Significance

Understanding the interplay between excitation and inhibition in feedforward and recurrent circuits is essential for elucidating the mechanisms of cortical function. However, disentangling the relative contributions of feedforward or recurrent inhibition to cortical responses has been difficult. This study capitalizes on the unique laminar architecture of the piriform cortex to investigate feedforward and recurrent circuits in isolation. We find that feedforward inhibition and excitation are balanced, whereas recurrent inhibition dominates intracortical excitation. Furthermore, we find that feedforward and recurrent circuits differentially recruit the three classes of cortical excitatory neurons, functionally segregating their roles in the cortical representation of olfactory information. This study provides insight to circuit mechanisms that regulate subthreshold and suprathreshold processing of afferent input to the cortex.

Keywords: cortex, inhibition, olfaction

Abstract

Throughout the brain, the recruitment of feedforward and recurrent inhibition shapes neural responses. However, disentangling the relative contributions of these often-overlapping cortical circuits is challenging. The piriform cortex provides an ideal system to address this issue because the interneurons responsible for feedforward and recurrent inhibition are anatomically segregated in layer (L) 1 and L2/3 respectively. Here we use a combination of optical and electrical activation of interneurons to profile the inhibitory input received by three classes of principal excitatory neuron in the anterior piriform cortex. In all classes, we find that L1 interneurons provide weaker inhibition than L2/3 interneurons. Nonetheless, feedforward inhibitory strength covaries with the amount of afferent excitation received by each class of principal neuron. In contrast, intracortical stimulation of L2/3 evokes strong inhibition that dominates recurrent excitation in all classes. Finally, we find that the relative contributions of feedforward and recurrent pathways differ between principal neuron classes. Specifically, L2 neurons receive more reliable afferent drive and less overall inhibition than L3 neurons. Alternatively, L3 neurons receive substantially more intracortical inhibition. These three features—balanced afferent drive, dominant recurrent inhibition, and differential recruitment by afferent vs. intracortical circuits, dependent on cell class—suggest mechanisms for olfactory processing that may extend to other sensory cortices.

The recruitment of inhibition is an essential feature of cortical processing. Feedforward and recurrent inhibitory circuits have been implicated in controlling the timing, strength, and tuning of cortical responses (for review, see ref. 1). In sensory cortices, including the olfactory cortex, neural responses to sensory stimuli depend on the relative balance of inhibition with respect to excitation in both feedforward and recurrent pathways (2–7). Moreover, numerous theoretical studies have suggested that balanced cortical networks underlie the selectivity, sparseness, and correlations of cortical activity (8–15). These studies highlight the importance of quantifying the relationship between excitation and inhibition in cortical networks. However, isolating the contributions of feedforward vs. recurrently evoked inhibition to cortical responses is difficult because these circuits are often coactive and frequently share interneurons (16–18). The piriform cortex is an ideal system to address this issue because the interneurons responsible for feedforward and recurrent inhibition differ by class and laminar location and, thus, are differentially recruited by afferent and intracortical excitation (19–22).

The piriform cortex is a trilaminar cortex responsible for processing olfactory stimuli. Principal excitatory neurons are found in layer (L) 2/3 and send dendrites to L1, where they receive odor-related excitation directly from the olfactory bulb via the lateral olfactory tract (LOT) (23). LOT afferents also drive horizontal and neurogliaform inhibitory interneurons within L1, yielding feedforward inhibition of principal neurons (24). Within the cortex, principal neurons send axon collaterals throughout L2/3 and to an intracortical fiber tract in L1b (25, 26). Intracortical excitation recruits a number of interneuron classes within L2/3 that, in turn, provide recurrent inhibition to principal neurons (20, 24, 27, 28). Stimulation of the LOT evokes short- latency feedforward inhibition that targets principal neuron dendrites, as well as long-latency, recurrent inhibition that is somatic (24, 28, 29). These findings are consistent with the different laminar locations of inhibitory interneurons mediating feedforward and recurrent inhibition respectively.

Previous studies have shown that electrical stimulation of the LOT as well as odors recruit mixed feedforward and recurrent inhibition in vivo (3, 4, 30, 31). However, in vivo and in vitro studies focusing on different principal neuron classes have led to conflicting reports of the relative contributions of feedforward and feedback inhibition during afferent odor processing (3, 24, 27, 28, 32). Furthermore, because of the disynaptic nature of inhibition, estimates of feedforward or recurrent inhibitory strength depend on the quality of afferent and intracortical excitatory recruitment, which varies with the different stimulation protocols used in each study. Here, we resolve these discrepancies by comparing feedforward and recurrent inhibition evoked by direct optical activation of interneurons that express channelrhodopsin (ChR2) (33), as well as electrical stimulation of excitatory pathways in all three classes of principal neuron in the anterior piriform cortex (APC).

In the APC, principal excitatory neuron classes differ in laminar location and in the proportion of afferent vs. intracortical excitatory input received (34–37). Within L2, semilunar cells (SLCs) receive predominantly afferent excitation, whereas superficial pyramidal cells (sPCs) receive weaker afferent and stronger intracortical excitatory drive. In L3, deep pyramidal cells (dPCs) receive minimal afferent, but substantial intracortical excitation. Given these differences in excitatory drive, we hypothesized that inhibition mediated by feedforward and recurrent inhibitory circuits also differs between principal neuron classes. In this study, we find that principal neuron classes are weakly inhibited by L1 interneurons that mediate feedforward inhibition, compared with L2/3 interneurons that provide strong recurrent inhibition. As predicted, feedforward inhibitory strength varies in a manner consistent with the amount of afferent excitation received by each class of principal neuron. In contrast, intracortical stimulation of L3 evokes strong recurrent inhibition that dominates excitation in all classes. Moreover, excitatory and inhibitory profiles differ between SLCs, sPCs, and dPCs. Taken together, our results demonstrate that inhibitory circuits in the piriform cortex provide both balanced feedforward inhibition and dominant recurrent inhibition, as well as segregate principal excitatory neuron classes during cortical processing.

Results

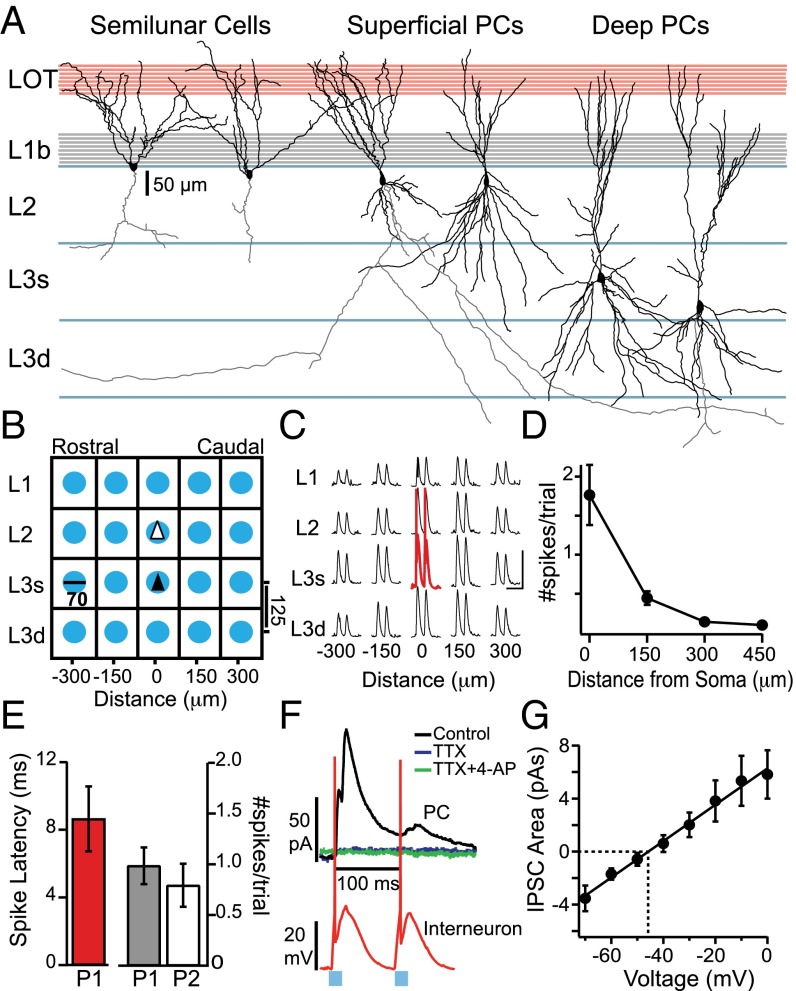

We investigated the strength of inhibition onto principal excitatory neurons (Fig. 1A) in sagittal slices of APC from transgenic mice that express ChR2 in the majority of interneurons under the vGAT promoter (33). For each principal neuron, we obtained the spatial profile of inhibition based on the laminar locations of interneuron somas. Briefly, interneurons were focally activated by using light spots (Methods) in a 5 × 4 grid pattern surrounding the principal neuron (Fig. 1B). Focal light stimuli reliably recruited action potentials when centered on interneuron somas, [1.76 ± 0.38 spikes (spks) per trial, two light pulses per trial] but not at off-soma locations >150 µm from the soma (0.44 ± 0.09 spks per trial, P = 1.8E-06, n = 14; Fig. 1 C and D). It is possible that interneuron classes could respond differently to optogenetic activation. Hence, we classified neurons as regular spiking (RS, n = 6) and fast spiking (FS, n = 6) based on intrinsic membrane and spiking properties (Methods). Two interneurons were not categorized. Spike responses did not differ between RS and FS cells for on-soma (P = 0.38) or off-soma (P = 0.07) optogenetic stimulation. In all cells, spikes were evoked within 8.6 ± 1.9 ms of the onset of the first light pulse (98 ± 18% of trials) but failed on the second pulse in ∼20% of trials (Fig. 1E). For this reason, only inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) evoked by the first light pulse were analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. (A) Schematic of laminar locations of recorded neurons. Neurolucida reconstructions corresponding to SLCs superficial and dPCs are shown. [Scale bar: 50 µm (for traces only).] (B) Schematic of stimulation grid for light spots (70-µm diameter) directed at locations in L1, L2, and superficial (s) and deep (d) L3 (125 µm between sites) as well as along the rostral–caudal axis (150 µm between sites). Recording sites are indicated by triangles for SLCs and sPCs (white) and dPCs (black). (C) Response of a representative interneuron to light activation of grid locations. Neuron only spiked in response to light directed at soma (red trace), and spikes were truncated. [Scale bars: 20 mV (vertical); 200 ms (horizontal).] (D) Number of spikes per trial vs. stimulation distance from soma (n = 14 interneurons). (E, Left) Average latency to first spike relative to light onset at soma. (E, Right) Average number of spikes on the first and second light pulses. (F) Representative traces from interneuron (red, spikes) and L3 dPC (black, IPSC) aligned to light onset (neurons were not recorded simultaneously). In the same dPC, light-evoked IPSCs were lost in the presence of TTX and could not be recovered by the addition of 4-AP. (G) Average IPSC strength (area, pA⋅s) at different holding potentials in response to light directed at the soma. On average, IPSCs reversed at approximately −45 mV (dashed lines).

Evoked IPSCs were recorded in SLCs, sPCs, or dPCs that were voltage clamped near 0 mV (Fig. 1F). IPSCs were abolished in the presence of the sodium channel antagonist tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 µm) and the potassium channel agonist, 4-aminopyradine (4-AP; 100 µm) for light intensities up to 1 mW (n = 4), suggesting that direct terminal release does not contribute substantially to our results (Fig. 1F). Thus, the spatial profiles of inhibitory currents reflect the somatic locations of the interneurons rather than synaptic locations on the principal neurons. Near-rest (−70 mV) IPSCs were outward currents that reversed between −50 and −40 mV (n = 8; Fig. 1G).

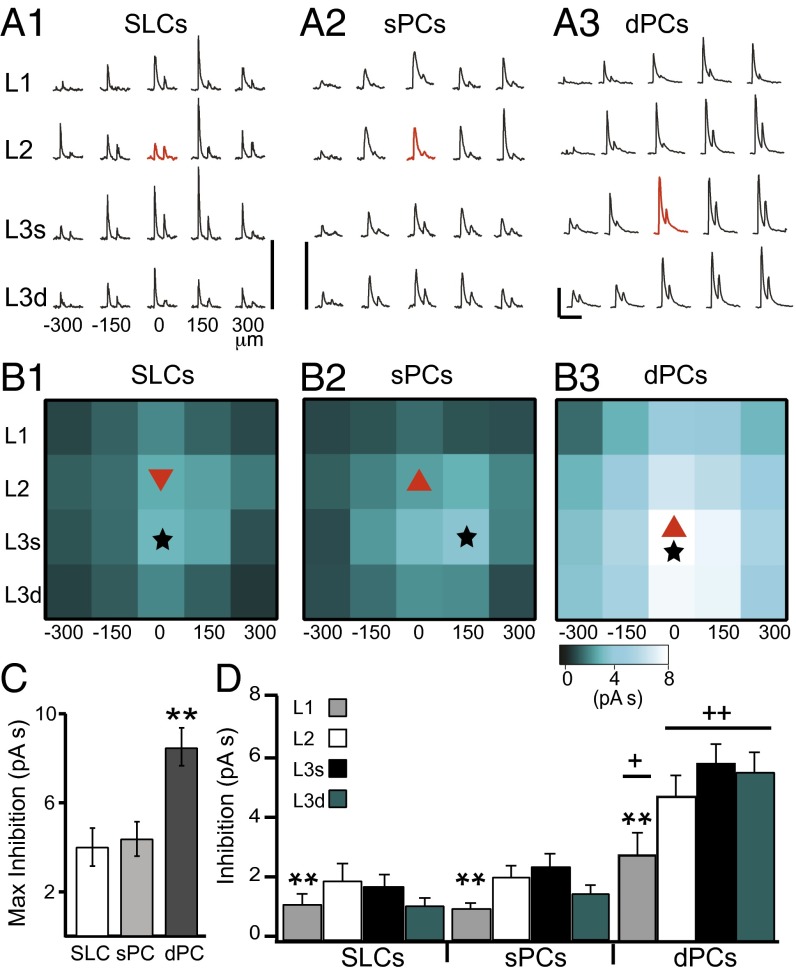

In Fig. 2A, IPSCs recorded during grid stimulation are shown for a representative SLC, sPC, and dPC. Similar results have been obtained using glutamate uncaging (38). Because IPSCs likely reflect population responses, the strength of inhibition was quantified as the area (pA⋅s) under the first peak of the trial-averaged IPSC evoked at each location. For each cell class, these values were averaged across neurons at each grid location and presented as a heat map (Fig. 2B). To obtain laminar averages, inhibition was averaged across rostral–caudal position for each layer and then averaged across neurons within class (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Spatial profiles of inhibition differ between principal neuron classes. (A) IPSCs in response to grid stimulation for a representative neuron from each class (A1: SLCs; A2: sPCs; A3: dPCs). Red traces indicate responses when light was centered on the soma. [Scale bars: 100 pA (vertical); 200 ms (horizontal).] (B) The strength of inhibition (area, pA⋅s) from each grid location averaged across neurons of the same class (B1, SLCs; B2, sPCs; B3, dPCs). Location of recorded neuron is indicated by a red triangle. Location of strongest average inhibition is indicated by a black star. (C) The average maximum inhibition for each class regardless of grid location. **P < 0.01. (D) The average inhibition across all sites in a layer, averaged across all neurons of the class. In all classes, inhibition from L1 was significantly less than L2 or L3. **P < 0.01. dPCs received significantly stronger inhibition in all layers than SLCs or sPCs. +P <0.05; ++P <0.01 (unpaired, two tailed, t tests).

Comparison of the inhibitory spatial profiles of the principal neuron classes yielded three striking findings. First, the majority of cells [60% SLCs (n = 13), 64% sPCs (n = 14), and 88% dPCs (n = 14)] received the maximal inhibition from a location in L3 (black stars, Fig. 2B). In the case of SLCs and sPCs, this finding meant that interneurons nearest to the soma did not necessarily provide the strongest inhibition. Second, inhibitory strength recorded at the location of maximal inhibition did not differ between SLCs and sPCs (SLCs: 3.6 ± 0.69 pA⋅s; sPCs 3.6 ± 0.69 pA⋅s; P = 0.46) but was significantly stronger in dPCs (8.6 ± 0.84 pA⋅s; **P = 9.0E-4; Fig. 2C). Likewise, the average laminar inhibition did not differ between SLCs and sPCs, but dPCs received significantly stronger inhibition from all layers compared with L2 neurons (+P < 0.05; ++P < 0.01; Fig. 2D). Finally, in all cell classes, light activation of L1 sites produced the weakest IPSCs compared with L2 and L3 sites (**P < 0.01; Fig. 2D). All of these findings suggest that, at the soma, recurrent inhibition provided by L2/3 is stronger than feedforward inhibition from L1.

Balanced Feedforward Excitation and Inhibition.

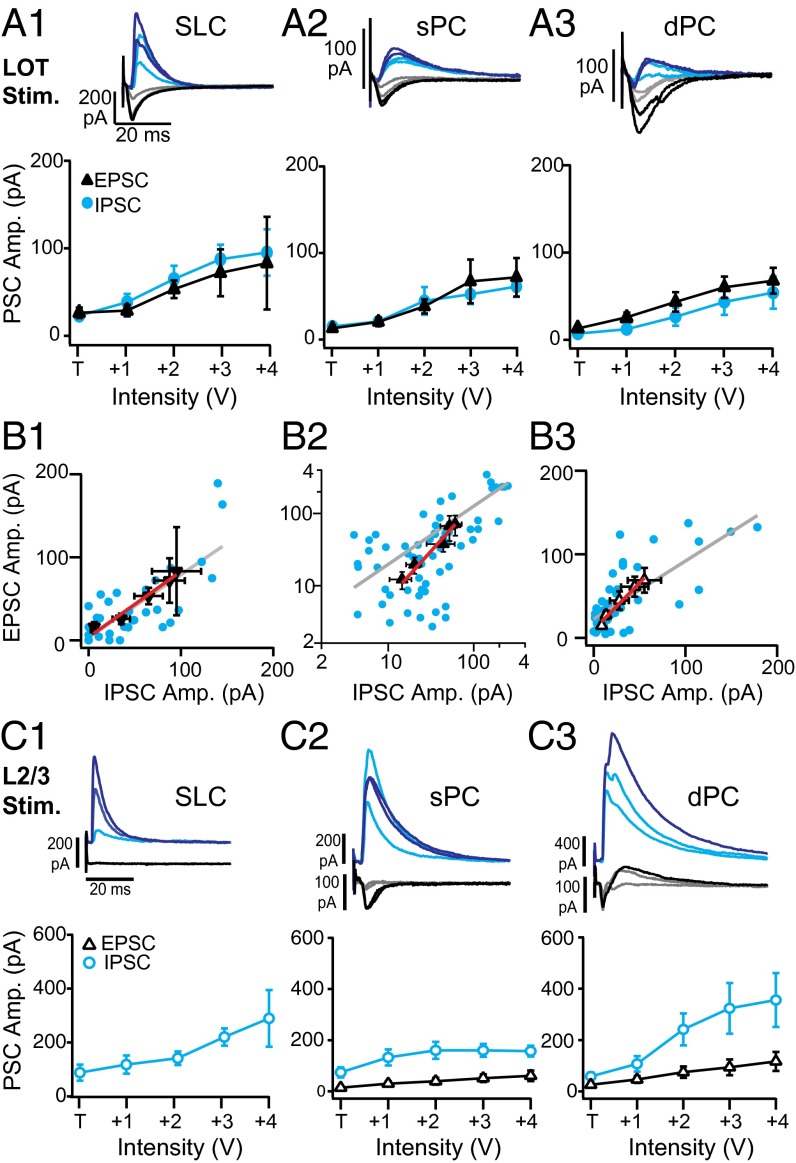

Optical activation of interneurons suggests that afferent excitation from the LOT (L1a) drives weak feedforward inhibition through L1 interneurons compared with the recruitment of recurrent inhibition by intracortical excitation. To investigate the relationship between excitation and inhibition in feedforward and recurrent circuits, we electrically stimulated (ES) the LOT or L2/3 respectively to compare evoked excitation and inhibition in the three cell classes. In all cases, stimulation strength was set at the threshold voltage (T) required to reliably elicit a PSC (either excitatory or inhibitory). To obtain an intensity–response curve, the stimulus voltage was then increased from T in 1-V increments (Fig. 3A). Unless otherwise stated, all measurements and statistical tests were taken at the midpoint of these curves.

Fig. 3.

Feedforward and recurrent excitation and inhibition. (A) Analysis of synaptic currents in principal neurons in response to electrical stimulation of the LOT for intensities that increase in 1-V increments from threshold (T) for evoking a PSC. (A, Upper) EPSCs (gray to black) and IPSCs (light to dark blue) in response to increasing intensity for an SLC (A1), sPC (A2), and dPC (A3). (A, Lower) Average EPSC (black triangles) and IPSC (blue circles) amplitudes for increasing stimulation intensity in SLCs (A1; n = 9), sPCs (A2, n = 12), and dPCs (A3; n = 9). (B) EPSC vs. IPSC amplitude for individual neurons at various stimulation intensities (blue circles) and linear fit (gray line). Average PSC amplitudes and linear fit are plotted as well (black triangles, red line). (C) Analysis of synaptic currents in principal neurons in response to L2/3 electrical stimulation for intensities that increase in 1-V increments from threshold (T) for evoking a PSC. (C, Upper) EPSCs (gray to black) and IPSCs (light to dark blue) in response to increasing intensity for an SLC (C1), sPC (C2), and dPC (C3). Note differences in scale bars for excitation and inhibition. (C, Lower) Average EPSC (black triangles) and IPSC (blue circles) amplitudes across SLCs (C1; n = 8), sPCs (C2; n = 13), and dPCs (C3; n = 14).

For LOT stimulation, T was significantly lower in SLCs (2.8 ± 0.36 V; P < 0.05) than sPCs (4.5 ± 0.48 V) or dPCs (4.6 ± 0.60 V). Because electrical and optogenetic stimulation regimes differ, we compared the area (pA⋅s) of evoked IPSCs during maximal LOT stimulation (T + 4V) and the average light evoked inhibition (area; pA⋅s) across L1 sites. IPSC strength did not differ between LOT and optogenetic stimulation (L1) in SLCs (LOT: 0.91 ± 0.14, L1: 1.15 ± 0.36), sPCs (LOT: 1.1 ± 0.29; L1: 0.94 ± 0.18), or dPCs (LOT: 1.8 ± 0.38; L1: 2.8 ± 0.73; P > 0.05, t test). This finding suggests that L1-mediated inhibition evoked in light activated and electrical regimes is comparable.

This relatively weak electrical stimulation regime was chosen to minimize polysynaptic activity and contamination of afferent responses by intracortical recruitment. To further reduce the possibility of analyzing polysynaptic responses during electrical stimulation, the peak amplitudes (rather than area) of the shortest-latency PSCs were used to compare EPSC and IPSC strength. In all neuron classes, IPSC onsets (in milliseconds: SLCs, 3.1 ± 0.46; sPCs, 4.3 ± 0.56; dPCs, 4.7 ± 0.79) followed EPSC onsets (in milliseconds: SLCs, 2.0 ± 0.13; sPCs, 2.2 ± 0.22; dPCs, 2.4 ± 0.19) with a short delay (1–2 ms) indicative of disynaptic feedforward inhibition.

In total, 9/9 SLCs and 12/12 sPCs, but only 9/14 dPCs (64%), received excitation during LOT stimulation. At threshold, SLCs received significantly stronger excitation (31 ± 9 pA) than SPCs (12 ± 3 pA; P = 0.02) or dPCs (14 ± 3 pA; P = 0.04), consistent with previous reports (36, 39). However, the midpoint excitatory strength did not differ between SLCs (60 ± 9 pA), sPCs (41 ± 9 pA), and dPCs (44 ± 11 pA; P > 0.05) (Fig. 3A). We next compared the strength of EPSCs and IPSCs in each class of principal neuron (Fig. 3 A and B). In SLCs and sPCs, inhibitory strength approximately matched excitation at most stimulation intensities (Fig. 3A). The midpoint IPSC strength (SLCs: 68 ± 17 pA, P = 0.22; sPCs: 46 ± 24 pA, P = 0.64) did not differ from excitation (above). In dPCs, inhibition was significantly weaker than excitation at the midpoint (28 ± 10 pA; P = 0.05), but did not differ at other stimulation intensities. The correlation between EPSC and IPSC strength was assessed for all individual EPSC–IPSC pairs in each neuron (Fig. 3B, blue circles), as well as for the average PSC strengths across neurons (black triangles). In all cases, the correlations were close to 1 for individual pairs (SLCs: 0.76 ± 0.12, R = 0.75, P = 1E−5; sPCs 1.0 ± 0.1, R = 0.8, P = 1E−5; dPCs 0.69 ± 0.09, R = 0.738, P = 1E−5) and average strengths (SLCs: 0.79 ± 0.06, R = 0.75, P = 3E−3; sPCs 1.3 ± 0.20, R = 0.96, P = 0.009, dPCs: 1.1 ± 0.11, R = 0.98, P = 0.003). These results suggest that feedforward excitation and inhibition are approximately balanced at low stimulation intensities.

Recurrent Inhibition Dominates Excitation.

Previous studies used higher LOT stimulation intensities or multiple pulses that evoked spike responses in excitatory neurons and recruited recurrent inhibition from L2/3 interneurons (27, 28). To investigate excitation and inhibition recruited by intracortical circuits in the absence of afferent drive, we electrically stimulated the border of L2/3. Inhibition (area, pA⋅s) during ES was again comparable to the average light-evoked inhibition from superficial L3 in SLCs (ES: 2.5 ± 0.74, L3: 1.74 ± 0.36), sPCs (ES: 3.5 ± 0.72; L3: 2.18 ± 0.41), and dPCs (ES: 6.4 ± 3.1; L3: 5.8 ± 0.66). Intensity–response curves were generated with thresholds between 5 and 7 V that did not differ between classes. All sPCs and dPCs recorded received both excitation and inhibition. However, in all eight SLCs, excitation could not be discerned. Consistent with disynaptic recruitment of inhibition, EPSCs (in milliseconds, sPCs: 2.6 ± 0.4; dPCs: 3.4 ± 0.5) significantly preceded IPSCs (in milliseconds, sPCs: 3.7 ± 0.4; dPCs: 4.8 ± 0.4; P < 0.05). In SLCs, IPSC latencies were 3.6 ± 0.4 ms.

In all neuron classes, inhibition was significantly stronger than excitation in response to L2/3 stimulation (Fig. 3C). Despite the absence of L2/3 excitation, SLCs received robust inhibition (198 ± 42 pA) (Fig. 3 C1). Further, IPSCs were significantly stronger than EPSCs in both sPCs (IPSC: 159 ± 32 pA, EPSC: 39 ± 13 pA; P = 0.004) and dPCs (IPSC: 323 ± 98 pA, EPSC: 75 ± 21 pA, P = 0.02) (Fig. 3 C2 and C3). Finally, in SLCs, sPCs, and dPCs, inhibition evoked by L2/3 stimulation was significantly greater than that evoked by LOT stimulation (comparison of midpoints; SLCs, P = 0.03; SPCs, P = 0.007; dPCs, P = 0.015).

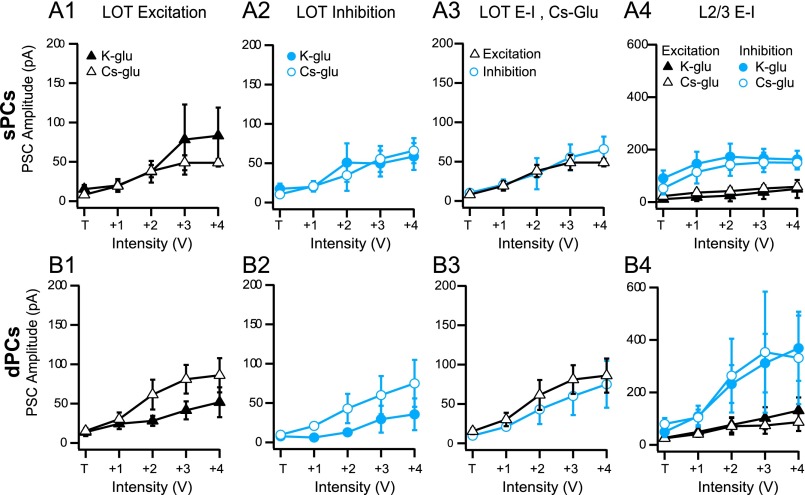

Notably, LOT-evoked currents may appear weaker (or even absent in dPCs) due to dendritic filtering compared with somatic synapses from L2/3 inhibition. A subset of our recordings in sPCs (n = 5/13) and dPCs (n = 6/14) were performed with Cs–gluconate internal solution (Methods) to enhance dendritic space clamp. EPSC and IPSC amplitudes evoked by LOT or L3 stimulation did not significantly differ at any intensity in either cell class compared with recordings with K-gluconate solution (Fig. S1). Further, the reliability of LOT input to dPCs was comparable in both solutions (Cs+: 4/6 (66%) neurons, K+: 5/8 (63%) neurons). These results are consistent with previous findings that pyramidal cell (PC) dendrites in piriform cortex minimally filter inputs (40). Nonetheless, in Cs+ recordings, LOT-evoked excitation and inhibition were balanced, whereas L2/3-evoked inhibition was substantially stronger than L2/3 excitation and L1 inhibition (Fig. S1). Thus, balanced feedforward excitation and inhibition from L1 likely plays a prominent role in dendritic integration of afferent input in all cell classes, but contributes weakly to spike regulation at the soma. Alternately, recurrent circuits within L2/3 provide strong, dominant inhibition that controls somatic activity.

Fig. S1.

Comparison of PSC amplitudes recorded by using different intracellular solutions. (A) Recordings from sPCs. (A1) EPSC amplitudes recorded in K+-gluconate (filled triangles, n = 8) and Cs-gluconate (open triangles, n = 5) in response to LOT stimulation of increasing intensity. (A2) IPSC amplitudes recorded in K+-gluconate (solid circles, n = 8) and Cs-gluconate (open circles, n = 5) for LOT stimulation. (A3) EPSCs and IPSCs recorded in Cs-gluconate are balanced during LOT stimulation. (A4) EPSC and IPSCs recorded in response to L2/3 stimulation with increasing intensity (symbols are as in A1 and A2). Inhibition dominates excitation in both solutions. (B) Recordings from dPCs (description as in A). Sample sizes were n = 4 (Cs+) and n = 5 (K+) for LOT stimulation and n = 4 (Cs+) and n = 10 (K+) for L2/3 stimulation. In both sPCs and dPCs, PSC amplitudes did not significantly differ between K-gluconate and Cs-gluconate solutions. P = 0.21–0.52; Mann–Whitney u test. Mean ± SE.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated inhibition onto three classes of principal neurons in the APC—SLCs, sPCs, and dPCs. We present three main findings. First, afferent excitation is balanced by feedforward inhibition from L1 interneurons. Second, recurrent inhibition from L2/3 interneurons dominates intracortical excitation in all cell classes. Finally, SLCs, sPCs, and dPCs differ in their recruitment and inhibition and by afferent vs. recurrent circuits. These findings have important implications for the interpretation of previous studies and, ultimately, cortical processing of olfactory information.

Afferent vs. Intracortical Recruitment in Different Principal Neuron Classes.

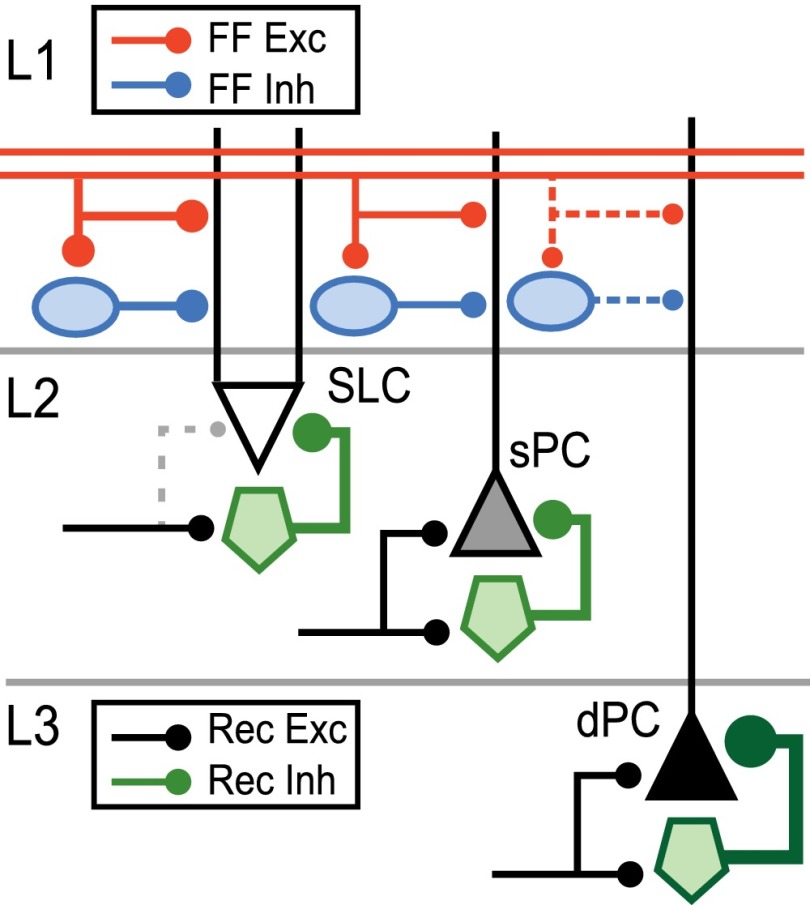

In Fig. 4, we schematize the differential recruitment and inhibition of principal neurons by afferent vs. recurrent pathways. We, and others, have found that SLCs have the lowest thresholds for afferent recruitment and strong EPSCs that depress during ongoing stimulation (36, 39, 41). SLCs did not receive recurrent excitation (dashed lines, Fig. 4) from L2/3. This finding is consistent with a lack of basal dendrites (Fig. 1) and synapses (34) in regions corresponding to intracortical projections (L1b, L2/3) as well as the fact that SLCs do not excite each other (42). Conversely, sPCs and dPCs have higher thresholds for afferent excitation, EPSCs that facilitate and receive intracortical excitation (36, 39, 41). However, in contrast to SLCs and sPCs, one-third of dPCs did not receive afferent input (dashed lines, Fig. 4). It is possible that longer dendrites in dPCs filter afferent EPSCs and IPSCs to undetectable levels when recorded at the soma. However, this possibility also implies that substantial afferent input alone—or in combination with intracortical drive—is required for L1 inputs to affect somatic responses in dPCs. Alternatively, current source density analyses show that L3 responds to afferent drive with considerable delay (43), suggestive of dominant disynaptic intracortical activity. In all classes, feedforward inhibition is weak, but balanced with respect to afferent excitation. In addition, all classes receive recurrent inhibition, although SLCs and sPCs receive significantly less recurrent inhibition than dPCs. All together, these results suggest that SLCs and sPC play sequential roles in afferent processing of olfactory bulb input (36), but support a more prominent role for dPCs in intracortical and feedback processing (37).

Fig. 4.

Feedforward and recurrent circuits in APC principal neurons. The results of this study are summarized schematically. Afferent inputs from the olfactory bulb arrive via the LOTs in L1a. Feedforward excitation (red) and disynaptic inhibition via L1 interneurons (blue) is weak and balanced in SLCs (white inverted triangle) and sPCs (gray triangle). Feedforward inputs to dPCs (black triangle) were rare and weak (dashed lines). Recurrent inhibition mediated by L2/3 interneurons (green) is significantly stronger than recurrent excitation (black) in all cell classes. SLCs did not receive L2/3 excitation in the present study (dashed). dPCs received the strongest recurrent inhibition from L2/3 (thick green line).

Feedforward Inhibition.

There have been conflicting descriptions of the contributions of feedforward and recurrent inhibition to odor processing (3, 24, 27, 28, 32). For example, it has been suggested that feedforward inhibition is broadly tuned in vivo (3). However, in vitro studies suggest that SLCs receive feedforward inhibition (24), whereas PCs receive mainly recurrent inhibition (27, 28). These discrepancies likely arise because each study focused on a different cell class and used different stimulation regimes. By selectively activating interneurons with light in the absence of afferent excitation, we find that all principal neuron classes are inhibited by L1 interneurons. Using weak LOT stimulation, we find short latency and feedforward inhibition in all cell classes. Because feedforward inhibition is significantly weaker than that from L2/3 interneurons for both optogenetic and electrical stimulation, it is conceivable that feedforward inhibition is obscured by recurrent inhibition in strong stimulation regimes of previous studies. A key finding of our study is that afferent excitation and feedforward inhibition are balanced in principal neurons. This finding contrasts with in vivo recordings that show selective, odor-evoked excitation, but broadly tuned inhibition (3). It is possible that weak LOT stimulation evokes subthreshold EPSCs and IPSCs that are balanced, but not apparent in stronger, odor-evoked responses that recruit recurrent circuits (4, 27, 28). In vivo recordings may also include deep pyramidal neurons, which we find receive less reliable LOT input, but robust broadly tuned, recurrent inhibition. Finally, our results do not preclude the interpretation that feedforward inhibition is broadly tuned, but the relationship to excitation could vary with stimulation regime.

Nonetheless, feedforward inhibition likely plays an important role in dendritic integration. Here we show that, at low stimulus intensities, feedforward inhibition is weak and balances afferent excitation. This finding suggests that sparse, subthreshold excitatory inputs could be effectively modulated by balanced feedforward inhibition. However, because feedforward inhibition is delayed and depresses with bursts of input (28), these circuit parameters may also permit supralinear responses at intermediate levels of excitation (12, 13), provided they are subthreshold for recruiting dominant feedback/recurrent inhibition (24, 27, 28). For example, short-term facilitation of afferent excitation by presynaptic bursts (39, 41) or increases in the number or correlation of olfactory bulb inputs (44) could outpace feedforward inhibition and enhance cortical responses to weak, but potentially relevant, olfactory stimuli.

Recurrent Inhibition.

Odor-driven synaptic responses suggest that recurrent excitation of PCs is stronger and more broadly tuned than afferent drive (3, 4). Likewise, we find that optogenetic and electrical stimulation of recurrent circuits provides significantly stronger inhibition to all principal neuron classes than feedforward circuits. We also find recurrent inhibition is substantially stronger than excitation in all cell classes. Similar results have been shown for L2 PCs in APC (45). Importantly, although inhibition is dominant, it covaries with excitation in PCs (45). Both PCs and interneurons in L2/3 are driven by local and long-range intracortical excitation (20, 45). In turn, L2/3 interneurons provide feedback and recurrent inhibition to SLCs and PCs (24, 27). Thus, strong inhibition from L2/3 serves two important roles: (i) feedback inhibition that further limits afferent and intracortical integration windows (24, 27, 32); and (ii) stabilization of the recurrent excitatory network (45). In the former case, SLCs provide excitatory drive to fast-spiking interneurons (24), which provide delayed feedback inhibition to SLCs and sPCs (24, 27, 28). In the latter case, odors evoke strong, broadly tuned intracortical excitation (4). The recruitment of strong feedback inhibition under these conditions could function to prevent runaway excitation and stabilize the network, resulting in sublinear or normalization of cortical responses (15, 45). Consistent with this idea, disinhibition of the piriform cortex leads to epileptic activity (46–49). All together, these feedforward and recurrent circuit features likely promote sparse responses (50–54) and low correlations (8, 11, 51) during odor processing.

Summary.

The ability to separate afferent and recurrent inhibitory circuits in piriform cortex provides insight into the relative contributions of these circuits to neural responses. Here we show that, at low stimulus intensities, feedforward inhibition balances afferent excitation. Higher stimulation intensities likely recruit intracortical excitation and, ultimately, dominant L2/3 recurrent inhibition. These circuit features are consistent with balanced and inhibition stabilized network models (12, 13, 15) that replicate supralinear and sublinear computations in visual and auditory cortex (5, 7). Thus, feedforward and recurrent inhibition in the piriform cortex could represent global mechanisms for sensory processing throughout the brain.

Methods

Slice Preparation.

Brain slices of APC were prepared from transgenic vGAT-ChR2 mice that express ChR2 and yellow fluorescent protein in interneurons under the promoter for vesicular GABA transporter (33) (Jax mice; Jackson Laboratories). ChR2(−) littermates were used in electrical stimulation paradigms. Experimental animals (P18-30) were of either sex. All surgical procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. The brain was removed from the skull and immersed in ice-cold oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.0 MgCl2, 25 dextrose, and 2.5 CaCl2; all chemicals were from Sigma unless otherwise stated). Parasagittal slices (300 μm) were made by using a vibratome (Leica Biosystems) in ice-cold ACSF. The slices were transferred to warm ACSF (37 °C) for 30 min and then rested at 20–22 °C for 1 h before recording (31–35 °C).

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell, voltage, and current-clamp recordings were performed by using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Data were low-pass-filtered (4 kHz) and digitized at 10 kHz by using an ITC-18 (Instrutech) controlled by custom software (Recording Artist, Ozymandian Industries) written in IgorPro (Wavemetrics). Recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.5 mm, outer diameter) on a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments) to a resistance of 4–12 MΩ (mean 6.4 MΩ). The series resistance was 10–22 MΩ and was not corrected. The intracellular solution consisted of 130 mM K-gluconate, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP⋅Mg, 0.3 mM GTP, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 4.5 µM QX-314, and 0.05% biocytin. In a small number of cells (n = 11) a Cs-gluconate internal solution was used to enhance the dendritic clamp (100 mM gluconic acid, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 40 mM Hepes, 2 mM ATP⋅Mg, 0.3 mM GTP, QX-314, and 0.05% biocytin, titrated to pH 7.2 with Cs-OH). Recordings were obtained from L2 principal neurons—SLCs and sPCs as well as dPCs in L3. Neurons were visualized by using infrared-differential interference contrast microscopy (Olympus). Cell classes were confirmed by using intrinsic properties and post hoc anatomical reconstruction (Neurolucida; ∼85% of reported neurons were recovered; Fig. 1A). The input resistance (Rn) and time constant (τm), of the neurons were assessed in current clamp by using a series of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current steps (−50 to 800 pA, 1-s duration). SLCs had significantly higher Rn (403 ± 30 MΩ; P < 0.01) and τm (31 ± 3 ms; P < 0.05) than sPCs (206 ± 29 MΩ; 21 ± 2 ms) and dPCs (145 ± 11 MΩ; 19 ± 2 ms). L2 and L3 PCs did not differ in Rn or τm. Resting membrane potentials (Vm) did not differ between classes (SL: 71 ± 2 mV; sPCs: 71 ± 2 mV; dPCs: −73 ± 2 mV). With respect to interneurons, FS and RS cells differed in τm (FS: 7 ± 0.5 ms; RS: 13 ± 2 ms, P = 0.004) and Sag (FS: 0.5 ± 0.1 mV; RS: 2.0 ± 0.5 mV; P = 0.01). Although Rn (FS: 125 ± 14 MΩ; RS: 129 ± 14 MΩ, P = 0.83), Vm (FS: −72 ± 2 mV; RS: −65 ± 3 mV; P = 0.09), rheobase (FS: 158 ± 23 pA; RS: 92 ± 20 pA; P = 0.06) and max firing rates (FS: 190 ± 30 Hz; RS: 130 ± 9 Hz; P = 0.09) did not differ between FS and RS cells, these values were consistent with FS and RS classifications in previous studies (20, 22).

Light Stimulation.

Blue light (λ = 460–488 nm; GFP block; Olympus) for optical stimulation was provided by metal halide lamp (200 W; Prior Scientific) passed through the microscope objective (60×, immersion; Olympus). The light spot was restricted to a ∼70-µm diameter (0.5 mW) by using the minimum aperture. To obtain the spatial profile of inhibition, interneurons were focally activated in a 5 × 4 grid pattern, whereas IPSCs were recorded in SLCs or sPCs (L2) or dPCs (superficial L3). The horizontal axis of the grid was centered on the recorded neuron, with stimulation sites ranging from −300 µm (rostral) to +300 µm (caudal) at 150-µm increments. The vertical axis ranged L1 to L3 in 125-µm increments corresponding to different lamina. Each grid site was stimulated with two light pulses (20-ms duration, 100-ms interpulse interval, 15 s between trials). Light pulses were delivered using a mechanical shutter (Sutter Instruments). The 20-ms duration was chosen to reliably evoke least one spike, and rarely two spikes, in response to a single pulse of direct somatic stimulation by using the 70-µm spot at 0.5 mW (Fig. 1). Grids were repeated three to five times per neuron, and each grid site was stimulated once every 6 min.

Electrical Stimulation.

Electrical stimulation of the LOT and L2/3 border was delivered through concentric bipolar electrodes (FHC). Electrodes were placed at a distance of 300–400 µm on the rostral (LOT) and caudal (L2/3) sides of the recorded cells. Evoked PSCs were recorded in principal neurons that were alternately held at the measured reversal potential for excitation, 0 to +10 mV (IPSCs), and at the measured reversal potential for inhibition, −40 to −50 mV (EPSCs). Under these conditions, the driving forces for excitation and inhibition were approximately matched (50 V). Stimuli consisted of single pulses (100 µs) delivered from a stimulus isolation unit (AMPI). The initial stimulation intensity was set for each neuron as the minimum required to evoke a PSC (2–7 V). Stimulus intensity was then increased in 1V increments up to +5V.

Analysis.

Electrophysiology traces are presented as the average across trials for individual neurons. Analyses across neurons are presented as the mean ± SE. For optogenetic stimulation, IPSC strength was taken as the area (pA⋅s) under the first IPSC. Comparisons of EPSC and IPSC strength were based on peak amplitude within 10 ms of PSC onset. Average PSCs with minimum amplitude of 10 pA were included for analyses; smaller PSCs were not distinguishable from noise (∼5–10 pA).

Statistics.

Unless otherwise stated, all statistical comparisons were made by using paired and unpaired Student’s t tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons as needed. Pearson’s correlation was used to for significance of linear fits.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Urban and B. Doiron for helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01 DC015139 (to A.-M.M.O.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1519295113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72(2):231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabernet L, Jadhav SP, Feldman DE, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;48(2):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poo C, Isaacson JS. Odor representations in olfactory cortex: “Sparse” coding, global inhibition, and oscillations. Neuron. 2009;62(6):850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poo C, Isaacson JS. A major role for intracortical circuits in the strength and tuning of odor-evoked excitation in olfactory cortex. Neuron. 2011;72(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schummers J, Sharma J, Sur M. Bottom-up and top-down dynamics in visual cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2005;149:65–81. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)49006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W, Carrasquillo Y, Hooks BM, Nerbonne JM, Burkhalter A. Distinct balance of excitation and inhibition in an interareal feedforward and feedback circuit of mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33(44):17373–17384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2515-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, et al. Imbalance of excitation and inhibition at threshold level in the auditory cortex. Front Neural Circuits. 2015;9:11. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2015.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graupner M, Reyes AD. Synaptic input correlations leading to membrane potential decorrelation of spontaneous activity in cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33(38):15075–15085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0347-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansel D, van Vreeswijk C. The mechanism of orientation selectivity in primary visual cortex without a functional map. J Neurosci. 2012;32(12):4049–4064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6284-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litwin-Kumar A, Doiron B. Slow dynamics and high variability in balanced cortical networks with clustered connections. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(11):1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nn.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litwin-Kumar A, Oswald AM, Urban NN, Doiron B. Balanced synaptic input shapes the correlation between neural spike trains. PLOS Comput Biol. 2011;7(12):e1002305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy BK, Miller KD. Balanced amplification: A new mechanism of selective amplification of neural activity patterns. Neuron. 2009;61(4):635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozeki H, Finn IM, Schaffer ES, Miller KD, Ferster D. Inhibitory stabilization of the cortical network underlies visual surround suppression. Neuron. 2009;62(4):578–592. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pehlevan C, Sompolinsky H. Selectivity and sparseness in randomly connected balanced networks. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin DB, Van Hooser SD, Miller KD. The stabilized supralinear network: A unifying circuit motif underlying multi-input integration in sensory cortex. Neuron. 2015;85(2):402–417. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neske GT, Patrick SL, Connors BW. Contributions of diverse excitatory and inhibitory neurons to recurrent network activity in cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2015;35(3):1089–1105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter JT, et al. Selective excitation of subtypes of neocortical interneurons by nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19(13):5228–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swadlow HA. Fast-spike interneurons and feedforward inhibition in awake sensory neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(1):25–32. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavrilovici C, D’Alfonso S, Poulter MO. Diverse interneuron populations have highly specific interconnectivity in the rat piriform cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(9):1570–1588. doi: 10.1002/cne.22291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Distinctive classes of GABAergic interneurons provide layer-specific phasic inhibition in the anterior piriform cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(12):2971–2984. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Inhibitory neurons in the anterior piriform cortex of the mouse: Classification using molecular markers. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(10):1670–1687. doi: 10.1002/cne.22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young A, Sun QQ. GABAergic inhibitory interneurons in the posterior piriform cortex of the GAD67-GFP mouse. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(12):3011–3029. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haberly LB, Price JL. The axonal projection patterns of the mitral and tufted cells of the olfactory bulb in the rat. Brain Res. 1977;129(1):152–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Microcircuits mediating feedforward and feedback synaptic inhibition in the piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32(3):919–931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haberly LB, Price JL. Association and commissural fiber systems of the olfactory cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1978;178(4):711–740. doi: 10.1002/cne.901780408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DM, Illig KR, Behan M, Haberly LB. New features of connectivity in piriform cortex visualized by intracellular injection of pyramidal cells suggest that “primary” olfactory cortex functions like “association” cortex in other sensory systems. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6974–6982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheridan DC, et al. Matching of feedback inhibition with excitation ensures fidelity of information flow in the anterior piriform cortex. Neuroscience. 2014;275:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stokes CC, Isaacson JS. From dendrite to soma: Dynamic routing of inhibition by complementary interneuron microcircuits in olfactory cortex. Neuron. 2010;67(3):452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapur A, Pearce RA, Lytton WW, Haberly LB. GABAA-mediated IPSCs in piriform cortex have fast and slow components with different properties and locations on pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78(5):2531–2545. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biedenbach MA, Stevens CF. Intracellular postsynaptic potentials and location of synapses in pyramidal cells of the cat olfactory cortex. Nature. 1966;212(5060):361–362. doi: 10.1038/212361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biedenbach MA, Stevens CF. Synaptic organization of cat olfactory cortex as revealed by intracellular recording. J Neurophysiol. 1969;32(2):204–214. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luna VM, Schoppa NE. GABAergic circuits control input-spike coupling in the piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28(35):8851–8859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2385-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao S, et al. Cell type–specific channelrhodopsin-2 transgenic mice for optogenetic dissection of neural circuitry function. Nat Methods. 2011;8(9):745–752. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haberly L, Behan M. Structure of the piriform cortex of the opossum. III. Ultrastructural characterization of synaptic terminals of association and olfactory bulb afferent fibers. J Comp Neurol. 1983;219(4):448–460. doi: 10.1002/cne.902190406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagiwara A, Pal SK, Sato TF, Wienisch M, Murthy VN. Optophysiological analysis of associational circuits in the olfactory cortex. Front Neural Circuits. 2012;6:18. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Two layers of synaptic processing by principal neurons in piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2156–2166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5430-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiegand HF, et al. Complementary sensory and associative microcircuitry in primary olfactory cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31(34):12149–12158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0285-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luna VM, Pettit DL. Asymmetric rostro-caudal inhibition in the primary olfactory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(5):533–535. doi: 10.1038/nn.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oswald AM, Urban NN. Interactions between behaviorally relevant rhythms and synaptic plasticity alter coding in the piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6092–6104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6285-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bathellier B, Margrie TW, Larkum ME. Properties of piriform cortex pyramidal cell dendrites: Implications for olfactory circuit design. J Neurosci. 2009;29(40):12641–12652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Neural coding by two classes of principal cells in the mouse piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26(46):11938–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3473-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choy JM, et al. Optogenetic mapping of intracortical circuits originating from semilunar cells in piriform cortex. Cereb Cortex. October 26, 2015 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ketchum KL, Haberly LB. Membrane currents evoked by afferent fiber stimulation in rat piriform cortex. II. Analysis with a system model. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69(1):261–281. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davison IG, Ehlers MD. Neural circuit mechanisms for pattern detection and feature combination in olfactory cortex. Neuron. 2011;70(1):82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franks KM, et al. Recurrent circuitry dynamically shapes the activation of piriform cortex. Neuron. 2011;72(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birjandian Z, Narla C, Poulter MO. Gain control of γ frequency activation by a novel feed forward disinhibitory loop: Implications for normal and epileptic neural activity. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:183. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demir R, Haberly LB, Jackson MB. Voltage imaging of epileptiform activity in slices from rat piriform cortex: Onset and propagation. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(5):2727–2742. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demir R, Haberly LB, Jackson MB. Epileptiform discharges with in-vivo-like features in slices of rat piriform cortex with longitudinal association fibers. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86(5):2445–2460. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gavrilovici C, D’Alfonso S, Dann M, Poulter MO. Kindling-induced alterations in GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition and neurosteroid activity in the rat piriform cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(5):1373–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCollum J, et al. Short-latency single unit processing in olfactory cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 1991;3(3):293–299. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1991.3.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miura K, Mainen ZF, Uchida N. Odor representations in olfactory cortex: Distributed rate coding and decorrelated population activity. Neuron. 2012;74(6):1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rennaker RL, Chen CF, Ruyle AM, Sloan AM, Wilson DA. Spatial and temporal distribution of odorant-evoked activity in the piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27(7):1534–1542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4072-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stettler DD, Axel R. Representations of odor in the piriform cortex. Neuron. 2009;63(6):854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhan C, Luo M. Diverse patterns of odor representation by neurons in the anterior piriform cortex of awake mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30(49):16662–16672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4400-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]