Abstract

Infection with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) has been shown to cause significant illness among hospitalized patients. Given the paucity of treatment options, there is a critical need to stop the spread of CPE. However, screening for the presence of CPE in laboratory settings has been challenging. In order to assess the effectiveness of current CPE detection guidelines, we analyzed the meropenem MIC distribution for a large set of clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates. A total of 1,022 isolates submitted to the Public Health Ontario Laboratories (PHOL) from January 2011 to March 2014 were examined. Only isolates displaying a meropenem or ertapenem MIC of ≥0.25 or ≥1 μg/ml, respectively, were included. Carbapenemase-positive isolates were identified by multiplex PCR. We identified 189 isolates positive for carbapenemases, which primarily comprised NDM, KPC, and OXA-48-like carbapenemases, and these isolates were largely Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter spp. Interestingly, 14 to 20% of these isolates displayed meropenem MICs within the susceptible range on the basis of CLSI and EUCAST breakpoint interpretive criteria. While the majority of meropenem-susceptible CPE isolates were observed to be E. coli, meropenem susceptibility was not exclusive to any one species/genus or carbapenemase type. Application of CLSI screening recommendations captured only 86% of carbapenemase-producing isolates, whereas application of EUCAST recommendations detected 98.4% of CPE isolates. In a region with a low carbapenemase prevalence, meropenem-based screening approaches require a cutoff MIC near the epidemiological wild-type threshold in order to achieve nearly optimal CPE identification.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) has increased significantly in recent years, and CPE isolates are now endemic in many countries (1). Importantly, the options available for the treatment of infections caused by CPE are limited (2), and infection with CPE has been associated with substantial morbidity and with mortality rates of up to 50% (3–5). As a result, the need to curtail the dissemination of CPE is critical.

Stringent measures to control the transmission of CPE have been recommended by prominent organizations (6). However, the detection of CPE and confirmation of carbapenemase production have proven challenging due to the lack of sensitive and specific screening tests and of a consensus among the existing recommendations put forth by expert advisory groups (7–10). For example, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) proposes screening of isolates displaying an ertapenem or meropenem MIC of ≥2 μg/ml for carbapenemase production (7). The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) recommends a screening cutoff MIC of ≥0.25 μg/ml for both ertapenem and meropenem (10). The discrepancies between the screening guidelines described above are due, at least in part, to the limited availability of carbapenem MIC distribution data for different CPE species.

Previous reports indicate that the use of meropenem provides the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for the detection of carbapenemase activity (10–12), whereas ertapenem has high sensitivity but lacks specificity, as does imipenem (7, 10–14). In light of this and in an effort to better inform carbapenemase screening practices in Enterobacteriaceae, we investigated the meropenem MIC distribution profile of a large set of isolates with reduced susceptibility to carbapenems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical isolates.

The data set comprised clinical enterobacterial isolates (∼75%) and screening enterobacterial isolates (∼25%) submitted to the Public Health Ontario Laboratories (PHOL) from January 2011 to March 2014 for confirmation of carbapenemase-producing isolates. Isolates were submitted if they exhibited a meropenem or ertapenem MIC of ≥0.25 or ≥1 μg/ml, respectively (on the basis of provincial recommendations), as initially determined by the submitting laboratory. The meropenem MIC breakpoint was adopted from the EUCAST screening criteria. On the other hand, the 2014 CLSI nonsusceptible breakpoint was adopted for ertapenem, as ertapenem provides decreased specificity, albeit a higher sensitivity, at the EUCAST cutoff point. Meropenem and ertapenem MICs were redetermined at PHOL using the agar dilution method. All isolates that met the selection criteria were tested for carbapenemase activity and carbapenemase gene carriage (see below). All efforts were made to exclude replicate specimens in order to ensure that the final data set was comprised of unique isolates. Specifically, only one isolate/species/carbapenemase type was included in instances where replicate isolates from the same patient were submitted to PHOL. These criteria were influenced by standard practices for antibiogram preparation, and an arbitrary exclusion period of 6 months was selected. The isolates included in the final data set (n = 1,022) were comprised of bacterial species from 10 genera: Enterobacter (n = 480), Escherichia (n = 259), Klebsiella (n = 210), Serratia (n = 25), Citrobacter (n = 23), Morganella (n = 11), Pantoea (n = 5), Proteus (n = 5), Providencia (n = 3), and Hafnia (n = 1).

Molecular detection of carbapenemase genes.

For samples collected prior to July 2013, an endpoint multiplex PCR was used to identify carbapenemase gene carriage (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (15, 16). For samples collected in July 2013 and later, a real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR)-based approach was used. For RT-PCR, a Qiagen QuantiTect probe PCR kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Three separate RT-PCRs were run for each isolate to evaluate the isolate for the presence of the following genetic targets: 16S rRNA (extraction control), blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48-like, blaGES, blaVIM, and blaIMP (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The primers and probes were used at final concentrations of 0.5 and 0.125 μM, respectively. Thermal cycler conditions were as follows: enzyme activation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. A result was considered positive if the threshold cycle (CT) value was detected between cycles 10 and 30. The presence of carbapenemase activity was confirmed in parallel with molecular detection using a KPC/MBL confirmation kit (Rosco Diagnostica). All samples with discrepant results between PCR and the phenotypic test were further analyzed by the Carba NP test (17).

RESULTS

Of the 1,022 isolates tested, 188 (18.4%) were carbapenemase positive, on the basis of the results of genotypic and phenotypic analysis (see Table S2 in the supplemental material; data not shown): 90 were positive for the NDM carbapenemases (8.8% of the total isolates), 63 (6.2%) were positive for the KPC carbapenemases, 30 (2.9%) were positive for the OXA-48-like carbapenemases, 4 (0.4%) were positive for the VIM carbapenemases, and 1 (<0.1%) was positive for the IMP carbapenemase. One isolate was positive for two carbapenemase genes (NDM and OXA-48). Eight additional isolates were confirmed to be carbapenemase producers by the Carba NP test: 6 Serratia marcescens isolates were positive for blaSME, and 2 Enterobacter cloacae isolates were positive for blaNMC-A/IMI. These isolates were excluded from subsequent analyses, as their carbapenemases are chromosomally encoded and are not transmitted across species.

Meropenem MIC profile of carbapenemase-positive isolates.

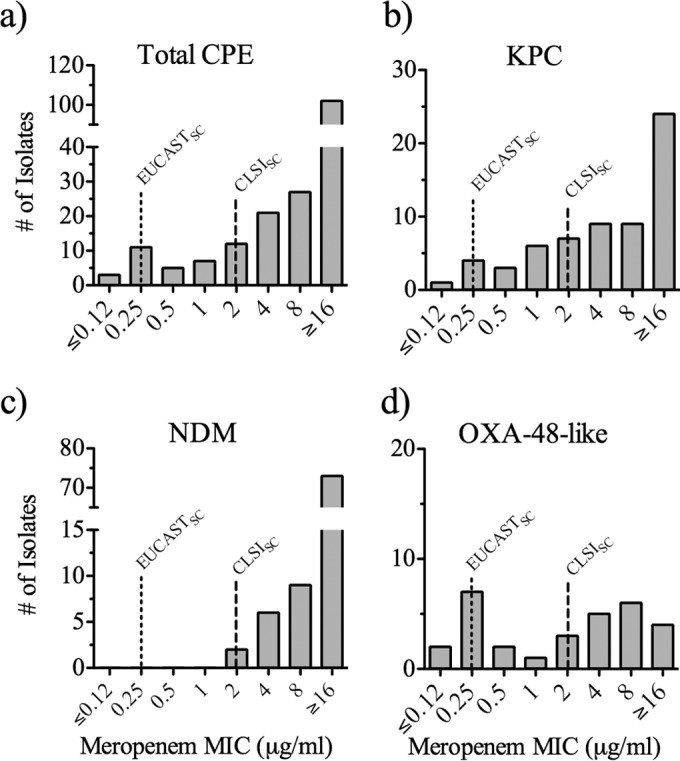

Overall, ∼70% (129/188) of the CPE isolates detected exhibited a meropenem MIC of ≥8 μg/ml (Fig. 1a; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Notably, on the basis of the CLSI (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml) and EUCAST (MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml) clinical breakpoints, 14% (26/188) and 20% (38/188) of CPE isolates, respectively, were considered susceptible to meropenem (Fig. 1a). On the basis of the meropenem screening breakpoint provided by CLSI (≥2 μg/ml), 86.2% (162/188) of the CPE isolates would have been detected (Fig. 1a). In contrast, application of the EUCAST screening breakpoint for meropenem (≥0.25 μg/ml) would have resulted in the detection of 98.4% (185 out of 188) of the CPE isolates in this data set (Fig. 1a).

FIG 1.

Meropenem MIC profile of CPE isolates. (a to d) MIC profiles of all CPE isolates (a) and isolates producing KPC (b), NDM (c), and OXA-48-like (d) carbapenemases, as detected by PCR. Lines with long and short dashes, CLSI and EUCAST screening breakpoints (CLSISC and EUCASTSC), respectively (refer to references 8 and 11, respectively).

The MIC profiles for the CPE isolates were further analyzed to examine whether the distribution of MICs varied among carbapenemase types and/or among bacterial genera. The data showed that approximately 25% (14/63 isolates) of KPC-producing isolates displayed a meropenem MIC of ≤1 μg/ml and thus would have been missed on the basis of the CLSI screening breakpoint (Fig. 1b). None of the NDM-positive isolates collected had meropenem MICs lower than 2 μg/ml (Fig. 1c). In contrast to the NDM-producing CPE isolates, the MICs for the OXA-48-like producing isolates were relatively distributed across the meropenem MIC range, with 40% of the isolates (12/30) displaying a meropenem MIC of ≤1 μg/ml (Fig. 1d). Meropenem MIC values for VIM-positive isolates (≥8 μg/ml; all isolates were of the genus Enterobacter) and an IMP-positive isolate of the genus Proteus (4 μg/ml) were generally observed to be at the higher range of the concentrations tested (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

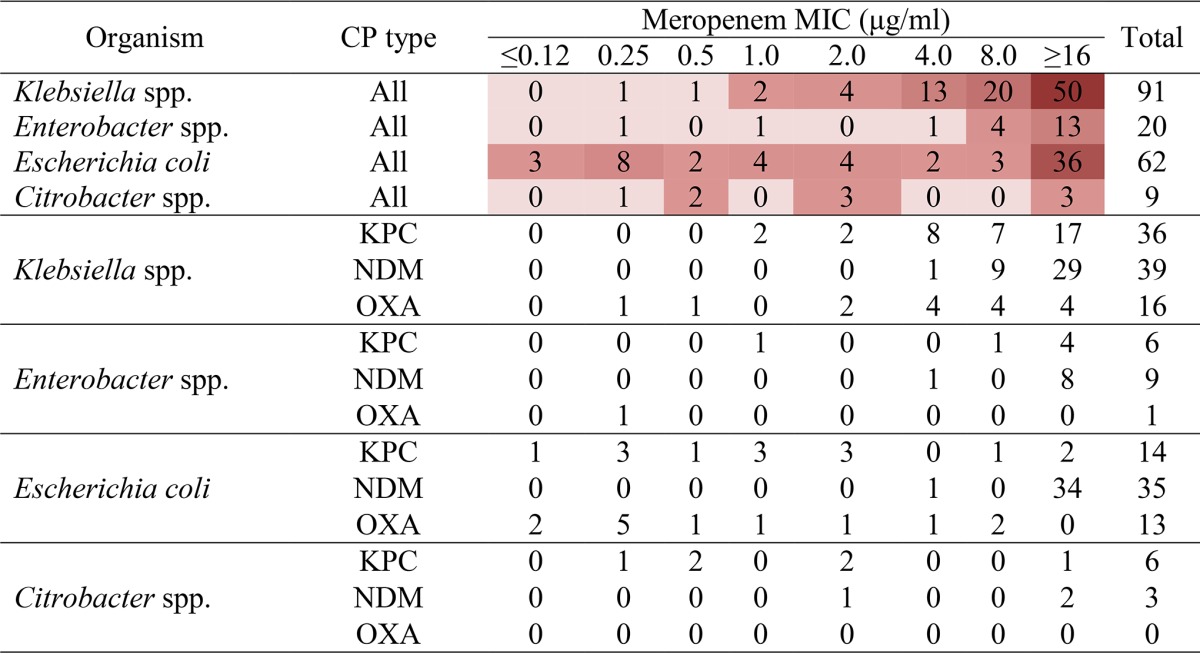

Analysis of the meropenem MIC profile among distinct bacterial genera revealed that most carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella (84/92) and Enterobacter (18/20) isolates displayed MIC values of >2 μg/ml (Table 1). In contrast, Escherichia and Citrobacter carbapenemase producers exhibited meropenem MICs relatively dispersed across the MIC range tested (Table 1). Examination of other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae included in this data set was not performed due to the small sample size (4 Morganella isolates, all of which were NDM producers with meropenem MICs of 2 to 4 μg/ml, and 1 Proteus isolate that produced IMP and that had a meropenem MIC of 4 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Meropenem MIC profile of predominant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolatesa

The values shown correspond to the number of carbapenemase-producing isolates (all types or individual types) of select organisms for which the MIC was as indicated; the intensity of the red color corresponds to the number of isolates. Carbapenemase status is based on PCR analysis. CP, carbapenemase.

The meropenem MIC data were further substratified to examine if any differences could be observed among different genera for a given carbapenemase, limiting the investigation to the genera with the highest number of isolates producing carbapenemases and the carbapenemases produced by the highest number of isolates. On the basis of this analysis, carbapenemase-positive Klebsiella species producing all prominent carbapenemases examined (i.e., the KPC, NDM, and OXA-48-like carbapenemases) frequently demonstrated moderate-to-high MICs (>2 μg/ml) (Table 1). Likewise, the NDM-producing E. coli isolates also exhibited relatively high MIC values (>4 μg/ml). On the other hand, the MICs for KPC-producing E. coli isolates were distributed across the MIC range tested (≤0.12 to ≥16 μg/ml), and those for OXA-48-producing E. coli isolates appeared at the lower end of the range (9 out of 13 isolates had a meropenem MIC of ≤1 μg/ml; Table 1). Similar to the findings for the Klebsiella isolates, KPC- and NDM-producing Enterobacter species demonstrated MIC values in the higher range of values tested (>4 μg/ml). Much like the findings for the E. coli isolates, KPC-producing Citrobacter isolates showed a broad meropenem MIC range (0.25 to ≥16 μg/ml; Table 1). No meaningful observations for OXA-48-like carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter species (n = 1) and NDM- or OXA-48-like carbapenemase-producing Citrobacter species (n = 3 and 0, respectively) could be made, as there were only a few such isolates in the data set (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The increasing prevalence of CPE around the world poses a significant threat to public health, as infections caused by CPE result in higher rates of morbidity and mortality. The accurate detection and the control of these organisms have become top priorities. Several studies have suggested that application of the CLSI susceptibility breakpoints affords excellent CPE detection (12, 13, 18–20). However, 14% of all CPE isolates identified in our data set would have been missed by the use of the current CLSI clinical and screening breakpoints. Interestingly, even though the EUCAST clinical recommendations classified 20% of carbapenemase-producing isolates as meropenem susceptible, application of the EUCAST screening recommendations detected the majority (>98%) of CPE isolates. There are a number of reasons that could account for the seeming discordance between the findings presented here and those presented in previous reports, including the limited sample size of CPE isolates examined, the use of CPE isolates collected at a time when laboratories employed higher screening MICs (i.e., prior to 2010), and the examination of single types of carbapenemases and/or bacterial species in the previous studies. Regardless, it is important to recognize that there are many factors that are likely to influence CPE detection in the clinical laboratory. Among the most important of the nontechnical factors are the type and endemicity of carbapenemases in a given geographical region at a given time. Indeed, adoption of CLSI guidelines in regions where carbapenem resistance is largely mediated by carbapenemases produced by isolates exhibiting moderate to high MICs (e.g., NDM-carrying isolates, KPC-producing Klebsiella isolates) would likely result in detection rates higher than those in areas where CPE isolates exhibiting low MICs exist (e.g., E. coli carbapenemase producers, OXA-48-like carbapenemase producers). In this study, there was also a considerable difference in the meropenem MIC distribution among CPE organisms, with 25% of KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates and 40% of OXA-48-like-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates displaying MICs below the CLSI screening breakpoint (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml). Therefore, it may be that no single guideline will provide universally optimal screening strategies (i.e., strategies that result in maximum detection with minimum cost and effort).

That 14% of CPE isolates may go undetected on the basis of current CLSI recommendations, we think, represents a significant pool of isolates that could further promote CPE dissemination. It is plausible that the transfer of plasmids harboring carbapenemase genes from a meropenem-susceptible isolate into an organism that may possess complementary antibiotic resistance determinants (e.g., the presence of other extended-spectrum β-lactamases, porin loss) may result in the emergence of a CPE isolate with elevated carbapenem MICs (21–23). Therefore, it would be important to detect the presence of carbapenemase genes even in those isolates deemed susceptible to carbapenems. Our findings suggest that lowering of the current meropenem screening breakpoints would considerably improve CPE detection.

Both CLSI and EUCAST recommend reporting of carbapenem susceptibility testing results on the basis of interpretive criteria irrespective of an isolate's carbapenemase status. The utility of carbapenems for the treatment of infections caused by CPE isolates displaying reduced susceptibility remains an issue of debate (3, 24–28). Thus far, the evidence is mixed, with some studies reporting an increased likelihood of achieving clinical success with carbapenem treatment when carbapenem MICs are below a particular threshold (e.g., 4 μg/ml) (3), while others have not observed such associations (27, 28). Until the issue can be clarified, it seems more prudent for clinical laboratories to detect and report the carbapenemase status of all isolates displaying reduced carbapenem susceptibility not only to prevent the transmission of carbapenemase genes but also to inform treatment strategies.

In summary, we show that approximately 14% of the CPE isolates in the data set used in this study would qualify as meropenem susceptible according to current CLSI criteria and, thus, would not be screened for the presence of carbapenemases. Given that meropenem is now a favored agent for screening for CPE, our findings indicate that meropenem-based CPE screening practices should employ a screening breakpoint of >0.12 μg/ml (i.e., the EUCAST epidemiological cutoff value) in order to maximize CPE detection. Future epidemiological studies should employ even lower MIC cutoffs in order to better understand the full range of carbapenem MICs displayed by CPE isolates. Importantly, failure to identify carbapenemase-carrying Enterobacteriaceae will drive further CPE dissemination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical help of the Reference Susceptibility Testing group at PHOL for its contribution to this study.

None of the authors has a conflict of interest.

We have no funding sources to declare.

Funding Statement

No funding was sought to perform this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02304-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel G, Bonomo RA. 2013. “Stormy waters ahead”: global emergence of carbapenemases. Front Microbiol 4:48. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Duin D, Kaye KS, Neuner EA, Bonomo RA. 2013. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 75:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daikos GL, Petrikkos P, Psichogiou M, Kosmidis C, Vryonis E, Skoutelis A, Georgousi K, Tzouvelekis LS, Tassios PT, Bamia C, Petrikkos G. 2009. Prospective observational study of the impact of VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase on the outcome of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1868–1873. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00782-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasink LB, Edelstein PH, Lautenbach E, Synnestvedt M, Fishman NO. 2009. Risk factors and clinical impact of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 30:1180–1185. doi: 10.1086/648451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel G, Huprikar S, Factor SH, Jenkins SG, Calfee DP. 2008. Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29:1099–1106. doi: 10.1086/592412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. CRE toolkit-guidance for control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/cre-toolkit/index. Accessed 2 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CLSI. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 24th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S24. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen Stuart J, Leverstein-Van Hall MA, Dutch Working Party on the Detection of Highly Resistant Microorganisms. 2010. Guideline for phenotypic screening and confirmation of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 36:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leclercq R, Canton R, Brown DF, Giske CG, Heisig P, MacGowan AP, Mouton JW, Nordmann P, Rodloff AC, Rossolini GM, Soussy CJ, Steinbakk M, Winstanley TG, Kahlmeter G. 2013. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:141–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giske CG, Martinez-Martinez L, Canton R, Stefani S, Skov R, Glupczynski Y, Nordmann PN, Wootton M, Miriagou V, Simonsen GS, Zemlickova H, Cohen-Stuart J, Gniadkowski M. 2013. EUCAST guidelines for detection of resistance mechanisms and specific resistances of clinical and/or epidemiological importance. http://www.eucast.org/resistance_mechanisms/.

- 11.Nordmann P, Gniadkowski M, Giske CG, Poirel L, Woodford N, Miriagou V, European Network on Carbapenemases. 2012. Identification and screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vading M, Samuelsen O, Haldorsen B, Sundsfjord AS, Giske CG. 2011. Comparison of disk diffusion, Etest and VITEK2 for detection of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with the EUCAST and CLSI breakpoint systems. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:668–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson KF, Lonsway DR, Rasheed JK, Biddle J, Jensen B, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Thompson A, Stocker S, Limbago B, Patel JB. 2007. Evaluation of methods to identify the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 45:2723–2725. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2009. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:659–667. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. 2010. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:490–495. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tijet N, Alexander DC, Richardson D, Lastovetska O, Low DE, Patel SN, Melano RG. 2011. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 17:306–307. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Rapid identification of carbapenemase types in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. by using a biochemical test. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6437–6440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01395-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endimiani A, Perez F, Bajaksouzian S, Windau AR, Good CE, Choudhary Y, Hujer AM, Bethel CR, Bonomo RA, Jacobs MR. 2010. Evaluation of updated interpretative criteria for categorizing Klebsiella pneumoniae with reduced carbapenem susceptibility. J Clin Microbiol 48:4417–4425. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02458-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulik CC, Fauntleroy KA, Jenkins SG, Abuali M, LaBombardi VJ, Nicolau DP, Kuti JL. 2010. Comparison of meropenem MICs and susceptibilities for carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates by various testing methods. J Clin Microbiol 48:2402–2406. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00267-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasteran F, Mendez T, Guerriero L, Rapoport M, Corso A. 2009. Sensitive screening tests for suspected class A carbapenemase production in species of Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 47:1631–1639. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00130-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arana DM, Saez D, Garcia-Hierro P, Bautista V, Fernandez-Romero S, Angel de la Cal M, Alos JI, Oteo J. 2015. Concurrent interspecies and clonal dissemination of OXA-48 carbapenemase. Clin Microbiol Infect 21:148.e1–148.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgia S, Lastovetska O, Richardson D, Eshaghi A, Xiong J, Chung C, Baqi M, McGeer A, Ricci G, Sawicki R, Pantelidis R, Low DE, Patel SN, Melano RG. 2012. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing blaNDM-1, Ontario, Canada. Clin Infect Dis 55:e109–e117. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tijet N, Richardson D, MacMullin G, Patel SN, Melano RG. 2015. Characterization of multiple NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the same patient. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3648–3651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04862-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuzon G, Ouanich J, Gondret R, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2011. Outbreak of OXA-48-positive carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2420–2423. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01452-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falagas ME, Lourida P, Poulikakos P, Rafailidis PI, Tansarli GS. 2014. Antibiotic treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: systematic evaluation of the available evidence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:654–663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01222-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livermore DM, Andrews JM, Hawkey PM, Ho PL, Keness Y, Doi Y, Paterson D, Woodford N. 2012. Are susceptibility tests enough, or should laboratories still seek ESBLs and carbapenemases directly? J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1569–1577. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souli M, Kontopidou FV, Papadomichelakis E, Galani I, Armaganidis A, Giamarellou H. 2008. Clinical experience of serious infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase in a Greek university hospital. Clin Infect Dis 46:847–854. doi: 10.1086/528719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisenberg SA, Morgan DJ, Espinal-Witter R, Larone DH. 2009. Clinical outcomes of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae after treatment with imipenem or meropenem. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 64:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.