Cockroach-inspired robots navigate crawlspaces

American cockroach traversing a crevice. Image credit: Image courtesy of the PolyPEDAL Lab (University of California, Berkeley, CA).

Cockroaches can infest virtually any space by exploiting rigid, jointed exoskeletons to slip through seemingly impassable crevices. To quantify the limits of this ability, Kaushik Jayaram and Robert Full (pp. E950–E957) constructed an obstacle course for the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana). The authors found that P. americana can slip through a space smaller than a quarter of its standing body height in less than 1 second by compressing its exoskeleton to around half its original size. Also, these insects continue to move rapidly in confined spaces, at speeds of approximately 20 body lengths per second. Next, the authors altered the friction of the ceiling and ground and determined that cockroaches run in confined spaces using a previously unreported mode of locomotion dubbed body-friction legged crawling. The authors’ material tests show that cockroaches can withstand forces of around 300 times their own body weight when slipping through extremely narrow spaces and can withstand nearly 900 times their own body weight without injury. Inspired by P. americana, the authors built a palm-sized, soft-legged robot that can compress itself by more than half to negotiate confined spaces, aided by a low-friction shell. According to the authors, cockroaches represent a suitable model for insect-inspired robots that can navigate challenging spaces, such as rubble piles in disaster zones. — T.J.

Competition and extinction of Neanderthals

Reconstruction of Neanderthal man at the Neanderthal Museum in Germany. Image courtesy of Flickr/Erich Ferdinand.

Archaeologists have hypothesized that competition between Neanderthals and modern humans led to the former’s extinction, likely because of the competitive edge afforded by modern humans’ advanced culture. William Gilpin et al. (pp. 2134–2139) tested the plausibility of this hypothesis using a model of interspecies competition that incorporates differences in the competing species’ levels of cultural development. According to the model, an initially small modern human population could completely displace a larger Neanderthal population, provided that the modern humans had a sufficiently large cultural advantage over the Neanderthals. The minimum modern human population that could displace the Neanderthals decreased with increasing cultural advantage and with a decrease in the rate of cultural change relative to population growth. This minimum population threshold also decreased when the authors introduced a positive feedback loop into the model, such that increasing the size of modern humans’ cultural advantage increased the size of their competitive advantage, which in turn further increased their cultural advantage. The results support the hypothesis that competition with modern humans drove Neanderthals to extinction, likely due to competitive advantages tied to levels of cultural development, according to the authors. — B.D.

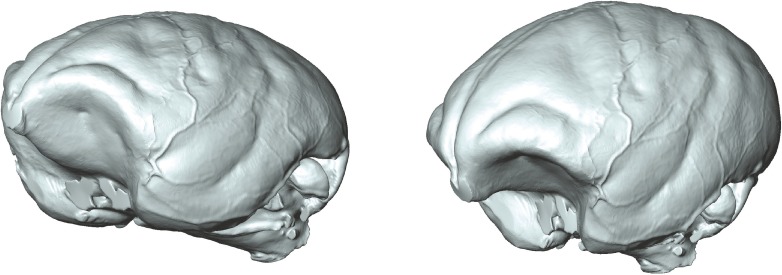

Brain shape evolution in New World monkeys

Brain shape variation in New World monkey species.

Brain shape diversification over the course of evolution is an important feature of primate adaptive radiation. Large brains are a significant trait of Homo sapiens, and the relative sizes of different parts of the brain in different species may be more important than total relative brain size in terms of brain evolution. However, the conditions under which the diversification of brain shape occurs remain unclear. Leandro Aristide et al. (pp. 2158–2163) investigated the role of ecological factors such as group size, diet composition, and locomotion strategy in the process of primate brain shape diversification. The authors used a sample of 179 adult skulls from a group of New World monkeys called platyrrhines. The sample included both sexes of 49 platyrrhine species belonging to 17 genera. Brain shape variation was quantified via virtual reconstruction and analyzed using evolutionary models. The results suggest the existence of separate bursts of brain evolution over the course of platyrrhine radiation, with brain shape convergence likely occurring at a late stage following earlier diversification. In particular, the relative enlargement of the neocortex that occurred in multiple groups may have evolved in response to the cognitive demands of life in increasingly large, complex social groups, according to the authors. — L.G.

Recording whole-brain activity in moving animals

The ability to use sensory information from the environment to decide which movements to make is critical for survival. To fully understand this complex process, brainwide neural activity must be monitored as an animal responds to environmental changes. Vivek Venkatachalam et al. (pp. E1082–E1088) developed an imaging setup and analysis pipeline to track and simultaneously record the activity of approximately 80 neurons at single-cell resolution in crawling nematodes exposed to fluctuating environmental conditions. The authors used genetic techniques to make neurons in the nematode brain emit fluorescence when activated, and then built a customized microscope to continuously track the movements of crawling nematodes and record neural activity across the brain. Image analysis algorithms filtered out motion artifacts from the animals’ movements and identified individual neurons based on unique, local patterns of fluorescent signals from constellations of nearby neurons. Using this imaging pipeline, the authors identified specific sensory and motor neurons whose activities were modulated by the nematodes’ forward and backward movements in response to temperature fluctuations. According to the authors, the imaging system could be used in transparent, moving animals to uncover insights into the neural circuits that transform sensory information into behavioral decisions. — J.W.

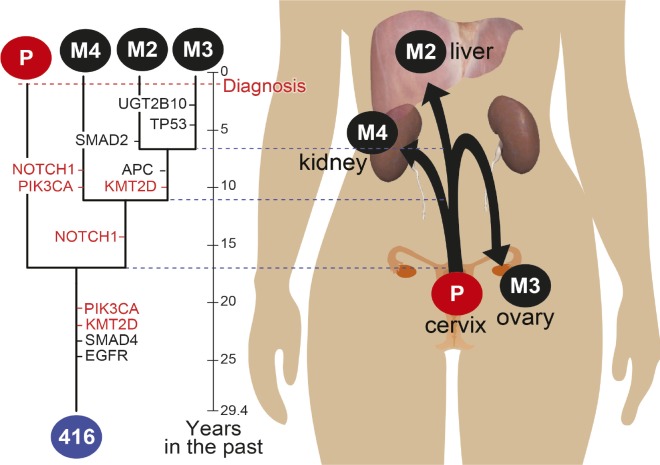

Evolutionary analysis of origin of cancer metastases

Evolutionary analysis can help uncover origin of metastatic lineages. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Mikael Häggström.

Many aspects of tumor formation remain poorly understood, including the origins of metastatic lineages. To study how metastases arise, Zi-Ming Zhao et al. (pp. 2140–2145) used evolutionary biology tools to analyze exome sequences from 32 primary tumors and 139 metastatic sites from 40 volunteers. The authors’ analysis supported a nonlinear model of cancer progression, in which metastatic tumors originate from divergent lineages within primary tumors rather than descending from a single departing primary tumor cell. The authors examined the timing of gene mutations and how the mutations contributed to tumor formation. The results suggest that a specific series of genetic changes are unlikely to be required to give rise to metastases, with heritable genetic and epigenetic events that occur early in tumor evolution likely only affecting the tendency toward metastasis. In addition, the authors found that metastatic lineages are produced stochastically and arise early in tumor development, sometimes well before diagnosis of the primary tumor. The analyses could help elucidate the timing of mutations in driver genes that occur early in cancer evolution. According to the authors, these mutations could serve as therapeutic targets against both primary tumors and metastases. — S.R.

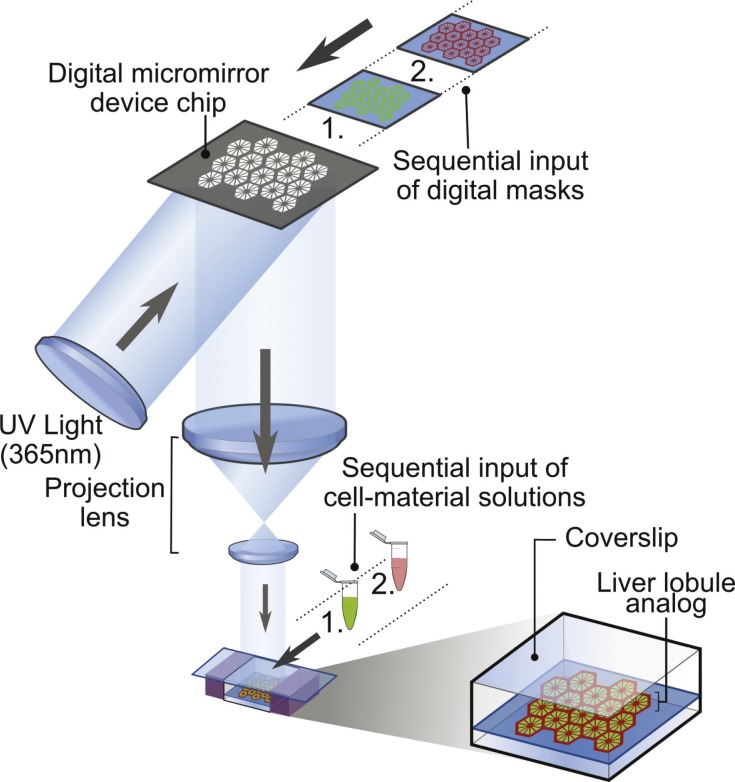

3D model of human liver

Schematic of 3D bioprinting of a hydrogel-based hepatic construct.

In vitro models of the liver fail to precisely recapitulate the complex structures of hepatic lobules, which consist of diverse cell types in which hepatocytes develop and function. However, the development of light-assisted 3D bioprinting has enabled the design of digital masks that allow distinct cell types to be assembled in precise tissue architecture. Xuanyi Ma et al. (pp. 2206–2211) used such a method to build a 3D triculture model of the human liver in which hepatic progenitor cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) are localized to hexagonal lobules within a photopolymerizable gel matrix using one mask, followed by localization of two types of supporting cells to the surrounding spaces using a second mask. The hiPSC-derived hepatic progenitor cells (hiPSC-HPCs) grown in 3D triculture expressed hepatic markers at higher levels than those grown in either 2D triculture or 3D hiPSC-HPC monoculture, suggesting that 3D triculture enabled greater hepatocyte maturation than the two other methods. Cells grown in 3D triculture also secreted relatively greater amounts of albumin and urea and expressed higher levels of key cytochrome P450 enzymes, which metabolize drugs in the liver. According to the authors, the triculture model has potential applications for personalized medicine, drug screening, and translational studies. — C.B.