Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the factors associated with health services utilization using Andersen's behavioral model.

Methods

We collected Korea Health Panel data between the years 2010 and 2012 from the consortium of the National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, and analyzed the data to determine the outpatients and inpatients of health services utilization.

Results

Health services utilization was more significantly explained by predisposing and need factors than enabling factors. The outpatients were examined more specifically; sex, age, and marital status as predisposing factors, and chronic illness as a need factor were the variables that had significant effects on health-services-utilization experience. The inpatients were examined more specifically: sex, age, and marital status in predisposing factors; education level, economic activities, and insurance type in enabling factors; and chronic illness and disability status in need factors were the significant variables having greater effects on health-services-utilization experience.

Conclusion

This study suggests the practical implications for providing health services for outpatients and inpatients. Moreover, verifying the general characteristics of outpatients and inpatients by focusing on their health services utilization provides the baseline data for establishing health service policies and programs with regard to the recently increasing interest in health services.

Keywords: Andersen's behavioral model, health services utilization, inpatient, Korea health panel, outpatient

1. Introduction

The medical security system in Korea has achieved remarkable quantitative growth over a relatively short period. However, income inequality intensified in the overall society during the International Monetary Fund crisis, which accordingly engendered health-equity issues. Differentiation occurs at the basic health level, since health needs and achievements vary by income, education level, and employment security; there are also gaps in health services accessibility [1].

Health services utilization is not created by a simple health condition, but is a final outcome after creating health needs based on socioeconomic factors 2, 3. This becomes the foundation of theories on health needs and is important when determining the aspects of health services utilization. Moreover, in the behavioral model, an individual's demographic, sociostructural, and economic factors affect health services utilization along with disease factors 4, 5, 6. Using this theoretical background, multiple studies have examined individuals' socioeconomic factors and the characteristics of the communities to which the individuals belong, in addition to the disease factors, to analyze health services utilization. The results suggest that health services utilization is basically motivated by individual illness, but the quality and quantity of health services utilization vary significantly based on socioeconomic factors, such as income or health-insurance status 7, 8.

Meanwhile, the health and medical field conventionally uses the health belief and Andersen theoretical models to explain services utilization 9, 10, 11. Of the two, the Andersen model, which explains that the services utilization is determined by predisposing, enabling, and need factors, is used broadly as a theoretical model that analyzes predictors of health services utilization. This may also be a suitable model when exploratory research is needed due to lack of previous studies on outpatient and inpatient health services utilization, as in this study [12].

To research how the relevance of categorized factors with health services utilization varies, Andersen and Newman [13] compared the size of factors affecting health services utilization, such as inpatient and outpatient services, by combining the results of Andersen's individual research [14]. As a result, both inpatient and outpatient services were strongly affected by the disease factors that represent health conditions, whereas predisposing factors and enabling factors had medium effects [10]. For the predisposing factors, social factors, such as education and employment status, had significant effects on inpatient services, implying that outpatient than inpatient services may respond more sensitively to an individual's socioeconomic position 5, 15, 16.

This study will verify the general experiences of outpatient and inpatient services in Korea, and explore and examine the predictors that affect the health services utilization by applying the Andersen model. This study has significance in that it can empirically verify whether the Andersen model can be applied to outpatients and inpatients as in overseas studies, and can clarify the predictors for health-services-utilization experiences in Korea that are measured objectively. The specific research questions are as follows: (1) What are the general characteristics related to health-services-utilization experiences of outpatients and inpatients? and (2) How do predisposing, enabling, and need factors affect the health-services-utilization experiences of outpatients and inpatients?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research model

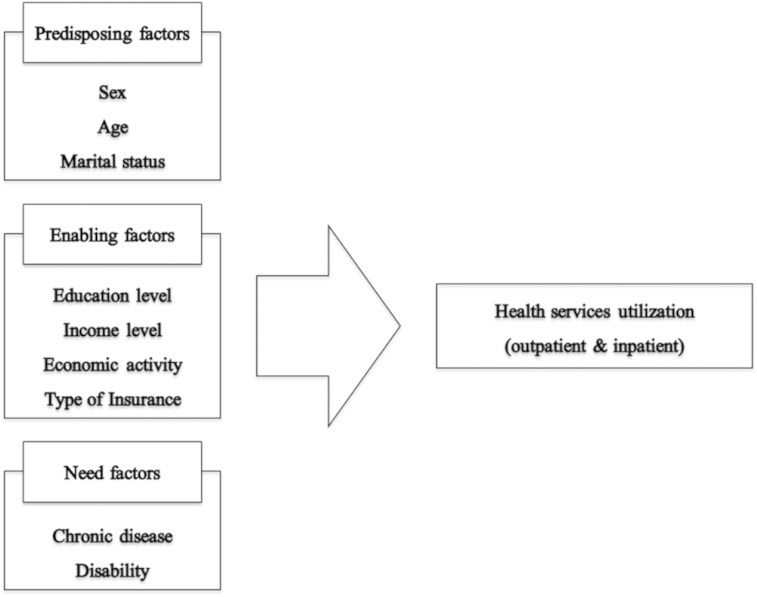

This study examined the predisposing, enabling, and need factors that determine the overall health-services-utilization experiences of outpatients and inpatients with the aforementioned Andersen model as the theoretical framework. The research model for analysis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2.2. Data source

This study used the source data of the Korea Health Panel jointly collected by the consortium of the National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. The Korea Health Panel included information, such as health-services-utilization behaviors and health-care expenditures. Moreover, national representativeness was secured by extracting samples from 90% complete enumeration data of the 2006 Population and Housing Census. Sampling was done by stratified cluster sampling; the first step consisted of extracting sampling enumeration districts (clusters) based on the stratification variables (such as 16 cities, provinces, dongs, eups, myeons, and gus). The second step consisted of extracting sample households within the enumeration districts. The data were provided after completing the “Data Use Agreement” on the Korea Health Panel website. The 3 years' worth of data used for this study were panel data from 2010 to 2012. This study verified the accessibility to health services in the entire population group. Therefore, it included 13,734 participants from all household members surveyed in the Korea Health Panel.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study was health services utilization. In the analysis, it was divided into outpatient and inpatient services. Whether one utilized health services was calculated by the experiences of using outpatient and inpatient services at least once in the past year. Table 1 explains the dependent variable used in this study.

Table 1.

Definition of dependent variables.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Outpatient | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes | |

| Inpatient | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes |

2.3.2. Independent variables

This study adopted Andersen's behavioral model widely known for verifying the accessibility to health services. The Andersen model consisted of predisposing, enabling, and need factors [17]. Predisposing factors refer to basic characteristics of the population; in this study, they included sex, age, and marital status. Enabling factors refer to conditions that may be changed by an individual and social efforts; in this study, they included education and income level, economic activities, form of medical security, and private-insurance status 18, 19. Need factors were the most directly associated with the accessibility to health services and reflect disease characteristics [20]. In this study, they included chronic disease and disability status. Table 2 shows the independent variables used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Classification and definition of independent variables.

| Variable | Definition | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | Gender | 0 = Male | Male |

| 1 = Female | |||

| Age | |||

| Marital status | 0 = No spouse | No spouse | |

| 1 = Spouse | |||

| 2 = Others | |||

| Enabling factors | Education level | 0 = Under elementary school | Under elementary school |

| 1 = Middle & high school | |||

| 2 = Over college | |||

| Household income | 1–5 quantile | 1-quantile | |

| Economic activity | 0 = No | No | |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Insurance type | 0 = Medical aid | Medical aid | |

| 1 = National Health Insurance | |||

| Need factors | Chronic disease | 0 = No | No |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Disability | 0 = No | No | |

| 1 = Yes | |||

2.4. Method of analysis

A frequency analysis was conducted to determine the demographic characteristics of outpatients and inpatients, as well as the overall contents of key variables. Then, to determine the effects of predisposing, enabling, and need factors on health-services-utilization experiences based on the Andersen model, a hierarchical logistic-regression analysis was conducted. The analysis was completed using the statistical package STATA/SE version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

| (1) |

| (2) |

in which = probability of outpatient services; = probability of inpatient services; = predisposing factors (sex, age, marital status); = enabling factors (education level, income level, economic activity, type of insurance); and = need factors (chronic disease, disability).

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics

Table 3 shows the demographic analysis results of the research participants. First, in terms of predisposing factors, there were more women than men in the distribution of participants by year. Moreover, the average age was around 50, indicating that many of them are middle-aged. Most participants were married (around 70%), while 18% of them were single with the rate slightly increasing by year. In terms of enabling factors, middle-school graduates and high-school graduates showed the largest distribution at about 50%. Elementary-school graduates and university graduates or higher also accounted for 25% each, respectively. As for income level, this study used data that equally distributed the values into five categories using the household equivalence scale of the Korea Health Panel data. The distribution slightly varied in the process of eliminating missing values or abnormal values; however, the distribution was relatively even from the first to fifth quantiles. There was a small gap between the economically active (∼55%) and inactive populations (∼45%). Most of the participants had health insurance (95%). Participants who have at least one chronic illness accounted for approximately 65%, taking up a large portion. Approximately 92% of the participants responded that they had no disability.

Table 3.

Demographic analysis.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | Gender | Male | 4,871 (42.9) | 4,812 (43.1) | 4,652 (43.8) |

| Female | 6,491 (57.1) | 6,349 (56.9) | 5,962 (56.2) | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 51.1 (17.8) | 50.6 (18.2) | 50.2 (18.3) | |

| Marital status | Single | 2,010 (17.7) | 2,043 (18.3) | 1,984 (18.7) | |

| Married | 8,002 (70.4) | 7,736 (69.3) | 7,313 (68.9) | ||

| Others | 1,350 (11.2) | 1,382 (12.4) | 1,317 (12.4) | ||

| Enabling factors | Education level | Under elementary | 2,808 (24.7) | 2,793 (25.1) | 2,581 (24.3) |

| Middle & high school | 5,758 (50.7) | 5,617 (50.3) | 5,369 (50.6) | ||

| Over college | 2,796 (24.6) | 2,751 (24.6) | 2,664 (25.1) | ||

| Household income | 1-quantile | 1,634 (14.4) | 1,705 (15.3) | 1,776 (16.7) | |

| 2-quantile | 2,225 (19.6) | 2,140 (19.2) | 2,142 (20.2) | ||

| 3-quantile | 1,391 (21.0) | 2,443 (21.9) | 2,264 (21.3) | ||

| 4-quantile | 2,561 (22.5) | 2,468 (22.1) | 2,208 (20.8) | ||

| 5-quantile | 2,551 (22.5) | 2,405 (21.5) | 2,224 (21.0) | ||

| Economic activity | No | 5,224 (46.0) | 5,183 (46.4) | 4,838 (45.6) | |

| Yes | 6,138 (54.0) | 5,978 (53.6) | 5,776 (54.4) | ||

| Insurance type | Medical aid | 566 (5.0) | 556 (5.0) | 497 (4.7) | |

| National Health Insurance | 10,796 (95.0) | 10,605 (95.0) | 10,117 (95.3) | ||

| Need factors | Chronic disease | No | 4,023 (35.4) | 3,610 (32.3) | 3,473 (32.7) |

| Yes | 7,339 (64.6) | 7,551 (67.7) | 7,141 (67.3) | ||

| Disability | No | 10,613 (93.4) | 10,316 (92.4) | 9,824 (92.6) | |

| Yes | 749 (6.6) | 845 (7.6) | 790 (7.4) | ||

| Total | 11,362 (100.0) | 11,161 (100.0) | 19,614 (100.0) | ||

Data are presented as n (%). SD = standard deviation.

The dependent variable used in this study was the experience of using outpatient and inpatient services. Table 4 shows the distribution of services utilization by the participants in each year. Most of the participants were using outpatient services. By contrast, only ∼14% of the participants were using inpatient services.

Table 4.

Frequency of the dependent variable.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient | No | 23 (0.2) | 19 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) |

| Yes | 11,339 (99.8) | 11,142 (99.8) | 10,603 (99.9) | |

| Inpatient | No | 9,748 (85.8) | 9,588 (85.9) | 9,036 (85.1) |

| Yes | 1,614 (14.2) | 1,573 (14.1) | 1,578 (14.87) |

3.2. Logistic-regression analysis

3.2.1. Health services utilization of outpatient

The results of the hierarchical logistic-regression analysis on outpatient services utilization are shown in Table 5. First, Model 1, including only predisposing factors, showed significant results for sex, age, and marital status. Women tended to use more outpatient services than men did; the older they were, the less they used outpatient services. Married people used 11 times more outpatient services than singles did. Model 2, including both predisposing and enabling factors, showed significance in sex, age, and marital status like Model 1; however, no enabling-factor variable showed significance. Finally, the results of Model 3, including need factors, were as follows. First, the sex, age, and marital status of predisposing factors were significant. However, there was no significant variable among the enabling factors; only the chronic-illness variable showed a significant value among the need factors. Like previous models, women tended to use more outpatient services than men did, and the older they were, the less they used outpatient services. Furthermore, even though the effect size became relatively smaller, married people used eight times more outpatient services than singles did. In addition, those with chronic illness used twice as many outpatient services as those without chronic illness did.

Table 5.

Factors related to health services utilization of outpatients: logistic regression.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | OR | b | SE | OR | b | SE | OR | |||

| Predisposing factors | Gender (male) | Female | 1.17 * | 1.31 | 3.22 | 1.20 * | 1.37 | 3.31 | 1.14 † | 1.33 | 3.12 |

| Age | −0.05 * | 0.01 | 0.95 | −0.05 * | 0.02 | 0.96 | −0.06 * | 0.02 | 0.95 | ||

| Marital (single) | Married | 2.45 † | 7.77 | 11.63 | 2.16 * | 6.09 | 8.69 | 2.12 * | 5.91 | 8.3 | |

| Others | 1.36 | 3.31 | 3.9 | 1.07 | 2.5 | 2.93 | 1 | 2.37 | 2.72 | ||

| Enabling factors | Education level (under elementary) |

Middle & High | −0.3 | 0.37 | 0.74 | −0.32 | 0.38 | 0.73 | |||

| Over college | −0.6 | 0.33 | 0.55 | −0.61 | 0.34 | 0.54 | |||||

| Household income (1-quantile) |

2-quantile | −0.58 | 0.28 | 0.56 | −0.59 | 0.29 | 0.56 | ||||

| 3-quantile | −0.13 | 0.51 | 0.88 | −0.12 | 0.52 | 0.89 | |||||

| 4-quantile | 0.22 | 0.79 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 0.8 | 1.23 | |||||

| 5-quantile | −0.36 | 0.42 | 0.7 | −0.39 | 0.42 | 0.68 | |||||

| Economic activity (no) | Yes | 0.66 | 0.75 | 1.93 | 0.7 | 0.82 | 2.01 | ||||

| Insurance (no) | Yes | 0.56 | 1.06 | 1.76 | 0.48 | 1.03 | 1.62 | ||||

| Need factors | Chronic disease (no) | Yes | 1.03 * | 1.33 | 2.81 | ||||||

| Disability (no) | Yes | −0.83 | 0.23 | 0.44 | |||||||

∗p < 0.1, †p < 0.05.

OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error.

3.2.2. Health services utilization of inpatient

Table 6 shows the results of the hierarchical logistic-regression analysis on inpatient services utilization. Like the results of outpatient services utilization, Model 1 shows the results including only predisposing factors. Age and marital status showed significance for inpatient services utilization; the older they were, the more they used inpatient services. Married people as well as those who experienced separation by either death or divorce used more inpatient services than singles did. Next, in Model 2, adding enabling factors, sex, age, and marital status of predisposing factors were significant. Education level, economic activities, and insurance type, among enabling factors, were significant. Men used more inpatient services than women did, and the older they were, the more they used inpatient services. Furthermore, singles tended to use fewer inpatient services than other groups did. Middle-school, high-school, and university graduates or higher tended to use less inpatient services than elementary-school graduates did. The economically active group used fewer inpatient services than the economically inactive group did; those who paid into health insurance tended to use fewer services than those who received medical reimbursement. Finally, in Model 3, including need factors, the variables significant in Model 2 all showed significant results in the same direction, and chronic illness and disability status also showed significant results. In other words, the group with chronic illness and disability tended to use more inpatient health services.

Table 6.

Factors related to health services utilization of inpatients: logistic regression.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | OR | b | SE | OR | b | SE | OR | |||

| Predisposing factors | Gender (male) | Female | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.99 | −0.13 † | 0.04 | 0.88 | −0.11 † | 0.04 | 0.9 |

| Age | 0.02 ‡ | 0 | 1.02 | 0.01 ‡ | 0 | 1.01 | 0.00 ‡ | 0 | 1.01 | ||

| Marital (single) | Married | 0.17 * | 0.08 | 1.19 | 0.51 ‡ | 0.08 | 1.67 | 0.51 ‡ | 0.08 | 1.67 | |

| Others | 0.29 † | 0.11 | 1.34 | 0.48 ‡ | 0.11 | 1.62 | 0.49 ‡ | 0.11 | 1.62 | ||

| Enabling factors | Education level (under elementary) | Middle & high | −0.32 ‡ | 0.06 | 0.73 | −0.29 ‡ | 0.06 | 0.75 | |||

| Over college | −0.36 ‡ | 0.07 | 0.7 | −0.31 ‡ | 0.07 | 0.73 | |||||

| Household income (1-quantile) | 2-quantile | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.98 | ||||

| 3-quantile | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.99 | |||||

| 4-quantile | −0.1 | 0.07 | 0.91 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.91 | |||||

| 5-quantile | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.98 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.99 | |||||

| Economic activity (no) | Yes | −0.31 ‡ | 0.04 | 0.73 | −0.28 ‡ | 0.04 | 0.75 | ||||

| Insurance (no) | Yes | −0.74 ‡ | 0.08 | 0.48 | −0.63 ‡ | 0.08 | 0.53 | ||||

| Need factors | Chronic disease (no) | Yes | 0.27 ‡ | 0.05 | 1.31 | ||||||

| Disability (no) | Yes | 0.47 ‡ | 0.07 | 1.6 | |||||||

*p < 0.1, †p < 0.05, ‡p < 0.01.

OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the factors affecting health services utilization using logistic-regression analysis by organizing the Korea Health Panel data into panel data (2010–2012). First, experience in health services utilization was more significantly explained by predisposing and need factors than enabling factors. This result was consistent with previous studies reporting that the influence of need factors is stronger than enabling factors in services utilization. There are some limitations in health services utilization by the members of our society due to education level and economic activities, but this indicates that health services are utilized based on health needs 17, 21, 22. Second, when predictors for health-services-utilization experiences of outpatients were examined more specifically, sex, age, and marital status as predisposing factors and chronic illness as a need factor were the variables that had significant effects on health-services-utilization experience. However, enabling factors, such as education level, economic activities, and insurance type, did not have significant effects on health-services-utilization experience. While inequality in services utilization by education did not appear among outpatients, it did appear to be unequal by sex 3, 23. Third, when predictors for health-services-utilization experience of inpatients were examined more specifically, sex, age, and marital status in predisposing factors; education level, economic activities, and insurance type in enabling factors; and chronic illness and disability status in need factors were the significant variables having greater effects on health-services-utilization experience. This result showed that education level and economic activities had relevance in the negative direction, indicating that the higher the income and education level and the more economic activities, hospitalization duration significantly shortened. This may be due to the occurrence of opportunity costs from hospitalization [24].

This study has the following limitations. First, data on health services utilization used in the analysis were not data on expenses. Data on expenses can be analyzed by combining outpatient and inpatient data, and can reflect the intensity of individual treatment and service quality. Second, sociostructural variables, such as income or economic activities, were investigated in detail, but variables related to need factors could not be classified in detail, thereby failing to specifically analyze the need factors that were the most relevant to health services utilization 24, 25. Despite the limitations, this study has significance in that it empirically analyzed the predictors for Korean health services utilization by applying the Andersen model 26, 27. In other words, considering the fact that previous studies applying the Andersen model in Korea were biased to the use of dental and social-welfare services, this study explored and analyzed the predictors by focusing on health services utilization. Furthermore, the fact that this study derived the relative importance of need factors in health services utilization of outpatients and inpatients in Korea also has significance as the possible foundation for providing health services based on needs. Moreover, verifying the general characteristics of outpatients and inpatients by focusing on their health services utilization provides the baseline data for establishing health service policies and programs with regard to the recently increasing interest in health services 28, 29, 30.

Based on the research findings, this study suggests the practical implications for providing health services for outpatients and inpatients. First, it is important to assess the needs in the process of providing services for outpatients and inpatients who visit the medical institution. This study proved that the need factors of inpatients were powerful factors explaining health services utilization [29]. It is necessary to consider this fact and pay close attention to how the level of need changes in the actual field. Second, it is necessary to consider the general characteristics when developing health service policies and programs for outpatients and inpatients, and providing services in the field. The level of health services utilization may vary based on education level; thus, it is necessary to ensure that information on services utilization or procedures can be obtained easily and sufficiently. Furthermore, social discrimination or stigma may be greater, depending on chronic illness or disability 31, 32; thus, there must be careful interventions so that the patients do not receive limited services due to frustration or intimidation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Phillips K.A., Morrison K.R., Andersen R., Aday L.A. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998 Aug;33(3):571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glanz K., Lewis F.M., Rimer B.K. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1990. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padgett D., Struening E.L., Andrews H. Factors affecting the use of medical, mental health, alcohol, and drug treatment services by homeless adults. Med Care. 1990 Sep;28(9):805–821. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aday L.A., Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen R., Smedby B., Anderson O.W. Center for Health Administration Studies; 1970. Medical care use in Sweden and the United States: a comparative analysis of systems and behavior; pp. 34–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurd M.D., McGarry K. Medical insurance and the use of health care services by the elderly. J Health Econ. 1997 Apr;16(2):129–154. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen R., Lewis S.Z., Giachello A.L., Aday L.A., Chiu G. Access to medical care among the Hispanic population of the southwestern United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1981 Mar;22(1):78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelberg L., Andersen R.M., Leake B.D. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000 Feb;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendenhall A.N. Predictors of service utilization among youth diagnosed with mood disorders. J Child Family Stud. 2012 Aug;21(4):603–611. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindamer L.A., Liu L., Sommerfeld D.H. Predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with high service use in a public mental health system. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012 May;39(3):200–209. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0350-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diehr P., Yanez D., Ash A., Hornbrook M., Lin D. Methods for analyzing health care utilization and costs. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20(1):125–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett B., Young M.S. Past-year acute behavioral health care utilization among individuals with mental health disorders: results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. J Dual Diagn. 2012;8(1):19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen R., Newman J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005 Dec;83(4):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein J.A., Andersen R., Gelberg L. Applying the Gelberg–Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. J Health Psychol. 2007 Sep;12(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein J.A., Andersen R.M., Robertson M., Gelberg L. Impact of hepatitis B and C infection on health services utilization in homeless adults: a test of the Gelberg–Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations. Health Psychol. 2012 Jan;31(1):20–30. doi: 10.1037/a0023643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schomerus G., Appel K., Meffert P.J. Personality-related factors as predictors of help-seeking for depression: a population-based study applying the behavioral model of health services use. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013 Nov;48(11):1809–1817. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0643-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen R.M., Davidson P., Ganz P. Symbiotic relationships of quality of life, health services research and other health research. Qual Life Res. 1994 Oct;3(5):365–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00451728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman J.F., Jr. Emory University; 1971. The utilization of dental services; pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter F., Webster A., Scott S., Emery J. The Andersen model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012 Apr;17(2):110–118. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Doorslaer E., Wagstaff A., Van der Burg H. Equity in the delivery of health care in Europe and the US. J Health Econ. 2000 Sep;19(5):553–583. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H., Lee T., Jeon B., Jung Y. Factors related to health care utilization in the poor and the general populations. Korean J Health Econ Policy. 2009;15(1):79–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen R., Kravits J., Anderson O.W. The public's view of the crisis in medical care: an impetus for changing delivery systems? Econ Business Bull. 1971;24(1):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995 Mar;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasl S.V., Cobb S. Health behavior, illness behavior and sick role behavior: I. Health and illness behavior. Arch Environ Health. 1966 Feb;12(2):246–266. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1966.10664365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold M. A crisis of identity: the case of medical sociology. J Health Soc Behav. 1977 Jun;18(2):160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemming M.R., Calsyn R.J. Ability of the behavioral model to predict utilization of five services by individuals suffering from severe mental illness and homelessness. J Soc Serv Res. 2006;32(3):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afifi A.A., Kotlerman J.B., Ettner S.L., Cowan M. Methods for improving regression analysis for skewed continuous or counted responses. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007 Apr;28:95–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.082206.094100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker M.H., Maiman L.A. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975 Jan;13(1):10–24. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenstock I.M., Strecher V.J., Becker M.H. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988 Jun;15(2):175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith G.H., III, Scheid T.L. Vol. 31. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.; England: 2014. An Application of the Andersen Model of Health Utilization to the Understanding of the Role of Race-Concordant Doctor–Patient Relationships in Reducing Health Disparities; pp. 187–214. (Social Determinants, Health Disparities and Linkages to Health and Health Care (Research in the Sociology of Health Care, Volume 31)). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lachenbruch P.A. Analysis of data with excess zeros. Stat Methods Med Res. 2002 Aug;11(4):297–302. doi: 10.1191/0962280202sm289ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babitsch B., Gohl D., von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen's behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012 Oct;9:1–15. doi: 10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]