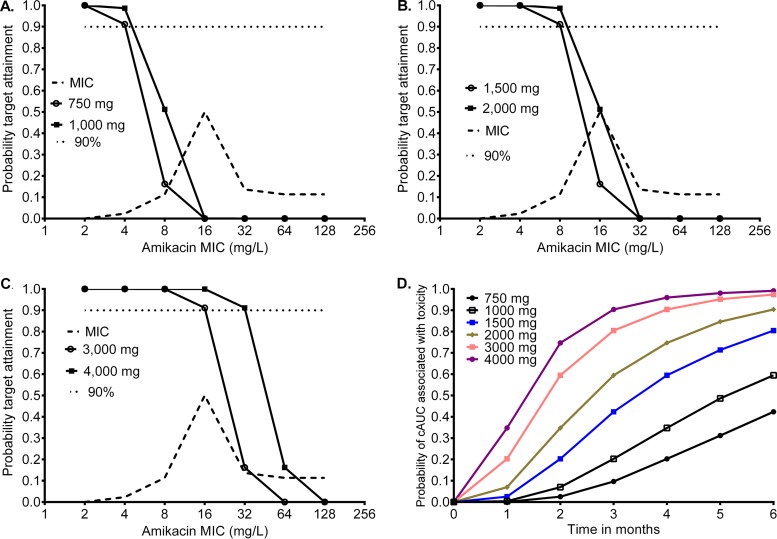

To translate our HFS findings to the clinic, we performed Monte Carlo simulations to identify the probability that different amikacin doses could achieve or exceed the EC80 exposure Cmax/MIC ratio of 3.2. The MIC distribution in 44 clinical isolates used in the simulations is shown in Fig. 5; the median MIC was 16 mg/liter (range, 4 to 128 mg/liter). Figure 5A and B show the proportions of patients treated with doses of 750, 1,000, and 1,500 mg who achieved this target exposure, which give cumulative response percentages of 3.94%, 8.41%, and 20.77% of patients, respectively. Figure 5B and C also show target attainment by the higher doses of 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 mg, for which the cumulative response fractions were 39.21%, 61.43%, and 70.05%, respectively. This means that none of the doses tested would achieve or exceed the EC80 in >90% of the patients, which is considered an adequate proportion of patients in other mycobacterial infections. Figure 5A and B also illustrate the MIC below which there is reduced microbial kill in at least 10% of patients with the standard dose, which is 8 mg/liter, while Fig. 5B and C show that with higher doses of ≥2,000 mg, this is 16 mg/liter. Thus, the resistance breakpoint drug concentration in Middlebrook broth would be set at 16 mg/liter at the most, and it should be considered that beyond this MIC, patients will not have good responses unless the dose is increased. However, such dose increases would increase the chances of toxicity. As an example, the duration of therapy and a cumulative AUC0–24 of 82,232 mg · h/liter × days predict amikacin ototoxicity, and Fig. 5D shows the probability of achieving that threshold concentration associated with an increased risk of ototoxicity for the six different daily doses. There is a rapid increase in odds of deafness at doses of 3,000 to 4,000 mg a day.

FIG 5.

Probability target attainment of different amikacin doses in 10,000 patients. (A) At doses of 750 mg and 1,000 mg, which are standard doses, there was very poor target attainment at the most commonly encountered MICs. The target attainment fell below 90% at the 8 mg/liter MIC. (B) At doses of 1,500 mg to 2,000 mg, <90% of the patients achieved the target Cmax/MIC after the MIC of 8 mg/liter. At a dose of 15 mg/kg of body weight, patients weighing up 100 kg would have 1,500 mg as normal dose, while the 2,000-mg dose is higher than currently administered. (C) Doses of 3,000 mg and 4,000 mg would better attain target concentrations, but even at these high doses, target attainment falls below 90% at an MIC of 32 mg/liter. (D) Probability of ototoxicity in 10,000 patients exposed to different amikacin concentrations for different durations of therapy, indicating a rapid increase in the odds of attaining toxic cumulative AUCs (cAUC) with just 2 months of therapy for doses of ≥2,000 mg.

DISCUSSION

Amikacin has long been considered the most active parenteral antibiotic against M. abscessus (1). We found that while models of static concentrations suggested that it is a bactericidal drug with time-driven efficacy, they overestimated amikacin efficacy compared to that in the HFS model. The HFS model's poor amikacin efficacy correlates better with clinical observations of amikacin-containing regimens in the antibiotic treatment of pulmonary M. abscessus, which entail high failure rates, “the talking M. abscessus blues” (28, 29). We found that both optimal amikacin microbial kill and ADR were associated with the Cmax/MIC ratio; for ADR, however, the PK/PD response parameter was %TMIC in the first 3 days but changed to Cmax/MIC beyond day 3. The optimal Cmax/MIC ratio for microbial kill was 3.2, which is considerably lower than the Cmax/MIC of 8 to 12 identified for mundane bacteria (30, 31). However, we show that even for that relatively lower Cmax/MIC ratio, the standard amikacin doses failed to achieve the target in more than three-quarters of patients, and much higher intravenous doses would need to be administered to even achieve the target in >70% of patients. In any case, this EC80 target would merely hold bacterial burden constant at best, which is just “cuddling” the bacteria, while with the higher doses, the patients would pay with a high risk of deafness. Alternative delivery methods, such as the use of inhaled liposomal amikacin, could overcome this: the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of daily dosing of 590 mg of liposomal amikacin for inhalation versus placebo in patients with recalcitrant nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease are currently being assessed (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01315236). However, by definition, even such delivery methods would not have a higher Emax, so that effect would still be compromised. Regardless, our findings mean that the role of intravenous amikacin in the current regimens used for pulmonary M. abscessus should be revisited and perhaps be replaced by more-active antibiotics.

Current M. abscessus regimens are partly guided by in vitro results, but the clinical correlation is lacking. The existing susceptibility breakpoint for amikacin, tested in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton medium, is ≥64 mg/liter (12). However, this breakpoint has failed to discriminate patients who would respond to therapy. Based on HFS findings and Monte Carlo simulations, we propose a breakpoint of 16 mg/liter in Middlebrook broth. The poor correlation observed between in vitro tests and patient outcomes might be explained by this discrepancy, since most isolates would be considered resistant based on this proposed breakpoint. While these are merely simulations of a single agent used in combination therapy in real life, experience with antituberculosis drugs has demonstrated that such HFS- and Monte Carlo simulation-derived breakpoints for monotherapy are highly accurate in predicting the breakpoints above which therapy fails that are actually observed in the clinic in combination therapy studies (32–36). Thus, our results will likely be borne out in the clinic setting in the future.

Finally, our new HFS model of M. abscessus disease is a tractable model that can be used to study the roles of other antibiotics, both as monotherapy and as combination therapy. The model allows repetitive sequential sampling in the same system of bacterial cultures and drug concentrations, which let us follow the evolution of the bacteria when exposed to different treatment regimens. This approach, which is not possible with animal models, for which harvesting of lungs is a terminal procedure, or with fruit flies, permits more powerful statistical computations, such as time-to-event analyses, repeated-measures analyses, and construction of systems equations for phenomena, such as resistance emergence.

Our study has some limitations. First, we examined only the effect of amikacin alone. Amikacin is used in combination with other antibiotics in patients. However, for optimal combination regimen design, it was necessary to start with the optimization of each component of the regimen as monotherapy for those combinations in which the drugs are additive. In the case of a synergistic combination, it may be possible to achieve more microbial kill without optimization of the combination. Second, we show the results of an HFS model for extracellular infection. However, M. abscessus, like all mycobacteria, is both an extracellular and intracellular pathogen. Nevertheless, amikacin does not kill intracellular bacteria due to only 5% penetration into macrophages (37), so amikacin efficacy might be worse than what we observed. We have intracellular HFS models of M. abscessus, which we will use to study those agents that are active intracellularly. Third, we report results with one M. abscessus strain. A larger number of isolates would give a more robust EC80 target (38); this, however, is limited by costs associated with performing each HFS study.

In summary, we developed a preclinical model for M. abscessus disease in which we identified the low efficacy of intravenous amikacin. The model will be useful for understanding the efficacy and ADR during the treatment of M. abscessus infection, dose-ranging and dose-scheduling studies, and the design of new and more-effective combination regimens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R56 AI111985 to T.G.) and a doctoral fellowship from the Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología Francisco José de Caldas (COLCIENCIAS) to B.E.F.

T.G. is a consultant for Astellas Pharma USA and LuminaCare solutions; he founded Jacaranda Biomed, Inc.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02282-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K, ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nessar R, Cambau E, Reyrat JM, Murray A, Gicquel B. 2012. Mycobacterium abscessus: a new antibiotic nightmare. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:810–818. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Ingen J, Ferro BE, Hoefsloot W, Boeree MJ, van Soolingen D. 2013. Drug treatment of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in HIV-negative patients: the evidence. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 11:1065–1077. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.830413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarand J, Levin A, Zhang L, Huitt G, Mitchell JD, Daley CL. 2011. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis 52:565–571. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferro BE, van Ingen J, Wattenberg M, van Soolingen D, Mouton JW. 2015. Time-kill kinetics of antibiotics active against rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:811–817. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernut A, Le Moigne V, Lesne T, Lutfalla G, Herrmann JL, Kremer L. 2014. In vivo assessment of drug efficacy against Mycobacterium abscessus using the embryonic zebrafish test system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4054–4063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00142-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh CT, Moon C, Jeong MS, Kwon SH, Jang J. 2013. Drosophila melanogaster model for Mycobacterium abscessus infection. Microbes Infect 15:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava S, Gumbo T. 2011. In vitro and in vivo modeling of tuberculosis drugs and its impact on optimization of doses and regimens. Curr Pharm Des 17:2881–2888. doi: 10.2174/138161211797470192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande D, Srivastava S, Meek C, Leff R, Gumbo T. 2010. Ethambutol optimal clinical dose and susceptibility breakpoint identification by use of a novel pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model of disseminated intracellular Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1728–1733. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01355-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumbo T, Louie A, Deziel MR, Parsons LM, Salfinger M, Drusano GL. 2004. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J Infect Dis 190:1642–1651. doi: 10.1086/424849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasipanodya JG, Nuermberger E, Romero K, Hanna D, Gumbo T. 2015. Systematic analysis of hollow fiber model of tuberculosis experiments. Clin Infect Dis 61(Suppl 1):S10–S17. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard M24-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmalstieg AM, Srivastava S, Belkaya S, Deshpande D, Meek C, Leff R, van Oers NS, Gumbo T. 2012. The antibiotic resistance arrow of time: efflux pump induction is a general first step in the evolution of mycobacterial drug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4806–4815. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05546-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dull WL, Alexander MR, Kasik JE. 1979. Bronchial secretion levels of amikacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 16:767–771. doi: 10.1128/AAC.16.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santré C, Georges H, Jacquier JM, Leroy O, Beuscart C, Buguin D, Beaucaire G. 1995. Amikacin levels in bronchial secretions of 10 pneumonia patients with respiratory support treated once daily versus twice daily. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:264–267. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam VH, Preston SL, Drusano GL. 2003. Optimal sampling schedule design for populations of patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2888–2891. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2888-2891.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modongo C, Pasipanodya JG, Zetola NM, Williams SM, Sirugo G, Gumbo T. 2015. Amikacin concentrations predictive of ototoxicity in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6337–6343. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01050-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delattre IK, Musuamba FT, Nyberg J, Taccone FS, Laterre PF, Verbeeck RK, Jacobs F, Wallemacq PE. 2010. Population pharmacokinetic modeling and optimal sampling strategy for Bayesian estimation of amikacin exposure in critically ill septic patients. Ther Drug Monit 32:749–756. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181f675c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Argenio DZ, Schumitzky A, Wang X. 2009. ADAPT 5 user's guide: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Biomedical Simulations Resource, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA: https://bmsr.usc.edu/files/2013/02/ADAPT5-User-Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akaike H. 1974. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 19:716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludden TM, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. 1994. Comparison of the Akaike information criterion, the Schwarz criterion and the F test as guides to model selection. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 22:431–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02353864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gumbo T, Louie A, Liu W, Brown D, Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, Drusano GL. 2007. Isoniazid bactericidal activity and resistance emergence: integrating pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics to predict efficacy in different ethnic populations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2329–2336. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00185-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gumbo T, Dona CS, Meek C, Leff R. 2009. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of pyrazinamide in a novel in vitro model of tuberculosis for sterilizing effect: a paradigm for faster assessment of new antituberculosis drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3197–3204. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01681-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumbo T, Angulo-Barturen I, Ferrer-Bazaga S. 2015. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic and dose-response relationships of antituberculosis drugs: recommendations and standards for industry and academia. J Infect Dis 211(Suppl 3):S96–S106. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gumbo T. 2008. Integrating pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics to predict outcomes in antibacterial therapy. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 11:32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pankey GA, Sabath LD. 2004. Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis 38:864–870. doi: 10.1086/381972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musuka S, Srivastava S, Siyambalapitiyage Dona CW, Meek C, Leff R, Pasipanodya J, Gumbo T. 2013. Thioridazine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters “wobble” during treatment of tuberculosis: a theoretical basis for shorter-duration curative monotherapy with congeners. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5870–5877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00829-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith DE. 2011. The talking Mycobacterium abscessus blues. Clin Infect Dis 52:572–574. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Ingen J, Egelund EF, Levin A, Totten SE, Boeree MJ, Mouton JW, Aarnoutse RE, Heifets LB, Peloquin CA, Daley CL. 2012. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:559–565. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, Rubino CM, Louie A, Gumbo T, Forrest A, Drusano GL. 2007. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: it's not just for mice anymore. Clin Infect Dis 44:79–86. doi: 10.1086/510079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craig WA, Redington J, Ebert SC. 1991. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in mouse thigh and lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 27(Suppl C):29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gumbo T. 2010. New susceptibility breakpoints for first-line antituberculosis drugs based on antimicrobial pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic science and population pharmacokinetic variability. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1484–1491. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01474-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gumbo T, Chigutsa E, Pasipanodya J, Visser M, van Helden PD, Sirgel FA, McIlleron H. 2014. The pyrazinamide susceptibility breakpoint above which combination therapy fails. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2420–2425. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gumbo T, Pasipanodya JG, Wash P, Burger A, McIlleron H. 2014. Redefining multidrug-resistant tuberculosis based on clinical response to combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6111–6115. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03549-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ocheretina O, Escuyer VE, Mabou MM, Royal-Mardi G, Collins S, Vilbrun SC, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. 2014. Correlation between genotypic and phenotypic testing for resistance to rifampin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Haiti: investigation of cases with discrepant susceptibility results. PLoS One 9:e90569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gumbo T, Pasipanodya JG, Romero K, Hanna D, Nuermberger E. 2015. Forecasting accuracy of the hollow fiber model of tuberculosis for clinical therapeutic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 61(Suppl 1):S25–S31. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rey-Jurado E, Tudo G, Soy D, Gonzalez-Martin J. 2013. Activity and interactions of levofloxacin, linezolid, ethambutol and amikacin in three-drug combinations against Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in a human macrophage model. Int J Antimicrob Agents 42:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacGowan AP, Reynolds R, Noel AR, Bowker KE. 2009. Bacterial strain-to-strain variation in pharmacodynamic index magnitude, a hitherto unconsidered factor in establishing antibiotic clinical breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5181–5184. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00118-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.