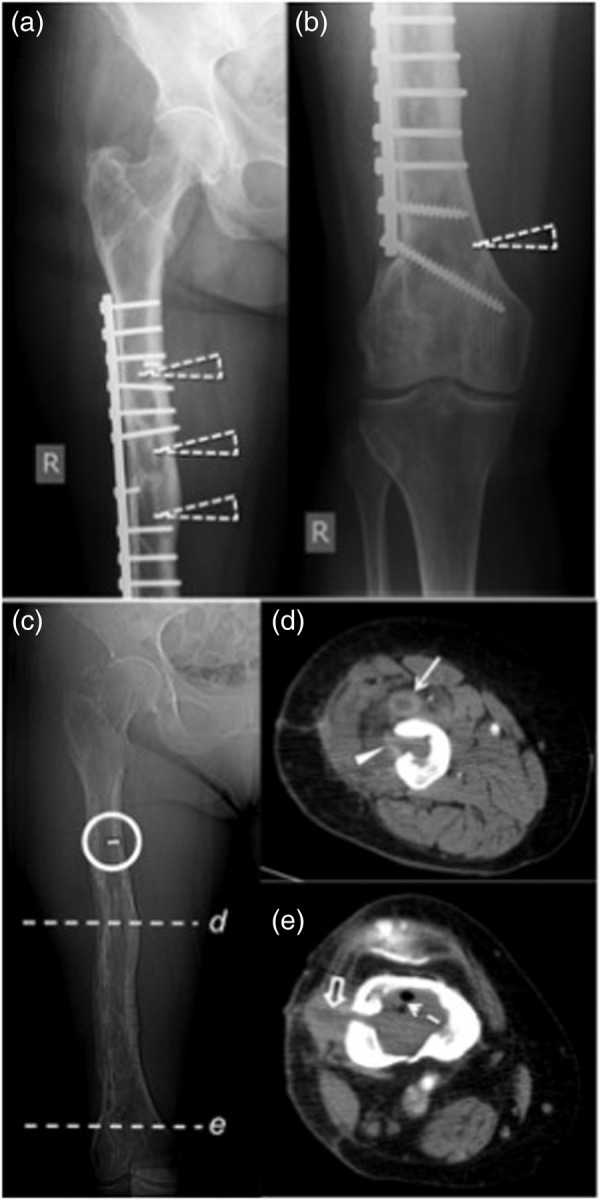

A 54-year-old woman sustained an open fracture of the right femoral shaft after a bicycle accident in 1985. Several operations were performed, the last including internal fixation using a plate and screws. In 2002, acute diverticulitis was treated with ciprofloxacin/metronidazole. In 2007, she presented with pain and swelling of the right thigh. Plain radiographs showed radiolucent femoral areas (Figure 1a and b). Treatment was with debridement and removal of orthopedic hardware except for a difficult-to-remove screw fragment. Gentamicin beads were temporarily placed along the femur. Eight intraoperative specimens showed no growth after 10 days. Because of poor wound healing, a computed tomography scan was obtained, showing a sinus tract, femoral cortical defects, and intramedullary air (Figure 1c–e). Additional debridement was done; cultures of intraoperative biopsy specimens again remained sterile. Amoxicillin/clavulanate was prescribed for 2 weeks, and ciprofloxacin/rifampin was prescribed for 10 weeks.

Figure 1.

Chronic femoral osteomyelitis demonstrated by plain radiographs and computed tomography in 2007. Anterior-posterior plain film projections (a and b) show the orthopedic hardware and several radiolucencies within the femur (open dashed arrowheads). Scout image of the computed tomography (c) shows the remnant of a screw (circle); location of axial images performed with intravenous contrast are marked with lines (d and e). Image (d) demonstrates an abscess formation ventral to the midportion of the femur within the vastus intermedius muscle (arrow), extending to the bone marrow (arrowhead) through a borehole defect. (e) In the distal femur, intramedullary gas (dashed arrow) within a fluid collection is shown, extending through a lateral cortical defect and a sinus tract (open arrow) to the skin.

In 2008, local pain and swelling reappeared. Magnetic resonance imaging showed chronic osteomyelitis, contiguous with the screw fragment. This was removed, and the medullary cavity was reamed from proximal to distal [1]. Seven intraoperative specimens showed no growth after 10 days. Amoxicillin/clavulanate was prescribed for 3 months. In 2010, local swelling reappeared. Surgical bone biopsies showed no growth at 10 days. Bacterial broad-range 16S rRNA gene polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done, and sequence analysis showed a Tissierella species. At 3 weeks, 3 of 7 biopsies showed pure anaerobic growth of a Tissierella species in brain-heart-infusion broth. The isolate was positive for arginine dihydrolase, alkaline phosphatase, and pyroglutamic acid arylamidase (rapid ID32A test strip; bioMérieux, Switzerland) and leucine arylamidase, tyrosine arylamidase, phenylalanine arylamidase, and pyroglutamic acid arylamidase (VITEK, bioMérieux, Switzerland). Identification was done by sequencing almost the entire 16S rRNA gene. The 1434 base pair (bp) sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. KR781503) showed 1 mismatch over a 1371 bp segment compared with reference Tissierella carlieri strain LBN 292 (99.9% sequence similarity) that was recently described [2]. Susceptibility testing results are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Clinical Tissierella carlieri Strain to 10 Antimicrobial Agents*

| Antimicrobial Agent | MIC (µg/L) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | <0.002 | Susceptible |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | <0.016 | Susceptible |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | <0.016 | Susceptible |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.016 | Susceptible |

| Imipenem | 0.002 | Susceptible |

| Meropenem | <0.002 | Susceptible |

| Ertapenem | <0.002 | Susceptible |

| Clindamycin | 64 | Resistant |

| Metronidazol | <0.016 | Susceptible |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.064 | Susceptible |

* Susceptibility testing was done with the E-test system (bioMérieux). Interpretation of MICs was performed according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines (V5.0, 2015-01-01) using the clinical breakpoint table for Gram-positive anaerobes. Ceftriaxone and moxifloxacin susceptibility was interpreted applying CLSI standards (M100-S25 Vol. 35 No. 3).

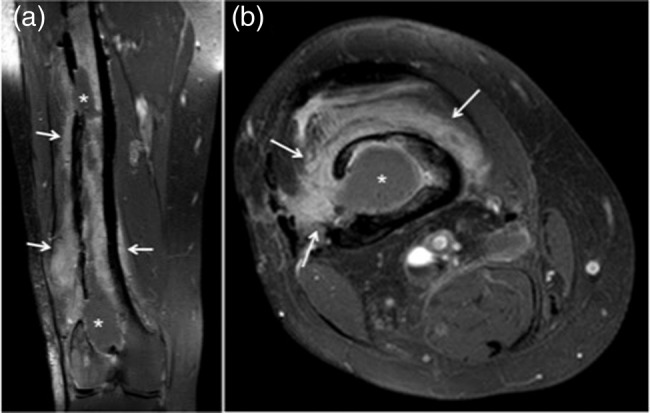

No antimicrobial therapy was started because the pathogenic role of the Tissierella was unclear, and the wound had healed. In November 2011, local pain and discharge from the scar were noted. Imaging revealed osteomyelitis (Figure 2), including an area with sequestra in the lateral femoral condyle, an area not debrided until then. In January 2012, the distal three fifths of the medullary cavity were reached by a long cortical window from lateral. Intraoperatively, a sinus tract and several bony sequestra were found. Extensive intramedullary debridement was performed, and a cement spacer containing gentamicin/clindamycin/meropenem beads was temporarily placed. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures from 16 surgical specimens remained sterile after 6 weeks; broad-spectrum PCR again showed the Tissierella species in 2 of 2 specimens. The patient completed a 12-week course of amoxicillin and remains asymptomatic >3 years later (November 2015).

Figure 2.

Chronic osteomyelitis demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in 2011. Coronal (a) and axial (b), T1-weighted spectral attenuated inversion recovery sequences reveal several intramedullary fluid collections (asterisks) with surrounding confluent bone marrow edema and adjacent diffuse contrast enhancement in the soft tissue (arrows).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the second case of monomicrobial human infection and the first reported case of chronic, orthopedic implant-associated osteomyelitis due to Tissierella species. The isolate was likely the causative pathogen, based on clinical, radiological, and intraoperative evidence of chronic osteomyelitis, growth in pure culture in multiple surgical bone specimens, and congruent 16S rRNA sequences in 2010 and 2012.

Tissierella praeacuta (synonym: Clostridium hastiforme [3]) has been recovered from humans on 3 previous occasions [4–6], but in only 1 patient with eyelid necrosis [5] was there pure growth in culture. In our patient, it is unclear how T carlieri gained access to the femur. Prior open fracture and concomitant anaerobic infection elsewhere in the body (with presumable transient bacteremia) have been frequently noted in patients with anaerobic osteomyelitis [7–9]. The open fracture (requiring insertion of orthopedic hardware) and the diverticulitis occurred 22 and 5 years before evidence of osteomyelitis in our patient, respectively, so their pathogenic roles remain speculative. In a recent series including 61 patients with anaerobic bone and joint infections, Walter et al [10] noted several common features present in our patient, including a high proportion of implant-associated cases, delayed presentation (≥6 months postoperatively), and a high relapse rate.

CONCLUSIONS

Most cases of anaerobic osteomyelitis have been polymicrobial [7–10]. In our patient, monomicrobial infection with a T carlieri isolate might have been selected for by previous, prolonged antimicrobial treatments in the setting of persistent dead bone [7–9]. Debridement of dead bone is a key feature of successful management [11–13]. Our case also suggests that, in culture-negative osteomyelitis cases, attention should be paid to careful specimen collection and prolonged anaerobic culture. Microbiological diagnosis may require 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis based on broad-range PCR. These results can then be used to guide optimal culture method [14].

Acknowledgments

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Ochsner PE, Brunazzi MG. Intramedullary reaming and soft tissue procedures in treatment of chronic osteomyelitis of long bones. Orthopedics 1994; 17:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alauzet C, Marchandin H, Courtin P et al. Multilocus analysis reveals diversity in the genus Tissierella: description of Tissierella carlieri sp. nov. in the new class Tissierellia classis nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 2014; 37:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae JW, Park JR, Chang YH et al. Clostridium hastiforme is a later synonym of Tissierella praeacuta. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:947–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson AP, Montgomery JR, South MA, Wilson R. A special report: four-year study of a boy with combined immune deficiency maintained in strict reverse isolation from birth. Pediatr Res 1977; 11:63–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyon DB, Lemke BN. Eyelid gas gangrene. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1989; 5:212–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox K, Al-Rawahi G, Kollmann T. Anaerobic brain abscess following chronic suppurative otitis media in a child from Uganda. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2009; 20:e91–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raff MJ, Melo JC. Anaerobic osteomyelitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57:83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis RP, Sutter VL, Finegold SM. Bone infections involving anaerobic bacteria. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57:279–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brook I, Frazier EH. Anaerobic osteomyelitis and arthritis in a military hospital: a 10-year experience. Am J Med 1993; 94:21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter G, Vernier M, Pinelli PO et al. Bone and joint infections due to anaerobic bacteria: an analysis of 61 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33:1355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Pozo JL, Patel R. Clinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic joints. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:e1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez MC, Sebti R, Hassoun P et al. Osteomyelitis of the patella caused by Legionella anisa. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:2791–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]