Significance

Long-term potentiation (LTP), a form of synaptic plasticity that results in the strengthening of glutamatergic synapses, is believed to be the cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory. LTP is induced by calcium influx through NMDA receptors, which in turn activates CaMKII; however, the substrates that CaMKII phosphorylate that ultimately give rise to LTP have been the subject of debate for more than two decades. Here we show that the RhoGEF proteins Kalirin and Trio are the substrates of CaMKII responsible for LTP induction. Furthermore, we show that glutamatergic synapses require Kalirin and Trio, given that such synapses no longer exist in the absence of these proteins.

Keywords: Kalirin, Trio, LTP, CaMKII, spines

Abstract

The molecular mechanism underlying long-term potentiation (LTP) is critical for understanding learning and memory. CaMKII, a key kinase involved in LTP, is both necessary and sufficient for LTP induction. However, how CaMKII gives rise to LTP is currently unknown. Recent studies suggest that Rho GTPases are necessary for LTP. Rho GTPases are activated by Rho guanine exchange factors (RhoGEFs), but the RhoGEF(s) required for LTP also remain unknown. Here, using a combination of molecular, electrophysiological, and imaging techniques, we show that the RhoGEF Kalirin and its paralog Trio play critical and redundant roles in excitatory synapse structure and function. Furthermore, we show that CaMKII phosphorylation of Kalirin is sufficient to enhance synaptic AMPA receptor expression, and that preventing CaMKII signaling through Kalirin and Trio prevents LTP induction. Thus, our data identify Kalirin and Trio as the elusive targets of CaMKII phosphorylation responsible for AMPA receptor up-regulation during LTP.

One of the most remarkable properties of the brain is its ability to store vast amounts of information. It is now widely accepted that this storage involves the rapid enhancement of synaptic strength, which can persist for prolonged periods. This phenomenon, known as long-term potentiation (LTP), has been observed at numerous glutamatergic excitatory synapses throughout the brain. At hippocampal CA1 synapses, LTP is expressed as a rapid increase in the number of postsynaptic AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs) following the coincident activation of presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons (1–4). This form of LTP is dependent on the activation of NMDA-type glutamate receptors (NMDARs), which transiently elevate spine calcium. This calcium influx activates calcium-calmodulin–dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Although CaMKII activation has been shown to be both necessary and sufficient for LTP (5), the critical downstream targets of CaMKII have yet to be identified.

One possible target of CaMKII during LTP is the family of neuronal Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEFs). RhoGEFs catalyze GDP/GTP exchange on small Rho guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (Rho GTPases), which in turn regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Previous studies have shown that the Rho GTPase Rac1 regulates synaptic AMPAR expression (6), and that the Rho GTPases Cdc42 and RhoA are required for LTP and the structural enlargement of spines that accompanies LTP (i.e., sLTP) (7, 8); however, which RhoGEFs are responsible for synaptic Rho GTPase activation and whether RhoGEF regulation is involved in the changes in synaptic function that occur during LTP remain unknown.

Most studies reported to date have focused on the RhoGEF Kalirin. Alternative splicing of a single Kalirin gene results in the expression of several Kalirin isoforms. Previous work has shown that the Kalirin isoform Kalirin-7 is enriched in spines, is involved in synaptic maintenance, and is phosphorylated by CaMKII, and that Kalirin-7 overexpression (OE) in dissociated cortical neurons results in increased spine size (9). Such data support a role for Kalirin proteins in the structural changes in spines that accompany LTP; however, LTP in the hippocampus is largely normal in Kalirin KO mice, in which all Kalirin proteins resulting from the single Kalirin gene have been eliminated (10), and thus Kalirin proteins cannot be solely responsible for LTP. One possible explanation is that Kalirin supports LTP along with a functionally redundant, as-yet unidentified RhoGEF protein.

Here we used molecular, imaging, and electrophysiological approaches to evaluate the contributions of RhoGEFs to excitatory synapse structure, function, and plasticity in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Our findings demonstrate, for the first time to our knowledge, that the Kalirin paralog Trio plays an important role in postsynaptic function, and that Trio and Kalirin serve critical and functionally redundant roles in supporting excitatory synapse structure and function in CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus. We also report that although inhibiting Kalirin function alone has no effect on LTP, simultaneously inhibiting CaMKII signaling through Kalirin and Trio eliminates LTP induction. Furthermore, phosphorylation of Kalirin-7 by CaMKII is sufficient to enhance synaptic AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that NMDAR-mediated activation of CaMKII induces functional LTP through phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio, which then give rise to the synaptic changes underlying synaptic AMPAR up-regulation.

Results

Initially, in an effort to understand how enhancing Kalirin function influences CA1 pyramidal neurons, we increased Kalirin expression in these neurons. We did this using biolistic transfection to overexpress the primary hippocampal isoform of Kalirin, Kalirin-7 (Kal-7), in CA1 pyramidal neurons of organotypic rat hippocampal slice cultures. At 6–7 d after transfection, we analyzed the size of dendritic spines and found that Kal-7 OE resulted in a significant increase in spine size (Fig. S1A), as previously reported in dissociated cortical neurons (9).

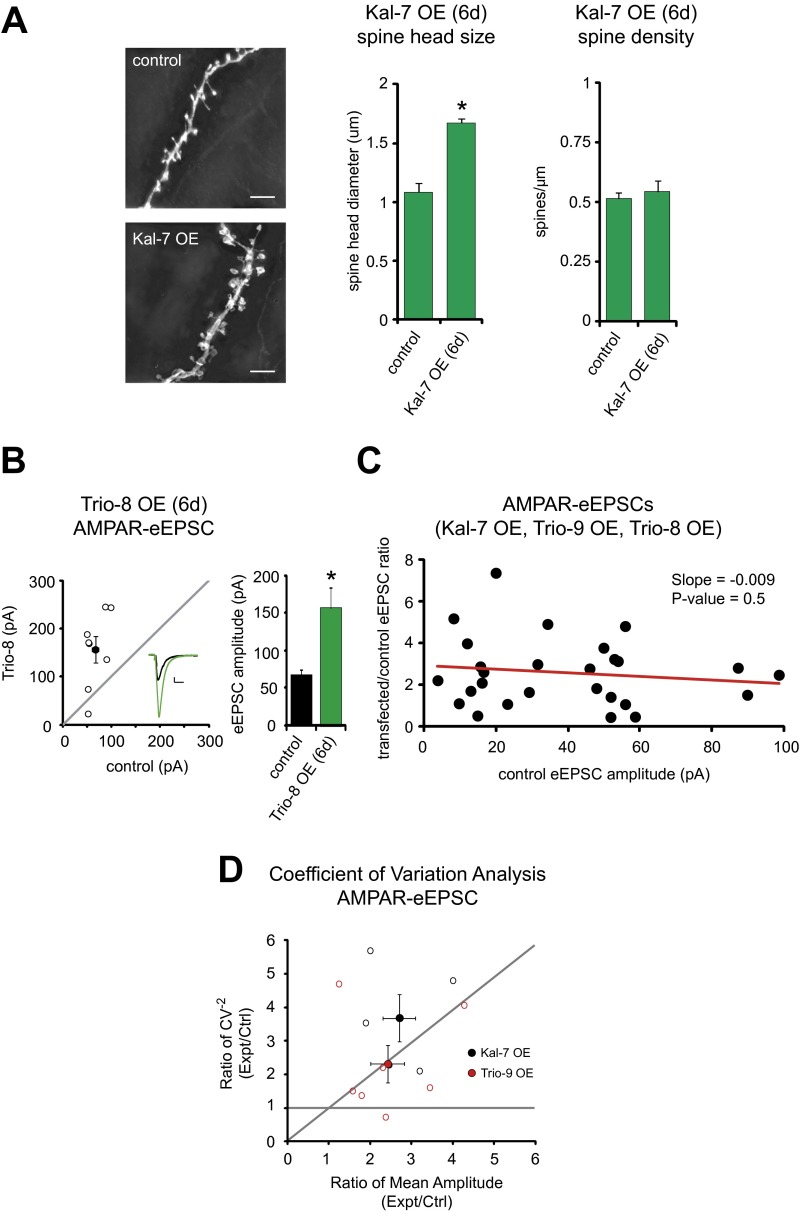

Fig. S1.

Kalirin/Trio OE: effects on spine morphology, phenotype dependence on stimulation strength, and effects on quantal content. (A) Bar graphs showing mean ± SEM spine head diameter (Left) and spine density (Right) of control and Kal-7 OE CA1 pyramidal neurons (control, n = 6 neurons; Kal-7 OE, n = 6 neurons; *P = 0.005). Representative images of dendritic spines of control and Kal-7 OE CA1 pyramidal neurons are shown on the left. (Scale bars: 5 μm.) (B) Scatterplot showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and Trio-8 transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. The bar graph shows mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude for control and Trio-8 OE neurons (n = 8 pairs; *P = 0.01). (Inset) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms, 20 pA.) (C) Scatterplot showing transfected/control AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude ratio vs. control AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude for single pairs of control and Kal-7, Trio-9, or Trio-8 transfected neurons. Linear regression analysis was performed on the data (red line). (D) Coefficient of variation analysis of simultaneously recorded pairs of control/Kal-7 OE and control/Trio-9 OE neurons (open circles). CV−2 is graphed against the ratio of mean amplitude within each pair. Results along the horizontal line are consistent with changes in quantal size (q); results along the identity (45°) line are consistent with changes in quantal content (N × Pr). Analysis of AMPAR responses indicates that the increase in amplitude produced by Kal-7 and Trio-9 is due to an increase in quantal content (Kal-7 OE, n = 5 pairs; Trio-9, n = 7 pairs).

We then made recordings of AMPAR- and NMDAR-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs, respectively) from fluorescent transfected neurons overexpressing Kal-7 and neighboring untransfected control neurons simultaneously during stimulation of Schaffer collaterals. This approach permitted a pairwise, internally controlled comparison of the consequences of the genetic manipulation. Interestingly, we found that Kal-7 OE for 6 d in CA1 pyramidal neurons produced a nearly threefold increase in AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. 1 B and E). This enhancement was selective for AMPAR-eEPSCs, in that no change in NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude was observed (Fig. 1 B and E).

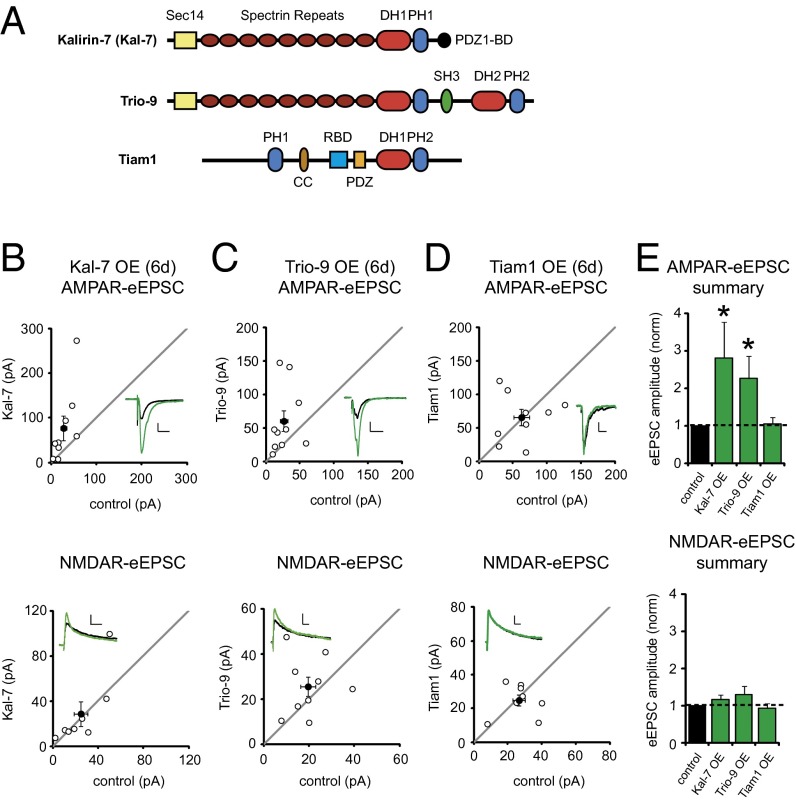

Fig. 1.

Kal-7 and Trio-9 OE enhance AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. (A) Illustration of Kal-7, Trio-9, and Tiam1 protein domains. CC, coiled-coil domain; DH, Dbl homology domain; PDZ1-BD, type I PDZ-binding domain; PDZ, PDZ domain; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; RBD, Ras binding domain; Sec14, Sec14 homology domain; SH3, SRC homology 3 domain. (B–D) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (B) Kal-7 OE for 6 d increased AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 9 pairs; *P = 0.02), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 8 pairs). (C) Trio-9 OE for 6 d increased AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 10 pairs; *P = 0.03), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 9 pairs). (D) Tiam1 OE for 6 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 9 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 8 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) (E) Bar graphs normalized to control summarizing the mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in B–D.

Next, in an effort to identify an additional RhoGEF protein that may have a function similar to Kalirin, we initially selected Kalirin’s paralog Trio. Trio is found in numerous brain regions, is synaptically expressed in hippocampal neurons, and at the amino acid level has a high level of sequence homology to Kalirin (11). Specifically, we chose Trio’s most abundant isoform in the hippocampus, Trio-9 (Fig. 1A) (12, 13). When we overexpressed Trio-9, we found that this produced an increase in synaptic AMPAR expression nearly identical to that seen with Kal-7 (Fig. 1 C and E). Increases in AMPAR current amplitude produced by Kalirin and Trio were independent of Schaffer collateral stimulation intensity (Fig. S1 B and C) and, like LTP (14), resulted from increases in quantal content, presumably due to the unsilencing of synapses (Fig. S1D).

We then examined the effects of overexpressing Tiam1, a RhoGEF that, like Kalirin, is phosphorylated by CaMKII and has been previously implicated in the structure of hippocampal synapses (15, 16) (Fig. 1A). Tiam1 OE produced no effect on AMPAR- or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. 1 D and E) and was not studied further. Taken together, the foregoing data demonstrate that Kalirin and Trio influence synaptic transmission in a similar manner that is not common to all RhoGEFs.

Given that Kal-7 and Trio-9 behave similarly when overexpressed, we wanted to know whether endogenous Kalirin and Trio proteins play similar roles in synaptic transmission. To test this, we used an miRNA construct targeting the primary hippocampal isoforms of Kalirin (Kal-miR) and an shRNA construct targeting the primary hippocampal isoforms of Trio (Trio-shRNA), and performed Western blot and RT-PCR analyses to confirm RNAi effectiveness (Fig. S2 A–C). We then knocked down Kalirin expression for 6 d in CA1 pyramidal neurons, and found that this reduced AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude by ∼60% and NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude by ∼30% (Fig. 2 A and D). Expression of Kal-miR in CA1 pyramidal neurons from Kalirin KO mice (10) failed to affect glutamatergic transmission, demonstrating that this RNAi lacks off-target effects (Fig. S2D). We then knocked down Trio expression in WT CA1 pyramidal neurons for 6 d and found a reduction in AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude nearly identical to that produced by knockdown of Kalirin (Fig. 2 B and D). NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude, although modestly reduced, was not significantly affected. Taken together, these results demonstrate for the first time, to our knowledge, that these highly homologous RhoGEFs play similar roles in supporting normal hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission.

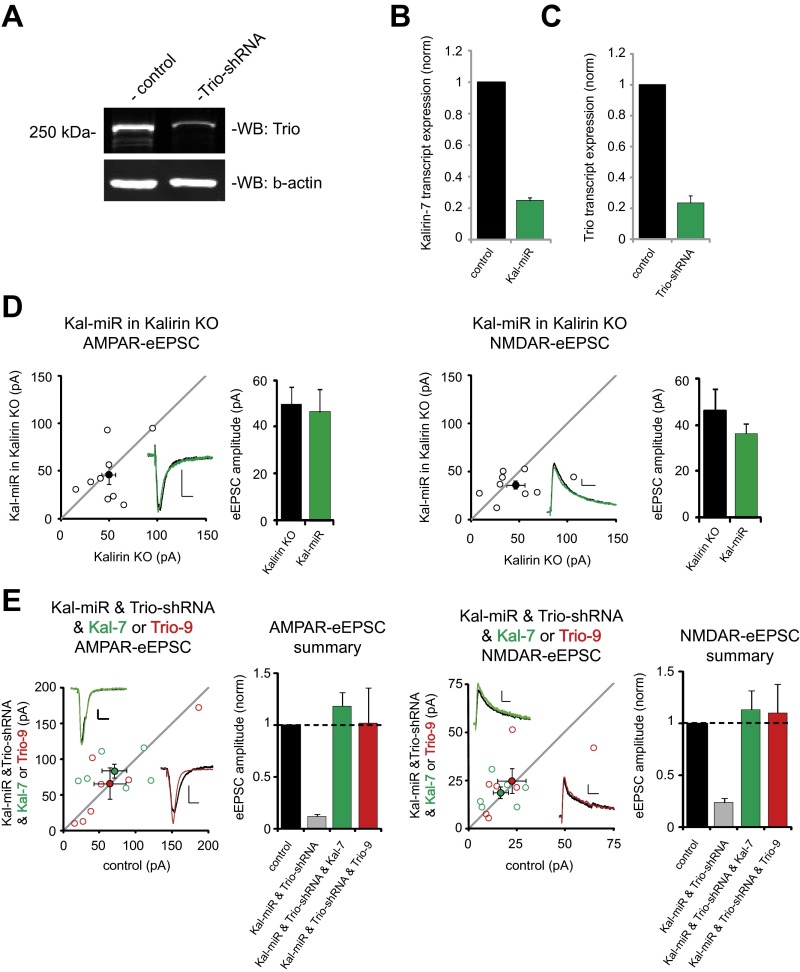

Fig. S2.

Characterization of Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA constructs. (A) Western blot showing Trio-shRNA–mediated reduction of Trio expression in HEK cells. (B) Bar graph showing mean ± SEM percent of Kal-7 mRNA remaining after Kal-miR expression in hippocampal neurons normalized to control (Kal-miR, 25 ± 2%; n = 2). (C) Bar graph showing mean ± SEM percent of Trio mRNA remaining after Trio-shRNA expression in hippocampal neurons normalized to control (Trio-shRNA, 24 ± 4%; n = 2). (D and E) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (D) Kal-miR expression in Kalirin KO mice does not affect AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Left; n = 9 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Right; n = 9 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data. (E) Coexpression of Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA with Kal-7 or Trio-9 has no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Left: Kal-miR, Trio-shRNA, and Kal-7, n = 6 pairs; Kal-miR, Trio-shRNA, and Trio-9, n = 7 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Right: Kal-7, n = 6 pairs; Trio-9, n = 7 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from a control neuron (black); a Kal-miR, Trio-shRNA, and Kal-7 cotransfected neuron (green); and a Kal-miR, Trio-shRNA, and Trio-9 cotransfected (red) neuron. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) The bar graphs to the right of the scatterplots are normalized to control comparing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in E with that shown in Fig. 2C (gray bar).

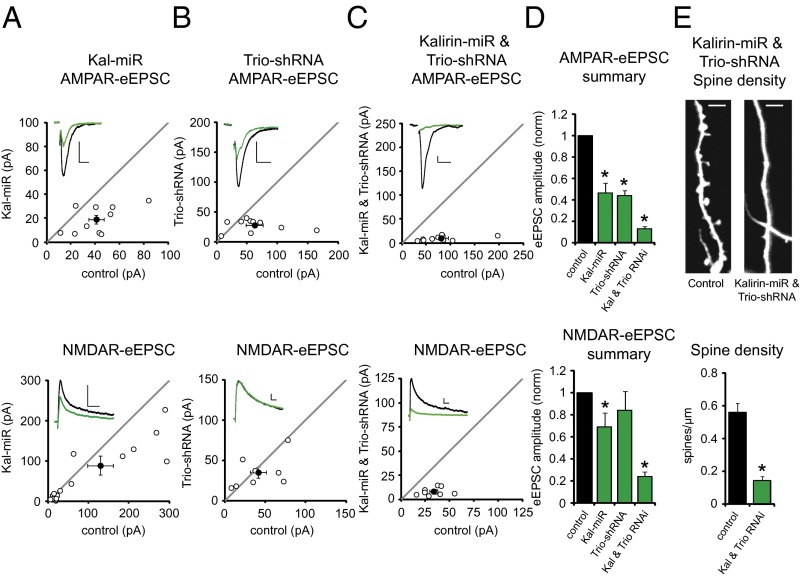

Fig. 2.

Excitatory synapses require Kalirin and Trio expression. (A–C) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (A) Distributions showing that Kal-miR reduced AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 10 pairs; *P = 0.01) and NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 20 pairs; *P = 0.001). (B) Trio-shRNA reduced AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 10 pairs; *P = 0.02), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 8 pairs). (C) Coexpression of Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA reduced AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 10 pairs; *P = 0.002) and NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 9 pairs; *P = 0.01). (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) (D) Bar graphs normalized to control summarizing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in A–C. (E, Upper) Representative images of dendrites from control neurons and neurons transfected with Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA. (Scale bars: 3 µm.) (Lower) Spine density was significantly reduced by simultaneous knockdown of Kalirin and Trio proteins (control, n = 8 neurons; Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA, n = 11 neurons; *P < 0.001).

Given that Kalirin and Trio are highly homologous proteins, it stands to reason that they may serve overlapping functions in supporting synaptic transmission. Thus, the expression of one may mitigate the effects of losing the other. To address this question, we simultaneously expressed Kal-miR and Trio-shRNA in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Remarkably, we found that knocking down both Kalirin and Trio expression nearly eliminated AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs, indicating that these two proteins are critical for synaptic function (Fig. 2 C and D). This deficit in synaptic transmission was completely rescued by expression of either a Kal-miR–resistant form of Kal-7 or a Trio-shRNA–resistant form of Trio-9 (Fig. S2E). Therefore, we conclude that Kalirin and Trio are functionally redundant proteins that together play a fundamental role in the function of excitatory synapses.

What could account for this loss of synaptic strength? The fact that the AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs are reduced to roughly the same extent suggests that the loss could be due to a loss of synapses. To address this possibility, we examined dendritic spine density, considering that most excitatory synapses are formed on spines. There was an ∼80% loss of spines (Fig. 2E), which correlated well with the functional loss. Thus, our results suggest that Kalirin and Trio proteins together support a level of actin polymerization within spines critical for both the structure and function of excitatory synapses.

We then wanted to know how these RhoGEFs enhance AMPAR expression at excitatory synapses. We find that Kal-7 and Trio-9 are functionally redundant proteins with conserved regions being ∼80% identical at the amino acid level. Given that previous studies provide a framework for studying Kal-7, we chose to use Kal-7 as a representative of these two proteins in our experiments examining Kal-7/Trio-9–mediated increases in AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude. Previous work has shown that synaptic activity leads to activation of Rho GTPases through unidentified RhoGEFs (7). To determine whether Kal-7’s ability to increase synaptic AMPAR expression is dependent on synaptic activity, we overexpressed Kal-7 in hippocampal slices cultured in medium containing AP5 to block NMDARs and NBQX to block AMPARs. We found that preventing synaptic activity during Kal-7 OE blocked the ability of Kal-7 to increase AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. 3 A and E).

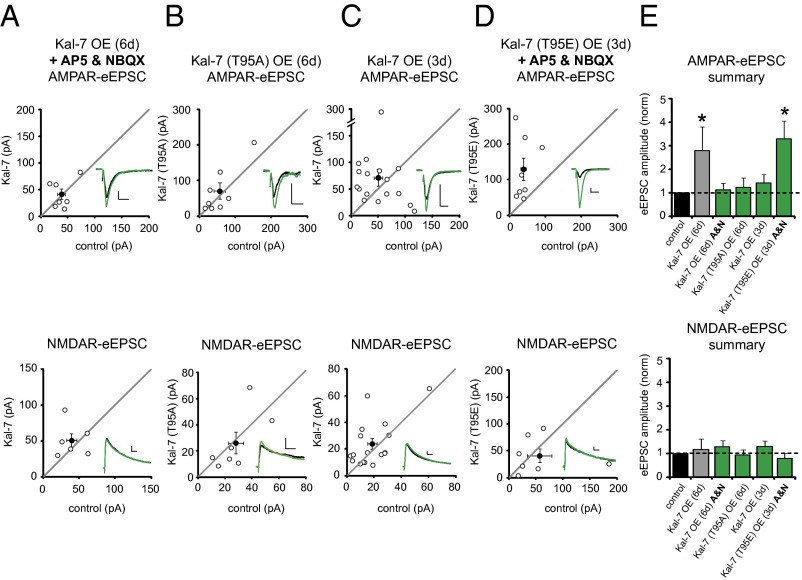

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of Kal-7 T95 is sufficient to enhance synaptic AMPAR function. (A–D) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (A) Distributions showing that Kal-7 OE for 6 d in neurons cultured in AP5 and NBQX (A&N) had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 7 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 6 pairs). (B) Kal-7 (T95A) OE for 6 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 8 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 7 pairs). (C) Kal-7 OE for 3 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 17 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 17 pairs). (D) Kal-7 (T95E) OE for 3 d in neurons cultured in AP5 and NBQX (A&N) increased AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 8 pairs; *P = 0.01), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 7 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) (E) Bar graphs normalized to control comparing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in A–D with that shown in Fig. 1B (gray bar).

Previous work has shown that CaMKII phosphorylates Kal-7 on amino acid T95 (9); therefore, we asked whether preventing CaMKII phosphorylation of this site would prevent Kal-7–mediated synaptic enhancement. Indeed, substituting this threonine with an alanine (T95A) prevented Kal-7 from increasing AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. 3 B and E). We found that inhibiting CaMKII activation also blocked Kal-7’s ability to increase AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. S3). In addition, we found that Kal-7 OE for a shorter period of 3 d, rather than 6 d, did not result in a significant increase in AMPAR currents (Fig. 3 C and E). Thus, exposure of elevated levels of Kal-7 to synaptic activity over time may give rise to a progressive increase in Kal-7 T95 phosphorylation by CaMKII, leading to enhanced synaptic AMPAR transmission. In an effort to test this hypothesis, we overexpressed a mutant of Kal-7 mimicking T95 phosphorylation, Kal-7 (T95E), for 3 d in slices cultured in AP5 and NBQX. Remarkably, Kal-7 (T95E) increased AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude 3 d earlier than WT Kal-7, and did so in the absence of synaptic activity (Fig. 3 D and E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that phosphorylation of Kal-7 T95 is sufficient for enhancement of AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. We also found that Cdc42, a Rho GTPase recently implicated in LTP induction (7, 8), was also required for the action of Kal-7 to increase AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. S4); thus, Cdc42 may connect Kalirin activity to downstream pathways associated with LTP.

Fig. S3.

Kalirin-7 has CaMKII–independent and CaMKII-dependent levels of function. (A) Knockdown of endogenous Kalirin with Kal-miR and coexpressing recombinant Kal-7 resulted in selective enhancement of synaptic AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude similar to OE of Kal-7 alone (n = 10 pairs; *P = 0.01) (Fig. 1B). Thus, this manipulation results in the expression of recombinant Kal-7 above endogenous levels. (B) Coexpression of the CaMKII inhibitor (CKIIN) with Kal-miR and recombinant Kal-7 prevented the enhancement of AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude above baseline/control levels (n = 15 pairs). This result is consistent with the need for CaMKII activity for Kal-7-mediated enhancement of AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude above that of control cells and the ability of CaMKII-independent Kal-7 activity to rescue the Kal-miR phenotype up to control levels. (C) Bar graph, normalized to control, summarizing the mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC data in A and B compared with that in Fig 2A (gray bar). *P < 0.05. Because CKIIN alone has been shown to reduce baseline AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (33), it is possible that CaMKII inhibition of Kal-7’s ability to enhance AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude as shown in Fig. S3B is due to an unrelated mechanism. (D) Coexpression of Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) rescued the Kal-miR phenotype without enhancing AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude above that of control cells (n = 10 pairs). (E) On coexpression of Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) with CKIIN, blocking CaMKII activity did not prevent Kal-7 (T95A) from rescuing the Kalirin knockdown AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude phenotype to control levels (n = 10 pairs). (F) Bar graph normalized to control summarizing the mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC data in D and E compared with that shown in Fig. 2A (gray bar). These data demonstrate that that in the absence of CaMKII activity/T95 phosphorylation, recombinant Kal-7 retained a level of activity capable of rescuing the Kal-miR phenotype and supporting normal baseline AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that the block of Kal-7–mediated enhancement of AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude above baseline levels in Fig. S3A by CKIIN is due to a direct inhibition of CaMKII’s actions on Kal-7. Based on these data, we conclude that Kalirin (and Trio) have two functions: (i) CaMKII- and T95-independent support of basal glutamatergic neurotransmission through a baseline level of activity and (ii) CaMKII- and T95-dependent enhancement of synaptic AMPAR receptor expression above baseline levels. Scatterplots show amplitudes of AMPAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) (G) Bar graph showing mean ± SEM NMDAR-eEPSC amplitudes for manipulations performed in A (n = 8 pairs), B (n = 14 pairs), D (n = 15 pairs), and E (n = 8 pairs).

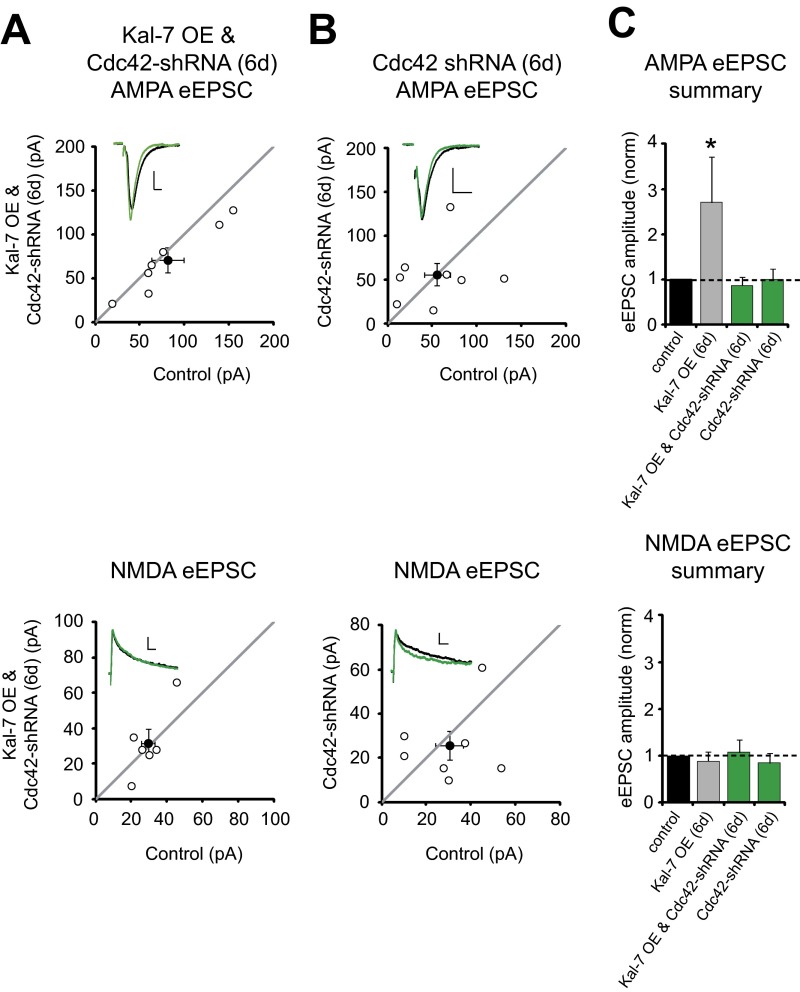

Fig. S4.

Kal-7 enhancement of synaptic AMPAR function requires Cdc42. (A and B) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs of control and transfected neurons in cultured hippocampal rat slices. Filled circles represent mean ± SEM. (A) Distributions showing that coexpression of Kal-7 and a Cdc42-shRNA for 6 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 7 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 6 pairs). (B) Expression of the Cdc42-shRNA for 6 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 8 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 7 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from a control neuron (black) and a transfected neuron (green). (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) (C) Bar graphs normalized to control comparing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in A and B with that shown in Fig. 1B (gray bar).

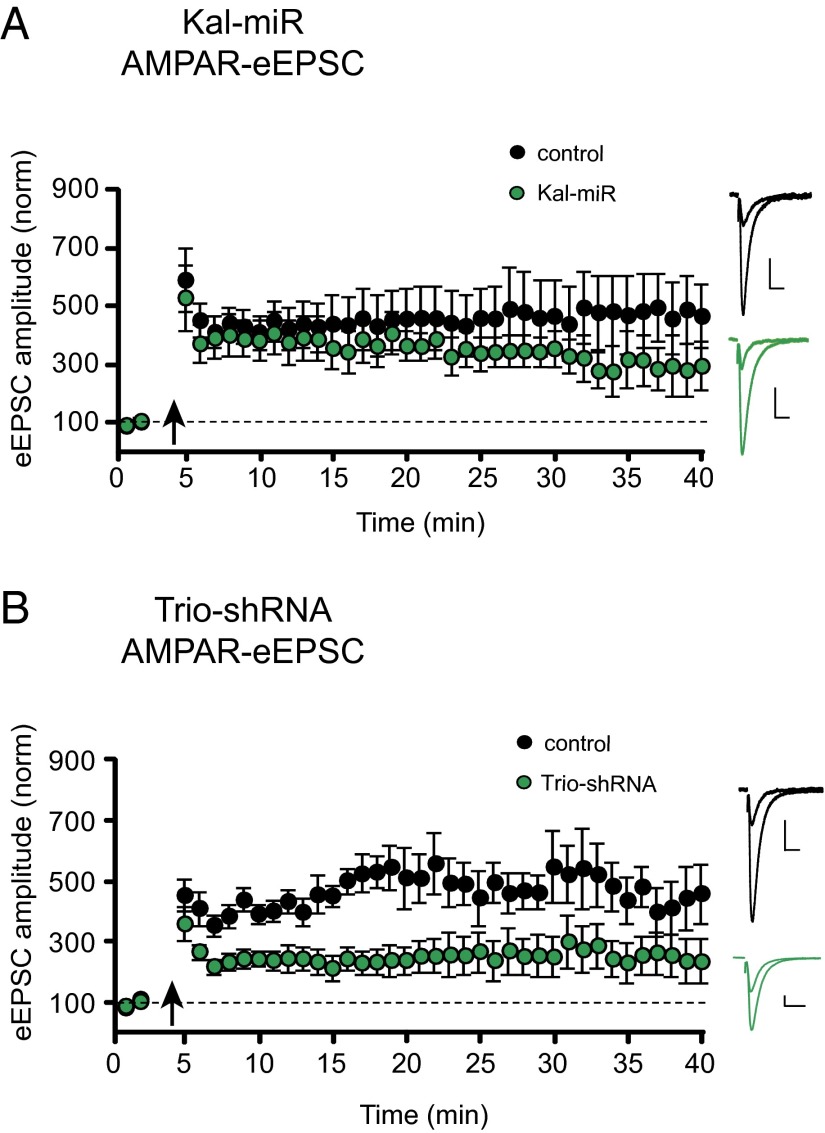

To explore whether Kalirin and Trio proteins contribute to LTP, we used in utero electroporation of embryonic day (E) 15 mice to express either Kal-miR or Trio-shRNA in hippocampal neurons and examined LTP in electroporated CA1 pyramidal neurons of postnatal day (P)17–P24 mice. We found that knockdown of Kalirin expression alone had little effect on LTP (Fig. 4A). This finding is consistent with a previous report (10), as well as with our own data demonstrating LTP in mice lacking all Kalirin isoforms (Fig. S5A). LTP was also observed in rat CA1 pyramidal cells following a more acute knockdown of Kalirin expression using a Kal-miR–expressing lentivirus (Fig. S5B). Knockdown of Trio expression, on the other hand, produced a moderate reduction of LTP (Fig. 4B). Of note, however, is that neither manipulation prevented LTP induction. Taken together, these data demonstrate that although Kalirin and Trio may be involved in LTP, neither is individually responsible for LTP induction.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of Kalirin or Trio expression does not prevent LTP induction. (A) Plots of mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude of control untransfected CA1 pyramidal neurons (black) and CA1 pyramidal neurons electroporated with Kal-miR (green) normalized to the mean AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude before an LTP induction protocol (arrow) (control, n = 9 neurons; Kal-miR, n = 7 neurons). (B) Plots of AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude of control untransfected CA1 pyramidal neurons (black) and CA1 pyramidal neurons electroporated with the Trio-shRNA (green) normalized to the mean AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude before an LTP induction protocol (arrow) (control, n = 8 neurons; Trio-shRNA, n = 8 neurons). Sample AMPAR-eEPSC current traces from control (black) and electroporated (green) neurons before and after LTP induction are shown to the right of the graphs. (Scale bars: 20 ms, 20 pA.)

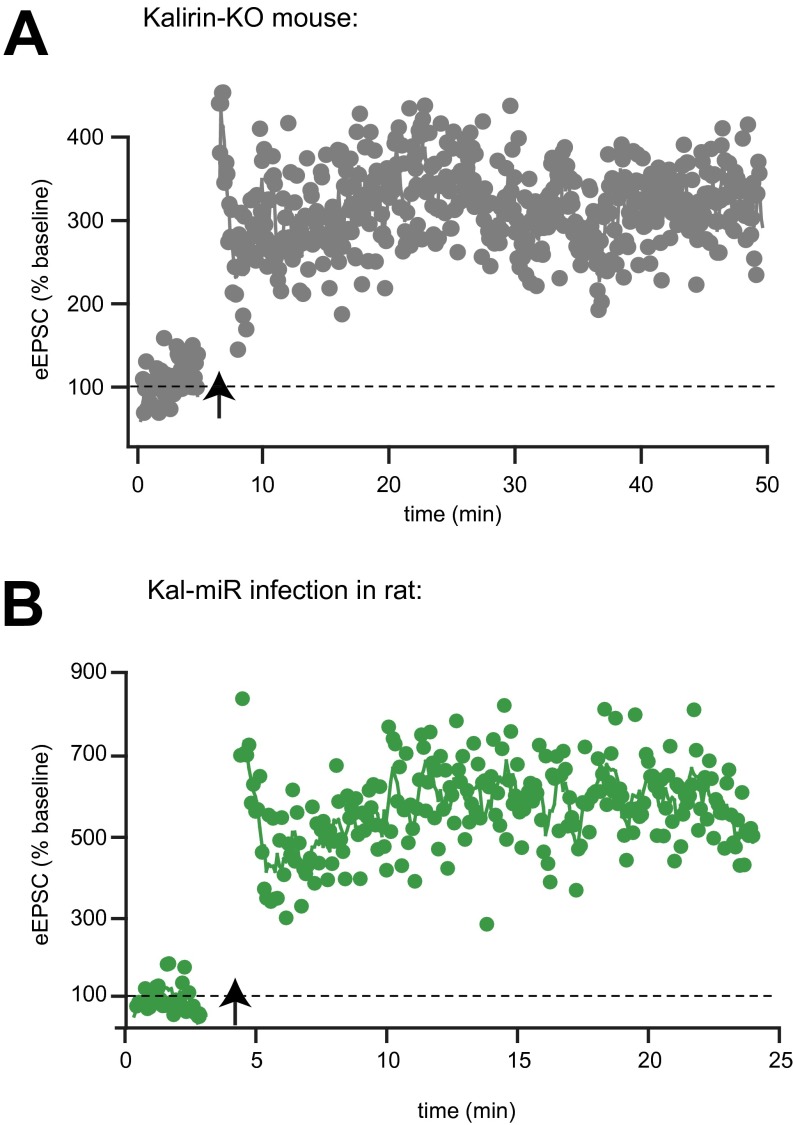

Fig. S5.

LTP is observed in Kalirin KO mice and following acute knockdown of Kalirin expression. (A) LTP induction in a CA1 pyramidal neuron from a Kalirin KO mouse lacking all Kalirin isoforms. (B) LTP induction in a rat CA1 pyramidal neuron following acute knockdown of Kalirin expression using a Kal-miR–containing lentivirus.

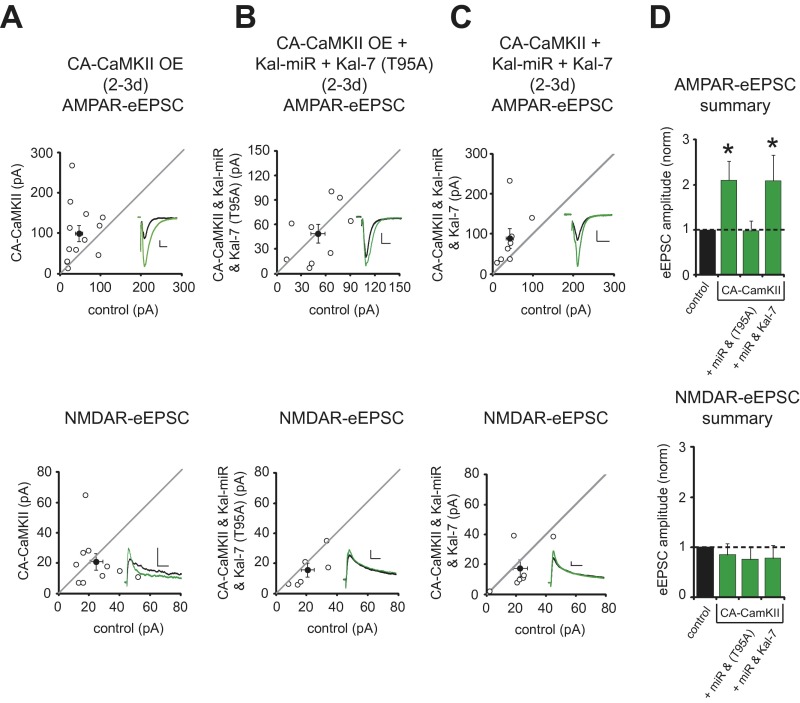

Given that Kalirin and Trio are functionally redundant proteins in their support of synaptic structure and function, it stands to reason that they would serve functionally redundant roles in their support of LTP. Ideally, this would be investigated by examining LTP following simultaneous knockdown of Kalirin and Trio expression; however, this was not feasible, because synaptic transmission, including the NMDAR-eEPSC, was profoundly impaired (Fig. 2C). Our goal was then to develop a strategy whereby the ability of Kalirin and Trio to maintain basal synaptic transmission, including NMDAR-eEPSCs, was left intact, but the ability of CaMKII to act on these proteins was disrupted. We found that Kal-7 restored baseline levels of AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission independent of CaMKII and T95 (Fig. S3 D–F). Furthermore, Kal-7’s ability to increase AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude above baseline levels required CaMKII activation (Fig. S3 A–C). Therefore, we conclude that a CaMKII/T95-independent baseline level of Kal-7 activity supports baseline AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission, and that CaMKII phosphorylation of T95 is specifically required to boost Kal-7 activity and increase synaptic AMPAR expression above baseline levels. We also found that expression of Kal-7 (T95A) prevented Trio-9 OE from increasing AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude without compromising baseline glutamatergic transmission (Fig. 5 A and B). Thus, Kal-7 (T95A) competes with the ability of recombinant Trio to enhance synaptic AMPAR expression. Such competition likely results from the limited number of Kalirin/Trio molecules that are available at a synapse. Therefore, we reasoned that expressing the Kal-miR while at the same time using a strong promoter to drive the expression of recombinant Kal-7 (T95A) should eliminate endogenous Kalirin expression and out-compete the influence of endogenous Trio proteins with a form of Kal-7 that cannot be phosphorylated by CaMKII. This manipulation should thus prevent CaMKII signaling through both proteins without effecting baseline transmission. We first tested the effectiveness of this strategy using a constitutively active form of CaMKII (CA-CaMKII). Short-term OE of CA-CaMKII produced a selective increase in AMPA-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. S6 A and D), which is generally considered a proxy for LTP (17, 18). We found that coexpression of Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), but not of WT Kal-7, eliminated the ability of CA-CaMKII to increase AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. S6 B–D).

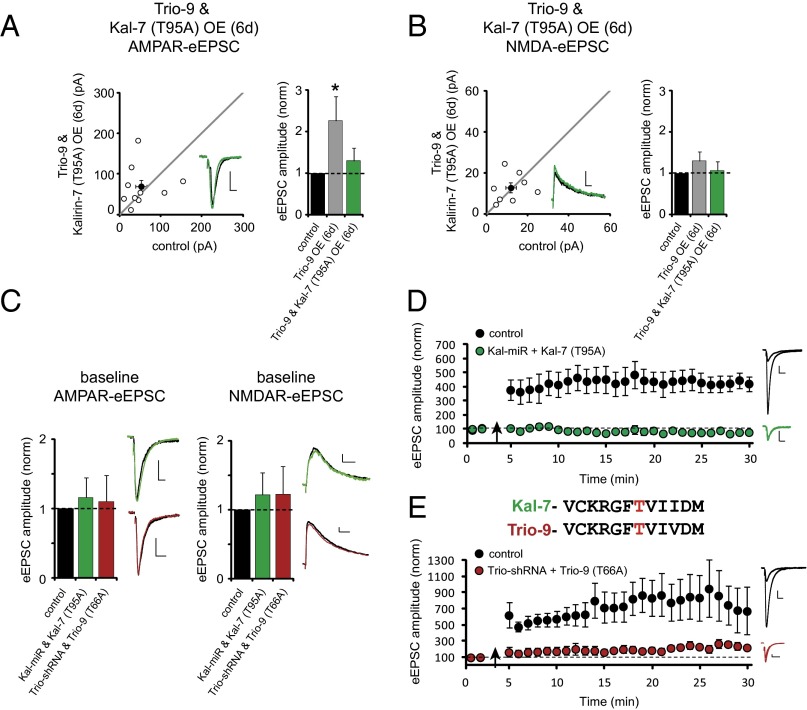

Fig. 5.

CaMKII phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio is required for LTP induction. (A and B) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles represent mean ± SEM. The distributions show that co-OE of Trio-9 and Kal-7 (T95A) for 6 d had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (A; n = 10 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (B; n = 8 pairs). (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.) The bar graphs to the right of the scatterplots are normalized to control comparing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in A and B with that shown in Fig. 1C. (C) Bar graphs plotting average baseline AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Left) and NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Right) of CA1 pyramidal neurons coelectroporated with Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) or Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A) normalized to unelectroporated controls. (Left) Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), n = 9 pairs; Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A), n = 5 pairs. (Right) Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), n = 9 pairs; Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A), n = 5 pairs. (D) Plots of mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude of control unelectroporated CA1 pyramidal neurons (black) and CA1 pyramidal neurons coelectroporated with Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) (green) normalized to the mean AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude before an LTP induction protocol (arrow) [control, n = 6 neurons; Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), n = 7 neurons]. Sample AMPAR-eEPSC current traces from control (black) and electroporated (green) neurons before and after LTP induction are shown to the right of the graph. (Scale bars: 20 ms, 20 pA.) (E) Plots of mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude of unelectroporated CA1 pyramidal neurons (black) and CA1 pyramidal neurons coelectroporated with Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A) (red) normalized to the mean AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude before an LTP induction protocol (arrow) [control, n = 5 neurons; Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A), n = 4 neurons]. Sample AMPAR-eEPSC current traces from a control (black) and an electroporated (red) neuron before and after LTP induction are shown to the right of the graph. (Scale bars: 20 ms, 20 pA.)

Fig. S6.

Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) coexpression blocks CA-CaMKII enhancement of synaptic AMPAR function. (A–C) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. (A) Distributions showing that CA-CaMKII OE for 2–3 d increases AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 12 pairs; *P = 0.01), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 10 pairs). (B) Coexpression of Kal-miR, Kal-7 (T95A), and CA-CaMKII had no effect on AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 9 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 6 pairs). (C) Coexpression of Kal-miR, Kal-7, and CA-CaMKII increased AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude (Upper; n = 8 pairs; *P = 0.02), but not NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Lower; n = 7 pairs). (D) Bar graphs normalized to control summarizing mean ± SEM AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSC data in A–C. (Insets) Sample current traces from control (black) and transfected (green) neurons. (Scale bars: 20 ms for AMPA, 50 ms for NMDA, 20 pA.)

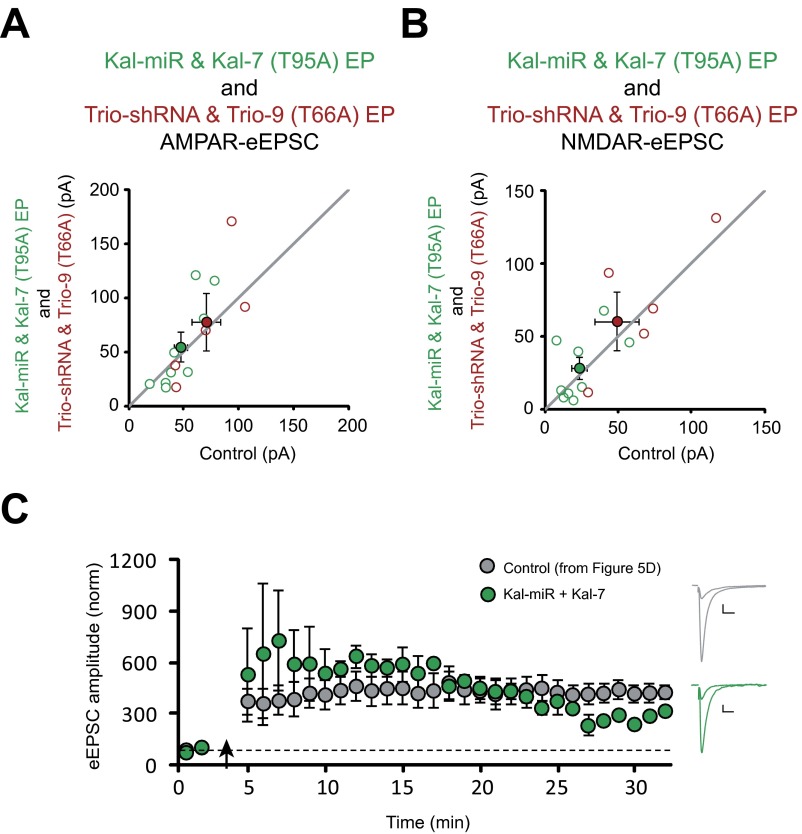

Taken together, our data suggest that coexpression of Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) can be used to maintain the CaMKII-independent synapse-supporting role of Kalirin/Trio and, most importantly, NMDAR-EPSCs while disrupting the ability of CaMKII to signal via these two RhoGEFs. Therefore, if CaMKII phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio are required for LTP induction, then coelectroporation of CA1 pyramidal neurons with Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) should block LTP without compromising baseline transmission. As expected, we found that this manipulation did not affect baseline AMPAR- or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude (Fig. 5C and Fig. S7 A and B). Remarkably, however, coexpression of Kal-miR with Kal-7 (T95A) completely prevented LTP induction (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, coexpression of Kal-miR with Kal-7 supported LTP induction (Fig. S7C). Because the Kal-7 T95 residue is conserved in Trio, we mutated this threonine to an alanine in Trio-9 [Trio-9 (T66A)]. Coexpression of Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A) in CA1 pyramidal neurons also prevented the induction of LTP without affecting baseline glutamatergic transmission (Fig. 5 C and E).

Fig. S7.

Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) coelectroporation and Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A) coelectroporation do not affect baseline transmission, and Kal-miR and Kal-7 coelectroporation supports LTP. (A and B) Scatterplots showing amplitudes of AMPAR- and NMDAR-eEPSCs for single pairs of control and transfected neurons (open circles). Filled circles indicate mean ± SEM. The distributions show that in utero coelectroporation of Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A) and coelectroporation of Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A) do not affect AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude [A: Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), n = 9 pairs; Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A), n = 5 pairs) or NMDAR-eEPSC amplitude [B: Kal-miR and Kal-7 (T95A), n = 9 pairs; Trio-shRNA and Trio-9 (T66A), n = 5 pairs]. (C) Plots of mean ± SEM AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude of CA1 pyramidal neurons coelectroporated with Kal-miR and Kal-7 (green) normalized to the mean AMPAR-eEPSC amplitude before an LTP induction protocol (arrow) (n = 2 neurons). Sample AMPAR-eEPSC current traces from a control (gray, from Fig. 5D) and an electroporated (green) neuron before and after LTP induction are shown to the right of the graph. (Scale bars: 20 ms, 20 pA.)

Considering that inhibiting Kalirin or Trio function alone does not prevent LTP, our data strongly suggest that simultaneously inhibiting the ability of Kalirin and Trio to enhance synaptic AMPAR expression is required to block LTP, and indicate that the role of CaMKII in LTP can be accounted for by an ability to phosphorylate both of these proteins.

Discussion

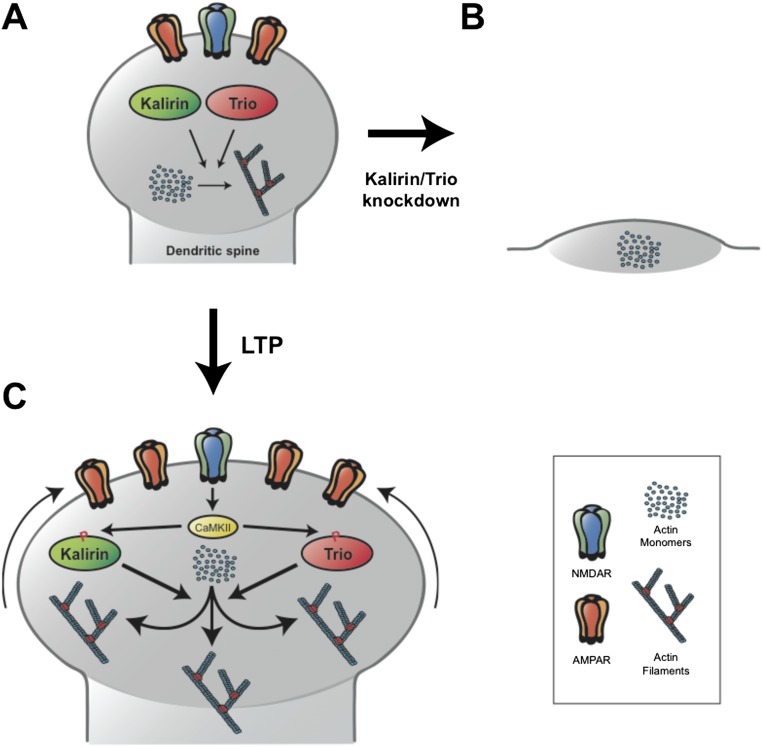

Here we show that the RhoGEFs Kalirin and Trio together play two essential roles at excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. First, our data demonstrate that Kalirin and Trio proteins serve largely redundant and critical roles in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of excitatory synapses in the hippocampus (Fig. S8 A and B). The mechanism underlying this role is still poorly understood, but likely involves the ability of Kalirin and Trio proteins to maintain the actin polymerization critical for the structural stability of dendritic spines. Second, Kalirin and Trio appear to serve largely redundant roles in supporting LTP, with these two RhoGEFs likely representing the immediate downstream targets of CaMKII during LTP induction (Fig. S8 A and C). These two modes of action of Kalirin and Trio appear to be independent, in that disruption of CaMKII signaling through Kal-7 has no effect on synaptic integrity.

Fig. S8.

Model of Kalirin and Trio function in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Baseline excitatory synaptic structure and function are maintained by basal levels of actin polymerization supported of Kalirin and Trio. (B) Simultaneous knockdown of Kalirin and Trio expression prevents sufficient actin polymerization to maintain synaptic structure and function, leading to the collapse of excitatory synapses. (C) During LTP, phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio by CaMKII increases the ability of these RhoGEFs to facilitate actin polymerization, resulting in synapse enlargement and increased synaptic AMPAR expression.

Our data demonstrate that Kalirin and Trio are functionally redundant proteins that together play a fundamental role in the structure and function of excitatory synapses. Previous studies in Kalirin KO mice have found moderately reduced spine density in cortical neurons (19), but either no change (10, 19) or a modest decrease (20) in spine density in hippocampal neurons. Given their similarity, it is reasonable to infer that Kalirin and Trio serve similar roles in supporting synaptic structure. Interestingly, we found that knockdown of Kalirin or Trio expression individually resulted in a largely AMPAR-specific dysfunction, with NMDAR function mostly preserved, indicating that the total number of synapses in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is preserved by eliminating Kalirin or Trio alone. However, knockdown of Kalirin and Trio simultaneously resulted in near-complete elimination of synaptic AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated currents and dendritic spines. Thus, a level of actin polymerization sufficient to support excitatory synapses cannot be maintained in the absence of both Kalirin and Trio. We assert that the variability in spine phenotypes observed following knockout and knockdown of Kalirin expression arises from the degree to which Trio proteins are able to compensate for the loss of Kalirin.

Previous studies have suggested that the RhoGEF Kalirin may play a role in sLTP and LTP (9, 21); however, knockdown or knockout of the expression of all Kalirin isoforms in mice does not prevent LTP induction (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5) (10). Therefore, although Kalirin might still be involved in LTP, it is not solely responsible for its induction. One possible explanation for this is that Kalirin and Trio represent redundant proteins supporting LTP.

To selectively inhibit CaMKII signaling through both Kalirin and Trio, we coexpressed Kal-miR and Kal-miR–resistant Kal-7 (T95A). We performed this manipulation to eliminate endogenous Kalirin expression and out-compete the influence of endogenous Trio proteins with a form of Kal-7 that cannot be phosphorylated by CaMKII. Remarkably, this manipulation completely eliminated LTP induction without affecting baseline glutamatergic neurotransmission. Although we believe Kal-7 (T95A)-mediated inhibition of Trio function arises from a dilution of endogenous Trio proteins, we cannot exclude the possibility that Kal-7 (T95A) acts as a dominant negative against Trio function. For example, it may be possible that Kal-7 (T95A) gains preferential access to Kalirin/Trio binding sites at synapses. We also discovered that mutating the same threonine to an alanine in Trio-9 blocked LTP when expressed in CA1 pyramidal neurons. The foregoing findings demonstrate that the importance of this threonine residue is conserved between Kalirin and Trio. Furthermore, Kal-7–mediated enhancement of synaptic AMPAR expression requires Cdc42, a Rho GTPase recently found to be critical in LTP and sLTP (7, 8). Although Kalirin and Trio are not thought to activate Cdc42 directly, they might activate Cdc42 indirectly through their ability to activate RhoG (22). We have also shown that mimicking CaMKII phosphorylation of Kal-7 T95 is sufficient to selectively and robustly enhance synaptic AMPAR expression in the absence of synaptic activity. This finding suggests that the phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio is instructive in LTP induction rather than permissive. Although one published study did not identify Kal-7 T95 phosphorylation following an in vitro CaMKII phosphorylation assay (23), another earlier study did identify T95 as a CaMKII phosphorylation site (9). Our data strongly agree with the earlier study, given our finding that T95 is required for Kal-7– and CA-CaMKII–mediated enhancement of synaptic AMPAR transmission. We also found that phosphonull and phosphomimetic mutations of T95 bidirectionally control Kal-7 function in neurons. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that CaMKII gives rise to functional LTP through the phosphorylation of Kalirin and Trio, which in turn facilitates actin polymerization and synapse enlargement via activation of Rho GTPases, like Cdc42 (Fig. S8C).

Previous studies have argued that LTP arises from direct phosphorylation of AMPAR subunits by CaMKII (24–26). Conversely, recent work from our laboratory demonstrates that LTP can still be induced when AMPARs are replaced with kainate receptors that share little sequence homology with AMPARs (27). This finding strongly suggests that AMPARs are not required for LTP induction and is more in line with the synaptic structure-based RhoGEF-mediated mechanism of LTP induction presented in the present study. Given the importance of Kalirin and Trio in CaMKII-dependent LTP, it will be interesting to determine whether these proteins are involved in other forms of synaptic plasticity as well.

Materials and Methods

Electrophysiology.

All experiments were performed in accordance with established protocols approved by the University of California, San Francisco’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Whole-cell recordings were performed as described previously (28). Slice cultures were prepared from P6–P9 rat or mouse pups as described previously (29) and recorded on day in vitro (DIV) 7–8. Acute slices for LTP experiments were prepared from P17–P23 mice. All slices were maintained during recording in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 26.2 mM NaHCO3 and 11 mM glucose. For acute slices, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 1.3 mM MgSO4 were added to the aCSF, and 4 mM CaCl2 and 4 MgSO4 were added for organotypic slice cultures. The internal whole-cell recording solution contained 135 mM CsMeSO4, 8 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 0.3 mM EGTA, 5 mM QX-314, 4 mM Mg-ATP, and 0.3 mM Na-GTP. Osmolarity was adjusted to 290–295 mOsm, and pH-buffered at 7.3–7.4. Synaptic responses were evoked by stimulating with a monopolar glass electrode filled with aCSF in the stratum radiatum of CA1. Biolistic transfections and E15.5 electroporations were carried out as described previously (30, 31).

Spine Imaging.

Control and experimental CA1 pyramidal neurons in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures were biolistically transfected with FUGW-GFP or FHUGW-GFP/mCherry constructs at ∼18–20 h after plating. At 7–8 d after transfection, confocal imaging was performed on CA1 pyramidal neurons brightly labeled with GFP in live tissue in Hepes-buffered aCSF containing 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CaCl2 using a Nikon Spectral C1si confocal microscope with a NIR Apo 60× W objective. Z-stacks were made of 30-µm sections of secondary apical dendrites using EZ-C1 software (Nikon). Imaging was performed on two or three dendrites per neuron, and the spine density was averaged. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test.

SI Materials and Methods

Experimental Constructs.

The Kalirin-miR construct was made using a previously characterized RNAi target sequence, GCAGTACAATCTGGCCATGT (9). This target sequence was subcloned into pCDNA6.2/EmGFP using the BLOCK-iT miRNA kit (Invitrogen), resulting in GFP followed by the miRNA. The resulting GFP-miRNA construct was then subcloned into pFUGW for biolistic and lentiviral expression. The following target sequences were used for shRNA: TTCAGACGCAGCACAATCA for Trio (a generous gift from Betty A. Eipper, University of Connecticut) and TACAAACACAACATAATCA for Cdc42, characterized previously (7). For biolistic and lentiviral expression, Trio and Cdc42shRNAs were subcloned behind the H1 promoter region of a GFP- or mCherry- expressing pFHUGW expression vector. The cDNA used for Kalirin-7 OE constructs was taken from a construct containing mouse Kalirin-7 cDNA (Open Biosystems; accession no. BC157950). RNAi proof Kalirin-7 was generated based on a previously characterized design (9). Human Trio-9 (or Trio-9s in ref. 12) was generated from a Trio-FL cDNA generously provided by Betty A. Eipper. “RNAi-proof” Trio-9 was generated by five silent point mutations within the RNAi target sequence (TACAAACACAACATAATCA). The cDNA used for the Tiam1 OE construct was taken from a construct containing human Tiam1 cDNA (Open Biosystems; accession no. BC117196). CA-CaMKII was generated based on the (T286D/T305A/T306A) strategy described previously (17).

Point mutations and RNAi-proofing of all cDNAs were done using overlap-extension PCR followed by In-Fusion cloning (Clontech). For biolistic expression, all Kalirin, Trio, and Tiam1 cDNAs were cloned into a pCAGGs vector containing IRES mCherry, and the CA-CaMKII cDNA was cloned into a pFHUGW vector containing IRES GFP. A pFUGW vector expressing only GFP was coexpressed with pCAGG-IRES-mCherry constructs to enhance the identification of transfected neurons, and served as a control vector for spine imaging.

Neuronal Transfection.

Sparse biolistic transfections of organotypic slice cultures were performed as described previously (28–30). In brief, 80 µg of mixed plasmid DNA was coated onto 1-µm-diameter gold particles in 0.5 mM spermidine, precipitated with 0.1 mM CaCl2, and washed four times in pure ethanol. The gold particles were coated onto PVC tubing, dried using ultrapure N2 gas, and stored at 4 °C in desiccant. DNA-coated gold particles were delivered with a Helios Gene Gun (Bio-Rad). Construct expression was confirmed by GFP and/or mCherry epifluorescence.

For in utero electroporation, ∼E15.5 pregnant mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in O2 and then injected with buprenorphine for analgesia. Embryos within the uterus were temporarily removed from the abdomen and injected with 2 µL of mixed plasmid DNA into the left ventricle via a beveled micropipette. pFUGW-RNAi, pCAGGs-Kalirin, and pCAGGs-Trio constructs at 1.5–3 µg µL−1 were used. Each embryo was electroporated with five 50-ms, 35-V pulses. The positive electrode was placed in the lower right hemisphere, and the native electrode was placed in the upper left hemisphere (31). After electroporation, the embryos were sutured into the abdomen and then killed on P17–P23 for recording.

Electrophysiology.

Voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from CA1 pyramidal neurons in either acute hippocampal slices or organotypic slice cultures from rats and mice. For acute slices, 300-µm transverse slices were cut using a Microslicer DTK-Zero1 (Ted Pella) in chilled high-sucrose cutting solution containing 2.5 mM KCl, 7 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 7 mM glucose, 210 mM sucrose, 1.3 mM ascorbic acid, and 3 mM sodium pyruvate. The slices were then incubated for 30 min at 34 °C in aCSF containing 119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, and 11 mM glucose. For acute slices, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 1.3 mM MgSO4 were added to the aCSF, and for organotypic slice cultures, 4 mM CaCl2 and 4 mM MgSO4 were added. The aCSF was bubbled with 95% (vol/vol) O2 and 5% (vol/vol) CO2 to maintain pH, and the acute slices were allowed to recover at room temperature for 45 min to 1 h.

Cultured slices were prepared as described previously (29), and recordings were made from slices at DIV 7 or 8. When specified, slice cultures were cultured in medium containing 200 µM AP5 and 20 µM NBQX to block glutamatergic transmission. AP5 and NBQX were removed 2 h before recording. During recording, slices were transferred to a perfusion stage on an Olympus BX50WI upright microscope and perfused at 2.5 mL min−1 with aCSF containing 0.1 mM picrotoxin; 2–5 mM 2-chloroadenosine was included in the aCSF when recording from organotypic slice cultures.

Synaptic responses were evoked by stimulation with a monopolar glass electrode filled with aCSF in the stratum radiatum of CA1. To ensure stable recording, membrane holding current, input resistance, and pipette series resistance were monitored throughout recording. Data were gathered through a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments), filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz. Where specified, acute and cultured hippocampal slices were obtained from Kalirin KO mice (10) (generously provided by Peter Penzes, Northwestern University, Chicago).

Whole-Cell Synaptic Recordings and LTP.

Simultaneous dual whole-cell recordings were made between GFP- and/or mCherry-positive experimental cells as identified by epifluorescence and neighboring nontransfected control cells. The internal recording solution contained 135 mM CsMeSO4, 8 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 0.3 mM EGTA, 5 mM QX-314, 4 mM Mg-ATP, and 0.3 mM Na-GTP. Osmolarity was adjusted to 290–295 mOsm, and pH-buffered at 7.3–7.4. AMPAR-mediated responses were isolated by voltage-clamping the cell at −70 mV, whereas NMDA-mediated responses were recorded at +40 mV, with amplitudes measured at 150 ms after stimulation to avoid contamination by the AMPAR current. To minimize runup of baseline responses during LTP, cells were held cell-attached for ∼1–2 min before breaking into the cell. LTP was induced by holding neurons at 0 mV during a 2-Hz stimulation of Schaffer collaterals for 90 s.

Spine Imaging.

For spine density analysis, control and experimental CA1 pyramidal neurons in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures made from P6 rat pups were biolistically transfected with FUGW-GFP or FHUGW-GFP/mCherry constructs at ∼18–20 h after plating. At 7 d after transfection, confocal imaging was performed on CA1 pyramidal neurons brightly labeled with GFP in live tissue in Hepes-buffered aCSF containing 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CaCl2 using a Nikon Spectral C1si confocal microscope with an NIR Apo 60× W objective. Z-stacks were made of 30-µm sections of secondary apical dendrites located ∼30 µm from the soma using EZ-C1 software (Nikon). Imaging was performed on two or three dendrites per neuron, and the spine density values were averaged. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test.

For spine morphology measurements, images were acquired at DIV 7 using super-resolution microscopy (N-SIM Microscope System; Nikon). For use with the available inverted microscope and oil-immersion objective lens, slices were fixed in 4% PFA/4% sucrose in PBS and washed three times with PBS. To amplify the GFP signal, slices were then blocked and permeabilized in 3% BSA in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X and then stained with primary antibody against GFP (A-11122, 2 μg/mL; Life Technologies), followed by washes in PBS and Triton-X and then staining with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (A-11034, 4 μg/mL; Life Technologies). Slices were further processed with an abbreviated SeeDB-based protocol (32) in an attempt to reduce spherical aberration. Slices were then mounted in SlowFade Gold (Life Technologies) for imaging. Z-stacks were made of 30-µm sections of secondary apical dendrites located ∼30 µm from the soma. Images were acquired with a 100× oil objective in 3D-SIM mode using the supplied SIM grating (3D EX V-R 100×/1.49), and then processed and reconstructed using the supplied software (NIS-Elements; Nikon). Morphological analysis was done on individual sections using ImageJ to perform geometric measurements on spines extending laterally from the dendrite. Head diameter was measured perpendicular to the spine neck axis through the thickest part of the spine head. Head diameter was obtained using full width at tenth maximum measurements based on Gaussian fits to approximate manual head measurement.

Lentiviral Production.

Lentiviral particles for the viral expression of Kalirin-miR and Trio-shRNA were produced in HEK293T cells cotransfected with the miRNA or shRNA constructs in FUGW along with psPAX2 and pVSV-G using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche). Viral particle-containing supernatant was collected and filtered, after which the viral particles were precipitated using PEG-it solution (System Biosciences) and then collected via centrifugation. Viral particles were resuspended in Opti-Mem and stored at −80 °C until use.

Lentivirus Injection.

Rat viral injections were performed at P30. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and immobilized on a stereotaxic frame using ear and palate bars designed for rats (David Kopf Instruments). Then 250 nL per hemisphere was injected at a rate of 500 nL/min via a Hamilton 88011 syringe driven by a Micro4 microsyringe pump (World Precision Instruments). All experiments were performed in accordance with established protocols approved by the University of California, San Francisco’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Acute hippocampal slices were prepared for recording 10 d later.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

To assess the efficiency of knockdown, dissociated hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared from E18–E19 rats. Hippocampi were surgically isolated, then dissociated by 0.25% trypsin, followed by gentle mechanical trituration. Cells were plated on poly-d-lysine–treated glass coverslips and maintained in a neurobasal (Invitrogen)-based medium supplemented with B27, penicillin-streptomycin, and l-glutamine at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Lentiviruses containing the miRNA and shRNA constructs were introduced 1 d after plating. Ten days later, RNA was harvested by lysis and reverse-transcribed to synthesize cDNA using a Cells-to-CT Kit (Thermo Fisher). Amplification of cDNA by real-time PCR was quantified using SYBR Green in a Stratagene Mx3005P PCR system with the following sequence-specific primers: Kalirin-7, forward, AAACACCAGCCAAACTGAGG, reverse, GGTTGCCATCCTTGTCACTC; Trio, forward, CCTAGACTGTGTGGTACGATG, reverse, AGATGTTCTCAGGCTTTAGG.

Western Blot Analysis.

HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. The cells were plated onto six-well plates and grown until 50% confluence, followed by transfection with the Trio-9 expression construct together with either Trio-shRNA or GFP using FuGENE HD transfection reagent. An RNAi/Trio-9 DNA ratio of 30:1 was used. Then, 48 h later, cell lysates were prepared and run on a NuPage Novex 4–12% precast gel (Life Technologies) with 15 μg of protein loaded per lane. Membranes were probed with antibodies specific for Trio (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β-actin (1:1,000; Millipore). IRDye 680/800-coupled secondary antibodies were then used for detection. Membranes were scanned using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for all experiments involving unpaired data and the two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test for all experiments using paired whole-cell data, including all synaptic replacement and synaptic OE data. LTP data were gathered from interleaved and pairs of control and experimental neurons; thus, comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U test. Data analysis was carried out in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics), KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software), and Excel (Microsoft).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the R.A.N. laboratory for helpful feedback and comments during the study. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health to R.A.N. and grants from the Brain and Behavior Research Fund and National Institutes of Mental Health to B.E.H. All primary data are archived in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology, University of California, San Francisco.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600179113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Huganir RL, Nicoll RA. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: The last 25 years. Neuron. 2013;80(3):704–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicoll RA, Roche KW. Long-term potentiation: Peeling the onion. Neuropharmacology. 2013;74:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lüscher C, Malenka RC. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD) Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(6):a005710. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. Expression of NMDA receptor-dependent LTP in the hippocampus: Bridging the divide. Mol Brain. 2013;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lisman J, Yasuda R, Raghavachari S. Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(3):169–182. doi: 10.1038/nrn3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiens KM, Lin H, Liao D. Rac1 induces the clustering of AMPA receptors during spinogenesis. J Neurosci. 2005;25(46):10627–10636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1947-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murakoshi H, Wang H, Yasuda R. Local, persistent activation of Rho GTPases during plasticity of single dendritic spines. Nature. 2011;472(7341):100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim IH, Wang H, Soderling SH, Yasuda R. Loss of Cdc42 leads to defects in synaptic plasticity and remote memory recall. eLife. 2014;3:02839. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Z, et al. Kalirin-7 controls activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines. Neuron. 2007;56(4):640–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Z, et al. Hippocampal phenotypes in kalirin-deficient mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma XM, Huang JP, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Expression of Trio, a member of the Dbl family of Rho GEFs, in the developing rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2005;482(4):333–348. doi: 10.1002/cne.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPherson CE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Multiple novel isoforms of Trio are expressed in the developing rat brain. Gene. 2005;347(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portales-Casamar E, Briancon-Marjollet A, Fromont S, Triboulet R, Debant A. Identification of novel neuronal isoforms of the Rho-GEF Trio. Biol Cell. 2006;98(3):183–193. doi: 10.1042/BC20050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manabe T, Wyllie DJ, Perkel DJ, Nicoll RA. Modulation of synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation: effects on paired pulse facilitation and EPSC variance in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70(4):1451–1459. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolias KF, et al. The Rac1-GEF Tiam1 couples the NMDA receptor to the activity-dependent development of dendritic arbors and spines. Neuron. 2005;45(4):525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming IN, Elliott CM, Buchanan FG, Downes CP, Exton JH. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates Tiam1 by reversible protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12753–12758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pi HJ, Otmakhov N, Lemelin D, De Koninck P, Lisman J. Autonomous CaMKII can promote either long-term potentiation or long-term depression, depending on the state of T305/T306 phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2010;30(26):8704–8709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0133-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(3):175–190. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahill ME, et al. Kalirin regulates cortical spine morphogenesis and disease-related behavioral phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(31):13058–13063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma XM, et al. Kalirin-7 is required for synaptic structure and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28(47):12368–12382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemtiri-Chlieh F, et al. Kalirin-7 is necessary for normal NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blangy A, et al. TrioGEF1 controls Rac- and Cdc42-dependent cell structures through the direct activation of rhoG. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 4):729–739. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiraly DD, et al. Identification of kalirin-7 as a potential post-synaptic density signaling hub. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(6):2828–2841. doi: 10.1021/pr200088w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi S, Hayashi Y, Esteban JA, Malinow R. Subunit-specific rules governing AMPA receptor trafficking to synapses in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Cell. 2001;105(3):331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm J, et al. Synaptic incorporation of AMPA receptors during LTP is controlled by a PKC phosphorylation site on GluR1. Neuron. 2006;51(2):213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HK, et al. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit is required for synaptic plasticity and retention of spatial memory. Cell. 2003;112(5):631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granger AJ, Shi Y, Lu W, Cerpas M, Nicoll RA. LTP requires a reserve pool of glutamate receptors independent of subunit type. Nature. 2013;493(7433):495–500. doi: 10.1038/nature11775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu W, et al. Subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors revealed by a single-cell genetic approach. Neuron. 2009;62(2):254–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnell E, et al. Direct interactions between PSD-95 and stargazin control synaptic AMPA receptor number. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13902–13907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elias GM, Elias LA, Apostolides PF, Kriegstein AR, Nicoll RA. Differential trafficking of AMPA and NMDA receptors by SAP102 and PSD-95 underlies synapse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(52):20953–20958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811025106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ke MT, Fujimoto S, Imai T. SeeDB: A simple and morphology-preserving optical clearing agent for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):1154–1161. doi: 10.1038/nn.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goold CP, Nicoll RA. Single-cell optogenetic excitation drives homeostatic synaptic depression. Neuron. 2010;68(3):512–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]