Significance

In addition to the well-characterized main nuclear latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) protein of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV), cytoplasmic LANA isoforms are known to exist, but their function has thus far been unknown. Here we show that N-terminally truncated cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA play a role in antagonizing the innate response triggered, by means of cGMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and stimulator of interferon genes (STING), during the reactivation of KSHV from latency. By directly interacting with cGAS, cytoplasmic LANA variants inhibit the cGAS-STING–dependent induction of interferon and thereby promote the reactivation of KSHV from latency. These findings extend the roles of a γ-herpesvirus latent protein into the lytic replication cycle.

Keywords: KSHV, cytoplasmic LANA, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase

Abstract

The latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) is mainly localized and functions in the nucleus of latently infected cells, playing a pivotal role in the replication and maintenance of latent viral episomal DNA. In addition, N-terminally truncated cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA, resulting from internal translation initiation, have been reported, but their function is unknown. Using coimmunoprecipitation and MS, we found the cGMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), an innate immune DNA sensor, to be a cellular interaction partner of cytoplasmic LANA isoforms. By directly binding to cGAS, LANA, and particularly, a cytoplasmic isoform, inhibit the cGAS-STING–dependent phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3 and thereby antagonize the cGAS-mediated restriction of KSHV lytic replication. We hypothesize that cytoplasmic forms of LANA, whose expression increases during lytic replication, inhibit cGAS to promote the reactivation of the KSHV from latency. This observation points to a novel function of the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA during lytic replication and extends the function of LANA from its role during latency to the lytic replication cycle.

Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV, also known as HHV-8) is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD), and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL). KSHV-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), originally identified in KSHV-infected PEL cell lines and encoded by KSHV orf73 (open reading frame 73), is constitutively expressed in all forms of KSHV-associated malignancies (1–5). LANA is essential for latent KSHV replication and maintenance of latency by tethering the viral episome to cellular chromosomes during cell division (6, 7). As a multifunctional protein, LANA is involved in many cellular processes, such as regulation of cellular and viral transcription, cell growth, angiogenesis, and immune modulation (8–15).

Innate immunity is the first line of defense against incoming pathogens. KSHV efficiently inhibits the host innate immune response by targeting several pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) signaling, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and the DNA sensor cGMP-AMP synthase (cGAS). Several KSHV-encoded proteins, such as viral IFN regulatory factor 1 (vIRF1), vIRF2, vIRF3, K8 (k-bZIP), LANA, ORF45, ORF64, ORF75, and RTA (replication and transcription activator)/ORF50 are known to modulate the innate immune response (16–21). RTA inhibits the TLR-mediated innate immune response by down-regulating the expression of TLR2 and TLR4 (19). The KSHV deubiquitinase encoded by ORF64 inhibits the RIG-I–mediated innate immune response by reducing ubiquitination of RIG-I, a crucial step in the activation of RIG-I (20). vIRF1 targets STING and ORF52 inhibits cGAS enzymatic activity to prevent the cGAS-mediated DNA sensing (21, 22). Recently, two oncogenes of DNA tumor viruses, including E7 of human papillomavirus and E1A of adenovirus, were reported to block cGAS-STING signaling pathway by binding to STING (23). LANA, one of the major proteins expressed in KSHV latently infected cells, represses IFN-β production by competing with IRF3 to bind the IFN-β promoter (15). The processed forms of LANA resulting from caspase cleavage blunt apoptosis and caspase 1–mediated inflammasome in KSHV-infected cells exposed to oxidative stress (24). LANA is also involved in the modulation of adaptive immunity by inhibiting antigen presentation of both major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) and class II (MHC II) (25–28). Meanwhile, host restriction factors inhibit KSHV infection by activating immune responses. KSHV infection of human primary naïve B cells induces rapid activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) expression, which plays a role in the innate immune defense against KSHV (29).

It is well established that LANA localizes to the nucleus of infected cells, where the known functions of LANA involve binding both the viral episome and cellular chromosomes, and recruitment of chromatin-associated proteins such as BRD2, BRD4, and MeCP2 (30–34). In addition, a recent publication reported that lower-molecular-weight LANA isoforms can be generated by the use of noncanonical internal translation initiation sites within the N-terminal domain and are localized to the cytoplasm, because they lack a nuclear localization signal (35). The generation of LANA isoforms lacking part of the N-terminal domain by caspase cleavage has also been recently reported (24). However, the functions of these cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA are still unknown.

Here we report the identification of cellular proteins interacting with KSHV LANA using coimmunoprecipitation and MS. Among these is cGAS, an innate DNA sensor, which, on recognition of dsDNA or RNA:DNA hybrids in the cytoplasm, generates 2′3′ cGMP-AMP (2′3′cGAMP) (36–41). cGAMP then binds to stimulator of IFN genes (STING, also known as TMEM173, MITA, ERIS, or MPYS), which recruits and activates TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) to induce the expression of type I IFNs, which in turn induce expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). cGAS was reported to inhibit replication of DNA viruses such as Murid herpesvirus 68 (MHV-68), vaccinia virus, and herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) (42, 43). In this study, we find that the cytoplasmic isoforms of KSHV LANA interact with cGAS and antagonize its function in type I IFN signaling, thereby promoting the reactivation of KSHV from latency.

Results

cGAS Is a Cellular Binding Partner of LANA.

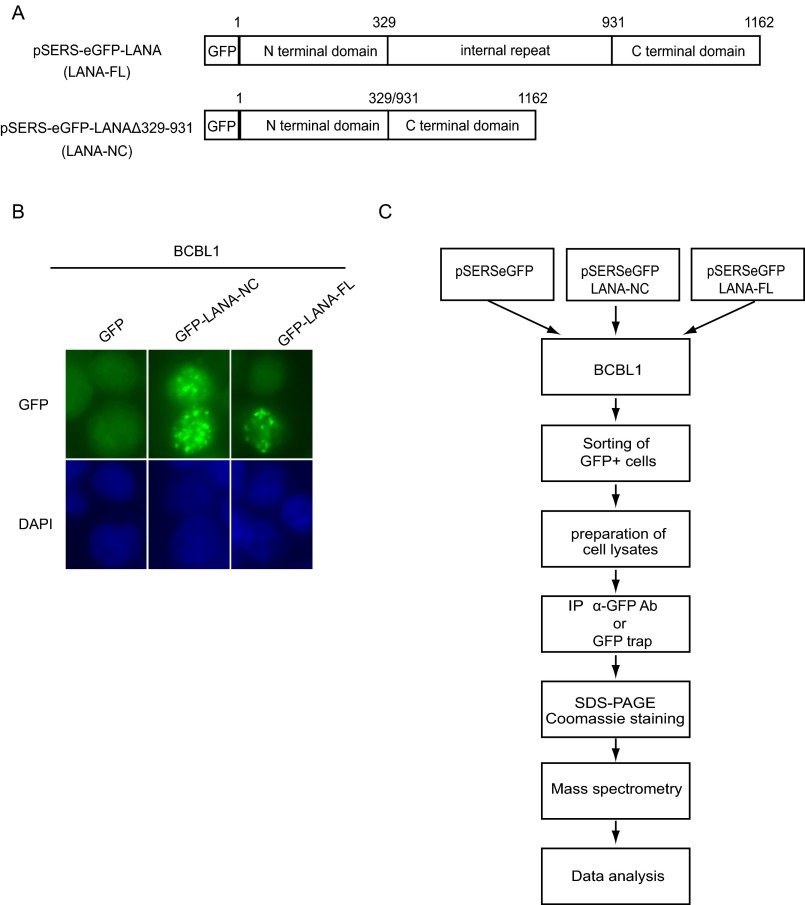

LANA, a multifunctional protein, is expressed in all KSHV-infected cells. LANA consists of an amino terminal domain, an extended internal repeat region, and a carboxy terminal domain involved in the binding to viral episomal DNA (4, 5, 25, 44–46). The internal repeat region is required for the maintenance of viral episomes (47–49). To identify novel cellular proteins interacting with the N- and C-terminal domains or the internal repeat region of LANA, we transduced the BCBL-1 PEL cell line with lentiviral vectors expressing a fusion protein of GFP with full-length LANA (LANA-FL) or a LANA mutant lacking the internal repeat region (LANA-NC, LANAΔ329–931) (Fig. S1A). Both GFP-LANA-FL and GFP-LANA-NC proteins localized to the typical LANA speckles in KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells (Fig. S1B).

Fig. S1.

Identification of cGAS as an interaction partner of LANA in BCBL-1 cells. (A) Schematic representation of LANA constructs used for coimmunoprecipitation and MS analysis of BCBL-1 cells stably expressing full-length LANA (LANA-FL), LANA Δ329–931 (LANA-NC), or GFP. (B) BCBL-1 cells transduced with GFP-LANA-FL or GFP-LANA-NC were fixed and GFP expression analyzed by microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. (C) Workflow of the coimmunoprecipitation and MS analysis.

As shown in the experimental workflow (Fig. S1C), BCBL-1 cells expressing GFP-LANA-FL or GFP-LANA-NC were lysed, and GFP-LANA proteins were immunoprecipitated with either beads conjugated with an anti-GFP antibody or GFP-trap, a small GFP-binding protein, coupled to agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by MS. Cellular partners of GFP-LANA-FL and GFP-LANA-NC identified with high frequency (at least three times in four MS runs of GFP-LANA-FL or GFP-LANA-NC after subtracting the hits from the control groups) are shown in Table S1. Several of the cellular proteins identified here have previously been reported to interact with LANA. Examples include lysine-specific demethylase 3A (KDM3A), death domain-associated protein 6 (Daxx), core histone macro-H2A.1 (H2AFY), FACT complex subunit SSRP1 (SSRP1), nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 (NUMA1), and centromere protein F (CENPF), as reviewed in ref. 9. Interestingly, we found Daxx to be the binding partner of LANA-FL, but not of LANA-NC, which is in line with a previous study which reported that the deletion of the internal repeat region of LANA abrogates Daxx binding (50). Among the newly identified LANA binding proteins was the DNA sensor cGAS, which was found in three of four LANA-FL and four of four LANA-NC immunoprecipitates.

Table S1.

Cellular proteins interacting with GFP-LANA-FL or GFP-LANA-NC (LANA Δ329–931) were identified by MS

| No. LANA-interacting proteins | proteins | LANA-FL | LANA-NC | ||||

| Times | Score | No. of peptide | Times | Score | No. of peptide | ||

| 1 | Lysine-specific demethylase 3A GN = KDM3A | 4 | 705.64 | 15 | 4 | 391.41 | 8 |

| 2 | Death domain-associated protein 6 GN = DAXX | 4 | 546.34 | 9 | |||

| 3 | Helicase-like transcription factor GN = HLTF | 4 | 329.48 | 7 | 4 | 557.17 | 12 |

| 4 | Sister chromatid cohesion protein PDS5 homolog A GN = PDS5A | 4 | 232.01 | 5 | 3 | 238 | 5 |

| 5 | FACT complex subunit SPT16 GN = SUPT16H | 4 | 122.89 | 3 | 4 | 408.91 | 9 |

| 6 | Core histone macro-H2A.1 GN = H2AFY | 4 | 94.27 | 2 | 4 | 182.28 | 3 |

| 7 | FACT complex subunit SSRP1 GN = SSRP1 | 4 | 89.26 | 2 | 4 | 166.94 | 3 |

| 8 | DNA repair protein complementing XP-C cells GN = XPC | 4 | 84.4 | 2 | 2 | 217.01 | 5 |

| 9 | Telomere-associated protein RIF1 GN = RIF1 | 3 | 412.85 | 7 | 4 | 979.53 | 19 |

| 10 | Mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein 1 GN = MDC1 | 3 | 275.37 | 7 | 4 | 958.41 | 19 |

| 11 | Isoform 2 of Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 GN = NUMA1 | 3 | 239.12 | 5 | 4 | 1,489.34 | 29 |

| 12 | Tyrosine-protein kinase BAZ1B GN = BAZ1B | 3 | 215.21 | 4 | 4 | 463.57 | 9 |

| 13 | SWI/SNF complex subunit SMARCC1 GN = SMARCC1 | 3 | 185.34 | 4 | 3 | 309.42 | 8 |

| 14 | AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A GN = ARID1A | 3 | 133.87 | 3 | 3 | 309.49 | 8 |

| 15 | Centromere protein F GN = CENPF | 3 | 130.02 | 3 | 4 | 667.49 | 14 |

| 16 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM6 GN = MCM6 | 3 | 112.59 | 2 | 2 | 123.32 | 3 |

| 17 | DNA repair protein RAD50 GN = RAD50 | 3 | 108.28 | 3 | 4 | 163.56 | 4 |

| 18 | DNA topoisomerase 2-α GN = TOP2A | 3 | 93.39 | 2 | 4 | 460.74 | 10 |

| 19 | cGMP-AMP synthase GN = MB21D1 | 3 | 358.11 | 8 | 4 | 391.26 | 9 |

| 20 | Metastasis-associated protein MTA1 GN = MTA1 | 3 | 201.35 | 4 | 2 | 143.84 | 3 |

| 21 | SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily E member 1 GN = SMARCE1 | 3 | 189.98 | 4 | 2 | 256.92 | 6 |

| 22 | Targeting protein for Xklp2 GN = TPX2 | 3 | 184.51 | 5 | 3 | 203.16 | 4 |

| 23 | PC4 and SFRS1-interacting protein GN = PSIP1 | 3 | 132.27 | 3 | 3 | 148.42 | 3 |

| 24 | Transcriptional repressor p66-alpha GN = GATAD2A | 3 | 130.53 | 3 | 1 | 89.37 | 2 |

| 25 | Putative oxidoreductase GLYR1 GN = GLYR1 | 3 | 120.92 | 2 | 3 | 119.51 | 2 |

| 26 | Torsin-1A-interacting protein 1 GN = TOR1AIP1 | 3 | 71.4 | 2 | 1 | 173.45 | 6 |

| 27 | Nucleosome-remodeling factor subunit BPTF GN = BPTF | 2 | 535.27 | 11 | 3 | 550.94 | 12 |

| 28 | Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 2 GN = G3BP2 | 2 | 350.51 | 8 | 3 | 401.69 | 8 |

| 29 | DNA topoisomerase 2-beta OS = Homo sapiens GN = TOP2B | 2 | 370.91 | 8 | 3 | 242.56 | 5 |

| 30 | Remodeling and spacing factor 1 GN = RSF1 | 1 | 272.61 | 6 | 3 | 212.41 | 4 |

| 31 | Partitioning defective 3 homolog GN = PARD3 | 1 | 450.03 | 10 | 3 | 168.1 | 4 |

| 32 | Actin-like protein 6A GN = ACTL6A | 2 | 202.72 | 4 | 3 | 112.8 | 2 |

| 33 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 (Fragment) GN = HNRNPD | 3 | 111.93 | 2 | |||

| 34 | Centrosomal protein of 170 kDa GN = CEP170 | 2 | 168.23 | 3 | 3 | 104.13 | 2 |

| 35 | Src substrate cortactin OS = Homo sapiens GN = CTTN | 2 | 230.8 | 4 | 3 | 495.72 | 11 |

| 36 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11 GN = PSMD11 | 1 | 102.16 | 2 | 3 | 111.26 | 2 |

| 37 | Ewing's tumor-associated antigen 1 GN = ETAA1 | 2 | 151.61 | 3 | 3 | 78.36 | 2 |

| 38 | SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A-like protein 1 GN = SMARCAL1 | 2 | 290.1 | 7 | 3 | 201.21 | 5 |

List contains proteins with high frequency (≥3 times in four independently repeated LANA-FL or LANA-NC precipitations).

The N-Terminal Domain of LANA Interacts with cGAS.

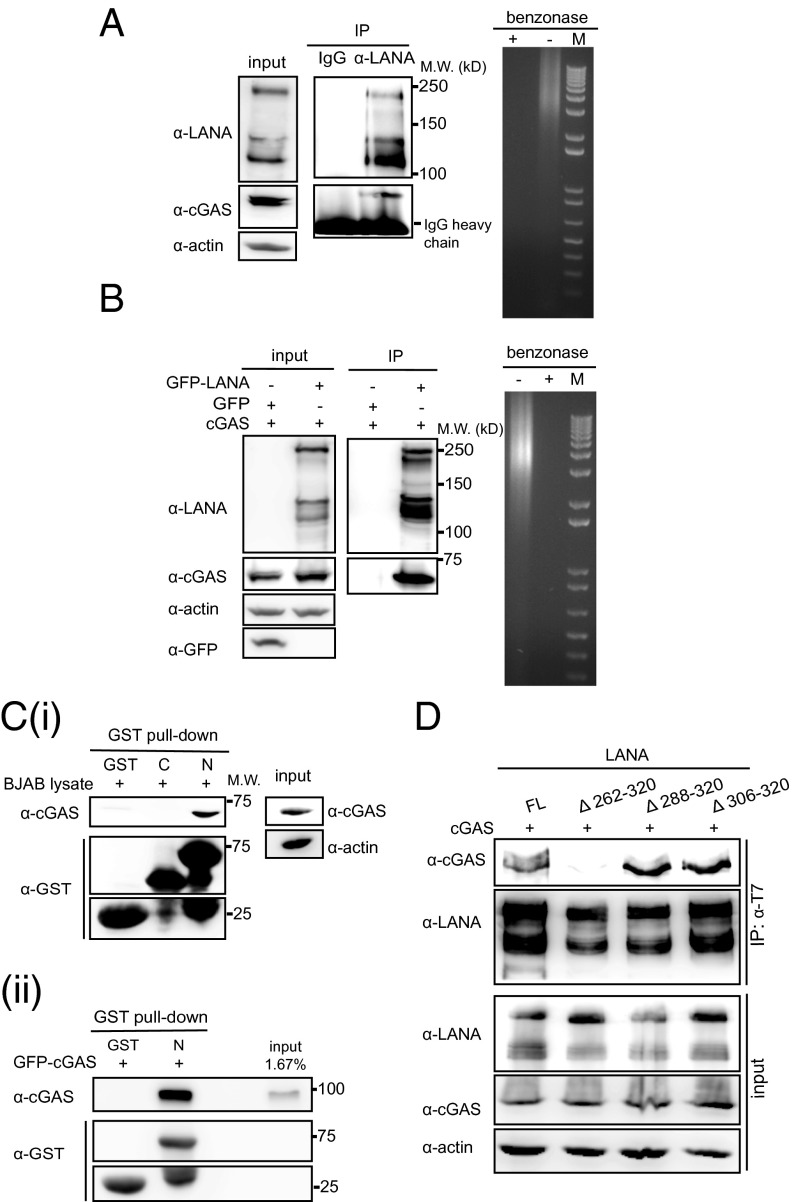

To confirm the interaction between endogenous LANA and cGAS, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) in the KSHV-positive PEL cell line BCBL-1, as well as a Co-IP in HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with LANA and cGAS. cGAS was coprecipitated with LANA from cell lysates treated with benzonase to exclude an involvement of cellular DNA in this interaction (Fig. 1 A and B). To identify which of the three domains of LANA (N- or C-terminal domain or internal repeat region) interact with cGAS, we performed GST pull-down assays with GST proteins fused to the C- or N-terminal domains of LANA and lysates of BJAB cells. This assay showed the N-terminal domain of LANA was sufficient for the interaction with cGAS (Fig. 1 C, i). We also performed a GST pulldown assay with GST protein fused to the N-terminal domain of LANA and an in vitro transcribed and translated GFP-tagged cGAS protein. This assay confirmed that the N-terminal domain of LANA was sufficient for the interaction of LANA and cGAS (Fig. 1 C, ii). To further confirm that this region of LANA is necessary for the interaction with cGAS, different internal deletion mutants in the N-terminal domain of full-length LANA (LANA Δ262–320, LANA Δ288–320, LANA Δ306–320) and full-length LANA (LANA FL) were cotransfected with cGAS (pUNO1-hcGAS) in HEK293T cells, and coimmunoprecipitations were performed. cGAS was coprecipitated with LANA Δ288–320 and LANA Δ306–320 mutants, but not with LANA Δ262–320 (Fig. 1D). This observation confirmed the results of the GST pull-down assay and points to the region of aa 262–320, within the N-terminal domain, as being required for the interaction with cGAS.

Fig. 1.

cGAS interacts with the N-terminal domain of LANA. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous cGAS and LANA in BCBL-1 cells. LANA was immunoprecipitated from benzonase-treated lysates of BCBL-1 cells with an antibody to the CR2 region of LANA (Fig. 5A) and immunoprecipitates stained on Western blots with antibodies to LANA (Upper, central panel) or cGAS (Lower, central panel). The presence of LANA and cGAS in the cellular lysates is shown on the Left and the degradation of cellular DNA by benzonase on the Right. (B) HEK293-T cells were cotransfected with an expression plasmid for cGAS (pUNO1-cGAS) together with pSERSeGFP-LANA FL or pSERSeGFP control vector. Cellular lysates were treated with benzonase and subsequently subjected to immunoprecipitation with a GFP specific antibody. (C) (i) Pull-down assay with GST fusion proteins consisting of the C-terminal domain of LANA (LANA-C), the N-terminal domain (LANA-N), and BJAB cell lysates. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for cGAS and GST. (ii) Pull-down assay with GST LANA-C or LANA-N fusion proteins and in vitro transcribed/translated GFP-cGAS recombinant protein. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibody specific for cGAS and GST (Ci). (D) HEK293-T cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids for cGAS together with N-terminally T7 epitope tagged full length LANA (LANA-FL) or the LANA mutants Δ262–320, Δ288–320, or Δ306–320. Forty-eight hours later, cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with a T7-specific antibody. Western blots were stained with anti-LANA (CR2-3), anti-cGAS, or for actin.

KSHV Reactivation Activates the cGAS-STING Axis.

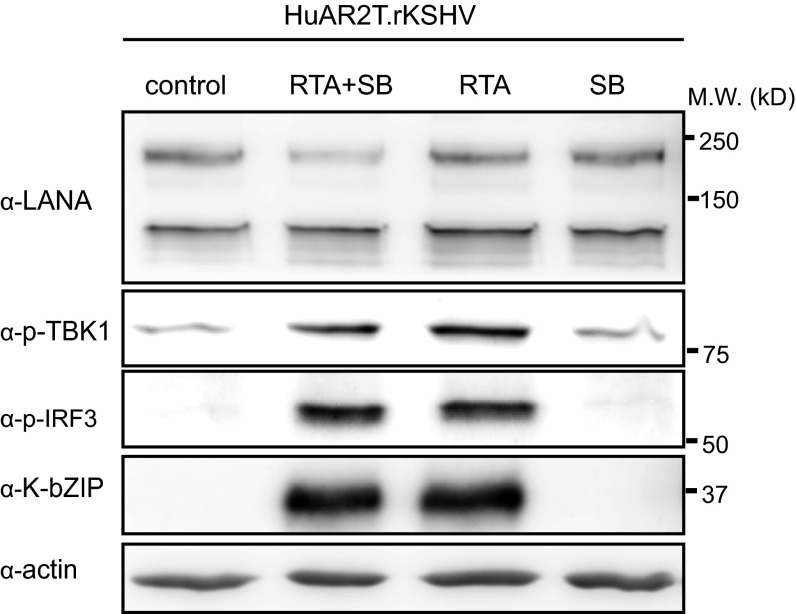

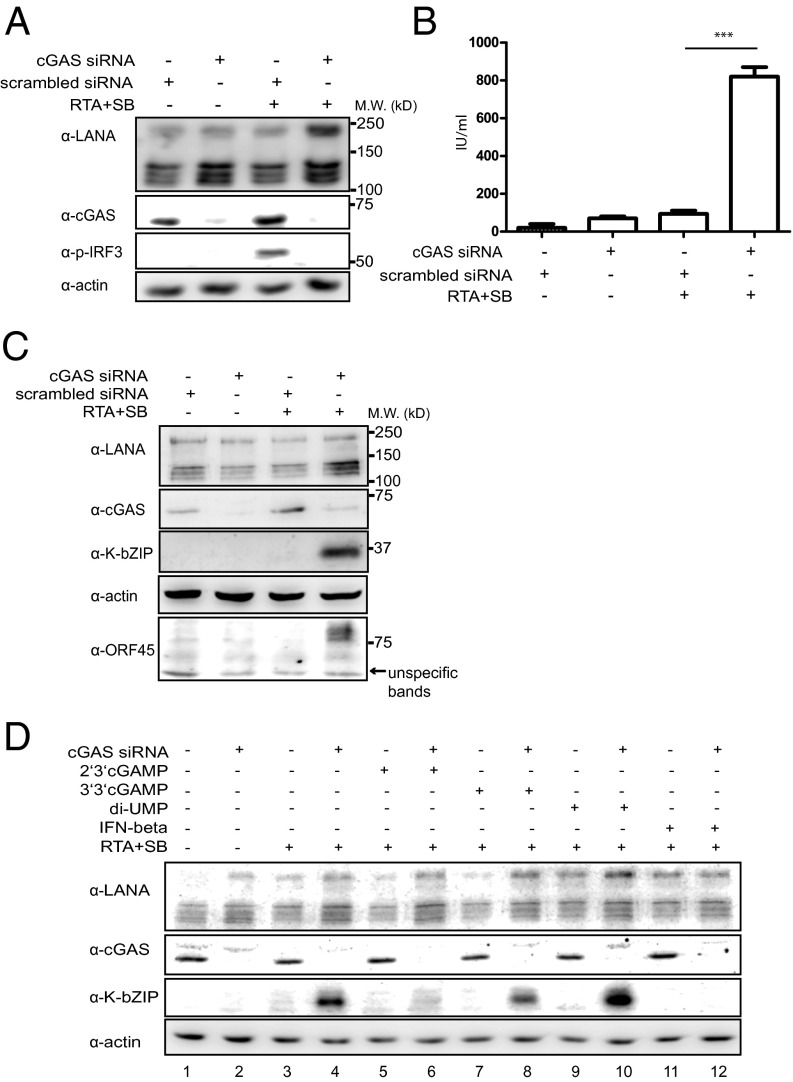

To investigate the role of cGAS in the KSHV lytic replication cycle, we silenced cGAS expression using siRNA in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219, a conditionally immortalized endothelial cell line (HuAR2T) persistently infected with recombinant KSHV.219 (51). We activated the lytic replication cycle by treatment with recombinant RTA and sodium butyrate, or recombinant RTA alone, and analyzed IRF3 phosphorylation as an indicator of the activation of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway. We found that IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation was efficiently induced on lytic reactivation (Fig. S2). When cGAS expression was silenced in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells, IRF3 phosphorylation was not observed after induction of the lytic cycle (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway is activated on KSHV reactivation in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219.

Fig. S2.

Lytic replication induction of KSHV activates the cGAS-dependent signaling pathway. HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 was treated with a baculovirus expressing the KSHV RTA protein and 1.5 mM Na-butyrate, the baculovirus expressing the KSHV RTA alone, or Na-butyrate alone. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using antibodies to p-IRF3, p-TBK1, and the KSHV K-bZIP protein.

Fig. 2.

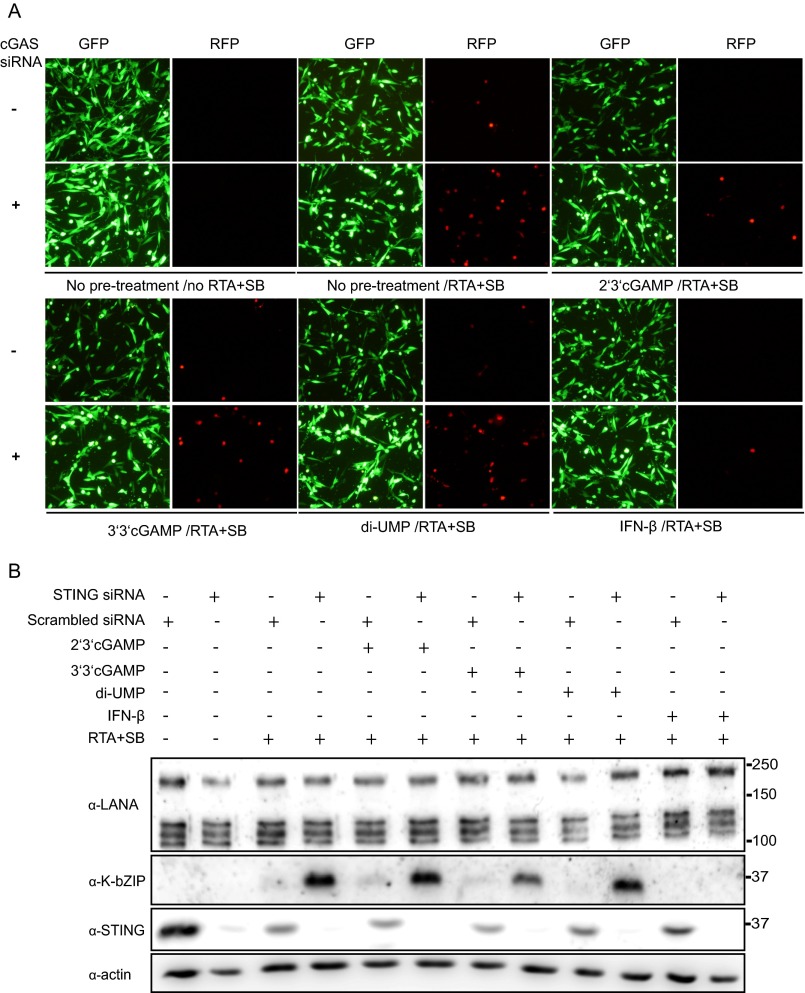

Silencing of cGAS increases KSHV reactivation. (A) HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were transfected with an siRNA targeting cGAS or scrambled siRNA as control and 24 h hours later the lytic replication cycle of KSHV was induced by addition of baculovirus expressing the KSHV RTA protein and 1.5 mM Na-butyrate. Forty-eight hours later, supernatants were collected for analysis of viral titers, and cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. (B) Supernatants collected as described in A were titered on HEK293T cells. Infectious units per milliliter are shown. (C) HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were transfected with an siRNA targeting cGAS or scrambled siRNA as control, and 24 h hours later, the lytic replication cycle of KSHV was induced by addition of baculovirus expressing the KSHV RTA protein and 1.5 mM Na-butyrate. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting analysis using antibodies to cGAS, the early lytic protein K-bZIP, and the ORF45-endoded viral tegument protein. (D) HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were transfected with an siRNA targeting cGAS or scrambled siRNA. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with 2′3′-cGAMP, 3′3′-cGAMP, di-UMP, or IFN-β, and 12 h later, the lytic replication cycle of KSHV was induced by addition of baculovirus expressing the KSHV RTA protein and 1.5 mM Na-butyrate (lanes 3–12) or cells were left untreated (lanes 1–2). Cells were lysed 48 h later and subjected to immunoblotting analysis.

Both cGAS and STING Inhibit KSHV Reactivation.

Because we observed that the cGAS-STING-IRF3 pathway is activated during reactivation, we next analyzed whether activation of this pathway has an effect on the KSHV lytic replication cycle. To measure the level of reactivation in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells, the expression of an early lytic viral protein K-bZIP, as well as a viral tegument protein ORF45, was measured by Western blot. Additionally, the number of cells expressing lytic viral genes was ascertained by monitoring the expression of RFP, which is driven by a KSHV lytic promoter (PAN promoter) in the recombinant rKSHV.219 (52), which is present in the HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cell line. We also measured the virus titer in the culture medium of HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells. We observed an increase in the release of infectious KSHV progeny from reactivated HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells after treatment with cGAS siRNA (Fig. 2B), as well as an enhanced expression level of K-bZIP and ORF45 (Fig. 2 C and D, compare lanes 3 and 4), and an increased number of RFP-positive cells (Fig. S3A). These results suggest that the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway is important to suppress KSHV reactivation from latency in KSHV-infected cells.

Fig. S3.

Knockdown of cGAS or STING increases KSHV reactivation. (A) Representative images of HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells pretreated with siRNA to cGAS or control siRNA before the activation of the lytic replication cycle with recombinant RTA and Na-butyrate and treated with 2′3′cGAMP, 3′3′cGAMP, diUMP, or IFN-β, as described in Fig. 2D. GFP channel, cells harboring latently infected KSHV; RFP channel, KSHV reactivated cells. (B) HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were transfected with STING or scrambled siRNAs. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with 2′3′-cGAMP, 3′3′-cGAMP, di-UMP, or IFN-β, and about 12 h later, the lytic cycle was induced with baculovirus exprssing RTA and Na-butyrate. Forty-eight hours later, cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting.

To confirm that the cGAS-mediated DNA sensing pathway is important for the control of viral reactivation, we assessed the effect of cGAMP and IFN-β on KSHV reactivation. 2′3′cGAMP, a unique class of the 2′-5′linked second messenger molecule, is produced by cGAS on DNA binding and then binds to and activates STING. It has a higher affinity for human STING than 3′3′cGAMP (38, 40). Unlike 2′3′cGAMP and 3′3′cGAMP, cyclic di-uridine monophosphate (c-di-UMP) is not able to bind STING. When we pretreated HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells with 2′3′cGAMP, 3′3′cGAMP, c-di-UMP, or IFN-β before induction of the lytic cycle, we found that 2′3′cGAMP is able to inhibit KSHV reactivation in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells, in which cGAS had been silenced by siRNA, as assessed by expression of the early protein K-bZIP and the RFP marker (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 4 and 6, and Fig. S3A). Pretreatment with 3′3′cGAMP only moderately inhibited K-bZIP expression, and pretreatment with c-di-UMP had no effect, whereas pretreatment with IFN-β completely repressed KSHV reactivation (Fig. 2D and Fig. S3A). The above results indicate that cGAS and its second messenger molecule 2′3′cGAMP prevent KSHV reactivation and play a role in the maintenance of viral latency.

Next, we tested whether STING, a downstream mediator of cGAS and 2′3′cGAMP, also contributes to inhibition of lytic KSHV reactivation. Similarly to cGAS, we found that knockdown of STING enhanced KSHV reactivation, as measured by the increased level of K-bZIP in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 (Fig. S3B). After knockdown of STING, pretreatment with 2′3′cGAMP, which binds to STING and induces STING trafficking and signaling, had no effect on viral reactivation as expected, nor did 3′3′cGAMP or di-UMP. In contrast, pretreatment with IFN-β, which acts downstream of STING, was still able to block viral reactivation (Fig. S3B). These results confirm that the activation of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway and the resulting production of IFN-β prevent KSHV reactivation and help to maintain KSHV latency.

The Cytoplasmic Isoforms of LANA Interact with cGAS.

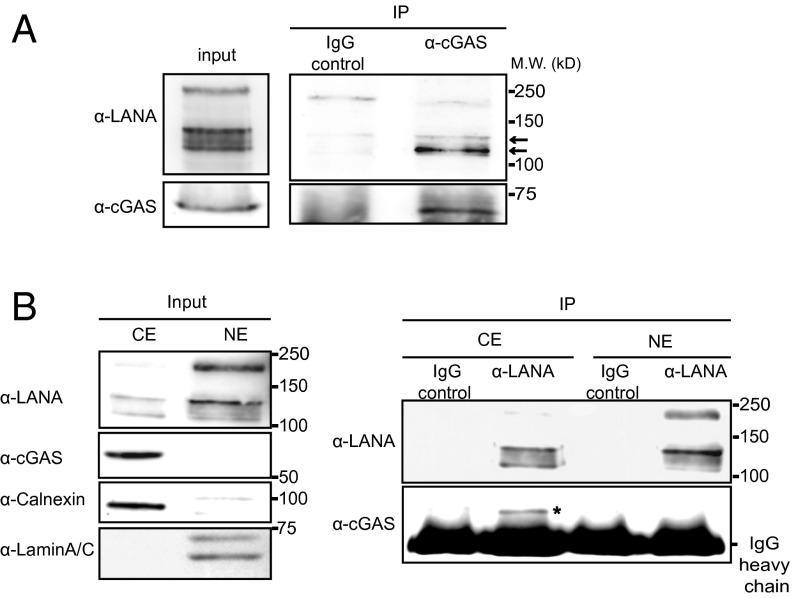

LANA is known to be a nuclear protein forming nuclear speckles in KSHV-infected cells. A recent study reported the existence of cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA, which are mainly generated by noncanonical internal translation initiation sites localized within the LANA N-terminal domain (35). Another recent report suggested the existence of N-terminally truncated LANA forms resulting from caspase cleavage (24). In a complementary experiment to that shown in Fig. 1A (coimmunoprecipitation of cGAS by LANA with a LANA-specific antibody), we immunoprecipitated cGAS with a cGAS specific antibody from BCBL-1 cells and found that mainly lower-molecular-weight isoforms of LANA associated with cGAS [Fig. 3A; compare immunoprecipitated LANA bands (Right) with LANA bands in the input cell lysate (Left)]. This result suggests that cGAS might preferentially interact with the short cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA. To verify this hypothesis, we fractionated lysates of BCBL-1 cells into cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts. cGAS is known to localize to the cytoplasm, and as expected, we detected its expression in the cytosolic extract, but not in the soluble nuclear extract (Fig. 3B, Left). In the cytoplasmic extract we detected mainly the short isoforms of LANA, whereas full-length LANA was predominantly in the nuclear extract (Fig. 3B, Left). When we used an antibody recognizing an epitope within the internal repeat region of LANA for coimmunoprecipitations with the BCBL-1 cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions and analyzed the immunoprecipitates with an antibody to LANA by Western blotting, we observed short LANA isoforms in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B, Right). Interestingly, cGAS coprecipitated with the short isoforms of LANA in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B, Right). These results suggest that mainly the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA interact with cGAS.

Fig. 3.

cGAS interacts with the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA. (A) BCBL-1 cells were lysed, and endogenous cGAS was immunoprecipitated with a cGAS-specific antibody or IgG as negative control. Input lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with LANA and cGAS-specific antibodies. Arrows indicate the shorter isoform of LANA. (B) BCBL-1 cells were lysed, and nuclear (NE) and cytoplasmic (CE) extracts were prepared. NE and CE were analyzed by immunoblotting (Left). CE and NE were immunoprecipitated with a LANA-specific antibody or IgG as control and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to LANA and cGAS (Right). *cGAS coprecipitates with the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA in the cytoplasmic extract.

The Cytoplasmic Isoforms of LANA Antagonize the Function of cGAS.

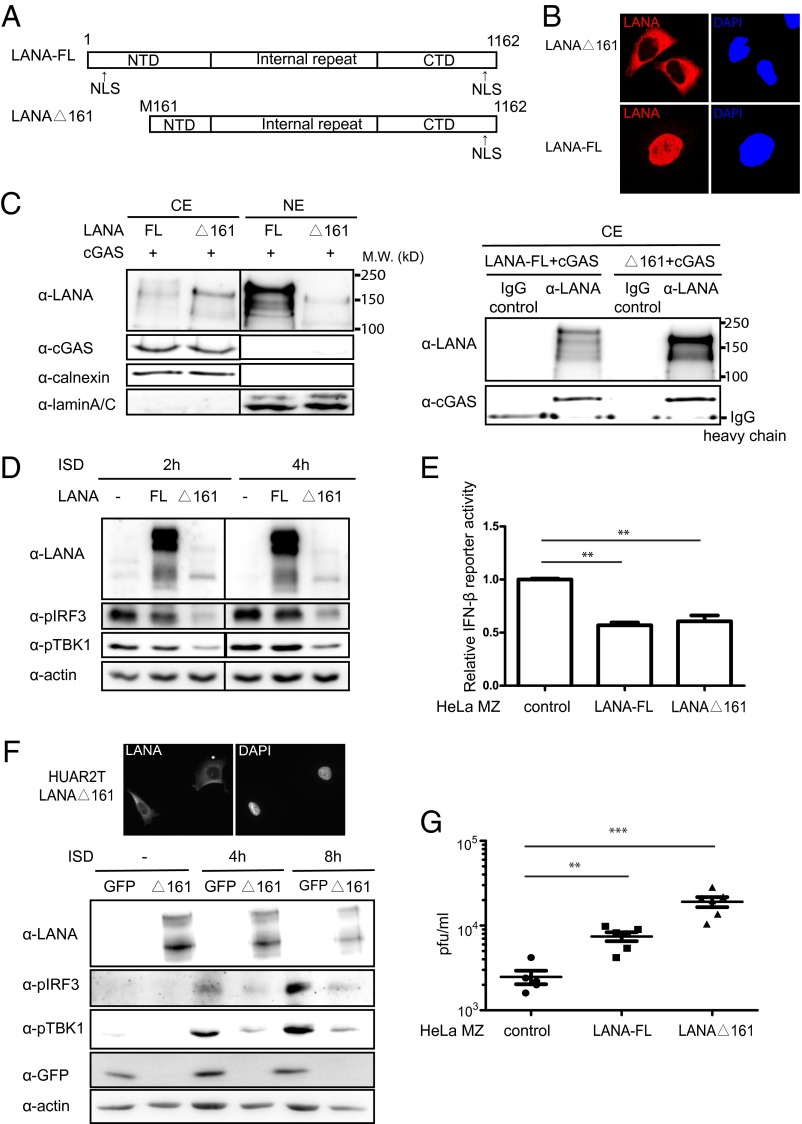

To determine whether the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA antagonize cGAS function, we first analyzed the interaction of cGAS with an N-terminally truncated and therefore cytoplasmic LANA mutant, LANAΔ161 (aa161–1162) (Fig. 4 A and B). On cotransfection of cGAS and LANAΔ161 in HEK293T cells and coimmunoprecipitation with a LANA antibody, we could confirm that LANAΔ161, which only localizes to the cytoplasm (Fig. 4 B and C, Left, and F, Upper), interacted with cGAS (Fig. 4C, Right).

Fig. 4.

A cytoplasmic isoform of LANA antagonizes cGAS-dependent IFN-β signaling and antiviral activity. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length LANA (LANA-FL) and the cytoplasmic LANA mutant LANAΔ161, which starts at the internal methionine 161. (B) Representative images of HeLa MZ-LANA FL and HeLa MZ LANAΔ161 stable cell lines. Cells were fixed and probed with a LANA antibody and stained with Hoechst to visualize nuclei. (C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with cGAS and LANA-FL or LANAΔ161. Cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, and input samples were analyzed by immunoblotting analysis (Left). The cytoplasmic extracts were immunoprecipitated with a LANA-specific antibody or IgG as control and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to LANA and cGAS (Right). (D) HeLa-MZ cells stably expressing LANA-FL or LANAΔ161 were stimulated with ISD or transfection reagent as the control. Lysates were generated 2 and 4 h later and analyzed by immunoblotting. (E) IFN-β promoter luciferase reporter assay in HeLa MZ cells stably expressing LANA FL or LANAΔ161, transfected with an IFN-β promoter reporter construct. The value of the relative reporter activity of parental control is normalized and set to 1. (F) Cytoplasmic localization of LANAΔ161 in HuAR2T cells transduced with a lentiviral vector for LANAΔ161. Cells were fixed, and LANA was visualized with a LANA antibody; nuclei were stained with DAPI (Upper). Cells were stimulated by ISD transfection or transfection reagent as control, and lysates were prepared 4 and 8 h later for immunoblotting analysis. (G) HeLa MZ cells stably expressing LANA-FL or LANAΔ161 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.1. Supernatants were collected 36 h after infection, and viral titers were measured by plaque assay on Vero cells. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Student t test.

Among the HeLa cell lines of different origins tested in our laboratory, HeLa MZ cells were found to express both cGAS and STING. The cGAS-STING-IRF3 pathway can be efficiently activated in HeLa MZ cells on IFN stimulatory DNA (ISD) transfection, as indicated by the detection of IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4D and Fig. S4). To test whether LANAΔ161 can counteract cGAS activity, we generated HeLa MZ cell lines stably expressing LANAΔ161 and full-length LANA (LANA FL). As shown in Fig. 4B, LANAΔ161 is localized in the cytoplasm, whereas LANA FL is found in the nucleus. We induced the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway in HeLa cell lines by transfection with ISD and found that the presence of LANAΔ161 strongly inhibited both IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation, compared with the activation seen in parental and LANA FL-expressing HeLa MZ cells (Fig. 4D and Fig. S4).

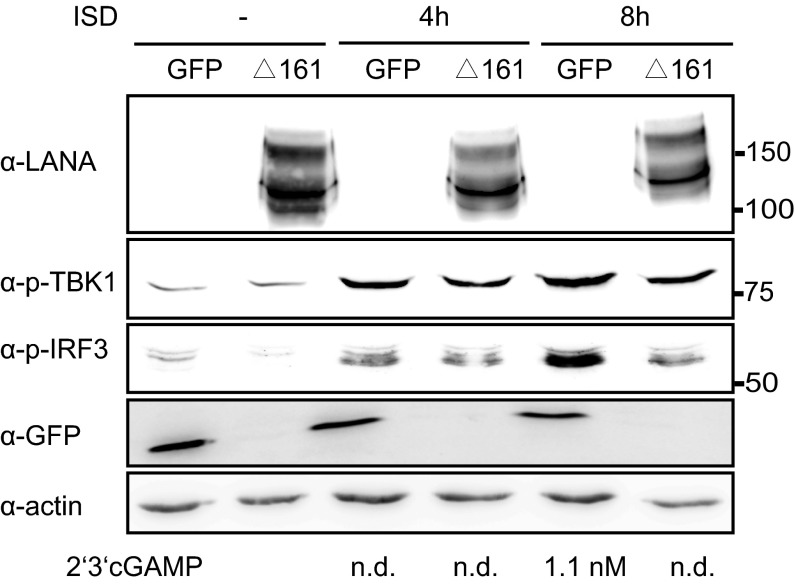

Fig. S4.

The cytoplasmic isoform of LANA inhibits 2′3′cGAMP production. HeLa MZ cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing LANAΔ161 or GFP were stimulated by transfection with ISD. Four and 8 h after stimulation, 2′3′-cGAMP was quantified by RP-HPLC/MS. Cells were lysed and the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway was verified by immunoblotting with antibodies to phosphorylated TBK1 and IRF3. Low levels of 2′3′-cGAMP could only be detected after 8 h of ISD stimulation in cells expressing GFP, but not in cells expressing LANAΔ161. Amounts of 2′3′-cGAMP (nM) measured are shown below the actin immunoblot.

Next, we transiently transfected HeLa MZ-LANAΔ161 or LANA FL with an IFN-β promoter luciferase reporter plasmid and found that both LANA FL and the cytoplasmic LANA mutant LANAΔ161 were able to repress the transcriptional activation of the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 4E). This observation is in line with the recently published screen of KSHV ORFs, which showed that full-length LANA can inhibit the activation of an IFN-β reporter in response to cGAS stimulation (21).

To provide further evidence that cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA can negatively modulate cGAS activity, we generated a stable HuAR2T cell line expressing LANAΔ161 by lentiviral transduction. HuAR2T cells stably transduced with eGFP served as control. As shown in HeLa MZ cells, LANAΔ161 was localized in the cytoplasm of transduced HuAR2T cells (Fig. 4F). We next induced the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway by ISD transfection and found that LANAΔ161 inhibited IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation compared with HuAR2T cells stably expressing eGFP (Fig. 4F). Together, these results indicate that a cytoplasmic isoform of LANA interacts with cGAS and antagonizes the ability of cGAS to initiate an innate immune response resulting in IFN-β production.

After the induction of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway by transfection of ISD in HeLa MZ cells stably expressing LANAΔ161 or GFP, we also quantified the level of 2′3′cGAMP produced in these cells by RP-HPLC/MS. We did not detect 2′3′cGAMP from HeLa MZ cells expressing LANAΔ161 after ISD transfection, compared with a low amount of 2′3′cGAMP detected in the cells expressing GFP at 48 h after ISD transfection, which is consistent with the observation of reduced IRF3 phosphorylation in HeLa MZ cells expressing LANAΔ161 (Fig. S4). These results confirm that the cytoplasmic isoform of LANA antagonizes cGAS function and inhibits the subsequent 2′3′cGAMP and type I interferon production.

To address the biological significance of this observation, we took advantage of the observation that cGAS can restrict HSV-1 replication (42, 43). We infected the LANA FL and LANAΔ161 expressing HeLa MZ cell lines with HSV-1 at an MOI (multiplicity of infection) of 0.1 and measured the levels of newly produced viral progeny in the cell culture supernatant by plaque assay on Vero cells. As shown in Fig. 4G, in HeLa MZ cells expressing LANAΔ161, we found markedly (∼10-fold) enhanced HSV-1 replication, in line with the ability of LANAΔ161 to inhibit IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation, whereas LANA FL did so only moderately (∼4-fold). Together, our findings suggest that a cytoplasmic isoform of LANA can antagonize the cGAS-mediated innate immune response and thereby promote productive herpesviral replication.

Expression of Cytoplasmic LANA Isoforms Is Increased on Lytic Reactivation of KSHV.

Because LANA is known to be required for the establishment and maintenance of KSHV latency (47, 48, 53), a role for the cytoplasmic forms of LANA to promote productive (lytic) herpesviral replication seems at first counterintuitive. We therefore examined whether expression of the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA, shown here to antagonize cGAS, could increase following activation of the lytic replication and thereby promote the progression of the lytic replication cycle.

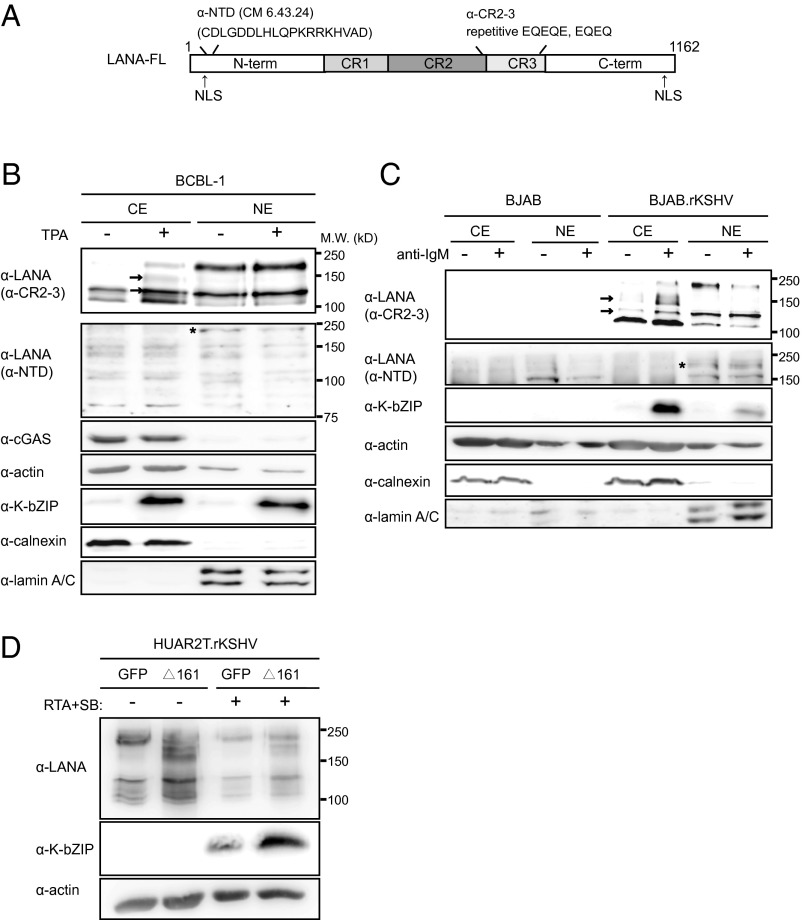

As shown in Fig. 5B, induction of the lytic replication cycle by TPA in BCBL-1 cells resulted in increased expression of lower-molecular-weight forms of LANA in the cytoplasm of fractionated cells, which were detected by an antibody to the internal repeat region of LANA (anti-CR2-3), but not with an antibody to an epitope in the N-terminal domain (NTD) of LANA (anti-NTD) (Fig. 5 A and B). Similarly, induction of the lytic replication cycle in a persistently KSHV-infected BJAB B-cell line, BJAB.rKSHV.219 (54, 55), with an antibody to surface IgM was also accompanied by the increased expression of short isoforms of LANA in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 5C). As observed for BCBL-1 cells, these inducible cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA were only detected with the anti–CR2-3 LANA antibody, but not with the anti-NTD LANA antibody (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that the N-terminal end of full-length LANA (LANA FL), which contains a nuclear localization signal, is lacking in the inducible cytoplasmic forms of LANA.

Fig. 5.

Increased expression of cytoplasmic LANA isoforms following lytic reactivation of KSHV and enhancement of lytic replication by a cytoplasmic LANA isoform. (A) Schematic representation of LANA showing epitopes detected by the anti-LANA antibodies anti-CR2-3 and anti-NTD (CM 6.43.24). (B and C) Immunoblotting showing the expression of LANA isoforms in the cytoplasmic (CE) and nuclear (NE) extracts after lytic cycle induction by TPA (24 h) in BCBL-1 cells (B) and after lytic cycle induction by anti-IgM antibody (24 h) in BAJB.rKSHV.219 and the control cell line BJAB (C). LANA isoforms were detected by an antibody to the CR2-3 domains in the internal repeat region of LANA (Top) and an antibody to an amino-terminal epitope (second panel from the top). Arrows, cytoplasmic LANA bands increasing after lytic reactivation; asterisk, full-length, nuclear LANA isoform. (D) HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells transduced with a lentivirus expressing LANAΔ161 or GFP were treated with baculovirus expressing RTA and Na-butyrate to induce the lytic cycle or left untreated. Lysates were analyzed 36 h later by immunoblotting.

To investigate whether the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA might facilitate lytic replication by antagonizing cGAS, we transduced HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells with LANAΔ161 or eGFP-expressing lentiviruses and activated KSHV lytic replication with RTA and sodium butyrate. We observed enhanced levels of the KSHV early protein K-bZIP in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 expressing LANAΔ161 after reactivation, compared with the GFP-expressing control HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cell line (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA might enhance viral lytic replication by an inhibition of the cGAS-dependent signaling pathway in LANAΔ161 expressing cells (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

As one of the major viral proteins expressed in KSHV latency, the function of LANA in the nucleus of KSHV-infected cells has been well studied. In contrast, the function of the recently discovered cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA, generated by noncanonical translation initiation within the LANA NTD (35, 56) or possibly by caspase cleavage (24), has not been explored to date. In this study, we report that LANA, especially its cytoplasmic isoforms, antagonizes the function of cGAS, hereby promoting lytic replication after lytic cycle induction.

Following our initial observation that LANA interacts with cGAS, we show that this interaction occurs mainly in the cytoplasm of KSHV-infected cells and that cGAS immune-precipitated from the cytoplasm is associated with lower-molecular-weight forms of LANA (Fig. 3). We found that overexpression of one of the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA, lacking amino acids 1–160, reduced IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation levels during ISD stimulation in HeLa MZ and HuAR2T cells and inhibited IFN-β promoter activity in an IFN-β luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 4 and Fig. S4). We also show that expression of this cytoplasmic isoform of LANA enhances HSV-1 replication and KSHV reactivation (Figs. 4G and 5D). Together these results suggest that, during lytic replication, the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA antagonize the activity of cGAS in the cGAS-STING-IRF3 pathway and reduce the phosphorylation of IRF3 and TBK1 and thereby production of type I IFNs, which, in turn, further enhances viral lytic replication. Indeed, in keeping with this interpretation of our finding, we observed that the expression of several cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA increases on lytic cycle induction by TPA in BCBL-1 cells and by anti-IgM in BJAB.rKSHV.219 cells. This result suggests that the translation of LANA mRNA is regulated differently during latency and lytic reactivation, with the start codon in position 1 of ORF73 being used during latency and internal initiation codons coming into play during the lytic cycle. It has been shown that expression of LANA can be directed from two different promoters that generate different 5′ UTRs of LANA mRNA. Although the constitutive (latent) promoter generates a longer 5′ UTR that occurs in a spliced or unspliced form, the lytic LANA promoter, localized in the intron within the LANA 5′ UTR, directs the expression of an unspliced mRNA with a shorter 5′ UTR (4, 57, 58). One could envisage that the shorter 5′ UTR generated during lytic reactivation could favor, as a result of a different RNA structure fold, the use of internal start codons in the LANA NTD and thereby the generation of LANA variants lacking the N-terminal NLS (4, 5), which localize to the cytoplasm. This hypothesis will have to be addressed experimentally in the future. Our conclusion that, during KSHV lytic reactivation, the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA antagonize cGAS activity and inhibit the subsequent production of IFN-β, thereby further facilitating lytic replication, highlights the role of the IFN system in regulating herpesviral latency and the role of cGAS as a cellular determinant of KSHV latency.

We observed robust viral reactivation on knockdown of cGAS or STING in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219, as shown by enhanced expression of the early lytic viral gene K-bZIP and viral progeny production (Fig. 2). Pretreatment with 2′3′cGAMP or IFN-β before reactivation was able to repress or completely inhibit viral lytic replication. These results suggest that activation of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 pathway and the resulting IFN-β production restrict KSHV reactivation and therefore play an important role in the maintenance of viral latency from reactivation. There are several lines of evidence supporting a role for type I IFNs in supporting persistent viral infections. MHV-68 replicates more efficiently from macrophages of IFN-γ receptor-deficient mice and from splenocytes of IFN-α/β receptor-deficient mice (59–61). IFN-α also promoted the establishment of HSV-1 latency and pseudorabies virus (PRV) in vitro in neurons of the trigeminal ganglion (62). IFN-β could block MCMV reactivation in mice latently infected with MCMV (63). Chronic IFN-I signaling was also reported to be associated with LCMV persistence (64–66). After the viruses successfully establish viral latency, the IFN-I signaling may contribute to virus persistence. We therefore hypothesize that IFN-α/β may not only control γ-herpesviruses, but also play an important role in the maintenance of viral latency.

If, as our findings suggest, the role of cytoplasmic LANA isoforms is to antagonize cGAS and thereby promote lytic replication, this raises the question of how cGAS is activated in KSHV-infected cells. We did not observe spontaneous reactivation in HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 in the absence of cGAS without lytic replication induction (Fig. 2), suggesting that lytic replication is necessary for cGAS activation. During the viral lytic replication cycle, newly synthesized viral DNA is incorporated into capsids, which are then transported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. It is conceivable that viral DNA leaking from imperfectly assembled capsids might be recognized by cGAS and trigger the activation of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway. Other possibilities include the leakage of viral or host DNA into the cytosol due to cell death during KSHV reactivation, which may be recognized by cGAS and thereby activate this innate response. DNA fragmentation and cell death by apoptosis were observed during KSHV reactivation in PEL- and KSHV-infected telomerase-immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (TIVEs) (67–69). Fragmented DNA due to DNA damage might accumulate in the cytoplasm and initiate DNA sensing (70). The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) instability induced by herpesviruses can also induce the cGAS-STING-IRF3–mediated antiviral innate immune response (71). Interestingly, the RIG-MAVS signaling pathway was also activated during KSHV reactivation, and dsRNA was detected during viral reactivation in latently KSHV-infected iSKL cells (72). Activation of the cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling pathway may therefore be part of a larger surveillance network that responds to viral nucleic acids in the cytoplasm of infected cells and against which KSHV may have evolved countermeasures. Our observation that the cytoplasmic isoforms of LANA may serve as a viral antagonist of cellular innate immunity extends the role of LANA into the lytic replication cycle and could provide an explanation both for the existence of a lytic LANA promoter and the recently described initiation of alternative forms of LANA at internal start codes in its N-terminal domain.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents.

HEK293T, Vero, and HeLa MZ cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin. BJAB and BCBL-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) FCS, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin. HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 is an endothelial cell line (HuAR2T) conditionally immortalized by human telomerase RT and SV40 large T antigen and stably infected with rKSHV.219 (51). HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were maintained in EGM-2MV medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin, in the presence of 1 µg/mL doxycycline and 4.2 µg/mL puromycin.

2′3′-cGAMP (tlrl-cga23-s), 3′3-cGAMP (tlrl-cga-s), c-di-UMP (tlrl-cdu), ISD (tlrl-isdn), and pUNO1-hCGAS (MB21D1) were purchased from Invivogen and human IFN β1a (11415-1) from PBL Assay Science.

Immunoblotting.

The following antibodies were used to detect proteins after separation by SDS/PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes: anti-LANA CR2-3 (13-210-100; Advanced Biotechnologies), anti-LANA NTC (CM 6.43.24; a kind gift from Y. Chang and P. Moore, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh), anti-cGAS (HPA031700-100UL; Sigma), anti-TMEM173/STING (LS-C108557; LSBio), anti–phospho-IRF3 (4947S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–phospho-TBK1/NAK (Ser172) (5483S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-T7 Tag (69522-3; Novagen); anti–K-bZIP (sc-69797; Santa Cruz), anti-calnexin (C-20) (sc-6465; Santa Cruz), anti–β-actin (A5441; Sigma), and anti-lamin A/C (2032S; Cell Signaling Technology). As a negative control in immunoprecipitation experiments, rat IgG2c isotype control [SB68b] (GTX35063; Genetex) and normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz) were used.

In Vitro Translation and GST Pulldown Assay.

GFP-cGAS cloned into the pIRESneo3 vector containing a T7 promoter (kindly provided by A. Ablasser, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland) was transcribed and translated in vitro using the TNT rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). GST-fused N-LANA or GST alone were produced in Escherichia coli Rosetta and bound to glutathione beads. Equivalent amounts of GST proteins were incubated with 20 µL in vitro-translated cGAS, and the reaction volume was brought up to 300 µL by TBST lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Proteins were incubated overnight at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. The beads were washed six times with TBST lysis buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with 10 µL 5× SDS sample buffer, boiled 5 min, and analyzed by Western blot.

Construction of Lentiviral Vectors.

The full-length LANA-FL construct was amplified by PCR from BAC36 with the following primers: LANA Avrll forward, TAT CCT AGG GCG CCC CCG GGA ATG CGC; LANA NotI reverse, TAT GCG GCC GCT TAT GTC ATT TCC TGT GGA GAG TC.

The LANA-NC construct (LANA lacking the internal repeat, aa 329–931) was obtained by PCR from pcDNA3.1-LANA-NC, which was originally cloned from BAC36 LANAΔ329–931 (47) with the following primers: LANA Avrll forward, TAT CCT AGG GCG CCC CCG GGA ATG CGC; ACL NotI reverse, ATT TGC GG CCG CTT ATG TCA TTT CCT GTG GAG. Both LANA-NC and LANA-FL inserts were first cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems; Promega), and subsequently excised with AvrII and NotI to allow ligation into the doxycycline-inducible lentiviral vector pSERS-GFP. Lentiviral vectors generated were designated pSERS-GFP-LANA-NC and pSERS-GFP-LANA-FL. LANAΔ161 was amplified by PCR from plasmid pcDNA3.1 (+)/Zeo/LANAΔ161 (kindly provided by P. Moore) with the following primers: LANAΔ161forward, CTCGTAAAGTCGACACCATGCGTCCGCCACCCTCG; LANAΔ161reverse, GGACTAATCCGGAGCTTATGTCATTTCCTGTGGAGAGTCCCC); this was inserted into the lentiviral vector pSERS-eGFP, which was digested with NcoI and NotI, according to the protocol of Gibson Assembly (Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit, #E5510S; NEB). The generated lentiviral vector was designated pSERS-LANAΔ161.

Lentivirus Production and Generation of Stable Cell Lines.

The expression vector for the RD114 envelope protein, M57-DAW (lentiviral gag/pol), kindly provided by J. Bohne (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany) and lentiviral vectors pSERS-GFP, pSERS-GFP-LANA-NC, or pSERS-GFP-LANA-FL were cotransfected into HEK293-T cells using the calcium phosphate method. The supernatant containing virus particles was harvested every 12 h after transfection for 60 h and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 14 h at 4 °C using a SW32 rotor in a Beckmann ultracentrifuge. The supernatant was sucked off gently, and ∼200 µL medium was left. The pellet was resuspended in this medium, and aliquots were stored at −80 °C.

BCBL-1 cells (5×104) were seeded per well of a 24-well-plate and infected with 100 µL concentrated pseudotyped lentiviral stocks pSERS-GFP, pSERS-GFP-LANA-NC, or pSERS-GFP-LANA-FL by centrifuging for 30 min at 450 × g at 32 °C. The medium was changed after an incubation time of 5 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Doxycycline (1 µg/mL) was added to the cells 24 h after transduction. The transduced cells were expanded, grown in the presence of 1 µg/mL doxycycline, and sorted for GFP-positive cells by FACS. The resulting transduced cell lines were named BCBL-1 GFP, BCBL-1 GFP-LANA-NC, and BCBL-1 GFP-LANA-FL and cultured in the presence of 1 µg/mL doxycycline.

HuAR2T (1×105) or HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were seeded in 12-well plates 1 d before transduction. The cells were transduced with 200 µL concentrated pseudotyped retrovirus stocks containing pSERSeGFP or pSERSLANAΔ161 by centrifuging at 450 × g for 30 min at 32 °C. After centrifugation, 200 µL fresh EGM-2MV medium was added to each well, and 4 h later, the medium was changed and replaced with 1 mL EGM-2MV medium. The transduced HuAR2T and HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells were named HuAR2T-eGFP, HuAR2T-LANAΔ161, HuAR2T.rKSHV.219-eGFP, and HuAR2T.rKSHV.219-LANAΔ161 and cultured in EGM-2MV medium with 1 µg/mL doxycycline.

HeLa MZ cells transduced with pSERS-eGFP or pSERS-LANAΔ161 were generated in a similar manner as the HuAR2T cells and named HeLa MZ-pSERS-eGFP and HeLa MZ-pSERS-LANAΔ161.

To generate stable HeLa MZ cell transfectants, 8 × 104 HeLa MZ cells were seeded per well of six-well plate and transfected with 2 µg/well of pcDNA3.1/Zeo+/LANA FL or pcDNA3.1/Zeo+/LANAΔ161 with Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (11668-019; Invitrogen). The medium was changed 6 h after transfection, and 24 h later, the transfected cells were selected with 100 µg/mL Zeocin. The selected cell clones were grown in the presence of Zeocin and named HeLa MZ-LANA FL and HeLa MZ-LANAΔ161.

LC-MS Sample Preparation, Data Processing, and Statistical Analysis.

Cells (1.5 × 108) from each stable cell line (BCBL-1 GFP, BCBL-1 GFP-LANA-FL, BCBL-1 GFP-LANA-NC) were washed once in PBS and resuspended in buffer A (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors) for 30 min on ice and homogenized with 15 strokes in a cell douncer (73). Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 1,200 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5417R, rotor F45-30-11, Hamburg, Germany) and 4 °C and resuspended in 2 mL TBST lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% TritonX-100). The suspension of nuclei was kept cold and vortexed vigorously. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5417R, rotor F45-30-11, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min and precleared by incubation with 50 µL protein A beads (Protein A Sepharose 4 Fast flow; GE Healthcare) or GFP-trap control beads (GFP-Trap A; Chromotek) for 1 h at 4 °C on a rolling platform. Beads were removed by centrifugation, and precleared samples were incubated with 50 µL beads to which an anti-GFP antibody had been conjugated (Living Colors full-length GFP Polyclonal Antibody; Clontech) or 50 µL GFP-trap beads (GFP-Trap A; Chromotek) on a rolling platform at 4 °C overnight. The precipitations were washed four times in 500 µL TBST lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with 5× SDS loading buffer (5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 45% glycerol, 5% SDS, 0.1% Pyronin Y, and 3.5% β-mercaptoethanol). Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and complete lanes were excised for MS analysis.

Each lane of the SDS/PAGE gel was sliced and fragmented into small 1-mm3 pieces. These gel slices were destained two times with 200 µL 50% acetonitrile (ACN) and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) at 37 °C for 30 min and then dehydrated with 100% ACN. Solvent was removed in a vacuum centrifuge, and 20 µL of 6 ng/µL sequencing grade Trypsin (Serva) in 10% ACN and 40 mM ABC was added. Gels were rehydrated in trypsin solution for 1 h on ice and then covered with 10% ACN and 40 mM ABC. Digestion was performed overnight at 37 °C. Digestion was stopped, and peptides were extracted by adding 100 µL 50% ACN and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. This step was repeated twice, and extracts were combined and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Dried peptide extracts were redissolved in 30 µL 2% ACN and 0.1% TFA by soft shaking for 20 min and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g, and the supernatant was stored as aliquots of 12.5 µL at −20 °C.

A sample aliquot was injected into a nano-flow ultra-HPLC system (RSLC; Dionex) equipped with a trapping column (5-µm C18 particle, 2-cm length, 75-µm ID, PepMap; Dionex) and a separating column (2-µm C18 particle, 50-cm length, 75-µm ID, PepMap; Dionex). The outlet of the RSLC system was directly connected to the nano-ESI source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) of the Orbitrap mass spectrometer. A voltage of 1.2 kV was applied at the ESI source, and ionized peptides were analyzed in a LTQ-Orbitrap velos mass spectrometer. Overview scans were acquired at a resolution of 60,000 in a mass range of m/z 300–1,600 in the orbitrap. The top 10 most intensive ions of charge 2 or 3, a minimum intensity of 2,000, and an isolation width of 2 Th (a unit of mass-to-charge ratio) were selected for CID (collision-induced dissociation) fragmentation with a normalized collision energy of 38.0, an activation time of 10 ms, and an activation Q (parameter for Orbitrap mass spectrometry) of 0.250 in the LTQ (linear trap quadrupole) part of the LTQ Orbitrap velos mass spectrometer. The m/z values in a 10-ppm mass window of the selected ions were subsequently excluded from the fragmentation for 70 s.

Raw data were processed with the Proteome discoverer software package version 1.2 (Thermo Fisher) for identification of proteins using Mascot and the human entries of the Uniprot/Swissprot database. Proteins were stated identified if at least two peptides per protein were identified with a peptide ion score greater than 30 and a false discovery rate of less than 0.05.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Antibody-conjugated beads were prepared as follows: 20 µL anti-LANA antibody (13-210-100; Advanced Biotechnologies; 1 mg/mL) or 40 µL IgG (GTX35063; Genetex; 0.5 mg/mL) was incubated on ice for 15 min with 45 µL PBS containing 4% sucrose and 0.02% sodium azide. Eighty microliters of protein A beads (17-5280-01; GE Healthcare) were washed three times in TBST lysis buffer and incubated with the anti-LANA antibody overnight at 4 °C on a rolling platform. Before use, the antibody-conjugated beads were washed three times with 500 µL TBST lysis buffer.

BCBL-1 cells were suspended in TBST lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (1.5 mM aprotinin, 10 mM leupeptin, 100 mM PMSF, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1.46 mM pepstatin A) on ice and treated with 200 U/mL benzonase. After centrifugation, the lysates were precleared with protein A beads for 2 h at 4 °C. The lysates were divided into two equal parts and incubated with 15 µL anti-LANA conjugated beads or control antibody conjugated beads overnight at 4 °C on a rolling platform. The beads were pelleted and washed six times with TBST buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with 5× SDS loading buffer and separated by SDS/PAGE.

Co-IP of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from BCBL-1 cells was performed as follows: after centrifugation for 5 min at 900 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5810 R, rotor A-4-81, Hamburg, Germany), 50 µL pelleted BCBL-1 cells were fractionated according to the protocol of NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (78833; Thermo Scientific). For IP, 500 µL cytoplasmic extract was mixed with cold 500 µL lysis buffer, and 250 µL nuclear extract was mixed with 250 µL lysis buffer. Both cytoplasmic extract and nuclear extract were precleared with 40 µL protein A beads for 2 h at 4 °C on a rolling platform, each was divided into two equal parts, and each part was incubated with 15 µL anti-LANA antibody-conjugated beads or IgG control beads.

Transfection of siRNA by Electroporation.

HuAR2T.rKSHV.219 cells (1 × 105) were electroporated with 100 pmol of siRNA using the Neon Transfection System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (pulse voltage: 1,350 V; pulse width: 30 ms; pulse number 1; tip type, 10 µL), and seeded in a 12-well plate. The siRNAs were obtained from Dharmacon and Thermo Scientific (cGAS siRNA MQ-015607–01-0002, STING siRNA M-024333–00-0010, nontargeting control siRNA d-001206-14-50).

HSV-1 Infection and Plaque Assay.

HSV-1(17+)Lox-pMCMVmCherry (kindly provided by B. Sodeik, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany) was propagated using BHK-21 cells and purified as previously described (74). The titer was determined by plaque assays, and the genome to plaque-forming units (PFU) ratio was determined by real-time PCR (74).

HeLa MZ, HeLa MZ-LANA FL, or HeLa MZ-LANAΔ161 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 0.5 × 104 cells per well. Before infection with HSV-1, the medium was changed, and the cells were incubated with 50 µL/well of CO2-independent medium (Life Technologies Gibco) supplemented with 0.1% BSA on ice for 20 min. Subsequently, HSV-1 suspension was added, and the cells were incubated for 60 min on ice on a slow rocking platform to allow virus attachment. After washing three times with 50 µL CO2-independent medium (with 0.1% BSA), 100 µL fresh DMEM was added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

The plaque titration was performed as previously described (75). Briefly, Vero cells were seeded in six-well plates for 16–20 h before virus inoculation. After washing the cells with PBS, 500 µL CO2-independent medium (with 0.1% BSA) was added to each well. Then, the supernatant containing HSV-1 virions produced by HeLa MZ cells (24 and 36 h after infection) was added, and cells were incubated on a slow rocking platform at room temperature for 60 min. After removal of the virus, 2 mL fresh DMEM containing 40 µg/mL IgG solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C. Three days later, the medium was removed, and the cells were fixed with 1 mL/well of prechilled (−20 °C) methanol. After removal of the methanol and drying of the samples, the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and 2% EtOH. The plaques were counted after removal of the staining solution.

Luciferase Reporter Assay.

HeLa MZ, HeLa MZ-LANA, or HeLa MZ-LANAΔ161 cells (4 × 104) were seeded per well of a 12-well plate in triplicate and transfected with 0.5 µg IFN-β promoter reporter construct using 1.5 µL Lipofectamine 2000 without further DNA stimulation. Four hours after transfection, the medium was changed. The cells were lysed in 100 µL 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega) 24 h after transfection, and 20 µL cell lysate was used for luciferase activity measurement using a luminometer.

2′3′cGAMP Quantification by HPLC/MS.

HeLa MZ cells (8 × 104) stably expressing LANA-FL or LANAΔ161 were seeded in six-well plates and transfected with 4 µg ISD complexed with 4 µL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

The cells in each well were resuspended in 500 µL X-100 buffer (1 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 mM Trip, pH 7.4) after one cold PBS wash and kept on ice for 20 min. The cells were spun down at 1,000 × g at 4 °C after regular vortexing. The supernatant was collected and incubated with 50 U/mL benzonase for 45 min on ice. The upper aqueous layer was collected after adding 500 µL P:I:C (phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol: 25:24:1; Sigma), vortexed vigorously, and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D, rotor FA-45-24-11, Hamburg, Germany), which was repeated once. The collected aqueous layer was added to 500 µL chloroform, vortexed vigorously, and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D, rotor FA-45-24-11, Hamburg, Germany). The upper aqueous layer was poured into an Amicon 3K filter column (Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit with Ultracel-3 membrane; Millipore) and centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 × g. The pellets were resuspended in 20 µL H2O after centrifuge in a SpeedVac Concentrator.

The method for detection and quantification of 2′3′cGAMP has been described in ref. 76. Calibrators or sample extracts separation by reversed-phase chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed using an HPLC system (Shimadzu). The mobile phases were 3/97 methanol/water (vol/vol) (A) and 97/3 methanol/water (vol/vol) (B), both contain 50 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% acetic acid. The following gradient was applied: 0–5 min, 0–50% B, and 5–8 min, 0% B, with a flow rate of 500 μL/min. 2′3′cGAMP was detected and quantified by a tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) 5500QTRAP (AB Sciex), and the following mass transitions [M+H]+ were identified for 2′3′-cGAMP: m/z 675.0 → 136.2 (quantifier), m/z 675.0 → 152.1 (identifier) and for tenofovir: m/z 288.0 → 176.0 (quantifier), m/z 288.0 → 159.1 (identifier).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with the GraphPad Prism 5 software. All datasets were analyzed using t tests (unpaired t test, two-tailed). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. S. Moore for kindly providing expression plasmids and anti-LANA antibody, and Dr. K. M. Kaye and Dr. A. Ablasser for generously providing expression plasmids. We thank Dr. B. Sodeik (Hannover Medical School) for kindly providing HSV-1 virus stock. We thank the Core Facilities Cell Sorting (Dr. M. Ballmaier) and Metabolomics (Dr. V. Kaever) of the Hannover Medical School for assistance. This study was supported by grants to T.F.S. and M.M.B. of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [Collaborative Research Centre SFB900 “Chronic Infections: Microbial Persistence and its Control,” Project C1 (to T.F.S.) and Project B3 (to M.M.B.)]. G.Z. is a scholarship holder of China Scholarship Council (2011621026) and supported by the Infection Biology international PhD program of Hannover Biomedical Research School. B.C. and M.M.B. were funded by the Helmholtz Association through the Helmholtz Virtual Institute “Viral Strategies of Immune Evasion” (VH VI-424). A.B. was supported by the Niedersachsen-Research Network on Neuroinfectiology of the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, Germany.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1516812113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kedes DH, et al. The seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus): Distribution of infection in KS risk groups and evidence for sexual transmission. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):918–924. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao SJ, et al. KSHV antibodies among Americans, Italians and Ugandans with and without Kaposi’s sarcoma. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):925–928. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao SJ, et al. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(4):233–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607253350403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rainbow L, et al. The 222- to 234-kilodalton latent nuclear protein (LNA) of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) is encoded by orf73 and is a component of the latency-associated nuclear antigen. J Virol. 1997;71(8):5915–5921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5915-5921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kedes DH, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Ganem D. Identification of the gene encoding the major latency-associated nuclear antigen of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(10):2606–2610. doi: 10.1172/JCI119804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbera AJ, et al. The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus LANA. Science. 2006;311(5762):856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1120541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbera AJ, Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 N terminus is essential for chromosome association, DNA replication, and episome persistence. J Virol. 2004;78(1):294–301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.294-301.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan K, Kuppers DA, Verma SC, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits lytic replication by targeting Rta: A potential mechanism for virus-mediated control of latency. J Virol. 2004;78(12):6585–6594. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6585-6594.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. The latency-associated nuclear antigen, a multifunctional protein central to Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(12):1399–1413. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garber AC, Hu J, Renne R. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) cooperatively binds to two sites within the terminal repeat, and both sites contribute to the ability of LANA to suppress transcription and to facilitate DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):27401–27411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An FQ, et al. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus modulates cellular gene expression and protects lymphoid cells from p16 INK4A-induced cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(5):3862–3874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang D, et al. Oncogenic herpesvirus KSHV hijacks BMP-Smad1-Id signaling to promote tumorigenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(7):e1004253. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Bartolo DL, et al. KSHV LANA inhibits TGF-beta signaling through epigenetic silencing of the TGF-beta type II receptor. Blood. 2008;111(9):4731–4740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe T, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen prolongs the life span of primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Virol. 2003;77(11):6188–6196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6188-6196.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cloutier N, Flamand L. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits interferon (IFN) beta expression by competing with IFN regulatory factor-3 for binding to IFNB promoter. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7208–7221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HR, Brulois K, Wong L, Jung JU. Modulation of immune system by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: Lessons from viral evasion strategies. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:44. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun C, et al. Evasion of innate cytosolic DNA sensing by a gammaherpesvirus facilitates establishment of latent infection. J Immunol. 2015;194(4):1819–1831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Full F, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus tegument protein ORF75 is essential for viral lytic replication and plays a critical role in the antagonization of ND10-instituted intrinsic immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(1):e1003863. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bussey KA, et al. The gammaherpesviruses Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 modulate the Toll-like receptor-induced proinflammatory cytokine response. J Virol. 2014;88(16):9245–9259. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00841-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inn KS, et al. Inhibition of RIG-I-mediated signaling by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded deubiquitinase ORF64. J Virol. 2011;85(20):10899–10904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00690-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Z, et al. Modulation of the cGAS-STING DNA sensing pathway by gammaherpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(31):E4306–E4315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503831112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu JJ, et al. Inhibition of cGAS DNA sensing by a herpesvirus virion protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18(3):333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau L, Gray EE, Brunette RL, Stetson DB. DNA tumor virus oncogenes antagonize the cGAS-STING DNA-sensing pathway. Science. 2015;350(6260):568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis DA, et al. Identification of caspase cleavage sites in KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen and their effects on caspase-related host defense responses. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(7):e1005064. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwun HJ, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mimics Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 immune evasion through central repeat domain effects on protein processing. J Virol. 2007;81(15):8225–8235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00411-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwun HJ, et al. The central repeat domain 1 of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) latency associated-nuclear antigen 1 (LANA1) prevents cis MHC class I peptide presentation. Virology. 2011;412(2):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai Q, et al. IRF-4-mediated CIITA transcription is blocked by KSHV encoded LANA to inhibit MHC II presentation. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(10):e1003751. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thakker S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits major histocompatibility complex class II expression by disrupting enhanceosome assembly through binding with the regulatory factor X complex. J Virol. 2015;89(10):5536–5556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03713-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekerman E, Jeon D, Ardolino M, Coscoy L. A role for host activation-induced cytidine deaminase in innate immune defense against KSHV. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(11):e1003748. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platt GM, Simpson GR, Mittnacht S, Schulz TF. Latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with RING3, a homolog of the Drosophila female sterile homeotic (fsh) gene. J Virol. 1999;73(12):9789–9795. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9789-9795.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viejo-Borbolla A, et al. Brd2/RING3 interacts with a chromatin-binding domain in the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 (LANA-1) that is required for multiple functions of LANA-1. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13618–13629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13618-13629.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohsaki E, Ueda K. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome replication, partitioning, and maintenance in latency. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krithivas A, Fujimuro M, Weidner M, Young DB, Hayward SD. Protein interactions targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to cell chromosomes. J Virol. 2002;76(22):11596–11604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11596-11604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumura S, Persson LM, Wong L, Wilson AC. The latency-associated nuclear antigen interacts with MeCP2 and nucleosomes through separate domains. J Virol. 2010;84(5):2318–2330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01097-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toptan T, Fonseca L, Kwun HJ, Chang Y, Moore PS. Complex alternative cytoplasmic protein isoforms of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 generated through noncanonical translation initiation. J Virol. 2013;87(5):2744–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339(6121):786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ablasser A, et al. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498(7454):380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP containing mixed phosphodiester linkages is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for STING. Mol Cell. 2013;51(2):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao P, et al. Cyclic [G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] is the metazoan second messenger produced by DNA-activated cyclic GMP-AMP synthase. Cell. 2013;153(5):1094–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diner EJ, et al. The innate immune DNA sensor cGAS produces a noncanonical cyclic dinucleotide that activates human STING. Cell Reports. 2013;3(5):1355–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mankan AK, et al. Cytosolic RNA:DNA hybrids activate the cGAS-STING axis. EMBO J. 2014;33(24):2937–2946. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoggins JW, et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature. 2014;505(7485):691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XD, et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science. 2013;341(6152):1390–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1244040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russo JJ, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(25):14862–14867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu J, Garber AC, Renne R. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus supports latent DNA replication in dividing cells. J Virol. 2002;76(22):11677–11687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11677-11687.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hellert J, et al. The 3D structure of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus LANA C-terminal domain bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(21):6694–6699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421804112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alkharsah KR, Schulz TF. A role for the internal repeat of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent nuclear antigen in the persistence of an episomal viral genome. J Virol. 2012;86(3):1883–1887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06029-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De León Vázquez E, Kaye KM. The internal Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA regions exert a critical role on episome persistence. J Virol. 2011;85(15):7622–7633. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00304-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vázquez EdeL, Carey VJ, Kaye KM. Identification of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA regions important for episome segregation, replication, and persistence. J Virol. 2013;87(22):12270–12283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01243-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murakami Y, et al. Ets-1-dependent expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors is activated by latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus through interaction with Daxx. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(38):28113–28121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haas DA, et al. The inflammatory kinase MAP4K4 promotes reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus and enhances the invasiveness of infected endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(11):e1003737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vieira J, O’Hearn PM. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology. 2004;325(2):225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Q, Zhou F, Ye F, Gao SJ. Genetic disruption of KSHV major latent nuclear antigen LANA enhances viral lytic transcriptional program. Virology. 2008;379(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kati S, et al. Activation of the B cell antigen receptor triggers reactivation of latent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in B cells. J Virol. 2013;87(14):8004–8016. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kati S, et al. Generation of high-titre virus stocks using BrK.219, a B-cell line infected stably with recombinant Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol Methods. 2015;217:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwun HJ, et al. Human DNA tumor viruses generate alternative reading frame proteins through repeat sequence recoding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(41):E4342–E4349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416122111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsumura S, Fujita Y, Gomez E, Tanese N, Wilson AC. Activation of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus major latency locus by the lytic switch protein RTA (ORF50) J Virol. 2005;79(13):8493–8505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8493-8505.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearce M, Matsumura S, Wilson AC. Transcripts encoding K12, v-FLIP, v-cyclin, and the microRNA cluster of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus originate from a common promoter. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14457–14464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14457-14464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steed A, Buch T, Waisman A, Virgin HW., 4th Gamma interferon blocks gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latency in a cell type-specific manner. J Virol. 2007;81(11):6134–6140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00108-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steed AL, et al. Gamma interferon blocks gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latency. J Virol. 2006;80(1):192–200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.192-200.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barton ES, Lutzke ML, Rochford R, Virgin HW., 4th Alpha/beta interferons regulate murine gammaherpesvirus latent gene expression and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14149–14160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14149-14160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Regge N, Van Opdenbosch N, Nauwynck HJ, Efstathiou S, Favoreel HW. Interferon alpha induces establishment of alphaherpesvirus latency in sensory neurons in vitro. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e13076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dağ F, et al. Reversible silencing of cytomegalovirus genomes by type I interferon governs virus latency. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(2):e1003962. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson EB, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science. 2013;340(6129):202–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1235208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]