Abstract

Endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) isolated from umbilical cord blood (CBECFCs) are highly proliferative and form blood vessels in vivo. The purpose of this investigation was to isolate and characterize a population of resident ECFCs from the chorionic villi of term human placenta and provide a comparative analysis of their proliferative and vasculogenic potential with CBECFCs. ECFCs were isolated from umbilical cord blood and chorionic villi from placentas obtained by caesarean deliveries. Placental ECFCs (PECFCs) expressed CD144, CD31, CD105, and KDR and were negative for CD45 and CD34, consistent with other ECFC phenotypes. PECFCs were capable of 28.6 ± 6.0 population doublings before reaching senescence (vs. 47.4 ± 3.2 for CBECFCs, p < 0.05, n = 4). In single cell assays, 46.5 ± 1.2% underwent at least one division (vs. 51.0 ± 1.8% of CBECFCs, p = 0.07, n = 6), and of those dividing PECFCs, 71.8 ± 0.9% gave rise to colonies of >500 cells (highly proliferative potential clones) over 14 days (vs. 69.4 ± 0.7% of CBECFCs, p = 0.07, n = 9). PECFCs formed 5.2 ± 0.8 vessels/mm2 in collagen/fibronectin plugs implanted into non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, whereas CBECFCs formed only 1.7 ± 1.0 vessels/mm2 (p < 0.05, n = 4). This study demonstrates that circulating CBECFCs and resident PECFCs are identical phenotypically and contain equivalent quantities of high proliferative potential clones. However, PECFCs formed significantly more blood vessels in vivo than CBECFCs, indicating that differences in vasculogenic potential between circulating and resident ECFCs exist.

Key words: Vascular endothelial cells, Endothelial progenitor cells, Placenta, Vasculogenesis, Pluripotent stem cells

INTRODUCTION

In 1997, Asahara et al. (4) characterized endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) as putative circulating stem cells that possess the capacity to participate in postnatal vasculogenesis and endothelial cell repair (31,33,36,39). Subsequently, two types of EPCs have been isolated from adult peripheral blood and are distinguished by both the chronological appearance of cell colonies in culture and by their in vitro and in vivo functional characteristics. “Early” EPCs appear after 4–7 days of culture as spindle-shaped colonies and have short, nonproliferative life spans of 3–4 weeks. “Late” EPCs or late outgrowth endothelial cells (OECs) appear in culture at 2–4 weeks, have a cobblestone appearance identical to that of mature endothelial cells, are highly proliferative, and contribute to new vessel formation in murine models of hindlimb ischemia (16,24,45).

More recently, Ingram and colleagues isolated and characterized a population of late outgrowth endothelial cells, termed endothelial colony forming cells (ECFCs), from human adult peripheral and umbilical cord blood using clonal plating techniques (18). ECFCs are organized in a hierarchy of progenitor stages that vary in proliferative potential and express endothelial surface antigens CD144 (VE-cadherin), CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule), and CD146, while lacking the hematopoietic cell marker CD45. When transplanted into collagen-fibronectin plugs in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, ECFCs formed intact, functioning vessels that contained murine red blood cells. This ability to be adoptively transplanted into a host and repopulate the mature cells of the intended lineage with donor cells is the sine qua non of a progenitor cell (44).

It has been previously proposed that the postnatal endothelium of blood vessels does not proliferate (1,2). In the adult, angiogenesis is generally restricted to the endometrium of the uterus during the reproductive life of females and is dependent on the replication of endothelial cells in the capillary plexus, an indication that resident microvascular endothelial cells retain proliferative capacity after birth (12,21). Using a single cell clonogenic assay, Alvarez and colleagues assessed the proliferative capacity of conduit artery and microvascular endothelium harvested from the rat pulmonary circulation (3). Approximately 60% of pulmonary artery endothelial cells were fully differentiated and did not divide, whereas 75% of microvascular endothelial cells isolated from lung divided, with half giving rise to colonies of more than 2,000 cells. These resident microvascular EPCs (RMEPCs) in in vitro and in vivo Matrigel assays formed ultrastructurally normal vessels de novo. These findings convincingly demonstrate that the microcirculation is a niche for highly proliferative, late outgrowth vasculogenic EPCs in the rat. However, such a repository has yet to be described in humans.

The fetal adnexa is composed of the placenta, fetal membranes, and umbilical cord and is a source of a variety of stem cell populations (7) that includes hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood (13,22,23,40), epithelial and mesenchymal stromal cells from amniotic membrane and fluid (5,38,46), and multipotent stem cells from the chorion (11,27,30). During fetal development, the placenta is a robust site of angiogenesis that begins as early as 21 days postconception and continues through gestation (9,10,42). The blood vessels of the placenta begin with the conduit vessels of the umbilical cord, continue into the arcades of the lobules of the deciduas, and terminate within the chorionic villi as capillaries and venules (19,34).

In this report, we describe a novel technique for the isolation of an as yet undescribed population of placenta derived ECFCs (PECFCs) from the microvasculature of chorionic villi. We further demonstrate that PECFCs have greater vasculogenic potential than cord blood-derived ECFCs (CBECFCs) in vivo, evidence that there are inherent functional differences between resident and circulating ECFC populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of Human Placentas and Vascular Lobes

Term placentas (n = 21; average weight 250–290 g) were collected from caesarean deliveries according to the approved protocol of the Indiana University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all donors. The umbilical cord vein was infused with 1,000 units of heparin (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) in 100 ml of 0.9% NaCl solution and drained. The placenta was washed with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) with 10 units of heparin/ml (Baxter) for 5 min. The branches of the umbilical artery and vein were dissected distally into the vascular lobules of the fetal placenta, terminating in the villous branches, removing four to five lobes per sample (15–25% of total placental volume). The vascular lobe was washed vigorously in HBSS for 10 min and then mechanically stripped of adherent decidual tissue with sterile gauze, leaving behind the exposed vessels. Umbilical cord blood (50–80 ml) was collected from the same specimens in a citrate phosphate dextrose solution.

Preparation of Mononuclear Cells From the Placenta Microvasculature and Umbilical Cord Blood

The villous blood vessels were mechanically minced in HBSS and the homogenate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 6 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with HBSS, enzymatically digested with collagenase type I (Worthington; Lakewood, NJ), washed with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) at 37°C for 2 h, and finally digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) plus 0.1% DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH; Mannheim, Germany) in DMEM at 37°C for 25–30 min. The cells were washed three times after each digestion with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT). After the second washing, the cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% FBS and passed through a 70-μm pore cell strainer. The filtrate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at 25°C and washed three times with 2% FBS in PBS solution. The cells were resuspended in 25 ml of 2% FBS in PBS solution, underlayed with 20 ml of Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Health Care, Piscataway, NJ), and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 30 min. The mononuclear cells (MNCs) were collected and washed twice with 2% FBS in PBS solution. The MNC fraction of cord blood was separated using Ficoll-Paque Plus and centrifugation as described previously (18).

Isolation of PECFCs and CBECFCs

MNCs were resuspended in 4 ml of endothelial basal media (EBM-2) (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen) [complete endothelial cell growth media (EGM-2)]. MNCs (5 × 107 cells/well) were seeded onto a well of a six-well tissue culture plate precoated with type 1 rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. After 24 h of culture, nonadherent cells and debris were aspirated, while adherent cells were washed once with complete EGM-2. Complete EGM-2 was then added to each well and changed daily. ECFCs were identified by distinct cobblestone morphology, circumscribed with a sterile cloning cylinder, and detached with trypsin-EDTA and resuspended in complete EGM-2. The resuspended ECFCs were replated in a 25-cm2 tissue culture flask precoated with type 1 rat tail collagen until 60–70% confluency, and then detached and incubated at 4°C for 30–60 min with primary anti-human murine monoclonal antibodies to CD144 conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and CD45 conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Using fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA), CD144+/CD45− cells were collected and plated on tissue culture flasks coated with type 1 rat tail collagen with complete EGM-2 for further expansion. CBECFCs were obtained after plating the MNC fraction and replating expanding colonies as previously described (18).

Immunophenotyping of PECFCs

Early passage (second or third) PECFCs were stained with different primary or isotype control antibodies at 4°C for 30 min in 100 μl PBS containing 2% FBS, washed twice with PBS, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by FACS (Becton Dickinson). The following primary anti-human murine monoclonal antibodies were used (all BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA unless otherwise indicated): CD31-PE, CD45-FITC, CD34-FITC, IgG1 isotype conjugated to FITC, IgG1 isotype conjugated to PE, CD105-FITC (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), CD144-PE (eBioscience), and kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) conjugated to PE (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Immunocytochemistry of PECFC Colonies

To assess CD144 expression, an expanding colony of PECFCs (∼1.5–2.0 × 103 cells) was detached and cultured on coverslips precoated with type 1 rat tail collagen. Cells were fixed with cold methanol (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 15 min at room temperature, rinsed with cold PBS twice, and stained overnight at 4°C with primary antibody (4 μg/ml) of murine anti-human CD144 (eBioscience) in PBS supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The coverslips were washed three times in PBS and incubated with chicken anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) at 1:100 dilution in PBS supplemented with 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The coverslips were washed three times with PBS and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), rinsed, and mounted onto slides. Phase contrast and fluorescence images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and a QImaging camera with QCapture Pro software (QImaging, Surrey, BC Canada). For cell staining with von-Willebrand factor (vWF) and CD31, 5 × 104 PECFCs were cultured in each well of a six-well tissue culture plate precoated with type 1 rat tail collagen in EGM-2. After 48 h, the attached cells were washed with PBS and fixed with cold methanol for 10 min at 4°C. Next, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 4°C. After washing the cells three times with cold PBS, the cells were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for1hatroom temperature. The cells were incubated with either primary antibody, anti-vWF rabbit antibody (A0082; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) or anti-human CD31 (clone JC70A; Dako) both diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature before washing three times with PBS. Further, the cells were incubated for 30 min with 1:2000 diluted secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21206; Invitrogen). Nuclear counterstaining was performed with 1 μg/ml DAPI (as described above) before the cells were inspected under the Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S fluorescent microscope as mentioned previously.

Matrigel Assay and Uptake of Acetylated LDL

Matrigel assays were performed as previously described (18). PECFCs (passage 3 or 4) were seeded onto 96-well tissue culture plates coated with 50 μl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at a density of 5,000 cells per well. Cells were observed for tubule formation after 24 h by visual microscopy with an inverted microscope at 40× magnification. To assess the ability of PECFCs to incorporate DiI-acetylated low-density lipoprotein (DiI-Ac-LDL), cells (passage 2 or 3) were seeded onto a collagen-coated coverslip and incubated in complete EGM-2 with 10 μg/ml of Dil-Ac-LDL (Invitrogen) overnight at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice and stained with 1 μg/ml of DAPI (Sigma). Cells were examined for uptake of Dil-Ac-LDL on DakoCytomation fluorescent mounting media (Dako) with a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S fluorescent microscope. Images were acquired using a QImaging camera and QCapture Pro software as mentioned previously.

HLA-DR Expression

Expression of major histocompatibility complex class II receptor human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) was assessed pre- and post-interferon-γ (IFN-γ) stimulation. PECFCs were plated onto tissue culture plates covered in type I rat tail collagen and exposed to recombinant human IFN-γ (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) at a concentration of 10 ng/ml. PECFC expression of HLA-DR was assessed by FACS analysis at 0, 4, 12, 24, and 48 h of exposure to IFN-γ compared to untreated PECFCs by labeling the cells with anti-HLA-DR FITC antibody (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Both groups were done in triplicate (n = 3). In addition to staining untreated PECFCs with the anti-HLA-DR FITC antibody after 48 h in culture, mouse IgG1 isotype conjugated to FITC (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was used as an isotype control.

Growth Kinetics

For the population doubling assays, 200,000 ECFCs of either placental or cord blood origin were plated into four separate T-75 tissue culture flasks (n = 4 for both cell types). During each passage, nucleated cells were enumerated using a trypan blue exclusion assay (Sigma) with a hemacytometer. During each subsequent passage, cells were enumerated to calculate growth kinetic curves, population doubling times (PDTs), and cumulative population doubling levels (CPDLs). The number of PDs occurring between passages was calculated according to the equation: PD = log2(CH/CS), where CH is the number of viable cells at harvest and CS is the number of cells seeded. The sum of all previous PDs determined the CPDL at each passage. The PDT was derived using the time interval between cell seeding and harvest divided by the number of PDs for that passage.

Single Cell Assays

Single cell assays were performed as previously described (18) with minor modifications. PECFCs (passage 2) were first incubated with CD 144-PE (eBioscience). The FACS Vantage Sorter (Becton Dickinson) was used to place a single CD144+ cell per well of a 96-well tissue culture plate precoated with type 1 collagen containing 200 μl of complete EGM-2. Cells were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2, and the medium was changed every 4 days with complete EGM-2. To determine the number of single dividing cells, wells were examined at day 14 of culture with a light microscope (40× magnification), and wells with two or more PECFCs were counted as positive for at least one cell division. To stratify colonies by proliferative capacity, cells were counted by light microscopy if there were fewer or equal to 50 cells per well. Wells containing more than 50 cells per well were trypsinized and counted using a hemacytometer. Progeny were then stratified based on the percentage of single cells that gave rise to endothelial cell clusters (EC, <50 cells), low proliferative potential colonies (LPP, 50–500 cells), and high proliferative potential colonies (HPP, >500 cells).

In Vivo Transplantation of PECFCs

Cellularized gel implants were cast with minor modifications (44). Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were used as a control cell population that would not grow vessels in vivo. A total of four different cells lines (n = 4) of both PECFCs and CBECFCs (both passage 3) each were used for the experiment, with each individual cell line tested in at least two separate gel plugs. Cultured PECFCs, CBECFCs, and human fibroblasts (1 × 106 cells/ml) were suspended in a solution consisting of 100 ng/ml human fibronectin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), 1.5 mg/ml rat tail collagen I (BD Biosciences), 1.5 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate (Sigma), 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane-sulfonic acid (HEPES) (Invitrogen), 10% FBS, 30% complete EGM-2 in EBM-2 with an adjusted pH of 7.4. The cellularized suspension was allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 30 min in a tissue culture plate, and covered with complete EGM-2 for overnight incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2. Gels were implanted into the flanks of anesthetized 18–20-week-old NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). On day 21, the mice were sacrificed with gas inhalation (CO2). The gels were removed, preserved in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, and evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry of PECFCs In Vivo and Vessel Enumeration

For each individual gel plug, multiple slides were made after sectioning with a keratome. To visualize human endothelial cells, sections were boiled in EDTA Retrieval buffer for 20 min, incubated with 2% H2O2 for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidases, and incubated with mouse on mouse (M.O.M.) IgG blocking reagent (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h. Sections were incubated with mouse anti-human CD31 antibodies (1:100; LabVision, Fremont, CA) for 1 h, followed by incubation with biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Vector) for 10 min. Antigen–antibody complexes were revealed by incubation with VECTASTAIN® ABC Reagent (HRP) for 10 min followed by exposure to DAB substrate (Sigma).

Vessel enumeration proceeded by dividing each slide’s section into four symmetric quadrants of known dimensions, with multiple photomicrographs taken for each quadrant. The number of CD31+ vessels in each quadrant was counted relative to the unit area. The total number of vessels counted relative to the total area measured was determined for each section of each gel plug, for which a mean value was obtained for each gel plug and subsequently each cell line. Final data are reported as mean number of vessels/mm2 ± SEM for four separate cell lines combined (n = 4) for each cell type (CBECFC or PECFC).

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data are represented as mean ± SEM. Comparison between groups of cells was performed with a two-tailed t-test on Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

Phenotypic and Functional Characterization of PECFCs

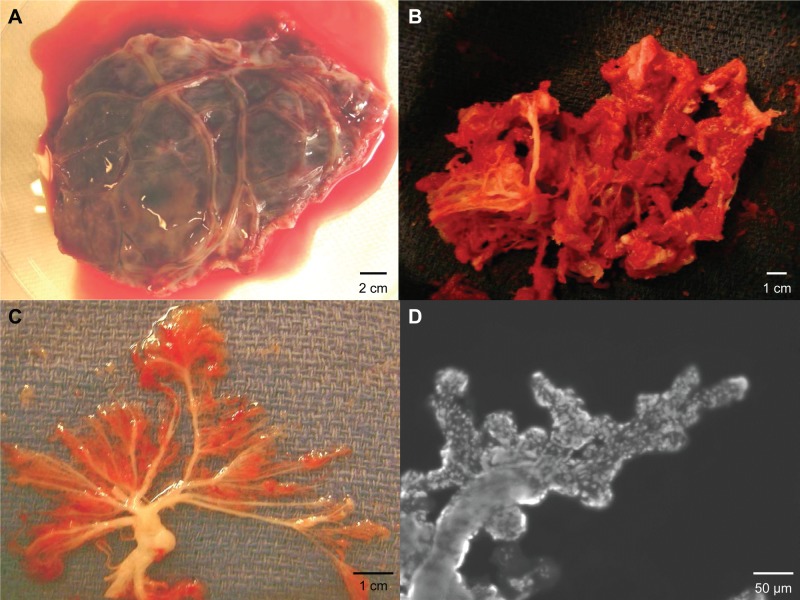

In this investigation, our objective was to determine if the microvascular network within the chorionic villi of the human placenta is a niche for ECFCs. To accomplish this task, we surgically exposed the terminal branches of the umbilical vessels as they traversed the chorionic membrane and isolated the vascular lobule of the fetal placenta (Fig. 1A). The adherent endometrial decidua was debrided from the vasculature (Fig. 1B), leaving behind the chorionic villi (Fig. 1C). For demonstration purposes, the terminal arteriolar branches were stained with Hoescht 33342 and imaged at 10× magnification (Fig. 1D), demonstrating the microvascular architecture of the processed samples.

Figure 1.

Isolation of a placenta vascular lobe and chorionic villi. (A) Vascular lobe after excision with intact chorionic membrane. Scale bar: 2 cm. (B) Vascular lobe after decidua is removed. Scale bar: 1 cm. (C) Photograph of the chorionic villi. Scale bar: 1 cm. (D) Representative photomicrograph of a terminal villus stained with Hoescht dye (10× magnification). Scale bar: 50 μm.

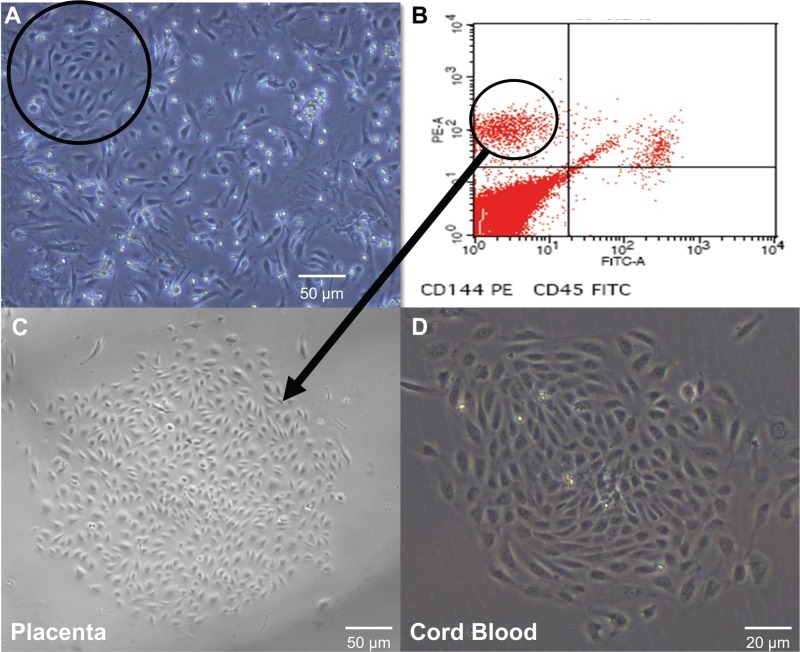

After mechanical mincing and enzymatic digestion, we then plated the MNC fraction obtained from the homogenate, and by day 3 of culture, expanding colonies with a cobblestone morphology appeared amidst a heterogeneous background of cells (Fig. 2A). These ECFCs were circumscribed with a cloning ring, and the contained cells were detached via trypsin. Our initial attempts of simply replating the detached cells were thwarted by contamination and rapid overgrowth of mesenchymal cells and fibroblasts. Based on cell surface markers specific for ECFCs (29,44), we collected CD144+/CD45− cells using FACS. This CD144+/CD45− population was replated and homogenous ECFC colonies appeared in culture by day 6 (Fig. 2C), identical in morphology to those of CBECFCs (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Isolation of placental endothelial colony-forming cells (PECFCs) using culture plating and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). (A) Colonies with cobblestone morphology appeared on day 3 of mononuclear cell (MNC) culture from the homogenate of vascular lobes. A cloning cylinder (circle) was placed and contained cells were detached and replated (40× magnification). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) After replating, the cells were grown to confluence and sorted for CD144+/CD45+ cells. (C) Replated CD144+/45− cells gave rise to homogenous ECFC colonies by day 6 of culture without contaminating mesenchymal cells (40× magnification). Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) cord blood ECFC (CBECFC) colony for comparison (100× magnification). Scale bar: 20 μm.

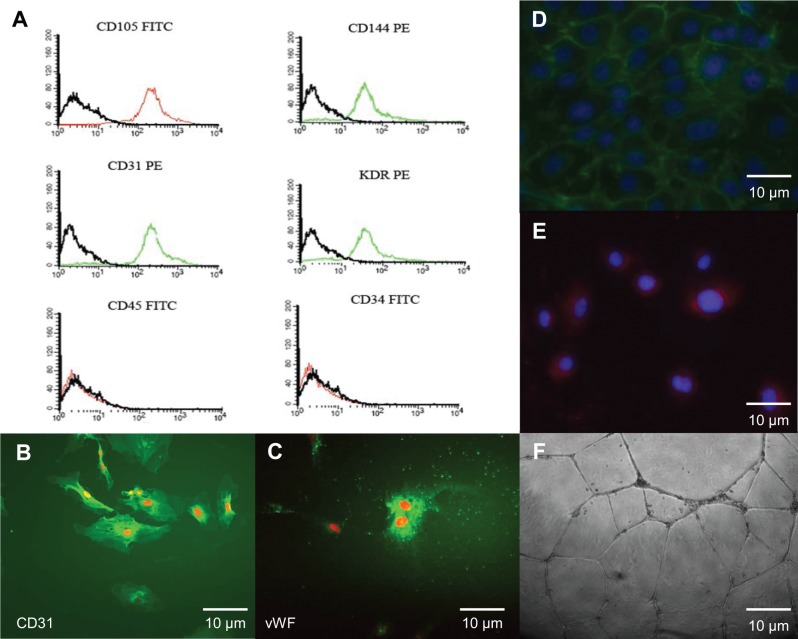

Immunophenotyping revealed that these colony-forming cells expressed the endothelial cell surface antigens CD31, CD144, CD105, and KDR and did not express the hematopoietic cell antigens CD34 or CD45 (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with the immunophenotype of ECFCs isolated from human umbilical cord blood (18,44). Immunocytochemistry of PECFCs revealed intense expression of vWF and CD31 (Fig. 3B, C). Likewise, antibodies for CD144 demonstrated robust PECFC expression of CD144 (Fig. 3D). Early passage PECFCs readily incorporated Dil-Ac-LDL (Fig. 3E) and rapidly formed tube-like structures in Matrigel after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 3F), both of which are functional characteristics of endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

Immunophenotyping and functional analysis of PECFCs. (A) Early passage PECFCs express CD31, CD144, CD105, and KDR (kinase insert domain receptor). However, they did not express hematopoietic cell antigens CD45 or CD34, which is consistent with the expression profile of CBECFCs. Likewise, PECFCs demonstrate intense expression of CD31 (B) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) (C), both of which are known characteristics of endothelial cells. (D) Expanding colonies of PECFCs express CD144 (green) on their cell membranes and take up DAPI (blue) in their nuclei. (E) PECFCs were able to incorporate Dil-Ac-LDL (blue) and form tubules in Matrigel (F) after 24 h. All images are at 400× magnification. All scale bars: 10 μm.

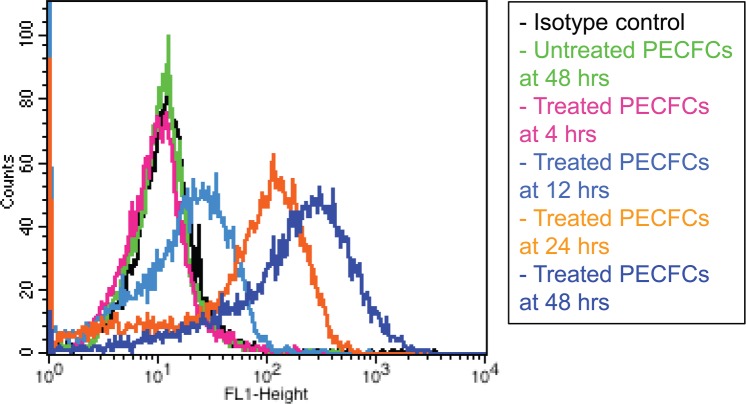

PECFCs were also examined for HLA-DR expression in the setting of IFN-γ stimulation. In the unstimulated state, PECFCs did not express MHC class II cell surface receptor HLA-DR. When exposed to IFN-γ, however, PECFCs demonstrated robust HLA-DR expression (Fig. 4) after 24 and 48 h of exposure (59.3 ± 1.6% and 68.9 ± 1.2% of cells, n = 3).

Figure 4.

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) stimulation assay. PECFCs were treated with 10 ng/ml of recombinant human IFN-γ over 48 h. PECFCs demonstrated robust human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR expression after 24 and 48 h of exposure (59.3 ± 1.6% and 68.9 ± 1.2% of cells respectively, n = 3). Both a treated isotype control and an untreated PECFC control at 48 h are shown for comparison. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Growth Kinetics of PECFCs

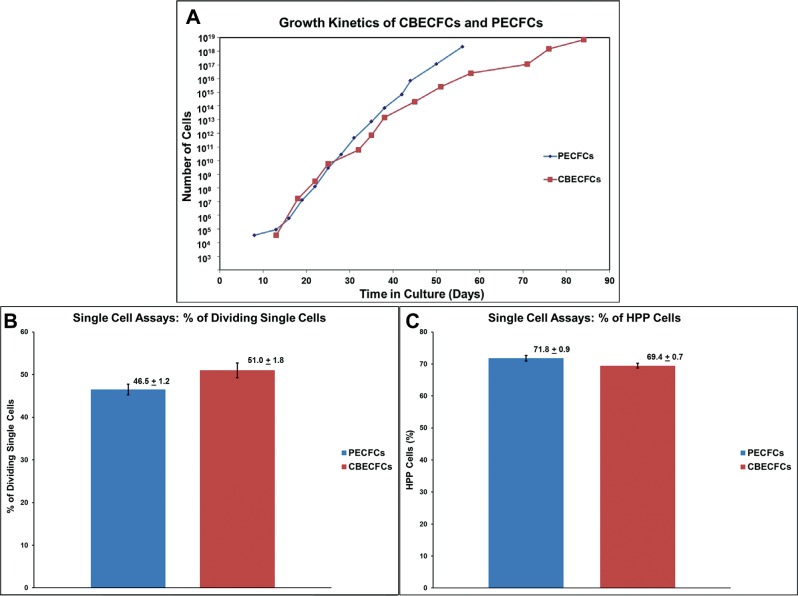

PECFCs underwent no less than 28.6 ± 6.0 cumulative population doublings (CPDL) before reaching senescence, which was inferior to CBECFCs (47.4 ± 3.2, p < 0.05, n = 4) (Fig. 5A). Using a single cell clonogenic assay, we compared the proliferative potential of PECFCs to CBECFCs isolated from the same donor. Nine 96-well plates were used in single cell assays for both cell types. A nearly similar percentage of single PECFCs (46.5 ± 1.2%) versus CBECFCs (51.0 ± 1.8%) underwent at least one division in cell culture (p = 0.07, n = 6) (Fig. 5B). Stratification of these matched PECFC and CBECFC samples into endothelial cell clusters, LPP-ECFCs and HPP-ECFCs, revealed similar distributions of clonogenic potential from placenta and cord blood. In fact, the tested PECFC populations contained a statistically equivalent number of HPP-ECFCs (71.8 ± 0.9%) as CBECFCs (69.4 ± 0.7%) (p = 0.07, n = 9) (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Growth kinetics and replicative potential of PECFCs and CBECFCs. (A) Growth kinetics plot for individual PECFC and CBECFC samples. PECFCs are capable of 28.6 ± 6.0 population doublings before becoming senescent, unlike the cumulative population doubling level (CPDL) of CBECFCs (47.4 ± 3.2, p < 0.05, n = 4). Despite this, PECFCs contain a near equivalent percentage of single cells capable of at least one division (B) (p = 0.07, n = 6) and contained a statistically equivalent percentage of high proliferative potential (HPP) cells as CBECFCs (C) (p = 0.07, n = 9). All data are reported as mean ± SEM.

PECFCs Form Chimeric Blood Vessels In Vivo

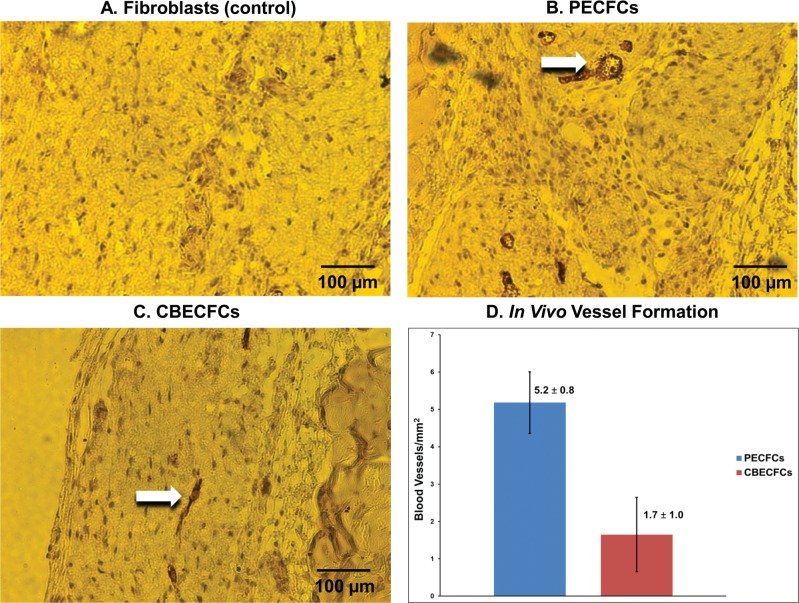

A defining characteristic of stem and progenitor cells is their ability to differentiate into mature functioning cells of the intended lineage (14,17,26,35). CBECFCs have been previously shown to develop functioning chimeric blood vessels in subcutaneous gel implants in immunodeficient mice (44). We assessed the vasculogenic capacity of PECFCs using the same assay and by quantifying intact blood vessels that stained positive for human CD31. Vessels staining positive for human CD31 were counted in four independent experiments for each PECFC and CBECFC cell line. PECFCs formed significantly more vessels than did CBECFCs (5.2 ± 0.8 vs. 1.7 ± 1.0, p < 0.05, n = 4). Representative photomicrographs and enumeration of vessels derived from PECFCs and CBECFCs are shown (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Representative photomicrographs of cellularized gel implants, with blood vessels labeled for anti-human CD31. Arrows denote chimeric blood vessels containing mouse red blood cells (RBCs) in gel implants polymerized with PECFCs (B) (200× magnification) and CBECFCs (C) (200× magnification). Human fibroblasts (control) did not develop vessels (A) (200× magnification). Scale bars: 100 μm. PECFCs formed significantly more human CD31+ vessels/mm2 (5.2 ± 0.8) in collagen gel implants than CBECFCs (1.7 ± 1.0) (p < 0.05, n = 4) (D). Data reported as mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

ECFCs were first isolated from umbilical cord blood, human adult peripheral blood, and from rat pulmonary artery and lung microvascular endothelium (3,18,44). ECFCs are functionally distinct from monocyte-derived endothelial progenitor cells as ECFCs have been shown to contain a proliferative hierarchy of clones and are capable of forming blood vessels in vivo (18,44). Intrigued by these qualities of circulating ECFCs from human cord and peripheral blood and motivated by Alvarez et al.’s (3) description of RMEPCs from the rat pulmonary microvasculature, it was our objective to determine if the endothelium in the chorionic villi of human placenta contained ECFCs and if these cells were functionally different from circulating CBECFCs. Here, we provide a descriptive analysis of placental resident ECFCs using the same colony forming assays originally described by Ingram et al. (18). Our approach was modified though, as initially we plated the cellular homogenate obtained after mincing and enzymatically digesting ECFCs. However, the culture plates were rapidly overgrown with spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells. We refined our technique for isolation further by detaching expanding colonies of cells with cobblestone morphologies, replating those detached cells, and then selecting for CD144+ cells and replating once again for purity. This produced a homogenous population of cells that are phenotypically identical to CBECFCs and have nearly equivalent proliferative potential. One concern that we have is the effect of FACS sorting on PECFC viability that may have had a negative impact on our proliferative assays as compared to CBECFCs that did not undergo FACS sorting prior to experimentation. However, FACS sorting for PECFCs was necessary due to the overwhelming presence of mesenchymal cells in the PECFC MNC fraction, whereas CBECFCs are more readily isolated without such concerns (17,18).

The role of circulating ECFCs has yet to be determined. Circulating mature endothelial cells are rarely found in normal healthy individuals and are a marker of vascular damage, remodeling, and dysfunction (6,25,32,41). Our group has analyzed circulating ECFCs from adult patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and healthy subjects. Our experiments found great variability in both quantity and proliferative potential between the two groups. Overall, there was a trend for increased number and proliferative capacity of circulating ECFCs in patients with PAD (unpublished data). Whether these cells are sloughed as a result of injury or mobilized to repair injury is the focus of ongoing investigations. The same conundrum exists with circulating CBECFCs. CBECFCs may represent either sloughed cells from the endothelium of the placental chorionic villi, blood vessels of the fetus, or mobilized progenitor cells homing to areas of vasculogenesis. Most interestingly, the results of our investigation show that resident PECFCs gave rise to significantly more vessels in vivo than did circulating CBECFCs. Based on the rapid growth of the placenta microvascular bed during fetal development, we would expect the vessels in the chorionic villi to be a niche of highly vasculogenic progenitor cells. There are distinct limitations in this report in that both CBECFCs and PECFCs were subjected to significant manipulation during colony expansion and plating, as well as exposure to culture media with vascular growth factors both of which have the potential to incite perturbations in cellular function. Although the experiments were designed with the intent to compare the two cell populations in equivalent conditions, these results should not be construed as to reflect the behavior of either cell population in vivo.

There has been significant interest in regenerative therapies using autologous and allogeneic progenitor cells from a variety of tissue sources (8,15,20,28,37,43). Umbilical cord blood and the extra-embryonic membranes of the placenta are ideal sources of progenitor cells as these tissues are discarded as medical waste and the ethical concerns facing embryonic stem cells are avoided. A drawback with CBECFCs is the limited volume and the relatively low yield of ECFCs from cord blood. The yield of ECFCs per milliliter of MNCs derived from the placental vascular lobes was three- to fourfold greater than the yields derived from MNC fractions of cord blood (data not shown) and only 25–30% of the total placental volume from each placenta was used for isolation of PECFCs used in these experiments. Thus, the placenta chorionic villi represents an abundant source of ECFCs that could provide a therapeutic dose of cells, avoiding the associated potential for contamination and karyotype abnormalities that occur with expansion of clones. It is also important to note that while PECFCs did not express HLA-DR immediately after plating, exposure to IFN-γ resulted in robust PECFC expression of HLA-DR. Hence, this may limit the utility of PECFCs for autologous applications. Despite this, we envision that PECFCs may provide some benefit in neonatal cerebral ischemia or for tissue banking for future use in treating cardiovascular disease.

To summarize, the endothelium of the chorionic villi of the human placenta is a niche for resident PECFCs. Circulating CBECFCs and resident PECFCs are both highly proliferative, but PECFCs possess significantly greater vasculogenic capacity than CBECFCs and highlights the clinical utility of PECFCs. The potential volume of PECFCs that can be harvested from a single placenta would provide a sufficient dose of cells without expansion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Cryptic Masons’ Medical Research Foundation, and the IUPUI Vascular and Cardiac Center for Adult Stem Cell Therapy. We acknowledge the In Vivo Therapeutics Core ofthe Indiana University Simon Cancer Center as well as the nursing staff and Dr. Arthur Baluyut at the St. Vincent Hospital (Indianapolis, IN) for providing umbilical cord blood samples for this study. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aird W. C. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: I. Structure, function, and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 100(2):158–173; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aird W. C. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circ. Res. 100(2):174–190; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez D. F.; Huang L.; King J. A.; El Zarrad M. K.; Yoder M. C.; Stevens T. Lung microvascular endothelium is enriched with progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 294(3):L419–430; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asahara T.; Murohara T.; Sullivan A.; Silver M.; van der Zee R.; Li T.; Witzenbichler B.; Schatteman G.; Isner J. M. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 275(5302):964–967; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bieback K.; Kern S.; Kluter H.; Eichler H. Critical parameters for the isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells 22(4):625–634; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonello L.; Basire A.; Sabatier F.; Paganelli F.; Dignat-George F. Endothelial injury induced by coronary angioplasty triggers mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4(5):979–981; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borlongan C. V.; Parolini O. International placenta stem cell society: Planting the seed for placenta stem cell research. Cell Transplant. 19(5):507–508; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cargnoni A.; Gibelli L.; Tosini A.; Signoroni P. B.; Nassuato C.; Arienti D.; Lombardi G.; Albertini A.; Wengler G. S.; Parolini O. Transplantation of allogeneic and xenogeneic placenta-derived cells reduces bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Cell Transplant. 18(4):405–422; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chien C. C.; Yen B. L.; Lee F. K.; Lai T. H.; Chen Y. C.; Chan S. H.; Huang H. I. In vitro differentiation of human placenta-derived multipotent cells into hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cells 24(7):1759–1768; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demir R.; Kaufmann P.; Castellucci M.; Erbengi T.; Kotowski A. Fetal vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in human placental villi. Acta Anat. 136(3):190–203; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukuchi Y.; Nakajima H.; Sugiyama D.; Hirose I.; Kitamura T.; Tsuji K. Human placenta-derived cells have mesenchymal stem/progenitor cell potential. Stem Cells 22(5):649–658; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gargett C. E.; Rogers P. A. Human endometrial angiogenesis. Reproduction 121(2):181–186; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gluckman E.; Broxmeyer H. A.; Auerbach A. D.; Friedman H. S.; Douglas G. W.; Devergie A.; Esperou H.; Thierry D.; Socie G.; Lehn P.; Cooper S.; English D.; Kurtzberg J.; Bard J.; Boyse E. A. Hematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with Fanconi’s anemia by means of umbilical-cord blood from an HLA-identical sibling. N. Engl. J. Med. 321(17):1174–1178; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirschi K. K.; Ingram D. A.; Yoder M. C. Assessing identity, phenotype, and fate of endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28(9):1584–1595; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang G. P.; Pan Z. J.; Jia B. B.; Zheng Q.; Xie C. G.; Gu J. H.; McNiece I. K.; Wang J. F. Ex vivo expansion and transplantation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells supported by mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord blood. Cell Transplant. 16(6):579–585; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hur J.; Yoon C. H.; Kim H. S.; Choi J. H.; Kang H. J.; Hwang K. K.; Oh B. H.; Lee M. M.; Park Y. B. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24(2):288–293; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ingram D. A.; Mead L. E.; Moore D. B.; Woodard W.; Fenoglio A.; Yoder M. C. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 105(7):2783–2786; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ingram D. A.; Mead L. E.; Tanaka H.; Meade V.; Fenoglio A.; Mortell K.; Pollok K.; Ferkowicz M. J.; Gilley D.; Yoder M. C. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood 104(9):2752–2760; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaufmann P.; Mayhew T. M.; Charnock-Jones D. S. Aspects of human fetoplacental vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. II. Changes during normal pregnancy. Placenta 25(2–3):114–126; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J. Y.; Song S. H.; Kim K. L.; Ko J. J.; Im J. E.; Yie S. W.; Ahn Y. K.; Kim D. K.; Suh W. Human cord blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells and their conditioned media exhibit therapeutic equivalence for diabetic wound healing. Cell Transplant. 19(12):1635–1644; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. King J.; Hamil T.; Creighton J.; Wu S.; Bhat P.; McDonald F.; Stevens T. Structural and functional characteristics of lung macro- and microvascular endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc. Res. 67(2):139–151; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurtzberg J.; Laughlin M.; Graham M. L.; Smith C.; Olson J. F.; Halperin E. C.; Ciocci G.; Carrier C.; Stevens C. E.; Rubinstein P. Placental blood as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation into unrelated recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 335(3):157–166; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin R. Z.; Dreyzin A.; Aamodt K.; Dudley A. C.; Melero-Martin J. M. Functional endothelial progenitor cells from cryopreserved umbilical cord blood. Cell Transplant. 20(4):515–522; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin Y.; Weisdorf D. J.; Solovey A.; Hebbel R. P. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. J. Clin. Invest. 105(1):71–77; 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mancuso P.; Burlini A.; Pruneri G.; Goldhirsch A.; Martinelli G.; Bertolini F. Resting and activated endothelial cells are increased in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Blood 97(11):3658–3661; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melero-Martin J. M.; Khan Z. A.; Picard A.; Wu X.; Paruchuri S.; Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 109(11):4761–4768; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miki T.; Lehmann T.; Cai H.; Stolz D. B.; Strom S. C. Stem cell characteristics of amniotic epithelial cells. Stem Cells 23(10):1549–1559; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyamoto M.; Yasutake M.; Takano H.; Takagi H.; Takagi G.; Mizuno H.; Kumita S.; Takano T. Therapeutic angiogenesis by autologous bone marrow cell implantation for refractory chronic peripheral arterial disease using assessment of neovascularization by 99mTc-tetro-fosmin (TF) perfusion scintigraphy. Cell Transplant. 13(4):429–437; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagano K.; Yoshida Y.; Isobe T. Cell surface biomarkers of embryonic stem cells. Proteomics 8(19):4025–4035; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ochsenbein-Kolble N.; Bilic G.; Hall H.; Huch R.; Zimmermann R. Inducing proliferation of human amnion epithelial and mesenchymal cells for prospective engineering of membrane repair. J. Perinat. Med. 31(4):287–294; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peichev M.; Naiyer A. J.; Pereira D.; Zhu Z.; Lane W. J.; Williams M.; Oz M. C.; Hicklin D. J.; Witte L.; Moore M. A.; Rafii S. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood 95(3):952–958; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Quilici J.; Banzet N.; Paule P.; Meynard J. B.; Mutin M.; Bonnet J. L.; Ambrosi P.; Sampol J.; Dignat-George F. Circulating endothelial cell count as a diagnostic marker for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 110(12):1586–1591; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reyes M.; Dudek A.; Jahagirdar B.; Koodie L.; Marker P. H.; Verfaillie C. M. Origin of endothelial progenitors in human postnatal bone marrow. J. Clin. Invest. 109(3):337–346; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reynolds L. P.; Redmer D. A. Angiogenesis in the placenta. Biol. Reprod. 64(4):1033–1040; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shepherd B. R.; Enis D. R.; Wang F.; Suarez Y.; Pober J. S.; Schechner J. S. Vascularization and engraftment of a human skin substitute using circulating progenitor cell-derived endothelial cells. FASEB J. 20(10):1739–1741; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shintani S.; Murohara T.; Ikeda H.; Ueno T.; Sasaki K.; Duan J.; Imaizumi T. Augmentation of postnatal neo-vascularization with autologous bone marrow transplantation. Circulation 103(6):897–903; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun Y.; Feng Y.; Zhang C.; Cheng X.; Chen S.; Ai Z.; Zeng B. Beneficial effect of autologous transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells on steroid-induced femoral head osteonecrosis in rabbits. Cell Transplant. 20(2):233–243; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsai M. S.; Lee J. L.; Chang Y. J.; Hwang S. M. Isolation of human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from second-trimester amniotic fluid using a novel two-stage culture protocol. Hum. Reprod. 19(6):1450–1456; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Urbich C.; Dimmeler S. Endothelial progenitor cells: Characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ. Res. 95(4):343–353; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wagner J. E.; Rosenthal J.; Sweetman R.; Shu X. O.; Davies S. M.; Ramsay N. K.; McGlave P. B.; Sender L.; Cairo M. S. Successful transplantation of HLA-matched and HLA-mismatched umbilical cord blood from unrelated donors: Analysis of engraftment and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 88(3):795–802; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Widemann A.; Sabatier F.; Arnaud L.; Bonello L.; Al-Massarani G.; Paganelli F.; Poncelet P.; Dignat-George F. CD146-based immunomagnetic enrichment followed by multiparameter flow cytometry: A new approach to counting circulating endothelial cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 6(5):869–876; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yen B. L.; Huang H. I.; Chien C. C.; Jui H. Y.; Ko B. S.; Yao M.; Shun C. T.; Yen M. L.; Lee M. C.; Chen Y. C. Isolation of multipotent cells from human term placenta. Stem Cells 23(1):3–9; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yerebakan C.; Sandica E.; Prietz S.; Klopsch C.; Ugur-lucan M.; Kaminski A.; Abdija S.; Lorenzen B.; Boltze J.; Nitzsche B.; Egger D.; Barten M.; Furlani D.; Ma N.; Vollmar B.; Liebold A.; Steinhoff G. Autologous umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation preserves right ventricular function in a novel model of chronic right ventricular volume overload. Cell Transplant. 18(8):855–868; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yoder M. C.; Mead L. E.; Prater D.; Krier T. R.; Mroueh K. N.; Li F.; Krasich R.; Temm C. J.; Prchal J. T.; Ingram D. A. Redefining endothelial progenitor cells via clonal analysis and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell principals. Blood 109(5):1801–1809; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yoon C. H.; Hur J.; Park K. W.; Kim J. H.; Lee C. S.; Oh I. Y.; Kim T. Y.; Cho H. J.; Kang H. J.; Chae I. H.; Yang H. K.; Oh B. H.; Park Y. B.; Kim H. S. Synergistic neovascularization by mixed transplantation of early endothelial progenitor cells and late outgrowth endothelial cells: The role of angiogenic cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Circulation 112(11):1618–1627; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao P.; Ise H.; Hongo M.; Ota M.; Konishi I.; Nikaido T. Human amniotic mesenchymal cells have some characteristics of cardiomyocytes. Transplantation 79(5):528–535; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]