Significance

Virtually the entire cortex is innervated by cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain. Traditionally, this neuronal system has been described as a neuromodulator system that supports global states such as cortical arousal. The presence of fast and regionally specific bursts in cholinergic neurotransmission suggests a more specialized role in cortical processing. Here we used optogenetic methods to investigate the capacity of phasic cholinergic signaling to control behavior. Our findings indicate a causal role of phasic cholinergic signaling in using external cues to guide behavioral choice. These findings indicate the significance of phasic cholinergic activity and also illustrate the potential impact of abnormal, phasic cholinergic neurotransmission on fundamental cognitive functions that involve cue-based behavioral decisions.

Keywords: acetylcholine, cortex, attention, optogenetics

Abstract

The cortical cholinergic input system has been described as a neuromodulator system that influences broadly defined behavioral and brain states. The discovery of phasic, trial-based increases in extracellular choline (transients), resulting from the hydrolysis of newly released acetylcholine (ACh), in the cortex of animals reporting the presence of cues suggests that ACh may have a more specialized role in cognitive processes. Here we expressed channelrhodopsin or halorhodopsin in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons of mice with optic fibers directed into this region and prefrontal cortex. Cholinergic transients, evoked in accordance with photostimulation parameters determined in vivo, were generated in mice performing a task necessitating the reporting of cue and noncue events. Generating cholinergic transients in conjunction with cues enhanced cue detection rates. Moreover, generating transients in noncued trials, where cholinergic transients normally are not observed, increased the number of invalid claims for cues. Enhancing hits and generating false alarms both scaled with stimulation intensity. Suppression of endogenous cholinergic activity during cued trials reduced hit rates. Cholinergic transients may be essential for synchronizing cortical neuronal output driven by salient cues and executing cue-guided responses.

Virtually all cortical regions and layers receive inputs from cholinergic neurons originating in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, the substantia innominata, and the diagonal band of the basal forebrain (BF). Reflecting the seemingly diffuse organization of this projection system, functional conceptualizations traditionally have described acetylcholine (ACh) as a neuromodulator that influences broadly defined behavioral and cognitive processes such as wakefulness, arousal, and gating of input processing (1, 2). However, anatomical studies have revealed a topographic organization of BF cholinergic cell bodies with highly segregated cortical projection patterns (3–7). Such an anatomical organization favors hypotheses describing the cholinergic mediation of discrete cognitive-behavioral processes. Studies assessing the behavioral effects of cholinergic lesions, recording from or stimulating BF neurons in behaving animals have supported such hypotheses, proposing that cholinergic activity enhances sensory coding and mediates the ability of reward-predicting stimuli to control behavior (8–17).

In separate experiments using two different tasks, we reported the presence of phasic cholinergic release events (transients) in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of rodents trained to report the presence of cues (18, 19). These studies used choline-sensitive microelectrodes to measure changes in extracellular choline concentrations that reflect the hydrolysis of newly released ACh by endogenous acetylcholinesterase (SI Results and Discussion). Importantly, such cholinergic transients were not observed in trials in which cues were missed and in which the absence of a cue was correctly reported and rewarded. Cholinergic transients have thus been hypothesized to mediate the detection of cues, specifically defined as the cognitive process that generates a behavioral response by which subjects report the presence of a cue (20).

Here we used optogenetic methods to test the causal role of cortical cholinergic transients in cue detection (as defined above). We used a task that consisted of cued and noncued trials and rewarded correct responses for both trial types (hits and correct rejections). Incorrect responses (misses and false alarms, respectively) were not rewarded. We hypothesized that hit rates would be enhanced by generating transients in conjunction with cues, and that hit rates will be reduced by silencing cue-associated endogenous cholinergic signaling. We further reasoned that if cholinergic transients are a mediator of the cue detection response, generating such transients on noncued trials could force invalid detections (false alarms).

Phasic cholinergic activity was generated or silenced, in separate sessions, by photoactivation directed toward the cholinergic cell bodies of the BF or the cholinergic terminals locally in the right mPFC. The decision to target right mPFC was based on findings indicating that performance of the task used here enhances cholinergic function in the right, but not left, mPFC in mice (21) and activates right prefrontal regions in humans (19, 22). The present results support the hypothesis that the ability of cues to guide behavior is mediated by phasic cholinergic signaling. Particularly strong support for this hypothesis was obtained by the demonstration that, in the absence of cues, and thus of endogenous transients, photostimulation of either cholinergic soma in the BF or cholinergic terminals in the mPFC increased the number of invalid reports of cues (or false alarms).

SI Results and Discussion

Transfection Spaces and Optic Fiber Placements.

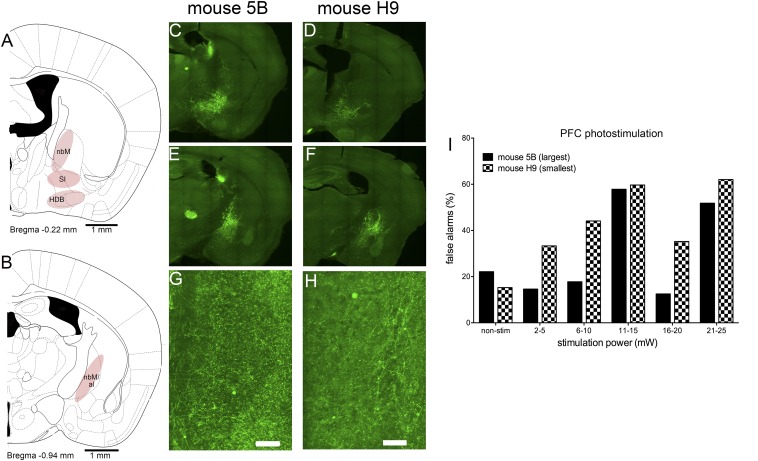

To determine the optimal volume of infusions of the EYFP-expressing viral constructs, we infused 500–2,000 nL and determined the transfection space in the BF. Infusion volumes of 1,200 nL reliably resulted in comprehensive expression of EFYP by cholinergic neurons of the three main cholinergic cell groups (Fig. S1 A and B), and thus this volume was infused into the BF of all mice (Figs. S1 and S3). Generally, the spread of EYFP expression in the BF exhibited relatively little variation across animals and groups. Fig. S1 illustrates the largest and smallest of such spaces in mice infused with the ChR2-encoding virus. Furthermore, variations in BF transfection spaces did not appreciably affect medial prefrontal EYFP expression (Fig. S1 G and H), owing to overlapping projections of the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM), substantia innominata (SI), and horizontal nucleus of the diagonal band (HDB) to this region (4).

Fig. S1.

(A and B) Schematic illustration of the main groups of cortically projecting cholinergic cell groups (pink regions) in the anterior (A) and posterior (B) basal forebrain (al, ansa lenticularis; HDB, horizontal nucleus of the diagonal band; nbm, nucleus basalis of Meynert; SI, substantia innominata) (7). Largest (C, E, and G) and smallest (D, F, and H) extension of EYFP expression in the BF of ChAT-Cre mice infused with ChR2(H134R)-EYFP in the anterior (C and D) and posterior (E and F) BF and in cingulate cortex (G and H). (Scale bar, 10 µM.) The spots of signal in thalamic regions in C and E are artifacts that fluoresced at a wide range of excitation wavelengths and were not associated with neurons or neuron terminals. Compared with EYFP labeling in the BF of mouse 5B, the BF of mouse H9 showed relatively lower levels of EYFP label in the dorsal part of the anterior nBM and the posterior end of the nbM. However, expression levels of EYFP in cortical projection fields did not differ between these two mice, owing to overlapping projections from BF regions to medial prefrontal regions (4, 6). I shows the individual false alarm rates resulting from ChR2 stimulation in noncued trials in these two mice. Although mouse H9, the mouse with the relatively smallest extent of BF EYFP expression, generated relatively more false alarms at lower stimulation power, both mice performed ∼60% false alarms at higher stimulation power. The relatively high volume of viral construct infusions (Materials and Methods) ensured that BF EYFP expression among mice infused with the three constructs reliably included the main cholinergic cell groups.

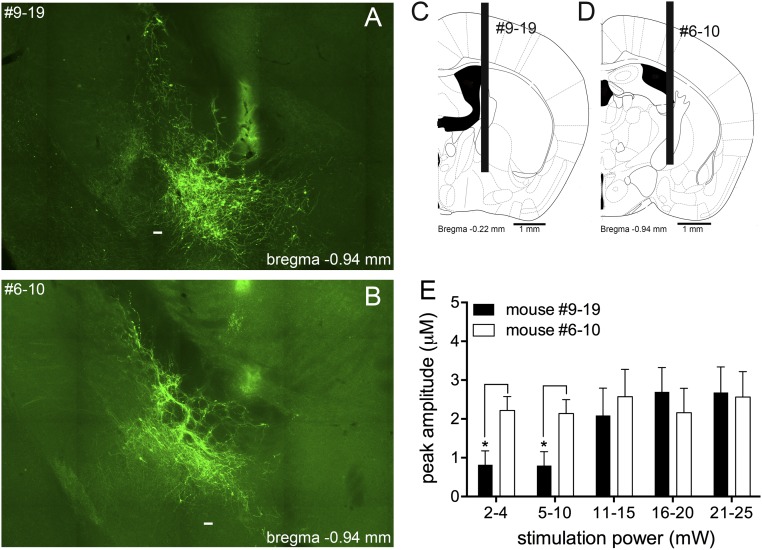

Fig. S3.

Largest (A) and smallest (B) extension of EYFP expression in the BF of ChAT-Cre mice infused with ChR2(H134R)-EYFP used in the anesthetized recording experiments. EYFP expression in mice 6–10 involved the posterior nbM and dorsal SI (B), whereas labeling in the BF of mice 9–19 extended into the anterior nbM, SI, and HDB (A). (Scale bar in A and B, 100 μm.) Optic fiber placements are shown in C and D. ANOVA (SI Results and Discussion) and post hoc comparisons indicated that choline amplitudes (E) at the two lower stimulation intensities were higher in the mouse with the smaller BF transfection space, whereas higher stimulation intensities yielded statistically similar choline amplitudes across both animals (variances based on the analyses of 10 traces per power level and mouse).

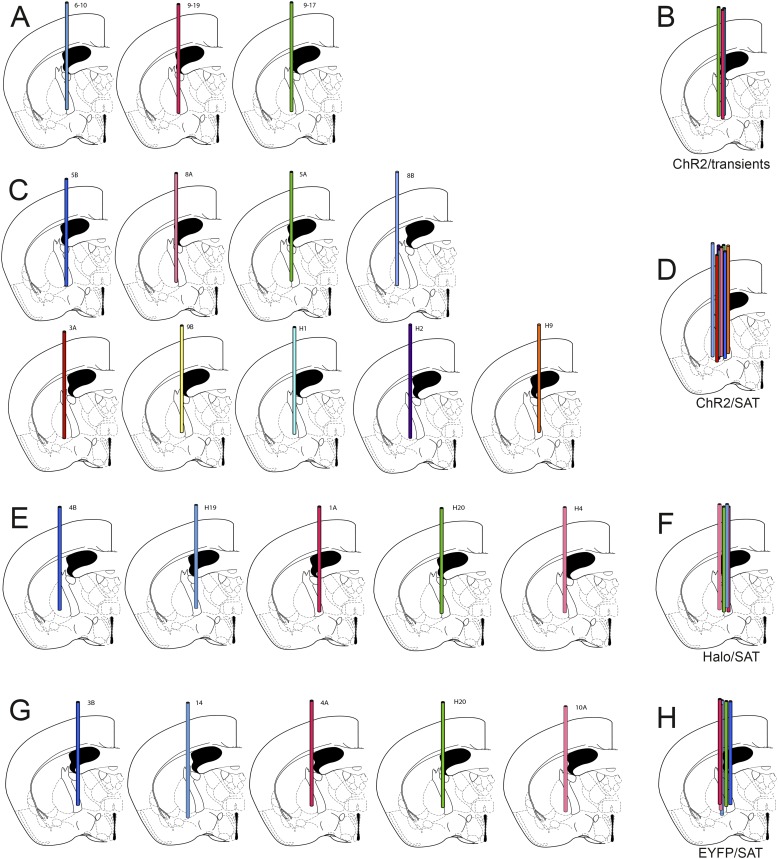

Placements of optic fibers for all groups of mice targeted the border zone between the nbM and SI (Fig. S2; see Fig. S1A for location of these cell groups). Across the four main groups of mice (ChR2/transients, ChR2, Halo, EYFP), the tips of the optic fibers were placed within a space of 0.29 mm3 (Fig. S2 B, D, F, and H).

Fig. S2.

Optic fiber placements for all animals used in this study. Fiber placements in mice used to demonstrate ChR2-evoked choline currents (A), ChR2 stimulation-evoked increases in hits and false alarms (C), Halo stimulation-induced decreases in hits (E), and effects of laser stimulation in mice expressing EYFP only (G). Placements for each group are summarized in B, D, F, and H. Optic fiber tips were placed at the transition between nbM and SI, and tips were confined within the following coordinates: AP, −0.34 to −0.82 mm; L, 1.5–2.15; V (from dura), 4.2–5.2 mm.

Estimations of the efficacy of the spread of medium to high levels of power of light from a 200-µm optic fiber (56) implies that photostimulation reliably affected cortically projecting cholinergic cell groups of the mouse BF (57). Furthermore, because EYFP labeling of varicosities and fibers in cingulate and prelimbic regions did not differ appreciably between mice and constructs (Fig. S1), as well as our observation of increases in false alarms in response to PFC stimulation in the same mice where such stimulation did not affect hit rates, variations in cortical transfection spaces are unlikely to explain these contrasting findings. Consistent with this view, false alarms evoked by ChR2 PFC stimulation of noncued trials in the two mice with the relatively largest and smallest BF transfection space did not reflect differences in viral transfection space on performance (Fig. S1I).

Experiments in mice expressing EYFP alone were designed to assess the role of potentially nonspecific effects of photostimulation (e.g., thermal effects), as well as nonstimulation effects associated with viral transfection and the impact of surgeries. Although the demonstration of potential photostimulation effects due to laser-associated energy transfer does not depend on the presence of EYFP in cholinergic neurons, our results did not indicate behavioral effects of such stimulation artifact in EYFP-expressing control mice.

Based on the considerations above, transfection space-dependent, variations in ChR2-evoked choline currents were not expected to differ across animals. To test this point, we selected two mice, corresponding to the mouse with the largest and the mouse with the smallest BF transfection space, and compared stimulation power-dependent peak amplitudes of evoked choline currents (Fig. S3). Optic fibers were placed in the anterior-medial SI and the ventral-posterior nbM, respectively (Fig. S3 C and D). The amplitudes of choline currents from these two mice (10 traces per stimulation power) did not differ [F(1,18) = 0.64, P = 0.43], but a main effect of stimulation power [F(4,72) = 4.46, P = 0.006] and a significant interaction [F(4,72) = 2.78, P = 0.04] reflected that amplitudes at the two lowest power levels were actually greater in the mouse with the smaller transfection space (Fig. S3E). At stimulation power of >10 mW, choline current amplitudes did not differ between these two mice.

Cortically Evoked Choline Currents.

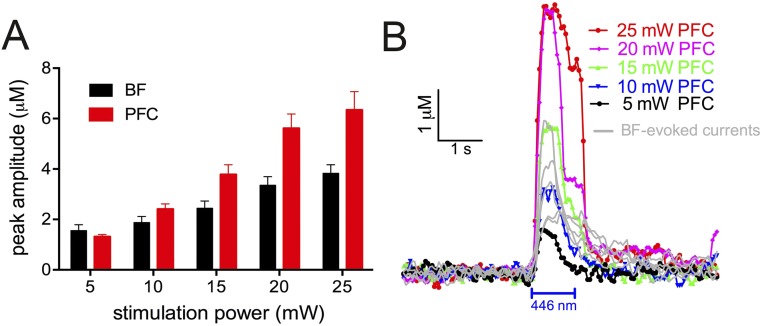

Photostimulation of cholinergic terminals in the mPFC reproduced the increases in false alarms that resulted from BF photostimulation (Results). Choline currents evoked by BF stimulation are described in Fig. 2 and further discussed below. To determine choline currents evoked by stimulation of mPFC cholinergic terminals, optic fiber tips were placed between the two pairs of platinum recordings sites (∼0.5 mm away) in the mPFC. Currents recorded via platinum sites that were not choline sensitive were subtracted from currents recorded via choline-sensitive sites (Fig. S4). As expected, photostimulation generated substantial photoelectric interference at higher stimulation levels. At lower levels of stimulation intensity (5–10 mW), cortically evoked currents reached amplitudes that were comparable with those evoked by BF stimulation. However, at higher intensities, the amplitudes of cortically evoked currents exceeded those evoked by BF stimulation [main effect of stimulation location: F(1,29) = 16.82, P < 0.001; main effect of stimulation power: F(4,116) = 38.60, P < 0.001; location × power: F(4,116) = 5.85, P = 0.002]. This effect was most likely attributable to asymmetric photoelectrical currents recorded via the lower vs. higher pairs of recordings sites, which may have resulted in an incomplete correction of choline currents by subtraction of currents from control electrodes. However, and importantly, the amplitudes of cortically evoked currents were at least as large as those evoked by BF stimulation, consistent with the finding that ChR2 stimulation of both sites during noncued trials produced comparable increases in false alarms (Fig. 5).

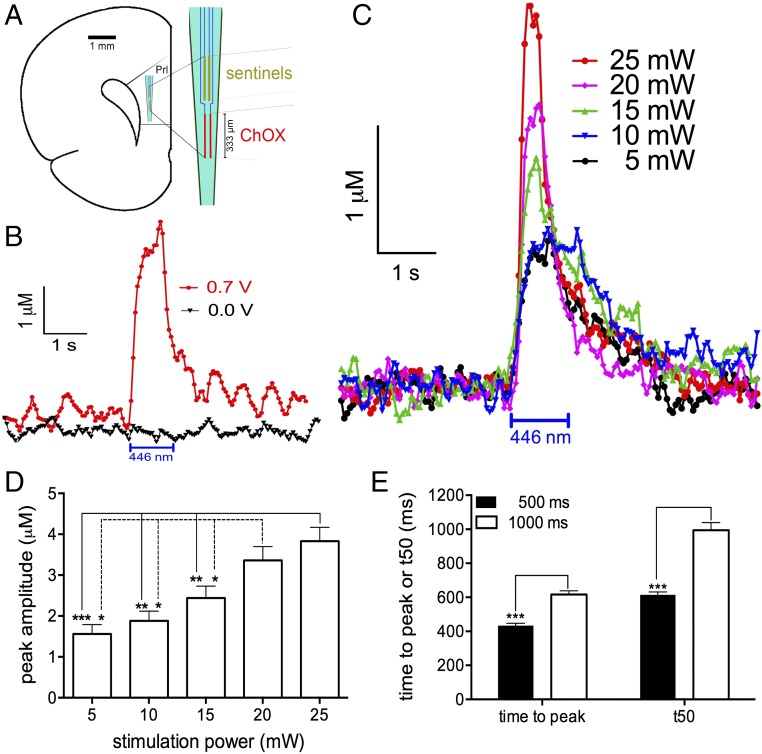

Fig. 2.

Prefrontal choline currents, recorded using choline-sensitive microelectrodes, as a function of laser stimulation power and duration. (A) Electrode configuration and placement in the prelimbic (Prl) cortex. Choline oxidase (ChOX) was immobilized on two of four ceramic-based platinum recording sites. (B) Changing the applied potential of 0.7 V, the optimum oxidation potential of the reporter molecule H2O2 (red: vs. the reference electrode) to 0.00 V (black), eliminated optogenetically evoked currents, confirming the cholinergic basis of currents and controlling for potential confounds resulting from laser stimulation. (C) Mean choline currents from all trials evoked by stimulation of ChR2-expressing cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain (BF; 5–25 mW; 1,000 ms). (D) Increasing stimulation power resulted in higher transient amplitudes (post hoc multiple comparisons: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Amplitudes did not vary by stimulation duration, and the two factors did not interact. (E) Compared with the shorter stimulation period, 1,000-ms stimulation generated transients peaked later and required more time to return within 50% of baseline (see also Fig. S5; for cortically evoked currents, see Fig. S4; for the impact of cortical state on choline currents, see Fig. S6).

Fig. S4.

Choline currents evoked by photostimulation in prefrontal cortex. The tip of the optic fiber was placed in between the upper and lower pairs of the platinum recording sites and 0.5 mm away from the electrode. Photostimulation (5–25 mW; 1,000 ms) produced sizable currents that were subtracted from the currents recorded via choline-sensitive recording sites. (A) Peak amplitudes of choline currents evoked by BF photostimulation and photostimulation in prefrontal cortex (BF data are reproduced from Fig. 2D; see also Fig. S5). Lower stimulation intensities generated current amplitudes that did not differ between the two locations. At higher stimulation levels, cortically evoked currents appeared to reach greater amplitudes, but this result likely was confounded by unequal photoelectric effects on the lower vs. higher pairs of recording sites. (B) Choline traces evoked by PFC photostimulation (mean values from all subjects), with BF-evoked currents (from Fig. 2C) shown in gray.

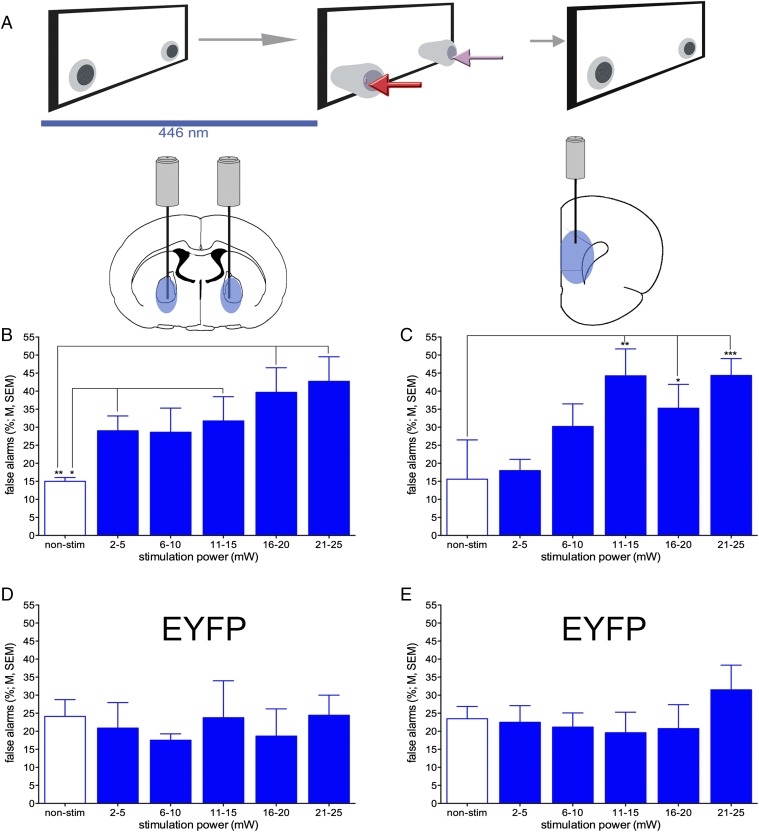

Fig. 5.

Effects of optogenetic activation of cholinergic neurons on noncued trials (n = 9 ChR2 mice). (A) On noncued trials, laser stimulation began 1,000 ms before, and ended coincident with, extension of the nose-poke devices into the operant chamber. Increasing levels of stimulation power systematically enhanced false alarms when applied bilaterally to the BF (B) or unilaterally just to the right mPFC (C; post hoc comparisons: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P,0.001). In control animals expressing EYFP, neither BF (D; n = 3) nor mPFC stimulation (E; n = 5) significantly affected the false alarm rates.

Optogenetic Stimulation Parameters.

In the present experiments, we optogenetically stimulated cholinergic neurons to test the hypothesis that cortical ACh mediates cue detection performance. This hypothesis was derived from prior recordings of presynaptic ACh release in rats performing an appetitive cue detection task (18) and, subsequently, an SAT (19). The electrochemical method used in these studies records choline concentrations by oxidizing choline via choline oxidase immobilized onto the surface of the electrode. Following ACh release events, increases in choline currents (transients) reflect transient increases in local choline levels due to the hydrolysis of newly released ACh (47). We previously demonstrated that the additional immobilization of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) onto the electrode surface does not change estimates of cholinergic activity generated in response to depolarizing cholinergic synapses, indicating that endogenous AChE concentrations are not imitating the hydrolysis of ACh (48). Although this method has allowed monitoring of cholinergic activity at a relatively high temporal resolution and revealed the presence of cholinergic transients, the measurement scheme limits the interpretation of transients in terms of the true temporal dynamics of ACh release. Specifically, peak amplitudes and the timing of the peak of choline currents may underestimate the true magnitude of the ACh release event because of competitive choline clearance by the neuronal choline transporter.

Because of the weight and size of the headstage used for amperometric recordings, it is presently not possible to record cholinergic transients in task-performing mice. Similar to electrochemical recordings of optogenetically evoked dopamine release in urethane-anesthetized animals (58), we evoked choline transients in anesthetized mice. The goal of these experiments was to determine the stimulation parameters necessary to produce transients in mice comparable to those recorded previously in performing animals. As it is likely that endogenous transients differ from those evoked in anesthetized or awake but nonperforming mice, this approach suffers from obvious limitations that eventually will only be resolved by recordings of ACh release in animals performing tasks while undergoing optogenetic manipulations. The usefulness of optogenetic stimulation parameters also needs to be judged based on the specificity and validity of behavioral effects and their theoretical context (Results).

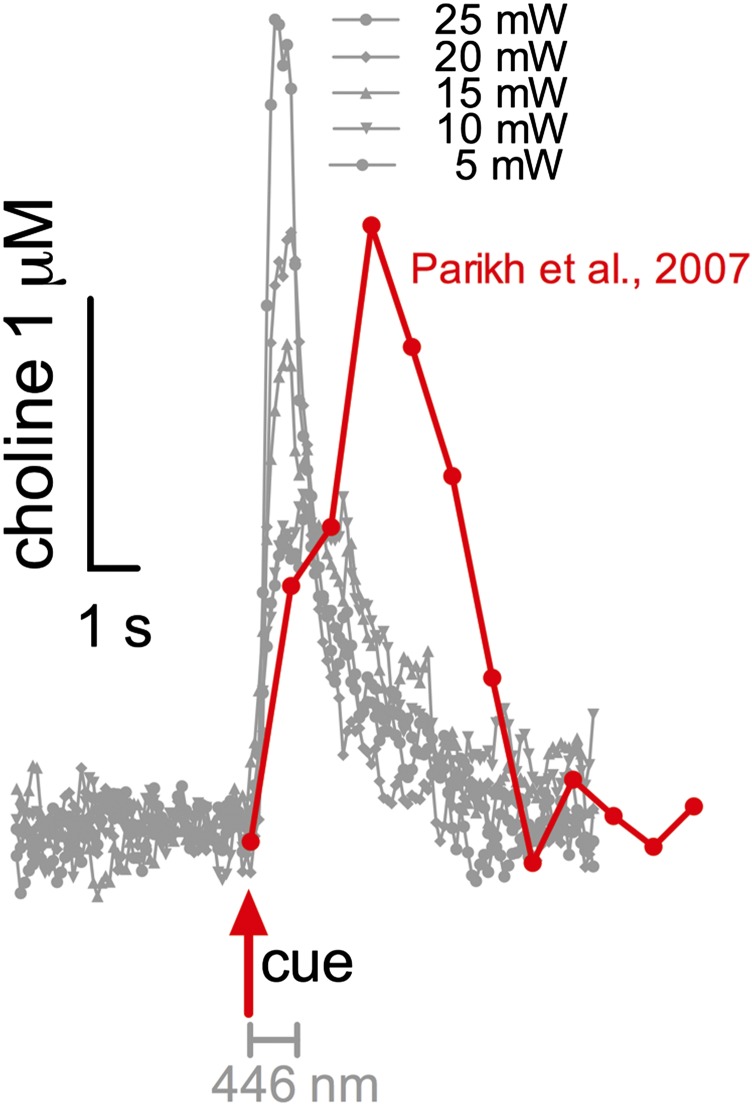

For guidance, we used the cholinergic transients recorded in behaving rats and described in Parikh et al. (18). This task is largely devoid of sources of electrostatic energy and the long intertrial intervals afforded a return of recorded currents, between trials, to pretask baseline. Thus, the currents measured in Parikh et al. provide a more realistic indication of the absolute change of extracellular choline concentration in response to a predictive cue and thus may be more similar to optogenetically evoked currents. Fig. S5 shows a cholinergic transient that was recorded during a trial in which the cue was detected [taken from figure 3A in Parikh et al. (18)]. In Parikh et al., cholinergic transients generally peaked at around 1.5–2.0 µM choline above baseline in trials in which the cue was detected, as opposed to <0.5-µM peaks recorded during trials with cues missed. As shown in Fig. S5, optogenetically evoked release at 5–15 mW peaked at 1.5–2.4 µM choline. Furthermore, the amplitude of transients evoked by the longer stimulation period exhibited slower rise times and almost twofold slower decay rates than transients evoked by the shorter duration (Fig. 2E). Although rise times and decay rates are difficult to compare between the two preparations, endogenous, cue-evoked cholinergic transients were relatively slower to rise and decay. Because evoked transients were most similar to those observed in vivo, behavioral experiments were conducted using 1,000 ms, and the effects of stimulation power (five levels, 5–25 mW) were systematically tested.

Fig. S5.

Optogenetically evoked choline currents (taken from Fig. 2C; in gray) and prefrontal choline current recorded in rats performing a cued appetitive response task (taken from figure 3A in ref. 18). Cue onset (red) and the onset and duration of photostimulation are indicated. Note that the previous data in Parikh et al. (18) were recorded at 2 Hz, whereas in the present study, currents were sampled at 20 Hz.

Optogenetically evoked choline currents in anesthetized mice mirrored the amplitudes of currents recorded in rats performing an appetitive cue detection task (18) but their rise time and decay were faster than endogenous transients. Fast rise and decay times may reflect the effects of anesthesia and/or of stimulating just one neuronal phenotype in isolation. Thus, evoked transients or the measurement of other markers of neuronal activity to determine the efficacy of optogenetic stimulation in anesthetized mice (58), serve as an approximation for selecting stimulation parameters for behavioral studies. Most importantly, our present results indicate highly selective effects of these stimulation parameters on measures of performance and that these effects interacted systematically with stimulation power.

Evoked Choline Currents as a Function of Cortical State.

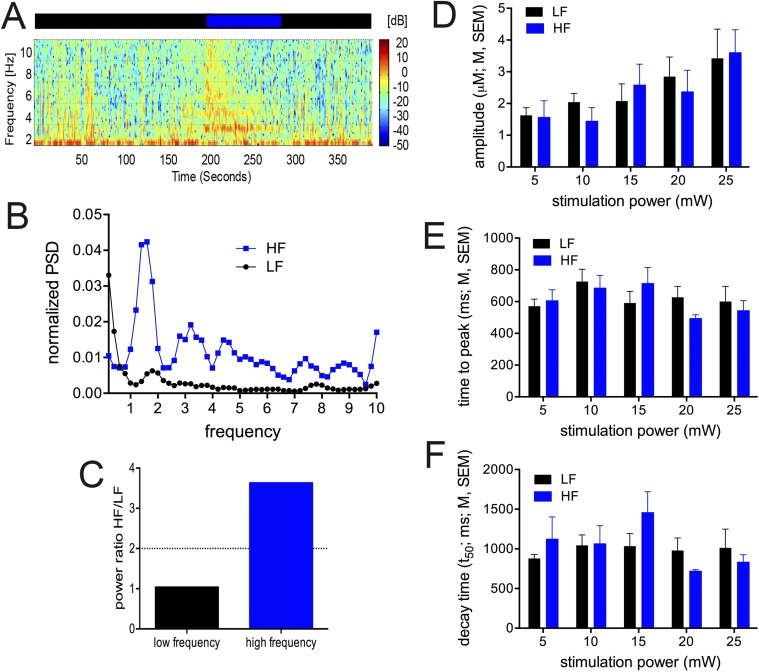

As discussed above, technical limitations required that optogenetically evoked choline currents were measured in anesthetized mice. To generate an estimate about the potential impact of anesthesia on the generation of choline currents, we tested whether evoked release varied between periods in which neuronal activity at laser onset was in a synchronized or desynchronized state (see SI Materials and Methods for definition).

Under urethane anesthesia, cortical networks spontaneously fluctuate between synchronized and desynchronized states that closely mimic natural conditions of sleep: corresponding to slow wave sleep (SWS) or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep periods, respectively (59). Highly synchronized periods show high amplitude slow oscillations at ∼1 Hz and resemble SWS. These periods are often referred to as inactive states. During wakefulness or REM sleep, this slow synchronized activity is replaced by an increase in high frequency power above 1 Hz and enhanced neocortical desynchrony representing a more awake or REM-like state (60, 61), where cholinergic neurons show a higher level of discharge (62). These transitions occur spontaneously under urethane (59) or can be actively evoked induced through somatic input such as a tail-pinch (60). Transitions between active and inactive states can also be strongly influenced by cholinergic manipulations (59), suggesting cholinergic influences are important mediators of the active state condition. Because active states are more reminiscent of the wakeful condition, we tested whether optogenetically evoked release during this period resulted in transients with different amplitudes than those observed during inactive states.

Results from these analyses are illustrated in Fig. S6. Although high- and low-frequency states were readily determined in our recordings, amplitudes, rise time, and decay rates of evoked choline currents (BF-evoked; 5–25 mW; 1,000 ms) did not differ between the two states [linear mixed models; amplitudes: main effect of state: F(1,139.75) = 0.001, P = 0.98; stimulation power: F(4,100.50) = 6.06, P < 0.001; state × power: F(4,109.84) = 0.35, P = 0.85; rise time: state: F(1,139.06) = 0.05, P = 0.82; power: F(4,138.08) = 1.973, P = 0.10; state × power: F(4, 138.25) = 0.97, P = 0.43; decay rate (t50): state: F(1,138.81) = 1.52, P = 0.22; power: F(4, 138.06) = 2.23, P = 0.07; state × power: F(4, 138.19) = 1.91, P = 0.11; Fig. S6 D–F].

Fig. S6.

Identification of low- vs. high-frequency cortical states and associated choline currents evoked by BF ChR2 stimulation (5–25 mW; 1,000 ms). Local field potentials were recorded via the same platinum recording sites used for the detection of choline currents and states were identified as described in SI Materials and Methods. (A) Example LFP spectrogram showing a spontaneous cortical state transition from a sentinel channel in a urethane-anesthetized mouse used in this study. Periods with sparse power above 2 Hz (inactive) are denoted by the black bar above the spectrogram, whereas periods of relative high frequency power above 2 Hz (active) are denoted by the blue bar. (B) Normalized PSD from the two states shown in A and coded by color. Power was normalized to total power within the time windows shown. (C) Histogram of the power ratio from the periods denoted in A and B. Power ratio compares the relative contribution of power above and power below 2 Hz (SI Materials and Methods). The dashed line denotes the cutoff used to define active and inactive states and served as the basis for all subsequent analysis. Peak amplitudes (D), time to peak (E), and decay time (time for the current to decrease by 50% from peak amplitude; F) did not differ between choline currents evoked in association with low- vs. high-frequency states.

Choline currents evoked in association with high- vs. low-frequency states (or active vs. inactive states) did not differ significantly. Thus, the results from this analysis may not directly contribute to the discussion about the potential impact of anesthesia to the optogenetic generation of choline currents. However, the spectral features of LFP-derived high-frequency states in urethane-anesthetized rats correspond with those observed in awake behaving rats (54) and optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic neurons in urethane-anesthetized mice generates cortical LFP desynchronization that mimics the desynchrony noted in awake rodents (63, 64). Thus, the present findings suggest that were we able to record optogenetically evoked choline currents in awake mice, the dynamic properties of such currents would also support the usefulness of the stimulation parameters used in our behavioral studies.

Effects of Photostimulation on Reaction Times.

As described in Materials and Methods, the two nose-poke devices were simultaneously extended into the chamber, coinciding with the termination of the cue or, in noncued trials, following the variable intertrial interval that began with the time of the prior response (or, if the prior trial was omitted, with the withdrawal of the nose pokers after 4 s). Response times were defined as the time from extending (and activating) the ports to the execution of the nose poke. Mice typically remained positioned in front of the water port during the intertrial interval and moved toward one of the ports on extension of the ports. Similar to the analyses of the effects of photostimulation on response accuracy (Figs. 4 and 5), response times were analyzed as a function of stimulation power and, with respect to hits, of cue duration Figs. S7–S9).

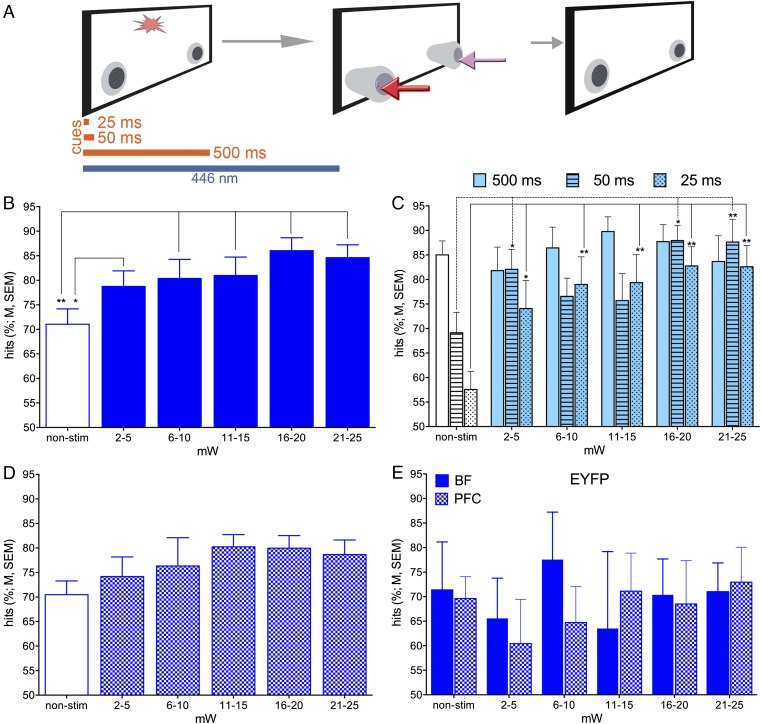

Fig. 4.

Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic neurons during cued trials (n = 9 ChR2 mice). (A) The onset of the blue light coincided with cue onset and light was terminated 1,000 ms later. (B) Hit rates, averaged over cue durations, increased in response to BF stimulation of ChR2-expressing cholinergic neurons. (C) The effects of power significantly interacted with cue duration, reflecting significant increases in hits to shortest and medium-duration cues. Post hoc one-way ANOVAs indicated that by increasing power, and thus the amplitude of evoked release, stimulation resulted in increases in hits to shortest and medium-duration cues, but not to longest cues (post hoc comparisons: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (D) ChR2 stimulation in mPFC did not significantly affect hit rates. (E) Neither BF stimulation (n = 3) nor mPFC stimulation (n = 5) affected the hit rates in EYFP-expressing control mice.

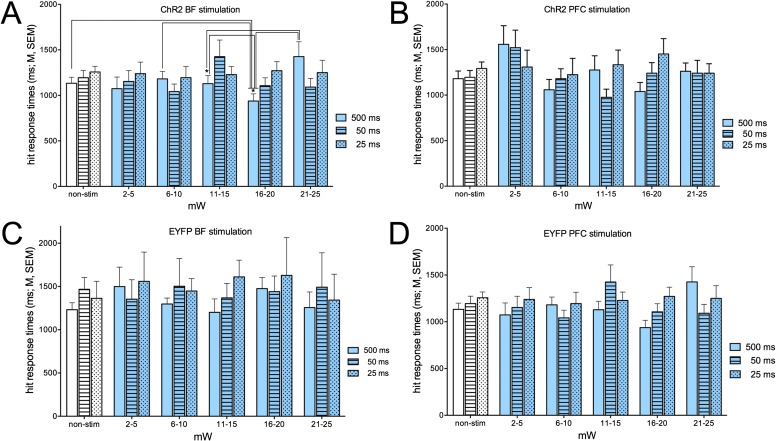

Fig. S7.

Response times for hits in trials with ChR2 stimulation of the BF (A) or PFC (B), or with photostimulation of the BF and PFC in mice expressing EYFP only (C and D). The effects of ChR2 stimulation power and cue duration on response times for hits interacted significantly (SI Results and Discussion). Post hoc ANOVAs and multiple comparisons (in A) indicated that the interaction mainly reflected that response times for hits to longest cues were relatively shortest at 16–20 mW.

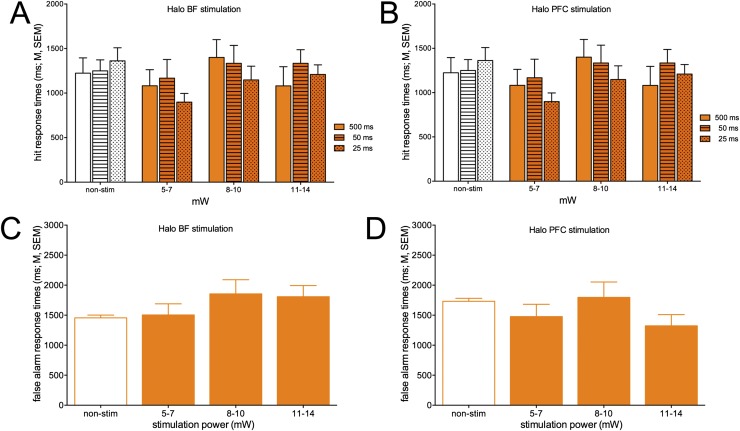

Fig. S9.

Response times for hits (A and B) and false alarms (C and D) in trials with Halo activation of the BF (Left) and PFC (Right). Response times were not significantly affected by Halo photoactivation.

In animals expressing only EYFP, there were no effects of photostimulation of the BF of PFC on the response times for hits or false alarms (hits: main effects of stimulation power, cue duration and interaction: all F < 1.64, all P > 0.33; false alarms: main effects of stimulation power, BF and PFC: both F < 1.12, both P > 0.41; Figs. S7 C and D and S8 C and D). In mice expressing ChR2, BF stimulation did not affect response times for hits [main effect of power: F(5,30) = 1.06, P = 0.39], and response times did not vary as a function of cue duration [F(2,12) = 2.96, P = 0.09]. However, the two factors interacted significantly [F(10,60) = 2.60, P = 0.011; Fig. S7A]. Post hoc one-way ANOVAs on the effects of power per cue duration indicated a significant effect for hits to the longest cues [F(5,30)= 4 .03, P = 0.031] but not for shorter cues (both F < 2.33, both P > 0.09). Multiple comparisons across hit rates to longest cues (Fig. S7A) indicated that response times at 16–20 mW were faster than in the absence of stimulation and stimulation at 6–10, 11–15, and 21–25 mW.

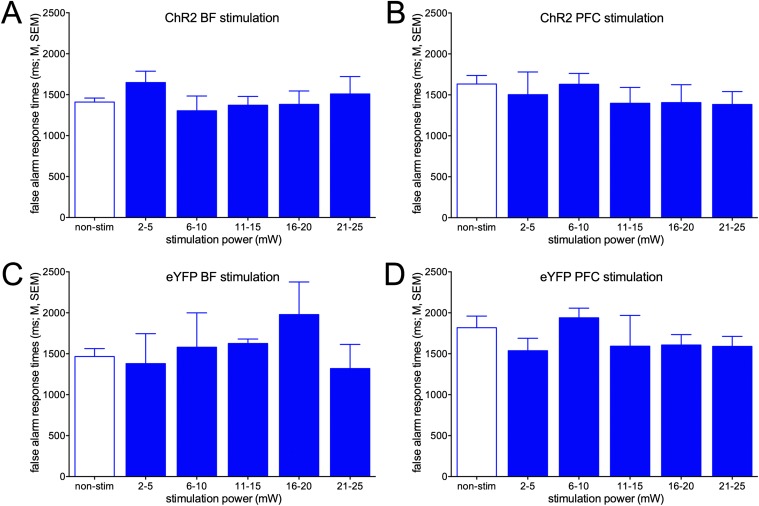

Fig. S8.

Response times for false alarms in trials with ChR2 stimulation of the BF (A) or PFC (B), or with photostimulation of the BF and PFC in mice expressing EYFP only (C and D). Response times for false alarms were not affected by photostimulation.

The response times for hits in cued trials with PFC ChR2 stimulation likewise indicated a significant interaction between stimulation power and cue duration [F(10,60) = 2.08, P = 0.048; main effects of power and cue duration: both F < 1.67, both P > 0.21]. However, one-way ANOVAs on the effects of power per cue duration failed to indicate the locus of this interaction (all P > 0.06; Fig. S7B). Inspection of the data shown in Fig. S7B suggests that similar to the effects of BF stimulation, response times to longest cues were relatively shorter when stimulated at 16–20 mW than in all other conditions.

Response times for false alarms were not affected by photostimulation of the BF or PFC [main effects of power: both F(5,30) < 0.91, both P > 0.47; Fig. S8]. Response times were generally longer for false alarms than for hits [BF: hits: 1,193.26 ± 103.36 ms; false alarms: 1,409.45 ± 49.54; ms; PFC: hits: 1,222.70 ± 70.46 ms; false alarms: 1,633.26 ± 103.26 ms; both t(12) > 2.95, both P < 0.01; comparisons based on data from the nonstimulation condition].

BF Halo activation resulted in a significant decrease in hits. Noncued trial performance and the overall number of omitted trials were not affected by Halo stimulation (Results). In trials with BF or PFC Halo activation, response time for hits (Fig. S9 A and B) or false alarms (Fig. S9 C and D) did not differ from response times in trials without photoactivation (hits: main effect of stimulation power: both F < 2.48, both P > 0.127; cue duration: both F < 0.487, both P > 0.64; interaction: both F < 0.83, both P > 0.53; false alarms: main effect of laser power: both F < 1.35, both P > 0.32).

Because BF photoinhibition increased the relative number of misses, we also analyzed response times for misses under this condition. There were no effects of stimulation power [linear mixed model: F(3,32.02) = 2.42, P = 0.08]. There was a significant effect of cue duration [F(2,32.02) = 4.35, P = 0.02], reflecting longer response times to 500-ms cues than to shorter cues, but this effect did not interact with stimulation power [F(6,32.01) = 0.01, P = 0.57; 1,597.06 ± 281.93 ms].

It was expected that photostimulation would primarily affect response times for longer cues. Such response times were relatively shorter at 16- to 20-mW stimulation than at other stimulation levels (Fig. S7A), paralleling the relatively highest overall hit rates generated at this power (Fig. 4). Although BF ChR2 stimulation during cued trials significantly enhanced hits to the two shorter cues, presumably owing to ceiling effects for hits to longest cues (Fig. 4C), the relatively fast response times for hits to longest cues at 16–20 mW may reflect that the combination of longest cues and photostimulation at this power level yielded the most effective decisional processing and preparation and execution of the hit response. This combination of salient cues and optogenetic elevation of cholinergic activity maximized the efficacy of cue detection, in Posner’s terms (20).

Although photostimulation during noncued trials, either in BF or frontal cortex, significantly increased false alarm rates (Fig. 5), response times for false alarms were not affected by ChR2 photostimulation (Fig. S8). Response times for false alarms were ∼300 ms (mean difference) longer than for hits, perhaps reflecting the relatively low confidence of animals in executing this response. The increase in false alarms seen in response to both BF and PFC ChR2 photostimulation may have been expected to be associated with relatively faster response times, indicating relatively higher certainty about the accuracy of this (false) response. Although experimentally evoked cholinergic activity forced a false response, it may also have generated conflicts between the propensity for reporting the presence of a cue and the absence of cue processing and associated synchronization of larger networks (Discussion).

All levels of BF Halo stimulation power reduced hits (Fig. 6) but did not significantly affect response times for residual hits. Because hits were significantly suppressed by BF halo activation, the trend for cue duration-dependent hit rates, observed in trials with ChR2 stimulation (Fig. S7A), was no longer seen for residual hits during Halo activation (Fig. S9A). The relative insensitivity of reaction times to optogenetic suppression may reflect that responses could only be engaged following extension of the nose poke devices, and thus response times were fixed to this event and relatively invariable.

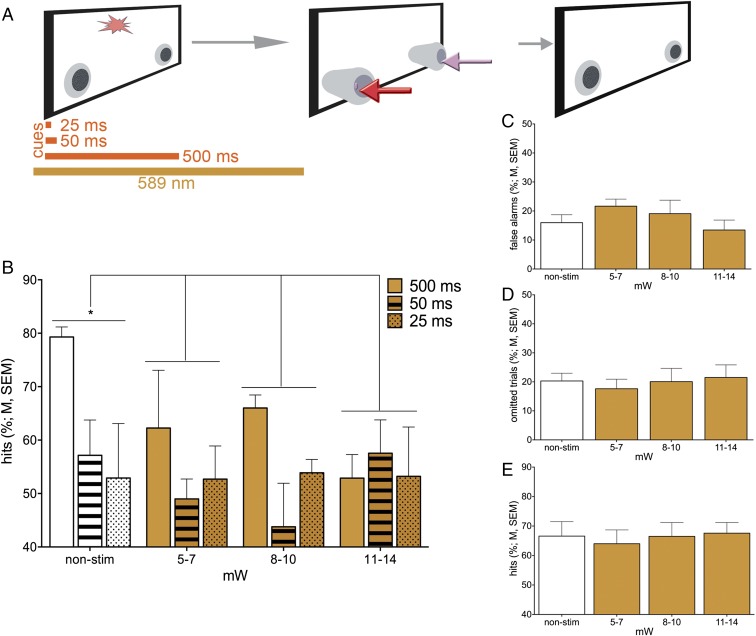

Fig. 6.

Suppression of cholinergic activity on cued trials. (A) The 589-nm laser was turned on 50 ms before the onset of the cue to fully suppress endogenous cholinergic signaling. (B) BF stimulation in Halo-expressing mice (n = 5) decreased hit rates, with increasing laser power producing greater effects. Although the effect of Halo stimulation appeared most robust for hits to longest cues, the interaction between cue duration and laser power did not reach statistical significance (post hoc comparisons of main effect of power: *P < 0.05). Halo BF stimulation neither affected the relative number of false alarms (C) nor omissions (D). Halo stimulation in the mPFC did not affect hit rates (E).

Results

Optogenetic Generation of Cholinergic Transients.

First we determined the optogenetic stimulation parameters required to generate choline currents with amplitudes that correspond with those observed in task-performing animals. Choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT)-Cre mice were virally transduced to express channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in cholinergic neurons (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1–S3). Optical fibers were implanted into the right BF and the right mPFC, concurrent with a choline-sensitive microelectrode in the ipsilateral mPFC (Fig. 2 and Table S1). Because of headstage constraints, simultaneous electrochemical recording and optogenetic stimulation were performed in anesthetized mice. Cholinergic activation was induced through somatic or mPFC terminal stimulation in a series of sweeps across multiple laser intensities (5–25 mW) and durations (500 and 1,000 ms) and recorded in mPFC (Fig. 2). Control experiments confirmed that recorded currents reflected hydrogen peroxide resulting from enzymatic oxidation of choline (Fig. 2B).

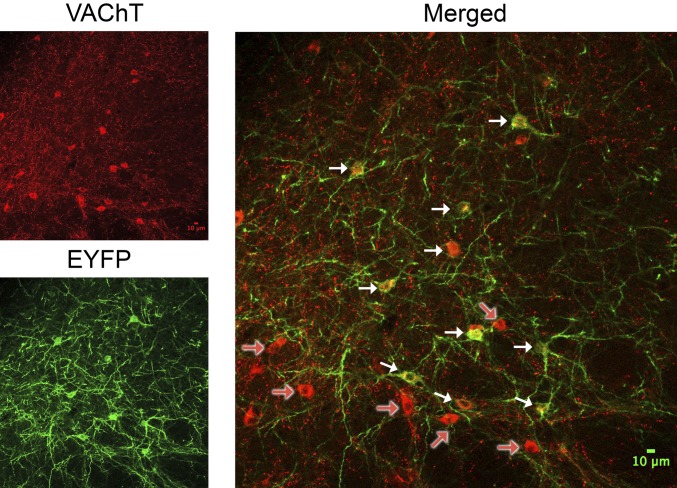

Fig. 1.

Example of transfected cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain expressing the reporter EYFP. The microphotographs show the middle slice of a confocal stack taken at the level of the ventral nucleus basalis of Meynert (coronal slice). Cholinergic neurons were visualized using an antibody against the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT; SI Materials and Methods; red; Upper Left). ChR2-H134R-EYFP–expressing neurons are in green (Lower Left). Merged microphotograph is on Right, with white arrows depicting VAChT+EYFP-immunopositive neurons and red arrows (on white contrast) depicting cholinergic neurons that were not transfected (10-μm scale inserted). Note that visualization of the colabeling of some neurons was outside this particular focal plane/slice but present in adjacent confocal slices. Neurons in the more ventral portion of this section were not transfected by the virus. The image represents the general finding that about two-thirds of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis were transfected and that EYFP expression was restricted to cholinergic neurons (Figs. S1 and S3).

Table S1.

Electrode properties based on in vitro calibration in ACSF vs. PBS

| Calibration medium | Sensitivity (pA/μM) | LOD (µM) | R2 | Selectivity |

| ACSF | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 0.26 ± 0.10 | 0.993 ± 0.004 | 192.8 ± 16.1 |

| PBS | 12.1 ± 2.5 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.994 ± 0.001 | 182.2 ± 17.3 |

Increasing BF stimulation power increased the amplitude of choline currents [F(4,116) = 34.81, P < 0.001; Fig. 2D]. Amplitudes did not vary by stimulation duration and the two factors did not interact [main effect of stimulation duration: F(1,29) = 2.90, P = 0.10, duration by power interaction: F(4,116) = 2.07, P = 0.11]. Compared with the shorter stimulation duration, 1,000-ms stimulation generated transients that peaked later [F(1,29) = 94.40, P < 0.001] and required more time to return within 50% of baseline [t50; F(1,29) = 73.32, P < 0.001; Fig. 2E]. Stimulation power did not affect peak time [main effect of power: F(4,116) = 2.00, P = 0.13] or the rate of signal decay [main effect of power: F(4,116) = 2.19, P = 0.08]. The effects of stimulation power and duration did not interact for either measure [peak time, power by duration interaction: F(4,116) = 1.05, P = 0.39; decay rate, power by duration interaction: F(4,116) = 0.24, P = 0.89; for currents evoked by photostimulation in the mPFC see Fig. S4].

The amplitudes of endogenous cholinergic transients recorded during cue-hit trials corresponded most closely with those evoked by medium laser power (Fig. S5). However, endogenous transients rose and decayed more slowly than photostimulation-evoked transients, likely reflecting that that the dynamics of behavior-associated neurotransmitter release cannot be fully reproduced by optogenetic stimulation alone. Rather, endogenous transients likely reflect the activation of large neuronal networks that involve interactions with cholinergic neurons and are modulated by factors such as cortical state or top-down input. These conditions are not fully recreated by photostimulation of a specific neuronal population (see Fig. S6 for the impact of cortical state on transient characteristics). To assess the behavioral effects of a range of amplitudes of evoked cholinergic transients, the present behavioral experiments therefore systematically evaluated the behavioral effects of a wide range of stimulation power levels (5–25 mW).

Baseline Sustained Attention Task Performance by Chattm1(cre) Mice.

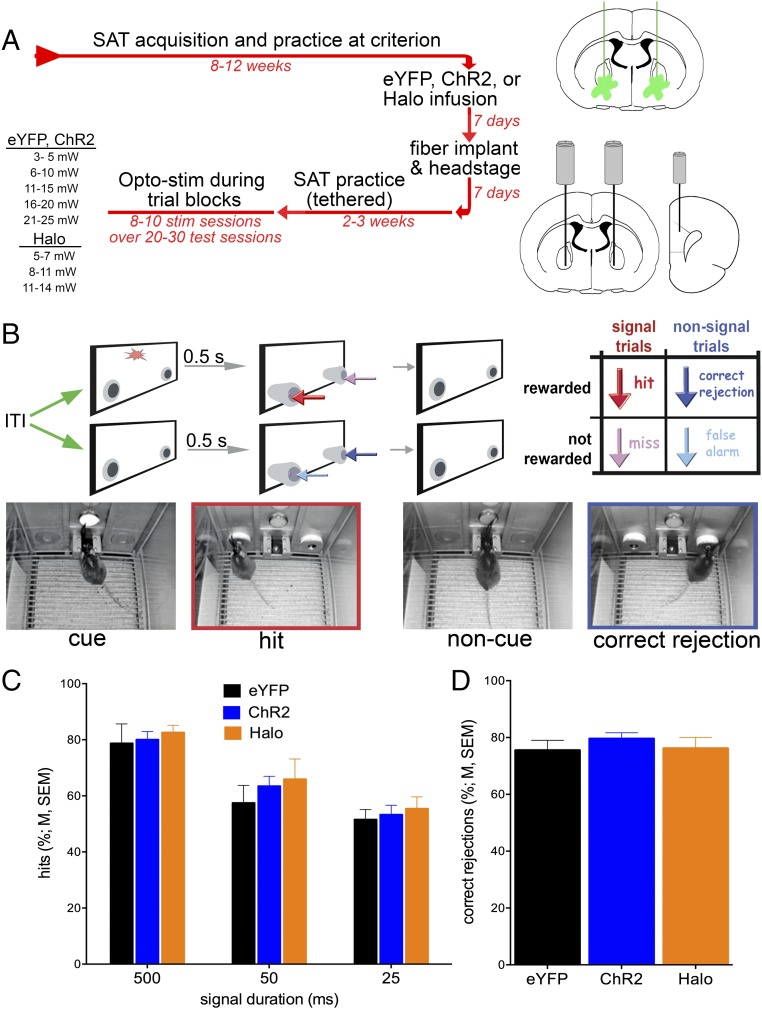

Chattm1(cre) mice were trained to criterion on the operant sustained attention task (SAT) and then received bilateral infusions of adeno-associated virus (AAV) to induce expression of either ChR2-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP), eNpHR3.0-EYFP [halorhodopsin (Halo)], or only EYFP in BF cholinergic neurons. Mice were next implanted with optic fibers bilaterally in the BF and unilaterally in right mPFC and then retrained to SAT criterion performance before tests of the effects of photoactivation on performance (Fig. 3A). As illustrated in Fig. 3B, the SAT consisted of cued and noncued (or blank) trials. Correct and rewarded responses were hits and correct rejections. Incorrect responses were misses and false alarms, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Timeline of major experimental events, task trial types, and baseline performance. (A) ChAT-Cre mice first acquired the SAT over 8–12 wk. Thereafter, they received bilateral infusions of one of the virus constructs into the BF (Upper Right). Seven days later, optic fibers were implanted into the BF and mPFC. Mice resumed task practice while tethered for 2–3 wk. The effects of optical stimulation across various stimulation intensities were tested in 8–10 sessions over the next 20–30 d with tethered nonstimulation days intermixed (Left). (B) The task consisted of a random order of cued and noncued trials. Following either event, two nose-poke devices extended into the chambers and were retracted upon a nose-poke or following 4 s. Hits and correct rejections were rewarded with water, whereas misses and false alarms were not (Right Inset; arrows in the inset and depicting nose-poke selection are color-matched; half of the mice were trained with the nose-poke direction rules reversed). Following an intertrial interval of 12 ± 3 s, the next cue or noncue event commenced. The photographic inserts show a cue presentation with a mouse orienting toward the intelligence panel while positioned at the water port (Left), a subsequent hit, a noncue event, and a subsequent correct rejection (Right). (C and D) Baseline SAT performance during tethering by groups of mice to be infused with one of the three virus constructs (n = 9 ChR2, n = 5 Halo, n = 5 EYFP). Mice detected cues in a cue duration-dependent manner (C) and they correctly rejected <75% of noncue events (D). Performance did not differ between the three groups (see Results for statistical analyses).

Baseline SAT performance, before optogenetic stimulation but after surgery, did not differ between mice previously infused with the three viral constructs [Fig. 3 C and D; main effects of group on hits and on false alarms; hits: F(2,16) = 0.30, P = 0.74; correct rejections: F(2,16) = 0.52, P > 0.61]. Hit rates were ∼80% for the longest cue durations and 50% for the shortest cues, and mice correctly rejected about 75% of the noncued trials. Hits varied with cue duration [F(2,32) = 64.593, P < 0.001], but this effect did not differ between groups [group × duration: F(4,32) = 0.287, P = 0.88]. The relative number of errors of omissions did not vary between groups [F(2,16) = 0.61, P = 0.56; mean ± SEM: 14.46 ± 7.31%].

Photostimulation During Cued Trials Enhances Hits.

Next we asked whether stimulation of BF cholinergic nuclei or mPFC terminals, coincident with cue presentation (Fig. 4A), increased the likelihood of hits. In all performance sessions, animals received trials paired with optogenetic stimulation and control trials without laser stimulation. BF ChR2 stimulation during the cue significantly increased hit rates [main effect of power; F(5,40) = 5.20, P = 0.001; Fig. 4B]. Moreover, the effects of power significantly interacted with cue duration [duration: F(2,16) = 9.71, P = 0.002; duration × power: F(10,80) = 2.26, P = 0.03]. Post hoc one-way ANOVAs indicated that increasing laser power resulted in increases in hits to shortest and medium-duration cues, but not to longest cues (Fig. 4C). Optical stimulation of mPFC cholinergic terminals alone did not significantly enhance hit rates [F(5,40) = 1.87, P = 0.14; Fig. 4D]. In contrast to the robust effects of laser stimulation in ChR2 mice, in control animals expressing EYFP alone, neither stimulation at the level of BF cholinergic neurons nor at cholinergic terminals in the mPFC (Fig. 4E) resulted in significant effects on hit rates [main effects of laser power BF: F(5,10) = 1.40, P = 0.30, mPFC: F(5,20) = 0.75, P = 0.59; for effects of photostimulation on response times for hits, see Fig. S7].

Photostimulation During Noncued Trials Enhances False Alarms.

As a strong test of the hypothesis that cholinergic transients are causal in mediating cue detection, we tested whether generating transients on noncue trials, where transients do not occur (19), can force false alarms (Fig. 5). In mice expressing ChR2, the effects of photostimulation during noncued trials were profound. In the absence of stimulation, false alarm rates remained relatively low (<20%). Stimulation of either the BF or mPFC more than doubled false alarm rates [BF: F(5,40) = 4.65; P = 0.002; mPFC: F(5,40) = 7.76, P < 0.001; Fig. 5 B and C; for response times for false alarms, see Fig. S8]. In animals expressing only EYFP, neither bilateral BF nor mPFC laser activation during noncued trials affected the relative number of false alarms [BF: F(5,10) = 0.72, P = 0.62; mPFC: F(5,20) = 1.37, P = 0.30], supporting the interpretation that manipulation of BF cholinergic signaling led to the behavioral effects, as opposed to nonspecific byproducts of intracranial light delivery (Fig. 5 D and E; for response times, see Figs. S7 and S8).

We were concerned that photostimulation during noncued trials could generate an overall response bias favoring false alarms. To test this, we compared false alarm rates from nonstimulated, noncued trials, from within the laser stimulation test session, to false alarm rates from baseline performance. Nonstimulated false alarm rates were lower than at baseline [BF: t(8) = 2.70, P = 0.03; mPFC: t(8) = 2.11, P = 0.07; baseline: 20.38 ± 2.20%; mPFC: 15.59 ± 3.28%; BF: 15.02 ± 3.16%]. These false alarm rates also paralleled levels seen in EYFP control mice from their corresponding stimulation test sessions (Fig. 5 D and E). Thus, rather than developing a riskier bias toward indicating that a cue had occurred, mice adopted a more conservative criterion during sessions with laser stimulation.

Control Analyses of Potential Carryover Effects of Photostimulation.

ChR2 stimulation in the presence and absence of cues enhanced the relative number of hits and false alarms, respectively. Several control analyses were conducted to determine whether these effects were associated with a more generalized shift in the animals’ task-performance strategy. As already detailed above, enhancing false alarm rates with optical stimulation of ChR2 did not increase the relative number of false alarms on trials without laser stimulation.

We also compared hits and omissions on nonstimulated trials to prestimulation baseline performance levels. Hit rates did not differ between baseline and nonstimulation trials during BF stimulation test days [main effect of test session, F(1,8) = 1.71, P = 0.23] or on PFC stimulation test days [F(1,8) = 1.41, P = 0.27]. There was also no interaction with the effects of test day and cue duration [BF: F(2,16) = 0.06, P = 0.92; PFC: F(2,16) = 0.57, P = 0.51]. We next analyzed animals’ performance on nonstimulated trials from each laser stimulation session, within each group (EYFP, ChR2, and Halo) using a repeated-measures ANOVA with a within-subjects factor of day. Performance on nonstimulation trials did not vary across stimulation days within any group (EYFP, ChR2, Halo; all P > 0.10). A follow-up analysis compared data from the nonstimulation condition across groups to further explore any potential differences in their baseline performance. This analysis was conducted using a one-way ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of group (EYFP, ChR2, Halo). Nonstimulation trial performance did not differ between groups for BF stimulation test days [main effect of group on hits: F(2,16) = 0.34, P = 0.72, false alarms: F(2,16) = 1.10, P = 0.36] or PFC stimulation test days [main effect of group on hits: F(2,18) = 0.26, P = 0.77, false alarms: F(2,18) = 1.69, P = 0.22].

A final control analysis used the performance data of ChR2 animals tested using the block design version of the task (SI Materials and Methods). This analysis allowed us to assess the possibility that photostimulation on a particular trial type within a block of trials biased performance on a subsequent block of trials without stimulation. Specifically, we compared hit and false alarm rates in the prestimulation block to hit and false alarm rates in the poststimulation block. Photoactivation of noncued trials, thus inducing false alarms, had no impact on hit rates in the poststimulation performance block [BF: t(1) = 0.79, P = 0.58; PFC: t(1) = 0.001, P = 0.99]. Similarly, photoactivation on cued trials, thus evoking increases in hit rates, had no impact on false alarm rates in the poststimulation performance block [BF: t(1) = −3.01, P = 0.20; PFC: t(1) = 0.20, P = 0.87]. Combined, the results from our control analyses suggest that carryover effects did not contribute to the behavioral impact of laser stimulation. Rather, the impact of transiently manipulating cholinergic activity was specific to the trial in which the manipulation occurred.

Photoinhibition During Cued Trials Reduces Hits.

In the final series of experiments, we expressed Halo in BF cholinergic neurons to test the hypothesis that silencing endogenous ACh transients coincident with cue presentation would decrease hit rates. To ensure robust attenuation, photoinhibition began 50 ms before cue onset and remained on through the entire cue period (Fig. 6A). BF activation in Halo-expressing mice decreased hit rates, with increasing laser power producing greater effects [F(3,12) = 4.94, P = 0.02; Fig. 6B; for response times, see Fig. S9]. Although the effect of Halo activation appeared most robust for hits to longest cues, the interaction between cue duration and laser power did not reach statistical significance [main effect of cue duration: F(2,8) = 6.27, P = 0.03; cue × power: F(6,24) = 1.72, P = 0.19; Fig. 6B]. The hit-reducing effect of Halo BF activation during cued trials did not influence noncued trial performance [false alarms: F(3,12) = 1.66, P = 0.25; Fig. 6C], and it did not increase the rate of omissions [F(3,12) = 0.47, P = 0.71; Fig. 6D]. mPFC activation of Halo was insufficient to affect hit rates [main effect of power: F(3,16.72) = 0.12, P = 0.95, and interaction with duration: F(6,15.79) = 0.48, P = 0.82; Fig. 6E].

SI Materials and Methods

Subjects.

A total of 32 ChAT-Cre (B6;129S6-Chattm1(cre)Lowl/J) homozygous male and female mice (3–4 mo old) were used in this study. Original breeding pairs (homozygous) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory, and all breeding was done in-house. All procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals and conducted in laboratories accredited by the AAALAC.

Viruses.

Cre-recombinase–dependent viruses encoding channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2-H134R-EYFP), halorhodopsin (eNpHR3.0-EYFP), or EYFP alone were made available from Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). Adeno-associated viral particles of serotype 5 were purchased from the Vector Core Facility at the University of North Carolina. All virus aliquots before infusion were first dialyzed 3× (1 h/wash) at 4 °C using HyClone formulation buffer 18 (Thermo Scientific). Buffer volume was 300–500 times the aliquot size across a 7,000 molecular weight cut-off membrane.

Transfection Using AAV.

An initial pilot study involving six mice was conducted to assess injection volumes and specificity of virus for the expression of the transgene. Animals received bilateral intracranial infusions of AAV (>1012 particles/mL) that produced either ChR2(H134R)-EYFP, eNpHR3.0-EYFP, or EYFP (control) expression in the basal forebrain. Each mouse received 0.5–2.0 μL/hemisphere. Infusions were performed using glass micropipettes (diameter: 1.0 mm) pulled to a sharp point and then broken at the tip to a final inner diameter of ∼20 μm. Based on preliminary results indicating that infusion volumes greater than 1.20 μL/hemisphere did not further increase the BF transfection space (see below), this volume was selected for all subsequent studies. Animals were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. Each animal received bilateral intracranial infusions of one of the three AAV constructs noted above. Injections into the basal forebrain were done slowly via pressure ejection (10–15 psi, 15- to 20-ms pulses delivered at 0.5 Hz) at the following coordinates: AP: −0.7 mm, ML: ±1.8 mm, DV (from dura): −5.0 (0.6 μL) and 4.0 mm (0.6 µL). The pipette was lowered over 3 min to DV −5.0 mm and allowed to remain in place for 3 min before infusion began. The rate of the infusion was 100 nL/min. After the first infusion concluded, following a 3-min wait, the pipette was raised to DV −4.0 and the second infusion began. At the conclusion of the second infusion, the pipette remained in place for 10 min before slowly being withdrawn over 2–3 min. Following removal, the same steps were carried out in the opposite hemisphere.

Characterization of Optically Evoked Cholinergic Transients.

Chat-Cre mice (4 mo old) were used to test the range of laser stimulation parameters (duration and intensity) necessary to evoke reliable increases in ACh release using choline-sensitive microelectrode arrays. Furthermore, we intended to generate transient increases in cholinergic activity (transients) that were similar in terms of amplitude to the transients previously found to mediate the detection of cues (18) (SI Results and Discussion). We used choline-selective biosensors and fixed-potential amperometry to measure changes in extracellular choline concentrations that reflect choline resulting from hydrolysis of newly released ACh (47). Ceramic-based microelectrodes (Quanteon) with four 15 × 333-μm platinum-recording sites were prepared for immobilization of choline oxidase (ChOX) as described earlier (47). Briefly, ChOX was immobilized on the lower pair of recording sites with a BSA-glutaraldehyde protein matrix. The upper pair of recording sites was coated with BSA alone and served as self-referencing sites that allowed for the subtraction of changes in current not due to the oxidation of choline and hydrogen peroxide. An m-phenylenediamine (mPD) barrier was fabricated onto the recording sites to prevent electroactive interferents, including dopamine, from contributing to recorded currents. Microelectrodes were calibrated using a FAST-16 electrochemical recording system (Quanteon), applying a peroxide-oxidation potential of 0.7 V (Table S1).

Animals were injected with virus encoding for ChR2-EYFP as described earlier. At 21–28 d after surgery, animals were anesthetized with urethane (1.25–1.5 μg/kg, i.p.). Thermoregulation was maintained using a water-circulating heating pad (Gaymar Model TP700; Stryker) through the duration of the surgery and subsequent recording. A craniotomy was performed which allowed for the acute placement of an optical fiber (Thorlabs) in the right basal forebrain (AP: −0.7 mm, ML: +1.8 mm, DV: −3.5 mm from dura) and a second optical fiber coupled to a microelectrode array in the right prelimbic cortex (AP: +1.8 mm, ML: +0.5 mm, DV: −2.0 mm from dura). A hole was also drilled above the cerebellum, remote to the recording area, and a miniature (100-µm-diameter) Ag/AgCl reference electrode was implanted using dental cement. Experiments began 1 h after microelectrode implantation, the time required to achieve a stable baseline current. Optical stimulation was achieved via a blue laser diode coupled to a fiber optic cable. Laser parameters, including duration and intensity, were controlled via a custom-written software package (LabVIEW) to control laser parameters including duration and intensity. Each animal received 100 stimulation trials consisting of 10 sweeps of all intensity by duration combinations (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mW, at 500- or 1,000-ms durations for each fiber position). Stimulation periods were separated by 10 s. Electrochemical currents were sampled at 20 Hz and analyzed off-line. Animals remained under urethane anesthesia throughout the duration of the experiment (2–4 h). At the conclusion of the experiment, the mouse was perfused with PBS followed by 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for histological processing. A second calibration was performed at the conclusion of the recording. Only recording sessions where sensitivity and selectivity remained above 50% of the precalibration levels were further analyzed.

In Vitro Calibration of Choline Biosensors.

All electrodes used in the electrochemistry studies were calibrated in 0.05 M PBS (pH, 6.9 ± 0.1). A separate set of electrodes was calibrated in both PBS and artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; containing the following in mM: 126.5 NaCl, 27.5 NaHCO3, 2.4 KCl, 0.5 Na2SO4, 0.5 KH2PO4, 1.2 CaCl2, 0.8 MgCl2, and 5.0 glucose) to ensure the calibration medium did not fundamentally change measures of electrode functionality. Calibrations were performed using fixed potential amperometry by applying a constant voltage of 0.7 V vs. an Ag/AgCl reference electrode in a beaker containing a stirred solution of PBS or ACSF (40 mL) maintained at 37 °C using a FAST-16mkII electrochemical system (Quanteon). Amperometric currents were digitized at 5 Hz. After achieving a stable baseline current, aliquots of stock solutions of ascorbic acid (AA) (20 mM), choline (20 mM), and dopamine (DA) (2 mM) were added to the calibration beaker such that the final concentrations were 250 µM AA; 20, 40, 60, and 80 µM choline; and 2 µM (DA). The slope (sensitivity), limit of detection (LOD), and linearity (R2) for choline, as well as selectivity ratio for AA, was calculated for individual recording sites. Calibration scores obtained in PBS did not differ from those obtained in ACSF (all four P > 0.51; Table S1).

Analysis of Electrochemical Recordings.

Raw current traces obtained from recording sessions were self-referenced by subtracting currents on noncoated sites from those on coated sites, yielding current traces that reflect choline oxidation-specific changes while removing local field potentials (LFP), stimulation, and movement artifacts. For each stimulation event, a baseline and peak concentration value was calculated. The baseline reflects the average concentration value over the 3 s before laser stimulation. The peak concentration value was the maximal value in the 2-s window following laser stimulation. All concentration values for the individual stimulation events were normalized to the proximal baseline by setting the first data point of the baseline period to 0 and expressing all subsequent values as a change from this point. Trials were then sorted by stimulation parameters and comparisons of peak amplitude and decay rate were assessed using repeated-measures ANOVA with the factors of time (pre- and poststimulation) and stimulation power. Interactions were followed up with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA and post hoc t tests.

Determination of Cortical State from Electrochemical Recordings.

Noncoated electrode sites were analyzed to extract spectral information from anesthetized recordings as described previously (54). Power spectral density (PSD) over the 3-s baseline window before optogenetic stimulation was calculated using a discrete Fourier transform of the Hann-tapered data. Each PSD was then normalized to the total power from the same time bin. High frequency (HF) was defined as normalized power >2 Hz and low frequency (LF) as normalized power <2 Hz. An HF/LF ratio was calculated for each trial to determine the basal cortical state at laser onset. Active states were defined as those with ratios greater than 2.0 and accounted for 33% of all stimulation trials. Peak amplitudes for stimulation-evoked release from active and nonactive cortical states were then compared using a linear mixed model with factors of state and power. Main effects and interactions were followed up with post hoc t tests when appropriate. All data analysis was performed using Matlab and the associated signal processing toolbox (MathWorks).

SAT Training.

The SAT was originally developed as a task for assessing sustained attention performance in rats (55) and later adopted for research in humans (50) and mice (51). A total of 19 Chattm1(cre) homozygous male and female mice (3–4 mo old at the beginning of training) were used in this part of the study. Animals underwent a total of 4–6 mo of training of the operant SAT with the oldest mouse being ∼9 mo old at study conclusion. Animals had free access to food throughout the behavioral training paradigm and were individually housed on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. Animals were trained at approximately the same time every day (between 6 and 8 h after lights-on) and, in addition to the water delivered during task performance (below), they were given an additional 10 min of free water access after each daily training session.

Animals were first gradually titrated from 24-h water access down to a single hour of water access over a period of 6 d. SAT training took place 7 d/wk and was conducted in individual operant chambers (MedAssociates) that were housed within sound-attenuating cabinets and modified to contain two retractable nose pokes (51), a centralized panel (cue) light (2.8 W), and a house light located on the opposite wall (2.8 W). Additionally, a water dispenser attached to a syringe pump was located just below the panel light and between the two retractable nose pokes. Mice were removed from their home cages and placed in unlit chambers for 5 min before task onset. Mice were first trained to nose poke for a water reward in accordance with a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement. Next they were trained to detect, discriminate, and respond to the presence and absence of signals (or cues). A training session lasted 40 min, with individual trials separated by an intertrial interval (ITI) of 12 ± 3 s. Trials consisted of signal events and nonsignal events that occurred with equal probability. On each trial, the outcome was defined by the animals’ response during the nose-port extension window (Fig. 3B). During this period, both ports extend for 4 s or until a poke occurs. Signal trials began with a 1-s illumination of the central panel light, followed by extension of both nose ports. A left poke was counted as a hit, and a right poke was counted as a miss. In the absence of the central panel light illumination (nonsignal trials), a left poke was counted as a false alarm, and a right poke was counted as a correct rejection. Each correct response produced a water reward (5.0 μL for each hit or correct rejection) and incorrect responses (miss or false alarm) were not rewarded. Half the mice were trained in a counterbalanced fashion with the port rules reversed. The house light was off during this second phase of training, and incorrect responses resulted in a repeat of the trial, up to three times (correction trials). If the mouse continued to respond incorrectly after three consecutive correction trials, a forced-choice trial was initiated: a signal or nonsignal event followed by extension of only the correct port for 90 s or until a nose poke occurred. In forced-choice signal trials, the central panel light remained illuminated for the duration of the port extension. Progression to the final training phase occurred after 3 consecutive days of correct responses of ≥69% to both signal and nonsignal trials. The third phase of SAT training signal durations were shortened to 500, 50, or 25 ms (pseudorandom order), and correction trials and forced-choice trials were eliminated. Following reaching criterion for this stage (≥70% hits to longest signals, ≥70% correct rejections, and <20 omissions per session, for three consecutive sessions), mice were advanced to the final stage of SAT training. In the last stage of training, all parameters remained the same except the house light was illuminated. Above-chance performance under this condition requires orientation toward the intelligence panel and eliminates a large proportion of task-irrelevant or competitive behaviors and required several weeks of additional practice for mice to reach final performance criterion (identical to the prior training stage). Thereafter, mice underwent surgery to inject virus into the basal forebrain.

Surgery for Virus Infusion and Optic Fiber Placement.

Once animals achieved criterion, they were randomly selected to undergo AAV infusions for one of three possible constructs (described earlier). Animals were removed from task and given free water for 3 d before surgery for virus infusion. Because of the length of surgery associated with both procedures, bilateral infusions of virus (60–90 min) and fiber placement surgery (90–120 min) procedures were separated into two surgeries. Following virus infusion, animals were allowed to recover over 7–10 d and then underwent the second surgery for fiber placement (Fig. 3A).

Surgery for Optic Fiber Placement.

Optic fibers (diameter: 200 μm; Thorlabs) were glued to 2.5-mm SS ferrules (F10064F25; Fiber Instrument Sales). Fibers were hand polished, and only fibers with >60% coupling efficiency were used. Light delivery was adjusted based on coupling efficiency to match the intensities described below. Seventeen of 19 mice (9: ChR2, 5: Halo, and 3: EYFP) received configurations of three optic fiber per ferrules located at the following coordinates: unilateral right prelimbic cortex (AP: +1.9 mm, ML: +0.5 mm, DV: −1.0 mm from dura), bilateral basal forebrain (AP: −0.7, ML: ±1.8, DV: −3.5 from dura). Two EYFP mice received single ferrules targeting prelimbic cortex only. All ferrules were secured using dental acrylic. The acrylic headstages were then painted with two coats of flat black acrylic enamel (Duplicolor 8555) and recoated with acrylic to prevent any light from exiting the headstage. Headstages were tested for opacity in total darkness before restarting training and every subsequent training session until the experiment ended.

SAT Performance During Photoactivation and Suppression.

Animals were allowed to recover for 7 d after fiber placement, with the last 3 d coinciding with a gradual restriction of water access before restarting training. Postsurgery training took place in a specially designed chamber that accommodated a 1 × 2 way optical commutator (FRJ_1 × 2i; Doric Lenses). Mice were trained while tethered until they reestablished and maintained criterion performance for 3 d. The laser stimulation portion of the experiment then began. Mice expressing EYFP or ChR2 performed SAT sessions to determine the effects of light alone (EYFP) or photoactivation of cholinergic neurons on behavior at five intensities (2–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21–25 mW). In mice expressing eNpHR3.0-EYFP, effects of photosuppression on behavior were measured across three intensities ranges (5–7, 8–10, and 11–14 mW). Light for photoactivation was delivered via a 446 nm Blue laser (P/N NDB7112E; LD Nichia) under control of a laser diode driver (LaserSource 4205; Arroyo Instruments), whereas photoinhibition was delivered via a yellow CW DPSS laser (589 nM; OEM Laser Systems) that was continuously on with light delivery controlled via an optical shutter (TS6B1ZM0; Vincent Associates/Uiblitz). Laser output was delivered through a fiber optic cable controlled via a custom written software package (LabVIEW). On stimulation trials, light was delivered for 1,000 ms coincident with cue onset for signal trials or for the 1,000 ms immediately before nose-port extension on nonsignal trials. Photo suppression was similar with the notable exception that the laser onset occurred 1,050 ms before port extension (50 ms before cue onset on signal trials). This step was taken to prevent cue-onset evoked increases in cholinergic activity. Photosuppression or photoactivation was delivered on a subset of trials within a given 40-min training window. Animals underwent testing in one of two design configurations. Block design: a small number of animals (ChR2: n = 2, EYFP: n = 2) were given laser stimulation on every signal or nonsignal trial (never both; the alternative trial type was run on a different day) over an 8-min block of trials, and this block of trials was either the 8- to 16- or the 16- to 24-min period of the training session. The remaining blocks had no laser stimulation. Equal probability design: All other animals (ChR2: n = 7, EYFP: n = 3, Halo: n = 5) underwent a modified SAT session that allowed nonsignal and signal trials to be tested during the same SAT session. For this cohort, light delivery occurred randomly on 50% of all trials irrespective of trial type (signal or nonsignal). Regardless of configuration, each laser stimulation day was followed by one or more SAT practice days while tethered but without light delivery to ensure animals had recovered performance before providing another photostimulation session. Results did not differ between the two stimulation configurations and therefore were pooled for the final analysis.

Postperformance Tissue Processing, Histology, and Imaging.

After animals had concluded training at all laser-power conditions, they were euthanized via pentobarbital overdose (Fatal-plus; Vortech Pharmaceuticals). Mice, once unresponsive, were transcardially perfused with 30 mL PBS, followed by 30 mL 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. Brains were carefully removed and postfixed for 4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde before being transferred to a 30% (wt/vol) sucrose solution. After 24 h in sucrose, brains were sectioned in 40-µm coronal slices with a freezing microtome (CM 2000R; Leica). Tissue sections were collected throughout the basal forebrain and frontal cortex. For all animals, alternate sections were stained for Nissl substance (cresyl violet acetate; Fisher Scientific). The remaining sections were stained for VAChT or ChAT. Sections designated to undergo antibody staining were rinsed three times in 0.05 M Tris⋅HCl buffer (Tris, pH = 7.6) for 10 min each, followed by a blocking buffer [5% (vol/vol) serum; Jackson ImmunoResearch, 017-000-121] and 0.2% Triton in 0.05 M Tris⋅HCl for 60 min on a tabletop rocker. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with goat anti-ChAT antibody (Millipore) diluted 1:500 or rabbit anti-VAChT antibody (Synaptic Systems) diluted 1:3,000. The following day, sections were washed in wash buffer (0.05 M Tris⋅HCl containing 0.2% triton) three times for 10 min each and then incubated with a secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594 donkey-anti-goat; Life Technologies A11058; or Cy3 goat-anti-rabbit; Jackson ImmunoResearch) 1:200 or 1:500 for 2 h at 25 °C. Sections were then rinsed three times for 5 min each in Tris⋅HCl before being mounted on gelatin-coated slides to dry for several hours in a light-free environment. Slides were then coverslipped (Vectashield; H-1400) and stored at −20 °C until imaging. Slides were imaged with a Leitz LSM 700 confocal microscope to determine whether fiber placement location was localized to areas within the target region (nBM/SI and prefrontal cortex). We also verified that the expression of the viral reporter limited to cells also expressing ChAT or VAChT (Fig. 1).

Analyses of SAT Performance and Laser Stimulation Effects.

Statistical analyses were carried out to determine differences in performance associated with cholinergic activation or cholinergic suppression relative to within session performance and across groups. SAT performance yielded measures of hits, misses, false alarms, correct rejections, and omissions. To facilitate comparison across the two testing configurations defined above, data from SAT sessions where the laser was turned on only on signal trials were collapsed with data from SAT sessions where the laser was turned on only during nonsignal trials. The trials from both days were combined to create a single “meta”-day containing data from stimulated and nonstimulated trials. Mixed analyses tested the main effects and interactions of treatment conditions, laser intensity, and cue duration (where applicable: 500, 50, and 25 ms). To allow for a within-subjects comparison of performance in the presence and absence of laser stimulation, nonstimulation performance was collapsed across days. This single “nonstimulation” condition was calculated individually for nonstimulation trials on both PFC and BF test days and was used to assess the effects of increasing laser power on performance. Comparisons were made for overall hits and FA by brain region (PFC or BF). One mouse in the Halo condition and receiving PFC stimulation did not receive all power conditions. The collective Halo mPFC stimulation data were analyzed using a linear mixed model. Covariance structures were selected based on Akaike's information criterion (52). Follow-up analyses directly comparing performance of the different groups on cue and noncue trials during the different stimulation conditions used a one-way ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of condition (EYFP, CHR2, Halo). Comparisons were made for overall hits and FA by stimulation region. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics V. 20.0). The α was set at 0.05, and exact P values were reported (53).

Discussion

Cortical cholinergic activity is critically involved in sensory perception and attention (9, 13, 23, 24). Here we demonstrate that ACh signaling is an essential mechanism mediating the utilization of environmental stimuli to guide behavior. Optogenetically generated cholinergic transients enhanced the detection of cues and, if generated during noncued trials, increased the rate of false alarms. Conversely, silencing cholinergic activity resulted in misses of long, salient cues that are normally detected (19). Generating cholinergic transients in the mPFC was sufficient to cause false alarms in the absence of a cue while enhancing or suppressing hits required bidirectional modulation of cholinergic activity in more widespread BF projection fields.

Trial-to-Trial–Based Decisions and Support for a Cholinergic Basis of Photostimulation Effects.

Evoking cholinergic activity increased the probability of reporting the presence of a cue, even in noncued trials. The task used in the present experiments included a random sequence of cued and noncued trials and both hits and correct rejections were rewarded. These factors allowed us to attribute the behavioral effects of photostimulation to individual trials and further to exclude potential carryover effects or cue reporting biases. Because correct responses on cued and noncued trials (hits, correct rejections) were rewarded equally, the effects of evoked cholinergic activity cannot be attributed to reward contingencies. A role of reward was also rejected in our previous electrochemical recording studies (18, 19). Furthermore, we found no evidence to suggest that photostimulation impacted the performance on nonstimulated trials. Combined, these findings reject an interpretation of stimulation effects in terms of generalized decision or response biases, the altering of value representations, or other processes that could generally alter the threshold for indicating the presence of a cue.

Current technical limitations did not allow recording cholinergic transients in conjunction with optogenetic stimulation in task-performing mice. Thus, the interpretation of the present behavioral effects, in terms of being mediated by cholinergic activity, is derived from evidence of the effects of cholinergic photostimulation in anesthetized mice (Fig. 2 and Figs. S3–S6) and the cholinergic transients previously recorded in animals performing cue detection tasks (18, 19). Despite these limitations, the selectivity of the behavioral effects suggests that our stimulation parameters evoked biologically relevant ACh release. Specifically, increasing laser power, and therefore the amplitude of cholinergic transients, produced larger behavioral effects. ChR2 stimulation during cued trials preferentially enhanced the hits to short- and medium-duration cues; such cues are missed at higher rates and thus are less likely to be associated with cholinergic transients. Increasing laser power resulted in higher hit rates specifically to these cues. Conversely, silencing cholinergic activity reduced hit rates to long cues, consistent with effects of cholinergic lesions (9). Taken together, these findings indicate systematic relationships between the salience of cues and photostimulation power and, by extrapolation, the amplitudes of evoked and suppressed transients.

We cannot exclude the possibility that optogenetic stimulation triggered corelease of other neurotransmitters from cholinergic terminals (25), or that mechanisms secondary to cholinergic stimulation are essential for mediating the behavioral effects described here (26). However, in addition to results from our electrochemical recordings studies (18, 19), a considerable literature on the effects of pharmacological manipulations of the cholinergic system on attentional performance in animals and humans (27–29) is consistent with the present attribution of a cholinergic mechanism underlying the effects of optogenetic stimulation on cue detection processes (as defined in the introduction).

BF vs. mPFC Stimulation Effects.