Significance

Endothelial cell migration is required for vessel repair after damage during angioplasty. Migration is inhibited by lipid oxidation products, including lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC), that are abundant in atherosclerotic plaques. Inhibition of migration is dependent on Ca2+ entering through canonical transient receptor potential 6 (TRPC6) channels externalized by lysoPC's action. Here we uncover an unappreciated role for activation of PI3K by calmodulin (CaM) requiring phosphorylation of its Tyr99. Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) formed by PI3K facilitates insertion of endocellular TRPC6 channels into the plasma membrane. The CaM-PI3K signaling mechanism may also operate in externalization of additional TRPC channels and for other membrane functions residing primarily on endomembranes prior to stimulation by extracellular signals, including glucose transporter 4 in response to insulin, and aquaporin-2 in response to vasopressin.

Keywords: endothelial, calmodulin, PI3 kinase, TRPC6

Abstract

Lipid oxidation products, including lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC), activate canonical transient receptor potential 6 (TRPC6) channels leading to inhibition of endothelial cell (EC) migration in vitro and delayed EC healing of arterial injuries in vivo. The precise mechanism through which lysoPC activates TRPC6 channels is not known, but calmodulin (CaM) contributes to the regulation of TRPC channels. Using site-directed mutagenesis, cDNAs were generated in which Tyr99 or Tyr138 of CaM was replaced with Phe, generating mutant CaM, Phe99-CaM, or Phe138-CaM, respectively. In ECs transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe99-CaM, but not in ECs transfected with pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe138-CaM, the lysoPC-induced TRPC6-CaM dissociation and TRPC6 externalization was disrupted. Also, the lysoPC-induced increase in intracellular calcium concentration was inhibited in ECs transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe99-CaM. Blocking phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 also reduced CaM association with the p85 subunit and subsequent activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). This prevented the increase in phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) and the translocation of TRPC6 to the cell membrane and reduced the inhibition of EC migration by lysoPC. These findings suggest that lysoPC induces CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 by a Src family kinase and that phosphorylated CaM activates PI3K to produce PIP3, which promotes TRPC6 translocation to the cell membrane.

Endothelial cell (EC) migration is required for healing after arterial injuries, such as those that occur with angioplasties. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC), the major lysophospholipid of oxidized low-density lipoprotein, are abundant in plasma and atherosclerotic lesions and inhibit EC migration (1). A brief influx of calcium is required to initiate EC migration (2), but lysoPC causes a prolonged influx of Ca2+ that disrupts the cytoskeletal dynamics required for normal EC migration (3, 4). Specifically, lysoPC activates canonical transient receptor potential 6 (TRPC6) channels, as shown by patch clamp recording, with Ca2+ influx (3). The increased [Ca2+]i initiates events that result in TRPC5 channel activation (3). The later activation of TRPC5 compared with TRPC6 and the failure of TRPC6 and TRPC5 to coimmunoprecipitate indicates that they do not form a heteromeric complex. The importance of this pathway is found in TRPC6-deficient EC, where lysoPC has little effect on EC migration (3). Furthermore, a high cholesterol diet markedly inhibits endothelial healing in wild-type (WT) mice, but has no effect in TRPC6-deficient (TRPC6−/−) mice (5). The mechanism of TRPC6 activation by lysoPC is not fully elucidated, limiting the ability to block this important pathway.

Calmodulin (CaM), a small, highly conserved, intracellular calcium-binding protein (6), binds to TRPC channels and regulates their activation. TRPC proteins, including TRPC6, possess a C-terminal CaM-binding domain that overlaps with a binding site for the inositol trisphosphate receptor, and CaM and the inositol triphosphate receptor compete for binding at this site (7). Removal of CaM from the common binding site results in activation of TRP3 channels (8). TRPC proteins contain additional binding sites for CaM and other Ca2+-binding proteins, indicating a complex regulatory mechanism in response to changes in [Ca2+]i that includes positive and negative regulation of channels (9). In addition to CaM regulating TRPC proteins by direct binding, CaM-dependent kinases activate TRPC channels (10). CaM activity and peptide binding affinity is altered by its phosphorylation state and bound Ca2+, and Ca2+ can regulate the phosphorylation of CaM (11). LysoPC activates tyrosine kinases, including Src family tyrosine kinases (12), and Src family kinases can phosphorylate CaM (13). The role of CaM and CaM phosphorylation in TRPC6 channel activation or in EC migration is incompletely understood.

TRPC6 channel activation generally requires externalization; however, the mechanism of TRPC6 channel translocation to the plasma membrane is not clear. In HEK cells overexpressing TRPC6, stimulation of Gq protein-coupled receptors causes TRPC6 externalization and localization to caveolae or lipid rafts by an exocytotic mechanism (14). In smooth muscle cells, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) is involved in carbachol-induced TRPC6 externalization (15). The mechanism by which lysoPC induces TRPC6 externalization in EC is unknown.

PI3K produces phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) from phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and participates in numerous intracellular signaling processes, including TRPC6 activation (16). PI3K is composed of a p85 regulatory subunit (p85α, p85β, or p55γ) and a p110 catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, p110γ, or p110δ), and activity can be influenced by CaM association (17).

The purpose of the present study is to explore the underlying mechanism of lysoPC-induced TRPC6 activation. We identify a mechanism in which phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 plays a key role in lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization and inhibition of EC migration.

Results

LysoPC Induces Dissociation of CaM from TRPC6 and CaM-Mediated TRPC6 Externalization.

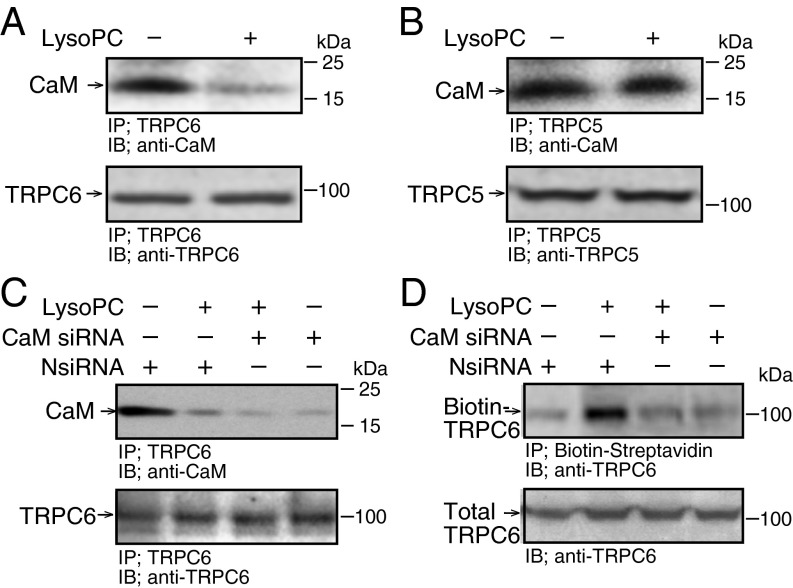

LysoPC (1-palmitol-2-hydroxy-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine; Avanti Polar Lipids) caused significant but not complete dissociation of CaM from TRPC6 (n = 4, P < 0.01 compared with control, Fig. 1A). Interestingly, lysoPC caused no dissociation of CaM from TRPC5 (n = 4, Fig. 1B), showing that changes were specific for TRPC6 and not due to CaM degradation.

Fig. 1.

LysoPC induces TRPC6-CaM dissociation but down-regulation of CaM reduces TRPC6 externalization. (A and B) BAECs were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. TRPC6 or TRPC5 was immunoprecipitated and associated CaM identified by immunoblot analysis. In aliquots removed after immunoprecipitation, total TRPC6 or TRPC5 was determined (n = 4). (C and D) BAECs were transiently transfected with negative control siRNA (NsiRNA) or CaM siRNA (20 nM) for 24 h, then incubated with lysoPC. TRPC6-CaM association was identified as above (n = 3) or TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay (n = 4).

Transient transfection of bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) with CaM small interfering RNA (siRNA) decreased CaM expression to 20 ± 3% of control (Fig. S1) and decreased CaM-TRPC6 association to 20 ± 2% of that in BAECs transfected with negative control siRNA (NsiRNA) under control conditions and to 7 ± 2% of that in BAECs transfected with NsiRNA after incubation with lysoPC (n = 3, P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). Importantly, when CaM was down-regulated, lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization was significantly inhibited (n = 4, P < 0.01 compared with NsiRNA; Fig. 1D). These findings suggested that CaM was necessary for lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization, and that simply decreasing CaM association with TRPC6 did not promote TRPC6 externalization.

Fig. S1.

CaM siRNA decreases CaM protein level. BAECs were transiently transfected with control siRNA (NsiRNA) or CaM siRNA (20 nM) for 24 h. After 48 h CaM was identified by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 3). Transient transfection of BAECs with CaM small interfering RNA (siRNA), decreased CaM expression to 20 ± 3% of control (n = 3, P < 0.01).

LysoPC Induces Phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 by a Src Family Kinase That Is Dependent on Ca2+ but Independent of TRPC6.

The effect of lysoPC on CaM phosphorylation was assessed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for CaM phosphorylated at Tyr99, Tyr138, or Ser81 and Thr79. In BAECs incubated with lysoPC, CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 was increased 2.1 ± 0.4-fold compared with control (n = 5, P < 0.01; Fig. 2A), but CaM phosphorylation at Tyr138 was unchanged (n = 3, Fig. 2B). Epidermal growth factor (100 nM), known to induce Tyr138 phosphorylation, was the positive control. LysoPC did not increase CaM phosphorylation at Ser81 or Thr79 (n = 4, Fig. 2C). Pretreatment of BAECs with a Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PP2 (2 µM), blocked lysoPC-induced CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 (Fig. S2A), inhibited lysoPC-induced CaM dissociation from TRPC6 (Fig. S2B) and TRPC6 externalization (Fig. S2C), and preserved BAEC migration in lysoPC (Fig. S2D). These results suggested that lysoPC induced CaM phosphorylation specifically at Tyr99 by activation of a Src family kinase.

Fig. 2.

LysoPC induces CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99, which is Ca2+ dependent, but not CaM phosphorylation at Tyr138, Ser81, or Thr79. (A–F) BAECs were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. (A–C) Phospho-CaM was identified by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control. (A) Phospho-CaM(Tyr99) was identified (n = 5). (B) Phospho-CaM(Tyr138) was identified (n = 3). Epidermal growth factor (EGF, 100 nM) for 30 min served as a positive control. (C) Phospho-CaM(Ser81/Thr79) was identified (n = 4). (D) BAECs preincubated with BAPTA/AM (25 µM) for 30 min before adding lysoPC. Phospho-CaM(Tyr99) was detected by immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (Lines indicate lanes rearranged from same gel.) (E and F) BAECs were incubated with BAPTA/AM (300 µM) for 30 min before adding lysoPC. (E) Phospho-CaM was detected by immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (F) TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay (n = 3).

Fig. S2.

Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PP2, blocks lysoPC-induced CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99, CaM dissociation from TRPC6, TRPC6 externalization, and preserved EC migration. BAECs were pretreated with PP2 (2 µM) for 1 h before incubation with lysoPC (12.5 µM). (A) Phospho-CaM(Tyr99) was identified by immunoblot analysis (n = 4). LysoPC-induced CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 was inhibited (n = 4, P < 0.01 compared with no pretreatment). Actin served as loading control (n = 4). (B) TRPC6 was immunoprecipitated and associated CaM identified by immunoblot analysis. In aliquots removed after immunoprecipitation, total TRPC6 was determined (n = 4, P < 0.01 compared with no pretreatment). (Lines indicate lanes rearranged from same gel.) (C) TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay. Total TRPC6 was assessed by immunoblot analysis in aliquots removed before incubation with streptavidin-agarose beads (n = 3). (D) Migration was assessed after 24 h in the presence or absence of lysoPC (12.5 µM) and results are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.001 compared with control and **P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC).

CaM interactions with its target proteins are regulated by Ca2+ loading as well as phosphorylation (13). TRPC6 activation can be regulated by Ca2+ (10). To assess the role of Ca2+ in the lysoPC-induced phosphorylation of CaM and subsequent TRPC6 activation, BAECs were incubated with BAPTA/AM (25 µM or 300 µM). After 30 min, lysoPC (12.5 µM) was added for 15 min in the presence of Ca2+-containing Krebs-Ringer (KR) buffer. In BAECs preincubated in BAPTA/AM (25 µM), lysoPC induced CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 (n = 3, Fig. 2D), but in BAECs preincubated in BAPTA/AM (300 µM), lysoPC did not induce CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 (n = 3, Fig. 2E). Similarly, lysoPC did not induce TRPC6 externalization in BAECs preincubated with 300 µM of BAPTA/AM (n = 3, Fig. 2F). These results suggested that a local increase of Ca2+ is essential for lysoPC-induced CaM phosphorylation and subsequent TRPC6 externalization.

To assess the role of TRPC6 in lysoPC-induced CaM phosphorylation, TRPC6−/− mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) were studied. Incubation with lysoPC (10 µM) induced CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 in TRPC6−/− MAECs as well as in WT MAECs (n = 3, Fig. S3), suggesting that CaM phosphorylation was independent of TRPC6.

Fig. S3.

LysoPC induces similar levels of CaM phosphorylation of CaM in WT and TRPC6−/− MAECs. WT or TRPC6−/− MAECs were incubated with lysoPC (10 µM for 15 min) and phospho-CaM(Tyr99) was detected by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 3).

CaM Phosphorylation at Tyr99 Is Required for LysoPC-Induced TRPC6 Externalization.

To evaluate the role of CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 in TRPC6 externalization, mutant CaMs were generated, in which Tyr was replaced with Phe, which cannot be phosphorylated. BAECs were transiently transfected with plasmids containing the vector pcDNA 3.1-myc-His with or without cDNA for WT-CaM, Phe99-CaM, or Phe138-CaM for 24 h, and overexpression was confirmed after 48 h by immunoblot analysis (n = 3, Fig. S4 A and B). LysoPC increased CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM (P < 0.01), but not in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 4, Fig. S4C). In another approach, Tyr99 was replaced by Asp, which would behave as a constitutively phosphorylated CaM, but BAECs transiently transfected with this mutant were not viable.

Fig. S4.

Expression of mutant CaM. (A–C) BAECs were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-myc-His-WT-CaM or pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe138-CaM for 24 h. (A and B) Overexpression was confirmed after 48 h by immunoblot analysis with anti-Myc Tag antibody. Actin served as loading control (n = 3). (C) At 24 h, BAECs were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. Phospho-CaM(Tyr99) was detected by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 4). LysoPC increased CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 1.82 ± 0.2-fold over control in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM (P < 0.01), but not in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 4). (D and E) Human endothelial cells (EA.hy926) were transiently transfected for 24 h with cDNA for WT-CaM or Phe99-CaM. (D) After 48 h, overexpression was verified by immunoblot analysis using anti-Myc tag antibody, and actin served as the loading control (n = 3). (E) Ea.hy926 cells were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay and total TRPC6, by immunoblot analysis in aliquots removed before incubation with streptavidin-agarose beads (n = 3).

In BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM, lysoPC induced: (i) CaM dissociation from TRPC6 (7.8 ± 0.3-fold decrease compared with control, P < 0.01, n = 4; Fig. 3A), (ii) TRPC6 tyrosine phosphorylation (2.8 ± 0.3-fold increase compared with control, P < 0.01, n = 4; Fig. 3B), and (iii) TRPC6 externalization (2.6 ± 0.5-fold increase over control, P < 0.01, n = 4; Fig. 3C). These events did not occur in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM, suggesting that Tyr99 phosphorylation was required. The finding was not unique to BAECs. In human ECs (EA.hy 926), phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 was required for TRPC6 externalization (Fig. S4 D and E).

Fig. 3.

In BAECs expressing CaM mutated at Tyr99, lysoPC fails to induce TRPC6-CaM dissociation, TRPC6 tyrosine phosphorylation, and TRPC6 externalization. (A–D) BAECs were transiently transfected for 24 h with pcDNA3.1-myc-His-WT-CaM, pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe99-CaM, or pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe138-CaM. At 24 h, BAECs were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. (A) Myc-conjugated CaM was immunoprecipitated and associated TRPC6 was detected by immunoblot analysis (n = 4). (Lines indicate lanes rearranged from same gel.) (B) TRPC6 was immunoprecipitated, then immunoblot analysis using antiphosphotyrosine or anti-TRPC6 antibody identified tyrosine-phosphorylated TRPC6 or total TRPC6 (n = 4). (C and D) TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay (n = 4).

To confirm the specificity of CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 for TRPC6 externalization, BAECs overexpressing Phe138-CaM, in which Tyr138 was replaced with Phe, were studied. LysoPC induced TRPC6 externalization in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM or Phe138-CaM with a 2.6 ± 0.5-fold or 2.6 ± 0.3-fold increases, respectively, compared with control (n = 3, P < 0.01; Fig. 3D), suggesting that CaM phosphorylation at Tyr138 was not required.

CaM Phosphorylation at Tyr99 Is Required for LysoPC-Induced TRPC6-Dependent Increase in [Ca2+]i.

BAECs were transiently transfected with a plasmid containing cDNA for the empty vector or the vector with WT-CaM, Phe99-CaM, or TRPC6. Other BAECs were transfected with a combination of two plasmids. Overexpression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis at 24 h (Fig. S5 A and B). The lysoPC-induced rise in [Ca2+]i was similar in BAECs transfected with empty vector or WT-CaM (n = 8, Fig. 4 A and B), but Phe99-CaM significantly decreased the lysoPC-induced rise in [Ca2+]i to 52.3 ± 2.4% of that seen with WT-CaM overexpression (n = 8, P < 0.001 compared with WT-CaM, Fig. 4 B and C). The lysoPC-induced rise in [Ca2+]i was increased by 33.2 ± 4.0% in BAECs overexpressing TRPC6 (n = 8, P < 0.001, compared with empty vector, Fig. 4 A and D), supporting a role for TRPC6 in the rise of [Ca2+]i. Similarly, a 33.3 ± 5.2% increase in peak [Ca2+]i was observed in BAECs overexpressing TRPC6 and WT-CaM (n = 8, Fig. 4E). The peak in [Ca2+]i was significantly less in BAECs overexpressing TRPC6 and Phe99-CaM, only 40.6 ± 1.8% of that seen in BAECs overexpressing TRPC6 and WT-CaM (n = 8, P < 0.001; Fig. 4 E and F). These results, summarized graphically in Fig. 4G, suggest that CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 is critical for lysoPC-induced TRPC6-mediated increase of [Ca2+]i.

Fig. S5.

Expression of mutant CaM and TRPC6. (A and B) BAECs were transiently transfected with a plasmid containing empty vector or vector with WT-CaM, Phe99-CaM, or TRPC6 or a combination of plasmids for 16 h. After 24 h, immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc tag antibody (A, n = 3) or anti-TRPC6 antibody (B, n = 3). Actin served as loading control.

Fig. 4.

In BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM, lysoPC does not increase [Ca2+]i. (A–F) BAECs were transiently transfected with a plasmid containing empty vector or vector with WT-CaM, Phe99-CaM, or TRPC6, or a combination of plasmids as indicated for 16 h, made quiescent for 8 h, then loaded with fura 2-AM. After adjusting the baseline, lysoPC (12.5 µM) was added (arrow) and relative change of [Ca2+]i measured. A representative tracing of n = 8 cells is shown. (G) The mean ± SD of [Ca2+]i changes are depicted in graphic form (n = 8 measurements per condition). The change in [Ca2+]i was calculated as peak fluorescence ratio minus baseline ratio divided by baseline ratio (*P < 0.001 compared with overexpression of WT-CaM, †P < 0.002 compared with vector, **P < 0.001 compared with overexpression of TRPC6 and WT-CaM).

CaM-Dependent PI3K Activation Induces TRPC6 Externalization.

The above studies suggested that CaM phosphorylated at Tyr99 activated a mechanism responsible for TRPC6 externalization. CaM kinase II was reported to be involved in TRPC6 activation in HEK cells overexpressing TRPC6 (10), and CaM kinase II is expressed in ECs. Pretreatment of BAECs for 1 h with a specific, cell-permeable, CaM kinase II inhibitor, autocamtide-2-related inhibitory peptide (10 µM, Millipore), did not alter lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization (n = 4, Fig. S6A).

Fig. S6.

Inhibition of CaM kinase II or Pyk2 do not block lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization. (A) BAECs were pretreated with a CaM kinase II inhibitor, autocamtide 2-related inhibitory peptide (AIP, 10 µM) for 1 h before incubation with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay and total TRPC6 by immunoblot analysis (n = 4). (B and C) BAECs were transiently transfected with control siRNA (NsiRNA) or Pyk2 siRNA (20 nM) for 24 h. (B) After 48 h, Pyk2 was identified by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 3). (C) After incubation with lysoPC, TRPC6 externalization was detected by biotinylation assay and total TRPC6, by immunoblot analysis (n = 3).

The role of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2), a tyrosine kinase that is activated by lysoPC (18), interacts with CaM (19), and regulates ion channel function (20), was assessed. In BAECs transiently transfected with Pyk2 siRNA for 24 h, immunoblot analysis at 48 h confirmed down-regulation of Pyk2 (n = 3, Fig. S6B). LysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization, however, was not altered by Pyk2 down-regulation (n = 3, Fig. S6C).

PI3K is involved in carbachol-induced TRPC6 externalization in smooth muscle cells (15), and PI3K activity is enhanced by CaM association with the p85 subunit of PI3K (17). To assess the role of PI3K, BAECs were transiently transfected with p110α siRNA or p85α siRNA for 24 h. Immunoblot analysis after 48 h confirmed down-regulation of p110α or p85α to 18 ± 2% or 12 ± 2% of basal level, respectively (n = 3, P < 0.04 compared with NsiRNA; Fig. S7 A and B). LysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization was blocked by down-regulation of p110α or p85α (n = 4, P < 0.02, compared with NsiRNA transfected BAECs; Fig. 5 A and B), but total endogenous TRPC6 level was not altered. These findings supported a role for lysoPC-induced PI3K activation in TRPC6 externalization. Pretreating BAECs with a PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (20 µM), for 1 h before incubation with lysoPC (12.5 µM) also blocked lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization (n = 4, P < 0.02 compared with lysoPC alone; Fig. 5C), but did not alter lysoPC-induced CaM dissociation from TRPC6 (n = 3, Fig. 5D).

Fig. S7.

The p110α or p85α subunit of PI3K is effectively reduced by siRNA. (A and B) BAECs were transiently transfected for 24 h with control siRNA (NsiRNA 20 nM), p110α siRNA (10 nM), or p85α siRNA (20 nM). After 48 h, the p110α or p85α subunit of PI3K was identified by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 3).

Fig. 5.

LysoPC induces PIP3 production and PIP3-TRPC6 colocalization. (A and B) BAECs were transiently transfected with NsiRNA, p110α siRNA, or p85α siRNA, then incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. TRPC6 externalization was detected by biotinylation assay (n = 4). (C and D) BAECs were pretreated with LY294002 (20 µM) for 1 h, then lysoPC. (C) TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay (n = 4). (D) TRPC6 was immunoprecipitated, and associated CaM or total TRPC6 was identified by immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (E) Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy identified PIP3 (green), TRPC6 (red), and PIP3-TRPC6 colocalization (yellow). Representative images of three experiments are shown. Columns 1, 2, 4, 5 show 40× magnification; column 3 shows 100× magnification. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (F) PIP3 production was measured by ELISA and expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4, *P < 0.001 compared with control and **P < 0.02 compared with lysoPC alone). (G) WT or TRPC6−/− MAECs were incubated with lysoPC (10 µM). PIP3 production was measured by ELISA and expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.01 compared with WT and **P < 0.01 compared with TRPC6−/−).

To confirm the ability of lysoPC to activate PI3K, PIP3 production was assessed. Immunofluorescence microscopy studies demonstrated that lysoPC stimulated PIP3 production, but LY294002 blocked this increase (n = 3, Fig. 5E). Based on overlapping colors, PIP3 and TRPC6 colocalized to discrete areas of the cell membrane (n = 3, Fig. 5E). LysoPC (12.5 µM) increased PIP3 production measured by ELISA 2.0 ± 0.3-fold (n = 4, P < 0.001 compared with control), but pretreatment with LY294002 blocked PIP3 production in response to lysoPC (n = 4, Fig. 5F). These studies were consistent with lysoPC activating PI3K.

To determine if PI3K activation required TRPC6, PIP3 production was assessed in WT and TRPC6−/− MAECs. Basal PIP3 production measured by ELISA was similar in both cell types. LysoPC increased PIP3 production in both WT MAECs and TRPC6−/− MAECs with a 2.3 ± 0.1-fold and 2.2 ± 0.1-fold increase, respectively, compared with control (n = 3, Fig. 5G). These results were confirmed by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (n = 3, Fig. S8). These findings suggested that lysoPC-induced PI3K activation and PIP3 production did not require TRPC6.

Fig. S8.

PIP3 production in WT or TRPC6−/− MAECs. WT or TRPC6−/− MAECs were incubated with lysoPC (10 µM) for 15 min. PIP3 was identified by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (n = 3). Representative images are shown. Columns 1 and 2 show 40× magnification; column 3, 100× magnification. (Scale bar, 100 µm.)

CaM Phosphorylation at Tyr99 Regulates PI3K Activation.

The role of CaM phosphorylation in CaM binding to the p85 subunit and the interaction of p85 and p110 subunits was assessed. In BAECs incubated with lysoPC, the association of p85α and phospho-CaM as well as CaM was increased (n = 4, P < 0.001 compared with control; Fig. 6A). The similar density of bands for phospho-CaM and total CaM suggested that the majority of the CaM associated with p85α was phosphorylated. Therefore, using BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM or Phe99-CaM, the requirement of CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 was assessed. LysoPC increased the association of p85α and WT-CaM (3.92 ± 0.4-fold increase compared with control, P < 0.01) but not p85α and Phe99-CaM (n = 4, Fig. 6B), suggesting that CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 was required for lysoPC-stimulated CaM-p85α subunit association.

Fig. 6.

In BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM, lysoPC does not induce CaM-PI3K association, PIP3 production, PIP3-TRPC6 colocalization, or inhibit EC migration. (A) BAECs were incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min. The p85α subunit of PI3K was immunoprecipitated, and associated phospho-CaM(Tyr99), CaM, or total p85α subunit identified by immunoblot analysis (n = 4). (B–F) BAECs were transiently transfected to overexpress WT-CaM or Phe99-CaM. (B–D) BAECs were incubated with lysoPC. (B) The p85α subunit of PI3K was immunoprecipitated, and associated CaM or total p85α subunit was identified by immunoblot analysis (n = 4). (C) Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was used to identify PIP3 (green), TRPC6 (red), or PIP3-TRPC6 colocalization (yellow). Representative images of three experiments are shown. Columns 1, 2, 3, 5 show 40× magnification; column 4 shows 100× magnification. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (D) PIP3 production was measured by ELISA (n = 3). Results are represented as mean ± SD (*P < 0.01 compared with WT-CaM control; **P < 0.001 compared with WT-CaM incubated with lysoPC). (E) Migration was assessed after 24 h in the presence or absence of lysoPC (12.5 µM). Arrow identifies the starting line of migration. (Upper) Representative images of three experiments are shown 40× magnification. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (Lower) Migration represented as mean ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.001 compared with WT-CaM control, **P < 0.001 compared with Phe99-CaM control, and †P < 0.001 compared with WT-CaM with lysoPC).

Under control conditions, PIP3 localization by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was similar in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM or Phe99-CaM. After incubation with lysoPC, staining for PIP3 increased in the membrane of BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM but not in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 3, Fig. 6C). Discrete areas of colocalization of PIP3 and TRPC6 were noted in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM but not in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 3, Fig. 6C). Basal PIP3 production measured by ELISA was similar in both groups of BAECs (Fig. 6D). After incubation with lysoPC, PIP3 production in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM increased 2.3 ± 0.2-fold compared with baseline (P < 0.01), but did not change in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 3, Fig. 6D). These results supported the pivotal role of CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 in lysoPC-induced PI3K activation and TRPC6 externalization.

Basal migration of BAECs transiently transfected with empty vector or overexpressing WT-CaM or Phe99-CaM was similar. LysoPC inhibited BAEC migration by 63% in BAECs overexpressing WT-CaM, but only by 30% in BAECs overexpressing Phe99-CaM (n = 3, P < 0.001 compared with WT-CaM with lysoPC; Fig. 6E). These results revealed for the first time to our knowledge that CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 contributes to lysoPC's antimigratory activity by activating PI3K and promoting externalization of TRPC6. Our model for the proposed sequence of events is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Model of events following EC exposure to lysoPC. LysoPC activates a Src family kinase that phosphorylates (P) CaM at Tyr99. Phosphorylated CaM dissociates from TRPC6. TRPC6 is phosphorylated. Phosphorylated CaM binds to the p85α subunit of PI3K, activating it. The increased PIP3 in the plasma membrane (PM) serves to anchor TRPC6 there. When CaM is mutated at Tyr99 to Phe99, this sequence of events is disrupted. LysoPC might initiate these events through receptor activation or release of arachidonate and activation of arachidonate-regulated Ca2+ channels. Neither the identity of the receptor (R) nor the identity of the channel activated to allow entry of the initial local Ca2+ trigger are known (brown colored).

Discussion

CaM contributes to the regulation of TRPC channels, including TRPC6. In HEK cells stably transfected to overexpress TRPC6, CaM inhibitors decrease CaM binding to TRPC6, TRPC6 channel activity, and Ca2+ influx in response to receptor activation by carbachol when intracellular stores are depleted (21), suggesting that dissociation of CaM from TRPC6 results in decreased channel activity. CaM inhibitors, however, may decrease TRPC6 channel activity by blocking CaM's activation of PI3K. In fact, we find that CaM dissociation from TRPC6 is necessary but not sufficient for lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization (Fig. 1). When CaM is down-regulated with siRNA, decreasing CaM binding to TRPC6, TRPC6 is not externalized.

Phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 by a Src family kinase is required for lysoPC-induced dissociation of CaM from TRPC6. Activation of Src kinase requires Ca2+ and can occur as a result of increased [Ca2+]i (22, 23). In our previous study, we have shown lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization in BAECs was not blocked in Ca2+-free KR buffer or by using BAPTA/AM (25 µM) (3). At this concentration, BAPTA/AM blunts the global increase in [Ca2+]i, but may not chelate all Ca2+. Results of the present study, using a higher concentration of BAPTA/AM, suggest that a small increase in Ca2+ is required for kinase activation and CaM phosphorylation with subsequent TRPC6 externalization (Fig. 2).

The source of Ca2+ required for kinase activation is unclear. LysoPC could disrupt the membrane lipid bilayer affecting ion channels or acting as a detergent, but the concentration used is below the critical micellar concentration of 40–50 µM (1) and the membrane detergent, saponin, does not increase TRPC6 phosphorylation (Fig. S9A) as does lysoPC (3). LysoPC alters cell membrane microviscosity, potentially altering ion channel function, but preincubation with α-tocopherol, which restores microviscosity to normal (24), does not prevent lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization (Fig. S9B). Pertussis toxin does not alter lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization (Fig. S9C), suggesting that Gi-proteins are not involved. LysoPC can induce arachadonic acid release (25), causing Ca2+ entry through arachidonate-regulated Ca2+ channels (26). This could contribute to the Ca2+ needed for Src kinase activation and subsequent events.

Fig. S9.

TRPC6 externalization is not induced by saponin or blocked by membrane microviscosity stabilization or Gi-protein inhibition. (A) BAECs were incubated with the membrane detergent, saponin (0.005%), for 20 min. Incubation with lysoPC (12.5 µM) for 15 min served as a positive control. Tyrosine phosphorylation of TRPC6 was detected by immunoprecipitation of TRPC6, followed by immunoblot analysis using antiphosphotyrosine antibody. In aliquots removed after immunoprecipitation, total TRPC6 was determined by immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (B and C) BAECs were pretreated with (B) α-tocopherol (50 µM) overnight or (C) pertussis toxin (PTx, 1 μg/mL) for 24 h. LysoPC (12.5 µM) was added for 15–30 min, and TRPC6 externalization was determined by biotinylation assay. Total TRPC6 was assessed by immunoblot analysis of aliquots removed before incubation with streptavidin-agarose beads (n = 3).

Phosphoinositides, especially PIP3, bind to TRPC6, and have been reported to disrupt CaM binding and increase TRPC6 current (16). In our studies, lysoPC induces dissociation of TRPC6 and CaM, even when PI3K and PIP3 production are inhibited (Fig. 5D), suggesting that PIP3 binding is not required to displace CaM from TRPC6. Dissociation of CaM from TRPC6 by both PIP3 binding and CaM phosphorylation may contribute to TRPC6 externalization. Phospho-CaM, by promoting PI3K activation and increased PIP3 production, may create a feed-forward effect, causing a prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i that contributes to pathological effects of lysoPC, including inhibition of EC migration.

Although tethering of Ca2+ to CaM alters its protein affinity and the Ca2+-CaM complex regulates many proteins, our studies suggest that CaM phosphorylation at Tyr99 is essential in lysoPC-induced PI3K activation. CaM regulates PI3K activation by binding to an SH2 domain of the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K (17), and this can cause a conformational change that releases the p110 catalytic subunit from the inhibitory effects of the p85 subunit, increasing p110’s catalytic activity (27).

PI3K activation results in elevated levels of PIP3 and PIP3-TRPC6 association in the EC plasma membrane. Similarly, vasopressin-induced TRPC6 externalization is mediated by PI3K activation in smooth muscle cells (15). PI3K inhibition with LY294002 blocks lysoPC-induced PIP3 production and externalization of TRPC6 (Fig. 5). LY294002 can also inhibit PI4K, leading to reduced generation of PIP2 and depletion of membrane PIP2, but not at the low concentration (20 µM) used in our studies (15, 28). The role of PI3K in TRPC6 externalization is confirmed by down-regulating PI3K subunits (Fig. 5).

PIP3 formation is critical for lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization. PIP3 in the cell membrane can bind to TRPC6, specifically the C terminus, and promote anchoring of TRPC6-containing vesicles in the plasma membrane, increasing TRPC6 activity and [Ca2+]i (15, 16, 29). Membrane colocalization may be due to direct binding of TRPC6 to PIP3 or binding through a protein partner. PIP3 facilitates docking of proteins with a PH domain, and TRPC6 is reported to have two putative PH-like motifs (30), but their role in PIP3-TRPC6 interaction is unclear. PIP3 binding to a PH domain can induce conformational changes that affect protein function, or PIP3 binding can serve to colocalize proteins and regulate interactions such as oligomerization (31). On the other hand, TRPC6 might bind to PIP3 through a protein partner as has been reported for other TRPC proteins (32). Further studies are needed to determine if an adapter protein is required for TRPC6 binding to PIP3.

Materials and Methods

Expanded methods are available in SI Materials and Methods. Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cleveland Clinic.

The full-length human CaM cDNA (MGC-7) was obtained from ATCC. PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate cDNAs for mutant CaMs in which Tyr99 or Tyr138 was replaced with Phe or Asp (ExonBio), generating mutants Phe99-CaM, Asp99-CaM, or Phe138-CaM. Sequence analysis verified the mutations. BAECs at 60% confluence were transiently transfected with 2 μg of plasmids containing pcDNA3.1-myc-His, pcDNA 3.1-myc-His-WT-CaM, pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe99-CaM, pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Asp99-CaM, pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Phe138-CaM, and pcDNA3-TRPC6 using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

SI Materials and Methods

EC Culture.

Fresh adult bovine aortas were treated with collagenase before gentle scraping for isolation of bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) (3). The BAECs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM) with Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (1:1 vol/vol) containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS (HyClone Laboratories). BAECs between passages 4 and 10 were used for experiments.

Mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) were isolated from wild-type (WT) and TRPC6-deficient (TRPC6−/−) mice (33). Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic. Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). The aorta was removed, rinsed with medium, cut into rings (∼3 mm long), and placed into Matrigel-coated 35-mm tissue culture plates and cultured with modified culture medium (3). After 2–4 d, when MAECs started to grow out from the aortic ring, the aortic rings were removed. MAECs were harvested from the Matrigel-coated plates with dispase, then plated into a six-well plate coated with 0.2% gelatin and cultured in M199 medium with Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (4:1) with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and gentamicin (1 μg/mL). MAEC identity was verified by using immunostaining with anti-human von Willebrand factor polyclonal antibody (1:100, Dako). In case of mixed cell populations including smooth muscle cells or fibroblasts with MAECs, cloning of pure MAECs from the mixed cell population was done with a cloning disk (Millipore). MAECs in passage 3 or 4 were used for the experiments.

Protein Analysis by Immumoprecipitation.

Endothelial cells (ECs) were washed in tissue culture medium and made quiescent for 3 h in serum-free DMEM containing 0.1% gelatin before experiment conditions were applied. ECs were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 200 μM Na3VO4, 100 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche). Insoluble material was separated by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and supernatant was collected as clean soluble protein and measured. Immunoprecipitation of the target protein was done as previously described (3). Equal amounts of protein from the lysed sample were incubated with the antigen-specific antibody overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, Protein A/G Plus agarose beads were added to the lysate-antibody mixture at 4 °C under rotary agitation for 2 h. The beads were collected by pulse centrifugation and washed three times with ice-cold lysis buffer. The beads were resuspended in 40 μL 2× (wt/vol) Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, then centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was loaded in 4–20% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE for protein separation.

Protein Analysis by Immunoblot.

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (3). Proteins (60–80 μg/lane) from the sample were loaded in 4–20% (wt/vol) gradient SDS/PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and detected by antibodies specific for TRPC6 (1:200, Rockland), TRPC5 (1:250, University of California Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility), phosphotyrosine, clone 4G10 (1:500, Millipore), CaM (1:1,000, Millipore), phospho-CaM(Tyr99) (1:250, Millipore), phospho-CaM(Tyr138) (1:200, Millipore), phospho-CaM(Ser81/Thr79) (1:250, Millipore, Myc Tag (1:500, Millipore), p110〈 subunit of PI3K (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology), or p85〈 subunit of PI3K (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The signal was visualized by developing the X-ray film using a chemiluminescent reagent (Perkin-Elmer-Cetus), and protein band density was quantitated using NIH ImageJ software. To verify equal loading, membranes were reprobed for actin using antiactin antibody (Chemicon).

Detection of TRPC6 Externalization by Biotinylation Assay.

Biotinylation of EC membrane surface proteins was performed as previously described (3). Confluent BAECs, MAECs, or human EA.hy926 cells were cultured in 60-mm dishes, treated as appropriate, washed with ice-cold PBS, and incubated with 2 mg/mL Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Calbiochem) for 30 min at 4 °C. Reaction was terminated by washing twice with cold buffer containing 10 mM glycine. ECs were lysed in buffer (50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 200 μM Na3VO4, 100 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche) for 30 min at 4 °C. Lysates were passed through 20- and 25-gauge needles, cleared by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, and incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads for 18 h at 4 °C. Biotin-streptavidin complexes were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, washed three times with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 4× Laemmli buffer, and incubated at 60 °C for 30 min. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and identified by immunoblot analysis. Total TRPC6 was determined in an aliquot of lysate removed before incubation with streptavidin-agarose beads.

Overexpression of Mutant CaM in ECs.

The full-length human CaM cDNA (MGC-7) was obtained from ATCC. PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate cDNA for mutant CaM in which Tyr99 or Tyr138 was replaced with Phe (ExonBio), generating mutants Phe99-CaM or Phe138-CaM, respectively. Also, a mutant CaM in which Tyr99 was replaced with Asp was generated. Sequence analysis verified the mutations. To produce cells transiently overexpressing TRPC6 or CaM, 60–80% confluent BAECs were transfected for 16–24 h with 2–4 µg of plasmids for 16–24 h using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For overexpression of TRPC6, WT-CaM, or Phe99-CaM, BAECs were transfected using 2 µg of plasmids contained pcDNA3-human TRPC6, pcDNA3.1-myc-His-WT-CaM, or pcDNA 3.1-myc-His-Phe99-CaM, respectively. For overexpression of TRPC6 and WT-CaM, or TRPC6 and Phe99-CaM, BAECs were transfected using 2 µg of each of the appropriate two plasmids. The effectiveness of transfection was verified after 24–48 h by immunoblot analysis of TRPC6 using anti-TRPC6 antibody (1:200) or CaM using mouse anti-Myc Tag antibody (1:500).

Intracellular Calcium [Ca2+]i Measurement.

Transiently transfected BAECs with overexpression of WT-CaM, Phe99-CaM, TRPC6, TRPC6, and WT-CaM, or TRPC6 and Phe99-CaM, were used for measuring of [Ca2+]i. BAECs were cultured in glass coverslips until 60–70% confluent, then loaded with fura 2-AM (10 μM) for 20 min. Excess fura 2-AM was washed out by Krebs-Ringer (KR) buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 11 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4). A coverslip with fura 2-AM loaded BAECs was placed in a temperature-regulated (30 °C) chamber (Warner Instruments) on an Olympus 1X-81 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus America). Fluorescence of multiple individual cells was monitored simultaneously using an EasyRatioPro fluorescence imaging system with a DeltaRAM X multiwavelength illuminator (Photon Technology International) and a QuantEM:512SC electron multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics). Before data acquisition, background fluorescence was measured and automatically subtracted using EasyRatioPro. The relative change of [Ca2+]i was determined using the ratio of fura 2 fluorescence intensity at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm (340/380 ratio).

Down-regulation of Target Protein mRNA.

BAECs at 80% confluence were incubated with the small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex of CaM isoform 1 (20 nM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2, 20 nM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p85α subunit of PI3K (20 nM, Dharmacon), or p110α subunit of PI3K (10 nM, Dharmacon) for 24 h using a transfection kit (RNAiFect, Qiagen) and following the manufacturer's protocol. Also, a negative control siRNA (NsiRNA; Ambion), without homology to a known gene sequence, was used. Down-regulation of endogenous target protein level was confirmed after 48 h by immunoblot analysis.

EC Migration.

EC migration was assessed in a razor-scrape assay in 12-well tissue culture plates as previously described (4). Confluent ECs were incubated for 8–12 h in serum-free DMEM containing 0.1% gelatin. A sterile razor blade was pressed gently into the plastic plate to mark the starting line, then scraped laterally to remove cells on one side of that line. ECs were allowed to migrate for 24 h, then were fixed and stained with a modified Wright-Giemsa stain (Sigma). An observer blinded to the experimental conditions quantitated cell migration from the images taken of three fields corresponding to a starting line length of 1.34 mm with the use of a digital CCD camera mounted on a phase-contrast microscope. Results were expressed as mean ± SD of each experiment and represented data are from triplicate wells.

PIP3 Detection and PIP3-TRPC6 Colocalization.

To detect PIP3 by confocal microscopy, ECs were grown on 25-mm coverslips until 60% confluent, made quiescent in serum-free medium for 3 h, and then incubated with PBS or lysoPC (1-palmitol-2-hydroxy-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine; Avanti Polar Lipids). Cells were fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min at 4 °C, washed, blocked with 1:1 mixture of 5% (vol/vol) normal goat serum and 3% (wt/vol) BSA for 2 h at room temperature, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-PIP3 antibody (1:100; Echelon) for 16 h at 4 °C. The equivalent concentration of mouse primary antibody isotype control (Invitrogen) was used as a negative control. The coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

To determine PIP3 by ELISA, confluent ECs were made quiescent in serum-free medium for 5 h. PIP3 was extracted from EC using a PIP3 mass ELISA kit (Echelon) following the manufacturer's protocol. Extracted PIP3 in samples, controls, and known standards were measured at 450 nm using SpectraMAX 190 plate reader (Molecular Devices).

To determine PIP3-TRPC6 colocalization by confocal microscopy, cells were fixed, washed, and blocked as above, then incubated with mouse anti-TRPC6 antibody (1:100) for 4 h followed by Alexa 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1,000; Molecular Probes) for 2 h. Next, cells were washed and incubated with FITC-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-PIP3 antibody (1:100) for 12 h at 4 °C. Negative controls included omitting the primary antibody and replacing the primary antibody with an isotype control. TRPC6 and PIP3 were identified with filters for the specific fluorophore of interest, then images of the same fields were merged to assess colocalization.

Statistics.

Experiments were performed in triplicate with ECs isolated from at least three different animals. Values were presented as the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed by Student's t test or ANOVA and considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-064357 (to L.M.G.) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Project Z01-ES-101684 (to L.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600371113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Murugesan G, Fox PL. Role of lysophosphatidylcholine in the inhibition of endothelial cell motility by oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(12):2736–2744. doi: 10.1172/JCI118728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tran POT, Hinman LE, Unger GM, Sammak PJ. A wound-induced [Ca2+]i increase and its transcriptional activation of immediate early genes is important in the regulation of motility. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246(2):319–326. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhuri P, et al. Elucidation of a TRPC6-TRPC5 channel cascade that restricts endothelial cell movement. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(8):3203–3211. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri P, Colles SM, Damron DS, Graham LM. Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits endothelial cell migration by increasing intracellular calcium and activating calpain. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(2):218–223. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000052673.77316.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenbaum MA, Chaudhuri P, Graham LM. Hypercholesterolemia inhibits re-endothelialization of arterial injuries by TRPC channel activation. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(4):1040–1047.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saimi Y, Kung C. Calmodulin as an ion channel subunit. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:289–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.100301.111649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J, et al. Identification of common binding sites for calmodulin and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors on the carboxyl termini of trp channels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):21303–21310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102316200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Z, et al. Activation of Trp3 by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors through displacement of inhibitory calmodulin from a common binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(6):3168–3173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu MX. Multiple roles of calmodulin and other Ca(2+)-binding proteins in the functional regulation of TRP channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451(1):105–115. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi J, et al. Multiple regulation by calcium of murine homologues of transient receptor potential proteins TRPC6 and TRPC7 expressed in HEK293 cells. J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 2):415–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukami Y, Nakamura T, Nakayama A, Kanehisa T. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues of calmodulin in Rous sarcoma virus-transformed cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(12):4190–4193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassa BV, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates EGF receptor activation and mesangial cell proliferation: Regulatory role of Src and PKC. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771(11):1364–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benaim G, Villalobo A. Phosphorylation of calmodulin. Functional implications. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(15):3619–3631. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cayouette S, Lussier MP, Mathieu E-L, Bousquet SM, Boulay G. Exocytotic insertion of TRPC6 channel into the plasma membrane upon Gq protein-coupled receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):7241–7246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monet M, Francoeur N, Boulay G. Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and PTEN protein in mechanism of activation of TRPC6 protein in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(21):17672–17681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon Y, Hofmann T, Montell C. Integration of phosphoinositide- and calmodulin-mediated regulation of TRPC6. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyal JL, et al. Calmodulin activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(45):28183–28186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rikitake Y, et al. Regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK2 in vascular endothelial cells by lysophosphatidylcholine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(1):H266–H274. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie J, et al. Analysis of the calcium-dependent regulation of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(10):2322–2335. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lev S, et al. Protein tyrosine kinase PYK2 involved in Ca(2+)-induced regulation of ion channel and MAP kinase functions. Nature. 1995;376(6543):737–745. doi: 10.1038/376737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulay G. Ca(2+)-calmodulin regulates receptor-operated Ca(2+) entry activity of TRPC6 in HEK-293 cells. Cell Calcium. 2002;32(4):201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda M, et al. Shear stress stimulation of p130(cas) tyrosine phosphorylation requires calcium-dependent c-Src activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(38):26803–26809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Sudol M, Hanafusa H, Krueger J. Increased tyrosine kinase activity of c-Src during calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(17):8298–8302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh PK, et al. Membrane microviscosity regulates endothelial cell motility. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(11):894–900. doi: 10.1038/ncb873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong JT, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates the release of arachidonic acid in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(12):6830–6836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuttleworth TJ. Arachidonic acid, ARC channels, and Orai proteins. Cell Calcium. 2009;45(6):602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoelson SE, et al. Specific phosphopeptide binding regulates a conformational change in the PI 3-kinase SH2 domain associated with enzyme activation. EMBO J. 1993;12(2):795–802. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong D, Dan S, Yamazaki K, Yamori T. Inhibition profiles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors against PI3K superfamily and human cancer cell line panel JFCR39. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(6):1111–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng PH, et al. The canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel as a putative phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium entry system. Biochemistry. 2004;43(37):11701–11708. doi: 10.1021/bi049349f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T. Transient receptor potential channels meet phosphoinositides. EMBO J. 2008;27(21):2809–2816. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottomley MJ, Salim K, Panayotou G. Phospholipid-binding protein domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436(1-2):165–183. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton KA, et al. Enkurin is a novel calmodulin and TRPC channel binding protein in sperm. Dev Biol. 2004;274(2):426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietrich A, et al. Increased vascular smooth muscle contractility in TRPC6-/- mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(16):6980–6989. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6980-6989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]