Significance

The mechanism of action of the artemisinin (ART) class of antimalarial drugs, the most important antimalarial drug class in use today, remains controversial, despite more than three decades of intensive research. We have developed an unbiased chemical proteomic approach using a suite of ART activity-based protein profiling probes to identify proteins within the malaria parasite that are alkylated by ART, including proteins involved in glycolysis, hemoglobin metabolism, and redox defense. The data point to a pleiotropic mechanism of drug action for this class and offer a strategy for investigating resistance mechanisms to ART-based drugs as well as mechanisms of action of other endoperoxide-based drugs.

Keywords: artemisinin, antimalarial, bioactivation, chemical proteomics, molecular targets

Abstract

The artemisinin (ART)-based antimalarials have contributed significantly to reducing global malaria deaths over the past decade, but we still do not know how they kill parasites. To gain greater insight into the potential mechanisms of ART drug action, we developed a suite of ART activity-based protein profiling probes to identify parasite protein drug targets in situ. Probes were designed to retain biological activity and alkylate the molecular target(s) of Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 parasites in situ. Proteins tagged with the ART probe can then be isolated using click chemistry before identification by liquid chromatography–MS/MS. Using these probes, we define an ART proteome that shows alkylated targets in the glycolytic, hemoglobin degradation, antioxidant defense, and protein synthesis pathways, processes essential for parasite survival. This work reveals the pleiotropic nature of the biological functions targeted by this important class of antimalarial drugs.

Malaria is a global health problem with 214 million new cases of malaria and 438,000 deaths reported in 2015, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa (1). The endoperoxide class of antimalarial drugs, such as artemisinin (ART), is the first line of defense against malaria infection against a backdrop of multidrug-resistant parasites (2) and lack of effective vaccines (3, 4). Given the effectiveness of the ART class, the question arises: how do these drugs kill parasites? A suggested mechanism of action involves the cleavage of the endoperoxide bridge by a source of Fe2+ or heme. This cleavage results in the formation of oxyradicals that rearrange into primary or secondary carbon-centered radicals. These radicals have been proposed to alkylate parasite proteins that somehow result in the death of the parasite (5). However, this proposal remains a subject of intense debate (6, 7), while these alkylated proteins are yet to be formally identified. So far, the proposed targets of ART action include a PfATP6 enzyme, the Plasmodium falciparum ortholog of mammalian sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca21-ATPases (SERCAs) (5), translational controlled tumor protein, and heme (5). Additionally, Haynes et al. (8) proposed that ART may act by impairing parasite redox homeostasis as a consequence of an interaction between the drug and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH) and/or other parasite flavoenzymes in the parasite, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). New approaches are required for definitive identification of ART molecular targets. This insight into the drug activation-dependent mechanism of action will be invaluable in the target-led development of more potent drugs with the potential to circumvent the emergence of resistance to current first-line ART-based therapies. The goal of this study was to identify ART-targeted proteins and their interacting partners in P. falciparum. We recently adopted a proteomic approach developed by Speers and Cravatt (9) to synthesize a suite of pyrethroid activity-based protein profiling probes (ABPPs) (10). Using alkyne/azide-coupling partners through “click chemistry,” we identified several cytochrome P450 enzymes that metabolized deltamethrin in rat liver microsomes (10). More recently, a chemical proteomic approach was developed to identify parasite proteins targeted by an albitiazolium antimalarial drug candidate in situ using a photoactivation cross-linking approach (11). However, this generic approach can introduce significant promiscuity in the proteins tagged based on the intracompartmental distribution of drug independent of actual mechanisms.

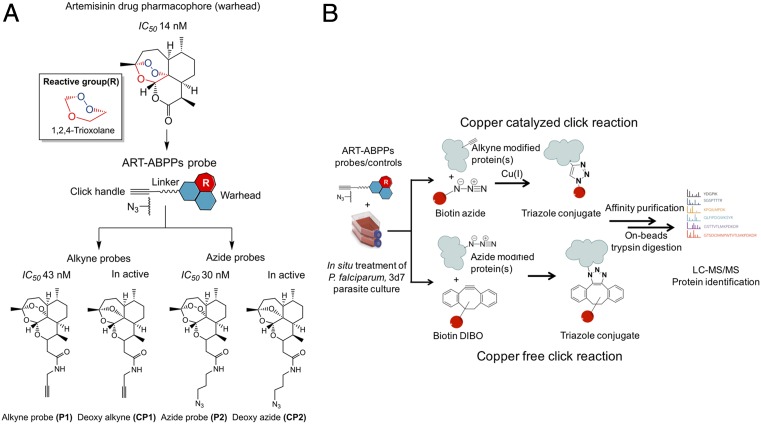

Here, we introduced the design and synthesis of click chemistry-compatible activity-based probes incorporating the endoperoxide scaffold of ART as a warhead to alkylate and identified the ART molecular target(s) in asexual stages of the malaria parasite (Fig. 1). A major advantage of this strategy is that the reporter tags are introduced under “click” reaction conditions performed after the drug has achieved its biological effects, enabling purification, identification, and quantification of alkylated parasite’s proteins and their interacting partners as shown in Fig. 1B. To avoid nonspecific probe-dependent tagging, a common limitation of these approaches, we generated the respective “control” nonperoxide partners to improve the specificity and biological relevance of our resultant tagged protein list.

Fig. 1.

Rational design of the ART-ABPPs. (A) Conversion of ART to ART-ABPPs involves the addition of a clickable handle (i.e., an alkyne or azide to the ART drug pharmacophore by the peptide-coupling method illustrated in SI Text). The structures of the alkyne (P1) and azide (P2) probes and respective inactive deoxy controls CP1 and CP2 with in vitro IC50 values are presented. (B) General workflow of copper-catalyzed and copper-free click chemistry approaches used in the identification of alkylated proteins after in situ treatment of P. falciparum parasite with alkyne and azide ART-ABPPs. The azide- and alkyne-modified proteins are tagged with biotin azide and biotin dibenzocyclooctyne (Biotin-DIBO), respectively, via click reactions followed by affinity purification tandem with LC-MS/MS for protein identification.

Results and Discussion

Rationale of ART Activity-Based Protein Profiling Probes Design and Synthesis.

We synthesized the click probes using techniques optimized and developed in house with the alkyne/azide introduced by an optimized peptide coupling protocol (more details are in SI Text). We varied click handles to expand the utility of ART-ABPPs and compare the efficiency of two distinctive tagging chemistries (i.e., copper-catalyzed and bioorthogonal copper-free click chemistry). Previous work by Meshnick and coworkers (12) showed that six uncharacterized malaria proteins bands were labeled with semisynthetic derivatives of ART (e.g., [3H]-dihydroartemisinin) at pharmacologically relevant concentrations of the drug. Importantly, labeling was not shown using uninfected erythrocytes or when infected cells were treated with the inactive analog, deoxyether (12). Our strategy allows definitive identification of tagged proteins by comparison of active probe alkylation products with those of their nonperoxidic equivalent controls (synthesized as detailed in SI Text). Earlier work suggests that long peptide linkers can introduce cytotoxicity (13). To avoid this issue, peptide linkers of maximum three carbons were used for our alkyne and azide probes.

Antimalarial Activity of ART-ABPPs.

The antimalarial activity of the probes and controls was determined in vitro against P. falciparum 3D7 parasites (SI Text). The azide/alkyne function did not significantly affect antimalarial activity against 3D7 (Fig. 1A). The IC50 values for probe 1 (P1) and probe 2 (P2) were 43.86 (SD = 0.441 nM; n = 3) and 30.26 nM (SD = 0.314 nM; n = 3), respectively, compared with the IC50 of ART of 14 nM (SD = 0.41 nM; n = 3). Importantly, control probes CP1 and CP2 were inactive in agreement with expectations (12, 14). This result supports the essentiality of the endoperoxide bridge and validates our probe plus control pair strategy.

Parasite Protein Labeling and Identification.

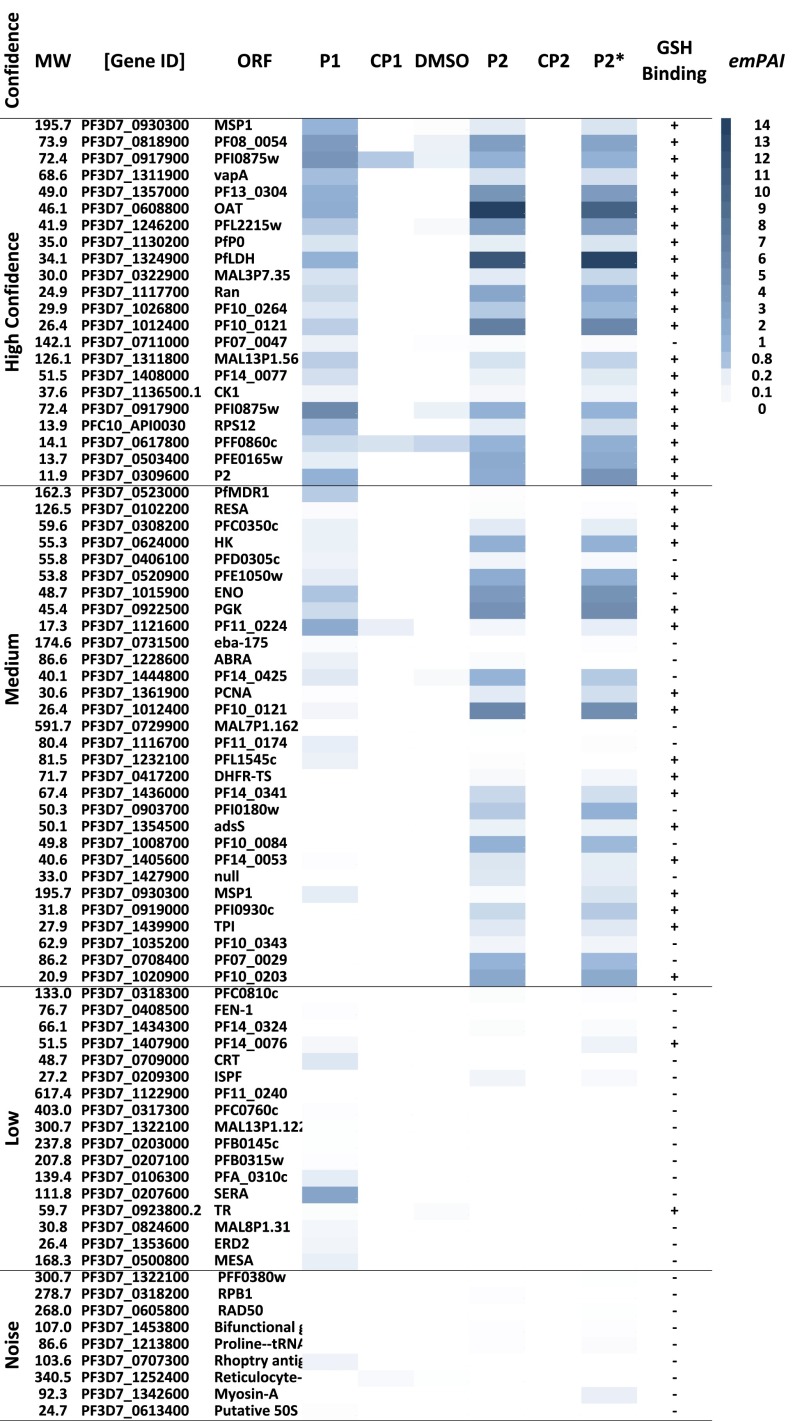

As a next step, we moved to the direct identification of ART molecular target(s) in situ as explained in Methods and Fig. 1B. The Mascot search algorithm was used to identify proteins from the resultant peptides identified by liquid chromatography (LC)–MS/MS, and the exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) was used to provide semiquantitation of protein abundance (15). Heat map analysis (Fig. 2) shows the essentiality of the endoperoxide in protein alkylation. In general, many essential proteins were identified as ART targets with P1 and P2 (Figs. 2 and 3). These results are further supported by 1D gel fluorescence analysis (Fig. S1) for proteomes treated with a trifunctional azido-biotin-rhodamine tag (instead of the biotin azide tag) and subjected to protein purification followed by in-gel fluorescence visualization. With this probe, significant protein labeling was apparent with the active probe P1, whereas no labeling was evident with its alkyne deoxy-ether negative control analog. This result again reinforces the importance of the endoperoxide function for bioactivation (Fig. S1). Using on-bead trypsin digestion of captured proteins with the biotin azide reporter followed by LC-MS/MS identification confidently reported 58 proteins using P1; however, four proteins were detected at very low abundance in two of five replicates in the positive control treatment (CP1) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2A). Multiple t test analysis confirmed that the levels of these proteins tagged by the active probe were significantly higher than in the control experiments (Fig. S2A). This result shows the importance of having a positive control to avoid identification of proteins that bind nonspecifically to the streptavidin column. When DMSO solvent was used as a negative control, nine proteins at very low, insignificant levels were detected in two of five replicates (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2B). These observations emphasize the need to control for nonspecific binding in these complex proteomic experiments.

Fig. 2.

Heat map of the entire proteomic dataset identified by the alkyne and azide ART-ABPPs. Heat map analysis was carried out by plotting the average exponentially modified protein abundance index values for each protein. The data were acquired from multiple independent experiments for each probe [P1, n = 5; CP1, n = 5; DMSO, n = 5; P2, n = 2; CP2, n = 2; P2* (cellular homogenate)]. Each independent replicate was injected into the LC-MS/MS four times to improve the accuracy of protein identification. The heat map plot was clustered into four categories from high confidence to noise according to the hit frequency in all replicates. Protein hits found in seven to nine independent replicates were denoted as being of high confidence, hits seen in four to six replicates were denoted as medium confidence, three hits were denoted as low confidence, and hits seen in only one or two replicates were considered as noise. Proteins were manually searched for the presence (+) and absence (−) of a glutathione (GSH) binding motif according to data published by Kehr et al. (23). Complete datasets of ART proteomes are illustrated in Dataset S1. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide treatment; MW, protein molecular weight in kilodalton; ORF, open reading frame names.

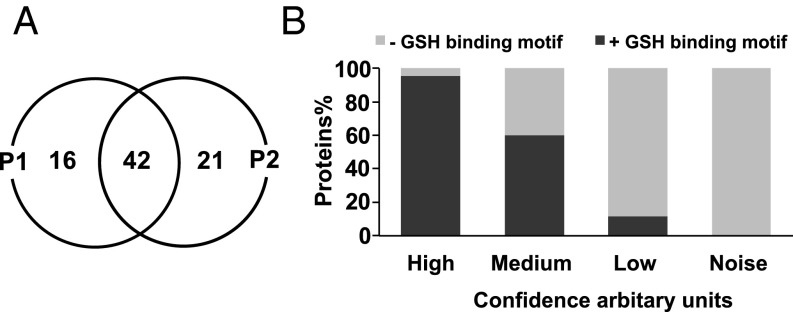

Fig. 3.

Overview of ART-ABPP–tagged proteins. (A) Venn diagram showing overlap between proteins identified with the alkyne (P1) and azide (P2) ART probes. (B) Trend analysis between the confidence in protein identification as described in Fig. 2 and the proportion of those proteins carrying a glutathione (GSH) binding motif (χ2 = 230.1 with a P value < 0.0001).

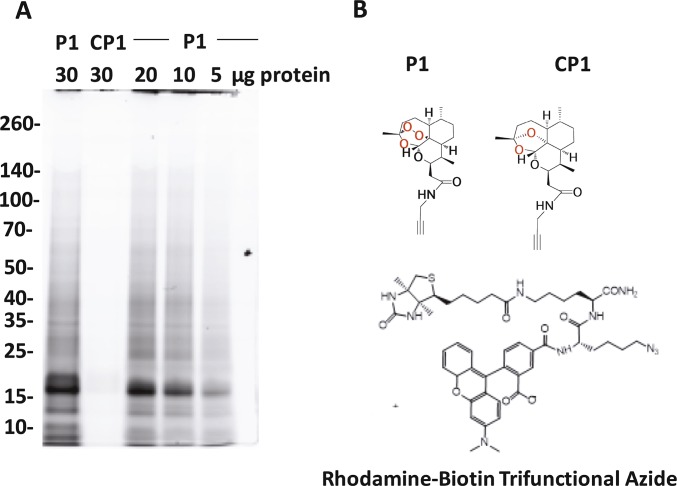

Fig. S1.

Proteins identified in a P. falciparum proteome using alkyne ART-ABPP (P1) vs. its deoxyether analog (control probe; CP1), illustrating the essentiality of the endoperoxide drug pharmacophore for successful protein labeling. (A) Identification SDS/PAGE gel showing alkylated proteins tagged with rhodamine-biotin trifunctional azide by click chemistry. Fluorescent protein bands are clearly visible with active probe P1 at 30, 20, 10, and 5 μg protein loading, with no labeling seen with the inactive control CP1 at 30 μg loading. (B) Chemical structure of the alkyne ART-ABPPs and their respective control.

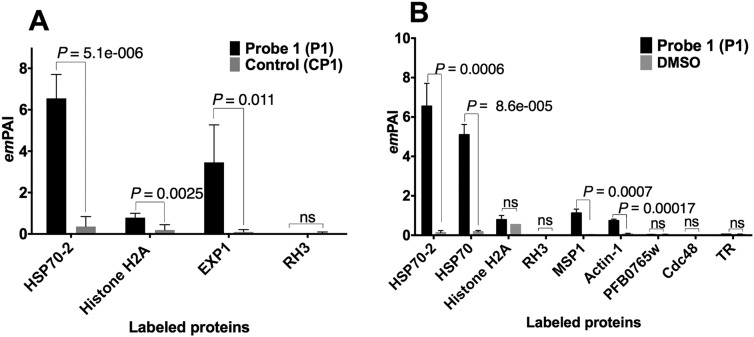

Fig. S2.

Comparison between proteins identified with alkyne ART-ABPP (P1) vs. controls using LC-MS/MS. Multiple t test analysis was used to assess the significance of the labeling event seen with active probe treatment vs. controls (control probe and DMSO solvent). P values were corrected using the Holm–Sidak method. Data are the average of three independent replicates, and labeling with P1 probe was considered significant at P < 0.05. (A) Comparison of proteins identified from the parasite proteome extracted after treatment of the parasite culture in situ with 1 µM P1 vs. 1 µM deoxyartmesinin control probe (CP1). (B) Comparison of proteins identified from the parasite proteome treated with 1 µM P1 vs. DMSO solvent. emPAI, exponentially modified protein abundance index; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; MSP1, merozoite surface protein 1; ns, nonsignificant; RH3, reticulocyte-binding protein 3; TR, thioredoxin reductase.

Studies performed with copper (I) salts and copper complexes have shown the potential for ART activation and rearrangement, similar to that generated by iron (16) under these conditions. ART activation based on copper was considered an unlikely problem during the click reactions used in this study because of the multiple washing steps involved and the use of a reducing environment [DTT and Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine] during protein extraction and click reactions, conditions known to block antimalarial action of the endoperoxides (17, 18). Nevertheless, to definitively rule out this possibility and validate the results more stringently, we have also introduced the bioorthogonal copper-free click methodology by preparation of the azide analog of the alkyne probe (P2) (Fig. 1). After the azide probe is introduced into target biomolecules after peroxide activation, the azide can be tagged with reporter using several selective reactions (19). Here, we used strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition to verify the results obtained from copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) with P1. The critical tagging reagent, a substituted biotin cyclooctyne, possesses ring strain and electron-withdrawing substituents that together promote the [3 + 2] dipolar cycloaddition with azides installed into the P2 molecule as illustrated in Fig. 1B (19). The Cu-free click reaction follows comparable kinetics to the CuAAC click reaction and proceeds within minutes (19, 20). Both P1 and P2 exhibited similar labeling patterns as indicated by pulldown experiments, including 42 identical proteins (Fig. 3A). However, the pulldown experiment with P2 exhibited higher sensitivity compared with P1 (Fig. 2). The higher sensitivity could be attributed to the higher efficiency of the strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction compared with the CuAAC reaction in aqueous media (19, 20). More importantly, samples treated with the nonperoxidic equivalent of P2 (CP2) did not identify any proteins. Moreover, the comparison between samples treated in situ with P2 vs. cellular homogenates did not show any significant qualitative differences in the tagged protein profiles. Additionally, cellular homogenates exposed to P2 with the iron-chelating agent desferoxamine (DFO) (100 μM) showed that ART–protein alkylation was significantly reduced but not completely abolished by chelation (Fig. S3 and Table S1). These data may support a role for a nonferrous activation process. Alternatively, although 100 μM DFO was previously shown to inhibit the antimalarial activity of this class using live parasite (14), incomplete iron chelation remains a possibility under this experimental condition using processed parasite protein homogenate.

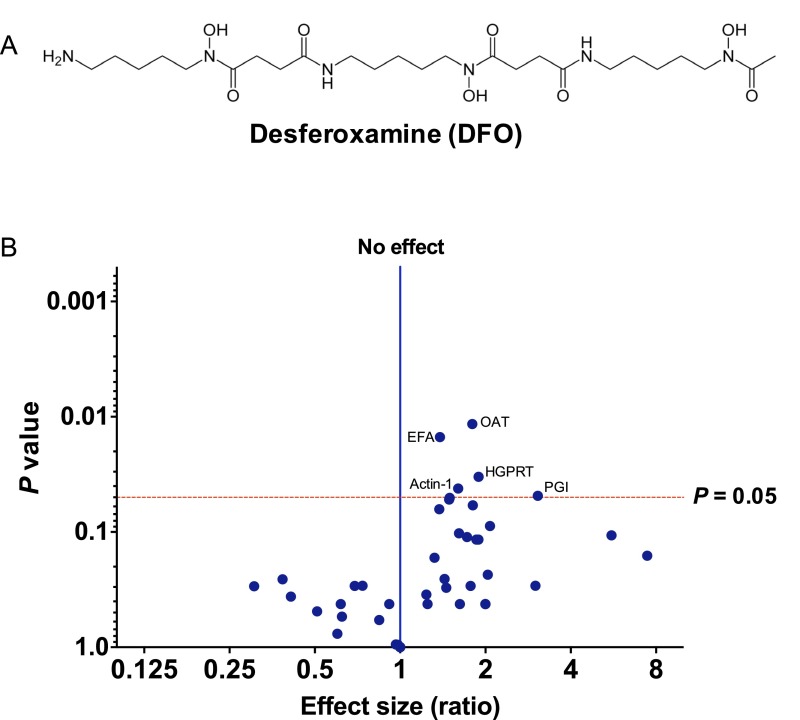

Fig. S3.

Volcano plot illustrating differential protein abundance changes in response to preincubation of P. falciparum 3D7-extracted parasite proteins with the iron-chelating agent DFO. (A) Chemical structure of DFO. (B) Volcano plots with the uncorrected P value plotted against the log twofold change for P2 vs. P2 + DFO. The dotted red line represents P = 0.05; points above the line have P < 0.05, representing significant changes in protein abundance. Proteins of interest in the upper right quadrant (i.e., showing both a more than onefold change in abundance ratio on the x axis and a high statistical significance of P < 0.05 on the y axis) are assigned with abbreviated short names. A detailed description of these proteins and their respective P values is given in Table S1. The complete dataset used to create the volcano plot is in Dataset S4. EFA, elongation factor 1α; HGPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; OAT, ornithine aminotransferase; PGI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase.

Table S1.

List of proteins showing a significant change in abundance after coincubation with DFO at P > 0.05 as measured by multiple t test analysis

| Protein description | P value | Mean emPAI values with P2* | Mean emPAI values with P2 and DFO† |

| Ornithine aminotransferase | 0.0115754 | 13.6 | 7.565 |

| Elongation factor 1α | 0.0150224 | 4.37 | 3.16 |

| Hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase | 0.0332117 | 6.84 | 3.615 |

| Actin-1 | 0.0418945 | 3.27 | 2.04 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 0.0484773 | 0.52 | 0.17 |

emPAI, exponentially modified protein abundance index.

Average of protein abundance (emPAI; n = 2) of the identified proteins with P2 in the absence of DFO.

Average of protein abundance (emPAI; n = 2) of the identified proteins with P2 in the presence of DFO.

Free sulfhydryl groups (thiols) of cysteine residues in the proteins of Plasmodium parasites are sensitive to oxidation and alkylation by ART-derived radicals, generating cysteine adducts (21, 22). Kehr et al. (23) showed that the free thiols in cysteine are reversibly glutathionylated, forming blended protein glutathione disulfides. This posttranslational modification is believed to function primarily as a redox-sensitive switch to facilitate redox regulation and signal transduction (23). Metaanalysis on the protein list identified by ART-ABPPs (P1 and P2) looking for a glutathione binding motif (Fig. 3B) indicated a high positive correlation (χ2 = 230.1 with a P value < 0.0001) as shown in Fig. 2. This positive correlation may be explained by the availability of free thiol groups in cysteine residues acting as targets for ART–protein alkylation. In particular, thiol alkylation may directly contribute to the observed specific inhibition of cysteine proteases and aspartic proteases by the endoperoxides that results in decreased hemoglobin degradation in the parasite’s food vacuole (24).

Interaction of ART with the P. falciparum Hemoglobin Digestion Pathway.

In this study, ART-ABPPs labeled a substantial number of proteases from the parasite’s digestive food vacuole (Fig. 2, Fig. S4, and Table S2). Plasmepsin-2, in particular, was identified in the high confidence list of the ART proteome. Together with plasmepsin-1, these two proteins belong to the aspartic proteases that coordinate with cysteine proteases (falcipain-2 and falcipain-3) in the process of hemoglobin degradation in the parasite’s food vacuole (25–27) and are considered good drug targets (28). Inhibition of vacuolar digestion could contribute to the pleiotropic action of the ART drug class. Neither falcipain-2 nor falcipain-3, considered to be the activators of plasmepsins (29), was targeted by the ART-ABPPs, which may reflect the steric effect of the ART structure in selective binding of aspartic proteases involved in hemoglobin digestion. It also suggests that the targeting of proteins is not promiscuous. However, neither plasmepsin-2 nor M1-family alanyl aminopeptidase, which identified with high confidence by ART-ABPPs, was significantly affected by the iron-chelating agent (DFO), suggesting that the alkylation and inhibition of proteases with ART may not be solely dependent on free Fe+2 (Fig. S3). This observation requires additional investigation. The observation that ART-ABPPs target multiple components of this degradation pathway is credible evidence of ART activation and may implicate disturbance in the parasites feeding process as an important aspect of drug action (Fig. S4) as indicated by work using alternative approaches (7, 30–32).

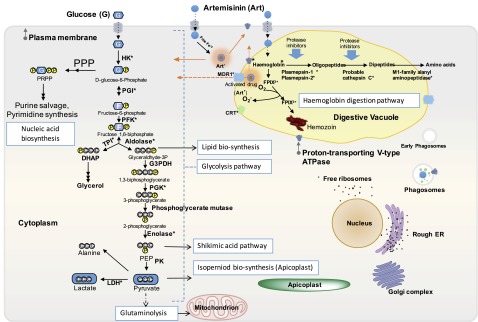

Fig. S4.

Diagram of the main pathways targeted by ART-ABPPs in P. falciparum blood-stage trophozoites. The hemoglobin digestion pathway provides the amino acids to support rapid development and growth of the malaria parasite. Glycolysis provides the primary carbon sources and energy supply for the malaria parasites. Rapid glycolytic flux maintains rate-limiting glycolytic intermediates to support nucleotide biosynthesis, lipid biosynthesis, shikimic acid pathway, isoprenoid biosynthesis, and glutaminolysis. Arrows indicate metabolic steps, with multiple arrows showing various intervening steps not shown; dotted arrows indicate biochemical transport. CRT, chloroquine resistance; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G3PDH, glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase; HK, hexokinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDR, multidrug resistance pump; P, phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PFK, phosphofructokinase; PGI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; PK, pyruvate kinase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase. *Proteins detected and identified by ART-ABPPs. Modified from refs. 41 and 63.

Table S2.

Proteins identified with ART-ABPPs grouped into major metabolic pathways

| Gene identification | Product description | Hits | Average emPAI* | GSH binding† |

| Hemoglobin digestion pathway | ||||

| PF3D7_1408000 | Plasmepsin II | 7 | 0.33 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1407900 | Plasmepsin I | 3 | 0.09 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1116700 | Cathepsin C, homolog, dipeptidyl aminopeptidase 1 | 4 | 0.13 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0207600 | Serine repeat antigen 5 | 3 | 4.31 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1311800 | M1-family alanyl aminopeptidase | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| Antioxidant defense proteins/chaperonin family | ||||

| PF3D7_0917900 | Heat shock protein 70 | 7 | 6.55 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1434300 | Heat shock protein 70/Heat shock protein 90 organizing protein | 3 | 0.02 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0818900 | Heat shock protein 70 | 9 | 3.36 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0608800 | OAT | 9 | 6.16 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1357000 | Elongation factor 1α | 9 | 2.53 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1246200 | Actin I (ART-based therapy 1) | 9 | 1.78 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0903700 | α-Tubulin 1 | 9 | 0.44 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1008700 | Tubulin β-chain | 4 | 0.46 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0503400 | Actin-depolymerizing factor 1 | 4 | 1.05 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0308200 | TCP-1/cpn60 chaperonin family, putative | 7 | 0.22 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1232100 | 60-kDa chaperonin | 7 | 0.10 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0708400 | Heat shock protein 90 | 6 | 0.44 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0923800.2 | Thioredoxin reductase | 4 | 0.05 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0824600 | Fe-S cluster assembly protein DRE2, putative | 4 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Glycolysis pathway | ||||

| PF3D7_1324900 | L-lactate dehydrogenase | 9 | 6.10 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0624000 | Hexokinase | 6 | 0.70 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1015900 | Enolase | 6 | 2.28 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0922500 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 6 | 2.48 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1444800 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 5 | 0.55 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1436000 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) | 4 | 0.21 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1439900 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 4 | 0.13 | 1 |

| Nucleic acid biosynthesis | ||||

| PF3D7_0417200 | Bifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase | 4 | 0.04 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1012400 | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase | 8 | 5.66 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1354500 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | 5 | 0.09 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1405600 | Ribonucleotide reductase small subunit | 4 | 0.14 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0923800.2 | Thioredoxin reductase | 4 | 0.05 | 1 |

| Protein biosynthesis | ||||

| PF3D7_0322900 | 40S ribosomal protein S3A, putative | 9 | 0.38 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1026800 | 40S ribosomal protein S2 | 8 | 0.54 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1130200 | 60S ribosomal protein P0 | 9 | 0.33 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0309600 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 | 7 | 2.04 | 1 |

| Transport proteins | ||||

| PF3D7_1311900 | Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit a | 9 | 0.65 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0406100 | Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit b | 6 | 0.13 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0106300 | Calcium-transporting ATPase | 3 | 0.41 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1117700 | GTP binding nuclear protein RAN/TC4 | 9 | 1.20 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0523000 | Multidrug resistance protein | 6 | 0.38 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1020900 | ADP ribosylation factor | 4 | 0.96 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0709000 | Chloroquine resistance transporter | 3 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Parasite–host cell invasion and the host immune responses | ||||

| PF3D7_0930300 | Merozoite surface protein 1 | 9 | 0.74 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0102200 | Ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen | 6 | 0.03 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1121600 | Circumsporozoite-related antigen, exported protein 1 | 6 | 1.23 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0818900 | Heat shock protein 70 | 9 | 3.36 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1228600 | Merozoite surface protein 9 | 5 | 0.11 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1361900 | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | 5 | 0.17 | 1 |

| PF3D7_1035200 | S antigen | 4 | 0.06 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0207600 | Serine repeat antigen 5 | 3 | 4.31 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0500800 | MESA | 3 | 0.35 | 0 |

emPAI, exponentially modified protein abundance index.

Average emPAI values for each protein.

Glutathione (GSH) binding motif manually identified in each protein according to the work by Kehr et al. (23).

Interaction of ART with P. falciparum Antioxidant Defense Systems.

Hemoglobin digestion in the malaria parasite is a highly dynamic catabolic process. Hemoglobin digestion leaves the parasite under intense oxidative stress by generating active redox byproducts, including heme and a superoxide anion radical (), with the latter being rapidly converted to H2O2 (33). To cope with such highly cytotoxic processes, the parasite recruits an efficient enzymatic antioxidant defense system that includes glutathione and many thioredoxin-dependent proteins. Of particular interest in this study is the labeling of ornithine aminotransferase (OAT), a thioredoxin-dependent protein identified with ART-ABPPs in high confidence and high abundance (Fig. 2 and Table S2). PfOAT is essential in the coordination of ornithine homeostasis, polyamine synthesis, proline synthesis, and mitotic cell division (34). In malaria parasites, PfTrx1 regulates PfOAT redox activity by interaction with two highly conserved cysteine residues (Cys154 and Cys163), which do not exist in any other species and may interfere with substrate binding (34). PfOAT labeling was significantly reduced after iron chelation (Fig. S3), suggesting the supportive role of free iron in drug activation and leading to irreversible binding to PfOAT.

ART itself can generate ROS in the parasite through endoperoxide bridge activation (8, 35), and free Fe+2 can enhance the generation of ROS by the Fenton process (35). Therefore, it has been presumed that ART-activated ROS may lead to parasite death by overwhelming the parasite’s antioxidant defense systems (36). Identification of stress-related proteins (Table S2) by ART-ABPPs supports the hypothesis that ART is involved in the activation and generation of ROS in vivo. Apart from Actin 1, none of these proteins were significantly affected by iron chelation under the condition used here (Fig. S3).

Interaction of ART with the P. falciparum Glycolysis Pathway.

Previous work by our group showed that artemether, the methyl derivative of ART, negatively alters some key glycolytic enzymes while increasing the expression of stress response proteins after pharmacologically relevant drug exposure in the P. falciparum (37). Increased levels of stress-associated proteins coupled with a decrease in glycolytic enzymes suggest a mechanism where the parasite designates to protect its machinery for generating its energy supply from disruption by endoperoxides. This hypothesis is further supported by the recent study, where ART-resistant parasites exhibited a slower growth rate through the early ring stage of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle (38). A credible explanation of this phenomenon, observed in ART-resistant parasites, is that slowing down growth at ring stage by closing down aspects of energy production is a protective mechanism, whereas the parasite experiences ART-induced stress and possible protein damage. Normal growth resumes after up-regulation of the unfolded protein response pathways that are capable of resolving protein damage caused by ART (38). Interestingly, in this study, of 11 enzymes participating in glycolysis, 7 enzymes were labeled and detected with ART-ABPPs (Table S2). The disruption of the microassembly of glycolysis in the parasite by ART should lead to the parasite death. In support of this observation, studies in Schistosoma japonicum-infected mice exposed to artemether also showed an effect of drug treatment on important glycolytic enzymes in the parasite (39, 40). In general, these findings are consistent with the vital and essential role that glycolytic enzymes play in supporting rapid growth and proliferation, similar to that seen in other rapidly proliferating cells, such as cancer cells (41, 42). The high glycolytic flux of intraerythrocytic developmental cycle maintains rate-limiting glycolytic intermediates to support other pathways (e.g., nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis) (Fig. S4) (41).

Overall, apart from glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, none of the glycolytic proteomes identified by ART-ABPPs were significantly affected by iron chelation using cellular homogenate (Fig. S3).

Interaction of ART with P. falciparum Nucleic Acid and Protein Biosynthesis Pathways.

Plasmodium parasites cannot synthesize purine nucleotides de novo and instead, rely on the purine salvage pathway that is essential for parasite growth and survival (43) and has been exploited as a drug target. ART-ABPPs identified five enzymes (Table S2) involved in purine and pyrimidines synthesis (nucleic acid biosynthesis). Many of the enzymes involved in Plasmodium nucleic acid biosynthesis differ from those of their human hosts. Accordingly, nucleic acid biosynthesis pathways have long been considered exploitable targets for novel antimalarial drug design (43–46). For example, P. falciparum bifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase mediates the conversion of dihydrofolic acid (dihydrofolate; vitamin B9) to tetrahydrofolic acid by dihydrofolate (44). Tetrahydrofolate is needed to make both purines and pyrimidines, the building blocks of DNA and RNA, and some of our most successful antimalarials, such as pyrimethamine and proguanil, target this enzyme, resulting in parasite death (44, 47). Furthermore, P. falciparum hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase, an ART-ABPPs target identified with high confidence, is also central in purine salvage (46). Labeling of the P. falciparum hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase was significantly reduced after iron chelation (Fig. S3), suggesting a role of chelatable iron in ART activation leading to alkylation of the enzyme. ART-ABPPs also identified many ribosomal proteins (Table S2), suggesting that protein synthesis is an additional target for ART.

Interaction of ART with P. falciparum Chaperone Proteins and the Cytoskeleton.

ART-ABPPs identified several chaperone proteins (Table S2). The majority of chaperonins were initially identified as heat shock proteins expressed in parasites in response to elevated temperatures, a prominent symptom of the disease, and/or other cellular stresses. In general, molecular chaperones are involved in many cellular functions, including helping newly synthesized proteins to fold, protein trafficking, and signal transduction (48). TCP-1 and cytoskeletal proteins α-tubulin, β-tubulin, and actin 1 were all labeled by ART-ABPPs. The fact that actin and tubulin folding and dimerization are chaperoned by the TCP-1 chaperonin system gives rise to suggest a potential link between ART, the parasite cell structure, protein trafficking systems, and signal transduction.

Interaction of ART with Transport Proteins in P. falciparum.

ART-ABPPs identified the two subunits of the V-type H+-ATPase (subunits A and B) at various levels of confidence from high to medium, respectively (Table S2). In the parasite, a V-type ATPase generates a proton motive force across the parasite plasma membrane as well as across the digestive food vacuole (49, 50). It has previously been shown that ART results in rapid depolarization of the parasite plasma membrane (51). Although the depolarization of the plasma membrane was previously shown to be partially attributed to lipid peroxidation, the ART-ABPPs data presented here could be interpreted as showing the potential for a direct inhibition of the V-type ATPase activity by ART. Structural similarity between ARTs and thapsigargin, an inhibitor of SERCA (PfATP6), led to a hypothesis that PfATP6 was a target for ART (5). This proposal received additional support from a study connecting ART resistance in P. falciparum field isolates from French Guiana with the S769N mutation in PfATP6 (52). The functional importance of PfATP6 in ART action and resistance remains controversial; however, PfATP6 was detected by the alkyne version of ART-ABPPs (P1), albeit at low yield and low confidence. In addition to metabolic pathways, ART-ABPPs identified nine proteins related to parasite–host cell invasion and the host immune responses (Table S2). The functional relevance of these as targets remains to be tested.

ART and Resistance Mechanisms in P. falciparum.

Several genes have been associated with ART resistance mechanisms, including the chloroquine resistance gene (Pfcrt), the multidrug resistance pump (Pfmdr1), and the K13 propeller domain of the kelch-like protein (2, 38, 53). This study was not designed to probe resistance, and only a single parasite isolate has been investigated; however, the gene products of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 (Table S3), and a protein from the proteasomal system, Cdc48 protein (but not K13), were labeled with ART-ABPP. These findings indicate the potential for the use of ART-ABPPs in investigating resistance and tolerance mechanisms using appropriate parasite isolates with well-defined resistance phenotypes.

Table S3.

Proteins identified with ART-ABPPs relevant to drug resistance

| Gene identification | Product description | Hits | Average emPAI* | GSH binding† |

| PF3D7_0523000 | Multidrug resistance protein | 6 | 0.38 | 1 |

| PF3D7_0709000 | Chloroquine resistance transporter | 3 | 0.18 | 0 |

| PF3D7_0106300 | Calcium-transporting ATPase | 3 | 0.41 | 0 |

| PF3D7_1012400 | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase | 8 | 3.18 | 1 |

emPAI, exponentially modified protein abundance index.

Average emPAI values for each protein.

Glutathione (GSH)-binding motif manually identified in each protein according to the work by Kehr et al. (23).

ART Interactome.

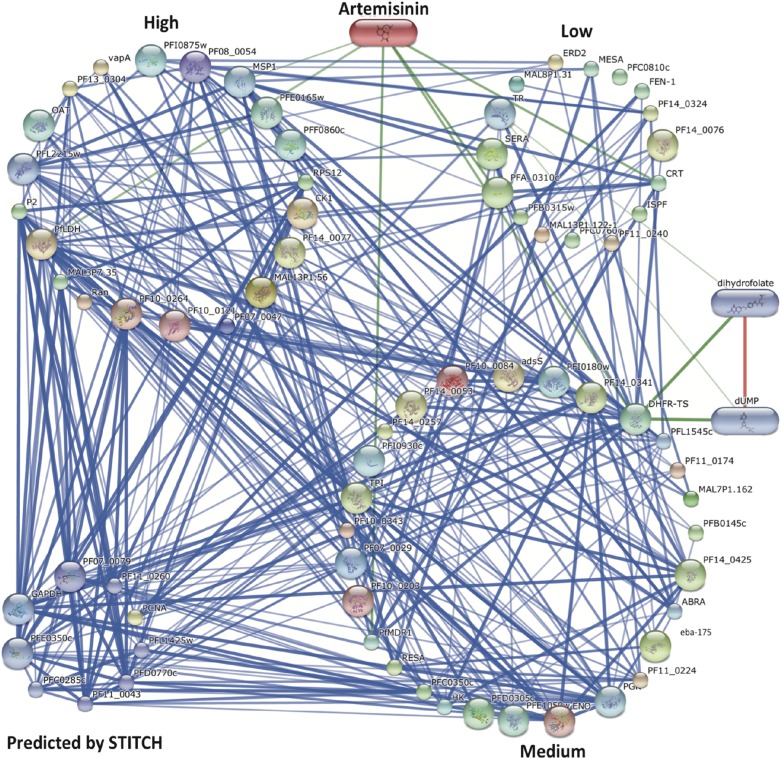

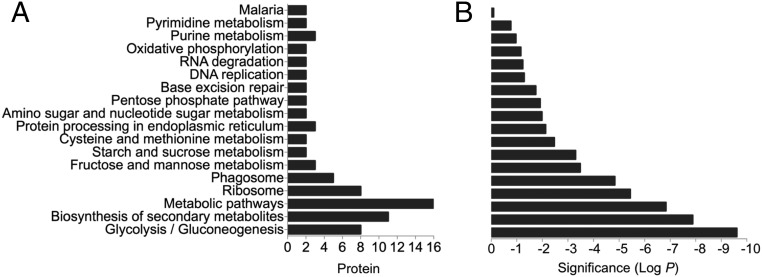

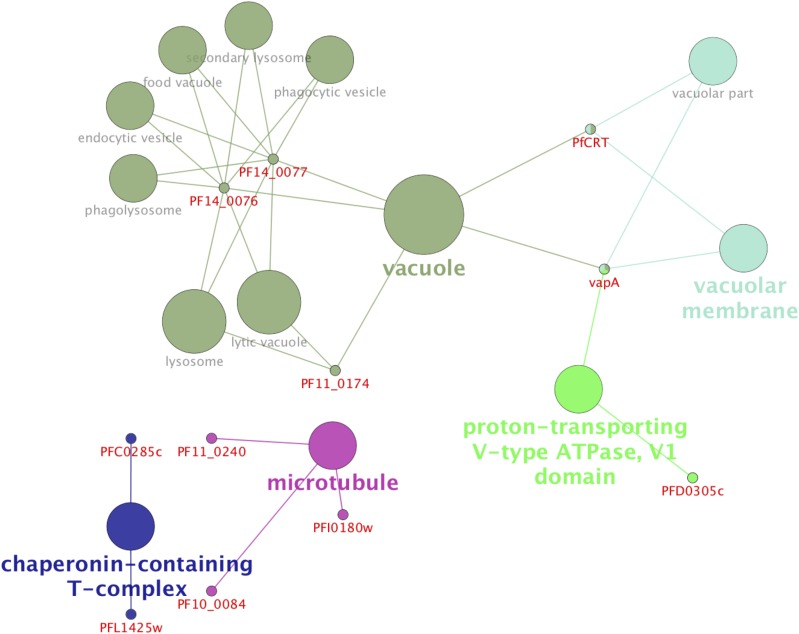

We used a bioinformatics interaction network analysis approach using STICH 4 software (54) to build up and predict functional ART–protein association networks and identify major pathways targeted by the drug based on compiled available experimental evidence, database information, and the literature. Analysis of the data generated in silico connectivity for ART, with 67 proteins collectively identified with P1 and P2 termed the ART interactome shown in Fig. S5. As predicted, the proteome experimentally identified with ART-ABPPs revealed a strong network association of functionally important proteins (Fig. S5). The connectivity analysis confirmed that the glycolytic pathway is a primary interacting target for ART with a P value of 1 × 10−9 (Fig. 4). Additional pathways were identified as being targets for ART interaction, including the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, metabolic pathways, ribosomes, phagosomes, etc. (Fig. 4). Additional analysis to identify the cellular components targeted by the ART interactome using Cytoscape software supports a role for ART acting akin to the “cluster bomb” hypothesis (55), with multiple cellular targets mainly but not exclusively in the food vacuole and cytosol (Figs. S4 and S6). The important next step will be to establish which of these interactions has functional relevance regarding parasite lethality and resistance.

Fig. S5.

The confidence view of the ART–protein and protein–protein interaction network. The ART interactome was map built using the STITCH 4 web tool (stitch.embl.de) with default parameters and the accession codes for identified proteins. Proteins clustered into three main groups according to the confidence criteria explained in the text (Fig. 2). Predicted proteins using the protein–protein interaction analysis function were grouped by STITCH. Thicker lines represent stronger associations, protein–protein interactions are shown in blue, chemical–protein interactions are shown in green, and interactions between chemicals are shown in red. Network interaction analysis details can be found in Dataset S2.

Fig. 4.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis for biological pathways identified from ART proteome. (A) Black bars represent the numbers of proteins identified within each biological process (pathway) using the STITCH 4 web tool (stitch.embl.de). (B) Multiple testing corrected P values for enriched GO categories. The confidence view of ART–protein and protein–protein interactions networks built up using the STITCH 4 web tool is illustrated in Fig. S4. A complete dataset of ART interactome is in Datasets S2 and S3.

Fig. S6.

ART-ABPPs targeted proteins throughout the parasite, including proteins from the cytosol and the parasites food vacuole as identified by Gene Ontology analysis using Cytoscape software version 3.3.0 (64) and CluGO App (65).

Conclusion and Future Perspective.

Using a chemical proteomic approach, we have identified with a high level of confidence key proteins that are alkylated by ART; the biological functions of the tagged proteins are consistent with many of the presumed mechanisms proposed to explain ART drug action, in which the ART causes extensive damages to key proteins that have a wide spectrum of cellular activity. Collectively, copper-based and copper-free ART-ABPPs approaches present significant evidence in support of the argument that ART can target two important sources of carbon/energy and amino acid supply (i.e., glycolysis and hemoglobin digestion pathways) within the erythrocytic stage of infection. ART-ABPPs also provide additional evidence that ART targets other essential parasite metabolic pathways, including DNA synthesis, protein synthesis, and lipid synthesis. The application of ART-ABPPs to monitor the activity of protein target(s) as well as their abundance in different parasite lines could have significant implications for understanding the problem of ART resistance, especially combined with genomic approaches. The data generated here are a significant step forward in identifying the complete array of protein targets that are susceptible to alkylation with ART. The next key step will be to define formally which of these alkylation reactions is functionally most relevant to antimalarial drug action and which may be modified to confer drug resistance.

Methods

Synthesis of Endoperoxide Probes and Respective Controls.

Endoperoxide probes and corresponding deoxy ether analogs (controls) were synthesized as detailed in SI Text.

Parasite Cultures and Drug Sensitivity Assays.

P. falciparum 3D7 parasites were cultured following the method illustrated in SI Text. Drug activities of ART-ABPPs were measured using a standard fluorometric DNA binding method as detailed in SI Text.

In Situ Parasite Treatment for Chemical Proteomic Pulldown Assays.

Ten flasks of synchronized trophozoite-stage parasite cultures at 10–12% parasitemia and 4% hematocrit (0.5 L culture) were treated with ART-ABPPs P1 and P2 and their respective controls (100 μL 5 mM stock) to give a final concentration of 1 μM probe per treatment, 10-fold the IC90 (100 nM) at short pulse time to ensure full inhibition of parasite growth and maximal alkylation (53). All treatments were carried out with a minimum of two replicates per treatment (noted elsewhere). Probe-treated parasites were maintained in culture at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 3% CO2, 4% O2, and 93% N2 for 6 h, an incubation period that has already been shown to cause irreversible parasite lethality (53). An equivalent culture without drug probe (five replicates) was treated with 100 μL DMSO as a control treatment maintained under identical culture conditions. Parasite proteins were sequentially extracted using a modification of the protocol described by Molloy et al. (56) (SI Text).

ART-ABPPs Labeling and the Effect of Iron Chelation.

Parasite protein extracts (cellular homogenates) were prepared from 1 L untreated in vitro cultured parasite as described earlier. Protein extracts were adjusted to 2 mg/mL in Eppendorf tubes and treated with P2 at 10 μM in the presence or absence of the iron-chelating agent DFO at 100 μM for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequent protein processing was as described in SI Text.

Identification of ART-ABPPs Alkylated Proteins.

Alkylated proteins from all experiments were subjected to click chemistry reaction with relevant biotin reporter as detailed in SI Text. As the next step, biotin-tagged proteins was affinity-purified using streptavidin agarose beads, and the captured proteins was identified using LC-MS/MS after bead trypsin digestion for the purified proteins as described in SI Text.

SI Text

Synthesis and Analysis of Click Probes.

General coupling procedure 1.

To a stirring solution of carboxylic acid (50 mg, 0.15 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide⋅HCl (50 mg, 0.24 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (19 mg, 0.17 mmol). After activating for 1 h, either amine azide or amine alkyne (38 mg, 19 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was added to the solution. After 24 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel; 20:80 EtOAc:n-Hex), giving the desired product as colorless crystals.

|

10β-(Acetamidomethylalkyne)deoxoartemisinin P1.

Synthesis achieved using general procedure 1 to give the title compound (38 mg, 69%) as colorless crystals.

P1: Rf = 0.65, 60% ethyl acetate in hexane; melting point = 129–130 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ5.39 [1H, singlet (s)], 4.82 [1H, doublet of doublets (ddd), J = 11.3, 6.2, 1.7 Hz], 4.06 (2H, dd, J = 5.2, 2.6 Hz), 2.60–2.48 [2H, multiplet (m)], 2.41–2.28 (2H, m), 2.19 [1H, triplet (t), J = 2.6 Hz], 2.07 (1H, ddd, J = 14.6, 4.4, 3.2 Hz), 2.03–1.94 (1H, m), 1.84–1.71 (2H, m), 1.71–1.61 (2H, m), 1.44 (3H, s), 1.42–1.11 (5H, m), 0.98 [3H, doublet (d), J = 5.9 Hz], and 0.87 (3H, d, J = 7.6 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), δ171.6, 103.1, 90.5, 81.0, 79.9, 71.4, 69.2, 51.8, 43.4, 37.7, 37.5, 36.7, 34.3, 30.6, 29.1, 26.0, 25.0, 25.0, 20.1, and 12.0; IR \x{03bd}max (neat)/cm−1, 3359, 3286, 2976, 2948, 2921, 2858, 1675, 1522, 1454, 1425, 1383, 1362, 1346, 1316, 1268, 1232, 1203, 1185, 1147, 1126, 1089, 1072, 1044, 1026, 1013, 995, 957, 939, 911, 878, 841, 822, 737, 691, 665, and 608; high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) [electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI)] calculated for C20H29NO5 [M + Na]+ 386.1943 found 386.1942; microanalysis calculated for C20H29NO5 requires C 66.09%, H 8.04%, N 3.85%, found C 65.97%, H 8.01%, N 3.72%.

|

Synthesis of 3-azido-1-propylamine (C1).

To a stirred solution of 3-chloropropylamine hydrochloride (2.2 g, 17 mmol) in water (20 mL), sodium azide (3.4 g, 48 mmol) was added, and the solution was heated to 80 °C. After 15 h, the solution was cooled and basified (KOH). EtOAc (20 mL) was added, and the organic layer was extracted (3 × 15 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, and solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was contaminated with starting material; therefore, flash-column chromatography (20–40% EtOAc/Hex) was necessary to obtain the pure product as a colorless oil (0.5 g, 29%).

C1: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ3.40 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, CH2N3), 2.87–2.83 (2H, m, CH2NH2), 1.86 [2H, broad singlet (br s), NH2], 1.81–1.74 (2H, m, CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 49.4 (C-N3), 39.5 (C-NH2), 32.0 (CH2); HRMS [chemical ionization (CI)] 101.1, [M + H]+ requires 101.1.

|

10β-(Acetamidopropylazide)deoxoartemisinin P2.

Synthesis was achieved using general procedure 1 to give the title compound (44 mg, 80%) as colorless crystals.

P2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ5.38 (1H, s, 12-H), 4.76 [1H, doublet of triplets (dt), J = 7.9 and 6.1 Hz, 10-Hα], 3.48–3.20 (4H, m, HN-CH2 and H2C-N3), 2.59–1.61 (17 H), 1.33 (3H, s, 3-CH3), 0.96 (3H, d, J = 5.8 Hz, 9-CH3), 0.88 (3H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, 6-CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ172.2 [carboxyamide (CONH)], 103.3 (C-3), 90.6 (C-12), 81.2, 70.0, 52.1, 49.5, 43.7, 37.9, 37.8, 36.9, 34.5, 30.8, 29.2, 26.2, 25.2 (3-CH3), 20.3 (6-CH3), 12.4 (9-CH3); HRMS (ESI); 431.2274 [M + Na]+ C20H32N4O523Na requires 431.2270. C20H32N4O5 requires C of 58.81%, H of 7.90%, and N of 13.72% and found C of 58.58%, H of 7.89%, and N of 13.20%.

|

10β-Deoxy-(methylester)-deoxoartemisinin (C2).

Zinc dust (1 g) was activated by washing with 5% (vol/vol) aqueous HCl (3 × 10 mL), water (3 × 10 mL), and diethyl ether (3 × 10 mL) and then, thoroughly dried in vacuo. Activated zinc dust (50 mg) was added to a stirring solution of ester (200 mg, 0.67 mmol) in glacial acetic acid (35 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 72 h, with more zinc dust added at 24 and 48 h, respectively. After 72 h, CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a sintered glass funnel and washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 mL). The filtrate and washings were combined and neutralized with NaHCO3. The organic layer was separated and washed with NaHCO3 (25 mL), brine (25 mL), and water (25 mL); it was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by column chromatography (40:60 EtOAc:n-Hex) afforded C2 (105 mg, 56%) as a colorless oil.

C2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ5.17 (1H, s, H-12), 4.60–4.54 (1H, m, H-10), 3.63 (3H, s), 3.78–3.75 (2H, m), 3.46–2.23 (3H, m), 1.92–1.51 (10H, m), 1.49 (3H, s, 3-CH3), 0.82 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, 9-CH3), and 0.79 (3H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, 6-CH3).

|

10β-Deoxy-(carboxylic acid)-deoxoartemisinin C3.

To a solution of C2 (150 mg, 0.46 mmol) in EtOH (95%), NaOH (15%) was added and the reaction was allowed to stir for 3 h. The solution was acidified with 1.0 M aqueous HCl, ethanol was removed, and water (10 mL) was added to the residue. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give 28 (100 mg, 92%) as a colorless brittle solid.

C3: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ8.50 [1H, br s, carboxylic acid (COOH)], 5.20 (1H, s, 12-H), 4.57 (1H, dt, J = 7.5, 6.0 Hz, 10-Hα), 4.05 (1H, dt, J = 7.5, 6.0 Hz, CH), 2.50 (1H, dd, J = 15.0, 3.5 Hz, 8-Hα), 2.32 (1H, dt, J = 14.0, 4.0 Hz, 9-Hα), 1.92–1.52 (5H, m), 1.48 (3H, s, CH3), 1.24–1.10 (6H, m), 0.97–0.95 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, 9-CH3), 0.89–0.87 (3H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, 6-CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ176.9 (COOH), 108.1 (C-3), 89.6 (C-12), 82.9 (C-5), 71.8 (C-10), 52.5, 37.7, 36.8, 36.4, 36.2, 34.7, 30.2, 26.2, 25.1, 25.0 (3-CH3), 20.4 (6-CH3), 13.2 (9-CH3); IR (neat) per centimeter−1; 3,500–2,500 (OH) 2,925 (C-H), 1,711 (C = O), 1,377, 876 (O-O), and 832 (O-O); HRMS (CI); 333.1678 [M + Na]+; C17H26O523Na requires 333.1674.

|

CP1: Synthesis was achieved using general procedure 1 to give the title compound (10 mg, 45%) as colorless crystals.

CP1: Rf = 0.34, 50% ethyl acetate in hexane; melting point = 119–120 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ6.98 (1H, s), 5.32 (1H, s), 4.54 (1H, ddd, J = 10.0, 6.9, 3.1 Hz), 4.06 (2H, ddd, J = 17.5, 7.4, 5.4, 2.5 Hz), 2.40–2.37 (1H, m), 2.31–2.21 (1H, m), 2.19 (1H, t, J = 2.5 Hz), 1.99 (1H, ddd, J = 13.1, 8.7, 4.1 Hz), 1.93–1.86 (1H, m), 1.85–1.77 (1H, m), 1.76–1.67 (2H, m), 1.66–1.56 (1H, m), 1.55 (3H, s), 1.36–1.11 (6H, m), 0.91 (3H, d, J = 5.9 Hz), and 0.87 (3H, d, J = 7.6 Hz); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3), δ171.5, 107.9, 97.3, 82.7, 80.0, 71.1, 65.2, 45.3, 39.9, 38.1, 35.7, 34.5, 29.7, 28.9, 25.4, 23.8, 22.3, 18.9, and 11.9; IR \x{03bd}max (neat)/cm−1, 3358, 3318, 2962, 2932, 2875, 1683, 1527, 1461, 1440, 1421, 1389, 1348, 1315, 1298, 1262, 1246, 1211, 1191, 1174, 1140, 1123, 1108, 1076, 1043, 1007, 980, 939, 929, 894, 868, 856, 720, 686, 655, and 610; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C20H29NO4 [M + Na]+ 348.2175 found 348.2177; microanalysis calculated for C20H29NO4 requires C 69.14%, H 8.41%, N 4.03%, found C 67.84%, H 8.41%, N 3.91%.

|

CP2: Synthesis was achieved using general procedure 1 to give the title compound (12 mg, 32%) as colorless crystals.

CP2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ6.83 (1H, br s, CONH), 5.31 (1H, s, 12-H), 4.50 (1H, dt, J = 7.5, 6.0 Hz, 10-Hα), 3.46–3.37 (3H, m, CH, CH2), 3.31–3.24 (1H, m, CH), 2.44–2.22 (3H, m), 2.02–1.57 (7H, m), 1.52 (3H, s, CH3), 1.30–1.16 (6H, m), 0.97–0.95 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, 9-CH3), 0.89–0.87 (3H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, 6-CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ172.3 (CONH), 108.1 (C-3), 97.5, 82.9 (C-5), 65.8 (C-10), 49.3, 45.5, 40.1, 38.6, 36.0, 34.8, 30.0, 29.2, 25.6 (3-CH3), 24.0, 22.5, 19.1 (6-CH3), 12.2 (9-CH3); [M + Na]+ 415.2312; C17H26O523Na requires 415.2321. C20H32N4O4 requires C of 61.20%, H of 8.22%, and N of 14.27% and found C of 60.84%, H of 8.19%, and N of 13.95%.

Parasite cultures.

Plasmodium falciparum (3D7 strain) parasites were cultured following the method in work by Trager and Jensen (57) with minor modifications. The cultures consisted of a 4% (vol/vol) suspension of O+ erythrocytes in RPMI medium 1640 (R8758, glutamine, and NaHCO3) supplemented with 10% pooled human AB+ serum, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), and 20 μM gentamicin sulfate. Parasite cultures were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 3% CO2, 4% O2, and 93% N2. Parasite growth was synchronized by treatment with sorbitol (58). The culture was evaluated for parasitemia and parasite stages daily by microscopy of Giemsa-stained thin blood films.

Drug sensitivity assays.

Antimalarial activities of probes were evaluated using a standard fluorometric DNA binding method (59). Assay plates were created in a 96-well format using a Hamilton Star robotic platform. Probe concentrations ranged from 0.122 nM to 2 μM, with 1 μM ART used as a positive control. Parasite inoculum was 0.5% parasitemia (ring stage) at 1% hematocrit. Parasites were incubated with the test compound for 48 h in standard culture conditions. At 48 h, 100 μL SYBR Green (I) in lysis buffer (0.2 μL SYBR Green I per 1 mL lysis buffer) was added to each well, and parasite growth was assessed based on fluorescent DNA staining monitored at 490/520-nm excitation/emission wavelengths relative to drug-free control well values. The IC50 was calculated using the log of the dose–response relationship as fitted with Grafit software (Erithacus Software). Probes, their respective controls, and ART stock solutions (5 mM) were prepared in DMSO. The results are given as the means of at least three separate experiments.

Preparation of parasite protein extract for click chemistry.

Parasite proteins were extracted from ART-ABPP–treated and –untreated parasite cultures using a modification of the protocol described by Molloy et al. (56). Serum proteins were removed by three washes with sterile Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Dulbecco’s PBS (D-PBS; pH 7.4; Invitrogen) containing sorbitol (250 mM sorbitol) followed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The parasites were released from infected erythrocytes by saponin lysis (0.15% wt/vol in D-PBS–buffered sorbitol) for 10 min on ice and then, washed three times with ice-cold D-PBS–buffered sorbitol followed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min to sediment parasites and red cell membrane debris. Parasite pellets were stored at −80 °C until protein extraction. In all experiments, proteins were extracted by subjecting the parasite to three cycles of freeze–thaw in D-PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM DTT, 1% Nonidet P-40 (Nonidet P-40; Sigma-Aldrich), and a protease inhibitor mixture (cOmplete EDTA-Free Protease Inhibitor Mixture; Roche) followed by trituration with a sonicator probe on ice (∼4 °C). The PBS-soluble fraction was then separated (10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min), and the supernatant was stored at −80 °C for later use. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (60).

Click chemistry.

In all experiments, P. falciparum protein extracts were adjusted to 2 mg/mL by diluting the protein extract in D-PBS in a total volume of 1 mL. Each sample was split into two aliquots (500 μL each), and the click reaction was initiated by addition of the reporter under the relevant click chemistry conditions. For samples treated with the alkyne probe, biotin azide (Invitrogen) was used as the reporter in the presence of reduced copper as a catalyst according to conditions optimized by Speers and Cravatt (9). Briefly, biotin azide (5.65 μL 5 mM stock), Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (11.3 μL 50 mM stock), Tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (TBTA) (34 μL 1.7 mM stock), and CuSO4 (11.3 μL 50 mM stock) were added to the sample in that order to provide a final sample of 500 μL. For the 1D gel analysis, biotin azide was replaced with the trifunctional azido-biotin-rhodamine (provided by Benjamin Cravatt, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). For samples treated with azide ART-ABPPs, biotin azide was replaced with 2 μL Click-IT Biotin DIBO Alkyne (Invitrogen), and copper-free click reaction conditions (20) were initiated without the addition of TCEP, TBTA, and CuSO4 (20). An adequate mix was achieved by vortex mixing after adding each component, with the exception of the TCEP step. Reactions were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark with gentle mixing every 15 min. After 1 h, the click reaction was terminated. The respective samples were combined, and protein was precipitated with cold methanol and centrifuged at 6,500 × g for 4 min at 4 °C. The resultant pellets were then washed with 750 μL cold methanol followed by three rounds of sonication (3–4 s). Then, 650 μL 2.5% SDS (Sigma-Aldrich) in D-PBS was added to the samples followed by sonication (3–4 s) to dissolve the remaining pellet. Samples were next heated at 95 °C for 5 min in a heat box with two rounds of sonication (3–4 s). Samples were then centrifuged at 6,500 × g for 4 min, and the supernatants were collected and adjusted to a final volume of 3.5 mL with D-PBS. Samples were then stored at −20 °C for additional processing.

Affinity purification and MS.

After the termination of the click reaction, probe-labeled proteins were enriched and affinity-purified using streptavidin agarose beads. The resultant purified proteins were digested using an on-bead trypsin digestion protocol described previously (61). The resultant tryptic peptides were then subjected to high-resolution MS peptide sequencing using a Thermo Scientific UltiMate 3000LC Chromatography System coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap Velos Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). To increase the accuracy of protein identification, tryptic peptides from each sample were injected into the system in quadruplicate using the reverse-phase LC conditions reported previously (62). Protein identification was performed using the MASCOT search engine with the following parameters in operation: a precursor mass tolerance of 7 ppm and a fragment ion tolerance of 0.3 Da with two tryptic missed cleavages permitted. Carbamidomethyl was set as a static modification with oxidation of methionine and deamidation set as dynamic modifications. A decoy database was searched, and relaxed peptide confidence filters were applied to the dataset [ion scores P < 0.05/false discovery rate (FDR) = 5%].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust through its Strategic Support Fund award, Medical Research Council Confidence in Concept funding, and through Mahidol-Liverpool Chamlong Harinasuta PhD Scholarship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600459113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.WHO . World Malaria Report 2014. WHO; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winzeler EA, Manary MJ. Drug resistance genomics of the antimalarial drug artemisinin. Genome Biol. 2014;15(11):544. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: Final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):31–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60721-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rts SCTP. RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership Efficacy and safety of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine during 18 months after vaccination: A phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in children and young infants at 11 African sites. PLoS Med. 2014;11(7):e1001685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckstein-Ludwig U, et al. Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2003;424(6951):957–961. doi: 10.1038/nature01813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neill PM, Barton VE, Ward SA. The molecular mechanism of action of artemisinin--the debate continues. Molecules. 2010;15(3):1705–1721. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer AE, Copple IM, Maggs JL, O’Neill PM, Park BK. The role of heme and the mitochondrion in the chemical and molecular mechanisms of mammalian cell death induced by the artemisinin antimalarials. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(2):987–996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes RK, et al. Facile oxidation of leucomethylene blue and dihydroflavins by artemisinins: Relationship with flavoenzyme function and antimalarial mechanism of action. ChemMedChem. 2010;5(8):1282–1299. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Profiling enzyme activities in vivo using click chemistry methods. Chem Biol. 2004;11(4):535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail HM, et al. Pyrethroid activity-based probes for profiling cytochrome P450 activities associated with insecticide interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(49):19766–19771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penarete-Vargas DM, et al. A chemical proteomics approach for the search of pharmacological targets of the antimalarial clinical candidate albitiazolium in Plasmodium falciparum using photocrosslinking and click chemistry. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asawamahasakda W, Ittarat I, Pu YM, Ziffer H, Meshnick SR. Reaction of antimalarial endoperoxides with specific parasite proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(8):1854–1858. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Wong VK, Ko BC, Wong MK, Che CM. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of artemisinin derivatives containing lipophilic alkyl carbon chains. Org Lett. 2005;7(8):1561–1564. doi: 10.1021/ol050230o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stocks PA, et al. Evidence for a common non-heme chelatable-iron-dependent activation mechanism for semisynthetic and synthetic endoperoxide antimalarial drugs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(33):6278–6283. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishihama Y, et al. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4(9):1265–1272. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500061-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bousejra-El Garah F, Pitié M, Vendier L, Meunier B, Robert A. Alkylating ability of artemisinin after Cu(I)-induced activation. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14(4):601–610. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0474-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krungkrai SR, Yuthavong Y. The antimalarial action on Plasmodium falciparum of qinghaosu and artesunate in combination with agents which modulate oxidant stress. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81(5):710–714. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meshnick SR, et al. Activated oxygen mediates the antimalarial activity of qinghaosu. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;313:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Bioorthogonal chemistry: Fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(38):6974–6998. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baskin JM, et al. Copper-free click chemistry for dynamic in vivo imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(43):16793–16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu WM, Chen YL, Zhai Z, Xiao SH, Wu YL. Study on the mechanism of action of artemether against schistosomes: The identification of cysteine adducts of both carbon-centred free radicals derived from artemether. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13(10):1645–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Yue ZY, Wu YL. Interaction of qinghaosu (artemisinin) with cysteine sulfhydryl mediated by traces of non-heme iron. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38(17):2580–2582. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990903)38:17<2580::aid-anie2580>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kehr S, et al. Protein S-glutathionylation in malaria parasites. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(11):2855–2865. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey AV, Tekwani BL, Singh RL, Chauhan VS. Artemisinin, an endoperoxide antimalarial, disrupts the hemoglobin catabolism and heme detoxification systems in malarial parasite. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(27):19383–19388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee R, et al. Four plasmepsins are active in the Plasmodium falciparum food vacuole, including a protease with an active-site histidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(2):990–995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022630099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sijwali PS, Rosenthal PJ. Gene disruption confirms a critical role for the cysteine protease falcipain-2 in hemoglobin hydrolysis by Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(13):4384–4389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemba M, Gluzman I, Goldberg DE. A Plasmodium falciparum dipeptidyl aminopeptidase I participates in vacuolar hemoglobin degradation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(41):43000–43007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal PJ, McKerrow JH, Aikawa M, Nagasawa H, Leech JH. A malarial cysteine proteinase is necessary for hemoglobin degradation by Plasmodium falciparum. J Clin Invest. 1988;82(5):1560–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI113766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drew ME, et al. Plasmodium food vacuole plasmepsins are activated by falcipains. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(19):12870–12876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708949200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klonis N, et al. Artemisinin activity against Plasmodium falciparum requires hemoglobin uptake and digestion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(28):11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104063108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Gerhard GS. Heme activates artemisinin more efficiently than hemin, inorganic iron, or hemoglobin. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(16):7853–7861. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meshnick SR, Thomas A, Ranz A, Xu CM, Pan HZ. Artemisinin (qinghaosu): The role of intracellular hemin in its mechanism of antimalarial action. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker K, et al. Oxidative stress in malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes: host-parasite interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34(2):163–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jortzik E, et al. Redox regulation of Plasmodium falciparum ornithine δ-aminotransferase. J Mol Biol. 2010;402(2):445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishna S, Uhlemann AC, Haynes RK. Artemisinins: Mechanisms of action and potential for resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7(4-5):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunt NH, Stocker R. Oxidative stress and the redox status of malaria-infected erythrocytes. Blood Cells. 1990;16(2-3):499–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makanga M, Bray PG, Horrocks P, Ward SA. Towards a proteomic definition of CoArtem action in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proteomics. 2005;5(7):1849–1858. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mok S, et al. Drug resistance. Population transcriptomics of human malaria parasites reveals the mechanism of artemisinin resistance. Science. 2015;347(6220):431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1260403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao S, et al. Effect of artemether on hexokinase, glucose phosphate isomerase and phosphofructokinase of Schistosoma japonicum harbored in mice. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 1998;16(1):25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao SH, et al. Effect of artemether on glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, and pyruvate kinase of Schistosoma japonicum harbored in mice. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1998;19(3):279–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salcedo-Sora JE, Caamano-Gutierrez E, Ward SA, Biagini GA. The proliferating cell hypothesis: A metabolic framework for Plasmodium growth and development. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(4):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olszewski KL, Llinás M. Central carbon metabolism of Plasmodium parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;175(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ting LM, et al. Targeting a novel Plasmodium falciparum purine recycling pathway with specific immucillins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9547–9554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuthavong Y, et al. Malarial dihydrofolate reductase as a paradigm for drug development against a resistance-compromised target. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):16823–16828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204556109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cassera MB, Zhang Y, Hazleton KZ, Schramm VL. Purine and pyrimidine pathways as targets in Plasmodium falciparum. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11(16):2103–2115. doi: 10.2174/156802611796575948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarkar D, Ghosh I, Datta S. Biochemical characterization of Plasmodium falciparum hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphorybosyltransferase: Role of histidine residue in substrate selectivity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137(2):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuthavong Y, et al. Malarial (Plasmodium falciparum) dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase: Structural basis for antifolate resistance and development of effective inhibitors. Parasitology. 2005;130(Pt 3):249–259. doi: 10.1017/s003118200400664x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475(7356):324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi M, et al. Vacuolar H(+)-ATPase localized in plasma membranes of malaria parasite cells, Plasmodium falciparum, is involved in regional acidification of parasitized erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(44):34353–34358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saliba KJ, Kirk K. pH regulation in the intracellular malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. H(+) extrusion via a V-type H(+)-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(47):33213–33219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antoine T, et al. Rapid kill of malaria parasites by artemisinin and semi-synthetic endoperoxides involves ROS-dependent depolarization of the membrane potential. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(4):1005–1016. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jambou R, et al. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in-vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet. 2005;366(9501):1960–1963. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ariey F, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505(7481):50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuhn M, et al. STITCH 4: Integration of protein-chemical interactions with user data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D401–D407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ridley RG. Malaria: To kill a parasite. Nature. 2003;424(6951):887–889. doi: 10.1038/424887a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molloy MP, et al. Extraction of membrane proteins by differential solubilization for separation using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 1998;19(5):837–844. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193(4254):673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979;65(3):418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(5):1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) and click chemistry (CC)-ABPP by MudPIT mass spectrometry. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2009;1:29–41. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch090138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voronin D, et al. Wolbachia lipoproteins: Abundance, localisation and serology of Wolbachia peptidoglycan associated lipoprotein and the Type IV Secretion System component, VirB6 from Brugia malayi and Aedes albopictus. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:462. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0462-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gardner MJ, et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419(6906):498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saito R, et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat Methods. 2012;9(11):1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bindea G, et al. ClueGO: A Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.