Abstract

China has high rates of antibiotic abuse and antibiotic resistance but the causes are still a matter for debate. Strong physician financial incentives to prescribe are likely to be an important cause. However, patient demand (or physician beliefs about patient demand) is often cited and may also play a role. We use an audit study to examine the effect of removing financial incentives, and to try to separate out the effects of patient demand. We implement a number of different experimental treatments designed to try to rule out other possible explanations for our findings. Together, our results suggest that financial incentives are the main driver of antibiotic abuse in China, at least in the young and healthy population we draw on in our study.

I. INTRODUCTION

China has a high rate of antibiotic use and abuse relative to western countries. A study of 230,800 outpatient prescriptions in twenty-eight Chinese cities found that nearly half the prescriptions written between 2007 and 2009 were for antibiotics and that ten percent were for two or more antibiotics (Li et al., 2012). Antibiotics were prescribed twice as frequently as recommended by the WHO (Li et al., 2012). One of the most dangerous potential consequences of rampant antibiotic abuse is that it will encourage the rise of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” and threaten global health. Antibiotic resistance already appears to be higher in China than in western countries and there has been an alarming growth in the prevalence of resistant bacteria (Zhang et al., 2006).

One possible explanation for antibiotics abuse in China is that, as described further below, most Chinese receive outpatient care from hospitals, and hospitals derive a large fraction of their revenues from drug sales. In turn, physicians generally work for hospitals and receive much of their compensation in the form of bonus which are tied to the revenues that they bring in.

Starting in the early 2000s, China has piloted various reforms intended to reduce the financial incentives to prescribe including the establishment of the National Essential Medicine List in public primary care hospitals and removing pharmacies from hospitals in some secondary and tertiary hospitals (Wagstaff et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013).

To date, these reforms have not proven effective in curbing drug over-prescription (Yip et al, 2012; Feng et al., 2012), and the per capita use of antibiotics in China is still much higher than the recommended level (Yin et al., 2013). There are a number of possible reasons. First, in the absence of any alternative hospital financing method, removing pharmacies from hospitals has often proven infeasible so that perhaps the link between provider financial incentives and prescription has not been broken.

Alternatively, financial incentives may not be the main issue. It is commonly argued that patients demand antibiotics even when they are unlikely to be effective (Cars and Hakansson, 1995; Sun et al., 2009; Bennett et al., forthcoming; Wang et al., 2013). Alternatively, physicians may believe that patients want antibiotics. Or the over-prescription of antibiotics could be due to the lack of professional knowledge about proper antibiotic usage among physicians (Yao and Yang, 2008; Sun et al., 2009; Dar-Odeh et al., 2010). To the extent that patient demand, provider beliefs about patient demand, or provider ignorance are important drivers of antibiotic abuse, then policies reducing providers’ financial incentives to prescribe will not solve the problem.

This paper investigates these issues using a large-scale audit study in China featuring students whom we trained to act as patients with identical mild flu-like symptoms. Our audits were designed to investigate the effects of reducing financial incentives to prescribe, and to distinguish between the effects of financial incentives and the effects of other competing explanations for overuse of antibiotics.

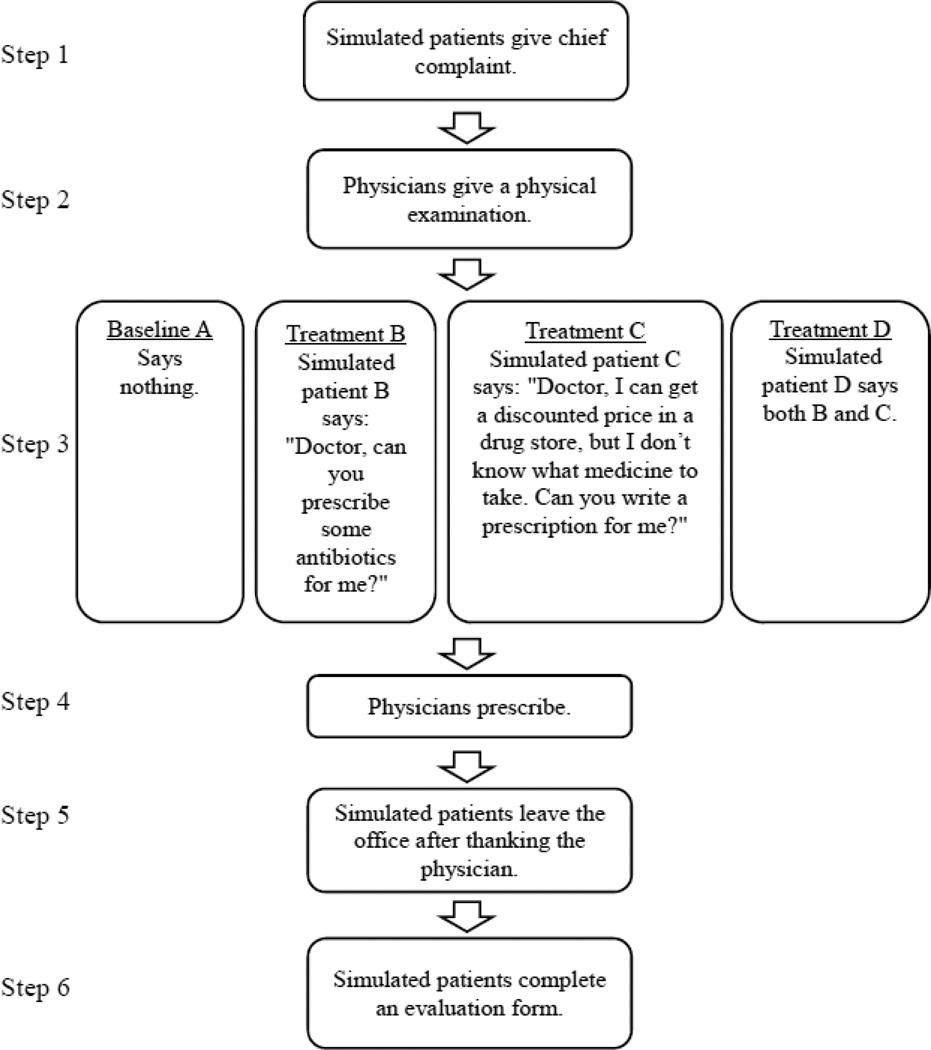

We conducted two experiments. In the first experiment, we sent teams of four well-matched simulated patients to a single physician at each audited hospital. We considered one student to be the baseline (Patient A). This student did not ask for antibiotics. But if the doctor prescribed antibiotics he/she would have assumed that the patient would buy them at the hospital given that this is the general practice. The remaining three students all deviated from this baseline scenario in a specific way: Patient B directly asked the doctor for an antibiotic prescription. This treatment is intended to eliminate uncertainty about whether the patient wants or expects antibiotics to be prescribed. Patient C asked for a prescription (not specifically antibiotics) but indicated that he/she would buy any drugs prescribed in another pharmacy, thereby eliminating the possibility that the hospital would receive a payment for the sale. Patient D both asked specifically for antibiotics and indicated that he/she would buy any drugs prescribed elsewhere.

Overall, 55% of physicians prescribed antibiotics when the patient neither asked for antibiotics nor indicated that he/she would purchase elsewhere. The fraction rose to 85% when patients specifically requested antibiotics, but only if the doctor expected the prescription to be filled in the hospital pharmacy. If the patient indicated that he/she would purchase the drugs elsewhere, only 14% of doctors prescribed antibiotics, even when specifically requested to do so by the patient. This rate is not statistically significantly different from the 10% prescription rate among patients who did not request antibiotics in the treatment in which patients indicated that they would buy elsewhere. Thus, our first experiment suggests that high rates of antibiotic abuse are unlikely to be driven by patient demand or provider ignorance, and that a reform that effectively reduced providers’ financial incentives to prescribe could dramatically reduce antibiotic prescription rates.

However, it is possible that the results in Experiment 1 are driven by some other mechanism. Perhaps doctors are concerned that patients who buy drugs in free-standing pharmacies are more likely to be harmed by counterfeit drugs. Or perhaps doctors are offended by the patient’s suggestion that he or she will buy elsewhere. The second experiment explores these alternative explanations using several additional treatments. First, in the script used in the second experiment, patients indicate that they will buy their drugs from a close relative when they are not shopping at the hospital pharmacy. This change may reduce any fears that the physician may have about the patient receiving counterfeit or harmful drugs, and may also make it seem less offensive that the patient wishes to purchase elsewhere. We find that this change in the script has little impact on the results.

In a second treatment, patients tell doctors that they know (because they have read on the internet) that antibiotics are inappropriate for simple cold/flu symptoms. We find that this treatment also reduces the prescription of antibiotics, though by less than the removal of the financial incentive. Given that second guessing the doctor in this way is likely to be at least as offensive as saying that the patient will buy elsewhere (particularly if elsewhere is the store of a close relative), this result suggests that financial incentives are more important than breaches of patient etiquette in determining antibiotic prescription rates.

In a third treatment, we have patients attempt to establish rapport with a physician by offering a token gift, something that is not uncommon in China. If physicians “punish” aggressive patients by being less likely to prescribe antibiotics, then they ought to “reward” nice patients by being more likely to prescribe. Instead, we find that physicians are slightly less likely to prescribe to patients who have offered a small gift.

These results suggest that financial incentives are indeed the most important determinant of the over-prescription of antibiotics, at least in the hospital markets and in the population of young, healthy patients that we analyze. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section II provides some background information, Section III describes the study design, Section IV explains the empirical model, Section V presents the results of the study, and Section VI marks the conclusion.

II. BACKGROUND

In China, most outpatients are seen by doctors in hospital clinics.1 The central government sets hospital fees at a low level, and historically provided direct transfers to hospitals to cover operating expenses (Hsiao, 1996; Eggleston et al., 2008). Starting in the early 1980s, the government began decreasing financial support to hospitals but did not allow them to increase fees (Yip and Hsiao, 2008). Hence, revenues from drug sales have become more important to hospitals over time.

In 2009, China commenced an extensive health-sector reform including the establishment of the National Essential Medicine List to improve population access to, and reduce the cost of, essential medicines. The official policy as of 2013 is that all public primary care hospitals are required to sell the 307 drugs on the National Essential Medicine List at zero profit and local governments are supposed to make up the resulting shortfall in hospital revenues (State Council of PRC, 2013). However, this requirement amounts to an unfunded mandate on local governments which have not received any new sources of revenue that can be used to cover hospital costs. To date, despite the zero-profit policy, income for most health-care providers has not been separated from prescribing medications (Zhu, 2011; Yang et al., 2013; Yip et al, 2012).

Moreover, only public primary care hospitals are required to sell drugs from the Essential Medicine List at cost. Chinese hospitals are divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels, with the tertiary care hospitals providing the most sophisticated care. A majority of secondary and tertiary hospitals still maintain pharmacies, and it is estimated that 80 to 85% of prescriptions are filled in hospital pharmacies (Sun et al, 2008; Wang, 2006; Yu, et al. 2010). Free-standing pharmacies often offer lower prices, especially for generics (Yang et al., 2010; Sun, 2005) but may lack qualified pharmacists (Fang et al., 2013). Thus, it would be quite reasonable for a patient to ask for a prescription from a hospital, but to try to fill it at a lower price in a free-standing pharmacy, especially if it was a commonly available drug that did not require any specialized formulation or dispensing.

While hospitals have clear incentives to sell drugs, prescriptions are written by individual doctors who are generally salaried employees of the hospitals. The average bonus, calculated on the basis of the revenue that they bring in, accounts for 30% to 40% of physicians’ total salary (Yip and Hsiao, 2008; Yip et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Kickbacks from pharmaceutical companies can provide further economic incentives for physicians to prescribe medication, with physicians receiving payments of up to 20% of the value of the prescription (Liu et al., 2000; Eggleston and Yip, 2004; Yip and Hsiao, 2008).

A recent systematic review based on data from 57 studies of antibiotic utilization in China has shown that, although it has fluctuated with changes in national healthcare policies, use of antibiotics in China is still much higher than the recommended level. The overall percentage of outpatients prescribed antibiotics during 2010–2012 was 45.7% (Yin et al., 2013).

Previous research in other countries suggests that doctors are likely to be influenced by financial incentives. For example, Iizuka (2007, 2012) examines the prescription drug market in Japan and finds that doctors’ prescribing patterns are influenced by the size of the markup that they are allowed to charge on drugs. On the other hand, financial incentives may not be the full story. Das et al. (2012) show that even in the absence of financial incentives, many doctors prescribe unnecessary or harmful treatments in India. It is unclear whether these phenomena reflect incompetence, responses to patient demand, or mistaken beliefs about what patients want.

As discussed above, we aim to separate the financial motive for over-prescription from these other motives by implementing a series of different treatments that not only vary the doctor’s financial incentive to prescribe, but also vary the patient’s expressed demand for a prescription, the patient’s expressed knowledge about the value of prescription, and the extent to which the patient may be viewed as a pleasant cooperative patient (or otherwise).

Audit studies of Medical Care

Audit studies are still unusual in health care and existing studies often have very small samples. In addition to the Das et al. (2012) study discussed above, a second exception is Tamblyn et al. (1997) who conducted a study with 312 audits examining Canadian physicians treating gastrointestinal problems. They found that unnecessary prescriptions were made in about 40% of cases although these physicians had no direct financial incentives to prescribe. Kravitz et al. (2005) conducted an interesting study with 298 audits examining patient requests for a directly advertised anti-depressant. They found that patients’ requests have an effect on physician prescribing behavior.

Lu (2014) conducted a study in which she and another person conducted 98 audits posing as a “family member” of an imaginary elderly patient with diabetes or hypertension in Beijing. She found that doctors prescribe more expensive drugs for insured patients than for uninsured patients when the doctors are told that the drugs will be purchased in the doctor’s own hospital, but not otherwise.

Currie et al. (2011) conducted 229 total audits that can be regarded as precursors of this current study. In the first, they found that 65% of simulated patients with mild cold/flu symptoms in two large Chinese urban areas and 55% of simulated patients in a rural area received prescriptions for antibiotics. In the second, matched pairs of patients in one of the cities went to the same hospital doctor presenting with mild cold/flu symptoms. The patients followed the same script except that one patient said to the doctor “I learned from the internet that simple flu/cold patients should not take antibiotics.” They found that this intervention reduced the prescription of antibiotics by 20 percentage points, from a baseline of 63.3%.

However, while Currie et al. (2011) documented overuse of antibiotics, and showed that one type of intervention reduced it, it did not convincingly separate the effects of financial incentives from the effects of beliefs about consumer demand or other motives. It is possible, for example, that doctors believe that most patients want antibiotics, so that the effect of the treatment was only to demonstrate that some patients actually did not want them.

Currie et al. (2013) conducted an audit study on gift-giving in China. They show that when patients provide a small gift to their physician, the doctor reciprocates with better service and fewer unnecessary prescriptions of antibiotics. They then show that gift giving creates externalities for third parties. If two patients, A and B are perceived as unrelated, B receives worse care when A gives a gift. However, if A identifies B as a friend, then both A and B benefit from A's gift giving.

Our study builds on this previous work by varying financial incentives facing doctors as well as patient’s expressed demand for prescriptions, patient’s expressed knowledge about the value of antibiotics prescriptions, and the extent to which the patient may be viewed as a pleasant cooperative patient (or otherwise). We argue that the later may be influenced both by the assertiveness of the patient and by the gift-giving treatment. We believe our study provides the most compelling evidence to date that in China, the overuse of antibiotics among patients with mild symptoms like those in our audit studies is driven largely by financial incentives.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Audit Study Approach

Ideally, audit studies can be designed to isolate mechanisms through the use of matched pairs of testers and random assignment. In-person audits can provide not only quantitative data on the outcomes of the audit, but also qualitative information on the process of the audit (Pager 2007). We collect quantitative data about whether or not an antibiotic is prescribed, the type of antibiotic, and the price, as well as qualitative information about service quality.

The leading concern about audit studies is that the auditors may not be effectively matched (Heckman and Siegelman, 1993). In our study, effective matching means that the groups of simulated patients are identical from the point of view of the physicians except for specific scripted departures from the baseline. We provided extensive training (described further in the on line Appendix) to ensure that simulated patients behaved in a similar manner and gave the same chief symptoms. We also randomly assigned the patients’ roles so that it is possible to control for hospital and simulated patient fixed effects in all our estimations. As we show below, these controls have little impact on our estimates, suggesting that groups of patients were in fact well matched.

Another concern in an audit study is that the testers’ awareness of the experiment may affect their expectations and/or behaviors and thus influence the results. Our auditors were informed about the design and purpose of the study. We felt that since some of them would have been able to infer information about the study from their roles, it was better to give them all the same information. We tried to minimize the potential impact of this knowledge through training. As discussed further below, simulated patients were trained to dress properly, to strictly follow the standard protocol, and to behave in an even-mannered way during the outpatient visit so that, to the physicians, they differed only in the way indicated by the experimental treatment. Finally, in all but the gift-giving treatment, the intervention occurs after the initial examination so that it is also possible to check that there is no difference (relative to the baseline) in the way the physician treats the patient prior to the interventions.

III. STUDY DESIGN

Our studies were conducted in a large Chinese city between October 2011 and June 2012. In the first experiment we randomly chose 80 hospitals from City A. We trained 20 auditors who were divided into five groups. Each group was assigned 16 hospitals and within each hospital, each group saw only one doctor. Hence a total of 80 physicians were seen in a total of 320 visits.

In the second experiment we randomly choose 60 hospitals also from City A. We trained 15 auditors who were divided into three groups. Each group was assigned 20 hospitals resulting in a total of 300 visits. Within each hospital, each group saw two different doctors so that 120 doctors were seen in all. When the same hospitals were selected in both experiments, we registered to see different physicians.

We designed a standard protocol similar to Currie et al. (2011). In the protocol, the chief complaint for all simulated patients is, “For the last two days, I’ve been feeling fatigued. I have been having a low-grade fever, slight dizziness, a sore throat, and a poor appetite. This morning, the symptoms worsened so I took my body temperature. It was 37°C.” In the baseline, the physician examines the patient and then gives a prescription.

We purposely chose very minor symptoms so that it would be difficult for physicians to determine if the infections were viral or bacterial without further tests. Since antibiotics are only effective in treating bacterial infections, it is important for a physician to know the kind of infection a patient acquires before prescribing antibiotics. According to official guidelines (Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China et al. 2004), antibiotics should only be prescribed when bacterial infections are confirmed by a patient’s symptoms or by blood or urine tests. Doctors faced with these vague symptoms should not have prescribed antibiotics and any antibiotic prescription represents antibiotic abuse. Any prescription of powerful Grade 2 antibiotics is even more concerning as these are supposed to be reserved for serious infections that are resistant to first line antibiotics.

Simulated patients underwent nine hours of group instruction and individual practice, during which they received instructions on the transcript and how to behave, dress, etc. Students were instructed to take about 15 seconds to give the chief complaint, to ensure that they did not speak too fast or too slow. The main goal was to standardize the simulated patients’ performance and appearance. To ensure that simulated patients were well trained, after the group instruction and individual practice, simulated patients tested the protocol twice in primary hospitals before the actual implementation of the first audit study.

Figure 1 provides a brief taxonomy of our treatments in the first experiment. Patients in the baseline group only stated the baseline script. Patients in Treatment B say “Doctor, can you prescribe some antibiotics for me?” Although patient demand is often cited as a driver of antibiotic abuse, it is difficult to know how often patients actually ask for these medications. Yu et al. (2014) conducted a study of primary caregivers bringing children to a clinic for vaccinations in two rural counties in central China. They found that although 61% of parents believed that antibiotics are overused in China, 45% of parents considered it reasonable to request antibiotics directly from physicians, and 53% said they had done this on occasion. However, most parents (82%) also reported that they would not be dissatisfied if physicians rejected their request for antibiotics, and there was no correlation between the acquisition of antibiotics and parents’ satisfaction with physicians. We conclude from this study that it is quite normal, in at least some parts of China, to demand antibiotics but that doctors may not be penalized for refusing them.

Figure 1.

Experiment 1 Protocol

Patients in Treatment C of Experiment 1 say “Doctor, I can get a discounted price in a drug store, but I don’t know what medicine to take. Can you write a prescription for me?" This treatment is intended to directly manipulate the financial incentives of the physician by making it clear that any drugs purchased would be purchased elsewhere. However, it could also have the unintended consequence of offending the physician or raising concern about the quality of drugs that might be purchased elsewhere. Both of these factors could independently cause physicians to reduce their prescription rates, a possibility that is further investigated in Experiment 2.

Patients in Treatment D make both statements, viz. “Doctor, can you prescribe some antibiotics for me? I can get a discounted price in a drug store but I don’t know what medicine to take. Can you write a prescription for me?” In this experiment, all four patients saw the same doctor. In order to avoid becoming conspicuous, in Experiment 1, we had at least a two month separation between the visits of patients C and D (the order of treatments C and D was also randomized so some doctors would have seen C first and some would have seen D first).

Whether physicians prescribe unnecessary antibiotics or not is an important indicator of the quality of medical care, but it is not the only possible indicator or the only thing that matters to patients. To analyze the effects of our treatments on other aspects of the quality of medical care, we asked auditors to complete an evaluation form immediately after leaving the office. The questions covered information about what the physician did during the checkup (e.g. did he/she use a stethoscope); inquiries the physician made (e.g. did they ask about sputum); any advice offered by the physician (e.g. did they suggest more rest); and whether the doctor offered instructions on drug usage or drug side effects. Auditors were also asked to record the doctor’s age (in ranges) and gender, and to provide an evaluation of whether they would recommend the doctor to their own parents on a 1–10 scale.

In order to match patients to doctors, we created a table with the following information for each simulated patient: Case ID, Visit Date, Student ID, Role Assigned, Visit Order Assigned, Hospital ID and Physician ID. In each visit, the patient’s role and his or her visit order was randomly assigned.

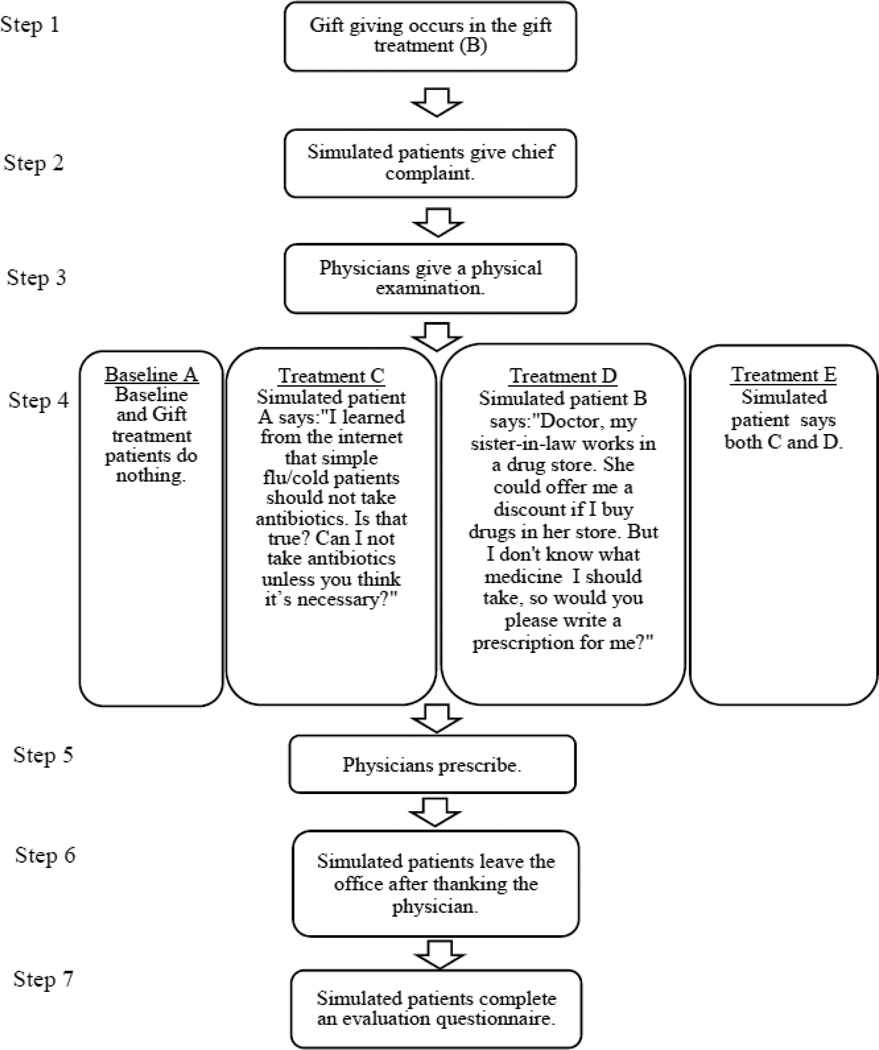

The second study was similar to the first. In this experiment, there were four treatments in addition to the baseline (A). Figure 2 provides a brief taxonomy of these treatments. In Treatment B, a pen worth 1.4RMB is offered at the beginning of the visit.2 The economics literature suggests that gifts can be viewed as a signal of the givers’ intentions with regard to the relationship (Camerer, 1988) and as such, they call for reciprocity (Carmichael and MacLeod, 1997). These considerations suggest that a small gift from the patient to the physician at the start of the visit could lead to more cooperative behavior on the part of the physician.3 In our gift-giving treatment, the patient did not request antibiotics. We expect that doctors in this treatment will be more likely to prescribe antibiotics if they believe that is what patients seek. Conversely, in a gift-reciprocity regime, they should be less likely to prescribe antibiotics if the sole purpose is to generate revenues at the patient’s expense.

Figure 2.

Experiment 2 Protocol

In Treatment C, following the physical examination, the patient says “I learned from the internet that simple flu/cold patients should not take antibiotics. Is this true? Can I not take antibiotics unless they are necessary?” An important consideration when designing an audit study is whether a statement of this type would appear normal to a Chinese doctor, which in turn depends in part on whether a large fraction of the Chinese public are aware of the problem of unnecessary antibiotic use. A large study of university students by Huang et al. (2013) found that 62.8% of nonmedical students (and 82.8% of medical students) believed that drug resistant bacteria had become a problem in China, and 61.8% (vs. 83.9% of medical students) thought that abuse of antibiotics was the main cause of drug resistance. Thus, a doctor might not find it surprising for our auditors to know about this issue, though they might still find a patient who raised the issue to be somewhat aggressive, a thought we return to below.4

In Treatment D, following the physical examination, the patient says “Doctor, my sister-in-law works at a drug store. She can offer me a discount if I buy drugs in her store. But I don’t know what medicine to take, so could you please write a prescription for me?” This change in the script addresses a possible problem with the script in Experiment 1, which is that doctors could be concerned that patients were more likely to receive counterfeit drugs in an outside pharmacy. This concern should be lessened if the patient is patronizing a pharmacy owned by a close relative.

In Treatment E, the patient makes both statements to the physician, indicating that he or she is aware of appropriate antibiotic use, and will purchase any antibiotics prescribed from their relative in any case. Since Treatments D and E involve the same script describing purchasing drugs at a drug store, to avoid suspicion, we instructed Patients D and E to see different physicians in the same hospital.

Appendix Table 2 provides a check on the randomization in Experiment 2. The table shows that there were no significant differences across treatments in the characteristics of the doctor (age and gender), in the number of physicians in the office, in the number of patients in the office, or in the number of patients waiting outside of the physician’s office. Note that since in Experiment 1 all the patients saw the same physician, physician characteristics are balanced across treatments by construction. Further information about our study protocol is available in the on line Appendix.

IV. EMPIRICAL MODELS

Our experimental audit data can be analyzed by comparing means across the baseline and treatment groups. However, as discussed above, one of the main concerns about an audit study is that doctors might react differently to different auditors. Therefore, we also estimate models controlling for physician and patient fixed effects, as well as for the order in which patients were seen. In these models, we cluster the standard errors at the level of the hospital because physicians within a hospital might share important similarities such as facing the same system for determining their bonuses.5

Using the data from Experiment 1, we first estimate models of the following form:

| (1) |

where i indicates the simulated patient, j indicates the physician, Yij is the outcome of interest for simulated patient i's visit with physician j; Buy_Elsewhereij is a dummy equal to 1 if simulated patient i indicates he/she will not purchase drugs at the hospital in the visit with physician j, and 0 otherwise; and Requestij is a dummy equal to 1 if simulated patient i asks the physician for an antibiotic prescription, and 0 if not.

We next estimate models including the visit order in which patients were seen by the same physician, as well as both physician fixed effects and patient fixed effects. These models take the following form:6

| (2) |

where most variables are defined as above. Orderij is a vector of dummy variables indicating whether the patient was the second, third, or fourth patient seen by the doctor, δj is a vector of physician fixed effects, and ηi is a vector of patient fixed effects.

Turning to the second experiment, we first estimate models of the following form:

| (3) |

where once again, Yijk is the outcome of interest for simulated patient i's visit with physician j in hospital k; Giftijk is an indicator for the Gift treatment (B), Displayijk is an indicator for the patient display of knowledge treatment (C), and Buy_Elsewhereijk is an indicator for the treatment in which the patient indicates that he/she will buy drugs elsewhere (treatment D). We also consider the effect of combining the display of knowledge with the buy elsewhere treatment (treatment E).

In the second specification for Experiment 2, we add visit order, hospital fixed effect and control variables including a vector of doctor characteristics and patient characteristics. These characteristics include: patient’s gender, physician’s gender and a categorical variable for the physician’s age, 20–30, 31–40, 41–50 and 51+ years).7

Based on the previous model, our third specification in Experiment 2 also includes patient fixed effects.

| (4) |

where most variables are defined as above, Zj is the vector of doctor characteristics, φk is a vector of hospital fixed effects, and ηi is a vector of patient fixed effects.

Finally, we estimate a model with doctor fixed effects. When including doctor fixed effects, we cannot identify the parameters of Displayijk*Buy_Elsewhereijk in models (3) and (4), since it is collinear with the doctor fixed effects. These models therefore take the following form:

| (5) |

In these models of antibiotic utilization, we expect the λ 1, λ2 and λ3 to be significantly negative if the treatments reduce utilization. When Yijk is a measure of good service quality, we expect λ1 to be positive, and the λ2 and λ3 to be negative.

V. RESULTS

Given the random assignment of patients to treatment groups and to doctors, it is possible to get a good sense of the effects of the different treatments via a comparison of means. Hence, for each set of results, we first discuss the mean differences, and then the regressions described above.

Antibiotics Prescriptions in Experiment 1

Table 1 displays means for the baseline and three treatments for Experiment 1. The first row of Table 1 shows that doctors normally prescribed something for the patient, though they were less likely to prescribe anything if there was no incentive to do so. Our most interesting finding is in the second row. Overall, 55% of physicians prescribed antibiotics in the baseline of Experiment 1. The fraction rose to 85% when patients specifically requested antibiotics, but only if the doctor expected the prescription to be filled in the hospital pharmacy. If the patient indicated that he/she would purchase the drugs elsewhere, only 14% prescribed antibiotics, even when specifically requested to do so by the patient! This rate is not significantly different from the rate of 10% among patients who did not request antibiotics in the no-incentive treatment.

Table 1.

Mean Outcomes for Drug Prescription, Experiment 1

| Baseline A | B_Incentive, Request |

C_Buy Elsewhere, No Request |

D_Buy Elsewhere, Request |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Panel A. Prescription Rates | ||||

| Prescription rate | 1.00 [0.00] |

1.00 [0.00] |

0.85* [0.04] |

0.88* [0.04] |

| Prescription rate for antibiotics (unconditional on prescription) |

0.55 [0.06] |

0.85* [0.04] |

0.10* [0.03] |

0.14* [0.04] |

| Prescription rate for antibiotics (conditional on prescription) |

0.55 [0.06] |

0.85* [0.04] |

0.12* [0.04] |

0.16* [0.04] |

| Panel B. Types of Drugs (Conditional on Prescription) | ||||

| Number of drugs prescribed | 2.63 [0.09] |

3.24* [0.08] |

1.79* [0.07] |

1.97* [0.09] |

| Two or more types of drugs prescribed | 0.85 [0.04] |

1.00* [0.00] |

0.69* [0.06] |

0.73 [0.05] |

| Prescription for Grade 2 antibiotics | 0.15 [0.04] |

0.22 [0.05] |

0.03* [0.02] |

0.03* [0.02] |

| Panel C. Drug Expenditures | ||||

| Total drug expenditure in RMB (unconditional on prescription) |

97.86 [5.86] |

142.20* [6.87] |

38.17* [2.68] |

46.54* [3.40] |

| Total drug expenditure in RMB (conditional on prescription) |

97.86 [5.86] |

142.20* [6.87] |

44.90* [2.33] |

53.19* [3.16] |

| # Observations | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets.

An asterisk indicates that the difference between the baseline and the treatment is significant at the 95% level of confidence.

Panel B shows that we find similar results across treatments for the number of drugs prescribed, whether two or more types of drugs were prescribed, and for whether Grade 2 antibiotics, which are supposed to be reserved for the most serious cases, were prescribed. In the baseline, Grade 2 antibiotics were prescribed 15% of the time. This figure rose to 22% when patients specifically requested antibiotics (although they did not request any particular antibiotic) but dropped to 3% when the patient indicated that he/she would purchase elsewhere. Panel C shows a similar pattern in drug expenditures: Drug expenditures rise with a request for antibiotics when the incentive is in place, but decrease by approximately 50% when patients indicate that they will purchase elsewhere.

Table 2 shows the same results in a regression framework. While our main results are apparent in the means tables, the models we estimate provide additional evidence about the robustness of these findings. We show estimates without controls, and including visit order, physician fixed effects, and patient fixed effects. The even numbered columns show that controlling for these variables has remarkably little effect on our estimates, which are much the same as implied by Table 1. Once again, the main results are that the “buy elsewhere” treatment results in a large reduction in antibiotics prescription, drug expenditures, and the prescription of Grade 2 antibiotics; a request for antibiotics increases all of these variables (except the prescription of Grade 2 antibiotics) when the financial incentive to prescribe is in place but has no impact on prescription patterns when the financial incentive is removed. This last result strongly suggests that consumer demand is not driving antibiotics abuse, and that it is the financial incentives faced by physicians that are most important.

Table 2.

Antibiotics Prescription and Drug Expenditure, Experiment 1

| Conditional on Any Prescription | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Independent Variable |

Antibiotics Prescription | Total Drug Expenditure | Two or More Drugs | Grade 2 Antibiotics | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | ||

| Buy_Elsewhere | −0.43* [0.06] |

−0.46* [0.07] |

−52.96* [5.60] |

−58.04* [7.01] |

−0.16* [0.07] |

−0.16 [0.09] |

−0.12* [0.04] |

−0.13* [0.05] |

|

| Request | 0.30* [0.05] |

0.32* [0.07] |

44.34* [7.79] |

47.07* [8.59] |

0.15* [0.04] |

0.18* [0.05] |

0.07 [0.05] |

0.09 [0.06] |

|

| Buy_Elsewhere * Request | −0.26* [0.07] |

−0.25* [0.09] |

−36.05* [8.63] |

−36.14* [9.32] |

−0.11 [0.08] |

−0.11 [0.10] |

−0.08 [0.05] |

−0.09 [0.06] |

|

| Constant | 0.55* [0.06] |

0.57* [0.12] |

97.86* [5.89] |

103.01* [12.31] |

0.85* [0.04] |

0.84* [0.13] |

0.15* [0.04] |

0.17* [0.06] |

|

| Observations | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 | 298 | |

| R-squared | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.53 | |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Physician fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets. All of the regressions are clustered at the hospital level.

An asterisk indicates significance at the 95% level of confidence.

Service Quality in Experiment 1

The first panel of Table 3 shows that there were no mean differences in service quality across the treatment groups prior to the point that the patient deviated from the baseline script. Panel B however, shows deterioration in service quality with all of our interventions. Having the patient indicate that they will purchase elsewhere reduces the probability that the physician offers advice to the patient (such as drinking more water or getting more rest)8, reduces the probability that the physician responds politely to being thanked, and reduced the probability that our auditors said that they would recommend the physician to their own parents. Panel C shows that even conditional on prescription, doctors were also less likely to instruct patients about drug usage or to give information about drug side effects. It is possible that they felt that the outside pharmacist should do this. Requesting antibiotics also reduced the probability that the physician responded politely to being thanked, suggesting that physicians might see such a request as a questioning of their authority.

Table 3.

Mean Outcomes for Service Quality, Experiment 1

| Baseline A, Exp. 1 |

B_Incentive, Request |

C_Buy Elsewhere, No Request |

D_Buy Elsewhere, Request |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Panel A. Service Quality Before Intervention | ||||

| Physician/nurse takes patient’s temperature |

0.43 [0.06] |

0.56 [0.06] |

0.50 [0.06] |

0.56 [0.06] |

| Physician asks patient about sputum | 0.63 [0.05] |

0.61 [0.05] |

0.59 [0.06] |

0.60 [0.06] |

| Physician uses a stethoscope | 0.41 [0.06] |

0.35 [0.05] |

0.39 [0.05] |

0.38 [0.05] |

| Panel B. Service Quality After Intervention, Unconditional on Prescription | ||||

| Physician offers helpful advice (e.g. drink more water etc. |

0.63 [0.05] |

0.60 [0.06] |

0.39* [0.05] |

0.45* [0.06] |

| Physician responds politely after being thanked |

0.80 [0.05] |

0.70 [0.05] |

0.39* [0.05] |

0.45* [0.06] |

| Treatment Duration (min) | 5.90 [0.13] |

6.01 [0.12] |

3.70* [0.09] |

3.64* [0.09] |

| Patient would recommend physician to own parents |

0.69 [0.05] |

0.66 [0.05] |

0.28* [0.05] |

0.31* [0.05] |

| Panel C. Service Quality After Intervention, Conditional on Prescription | ||||

| Physician asks about allergies | 0.63 [0.05] |

0.60 [0.06] |

0.46* [0.06] |

0.44* [0.06] |

| Physician instructs on drug usage | 0.36 [0.05] |

0.40 [0.06] |

0.06* [0.03] |

0.03* [0.02] |

| Physician voluntarily informs patient of drug side effects |

0.59 [0.06] |

0.56 [0.06] |

0.06* [0.03] |

0.03* [0.02] |

| # Observations | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets.

An asterisk indicates that the difference between the baseline and the treatment is significant at the 95% level of confidence.

Table 4 examines the effects of the experimental treatments on service quality in a regression framework. Since there is little difference between models with and without a full set of controls, only the later are shown. The results show no evidence of differences prior to the interventions specific to each treatment.

Table 4.

Service Quality Unconditional on Prescription, Experiment 1

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Physician or nurse takes patient’s temperature |

Physician asks about sputum |

Physician uses a stethoscope |

Physician offers helpful advice |

Physician responds politely after being thanked |

| Independent Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Buy Elsewhere | 0.09 [0.09] |

−0.05 [0.09] |

−0.01 [0.09] |

−0 23* [0.10] |

−0.40* [0.09] |

| Request | 0.16 [0.09] |

−0.04 [0.08] |

−0.07 [0.08] |

−0.03 [0.09] |

−0.13 [0.08] |

| Buy Elsewhere * Request | −0.06 [0.13] |

0.04 [0.12] |

0.07 [0.12] |

0.03 [0.14] |

0.13 [0.13] |

| Constant | 0.40* [0.17] |

0.64* [0.16] |

0.40* [0.12] |

0 62* [0.16] |

0.79* [0.13] |

| Observations | 320 | 320 | 320 | 320 | 320 |

| R-squared | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Physician fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| After Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Treatment Duration (min) |

Patient would recommend physician to own parents |

Physician asks about allergies |

Physician instructs on drug usage |

Physician informs about side effects |

| Independent Variable | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

| Conditional on Prescription |

Conditional on Prescription |

Conditional on Prescription |

|||

| Buy Elsewhere | −220* [0.19] |

−0.40* [0.08] |

−016 [0.11] |

−0.30* [0.08] |

−0.51* [0.08] |

| Request | 0.20 [0.19] |

−0.04 [0.08] |

−0.04 [0.09] |

0.04 [0.09] |

−0.04 [0.09] |

| Buy Elsewhere * Request | −0.23 [0.24] |

0.02 [0.11] |

−0.04 [0.15] |

−0.09 [0.12] |

−0.04 [0.11] |

| Constant | 5.91* [0.28] |

0.69* [0.12] |

0.62* [0.14] |

0.36* [0.15] |

0.57* [0.13] |

| Observations | 320 | 320 | 298 | 298 | 298 |

| R-squared | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Physician fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets. All of the regressions are clustered at the hospital level.

Columns 8–10 show estimates conditional on a drug being prescribed.

An asterisk indicates significance at the 95% level of confidence.

After the treatment in which doctors are informed that the patient will buy elsewhere, every measure of service quality declines: Doctors are less likely to offer helpful advice, or to respond politely after being thanked. In addition, conditional on prescription, doctors are less likely to instruct on drug usage, inform the patient about side effects. The appointments end up being two minutes shorter, and the auditors are less likely to say that they would recommend the doctor to their own parents.

Antibiotic Use in Experiment 2

Turning to Table 5, our results suggest that both a patient display of knowledge and the buy elsewhere treatment reduced the prescription of antibiotics: The former reduced it by 20 percentage points, while the later reduced it by 51 percentage points. Combining a display of knowledge and “buy elsewhere” resulted in an even smaller rate of antibiotic prescription, though we cannot reject the hypothesis that the effect is the same as stating that the patient will purchase elsewhere alone.

Table 5.

Mean Outcomes for Drug Prescription, Experiment 2

| Baseline A, Exp. 2 |

B_Gift | C_Display | D_Buy Elsewhere |

E_Display+Bu y Elsewhere |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Panel A. Prescription Rates | |||||

| Prescription rate | 0.98 [0.02] |

1.00 [0.00] |

0.97 [0.02] |

0.93 [0.03] |

0.87* [0.04] |

| Prescription rate for antibiotics (unconditional on prescription) |

0.63 [0 06] |

0.50 [0.07] |

0.43* [0.06] |

0 12* [0.04] |

0.08* [0.04] |

| Prescription rate for antibiotics (conditional on prescription) |

0.64 [0.06] |

0.50 [0.07] |

0.45* [0.07] |

0 13* [0.04] |

0.10* [0.04] |

| Panel B. Types of Drugs (Conditional on Prescription) | |||||

| Number of drugs prescribed | 2.49 [0.11] |

2.33 [0.11] |

2.21 [0.11] |

1.88* [0.08] |

1.62* [0.09] |

| Two or more types of drugs prescribed | 0.93 [0.03] |

0.87 [0.04] |

0.83 [0.05] |

0.75* [0.06] |

0.52* [0.07] |

| Prescription for Grade 2 antibiotics | 0.15 [0.05] |

0.12 [0.04] |

0.03* [0.02] |

0.00* [0.00] |

0.00* [0.00] |

| Panel C. Drug Expenditures | |||||

| Total drug expenditure in RMB (unconditional on prescription) |

104.65 [7.14] |

82.89* [6.09] |

71.08* [5.72] |

38.30* [2.98] |

30.55* |

| Total drug expenditure in RMB (conditional on prescription) |

106.43 [7.04] |

82.89* [6.09] |

73.53* [5.64] |

41.04* [2.86] |

35.25* [4.17] |

| # Observations | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets.

An asterisk indicates that the difference between the baseline and the treatment is significant at the 95% level of confidence.

Panel B shows that stating that he/she would buy elsewhere reduced the number of drugs prescribed significantly. However, both a display of knowledge and stating that he/she would purchase elsewhere eliminated the unnecessary prescription of Grade 2 antibiotics, suggesting that a patient display of knowledge might be as effective as separating prescribing and dispensing for this important outcome.

Panel C indicates, that once again, stating that the patient would buy elsewhere had the greatest effect on drug expenditures (from 105RMB to 38RMB). However, a display of knowledge also reduced drug expenditures by about half as much (to 71 RMB). And the offer of a token gift also significantly reduced drug expenditure (to 83 RMB).

The first four columns of Table 6 show estimates from alternative regression models of antibiotic prescription: A model without controls; one with controls, visit order and hospital fixed effects; one with controls, visit order, hospital fixed effects, and patient fixed effects; and one with visit order, doctor and patient fixed effects. These models are estimated on the sample for whom any drug was prescribed. There are only 15 cases in which no drug was prescribed and including these observations has little impact on the estimates. As discussed above, the coefficient on the interaction between “Display*Buy_Elsewhere” is not identified in the last of these models because it is collinear with the doctor fixed effect. Once again, all of the models return coefficients that are strikingly similar to each other. Hence in the remainder of this table and in Table 8, we focus on models similar to those in column 3.

Table 6.

Antibiotics Prescription, Experiment 2, Conditional Any on Prescription

| Dependent Variable: | Antibiotic Prescription | Total Drug Expenditure |

Two or More Types of Drugs |

Grade 2 Antibiotics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| Gift Giving | −0.14 [0.08] |

−0.16 [0.09] |

−0.18 [0.09] |

−0.19 [0.11] |

−27.87* [9.86] |

−0 08 [0.07] |

−0.04 [0.07] |

| Display | −0.20* [0.08] |

−0.18 [0.09] |

−0.19* [0.09] |

−0.2 [0.11] |

−33.12* [10.45] |

−0.15* [0.07] |

−0.1 [0.06] |

| Buy Elsewhere | −0.52* [0.07] |

−0.50* [0.08] |

−0.52* [0.09] |

−0.53* [0.10] |

−64.87* [9.03] |

−0.21* [0.08] |

−0.14* [0.06] |

| Display * Buy Elsewhere | 0.17 [0.09] |

0.1 [0.11] |

0.12 [0.12] |

21.03 [11.68] |

−0.1 [0.13] |

0.08 [0.07] |

|

| Doctor's Age: 31–40 | −0.04 [0.13] |

−0.09 [0.13] |

−3.81 [14.17] |

0.14 [0.24] |

−0.08 [0.05] |

||

| Doctor's Age: 41–50 | 0 [0.17] |

−0.05 [0.16] |

5.18 [14.87] |

0.2 [0.24] |

−0.03 [0.05] |

||

| Doctor's Age: >=51 | 0.04 [0.18] |

−0.02 [0.20] |

14.14 [22.01] |

0.31 [0.28] |

−0.04 [0.07] |

||

| Doctor is Male | 0.08 [0 06] |

0.06 [0.07] |

1.2 [5.19] |

0.12 [5.15] |

0.01 [0.04] |

||

| Patient is Male | 0.03 [0.05] |

||||||

| Constant | 0.64* [0.06] |

0.62* [0.21] |

0.64* [0.20] |

0.60* [0.21] |

131.41* [25.67] |

0.74* [0.30] |

0.23* [0.10] |

| Observations | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 |

| R-squared | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.38 |

| Control variables | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Hospital fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Physician fixed effects | √ | ||||||

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets. All of the regressions are clustered at the hospital level.

An asterisk indicates significance at the 95% level of confidence.

Table 8.

Service Quality Unconditional on Prescription, Experiment 2

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Physician or nurse takes patient’s temperature |

Physician asks about sputum |

Physician uses a stethoscope |

Physician offers helpful advice |

Physician responds politely after being thanked |

| Independent Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Gift Giving | 0.01 [0.06] |

0.07 [0.12] |

0.2 [0.11] |

0.19* [0.09] |

0.06 [0.07] |

| Display | 0.06 [0.07] |

0.04 [0.11] |

0.11 [0 10] |

−0.03 [0.10] |

−0.18* [0.07] |

| Buy Elsewhere | 0.01 [0.06] |

−0.05 [0.11] |

0.04 [0.10] |

−0.19 [0.11] |

−0:35* [0.09] |

| Display * Buy Elsewhere | −0.05 [0.10] |

−0.03 [0.16] |

−0.15 [0 14] |

0.02 [0.15] |

0.15 [0.12] |

| Constant | 0.04 [0.15] |

0.5 [0.31] |

0.32 [0.30] |

0.63* [0.31] |

0.80* [0.27] |

| Observations | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| R-squared | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Control Variables | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hospital fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| After Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Visit Duration (min) |

Patient would recommend physician to own parents (1–10) |

Physician asks about drug allergies |

Physician instructs on drug usage |

Physician informs about side effects |

| Conditional on Prescription |

Conditional on Prescription |

Conditional on Prescription |

|||

| (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Gift Giving | 0.06 [0.50] |

1.45* [0.41] |

0.04 [0.11] |

0.11 [0.09] |

0.11 [0.06] |

| Display | −0.26 [0.49] |

−0.57 [0.51] |

0.05 [0.10] |

0.11 [0.10] |

0.08 [0.06] |

| Buy Elsewhere | −0.69 [0.53] |

−1.13* [0.45] |

−0.04 [0.12] |

−0.32* [0.08] |

−0.06 [0.03] |

| Display * Buy Elsewhere | 0.1 [0.70] |

0.52 [0.60] |

0.05 [0.16] |

−0.09 [0.11] |

−0.04 [0.06] |

| Constant | 4.64* [1.45] |

5.90* [0.96] |

0.51 [0.36] |

0.32 [0.25] |

0.05 [0.11] |

| Observations | 300 | 300 | 285 | 285 | 285 |

| R-squared | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.32 |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Control Variables | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hospital fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient fixed effects | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets. All of the regressions are clustered at the hospital level.

Columns 8–10 show estimates conditional on a drug being prescribed.

An asterisk indicate: significance at the 95% level of confidence.

Consistent with Table 5, Table 6 shows that eliminating the financial incentive to prescribe has the largest effect on antibiotic prescription and the other measures. Moreover, the estimated effect is very similar to that shown in Table 2, suggesting that changing the script to indicate that the patient would buy from a close relative had no impact on the doctor’s behavior. This finding suggests that the reduction in prescriptions in the “buy elsewhere” treatment is unlikely to be motivated solely by concern that the patient might purchase from an unscrupulous vender.

A display of patient knowledge also reduces inappropriate antibiotic prescription and drug expenditures, by about half as much as eliminating the financial incentive. The positive coefficient on the interaction term “Display*Buy_Elsewhere” indicates that once the financial incentive has been eliminated, a display of patient knowledge has no further effect on antibiotic prescription (i.e. the negative coefficient on “Display” is offset). Finally, establishing a rapport with the physician by giving a token gift also has a significant effect on reducing drug expenditures. The effects are a little smaller than those in the “Display” treatment.

Together the estimated effects of the “Display” and “Gift” treatments suggest that the reduction in prescribing in the “Buy Elsewhere” treatment is unlikely to be solely due to doctors who are offended by the idea of patients purchasing elsewhere. Indeed, the “Gift” treatment suggests that if doctors want to reciprocate to a patient who is pleasant and cooperative, they are less likely to prescribe antibiotics.

Service Quality in Experiment 2

Table 7 shows that there were no differences in service quality prior to the specific interventions involved in our treatments. Panel B shows however, that the token gift improved service quality, while stating that the patient would buy elsewhere resulted in worse service. A display of knowledge also resulted in significantly worse service relative to the baseline. Thus, there is some evidence that physicians reciprocate for a small gift through better service quality and some reduction in drug charges, while they retaliate with worse service quality when faced with displays of knowledge or a patient who will purchase drugs elsewhere. Similarly, Panel C shows that even conditional on prescription, doctors never bothered to instruct on the proper use of the drugs they prescribed when the patient stated that they would buy the drugs elsewhere.

Table 7.

Mean Outcomes of Service Quality, Experiment 2

| Baseline A, Exp. 2 |

B_Gift | C_Display | D_Buy Elsewhere |

E_Display+Bu y Elsewhere |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Panel A. Service Quality Before Intervention | |||||

| Physician/nurse takes patient’s temperature |

0.08 [0.04] |

0.08 [0.04] |

0.13 [0.04] |

0.08 [0.04] |

0.10 [0.04] |

| Physician asks patient about sputum | 0.50 [0.07] |

0.55 [0.06] |

0.53 [0.06] |

0.43 [0.06] |

0.48 [0.07] |

| Physician uses a stethoscope | 0.32 [0.06] |

0.48 [0.07] |

0.40 [0.06] |

0.33 [0.06] |

0.33 [0.06] |

| Panel B. Service Quality After Intervention, Unconditional on Prescription | |||||

| Physician offers helpful advice (e.g. drink more water etc. |

0.63 [0.06] |

0.82* [0.05] |

0.58 [0.06] |

0.43* [0.06] |

0.40* [0.06] |

| Physician responds politely after being thanked |

0.80 [0.05] |

0.87 [0.04] |

0.62* [0.06] |

0.45* [0.06] |

0.40* [0.06] |

| Treatment Duration (min) | 4.65 [0.36] |

4.76 [0.20] |

4.48 [0.31] |

4.02 [0.29] |

3.97 [0.27] |

| Patient would recommend physician to own parents |

5.90 [0.32] |

7.27* [0.13] |

5.25 [0.27] |

4.75* [0.21] |

4.67* [0.20] |

| Panel C. Service Quality After Intervention, Conditional on Prescription | |||||

| Physician asks about allergies | 0.51 [0.07] |

0.58 [0.06] |

0.59 [0.07] |

0.50 [0.07] |

0.52 [0.07] |

| Physician instructs on drug usage | 0.32 [0.06] |

0.45 [0.06] |

0.41 [0.07] |

0.00* [0.00] |

0.00* [0.00] |

| Physician voluntarily informs patient of drug side effects |

0.05 [0.03] |

0.15 [0.05] |

0.12 [0.04] |

0.00 [0.00] |

0.00 [0.00] |

| # Observations | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets.

An asterisk indicates that the difference between the baseline and the treatment is significant at the 95% level of confidence.

Table 8 suggests that only gift giving had a significant positive effect on the measures of service quality. Columns (1) to (3) show that in the absence of any intervention, there were no effects on service quality. Column (4) shows that physicians offered a token gift were more likely to offer helpful advice.9 In turn, auditors were more likely to say that they would recommend the doctor to their own parents in the gift treatment. Consistent with Table 7 we find some evidence of a negative reaction to a patient display of knowledge in that doctors are less likely to respond politely after being thanked. However, the “buy elsewhere” treatment had negative effects on multiple measures of service quality, suggesting that overall it had a more deleterious effect.

VI. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We exploit the power of the audit study method to try to get at the mechanisms underlying overuse of antibiotics in China. Our results suggest that reducing financial incentives for physicians to prescribe antibiotics would likely have a large effect on antibiotic abuse. Our “Buy Elsewhere” treatment dramatically reduced inappropriate prescription of antibiotics for cold/flu symptoms, and completely eliminated the unwarranted and dangerous prescription of expensive and powerful Grade 2 antibiotics for these patients.

It is conceivable that doctors do not prescribe in the “Buy Elsewhere” treatment because they are concerned about the problem of counterfeit or harmful drugs. In Experiment 2, we tried to address this issue by having the patient say that they would buy from a pharmacy owned by a close relative. But even a close relative who owned a pharmacy might unknowingly provide such drugs. An alternative approach might involve telling the doctor that the patient would buy from another hospital closer to their home, or perhaps debriefing doctors about why they did not prescribe antibiotics in some instances. We leave these approaches for future research.

A more remarkable result is that a direct request for antibiotics has little effect when prescribing and dispensing are separated, though it does increase antibiotic prescription 30 percentage points to 85% when doctors expect the patient to fill any prescription at the hospital pharmacy. This finding provides evidence about a potential interaction between physician incentives and patient demand: Rather than being an “either/or” situation, perhaps patient demand enables doctors to act on their underlying financial incentives.

Our results suggest that reducing the financial incentive to prescribe may be the most powerful way to reduce antibiotics abuse in China. However, given the difficulty the government has faced in implementing such a policy, it is noteworthy that our results suggest that other methods might also be effective in reducing antibiotics abuse. Patient displays of knowledge about the appropriate use of antibiotics reduced prescription rates significantly (though not by as much as the “Buy Elsewhere” treatment) and virtually eliminated the unnecessary prescription of powerful Grade 2 antibiotics. Perhaps patients could be encouraged to challenge unnecessary prescriptions. Even establishing a relationship with the physician by giving a token gift reduced drug expenditures modestly, suggesting that moving towards a system in which doctors had continuing relationships with patients might also improve prescribing practices.

A final contribution of our study is that we examine the impact of our various treatments on service quality. Removing the financial incentive to prescribe has a negative effect on virtually all measures of service quality (in addition to forcing all patients to make two trips). In contrast, a display of knowledge has relatively minor effects on service quality and giving a gift improves service. Thus, depending on how patients value service and aspects of medical care such as being informed about potential side effects, removing incentives to prescribe might actually make at least some patients worse off. To the extent that the removal of such incentives made it less likely that patients with serious illnesses would receive necessary prescriptions, such costs would also have to be considered.

Highlights.

Addressing Antibiotic Abuse in China: An Experimental Audit Study

Provider financial incentives are a major driver of antibiotic abuse in China.

Chinese patient demand for antibiotics has little effect without financial incentives.

Patients who discuss antibiotic abuse with physicians are less likely to receive them.

Appendix Table 1

Gift Acceptance Decision, Gift Treatment in Experiment 2

| Dependent Variable : Gift Acceptance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Doctor's Age: 41–50 | −0.12 [0.13] |

−0.07 [0.15] |

−0.11 [0.17] |

| Doctor's Age: >=51 | 0.16 [0.19] |

0.21 [0.15] |

0.07 [0.23] |

| Doctor is Male | 0.09 [0.12] |

0.04 [0.12] |

−0.03 [0.13] |

| Patient is Male | 0.18 [0.13] |

0.17 [0.13] |

|

| Share an office | −0.22 [0.37] |

−0.26 [0.44] |

|

| Share an office * Number of other physician in the office | −0.08 [0.24] |

−0.05 [0.37] |

|

| Share an office * Number of other patients in the office | 0.06 [0.29] |

0.05 [0.41] |

|

| Other people paying attention to the gift giving | −0.28 [0.16] |

−0.1 [0.22] |

|

| Constant | 0.67* [0.16] |

0.77* [0.13] |

0.54 [0.43] |

| Observations | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| R-squared | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.51 |

| Visit Order | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient fixed effects | √ | ||

Notes: Standard errors are in brackets Only Treatment A (gift) simulated patients are included. The omitted doctor's age dummy is "Doctor's Age: 31–40".

An asterisk indicates that the variable is significant at the 95% level of confidence.

Appendix Table 2

Randomization Check for Experiment 2

| Variable | Baseline A | B_Gift | C_Displa y |

D_Buy Elsewhere |

E_Display+ Buy Elsewhere |

Equal Means Test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Physician's age | 1.68 [0.10] |

1.68 [0.10] |

1.68 [0.10] |

1.68 [0.10] |

1.67 [0.13] |

1.00 |

| Proportion of male physicians | 0.43 [0.06] |

0.43 [0.06] |

0.43 [0.06] |

0.45 [0.06] |

0.58 [0.06] |

0.97 |

| Proportion of office-sharing physicians | 0.28 [0.06] |

0.28 [0.06] |

0.28 [0.06] |

0.28 [0.06] |

0.30 [0.07] |

1.00 |

| Number of (other) physicians in the office (conditional on office-sharing |

1.71 [0.19] |

1.59 [0.19] |

1.64 [0.17] |

1.64 [0.17] |

1.73 [0.18] |

0.98 |

| Number of (other) patients in the office (unconditional on office-sharing] |

0.56 [0.14] |

0.58 [0.12] |

0.48 [0.13] |

0.58 [0.15] |

0.56 [0.13] |

0.98 |

| Number of (other) patients in the office (conditional on office-sharing) |

2.00 [0.23] |

1.94 [0.18] |

1.71 [0.27] |

2.07 [0.29] |

1.73 [0.18] |

0.76 |

| Number of patients in the waiting areas | 2.72 [0.35] |

2.53 [0.26] |

2.98 [0.50] |

3.00 [0.40] |

3.04 [030] |

0.71 |

| Average Number of patients in the waiting areas (per doctor) |

2.32 [0.35] |

2.07 [0.23] |

2.61 [0.51] |

2.54 [0.41] |

2.44 [0.29] |

0.75 |

| Observations | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |

Notes: Standard deviations are in brackets. The reported p-value is from a test statistic generated by Wilts’ lambda.

Footnotes

In 2009, only 5.3% of practicing physicians in China were family physicians (Dai et al., 2013). The equivalent of a U.S. primary care physician does not really exist, so a visit to a hospital or clinic is often the counterpart to a visit to a physician’s office in the U.S. (Hsiao and Liu, 1996; Yip et al., 1998; Eggleston et al., 2008).

If the doctor refuses the gift, the patient is instructed to make a second attempt saying “This is just a tiny thing to express my gratitude to you the pen back. We consider the treatment to be the offer of the gift, whether or not it was accepted. Overall 60% of the physicians accepted the gift. Appendix Table 1 shows that acceptance was not significantly related to doctor characteristics or characteristics of their offices, but that some patients were more likely to have their gifts accepted.

There is a large literature on gift giving in medical care. It is estimated that pharmaceutical companies spend $19 billion per year marketing to 650,000 prescribing doctors in the U.S. (Brennan et al., 2006). Several studies have established that large gifts can have an influence on prescribing patterns (Orlowski and Wateska, 1992; Dieperink and Drogemuller, 2001). Controversy still rages about whether a small gift, such as a pen, influences prescribing behavior. For example, Steinman et al. (2001) and Halperin et al. (2004) argue that such small gifts are inconsequential. In contrast, Wazana (2000) argues that even a small gift may have an influence on behavior, while Dana and Loewenstein (2003, pg. 252) state that “by subtly affecting the way the receiver evaluates claims made by the gift giver, small gifts may be surprisingly influential.”

Some studies have argued that patient displays of knowledge can have a positive impact on physician practice styles and improve health (Hollon et al., 2003; Weissman et al., 2003). Others have argued that they erode the authority of physicians(Maguire, 1999; Kravitz, 2000; Jagsi, 2007), or have other negative effects (Mintzes et al., 2003; Kravitz et al., 2005).

In versions of the experiment in which more than one patient saw the same physician, we also tried clustering on the physician. The results are very similar whether we cluster on the hospital, cluster on the physician, or do not cluster.

We also estimated models with the patient’s sex and age, and the physician’s sex and estimated age (based on the patient’s assessment of the physician’s age). Results were virtually identical to those shown below.

This age variable is based on the patient’s assessment of the physician’s age.

Physicians also sometimes counseled patients to wear warm cloths, eat more fruit, or to avoid strenuous activity. We also coded this variable 1 if the physician offered any of this advice.

Physicians sometimes counseled patients to drink more water, get more rest, wear warm cloths, eat more fruit, or to avoid strenuous activity. We coded this variable 1 if the physician offered any of this advice.

We thank Fangwen Lu and the participants at the International Health Economic Association 2013 for their helpful comments. All errors are ours. Lin acknowledges research support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 70903003 and No. 71073002) and Humanities and Social Science Foundation from China Ministry of Education (Project No. 13YJA790064). Meng acknowledges research support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71103003).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Janet Currie, Princeton University.

Wanchuan Lin, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University.

Juanjuan Meng, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University.

REFERENCES

- Brennan Troyen A, Rothman David J, Blank Linda, Blumenthal David, Chimonas Susan C, Cohen Jordan J, Goldman Janlori, Kassirer Jerome P, Kimball Harry, Naughton James, Smelser Neil. Health Industry Practices that Create Conflicts of Interest. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:429–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Daniel Che-Lun Hung, Lauderdale Tsai-Ling. forthcoming. Health Care Competition and Antibiotic Use in Taiwan. Journal of Industrial Economics [Google Scholar]

- Camerer Colin. Gifts as Economic Signals and Social Symbols. American Sociological Review. 1988;94:180–214. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael H Lorne, MacLeod W Bentley. Gift Giving and the Evolution of Cooperation. International Economic Review. 1997;38:485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Cars Håkan, Håkansson Anders. To Prescribe-or not to Prescribe-Antibiotics: District Physicians’ Habits Vary Greatly, and are Difficult to Change. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 1995;13:3–7. doi: 10.3109/02813439508996727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Wang, Tang Shenglan, Sun Jing, Ross-Degnan Dennis, Wagner Anita K. Availability and Use of Essential Medicines in China: Manufacturing, Supply, and Prescribing in Shandong and Gansu Provinces. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10(1):211–218. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Wei, Fang Yunyun, Fan Dehui, Sun Jing, Shi Xuefeng, Li Jiao. The Effect of Implementing “Medicines Zero Mark-up Policy” in Beijing Community Health Facilities. Southern Med Review. 2012;5(1):53–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, Lin Wanchuan, Zhang Wei. Patient Knowledge and Antibiotic Abuse: Evidence from an Audit Study in China. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30:933–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, Lin Wanchuan, Meng Juanjuan. Social Networks and Externalities from Gift Exchange: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Journal of Public Economics. 2013;107:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Honglei, Fang Lizheng, Malouin Rebecca A, Huang Lijuan, Yokosawa Kenneth E, Liu Guozhen. Family Medicine Training in China. Family Medicine. 2013;45(5):341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana Jason, Loewenstein George. A Social Science Perspective on Gifts to Physicians from Industry. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:252–255. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar-Odeh Najla Saeed, Abu-Hammad Osama Abdalla, Al-Omiri, Khaled Mahmoud, Khraisat, Sameh Ameen, Shehabi Ata Asem. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices by Dentists: a Review. Therapeutics and Clinic Risk Management. 2010;6:301–306. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s9736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Jishnu, Holla Alaka, Das Veena, Mohanan Manoj, Tabak Diana, Chan Brian. In Urban and Rural India, a Standardized Patient Study Showed Low Levels of Provider Training and Huge Quality Gaps. Health Affairs. 2012;31(12):2774–2784. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieperink Michael E, Drogemuller, Drogemuller Lisa. Industry-Sponsored Grand Rounds and Prescribing Behavior. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1443–1444. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston Karen, Li Ling, Meng Qingyue, Magnus Lindelow, Adam Wagstaff. Health Service Delivery in China: A Literature Review. Health Economics. 2008;17(2):149–165. doi: 10.1002/hec.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston Karen, Yip Winnie. Hospital Competition under Regulated Prices: Application to Urban Health Sector Reforms in China. International Journal of Healthcare Finance and Economics. 2004;4(4):343–368. doi: 10.1023/B:IHFE.0000043762.33274.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Yu, Yang Shimin, Zhou Siting, Jiang Minghuan, Liu Jun. Community Pharmacy Practice in China: Past, Present and Future. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2013;35(4):520–528. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9789-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Minghai, Chu Wengong, Wang Dashui. Analysis on the Advantages and Disadvantages of the Hospital Pharmacy Trusteeship. Journal of Pharmaceutical Practice. 2012;30(01):67–77. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin Edward C, Hutchison Paul, Barrier Robert C. A Population-Based Study of the Prevalence and Influence of Gifts to Radiation Oncologists from Pharmaceutical Companies and Medical Equipment Manufacturers. Journal of Radiation Oncology. 2004;59:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman James, Siegelman Peter. The Urban Institute Audit Studies: Their Methods and Findings. In: Fix M, Struyk R, editors. Clear and Convincing Evidence: Measurement of Discrimination in America. Lanham, MD: Urban Institute Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hollon MF, Larson EB, Koepsell TD, Downer AE. Direct-to-Consumer Marketing of Osteoporosis Drugs and Bone Densitometry. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2003;37(7):976–981. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao William C. In: Containing Health Care Costs in Japan. Ikegami Naoki, Campbell, John Campbell., editors. Michigan: University of Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao William C, Liu Yuanli. Economic Reform and Health—Lessons from China. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:430–432. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608083350611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Ying, Gu Jiarui, Zhang Mingyu, Ren Zheng, Yang Weidong, Chen Yang, Fu Yingmei, Chen Xiaobei, Cals Jochen WL, Zhang Fengmin. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Antibiotics: a Questionnaire Study among 2500 Chinese Students. BMC Medical Education. 2013;13:163. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Toshiaki. Experts’ Agency Problems: Evidence from the Prescription Drug Market in Japan. RAND Journal of Economics. 2007;38:844–862. doi: 10.1111/j.0741-6261.2007.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Toshiaki. Physician Agency and Adoption of Generic Pharmaceuticals. American Economic Review. 2012;102(6):2826–2858. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.6.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagsi Reshma. Conflicts of Interest and the Physician-Patient Relationship in the Era of Direct-to-Patient Advertising. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(7):902–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.7122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz Richard L. Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs: Implications for the Patient-Physician Relationship. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(17):2240–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz Richard L, Epstein Ronald M, Feldman Mitchell D, Franz Carol E, Azari Rahman, Wilkes Michael S, Hinton Ladson, Franks Peter. Influence of Patients’ Requests for Directly Advertised Antidepressants: a Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Yongbin, Xu Jing, Wang Fang, Wang Bin, Liu Liqun, Hou Wanli, Fan Hong, Tong Yeqing, Zhang Juan, Lu Zuxun. Overprescribing in China, Driven by Financial Incentives, Results in Very High Use of Antibiotics, Injections, and Corticosteroids. Health Affairs. 2012;31(5):1075–1082. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xingzhu, Liu Yuanli, Chen Ningshan. The Chinese Experience of Hospital Price Regulation. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15:157–163. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]