Abstract

Objective

Late HIV testing (LT) defined as an AIDS diagnosis within a year of first positive HIV test is associated with higher HIV transmission, lower HAART effectiveness, and worse outcomes. Latinos represent 36% of LT in the US, yet research concerning LT among HIV cases in Puerto Rico is scarce.

Methods

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with LT and Cochran-Armitage test to describe LT trends in an HIV infected cohort followed at a specialized HIV clinic in Puerto Rico.

Results

From 2000 to 2011, 47% of eligible patients were LT, with lower median CD4 count (54 vs. 420 cells/mm3) and higher median HIV viral load counts (253,680 vs. 23,700 copies/mL), when compared to non-LT patients. LT prevalence decreased significantly, from 47% in 2000 to 37% in 2011. In a mutually adjusted logistic regression model, males, older age at enrolment and past history of IDU significantly increased LT odds whereas history of amphetamine use decreased LT odds. Stratified by mode of transmission, only men who have sex with men (MSM), had a significant reduction in the proportion of LT, from 67% in 2000 to 33% in 2011.

Conclusion

These results suggest a gap in early HIV detection in Puerto Rico that decreased only among MSM. A closer evaluation of HIV testing guideline implementation among non MSM in the Island is needed.

Indexing terms: Late HIV, Puerto Rico HIV, AIDS diagnosis, late testing, HIV trends

INTRODUCTION

In 2009, an estimated 32% of persons diagnosed with HIV in the United States (US) were diagnosed with AIDS within 1 year of initial diagnosis (1), a phenomenon referred to as late testing (LT). Patients with LT have delayed initiation of HIV treatment and are prone to more complicated treatment, worse overall prognosis (2), diminished recovery of CD4 T-lymphocytes (3) and higher mortality even after receipt of antiretroviral therapy (4). Lack of infection awareness may prolong opportunities to transmit HIV and substantially increase medical costs (5).

Although US Latinos represent 20% of all new HIV infections, they account for 36% of late testers (1). The heterogeneity of the “Latino” classification complicates addressing this disparity given that it comprises people from over 20 countries (6), with differing risk factors, behaviors, and rates of infections. For example, the injection drug use (IDU) transmission pathway- a significant risk factor for LT – accounts for 25% of HIV infections diagnosed among Puerto Ricans but only 6% among Mexicans (1). Also, the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infections in Puerto Rico, estimated at 36%, is twice that of the US (7). Puerto Ricans are the second largest Hispanic/Latino group in the US (8). There are an estimated 4.9 million Puerto Ricans living on the mainland and 3.7 million living on the island, all of whom are free to migrate to and from the US (8). Therefore, LT among HIV infected persons on the island may be relevant to the epidemiology of Puerto Ricans on the mainland.

However, data concerning LT among HIV-infected persons in Puerto Rico are scarce. Review of the scientific literature identified no publications that examined the epidemiology of LT among HIV-infected individuals living in Puerto Rico. Determining the prevalence of and factors associated with LT should inform efforts to decrease this important public health problem by providing data to design programs targeting those identified at greatest risk. The main objective of this study was to determine factors associated with LT and describe trends in a cohort of HIV-infected individuals who entered HIV care in Puerto Rico between 2000 and 2011.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were obtained from baseline questionnaires of the Retroviral Research Center (RRC) longitudinal cohort study of confirmed HIV-infected patients followed for care at the Ramón Ruíz Arnaú University Hospital (inpatient or ambulatory clinics) in Bayamón, Puerto Rico. Invited participants were HIV-infected adults 18 years of age or older followed for HIV care at the RRC and its clinics. After consent was obtained, a baseline questionnaire was administered and baseline laboratory tests were performed. The baseline questionnaire included 12-months of retrospective medical history supplemented with hospital and medical record abstraction (9). Participants were then interviewed in 6 months intervals thereafter and compensated $10 towards their transportation expenses. An institutional review board of the Universidad Central del Caribe approved the study. More detailed inclusion criteria into the general cohort study, patient consent and IRB approval have been published elsewhere (9, 10).

The RRC is the only center that has followed an open cohort of HIV/AIDS patients presenting for care in the Bayamón area since 1992 (11) and it is the only large HIV cohort on the island. RRC collects information on patient factors via a registry organized into various categories, including socio-demographics; risk-related practices; psychosocial, clinical and immunological modules; and standard surveillance information (e.g., mode of transmission, CD4 and viral load count). The Bayamón area is one of eight health care regions in PR (12), representing 16% of the island population and the second highest HIV/AIDS prevalence (13).

We defined LT per the CDC definition as an AIDS diagnosis within one year of initial positive reported HIV test (14). Given that some of the factors associated with LT might also be associated with delayed entry into HIV care, the study sample was further restricted to include only those late testers with timely entry defined as joining the study cohort within one year of initial positive reported HIV test. This restriction was done to minimize potential confounding by care delays and to decrease opportunities for LT misclassification (15). The one year time span to define timely entry is within the range of other published studies (16). AIDS in the cohort study was defined per the 1993 CDC AIDS definition (17), which includes immunological (CD4 count <200 cells/mm3) and/or clinical (the presence of an AIDS-defining condition) diagnoses. HIV and AIDS diagnoses dates were abstracted from medical records. All cohort participants with an available date of entry into the study and a first reported HIV test date were included in our analysis.

Demographics, illicit drug use, lifestyle and clinical characteristics extracted from the modular questionnaires were described by gender and LT status. Mode of transmission included heterosexual, men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug use (IDU). Lifestyle covariates and drug use were collected as “ever use” (yes/no), with the exception of a variable asking patients reporting a history of IDU if they had injected the year before study enrollment. Using this information, a trichotomous variable was created to categorize “non-IDU”, “recent IDU” if they injected in the year prior to study entry or “remote IDU” if they reported IDU but not in the year prior to study enrollment.

The Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare differences in the distribution of categorical variables by LT. The Student t-test was used to compare means for normally distributed continuous variables by LT status and the Wilcoxon rank-sum was used to test the difference between medians for non-normally distributed continuous variables by LT status. Statistically significant associations (two sided alpha of <0.05) for LT in the bivariate analysis were entered simultaneously into a multivariable logistic regression model. Effect modification by gender and IDU level (recent versus remote) was examined based on observed differences in risk factors for LT among males and IDU in bivariate analysis. Crude odds ratios (OR) or adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Cumulative AIDS prevalence was calculated as the proportion of total AIDS diagnoses among the sample of HIV-infected patients. Changes in LT trends over time were measured with Cochran-Armitage test and stratified by gender and mode of transmission categories. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

RRC Cohort Patients

From 2000 to 2011, a total of 1582 patients entered the cohort as patients. The median age was 40 years (range 18 to 79 years). Most patients were men (66%, including 29% MSM), nearly one third did not complete the 10th grade of education (31%) and over one third of these study participants had ever been imprisoned (35%). The most common modes of transmission were heterosexual (50%) and IDU (33%, including the MSM/IDU category). Most of the study participants (99%) reported illicit drug use. Cocaine was reported as the most commonly used drug (53%), including 26% reporting crack use. Over a third of the study participants had injected drugs at some point in their lifetime (35%), most of these were recent injectors (60%). The proportion reporting IDU was higher among men (42%) than women (20%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected patients with timely entry to care in the RRC cohort from 2000–2011 by LT status

| Overall N=1582 |

Timely entry* (n=795) (%) |

Not timely entry (n=787) | p-Value | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n=1582) | 0.03 | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.98) | |||

| Male | 1051 (66%) | 508 (64) | 543 (69) | ||

| Female | 531 (34%) | 287 (36) | 244 (31) | ||

|

| |||||

| Age in years (n=1582) | 0.06 | ||||

| <30 | 224 (14) | 124 (16) | 100 (13) | REF | |

| 30–44 | 845 (53) | 402 (50) | 443 (56) | 0.60 (0.44 to 0.82) | |

| ≥45 | 513 (32) | 269 (34) | 244 (31) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | |

|

| |||||

| Education (n=1569) | 0.28 | ||||

| ≤9th grade | 485 (31) | 236 (30) | 249 (32) | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.09) | |

| 10–12th grade | 612 (39) | 299 (38) | 313 (40) | 0.86 (0.67 to 1.10) | |

| >12th grade | 472 (30) | 251 (32) | 221 (28) | REF | |

|

| |||||

| Lifestyle Profile (lifetime) | |||||

| Smoking (n=1576) | 1134 (72) | 522 (66) | 612 (78) | <0.01 | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.68) |

| Alcohol use (n=1575) | 811 (51) | 417 (53) | 394 (50) | 0.33 | 1.1 (0.91 to 1.34) |

| Stay in prison (n=1570) | 547 (35) | 178 (23) | 369 (47) | <0.01 | 0.33 (0.26 to 0.41) |

|

| |||||

| CDC Mode of transmission (n=1495) | <0.01 | ||||

| IDU | 447 (30) | 139 (18) | 308 (42) | 0.28 (0.22 to 0.36) | |

| IDU/MSM | 38 (2.5) | 6 (1) | 32 (4) | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.29) | |

| MSM | 262(17.5) | 151 (20) | 111 (15) | 0.87 (0.65 to 1.15) | |

| Hetero | 748 (50) | 458 (61) | 290 (39) | REF | |

|

| |||||

| Drug Use Prevalence ever | |||||

| Cocaine and crack (n=1578) | 833 (53) | 323 (41) | 510 (65) | <0.01 | 0.37 (0.30 to 0.45) |

| Cannabinoid (n=1575) | 729 (46) | 305 (38) | 424 (54) | <0.01 | 0.53 (0.43 to 0.64) |

| Heroin (n=1577) | 590 (37) | 200 (25) | 390 (50) | <0.01 | 0.34 (0.28 to 0.42) |

| Speedball (n=1572) | 517 (33) | 166 (21) | 351 (45) | <0.01 | 0.33 (0.26 to 0.41) |

| Amphetamine (n=1570) | 369 (24) | 130 (16) | 239 (31) | <0.01 | 0.45 (0.35 to 0.57) |

| Ecstasy (n=1120) | 42 (4) | 18 (3) | 24 (4) | 0.32 | 0.73 (0.39 to 1.36) |

| IDU (n=1575) | <0.01 | ||||

| Remote IDU | 200 (13) | 56 (7) | 144 (18) | 0.24 (0.17 to 0.34) | |

| Recent IDU | 344 (22) | 113 (14) | 231 (30) | 0.30 (0.23 to 0.39) | |

| Non-IDU | 1031 (65) | 623 (79) | 408 (52) | REF | |

Timely entry = entered cohort within 1 year of first reported HIV test

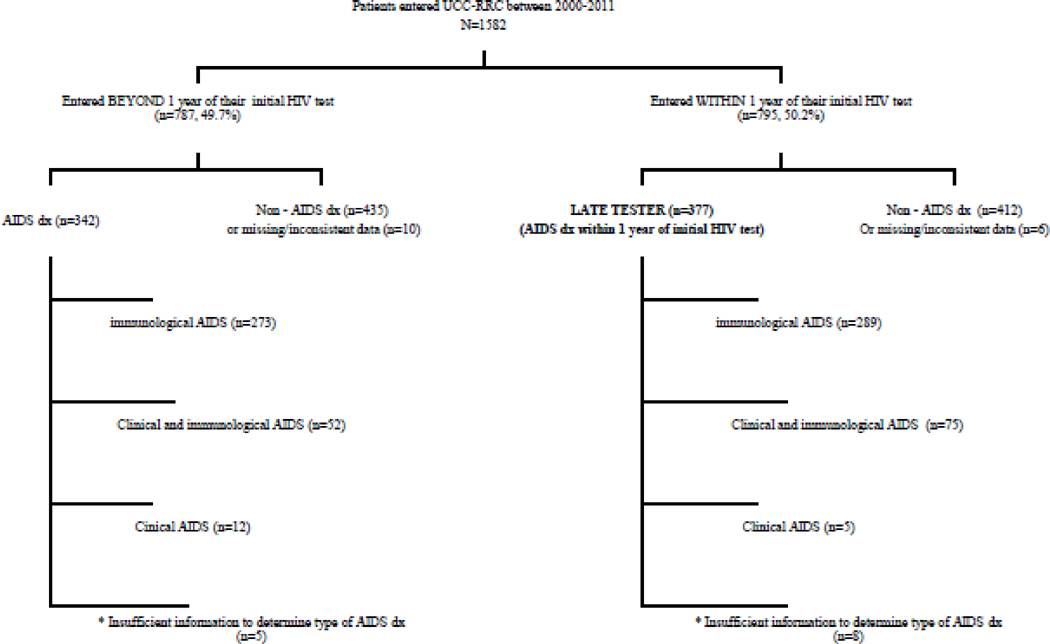

Overall, 45% (n=719) of the cohort were diagnosed with AIDS at enrollment. Seventy eight percent had immunologic AIDS (n=562), 18% (n=127) had both clinical and immunologic AIDS and approximately 2% (n=17) had clinical AIDS alone (Figure 1). The median number of days from first reported positive HIV test to entry into the study was 353 (Inter Quartile Range [IQR] = 64 – 2615 days). The median CD4 count and HIV viral loads were 253 cells/mm3 (IQR=80 – 470 cells/mm3), and 38,200 copies/mL (IQR=2,950 – 204,000 copies/mL), respectively. Thirty five percent (n=546) of study participants had an HIV viral load > 100,000 copies/mL. The median CD4 and viral load counts did not differ significantly by gender (p=0.07 and p=0.19 respectively).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing distribution of AIDS diagnoses for patients who entered the cohort within one year of first reported HIV test versus those entering beyond one year of their first reported HIV test. * = Missing data on viral load or CD4 recorded data of AIDS diagnosed.

Analytic Sample

Among those who entered the study within one year of their first reported positive HIV test (n=795) (timely entry), the median number of days from the HIV test to entry into the cohort, was 64 (IQR= 43–96). The median CD4 count and HIV viral load were 216 cells/mm3 (IQR=57 – 433 cells/mm3) and 73,670 copies/mL (IQR=12,200 – 346,750 copies/mL) respectively. They were less likely to be males, smokers or drug users and less likely to report a history of incarceration. The proportion of patients who reported IDU as their mode of transmission was 19% compared to 33% for the entire study participants (Table 1).

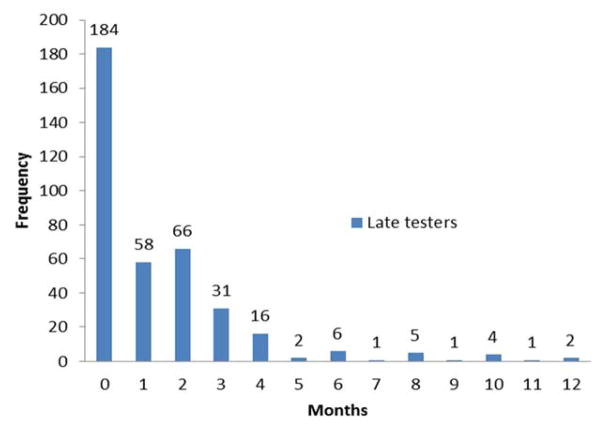

Nearly half (47%, n=377) of those with timely entry had a recorded AIDS diagnosis and were classified as LT. Ninety percent (n=339) of LT had an AIDS diagnosis within the first three months after their first reported positive HIV test, including 49% (n=184) who were concurrently diagnosed with HIV and AIDS at entry (Figure 2). Most AIDS diagnoses were immunological (77%, n=289) (Figure 1). The median CD4 count and viral load counts among the LT group were 54 cells/mm3 (IQR=21–116 cells/mm3) and 253,680 copies/mL (IQR=73,670–684,000 copies/mL) respectively, compared to 420 cells/mm3 (IQR=295–596 cells/mm3) and 23,700 copies/mL (IQR=4190–82120 copies/mL) for non-late testers. Among LT, the CD4 count was similar for males versus females. However, the median viral load was significantly lower in males (209,630; IQR = 67,400 – 594,000) than females (404,875 copies/mL; IQR=97,100 – 750,000) (p=0.02).

Figure 2.

Distribution of time to AIDS diagnosis (in months) among 377 late testers (LT).

Factors associated with late testing

Factors independently associated with increased odds of LT included male gender, older age, and IDU (Table 2). History of imprisonment and history of amphetamine use decreased the odds of LT. Factors remaining significantly associated with LT in the multivariable logistic model were male gender (AOR=1.59, 95%CI=1.15 to 2.17), older age (30–44 years AOR=1.68, 95%CI=1.09 to 2.62 and ≥45 years AOR=3.31, 95%CI=2.08 to 5.27); remote IDU (AOR=2.42, 95%CI=1.24 to 4.69) and history of amphetamine use (AOR=0.52, CI: 0.31 to 0.87).

Table 2.

Characteristics of HIV patients entering care at the UCC-RCC from 2000 to 2011, by Late testing status:

| Timely entry* n=795 (%) |

Late (AIDS dx) n=377 (%) |

Not Late (no AIDS dx) n=418 (%) |

p-Value | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender n=795 | 0.04 | ||||

| Males | 508 (64) | 255 (68) | 253 (61) | 1.36 (1.02 to 1.82) | |

| Female | 287 (36) | 122 (32) | 165 (39) | REF | |

|

| |||||

| Age (n=795) | <0.01 | ||||

| <30 | 124 (16) | 40 (11) | 84 (20) | REF | |

| 30–44 | 402 (50) | 174 (46) | 228 (54) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | |

| ≥45 | 269 (34) | 163 (43) | 106 (25) | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.3) | |

|

| |||||

| Education (n=786) | 0.16 | ||||

| ≤9th grade | 236 (30) | 124 (33) | 112 (27) | 1.4 (0.98 to 1.99) | |

| 10–12th grade | 299 (38) | 136 (37) | 163 (39) | 1.1 (0.75 to 1.46) | |

| >12th grade | 251 (32) | 112 (30) | 139 (34) | REF | |

|

| |||||

| Lifestyle Profile (ever) | |||||

| Smoking (n=792) | 522 (66) | 244 (65) | 278 (67) | 0.64 | 0.93 (0.69 to 1.25) |

| Alcohol use (n=791) | 417 (53) | 208 (55) | 209 (50) | 0.14 | 1.23 (0.93 to 1.63) |

| Stay in prison (n=788) | 178 (23) | 71 (19) | 107 (26) | 0.02 | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.95) |

|

| |||||

| CDC Mode of transmission (n=795) | 0.43 | ||||

| IDU | 139 (18) | 61 (17) | 78 (20) | 0.80 (0.54 to 1.17) | |

| IDU/MSM | 6 (1) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1) | 0.51 (0.09 to 2.81) | |

| MSM | 151 (20) | 67 (19) | 84 (21) | 0.81 (0.56 to 1.18) | |

| Hetero | 458 (61) | 228 (64) | 230 (58) | REF | |

|

| |||||

| Drug Prevalence | |||||

| Cocaine and crack (n=794) | 323 (41) | 147 (39) | 176 (42) | 0.36 | 0.88 (0.66 to 1.16) |

| Cannabinoid (n=794) | 305 (38) | 133 (35) | 172 (41) | 0.08 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.04) |

| Heroin (n=793) | 200 (25) | 86 (23) | 114 (27) | 0.15 | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.1) |

| Speedball (n=789) | 166 (21) | 68 (18) | 98 (24) | 0.06 | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.02) |

| Amphetamine (n=790) | 130 (16) | 44 (12) | 86 (21) | <0.01 | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.75) |

| Ecstasy (n=565) | 18 (3) | 5 (2) | 13 (4) | 0.10 | 0.42 (0.15 to 1.21) |

| IDU (n=792) | <0.01 | ||||

| Remote IDU | 56 (7) | 34 (9) | 22 (5) | 1.62 (0.93 to 2.84) | |

| Recent IDU | 113 (14) | 38 (10) | 75 (18) | 0.53 (0.34 to 0.81) | |

| Non-IDU | 623 (79) | 304 (81) | 319 (77) | REF | |

Timely entry = entered cohort within 1 year of first reported HIV test

Trends in Late Testing over time

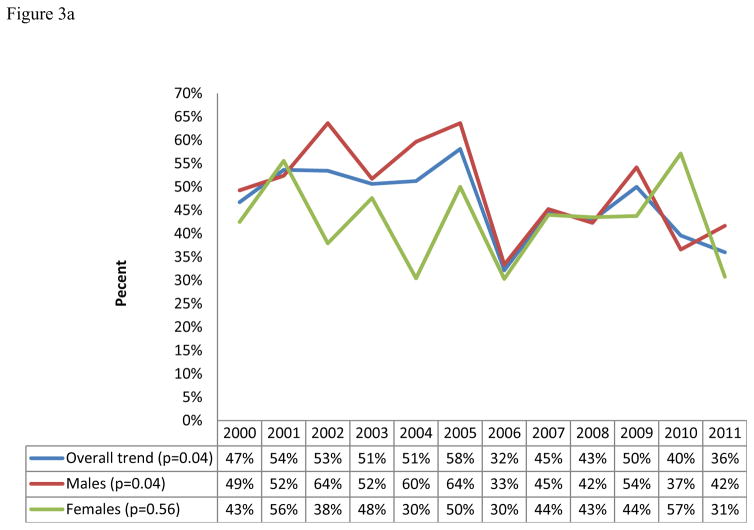

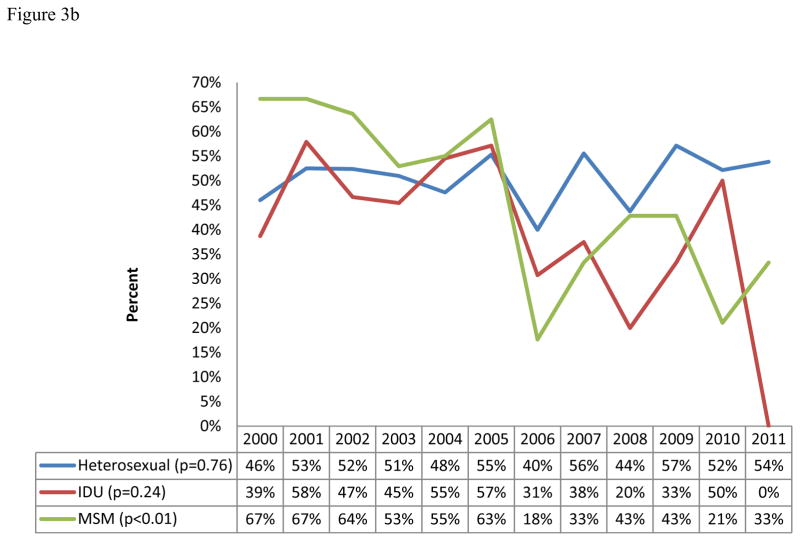

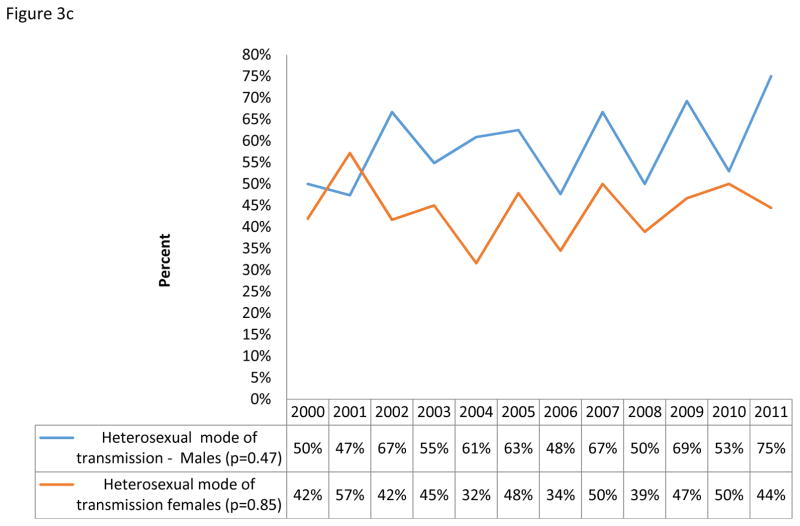

Yearly LT prevalence ranged from a high of 58% to a low of 32%. Overall, LT prevalence showed a significantly decreasing yearly trend during the study period (from 47% in 2000 to 36% in 2011, p= 0.04, n=795, Figure 3a). Stratified by gender and mode of transmission, only those reporting MSM as their mode of transmission showed a statistically significant decrease in prevalence of LT from 67% in 2000 to 33% in 2011 (p<0.01, n=151, Figures 3a and b). A non-statistically significant increasing yearly trend of LT prevalence was observed for heterosexual transmission among males (46% to 54%, p = 0.72, n = 255, figures 3c).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a: Yearly trends of LT overall and by gender

Figure 3b: Yearly trends of LT by mode of transmission

Figure 3c: Yearly trends of LT for heterosexual mode of transmission by gender

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to describe risk factors for LT among HIV-infected patients on the island of Puerto Rico. Male gender, older age, remote histories of IDU and amphetamine use were associated with LT in this cohort. Nearly half of the patients studied presented to care late, substantially higher than the US (32%), suggesting that LT should be a priority issue for interventions in this population.

Our finding that men are more likely to have LT is consistent with studies reported in Venezuela, France, England, Italy and the US (18–24) and is consistent with findings that males tend to have lower utilization rates of health services (23, 25). In addition, since males do not participate in antenatal care, they may have fewer opportunities for HIV screening than females (23, 25). Our finding that older age is a risk factor for LT is consistent with studies showing that older patients and their physicians may lack risk awareness which could lead to progression of HIV prior to its recognition (26, 27).

Injection drug users often have decreased access to care, social stigma, and fear of legal repercussions which may contribute to an increased likelihood of LT and delayed HIV care presentation (16, 28–30). Our study is unique because it categorized IDU as recent versus remote behavior whereas many other studies describe IDU as “ever injected” or “never injected” (16, 28, 31, 32). In multivariable analysis only remote injection history was independently associated with increased odds of LT when compared to non-injectors. Remote injectors might interact with healthcare less often than recent injectors because recent injectors may suffer from health complications of their actions (33–35). Less healthcare interactions could lead to fewer opportunities for testing.

Although the association of amphetamine use with a decreased risk of late testing may seem counterintuitive, one suggested explanation for this finding may be the documented frequency of access to care by amphetamine users (36). Amphetamine users are at increased likelihood of health complications that increase their interactions with the health care system; for example, dermatological disorders, depression and violence (37–43). Any of these interactions could stimulate an HIV test. The CDC has documented increases in methamphetamine-related deaths, emergency visits and persons seeking treatment (44). In an area of high HIV prevalence and substance abuse such as Bayamón, frequent interactions with health care facilities could provide opportunities to receive an HIV test (43, 44). While history of incarceration did not remain significant in multivariable analysis, its association with decreased odds of LT during the bivariate analysis may be related to increased opportunities for HIV education, and testing while in prison (45).

There was a substantial decline over 11 years in LT among males. This trend was driven primarily by the MSM population. The 2006 implementation of routine opt-out HIV testing (46) may have increased HIV testing rates in some sub-populations; such as males relative to females because many females may have already been tested at antenatal clinics (47, 48).

This study had several limitations. These results are from a cohort at a single facility and may not be generalizable to the entire HIV-infected population of the island. However, the distribution of age and mode of transmission in this cohort are similar to the island’s HIV surveillance data (48). In addition, there may be misclassification of first reported HIV test if any patients had HIV testing before the date identified through the cohort interview and medical record abstraction. A method to further validate these dates was not available to the RRC. This study may also be subject to prevalence-incidence bias which might have exaggerated the relationship between age and LT.

This study demonstrates that LT is an important public health problem in the study cohort. Further studies are needed to examine the prevalence of LT overall and by region. Such a study might be performed using HIV/AIDS public health surveillance data. Given that factors associated with LT such as older age and IDU are highly prevalent among HIV-infected Puerto Ricans, interventions to reduce LT will need to address issues relevant to these subpopulations. Qualitative and quantitative assessments to understand underlying reasons for LT within these subgroups are needed. Finally an assessment of the adoption of opt-out HIV screening practices on the island may also be helpful to quantify the issue of missed opportunities. Given the disproportionate representation of Puerto Ricans in the US HIV epidemic, efforts to reduce LT in this population may have a significant impact on the epidemiology of HIV in the US.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the patients who participated in this research. We are in debt to the research team at the Universidad Central de Caribe, Retroviral Research Center and DMSRSU from RCMI-UCC for generously sharing their valuable data with us. We also thank Dr. Supriya Mehta, Dr. Ronald C. Hershow and Dr. Robert Bailey for their invaluable assistance in editing this manuscript.

Funding Sources Statement: The original cohort study is funded by NIH grant number 8U54MD007587 and 8G12MD007583 from the NIMHD.

Footnotes

Publishable Disclosure Statement of Potential Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Katherine Y. Tossas-Milligan, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, 1603 W. Taylor Street, M/C 923, Chicago, IL 60612, USA.

Robert F. Hunter-Mellado, Retrovirus Research Center, Internal Medicine Department, Universidad Central del Caribe, School of Medicine, Bayamón, Puerto Rico.

Angel M. Mayor, Retrovirus Research Center, Internal Medicine Department, Universidad Central del Caribe, School of Medicine, Bayamón, Puerto Rico.

Diana M. Fernandez-Santos, Retrovirus Research Center, Internal Medicine Department, Universidad Central del Caribe, School of Medicine, Bayamón, Puerto Rico.

Mark S. Dworkin, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, 1603 W. Taylor Street, M/C 923, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

References

- 1.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2010. 2012 Mar;22 Available at : http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_report_vol_22.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lain MA, Valverde M, Frehill LM. Late entry into HIV/AIDS medical care: the importance of past relationships with medical providers. AIDS Care. 2007;19:190–194. doi: 10.1080/09540120600970903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins GK, Spritzler JG, Chan ES, et al. Incomplete reconstitution of T cell subsets on combination antiretroviral therapy in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 384. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:350–361. doi: 10.1086/595888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smit C, Hallett TB, Lange J, Garnett G, de Wolf F. Late entry to HIV care limits the impact of anti-retroviral therapy in The Netherlands. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Network HR. The economic burden of late entry into medical care for patients with HIV infection. Med Care. 2010;48:1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humes K, Jones N, Ramirez R, editors. 2010 Census Brief. 2010 Mar, 2010. Census Bot. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérez CM, Marrero E, Meléndez M, et al. Seroepidemiology of viral hepatitis, HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in the household population aged 21–64 years in Puerto Rico. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown A, Patten E. Hispanics of Puerto Rican Origin in the United States. Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Accessed November 1, 2014]. Available at http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/06/PuertoRicanFactsheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gómez MA, Velázquez M, Hunter RF. Outline of the Human Retrovirus Registry: profile of a Puerto Rican HIV infected population. Bol Asoc Med P R 1997. 1997;89:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farizo KM, Buehler JW, Chamberland ME, et al. Spectrum of disease in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States. JAMA. 1992;267:1798–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Báez-Feliciano DV, Quintana R, Gómez MA, et al. Trends in the HIV and AIDS epidemic in a Puerto Rican cohort of patients: 1992–2005. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2006;98:174–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bureau USC. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 130. Washington, D.C: U.S Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Action A. State Facts - HIV/AIDS In Puerto Rico. Washington, D.C: AIDS Action; 2005. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.HIV Testing and Diagnosis Among Adults - United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2010;59:1550–1555. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5947a3.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarcz SK, Hsu L, Chin CSJ, Richards TA, Frank H, Wenzel C, Dilley J. Do people who develop AIDS within 12 months of HIV diagnosis delay HIV testing? Public Health Reports. 2011;126:552. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girardi E, Aloisi MS, Arici C, et al. Delayed presentation and late testing for HIV: demographic and behavioral risk factors in a multicenter study in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:951–959. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. Recomm Rep. 1992;41:1–19. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonjour MA, Montagne M, Zambrano M, et al. Determinants of late disease-stage presentation at diagnosis of HIV infection in Venezuela: a case-case comparison. AIDS Res Ther. 2008;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couturier E, Schwoebel V, Michon C, et al. Determinants of delayed diagnosis of HIV infection in France, 1993–1995. AIDS. 1998;12:795–800. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mugavero MJ, Castellano C, Edelman D, Hicks C. Late diagnosis of HIV infection: the role of age and sex. Am J Med. 2007;120:370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadborn TR, Baster K, Delpech VC, et al. No time to wait: how many HIV-infected homosexual men are diagnosed late and consequently die? (England and Wales, 1993–2002) AIDS. 2005;19:513–520. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162340.43310.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castilla J, Sobrino P, De La Fuente L, Noguer I, Guerra L, Parras F. Late diagnosis of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: consequences for AIDS incidence. AIDS. 2002;16:1945–1951. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nacher M, El Guedj M, Vaz T, et al. Risk factors for late HIV diagnosis in French Guiana. AIDS. 2005;19:727–729. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166096.69811.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, Sinka K, Evans BG. The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000–2004) AIDS. 2006;20:2371–2379. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brookmeyer R. Reconstruction and future trends of the AIDS epidemic in the United States. Science. 1991;253:37–42. doi: 10.1126/science.2063206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skiest DJ, Keiser P. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in patients older than 50 years. A survey of primary care physicians’ beliefs, practices, and knowledge. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2008;3:453. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grigoryan A, Hall HI, Durant T, Wei X. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US States, 1996–2004. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adih WK, Campsmith M, Williams CL, Hardnett FP, Hughes D. Epidemiology of HIV among Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States, 2001–2008. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10:150–159. doi: 10.1177/1545109711399805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wand H, Guy R, Law M, Wilson D, Maher L. High Rates of Late HIV Diagnosis Among People Who Inject Drugs Compared to Men Who Have Sex with Men and Heterosexual Men and Women in Australia. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wohl AR, Tejero J, Frye DM. Factors associated with late HIV testing for Latinos diagnosed with AIDS in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1203–1210. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ndiaye B, Salleron J, Vincent A, et al. Factors associated with presentation to care with advanced HIV disease in Brussels and Northern France: 1997–2007. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Galai N, Doherty MC, Nelson KE. Viral infections in short-term injection drug users: the prevalence of the hepatitis C, hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency, and human T-lymphotropic viruses. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:655–661. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kral AH, Lorvick J, Edlin BR. Sex- and drug-related risk among populations of younger and older injection drug users in adjacent neighborhoods in San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:162–167. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seal KH, Kral AH, Gee L, et al. Predictors and prevention of nonfatal overdose among street-recruited injection heroin users in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1998–1999. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1842–1846. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards JR, Bretz SW, Johnson EB, Turnipseed SD, Brofeldt BT, Derlet RW. Methamphetamine abuse and emergency department utilization. West J Med. 1999;170:198–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mooney LJ, Glasner-Edwards S, Rawson RA, Ling W. Medical effects of methamphetamine use. In: Roll JM, Rawson RA, Ling W, Shoptaw S, editors. Methamphetamine Addiction: From Basic Science to Treatment. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darke S, Torok M, Kaye S, Duflou J. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and symptoms among regular psychostimulant users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:371–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo KK, Wijetunga M, Ito H, et al. The association of methamphetamine use and cardiomyopathy in young patients. Am J Med. 2007;120:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998;168:93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darke S, Ross J, Cohen J, Hando J, Hall W. Injecting and sexual risk-taking behaviour among regular amphetamine users. AIDS Care. 1995;7:19–26. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalmau A, Bergman B, Brismar B. Psychotic disorders among inpatients with abuse of cannabis, amphetamine and opiates. Do dopaminergic stimulants facilitate psychiatric illness? Eur Psychiatry. 1999;14:366–371. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT, Burchett B, Blazer DG, Woody GE, Ling W. Co-occurring amphetamine use and associated medical and psychiatric comorbidity among opioid-dependent adults: results from the Clinical Trials Network. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011;2:133–144. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S20895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drug Abuse Warning Network. Emergency department visits involving methamphetamine: 2004–2008. Washington DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP. Enrollment in Outpatient Care Among Newly Released Prison Inmates with HIV Infection. Public health reports. 2010;125:64–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100:131–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zetola NM, Grijalva CG, Gertler S, et al. Simplifying consent for HIV testing is associated with an increase in HIV testing and case detection in highest risk groups, San Francisco January 2003-June 2007. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program. Office of Epidemiology and Research, Puerto Rico Health Department eHARS System; Jun 29, 2012. [Accessed October, 21, 2012]. Puerto Rico HIV/AIDS Surveillance Summary Cumulative HIV/AIDS Cases Diagnosed as of June 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.salud.gov.pr/unidadesdeapoyo/Estdisticas%20Generales/Puerto%20Rico%20HIV%20AIDS%20Surveillance%20Summary%20junio%202012.pdf. [Google Scholar]