Abstract

Characteristics, HIV risk, and program coverage for underage female sex workers (FSW) are rarely systematically described worldwide. We compared characteristics of underage (15–17 years old) and adult (≥18 years old) FSW in three main urban areas of Mozambique (Maputo, Beira and Nampula) using data from three respondent-driven sampling surveys implemented in 2011–2012. Among survey participants, 9.8 % (39/400) in Maputo, 17.0 % (70/411) in Beira and 25.6 % (110/429) in Nampula were underage. Over half reported performing sex work to afford daily living, and 29.7–50.0 % had unprotected sex with their last client. The proportion of underage FSW having accessed care and prevention services was lower compared to adult FSW. While HIV prevalence among underage FSW was lower than in adults, it increased markedly with age. Our results point to the urgency of expanding prevention and care programs geared towards underage FSW.

Keywords: Underage, FSW, HIV, Prevention, Mozambique

Introduction

Female sex workers (FSW) are at higher risk for HIV than the general population [1, 2]. Most studies in Southern Africa have found that more than half of FSW were infected with HIV [2]. Other studies estimate that 20–40 % of FSW enter the industry at the age of 16 years or younger and may be at higher risk of sexual and physical violence, HIV/STI infection, and suicide [3]. Yet, research that actually documents violence against FSW is lacking globally [4], and underage FSW are frequently excluded from HIV research and programs, including from clinical trials to prevent HIV [3]. The involvement of underage women in sex work (defined as FSW younger than 18 years old) has been documented in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Americas [2, 3, 5]. However, data on underage FSW and their risk factors for HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa are rare [2, 3]. Thus, there is an urgent need for quantitative research that identifies health needs and the conditions that force underage women into sex work, and can help protect them from exploitation [5, 6].

Mozambique, situated in Southern Africa, has a high prevalence of HIV among the general population, estimated at 11.5 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 10.3–12.6 %) in 2009. HIV prevalence is higher among women (13.1 %, CI 11.7–14.5 %) compared to men (9.2 %, CI 8.0–10.4 %) [7]. HIV infections among sex workers, their clients, and the partners of their clients are regarded as important contributors to the HIV epidemic in Mozambique [8] comprising 19 % of infections according to a 2008 modes of transmission report [9].

Published [10–12] and unpublished [13–15] literature has documented the involvement of underage women in transactional sex in Mozambique. Transactional sex is understood as offering sex in exchange for goods, services or money, which can be part of relatively stable sexual relationships that may not necessarily be defined as commercial by those involved in them. However, the factors that can put these underage women at risk of HIV infection have yet to be documented in Mozambique. Additionally, few studies have focused specifically on underage women involved in commercial sex (exchange of sex explicitly for money), as opposed to transactional sex. Three integrated bio-behavioral surveillance (IBBS) surveys implemented in 2011–2012 in Mozambique estimated that 2.0–5.0 % of women aged 15 or older in the three main urban areas of the country (Maputo, Beira, and Nampula) were FSW [16]. The surveys do not, however, provide population size estimates for underage FSW specifically.

The present analysis, focusing specifically on commercial sex, is based on data from the three IBBS surveys in Mozambique. FSW were defined as biological females aged 15 years or older, who had received money in exchange for sex from a man other than a main partner in the 6 months preceding their participation in the survey. This analysis compares differences in socio-demographic, behavioral and health characteristics of underage (15–17 years old) and adult (≥18 years old) FSW in the three main urban areas of Mozambique. An underage person was defined as per Article I of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child as a human being under the age of 18 [17]. The decision to include underage women (age 15–17) in the survey was carefully assessed [18]. Based on evidence from other studies in Mozambique [12, 14], the exclusion of this age group from surveillance would result in failure to collect valuable data, useful for policy and programmatic purposes, potentially causing more harm to the population. For the individual participant, the survey provided a unique opportunity to receive free counseling specific to their individual needs and risk factors, in a safe environment, where participants were linked to FSW and youth friendly health and social services. Additionally, the results of the survey provide valuable information that can be used to develop much needed interventions aimed at the prevention of underage sex work and mitigation of health problems for this vulnerable population.

The aim of this analysis is to draw attention to the problem of underage women engaging in sex work, contribute to understanding of characteristics and factors that can place underage FSW at risk of HIV infection and provide information to assist with the design of HIV prevention programs relevant to this sub-population in Mozambique and in Southern Africa [3].

Methods

Overall Study Design, Target Population, Recruitment, and Sampling

The study sample was obtained from three IBBS surveys among FSW conducted in 2011–2012 in Maputo, Beira, and Nampula, the main urban areas in Mozambique. These IBBS surveys aimed to estimate HIV prevalence and associated risk factors, evaluate access to and use of healthcare services, and estimate the size of the FSW population aged 15 years and over in each area. Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) has been used in several other countries to study hard to reach populations and has been described in detail elsewhere [19–22].

The studies began with a formative assessment phase that included ethnographic mapping of FSW venues and social networks. Data for this phase were collected through focus group discussions, observation, and key informant interviews with active FSW, former FSW, and providers working with FSW. The formative assessment identified potential “seeds” to launch recruitment chains for the main survey. Seeds were drawn from distinct geographic areas and comprised a diverse set of demographic characteristics in each area. Participants were recruited in each survey area using RDS, an approach of long-chain peer referral sampling which, if theoretical assumptions are met and implemented, can provide probability-based or representative estimates of the target population [22].

Study eligibility criteria included: being a biological female aged 15 years or older; having received money in exchange for sex from a man other than a main partner in the last 6 months; living, working, or socializing in the survey areas; being in possession of a valid referral coupon received from an FSW peer; and being capable and willing to provide a written informed consent. Previous participation in the survey or inability to provide informed consent, including being under the influence of alcohol and drugs, were reasons for exclusion. Nationality was not an exclusion criterion.

After verifying participant eligibility, obtaining informed consent, completing the survey and HIV/STI counseling and testing, survey personnel gave each participant three to five referral coupons and instructed them to randomly refer FSW who were part of their social networks using the coupons. This pattern of recruitment through referral using a coupon was maintained until the desired survey sample size was achieved and equilibrium (i.e., stability in the make-up of the sample with respect to key variables) was reached in each of the survey areas. Equilibrium was checked weekly during recruitment. Equilibrium variables included age group, educational level, student status, marital status, place of last client pick-up, contact with peer educators, neighborhood of residence, network size, number of clients in the last month, known HIV status and rapid HIV test result. Each participant received a primary incentive for their participation in the survey and a secondary incentive for each additional participant successfully recruited (someone they referred, who was eligible and who participated in the survey). The primary incentive consisted of a beauty/health kit, valued at ~$8 USD and reimbursement for transportation (~$2 USD). The secondary incentive consisted of ~$2 USD worth of mobile phone voucher for each participant successfully recruited to compensate for costs associated with locating and inviting the participant to the survey. These costs were decided upon in the formative research, which ensured that values were sufficient to cover costs while not overly high so as to be coercive.

Measures

A standardized questionnaire adapted for the Mozambican context was used to collect participants’ behavioral and social network data. Questionnaire domains included: socio-demographic information; sex work and sexual history; sexual behavior and risks with the two most recent clients and two most recent non-clients; condom usage; HIV and AIDS program exposure; HIV knowledge; knowledge of STI and self-reported STI infection; healthcare access and healthcare-seeking behavior; HIV testing history; HIV care and treatment; experience of stigma and discrimination; use of alcohol and non-medically prescribed drug use; and social network size. Alcohol misuse was measured using the Alcohol Use Identification Disorders Test (AUDIT)-C screening tool [23]. Dried blood spots (DBS) were used to collect blood specimens, which were tested in the central laboratory of the National Institute of Health (Instituto Nacional de Saúde - INS) in Maputo City, Mozambique, using a testing algorithm consisting of three sequential ELISA tests.

Study participants gave separate written informed consent before engaging in each procedure, including: completion of the behavioral questionnaire, rapid HIV testing with return of results, and preparation of DBS samples to be sent to the INS for storage and laboratory testing for HIV.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee for Health (Comité National de Bioética para a Saúde - CNBS) in Mozambique and the Committee on Human Research (CHR) of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) in the United States of America. The age of adulthood in Mozambique is 18 years old. However prior qualitative studies have found that underage women were also engaged in sex work [24, 12, 14]. Ethical approval to interview sex workers aged 15–17 who were able to provide consent based on their status as emancipated underage persons was granted by the committees above. If desired, women, including underage FSW, were linked to the Office for Women and Children of the Mozambican police, under the Ministry of the Interior, which provides access to the legal system in a safe environment to victims of violence. They were also referred to the Mozambican League of Human Rights which provides legal counsel free of charge.

Analysis

Each participant’s behavioral questionnaire was entered into a QDS™ database and HIV test results were entered into a Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro) database. The databases were merged, checked and cleaned using R version 2.15 (R Development Core Team, 2011). Data from the three surveys were not merged given the RDS sample was drawn from different cities with distinct networks and cultural contexts. RDS Analyst [25] was used to check for equilibrium, homophily/heterophily and cross-group recruitment, and to generate weighted estimates. We ran several diagnostics, including bottleneck plots, to assess that the underlying assumptions of RDS had been met. Having found no evidence of bottlenecking or trapping of chains within distinct networks with respect to key variables (e.g., age), we analyzed the data using a single estimator across the indicators. Weighted Chi square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare differences in proportions between underage and adult FSW.

Results

Study Sample and Socio-demographic Characteristics of Underage FSW

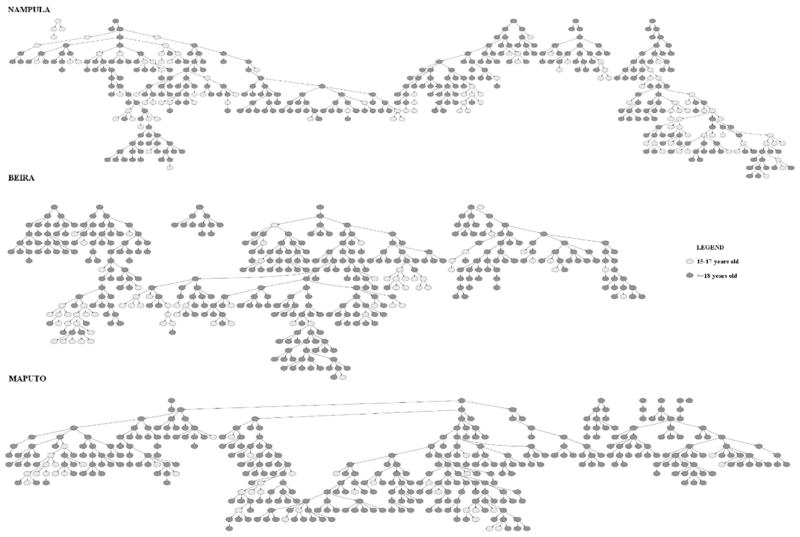

A total of 1240 FSW aged 15 years and older participated in the three surveys; 400 in Maputo, 411 in Beira, and 429 in Nampula. Of these, 17.7 % (219) were aged 15 to 17 years with 9.8 % in Maputo (n = 39), 17.0 % in Beira (n = 70), and 25.6 % in Nampula (n = 110). Survey recruitment was completed in 14 waves in Maputo, and 19 in Beira and Nampula. Equilibrium was achieved in all three areas for key variables, including age group, educational level, place of last client pick-up, and contact with peer educator. Figure 1 presents recruitment tree diagrams with color nodes indicating participant age group (age 15–17 vs 18 and older). Recruitment homophily was close to one in all three cities (1.05 in Maputo, 1.11 in Beira and 1.16 in Nampula) within these groups.

Fig. 1.

RDS recruitment trees and homophily estimates for recruitment of underage FSW [15–17] and adult FSW (≥18) in Mozambique 2011–2012

Table 1 presents socio-demographic and sex work characteristics of underage FSW for each urban area. Among underage FSW, 51.7 % in Maputo, 77.7 % in Beira, and 87.5 % in Nampula were attending school at the time of the survey. The majority of underage FSW (64.6–74.5 %) had completed primary school, and between 52.1 and 70.8 % spoke a local language in their household as opposed to Portuguese. Among underage FSW in Maputo, Beira, and Nampula, 32.1, 48.0 and 29.0 %, respectively, had been away from home for more than one month in the six months before the study, and more than six in 10 had at least one stable, non-client partner in the last six months. In Maputo, Beira, and Nampula, 14 (28.4 %), 21 (30.8 %), and 30 (25.6 %) underage FSW had ever been pregnant and 8 (21.6 %), 12 (13.9 %), and 16 (9.3 %) had ever had an abortion, respectively.

Table 1.

RDS-adjusted characteristics of underage female sex workers (FSW) age 15–17 year olds in Mozambique 2011–2012

| Maputo

|

Beira

|

Nampula

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 39)

|

(n = 70)

|

(n = 110)

|

|||||||

| n | % Crude | % Wtd. (95 % CI)a | n | % Unadj. | % Wtd. (95 % CI)a | n | % Unadj. | % Wtd. (95 % CI)a | |

| Was attending school at the time of the survey | 19 | 48.7 | 51.7 (20.9, 82.7) | 56 | 80.0 | 77.7 (45.7, 100) | 101 | 91.8 | 87.5 (72.2, 100) |

| Completed primary school | 26 | 66.7 | 74.5 (37.8, 100) | 45 | 64.3 | 64.6 (50.8, 78.5) | 80 | 72.7 | 73.9 (58.0, 89.8) |

| Spoke a local languageb at home (as opposed to Portuguese) | 25 | 64.1 | 61.8 (16.6, 100) | 49 | 70.0 | 70.8 (56.5, 85.2) | 51 | 46.4 | 52.1 (29.9, 74.3) |

| Was away from home more than 1 month in the last 6 months | 13 | 33.3 | 32.1 (3.5, 60.9) | 32 | 45.7 | 48.0 (22.8, 73.3) | 32 | 29.1 | 29.0 (7.7, 50.5) |

| Had at least one stable, non-client partner in the last 6 months | 25 | 64.1 | 74.4 (64.0, 85.0) | 58 | 82.9 | 83.4 (70.2, 96.7) | 75 | 68.2 | 69.4 (52.5, 86.4) |

| Currently or ever married | 4 | 10.3 | 6.1 (0.0–22.0) | 6 | 8.6 | 9.6 (2.0–17.2) | 3 | 2.7 | 8.9 (0.0–23.5) |

| Ever pregnant | 14 | 35.9 | 28.4 (2.6, 54.2) | 21 | 30.0 | 30.8 (2.4, 59.3) | 30 | 27.3 | 25.6 (10.9, 40.4) |

| Ever had an abortion | 8 | 20.5 | 21.6 (0.0, 51.2) | 12 | 17.1 | 13.9 (0.0, 35.8) | 16 | 14.5 | 9.3 (2.5, 16.2) |

| Earned money from activities other than sex work in past month | 6 | 15.4 | 14.1 (7.6, 20.7) | 15 | 21.4 | 19.9 (5.7, 34.1) | 12 | 10.9 | 14.9 (7.6, 22.2) |

| Initiated sex work over 2 years before the survey | 6 | 15.4 | 18.7 (8.6, 28.9) | 10 | 14.5 | 16.4 (4.0, 28.9) | 14 | 12.7 | 11.1 (0.0, 22.8) |

| Was under the age of 15 when initiated sex work | 9 | 23.7 | 23.0 (0.0, 51.3) | 13 | 18.8 | 19.8 (7.1, 32.7) | 37 | 33.6 | 31.3 (13.6, 49.1) |

| Performed sex work to afford daily livingc | 25 | 64.1 | 68.2 (28.8, 100) | 60 | 85.7 | 85.5 (70.5, 100) | 64 | 58.2 | 49.0 (33.9, 64.2) |

| Performed sex work to pay for schoolingc | 8 | 20.5 | 23.2 (1.5, 44.9) | 11 | 15.7 | 20.9 (9.6, 32.3) | 44 | 40.0 | 32.4 (16.4, 48.6) |

| Performed sex work to pay for extra luxuryc | 5 | 12.8 | 12.6 (6.9, 18.5) | 15 | 21.4 | 18.9 (3.1, 34.9) | 43 | 39.1 | 41.7 (21.4, 62.0) |

Adjusted using the RDS-II estimator in RDS Analyst

Primary local languages are Tsonga (Changana)/Ronga in Maputo, Sena/Ndau in Beira, and Macua in Nampula

Multiple choice question

Six (14.1 %, Maputo), 15 (19.9 %, Beira), and 12 (14.9 %, Nampula) underage FSW earned money from activities other than sex work in the month before participating in the survey. About one in 10 had initiated sex work over two years before the survey, with 23.0, 19.8, and 31.3 % having done so under the age of 15. In Maputo, Beira, and Nampula, the majority of underage FSW reported having performed sex work in the past 6 months in order to meet daily needs and 8 (23.2 %), 11 (20.9 %), and 44 (32.4 %) underage FSW, respectively, reported having done so to pay for schooling.

Sexual Behaviors

In Maputo, Beira, and Nampula, 43.2, 27.6, and 51.8 % of underage FSW had at least three partners in the last month (Table 2). Approximately half of underage FSW (43.0, 43.2, and 62.9 %) had unprotected sex with their last non-client partner, and 30.2, 39.5, and 55.2 % had unprotected sex with their last client in Maputo, Beira, and Nampula. In Maputo, a higher percentage of underage FSW had unprotected sex with their last client compared to adult FSW (p < 0.001). The main reasons given by participants ages 15–17 for not having used a condom the last time they had sex with their last client was partner refusal (42.9 %) and not having a condom (26.5 %) (data not shown). In Maputo and Nampula, about one-third of underage FSW were at least 10 years younger than their last client.

Table 2.

RDS-adjusted behavioral and health characteristics of underage (15–17 year olds) and adult (≥18 year olds) FSW in Mozambique 2011–2012

| Maputo

|

Beira

|

Nampula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 15–17

|

Ages ≥ 18

|

Wtd. Χ2 |

p- value |

Ages 15–17

|

Ages ≥ 18

|

Wtd. Χ2 |

p- value |

Ages 15–17

|

Ages ≥ 18

|

Wtd. Χ2 |

p- value |

|||||||||||||

| (n = 39)

|

(n = 361)

|

(n = 70)

|

(n = 341)

|

(n = 110)

|

(n = 319)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

na | % Crude |

% Wtd. |

|||||||

| Had more than 3 clients in the last month | 22 | 57.9 | 43.2 | 239 | 67.7 | 61.9 | 69.4 | <0.001 | 21 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 139 | 41.5 | 36.0 | 4.7 | 0.03 | 62 | 56.9 | 51.8 | 197 | 63.3 | 54.6 | 2.9 | 0.088 |

| Had any unprotected sex with last client | 11 | 29.7 | 30.2 | 53 | 15.2 | 18.6 | 38.7 | <0.001 | 26 | 37.7 | 39.5 | 156 | 46.0 | 47.5 | 4.0 | 0.047 | 55 | 50.0 | 55.2 | 171 | 53.9 | 50.4 | 1.8 | 0.186 |

| Had any unprotected sex with last non-client | 9 | 47.4 | 43.0 | 103 | 47.9 | 49.7 | 4.8 | 0.029 | 24 | 42.1 | 43.2 | 123 | 45.6 | 50.2 | 2.5 | 0.117 | 53 | 63.9 | 62.9 | 149 | 63.7 | 61.9 | 0.1 | 0.801 |

| Was at least 10 years younger than last client | 13 | 33.3 | 36.4 | 117 | 33.2 | 33.1 | 2.5 | 0.114 | 6 | 9.2 | 11.2 | 108 | 35.8 | 37.0 | 43.1 | <0.001 | 33 | 30.3 | 28.3 | 123 | 38.8 | 38.4 | 8.3 | 0.004 |

| Had comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS | 18 | 46.2 | 42.1 | 186 | 51.7 | 52.7 | 22.0 | <0.001 | 43 | 61.4 | 59.8 | 208 | 61.2 | 62.4 | 0.5 | 0.502 | 51 | 46.4 | 47.4 | 174 | 54.7 | 54.7 | 4.0 | 0.046 |

| Knew where to go for HIV testing | 31 | 79.5 | 70.4 | 350 | 97.2 | 96.5 | 479.0 | <0.001 | 47 | 67.1 | 66.4 | 308 | 90.6 | 91.3 | 81.5 | <0.001 | 89 | 80.9 | 71.1 | 295 | 92.8 | 91.0 | 58.2 | < 0.001 |

| Ever tested for HIV | 13 | 33.3 | 21.2 | 292 | 81.1 | 83.7 | 985.5 | <0.001 | 35 | 50.0 | 51.8 | 244 | 71.8 | 66.5 | 14.3 | <0.001 | 37 | 33.6 | 30.2 | 222 | 69.8 | 71.2 | 129.2 | < 0.001 |

| Had contact with peer educators in the last 6 months | 3 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 70 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 84.8 | <0.001 | 9 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 64 | 18.8 | 18.3 | 2.2 | 0.141 | 18 | 16.4 | 13.0 | 93 | 29.2 | 28.4 | 24.1 | < 0.001 |

| Participated in an educational session on HIV/AIDS in last 6 months | 17 | 43.6 | 30.2 | 138 | 38.3 | 35.8 | 6.8 | 0.009 | 21 | 30.0 | 29.5 | 147 | 43.2 | 40.8 | 8.1 | 0.004 | 18 | 16.4 | 13.3 | 93 | 29.2 | 31.1 | 30.4 | < 0.001 |

| Received free condoms in the last 6 months | 20 | 51.3 | 39.6 | 224 | 62.2 | 61.6 | 96.2 | <0.001 | 14 | 20.0 | 22.2 | 124 | 36.5 | 33.7 | 12.9 | <0.001 | 56 | 50.9 | 49.2 | 167 | 52.5 | 51.7 | 0.5 | 0.486 |

| Ever used a female condom | 4 | 10.3 | 7.6 | 98 | 27.2 | 25.1 | 91.8 | <0.001 | 6 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 51 | 15.0 | 14.7 | 2.1 | 0.151 | 21 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 65 | 20.4 | 18.2 | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| Used a healthcare service in the last 6 months | 9 | 23.1 | 28.2 | 158 | 43.9 | 43.4 | 46.4 | <0.001 | 16 | 22.9 | 23.7 | 124 | 36.5 | 39.5 | 16.5 | <0.001 | 37 | 33.6 | 35.7 | 146 | 45.9 | 39.6 | 1.2 | 0.272 |

| Consumed alcohol in a manner indicative of abuse (AUDIT-C) | 13 | 34.2 | 29.6 | 167 | 47.6 | 49.4 | 75.6 | < 0.001 | 31 | 44.3 | 44.4 | 173 | 51.0 | 53.3 | 4.9 | 0.027 | 20 | 18.2 | 14.9 | 165 | 51.9 | 52.9 | 109.6 | <0.001 |

| Experienced sexual or physical violence in the past 6 months | 6 | 15.4 | 13.0 | 33 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 7.0 | 0.008 | 18 | 25.7 | 24.4 | 79 | 23.3 | 22.7 | 0.3 | 0.609 | 28 | 25.5 | 25.2 | 88 | 27.8 | 27.1 | 0.4 | 0.551 |

| Had an STI symptom in the last 6 months | 14 | 35.9 | 46.0 | 90 | 24.9 | 26.1 | 93.4 | < 0.001 | 16 | 22.9 | 25.2 | 147 | 43.1 | 43.3 | 20.7 | <0.001 | 17 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 78 | 24.5 | 25.8 | 6.6 | 0.01 |

| Had HIV | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 144 | 40.1 | 38.6 | 328.2 | < 0.001 | 4 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 113 | 33.1 | 30.3 | 51.2 | <0.001 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 78 | 24.5 | 24.8 | 74.9 | <0.001 |

Percentages do not always add up to totals due to missing data

HIV Knowledge and Access to Services

About half of underage FSW had comprehensive knowledge about HIV1 in the three urban areas, but this knowledge was lower than among adult FSW in Maputo and Nampula (p < 0.001 and p = 0.046, respectively) (Table 2). Significantly fewer underage FSW knew of a place to be tested for HIV, while knowledge of test locations was almost universal among adult FSW (70.4 vs. 96.5 % in Maputo, 66.4 vs. 91.3 % in Beira, and 71.1 vs. 91.0 % in Nampula). A lower proportion of underage FSW than adult FSW had ever tested for HIV prior to the survey in Maputo (21.2 vs. 83.7 %), Beira (51.8 vs. 66.5 %), and Nampula (30.2 vs. 71.2 %).

The proportion of underage FSW who had contact with peer educators was lower in Maputo and Nampula (3.6 vs. 19.3 and 13.0 vs. 28.4 %, respectively). In Maputo and Beira the percentages of underage FSW who had received free condoms in the last 6 months were lower compared to adult FSW (39.6 vs 61.6 and 22.2 vs. 33.7 %, respectively). The percentage of underage FSW who had ever used a female condom was lower compared to adult FSW in Maputo (7.6 vs. 25.1 %). The proportion of underage FSW having used a healthcare service in the past 6 months was lower compared to adult FSW in Maputo and Beira.

Health Characteristics

At least three in every 10 underage FSW in Maputo and Beira consumed alcohol in a manner indicative of abuse, as per the AUDIT-C indicator [23]. Between 13.0 and 25.2 % of underage FSW had experienced sexual or physical abuse in the 6 months preceding the survey.

HIV prevalence among underage FSW was lower compared with adult FSW in each urban area (p < 0.01). All HIV test results among participants younger than 18 in Maputo were negative, while 38.6 % of adult FSW were HIV-positive. In Beira, HIV prevalence was 4.9 % (4/70) among underage and 30.3 % among adult FSW; in Nampula 0.4 % (2/110) of underage and 24.8 % of adult FSW were HIV infected. A higher percentage of underage FSW in Maputo had an STI symptom in the 6 months preceding the survey compared to adult FSW (46.0 vs. 26.1 %, p <0.01).

Discussion

Our data provide new insight to an understudied sample of FSW in Mozambique and can help fill gaps in our understanding of this vulnerable population in the country. The study revealed that an important proportion of FSW (one in six) are under the age of 18, and that approximately one in five underage FSW initiated sex work when younger than 15. To put into context, in Mozambique approximately one in five adolescents age 15–17 had sex for the first time within the same time frame underage FSW in our sample initiated sex work [27].

Unprotected sex and pregnancy were common among underage FSW in the three surveys, and prevention services were far less likely to reach underage than adult FSW. In all three cities, although HIV testing levels were higher among underage FSW than among the general population of girls ages 15–17 (19 %) [7], they were significantly lower than among adult FSW. Moreover, fewer underage FSW in our study knew where to get tested and had accessed prevention or health services than adult FSW, including services such as peer outreach, educational sessions on HIV, free condoms, and healthcare.

As many as one-third of underage FSW in Maputo and Nampula were at least 10 years younger than their last client. The proportion of girls ages 15–17 in the general population of Mozambique having intergenerational sex is 8.4 % [27]. This finding is concerning in that intergenerational sex often compromises the ability of younger women to use a condom. Further, this acquisition from older men may be a source of infection to boys and young men who are also the partners of these FSW. These boys and young men, in turn may later transmit the infection to their younger female partners—a cycle that is a necessary condition to propagate a generalized, heterosexual epidemic. The phenomenon may be widespread as general population studies in Mozambique [7] and throughout sub-Saharan Africa [28] have shown a pattern of young age of infection among girls and older age of infection among boys.

Other factors highlight the risks to underage FSW. As many as one quarter of underage FSW experienced violence in the 6 months preceding the interview in two urban areas. Most underage FSW have both clients and regular non-client partners where condom use is low and comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS is incomplete. Some factors contributed differently to the risk profile for different cities. For example, alcohol misuse appeared to be less of a factor for underage FSW in Nampula.

There are limitations to our study. First, peer recruitment assumes FSW are socially connected and have freedom of movement and the ability to choose to participate in the study. The surveys on which this analysis is based may not have included those held forcibly or under close scrutiny in such venues as brothels, as described elsewhere in the world [3]. While our surveys’ data and our formative assessment did not identify such contexts in Mozambique, this area needs further exploration. RDS recruitment methods require peers to recognize each other as FSW and to some degree self-identify as FSW. Our cross-sectional study does not capture the sequence of events that might force or lead an underage woman into sex work. Moreover, the IBBS surveys were not designed specifically to examine underage FSW and the sample size for many variables was small, affecting overall precision. These limitations need to be addressed with studies of larger scale that are designed to look at this underage population.

Despite limitations, the surveys successfully recruited a large number of underage FSW and we were able to describe their socio-demographic characteristics, behavior, knowledge, and service access. Our data identified the existence of a sizeable number of underage women engaged in sex work in Mozambique, a serious violation of human rights that requires attention [6].

The gap in HIV testing and outreach to underage FSW needs to be addressed through scale up of FSW-friendly activities overall, with special emphasis on reaching younger ones. Given the high proportion of underage FSW currently studying, schools may be a viable avenue to reach them. In fact, our results suggest that underage FSW may be turning to sex work in order to afford secondary or higher levels of education. This may well be a primary driver of underage sex work in Nampula, located in a province lacking education infrastructure [29] where 32.1 % of women ages 15–49 had never completed any schooling [27]. In other Southern African contexts, structural interventions such as reduction of schooling costs or cash payments have been shown to reduce HIV risks and STIs, while also increasing school attendance [30, 31].

Although the prevalence of HIV among underage FSW was low compared to adult FSW in our sample (with no infections detected among the underage in Maputo), the prevalence of recent self-reported STI symptoms was high with as many as 46 % having had one in Maputo. However, less than three in 10 underage FSW had used a healthcare service and less than one in 10 had been in contact with a peer educator in the last 6 months. These results point to the opportunity to expand prevention interventions in this population. Geração Biz is a clinic and school-based program implemented since 1999 with the aim to expand access to STI/HIV/AIDS services and reproductive health among Mozambicans aged 10–24. In tandem with other similar programs that target young people in Mozambique Geração Biz could be a starting point to promote additional structural and behavioral interventions. Moreover, interventions need to address several other underlying factors contributing to underage sex work; such as social (e.g., gender inequality), legal-political (e.g., laws and regulations concerning underage sex work), historical (e.g., sugar daddies), and economic (e.g., lack of livelihood opportunities) [32].

Other interventions could offer sexual harm reduction methods, by ensuring that evidence-based biomedical interventions (such as PrEP) are made available to all sex workers, including underage FSW. Health care workers could benefit from receiving training in strategies such as Psychological counseling, Reproductive health services, Education, Vaccinations, Early detection, Nutrition and Treatment (PREVENT) that can be provided to adolescent FSW at the community level [6]. Other interventions that could be implemented in Mozambique include public awareness through the media, such as the Meninas da noite (Girls of the night) investigative reports in Brazil [33]; telephone hotlines that provide confidential access to information for potential victims of exploitation; and education and training for police, youth-serving agencies, and politicians [34]. While such interventions for underage women will be politically challenging, findings presented here provide evidence of their need and provide a platform for advocacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank research participants for their courage in accepting to be part of these surveys; the surveys’ field staff and members of the Mozambique IBBS technical working group for their dedication in planning and implementing the surveys; and all implementing institutions for their support at all stages of the surveys. This research has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Mozambique Country Office under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number U2GPS001468. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the CDC or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Comprehensive knowledge about HIV meant correctly responding to questions about the means of transmission and prevention of HIV and rejecting the major misconceptions about HIV transmission. Questions about HIV transmission and prevention where (a) people can reduce their risk of HIV by having only one sexual partner who does not have other sexual partners; (b) people can protect themselves from HIV by using a condom in each sexual intercourse; and (c) an apparently healthy looking person can have HIV. The major misconceptions about HIV transmission used for the indicator were (a) people can become infected with HIV by a mosquito bite; and (b) people can become infected with HIV by sharing a meal with a person infected with HIV. This is the first Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting (GARPR) indicator [26].

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS epidemic: 2012 [Internet] Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. [cited 2013 Jun 26]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lule F, Lo Y-R. Socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral risk factors of female sex workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;16(4):920–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9985-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman JG. Adolescent female sex workers: invisibility, violence and HIV. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(5):478–81. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deering KN, Amin A, Shoveller J, Nesbitt A, Garcia-Moreno C, Duff P, et al. A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):e42–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urada LA, Malow RM, Santos NC, Morisky DE. Age differences among female sex workers in the Philippines: sexual risk negotiations and perceived manager advice. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/812635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis BM, Levy BS. Child prostitution: global health burden, research needs, and interventions. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1417–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Instituto Nacional de Saúde, Instituto Nacional de Estatística, ICF Macro. Inquérito Nacional de Prevalência, Riscos Comportamentais e Informação sobre o HIV e SIDA em Moçambique 2009. Calverton: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mozambican Council of Ministers (Conselho de Ministros de Moçambique) Strategic Plan for the National Response towards HIV and Aids, 2010–2014 (Plano Estratégico Nacional de Resposta ao HIV e SIDA, 2010–2014) 2010 [cited 2013 Jun 26]; Available from: http://cms.nam.org.uk/site/v634849572084170000/file/1053097/Plano_Estrat_c3_a9gico_Nacional_de_Resposta_ao_HIV_e_SIDA__2010___2014.pdf.

- 9.Whitman D, Horth R, Gonçalves S. Analysis of HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission: Mozambique Country Synthesis. Analysis of HIV prevention response and modes of HIV transmission. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groes-Green C. “To put men in a bottle”: Eroticism, kinship, female power, and transactional sex in Maputo, Mozambique. Am Ethnol. 2013;40(1):102–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machel JZ. Unsafe sexual behaviour among schoolgirls in Mozambique: a matter of gender and class. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9(17):82–90. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins K, Price N, Mussá F. Milking the cow: Young women’s construction of identity and risk in age-disparate transactional sexual relationships in Maputo, Mozambique. Glob Public Health. 2009;4(2):169–82. doi: 10.1080/17441690701589813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Barros JG, Taju G. Prostituição, Abuso Sexual e Trabalho Infantil em Moçambique: o caso específico das províncias de Maputo, Nampula e Tete. Maputo City: Terre des Hommes; 1999. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osório C, Mussa E. Violação sexual de menores: estudo de caso na cidade de Maputo : relatório de pesquisa. Maputo: WLSA Moçambique; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvester K, Tinga C, Marcelino C, Mahache D, Zandamela I. Sex Workers in Ressano Garcia and Namaacha Border Posts, and the Southern Transport Corridor in Inhambane Province, Mozambique. Maputo: UNFPA; 2009. Apr, Vulnerability to HIV and AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 16.INS, CDC, UCSF, Pathfinder, I-TECH. Final Report: The Integrated Biological and Behavioral Survey among Female Sex Workers, Mozambique 2011–2012 [Internet] San Francisco: UCSF; 2013. p. 92. Available from: http://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/gsi/IBBS-FSW-Final-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Vol. 1577 United Nations: Nov 20, 1989. Treaty Series. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenk K, Williamson J. Ethical approaches to gathering information from children and adolescents in international settings [Internet] Family Health International. 2009 [cited 2013 Nov 25]. Available from: http://dspace.cigilibrary.org/jspui/handle/123456789/8210.

- 19.Kajubi P, Kamya MR, Raymond HF, Chen S, Rutherford GW, Mandel JS, et al. Gay and bisexual men in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(3):492–504. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto men’s study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):626–34. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnol B, Ernesto C. Titios e Catorzinhas. Pesquisa Exploratoria sobre “Sugar Daddies” Na Zambézia Quelimane E Pebane DFIDPMG Maputo [Internet] 2003 [cited 2013 Aug 14]; Available from: http://www.wlsa.org.mz/lib/publicacoes/SugarDaddies.pdf.

- 25.Handcock MS, Fellows IE, Gile KJ. Software for the analysis of respondent-driven sampling data, Version 0.42. 2014 http://hpmrg.org.

- 26.UNAIDS, UNICEF, World Health Organization. Global AIDS response progress reporting 2013: construction of core indicators for monitoring 2011 political declaration on HIV/AIDS. 2013 [cited 2015 Mar 14]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78126.

- 27.Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Ministério da Saúde Moçambique, MEASURE DHS/ICF Interational. Maputo: 2012. Mar, Moçambique Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011: Relatório Preliminar (Mozambique National Demographic Health Survey 2011: Preliminary Report) [Internet] [cited 2014 Sep 18]. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR14/PR14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gopalappa C, Stover J, Pretorius C. HIV prevalence patterns by age and sex: exploring differences among 19 countries. Calverton: ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro C. Educational decentralization in Mozambique: a case study in the Region of Nampula. In: Daun H, editor. School decentralization in the context of globalizing governance [Internet] Springer; Dordrecht: 2007. pp. 159–74. [cited 2014 Sep 18] Available from: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-4700-8_8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Özler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1320–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baird S, Chirwa E, McIntosh C, Özler B. The short-term impacts of a schooling conditional cash transfer program on the sexual behavior of young women. Health Econ. 2010;19(S1):55–68. doi: 10.1002/hec.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finger C. Brazil pledges to eliminate sexual exploitation of children. Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rekart ML. Sex-work harm reduction. Lancet. 2006;366(9503):2123–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67732-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]