Abstract

Swarming represents a special case of bacterial behavior where motile bacteria migrate rapidly and collectively on surfaces. Swarming and swimming motility of bacteria has been studied well for rigid, self-propelled rods. In this study we report a strain of Vibrio alginolyticus, a species that exhibits similar collective motility but a fundamentally different cell morphology with highly flexible snake-like swarming cells. Investigating swarming dynamics requires high-resolution imaging of single cells with coverage over a large area: thousands of square microns. Researchers previously have employed various methods of motion analysis but largely for rod-like bacteria. We employ temporal variance analysis of a short time-lapse microscopic image series to capture the motion dynamics of swarming Vibrio alginolyticus at cellular resolution over hundreds of microns. Temporal variance is a simple and broadly applicable method for analyzing bacterial swarming behavior in two and three dimensions with both high-resolution and wide-spatial coverage. This study provides detailed insights into the swarming architecture and dynamics of Vibrio alginolyticus isolate B522 on carrageenan agar that may lay the foundation for swarming studies of snake-like, nonrod-shaped motile cell types.

Introduction

Swarming, the shorthand description for the coordinated rapid migration of bacterial cells across surfaces, is an important but poorly understood aspect of bacterial multicellular behavior. Investigations of swarming both reveal basic mechanisms and functions of this developmental stage and provide insights of biomedical relevance as swarming has been associated with virulence for pathogens such as Proteus mirabilis (1, 2), Salmonella typhimurium (3), and Clostridium septicum (4). Swarming cells can also exhibit elevated antibiotic resistance compared with nonmotile populations (5, 6). Despite its basic and applied significance, swarming remains a poorly understood phenomenon, and research on swarm behavior at the population scale has largely focused on a small number of Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Paenibacillus dendritiformis strains (7, 8, 9, 10). These studies only explore the dynamics of relatively stiff, rod-shaped bacteria whose motion can be quantified by vector motion analysis. Bacteria such as V. alginolyticus, however, exhibit a very different morphology in which swarming cells are highly elongated and flexible, and move in a snake-like fashion. The resulting motion patterns of a swarming population of V. alginolyticus are significantly more complex and require completely different tools for their investigation.

Swarming of V. alginolyticus

Both V. alginolyticus and its close relative V. parahaemolyticus use a single polar flagellum for swimming motility in liquid medium, but on solid surfaces they differentiate into elongated swarmer cells with multiple lateral flagella (11). Both species are among the most frequently encountered marine bacteria, are known to cause diseases in vertebrate and invertebrate marine animals, and are emerging human pathogens especially in food poisoning and wound infections (12, 13). Although our understanding of the genetic basis of swarming in V. parahaemolyticus has made considerable progress (14, 15), swarming dynamics on population-level behavior have not been studied in detail in either species. In a recent study we isolated two strains, Shewanella algae B516 and V. alginolyticus B522, from a sample of red seaweed. Mimicking the natural seaweed substrate by the use of carrageenan as agar substitute, V. alginolyticus exhibited vigorous swarming behavior, which was antagonized by the S. algae strain. The inhibition of swarming was triggered by a small molecule produced by S. algae that we identified as a chimeric siderophore, which we named avaroferrin. We demonstrated that S. algae escapes iron piracy of V. alginolyticus by producing avaroferrin and thereby inhibits swarming (16). Our V. alginolyticus strain is thus a very interesting model for the ecological interaction of microorganisms and the modulation of swarming behavior. A crucial difference of swarming in V. alginolyticus and most other swarming species is its unusual snake-like morphology as opposed to stiff rod-like cells and peritrichous flagellation in contrast with polar flagellation of many other species. To study the interaction at the cellular level we developed a method for high-resolution imaging and analysis of time-lapse images that we report in this study together with the first investigation into the complex swarming behavior of V. alginolyticus. To our knowledge, this study represents the first in-depth investigation into the architecture and large-scale dynamics of swarming for highly flexible, nonrod-shaped motile cell type with snake-like swarming behavior.

Dynamics of bacterial swarming

Although numerous studies have investigated bacterial swarming there has been little attention paid to the details of swarm architecture, correlating the dynamics of bacterial swarming activity on the microscopic scale over the range of an entire colony. A number of studies focused on distinct biochemical, molecular, or morphological aspects of swarming such as the regulation of swarming behavior (17, 18), the number of flagella per cell, and the secretion of bacterially produced small molecules to reduce surface tension (19, 20). The complex motion patterns of swarming cells have been characterized well for rigid and rod-like swarmer cells (21, 22). For example, magnesium oxide (MgO) smoke particles have been used to track and study the surface motion of swarming bacteria (23, 24) and tracer beads allowed to analyze flow patterns (25); cell tracking has been applied to quantify cell velocities, flagellar dynamics, propulsion angles of individual cells (8, 26, 27), and fluctuations in cluster dynamics of swarms (7, 28); and image velocimetry has been used to measure vorticity fields and whirl correlations (29). Recently, tracking trajectories of individual cells of Bacillus subtilis and Serratia marcescens concluded that swarming bacteria migrate by Lévy walks (30).

However, all of these analyses and models of swarming focused on more or less stiff, rod-shaped cell types. In contrast, V. alginolyticus exhibits a snake-like swarming behavior that we report for the first time, to our knowledge, in greater detail. Previously very few studies have addressed swarming of nonrod-like swarming bacteria and none of them has addressed the swarm architecture of an entire swarming colony (31, 32). Correlating microscopic cell motility over a broad spatial array requires detection at the individual cell level ranging from large monolayers to more complex situations such as those presented by multilayered swarms.

To this aim, we have developed a simple, broadly applicable method based on temporal variance analysis for motion quantification of bacterial swarming behavior from microscopic time-lapse image series to give an integrated measure of the motility and microscopic population behavior. We illustrate the convenience and versatility of this method to obtain in-depth insights into cell motility within a bacterial swarm on an ecologically relevant model system for the snake-like swarming behavior of a colony of V. alginolyticus.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

All strains (Table S1 in the Supporting Material) were cultured in nutrient broth E (NBE, 1 g/L meat extract, 2 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L peptone, 5 g/L NaCl, pH 7.4) at 30°C with 250 rpm. Other media used for plates were HI swarming agar (25 g/L heart infusion broth, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ; 15 g/L NaCl, 15 g/L Difco agar) and lysogeny broth (LB; Difco LB broth, Becton Dickinson) plates with different percentage of Bacto or Difco agar.

Swarming plate assay

Carrageenan NBE plates for standard swarming assays of this study were prepared with 1.5% (w/v) carrageenan for gel preparation (predominantly containing κ-carrageenan, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; CAS: 9000-07-1; other carrageenan products are not equally suitable) in NBE (1 g/L meat extract, 2 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L peptone, 5 g/L NaCl, pH 7.4) using 25 mL per 100 mm plate. A 6 mm blank paper disc (BBL, Becton Dickinson) was placed in the center of a plate and inoculated with 5 μL overnight culture of the respective Vibrio strain in NBE medium and incubated at 30°C. All plate-based assays were carried out as independent triplicates on different plates.

Microscope data acquisition

Samples were cut out from carrageenan plates with a scalpel and carefully placed top-down on glass-bottom microwell dishes (MatTek (Ashland, MA), 35 mm petri dish, 14 mm microwell, No. 1.5 cover glass). It is important to not move the sample to avoid shear forces, which reduce the overall motility of the cells in the sample. Microwell dishes were mounted on a Prior ProScan II motorized stage and imaged at room temperature (Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA). All images were collected with a Nikon Ti motorized inverted microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 100× 1.4 NA objective lens and DIC optics. Images were acquired with a Hamamatsu Photonics (Hamamatsu City, Japan) ORCA-R2 cooled-CCD camera controlled with MetaMorph 7 software. For time-lapse experiments, images were collected every 500 ms using a 40 ms exposure time, for a duration of 15 s. Measurements were taken at least in triplicates from three independent plates, each.

Image analysis

Time-lapse series of typically 31 frames (15 s) were analyzed in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) using our analysis tools that can be requested free of charge from the authors.

Before all analyses, individual images were normalized to zero mean and unit variance, and Gaussian filtering was applied with a sigma equal to the Gaussian approximation of the microscope point-spread function. Then the per-pixel variance over time was calculated across the entire image series, producing a single temporal variance image V as follows:

| (1) |

where T is the number of time points, and I is the normalized, Gaussian-filtered image. When analyzing swarm front motion or the fraction of time with motion, a moving window was used to calculate a temporal variance image series:

| (2) |

where w is the window size, and t now ranges from 1 + w to T − w. To define regions in the moving-window variance analysis as moving or stationary, a threshold was determined from the 99th percentile of moving-window variance in a three-image series (w = 1) where no motion was present. To segment bacteria-free regions for identification of the swarming front, a local spatial standard deviation (SD) was calculated for each image, and the background spatial SD estimated by fitting the lower half of a Gaussian to the probability distribution function of the local spatial SD for the entire image stack as follows:

| (3) |

where A, μ, and σ define the Gaussian distribution we are fitting to estimate the background spatial SD in the local spatial SD images; A is amplitude, σ is standard deviation; μ is mean; xi is the image local spatial SD value with x1 equal to the minimum value found; P(xi) is the Gaussian kernel density estimate of the image local spatial SD probability distribution function at xi; and Iμ is the index i for which xi is closest to μ.

A mask identifying the cell-free region was then identified by thresholding the local spatial SD images at the 99th percentile of this estimated background, followed by morphological closure and hole-filling. The Euclidian distance transform of this mask was then used to quantify how the previously described motion parameters varied with distance from the swarming front. To measure the distance of advancement in the direction of the front, mask pixels bordering the front were found and the mean front direction across all images defined as follows:

| (4) |

where Yj,i is the ith pixel coordinate on the front border in the jth frame; M is the number of images in the series; and N is the number of pixels along a given front.

An area difference mask was then created by differencing the cell-free region masks in the first and last images (see Fig. 3 A, blue). The front advancement distance was then measured as the maximum width of this mask in the direction perpendicular the mean front direction determined in Eq. 4.

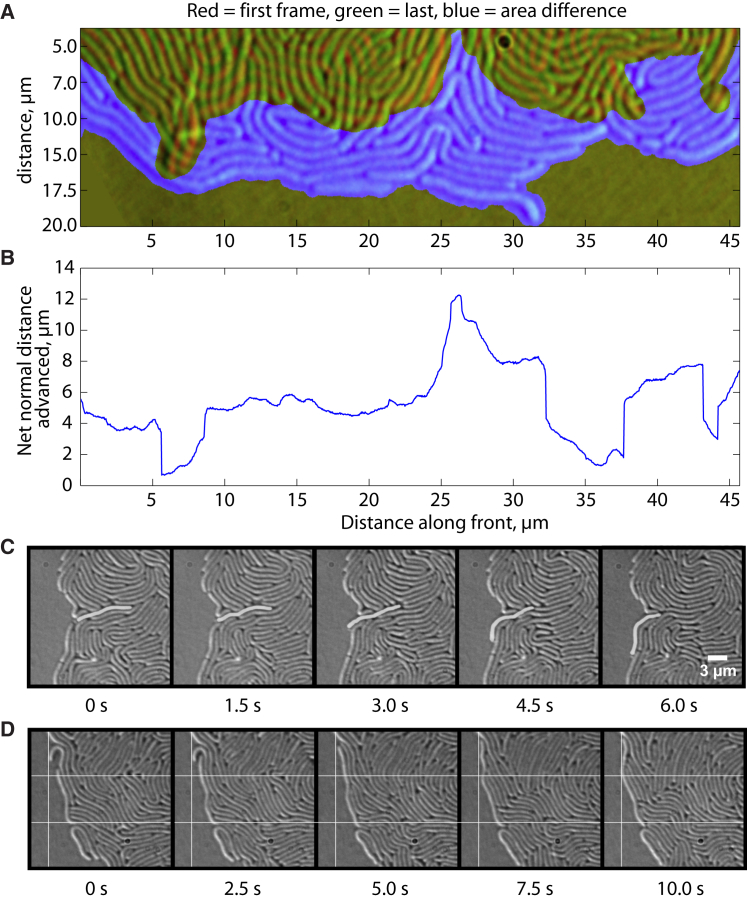

Figure 3.

Advancement of the swarming front: (A) overlay of the advancement of the front during 2.5 min and (B) the corresponding distance in μm advanced for different regions along the front. The (C) protrusion (cell highlighted) and (D) pushing modes of expansion of the natural swarming front over time and lateral sliding of cells at the front are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Negative staining transmission electron microscopy

Cells from the swarming front of V. alginolyticus B522 were scraped off and carefully resuspended in NBE medium, fixated with 4% formaldehyde, and adsorbed on glow discharged formvar/carbon-coated 100 mesh Cu/Hex grids. The grids were shortly washed in a drop of H2O and stained with 1% aqueous uranylacetate solution. Images were acquired with a JEOL USA (Peabody, MA) 1200EX transmission electron microscope equipped with an AMT Advanced Microscopy Techniques (Woburn, MA) 2k CCD camera.

Cell size measurements

The length of Vibrio cells were measured using Fiji with segmented lines with spline fit (Table S3).

Genome sequencing

Genomic DNA of V. alginolyticus B522 was extracted from 1.5 mL of an overnight culture in NBE using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA kit (Sigma Aldrich). The genome was sequenced by 100 bp single-end reads by next-generation sequencing using Illumina of the Harvard Biopolymers Facility.

Results

Mimicking the natural seaweed substrate of V. alginolyticus

Many marine microorganisms are associated with the surfaces of hosts such as seaweeds, and the highly diverse microbial communities on marine seaweeds have been described (33). Seaweeds are the starting material for the production of commercial agar, which typically is a purified mixture of sulfated and nonsulfated galactans, polysaccharides rich in galactose. We used carrageenan, a ubiquitous sulfated galactan of red seaweeds as substitute for agar with the aim of creating a more suitable mimic of the natural substrate for marine bacteria that we isolated from the red seaweed Chondrus crispus. This substrate proved to be exceptionally prolific at inducing swarming of Vibrio strains. One isolate, V. alginolyticus B522, exhibited rapid-swarming behavior and was used in this study. V. alginolyticus B522 swarmed rapidly as thin layers on LB or NBE 1.5% carrageenan plates after a ∼7 h lag phase with linear expansion of colony size of ∼5 mm/h and a mat to terrace morphology (Figs. 1 A and S2). The same strain did not swarm comparably on standard LB or NBE plates with 0.7% to 2.5% Bacto or Difco agar. After extended incubation times of several days on these substrates, dendrites and flares could be observed. Compared with commonly used HI swarming agar the cell layers were thinner and more homogeneous on carrageenan over a large macroscopic range. Carrageenan offered a superior alternative to other substrates as it reduced the complexity of swarming patterns and facilitated microscopy and image analysis.

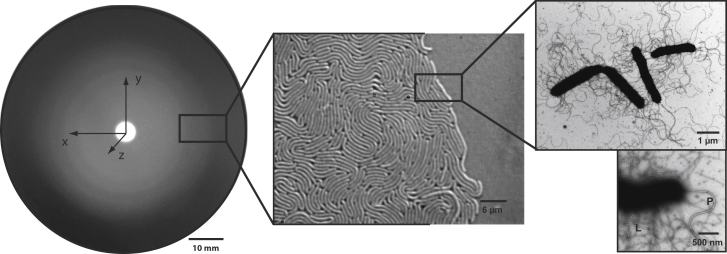

Figure 1.

Swarming of V. alginolyticus B522 on carrageenan with three magnifications: colony-swarming pattern on a plate with the coordinate system used in this study (10 mm), live cell imaging of the swarming front (6 μm), and TEM electron micrographs of cells with polar (P) and lateral (L) flagella (1 μm and 500 nm).

High-resolution phase-contrast microscopy of swarming cells of strain B522 on carrageenan showed densely packed elongated cells that were moving in horizontal layers (Fig. 1). Electron micrographs of negative-staining transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed peritrichously flagellated cells (cells covered with lateral flagella) from the swarming zone of plates, which are characteristic for swarming V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus (34). These strains rely on dual flagellar systems, whereby a single polar flagellum is the propulsion system for swimming activity, whereas lateral flagella are the driving force for swarming on solid media. The production of lateral flagella only is induced under high viscosity when the rotation of the polar flagellum is blocked (11, 35). The best results for swarming activity were obtained with a commercial κ-carrageenan mixture for gel preparations, which was used as standard method in this study, whereas ι-carrageenan resulted in a similar but more diffuse swarming morphology. Other Vibrio species tested, V. parahaemolyticus (three strains), V. vulnificus (two strains), and V. cholerae (one strain) did not swarm on carrageenan plates (Table S1).

Measuring motion by temporal variance

We applied temporal variance analysis of time-lapse image series from high-resolution phase-contrast microscopy of swarming cells as simple means to obtain a relative measure of motion. Temporal variance quantifies the degree of change in pixel brightness between images of a time-lapse series. A microscopic image is composed of pixels of different brightness ranging from white to black. In a stationary sample without motion, the brightness of every pixel position between consecutive images remains constant. In contrast, motion activity leads to changes in pixel brightness at a given position within a time-resolved image series. In other words, the more an object moves, the more pixels will change in brightness between two successive images. This method is very simple and easy to apply and has the advantage that it can be directly applied on microscopic image series with virtually no constraints on image type and quality and without the need to resolve or track individual cells. The method does not require the identification of individual cells, the presence of tracer particles as in particle image velocimetry (PIV), or the placing of strict requirements on the imaging parameters. In addition, in contrast with optical flow, temporal variance does not require motion measurements to be made over a defined length scale greater than the image resolution, allowing it to accurately represent locally variable and discontinuous motion and avoiding the tuning of analysis parameters. Although temporal variance cannot be directly translated into quantitative cell velocity, it gives a good measure of motion activity and is perfectly applicable to images of snake-like cells in multilayered swarms. We developed a simple method with three different analysis options that can be easily applied in a MATLAB environment (Fig. S1 A). In all analyses, individual images were mean and variance normalized to compensate for contrast and intensity changes attributable to illumination and focus variation. Gaussian filtering was applied to minimize the contribution of image noise to per-pixel temporal variance (Figs. S1, A–E). Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis gave an integrated measure of both the degree of motion and the areas and time during which motion occurred throughout the imaging period. To differentiate between the fraction of time spent moving and the associated speed, moving-window temporal variance analysis gave a measure of motion with increased time resolution. To identify discrete regions and time frames with significant motion, a minimum variance threshold was set by the maximum variance of control image series without bacterial motion. From this, heat maps showing the fraction of time during which significant motion was present in a given area were generated. Finally, the location of the swarming front was determined at each time point by identifying image regions devoid of bacteria. This allowed variation in both the moving-window temporal variance and the fraction of pixels with significant variance to be correlated with distance from the swarming front.

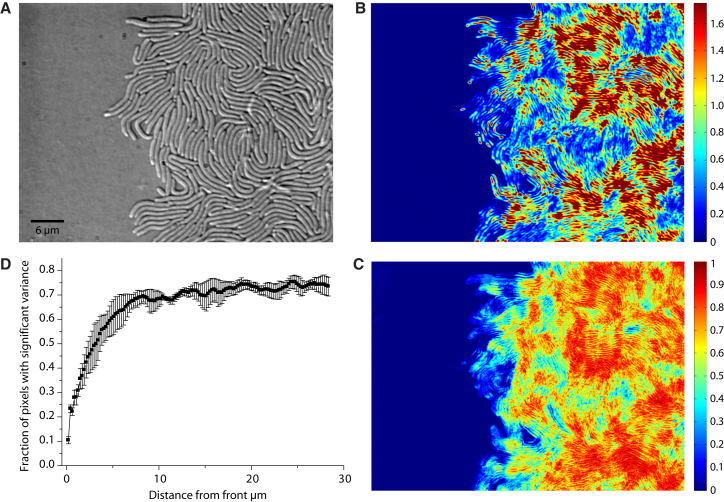

Motion at the swarming front

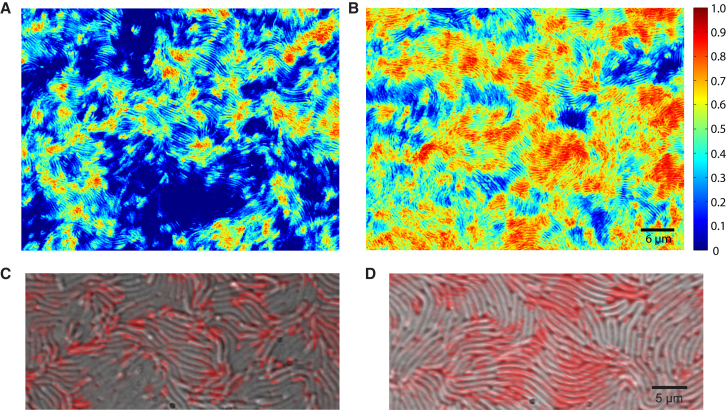

The swarming front of V. alginolyticus B522 consisted of a well-defined monolayer of cells (Fig. 2 A). Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis of the swarming front indicated correlation of cell movement in jets and swirls with clusters of high motion coexisting with patches of low-motion activity (Fig. 2 B). The areas distant from the front showed a high degree of motion whereas the cells directly adjacent to the front showed less activity. As this analysis would not differentiate between short pulses of fast motion and continuous slower motion, we quantified the fraction of time with significant variance. Although the cells far from the front showed a relatively continuous motion, motion at the front appeared rather as brief pulses of movement (Fig. 2 C). We thus used our third analysis method to plot the fraction of pixels with significant variance against the distance from the front, taking the advancement of the front itself into account. The results confirm that motion of cells becomes less frequent ∼8 μm away and further decreases near the front so that within ∼5 μm cells are more often stationary than moving. Individual cells do not leave the collective of swarming cells and their motion generally halts once they have reached the border with uncolonized carrageenan (Fig. 2 D). This effect may be attributable to the slowly diffusing surfactants, wetting of the unoccupied carrageenan, or small molecule factors that are required for swarming.

Figure 2.

Motion analysis of the swarming front. (A) Phase-contrast image of the swarming front is shown at the start of the time-lapse image series. (B) Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis indicates patches of different intense motion activity: high variance (red) and low variance (blue). (C) The fraction of time with significant variance analysis reveals decreasing motion toward the swarming front: large fraction of time with significant variance (red) and small fraction of time with significant variance (blue). (D) The fraction of pixels with significant variance is plotted against the distance from the front averaged from three independent replicates. To see this figure in color, go online.

Orientation of cells directly at the outer swarming front is largely perpendicular (tangential) to the direction of swarming and cells frequently slide tangentially along the front. The advancement of the front generally proceeds nonmonotonically with large fluctuations on the microscopic scale that even out over time (Figs. 3, A and B, and S3). These fluctuations are the result of protruding and retracting movements of cells and cell clusters (Fig. S3).

The swarming front advances into uncolonized areas by two distinct modes: 1) by the protrusion of highly motile cells from the inner part close to the front (Fig. 3 C) that may occasionally result in eruptions of smaller groups of cells, and 2) by the passive pushing of vertical cells of the outer front by the pressure generated in the active zones behind the front (Fig. 3 D).

We prepared a short movie showing the progression of the swarming front and motion of cells behind the front in time-lapse series over 2.5 min including an overlay of motion analysis from moving-window temporal variance analysis (Movie S1).

General motion profile in x- and z-dimensions

We next examined the large-scale pattern of the swarming behavior in relation to the distance from the swarming front. The front consisted of an extended monolayer, which stretched out usually around 1 mm beyond where additional layers started to be colonized (Fig. 4 A).

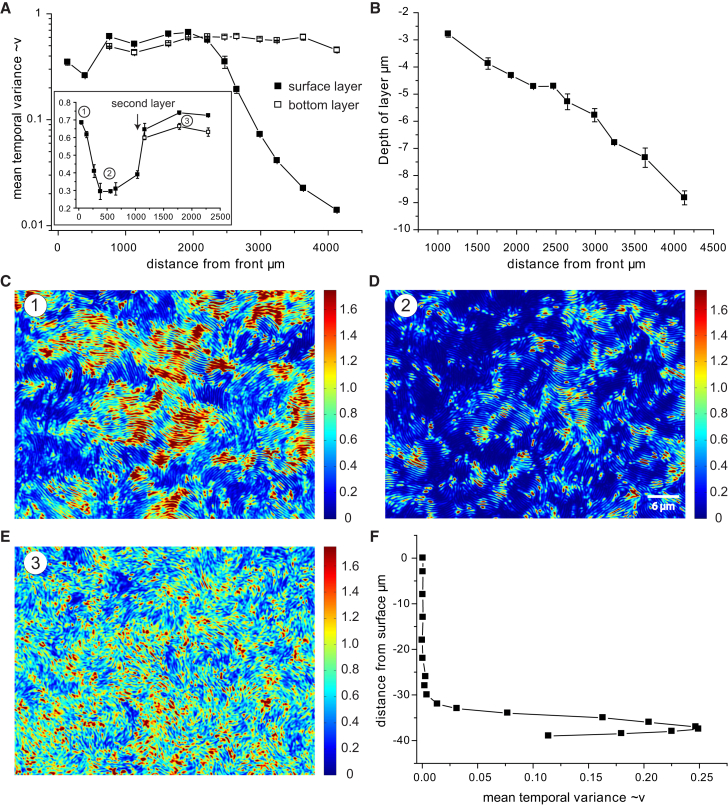

Figure 4.

Swarming in the x- and z-dimensions. (A) The mean temporal variance changes with the distance from the swarming front differently for surface and bottom layer. (B) Depth (thickness) of the cell layer is measured from the surface versus distance from the swarming front. Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis heat maps show different swarming phases: (C) close to the swarming front, (D) at ∼500 μm distance to the front, and (E) in the top layer at 2.3 mm distance to the front. In all images the spatial coverage by cells is 100%. (F) Only a thin layer at the bottom around 40 μm from the surface of the mature colony is motile (high temporal variance), whereas the surface is stationary. To see this figure in color, go online.

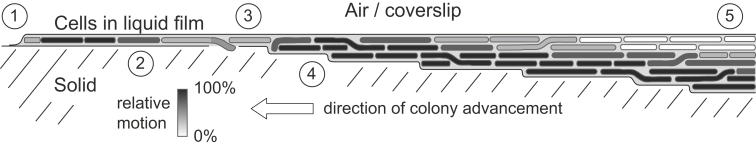

Temporal variance analysis in the surface monolayer revealed three phases (Figs. 4 A, inset, and 4, C–E): 1) a rapidly swarming monolayer close to the swarming front; 2) a sharp decrease in velocity of cell motion in the monolayer within the first hundred microns from the swarming front; and 3) a recovery to the initial speed when swarming cells began occupying additional layers underneath the original monolayer. Bacterial cells only exist in the liquid film between the air/glass and the solid substrate, which is too dense to be penetrated. We will refer to the layer at the interface to the air/glass as the surface (or upper) layer and to the layer at the barrier posed by the carrageenan as the bottom layer. After the swarming colony began occupying layers in the z-dimension, the depth (thickness) of the cell layer increased almost linearly with distance in direction of the bottom layer (Fig. 4 B).

Only the bottom layer is continuously motile

Once additional layers were established, the motion of cells at the bottom layer (bacteria-carrageenan interface) remained almost constant with distance from the front, whereas the surface layer started losing its motility usually ∼2–3 mm from the front (Fig. 4 A) when the layer reached a thickness of ∼5 μm and decreased more than one order of magnitude at ∼7 μm. We profiled the temporal variance over the distance of the focal plane from the surface in a mature multilayer swarming colony and consistently found that the mobile layer of cells was restricted to a zone of ∼7 μm thickness at the bottom layer (Fig. 4 F). The temporal variance and thus cell motility peaked directly at the interface to the solid medium and rapidly decreased in the direction of the surface. The upper layers adjacent to the air-cell interface remained stationary and the thickness of the nonmotile layer steadily increased with distance from the front whereas the thickness of the motile bottom layer remained constant.

Phase-contrast images confirmed that with increasing thickness of the layer the cells intrude more into the carrageenan. In a distance of ∼1 cm from the front the interface of cells to the carrageenan was no longer smooth as in the monolayer but contained wrinkles and islands of solid grains with dimensions of several microns, which were the result of heterogeneous abrasion of the surface (Fig. S4).

Movement out of the monolayer

We were interested in examining how bacteria leave the monolayer at the early recovery phase after initial decrease in motion activity (late phase 2, ∼1000 μm from the front) and start building up new layers under the surface. Microscopic examination together with fraction of time with significant variance analysis of this phase revealed that mainly short pulses of motion occurred (Fig. 5 A and Movie S2), whereas close to the front, continuous motion activity was observed (Fig. 5 B). Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis of late phase 2 overlaid with the phase-contrast image showed that movement of cells mainly involved “exploratory” behavior in the z-dimension characterized by motion active zones at the tips of elongated cells (Fig. 5 C) with short-time movements underneath the existing monolayer whereas motion within in the xy plane of the monolayer was mostly absent. In contrast, motion in phase 1 involves patches of movement of whole cells in the xy plane (Fig. 5 D). The short-term motion pulses illustrated in Fig. 5 A were thus mainly attributable to cells sliding forth and back in the z-dimension.

Figure 5.

(A) The fraction of time with significant variance analysis of cells at ∼1000 μm distance from the swarming front and, for comparison, (B) the fraction of time with significant variance analysis in phase 1, corresponding to Fig. 4C. (C) Overlay of whole-image-series temporal variance analysis (red) of cells in late phase 2 with phase-contrast images (gray) is shown. Movement in the z-dimension can be inferred from real-time microscopy and the overlapping of cells. Motion is restricted mainly to foci at the tips of cells, whereas motion of cells in phase 1 (D) is confined to the xy-dimension. To see this figure in color, go online.

V. alginolyticus as model for swarming

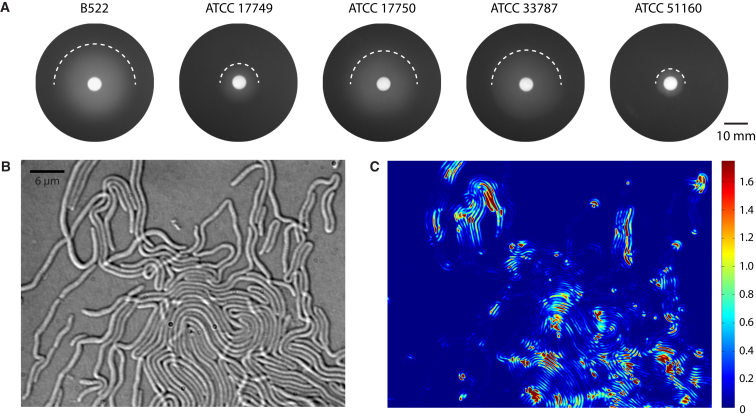

We investigated whether other strains of V. alginolyticus would also swarm on carrageenan and tested several standard strains of the ATCC collection. V. alginolyticus strains ATCC 17750 and ATCC 33787 showed a rapid swarming behavior similar to that of strain B522, which we designate as the fast swarmers (Fig. 6 A). In contrast, the type strain of V. alginolyticus ATCC 17749 and strain ATCC 51160 did not swarm readily (designated slow swarmers), and ATCC 51160 was the poorest swarming strain. Colonies of slow swarmers advanced much more slowly and in thicker layers than did fast swarmers (Fig. 6 A). Both fast- and slow-swarmer strains clustered in phylogenetic multilocus analysis using concatenated rpoD, rctB, and toxR gene sequences (Fig. S5).

Figure 6.

(A) Swarming morphology of different strains of V. alginolyticus on NBE carrageenan plates (scale bar, 10 mm), with the top half of the swarming edge highlighted by a dashed line. (B) Phase-contrast image of the swarming front of the slow-swarming strain V. alginolyticus ATCC 17749 highly elongated cells and a lack of a clearly defined front is shown at the start of the time-lapse image series. (C) Whole-image-series temporal variance analysis indicates only low-motion activity compared with fast swarmers. To see this figure in color, go online.

We compared the swarming behavior of the different strains by high-resolution phase-contrast microscopy and temporal variance analysis. The overall motion at the cellular level was highly reduced in all slow swarmers compared with fast-swarming strains (Figs. 2 B, 6 C, and S6). Statistical evaluation of cell sizes showed a strong correlation between average cell length and swarming activity (Figs. S6 and S7). The three fast-swarming strains were characterized by significantly shorter cells of a mean average length of 9–11 μm, whereas both slow swarmers had extremely elongated cells averaging 33–50 μm in length with some individual cells exceeding 100 μm in length (Table S3 and Fig. S7). Slow-swarming strains lacked a well-defined, densely packed swarming front and exhibited loosely connected patches of cells and loops of individual cells protruding into the unoccupied carrageenan, which were mostly stalled in motion (Figs. 6, B and C, and S6). Cells that were close to the swarming front typically were organized in large whirls blocking each other and frequently overlapping, which may contribute to reduced motion activity. We sequenced V. alginolyticus B522 so that in addition to the genome of the type strain, V. alginolyticus ATCC 17749, genomic sequence data for both fast- and slow-swarming types will be available to provide a set of genetically characterized strains for studying swarming behavior.

Discussion

Swarming represents the collective behavior of large numbers of bacterial cells. Characterizing complex swarm dynamics requires data and analytical tools that quantify the motions of individual cells and their neighbors over lengths that are orders of magnitude larger than the individual cells comprising the swarm. Our results establish two things: the utility of carrageenan agar as a swarming substrate for V. alginolyticus and, more importantly, the first detailed insights, to our knowledge, into the swarming architecture of highly flexible, snake-like swarmer cell over the range of an entire colony.

We discovered carrageenan is an especially suitable substrate for microscopic evaluation of V. alginolyticus swarming behavior as it promotes swarming in a thin-layer colony morphology that is simple to analyze. Swarming of V. alginolyticus on carrageenan is also rapid and robust, in contrast with descriptions in the literature of swarming on other substrates, where swarming usually required long incubation times (24–48 h), reached only short distances, and displayed flare/dendrite-like morphologies (36, 37). Additionally, carrageenan induced V. alginolyticus swarming with standard growth media that usually do not support swarming. All of these features allowed us to obtain high-resolution time-lapse image series of the swarming behavior that were suitable for analysis of bacterial swarming dynamics.

Unlike the relatively stiff, rod-shaped swarmer cells of Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Paenibacillus dendritiformis, cells of V. alginolyticus display almost snake-like behavior with extensive bending of their long cells during movement (7, 8, 29). Applying temporal variance analysis provided a simple means to qualitatively assess motion activity even when cells move in multiple entangled layers and when adjacent cells move discontinuous and in different directions. Although the method does not measure absolute velocities, the relative motion measure it provides gives a clear picture of dynamics within the swarm. Our analytical method is broadly applicable and is likely to provide a useful tool to study swarming behavior in additional species.

Our study is the first detailed report, to our knowledge, of microscopic swarming behavior of a nonrod-shaped, snake-like bacterial species over a broad spatial array of an entire swarming colony. Previous studies have largely focused on swarming pattern of a single monolayer of cells in a field of only several tens of micrometers. A very limited amount of work has so far been conducted on nonrod-shaped swarming bacteria and these studies have focused on the mechanism of interstitial vortex formation of Paenibacillus vortex and the dynamics of spiral coil formation of V. alginolyticus (31, 32). In addition to extensive colony-wide investigation of swarming in all three dimensions, our observations also were strikingly different from the previously reported nonrod-shaped swarms. On carrageenan agar our strain of V. alginolyticus swarmed as densely packed layers. Typically swarming colonies exhibit large density fluctuations that come along with dynamic cluster formation (7, 8). However, in our system there were no such fluctuations within the swarm and cells were constantly packed at maximum density. The dense packing in combination with highly flexible, snake-like cells has important consequences for steric and hydrodynamic effects that are essentially different from stiff self-propelled rods. The swarming motility is in this case entirely governed by the hydrodynamic regime of neighboring cells and orientations are coherent over a broad spatial range. Steric effects known from stiff rods resulting in variations in propulsion angles in relation to other cells and random nonaligned movements were here completely absent (8). In rod-shaped bacteria and swarms with lower cell packing density, individual cells are temporarily recruited into local multicellular rafts that move with aligned orientation and velocity vectors (19, 26). It has been proposed that interactions and bundling of flagella of aligned cells is important for the formation of multicellular rafts in other species (26, 38). As shown in our study, even with maximum packing density, cells clustered in local rafts with aligned motion activity. Thus, our V. alginolyticus strain swarming on carrageenan illustrates an extreme case of cell density with high correlation of cell orientations. Extensive bending of these highly elongated flexible cells also frequently led to discordant orientations of aligned clusters of cells. Our results indicate that a swarming colony is highly heterogeneous in all dimensions: swarming activity and behavior changes greatly from the center to the swarming front and also throughout the z-dimension. In general, temporal variance analysis of swarming V. alginolyticus revealed long-range coherence of bacterial motion that results in pattern formation with jets, swirls, and distinct areas with alternating high- and low-motion activities (Fig. 2, B and C). This self-organization of groups of cells is most likely a physical phenomenon generated by the hydrodynamic interactions of self-propelled cells with neighboring cells (9). Although the swarming of snake-like cells of V. alginolyticus exhibited many features known from swarms of stiff rod-shaped cells, models have so far mainly taken into account self-propelled rods and rod shape was implicated in inducing collective motion (39, 40). Our analysis, which showed that V. alginolyticus cells directly at the swarming front were largely stalled (Fig. 2 D), parallel earlier observations for E. coli and P. dendritiformis (8, 29). The sharp decrease in bacterial motion at the swarming front may thus be a universal property of swarms. It has been proposed that cells at the front pump fluid outward to wet the agar and thereby support swarm expansion (8) or spread on surfactant waves (41). The combination of surface wetting and surfactant diffusion along with reduced hydrodynamic interaction with neighboring cells compared with cells in the middle of the swarm that are completely surrounded on all sides by motile cells may all be reasons for the lower-motion activity at the front. We showed that the advancement of the swarming front proceeds discontinuously on the microscale and is mainly driven by protrusion of cells and outbursts of jets as well as pushing of cells from behind the front. In addition to the high-motion activity close to the front, we observe decreased motion within the monolayer that trails the front by several hundred micrometers. The reason for this effect remains elusive, but it may be associated with the depletion of nutrients in the carrageenan surface or accumulation of metabolic by-products. Although this observation is qualitatively similar to the decrease of motion in P. dendritiformis with distance from the front (29), V. alginolyticus exhibits a recovery of the initial motility that to our knowledge has not been previously reported in swarming bacteria. This recovery phase originates with the cells leaving the colony and starting to explore and occupy additional layers underneath the original surface monolayer. The layers linearly increase in depth, and we provide evidence that the additional layers in fact are created by abrasion of the surface of the carrageenan. The cells move in flat layers under the previous layers that may increase nutrient recovery from the carrageenan. Which factors trigger the behavioral change from two-dimensional swarming in a monolayer to three-dimensional swarming remain to be investigated. The motion activity was confined to a relatively thin band of ∼7 μm from the interface to the solid medium. The older layers above this band were stationary, which supports a hypothesis that searching for nutrients could be the reason for swarming of V. alginolyticus. We combined our data to generate a swarming dynamics cartoon for V. alginolyticus B522 in Fig. 7. The swarming colony is thereby not horizontally stratified in sharp layers but rather in a continuum with different extremes of motility. If this behavior occurs in the natural environment or is restricted to our model system in an artificial environment remains to be investigated.

Figure 7.

Model of a swarming colony: (1) swarming front, (2) phase of reduced motion, (3) motion increases in z-dimension, (4) new layers of highly motile cells form underneath the original layers, and (5) motion of cells on the surface layer sharply decreases with increasing thickness until static. Bacteria are able to freely move between the layers as indicated in the model.

To test the generality of our results beyond V. alginolyticus B522, we investigated additional strains. Although all of the strains swarmed in a qualitatively similar fashion, they separated into two groups with quantitatively different swarming activity. Fast-swarming strains such as B522 were characterized by comparably shorter cell sizes and a well-defined swarming front; whereas slow-swarming strains including the type strain of V. alginolyticus exhibited much longer cells, did not align into a well-defined front, and showed only low-motion activity on microscopic scale. It is likely that increased cell length results in physical limitations that limit rapid swarming and it is possible that domestication of strains may have selected against an extensive swarming phenotype. The genome sequence data of these strains should provide a basis for further investigations into the genetic bases of swarming, morphology, and behavior within and between swarming strains of V. alginolyticus. The analytical methods for characterizing swarming motility described in this article will aid in these tasks. Finally we have demonstrated that V. alginolyticus B522 with its flexible, snake-like cells swarms in a fashion fundamentally different from the commonly described swarms of stiff rod-shaped cells, although they both move collectively and form a complex colonies organized into distinct zones both horizontally and vertically.

Author Contributions

T.B. and J.C. designed the research. H.L.E. developed the image analysis tools. T.B. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.B., J.C., and H.L.E. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Waters and the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School for use of the high-resolution microscope. Image analysis and software tool development was performed at the Image and Data Analysis Core (IDAC) at Harvard Medical School. We are grateful to Louise Trakimas and the Harvard Medical School EM facility for help with transmission electron microscopy. We thank Michael Brenner for valuable discussions.

H.L.E. and the Image and Data Analysis Core were supported by the Harvard Medical School Tools and Technology Program. T.B. thanks Andreas Marx for the generous support at the University of Konstanz. This research was also supported by a Leopoldina Research Fellowship (LPDS 2009-45) of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (T.B.), funding by the Emmy Noether program of the DFG (T.B.), Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (T.B.), EU FP7 Marie Curie Zukunftskolleg Incoming Fellowship Program, University of Konstanz grant no. 291784 (T.B.), NIH GM086258 (J.C.), and NERCE-BEID through 5U54 AI057159 (J.C.).

Editor: Reka Albert

Footnotes

Seven figures, three tables, and two movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)00044-8.

Contributor Information

Thomas Böttcher, Email: thomas.boettcher@uni-konstanz.de.

Jon Clardy, Email: jon_clardy@hms.harvard.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Allison C., Lai H.C., Hughes C. Co-ordinate expression of virulence genes during swarm-cell differentiation and population migration of Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 1992;6:1583–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison C., Emödy L., Hughes C. The role of swarm cell differentiation and multicellular migration in the uropathogenicity of Proteus mirabilis. J. Infect. Dis. 1994;169:1155–1158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q., Frye J.G., Harshey R.M. Gene expression patterns during swarming in Salmonella typhimurium: genes specific to surface growth and putative new motility and pathogenicity genes. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macfarlane S., Hopkins M.J., Macfarlane G.T. Toxin synthesis and mucin breakdown are related to swarming phenomenon in Clostridium septicum. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1120–1126. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1120-1126.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler M.T., Wang Q., Harshey R.M. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3776–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910934107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai S., Tremblay J., Déziel E. Swarming motility: a multicellular behaviour conferring antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;11:126–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H.P., Be’er A., Swinney H.L. Collective motion and density fluctuations in bacterial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13626–13630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001651107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darnton N.C., Turner L., Berg H.C. Dynamics of bacterial swarming. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2082–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aranson I.S., Sokolov A., Goldstein R.E. Model for dynamical coherence in thin films of self-propelled microorganisms. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2007;75:040901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.040901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Be’er A., Strain S.K., Florin E.L. Periodic reversals in Paenibacillus dendritiformis swarming. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:2709–2717. doi: 10.1128/JB.00080-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarter L., Silverman M. Surface-induced swarmer cell differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Mol. Microbiol. 1990;4:1057–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelapati S., Nelapati K., Chinnam B.K. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: an emerging foodborne pathogen. Vet World. 2012;5:48–62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustapha S., Mustapha E.M., Nozha C. Vibrio alginolyticus: an emerging pathogen of foodborne diseases. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2013;2:302–309. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart B.J., McCarter L.L. Lateral flagellar gene system of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4508–4518. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4508-4518.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick J.E., Kearns D.B. Swarming motility and the control of master regulators of flagellar biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;83:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Böttcher T., Clardy J. A chimeric siderophore halts swarming Vibrio. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:3510–3513. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickzad A., Lépine F., Déziel E. Quorum sensing controls swarming motility of Burkholderia glumae through regulation of rhamnolipids. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Givskov M., Ostling J., Kjelleberg S. Two separate regulatory systems participate in control of swarming motility of Serratia liquefaciens MG1. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:742–745. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.742-745.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearns D.B. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:634–644. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniels R., Vanderleyden J., Michiels J. Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004;28:261–289. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benisty S., Ben-Jacob E., Be’er A. Antibiotic-induced anomalous statistics of collective bacterial swarming. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;114:018105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.018105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H.P., Be’er A., Swinney H.L. Swarming dynamics in bacterial colonies. EPL-Europhys. Lett. 2009;87:48011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Be’er A., Harshey R.M. Collective motion of surfactant-producing bacteria imparts superdiffusivity to their upper surface. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang R., Turner L., Berg H.C. The upper surface of an Escherichia coli swarm is stationary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:288–290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912804107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darnton N., Turner L., Berg H.C. Moving fluid with bacterial carpets. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1863–1870. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copeland M.F., Flickinger S.T., Weibel D.B. Studying the dynamics of flagella in multicellular communities of Escherichia coli by using biarsenical dyes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:1241–1250. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02153-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner L., Zhang R., Berg H.C. Visualization of flagella during bacterial swarming. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:3259–3267. doi: 10.1128/JB.00083-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X., Dong X., Zhang H.P. Scale-invariant correlations in dynamic bacterial clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:148101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.148101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Be’er A., Smith R.S., Swinney H.L. Paenibacillus dendritiformis bacterial colony growth depends on surfactant but not on bacterial motion. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:5758–5764. doi: 10.1128/JB.00660-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ariel G., Rabani A., Be’er A. Swarming bacteria migrate by Lévy walk. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8396. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallotton P. Size matters: filamentous bacteria drive interstitial vortex formation and colony expansion in Paenibacillus vortex. Cytometry Part A. 2013;83:1105–1112. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S.N., Lo W.C., Lo C.J. Dynamics of self-organized rotating spiral-coils in bacterial swarms. Soft Matter. 2014;10:760–766. doi: 10.1039/c3sm52120f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egan S., Harder T., Thomas T. The seaweed holobiont: understanding seaweed-bacteria interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013;37:462–476. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belas M.R., Colwell R.R. Scanning electron microscope observation of the swarming phenomenon of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 1982;150:956–959. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.956-959.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarter L.L. Dual flagellar systems enable motility under different circumstances. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;7:18–29. doi: 10.1159/000077866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulitzer S. The mechanism of swarming of Vibrio alginolyticus. Arch. Microbiol. 1975;104:67–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00447301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Boer W.E., Golten C., Scheffers W.A. Effects of some chemical factors on flagellation and swarming of Vibrio alginolyticus. A. Van Leeuw. 1975;41:385–403. doi: 10.1007/BF02565083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones B.V., Young R., Stickler D.J. Ultrastructure of Proteus mirabilis swarmer cell rafts and role of swarming in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:3941–3950. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3941-3950.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peruani F., Starruss J., Bär M. Collective motion and nonequilibrium cluster formation in colonies of gliding bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:098102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.098102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peruani F., Deutsch A., Bär M. Nonequilibrium clustering of self-propelled rods. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2006;74:030904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.030904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angelini T.E., Roper M., Brenner M.P. Bacillus subtilis spreads by surfing on waves of surfactant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18109–18113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.