Significance

The composition of bacterial populations in the human digestive tract is known to affect our well-being, to influence our ability to overcome diseases, and to be tightly linked with the host genotype. In contrast, the extent to which variation in the plant genotype affects the associated bacteria and, hence, plant health and productivity remains unknown, particularly of field-grown plants. Genetically modified poplars, down-regulated for cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, substantially influence the microbiome of the plant endosphere without perceptible impact on the rhizosphere microbiota. Unraveling the host genotype-dependent plant–microbe associations is crucial to comprehend the effects of engineering the plant metabolic pathway and possibly to exploit the eukaryote–prokaryote associations in phytoremediation applications, sustainable crop production, and the production of secondary metabolites.

Keywords: host genotype modulation, CCR gene silencing, plant-associated bacteria

Abstract

Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), an enzyme central to the lignin biosynthetic pathway, represents a promising biotechnological target to reduce lignin levels and to improve the commercial viability of lignocellulosic biomass. However, silencing of the CCR gene results in considerable flux changes of the general and monolignol-specific lignin pathways, ultimately leading to the accumulation of various extractable phenolic compounds in the xylem. Here, we evaluated host genotype-dependent effects of field-grown, CCR-down-regulated poplar trees (Populus tremula × Populus alba) on the bacterial rhizosphere microbiome and the endosphere microbiome, namely the microbiota present in roots, stems, and leaves. Plant-associated bacteria were isolated from all plant compartments by selective isolation and enrichment techniques with specific phenolic carbon sources (such as ferulic acid) that are up-regulated in CCR-deficient poplar trees. The bacterial microbiomes present in the endosphere were highly responsive to the CCR-deficient poplar genotype with remarkably different metabolic capacities and associated community structures compared with the WT trees. In contrast, the rhizosphere microbiome of CCR-deficient and WT poplar trees featured highly overlapping bacterial community structures and metabolic capacities. We demonstrate the host genotype modulation of the plant microbiome by minute genetic variations in the plant genome. Hence, these interactions need to be taken into consideration to understand the full consequences of plant metabolic pathway engineering and its relation with the environment and the intended genetic improvement.

The plant bacterial microbiome epitomizes the mutualistic coexistence of eukaryotic and prokaryotic life providing a plethora of reciprocal advantages and represents one of the key determinants of plant health and productivity (1, 2). However, the extent to which variation in the plant host genotype influences the associated bacterial microbiota remains virtually unexplored. In contrast, the host genotype-dependent associations that shape the human gut microbiome have been extensively characterized, whereby even variations in single host genes strongly affected the human gut microbiota (3–5). The interactions between a plant and its microbiome are highly complex and dynamic, involving multiple reciprocal signaling mechanisms and an intricate interplay between the bacteria and the plant’s innate immune system (6). Therefore, even small changes in the host genome (ecotypes, cultivars, genetically modified genotypes, etc.) may influence the plant microbiome and may even feed back to modulate the behavior and the productivity of the host plant (2, 7–9). Only a few studies have explored the host genotype modulation of bacterial microbiota. Recently, the host genotype-dependent effects of several Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes have been evaluated and have revealed a significant, but weak, host genotype-dependent impact on the selection of the Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial communities (10, 11). Furthermore, the crucial importance of the plant immune system (with a main role for salicylic acid) in the successful endophytic colonization and assemblage of a normal root microbiome has been reported (12).

Here, we examine the host genotype-dependent effects of field-grown poplar (Populus tremula × Populus alba) trees modified in their lignin biosynthesis, on the bacterial rhizosphere and endosphere microbiome, namely the microbiota present in the roots, stems, and leaves. Transgenic poplar trees were produced by silencing of the gene encoding cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), the first enzyme in the monolignol-specific branch of lignin biosynthesis (13, 14). In this manner, feedstocks with reduced recalcitrance due to decreased amounts of lignin polymers can be generated for the production of end-use products, such as second-generation biofuels (15, 16). CCR-down-regulated poplar trees grown in the greenhouse and in field trials in Belgium (Ghent) and France (Orléans) repeatedly displayed reduced lignin levels (17, 18). Simultaneously, CCR gene silencing in poplar led to the accumulation of various extractable phenolic compounds in the xylem (17). Hence, the carbon sources available for the associated microbiota differed profoundly between WT and CCR-deficient genotypes. Moreover, phenolic-related compounds, such as those accumulating in CCR-deficient trees, have been implicated in the modulation of the rhizosphere microbiome in Arabidopsis (19), underlining their potential to affect bacterial communities. Furthermore, perturbations in the lignin biosynthesis via CCR-down-regulation resulted in compositional alterations of the cell wall. Cell wall features play important roles during endophytic colonization that regulate endophytic competence (7, 8) and have been reported to serve as assembly (colonization) cues in root microbiota of Arabidopsis (10). Therefore, compositional alterations in the cell wall may cause changes in the bacterial colonization of the CCR-down-regulated trees.

We hypothesized that the poplar-associated bacteria depend on the host genotype and that the differential accumulation of compounds in the xylem of CCR-deficient poplar trees influences the metabolic capacities of the bacterial microbiome. CCR-deficient poplar trees are, except for the T-DNA construct, isogenic with the WT poplar trees, making them prime candidates to investigate the host genotype impact and the direct causality of the CCR gene silencing on the plant-associated bacterial communities.

Results and Discussion

Collection and Processing of Samples.

WT and CCR-deficient (CCR–) field-grown poplar (P. tremula × P. alba cv. ‘717–1-B4’) trees (15) were sampled in October 2011. The sampled poplar trees were part of a field trial planted (May 2009) in a randomized block design (density = 15,000 trees per ha, interplant distance = 0.75 m) (18, 20). The samples were collected from four compartments (number of individual trees sampled: nWT = 12 and nCCR– = 12): rhizosphere soil (strictly defined as soil particles attached to the roots) and root, stem, and leaf compartments defined as plant tissues depleted of soil particles and epiphytic bacteria by sequential washing.

Nonselective and Selective Isolation of Bacterial Cells.

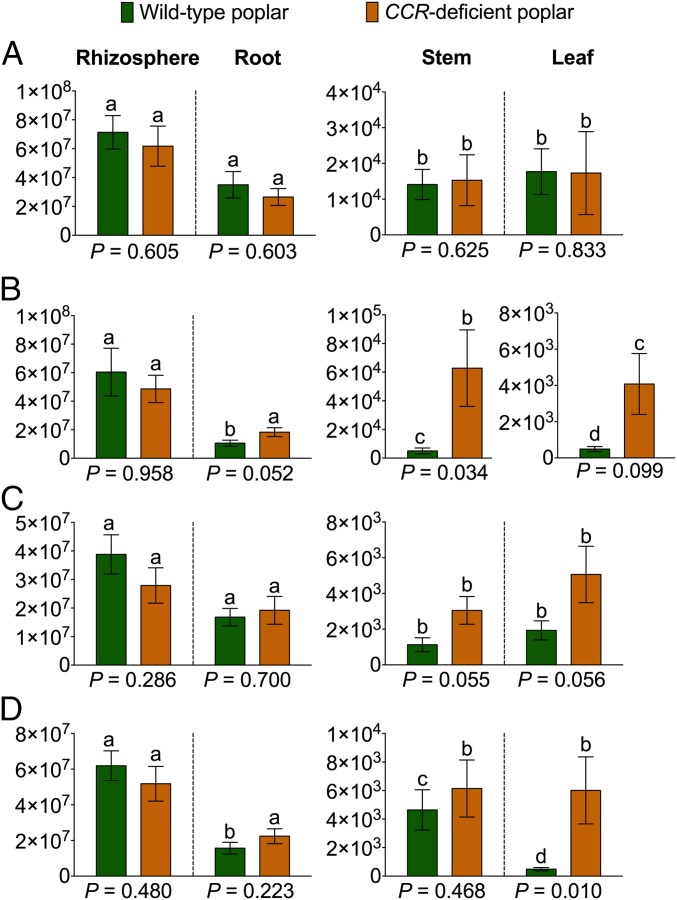

First, to compare the total number of bacterial cells, we isolated them from the rhizosphere soil and surface-sterilized plant compartments of WT and CCR– poplar trees with a nonselective approach on nutrient medium (Fig. 1A). Bacterial cell counts (cfus per g) were highly comparable between WT and CCR– poplars across all compartments, indicating that the CCR gene silencing had no major effect on the rhizospheric and endophytic colonizations and on the stable establishment of bacterial communities. Furthermore, within each genotype, the abundance of the bacterial cells (cfus per g) consistently decreased from the rhizosphere soil over the root to the stem, implying a normal colonization pattern of plant-associated bacteria (7). Soil-residing bacteria initially colonize the rhizosphere and rhizoplane, largely driven by chemoattraction to rhizodeposits (carbohydrates, amino acids, root cap border cells, etc.) that are released into the root zone by the host plant (8, 21–23). Following rhizosphere and rhizoplane colonization, only certain soil-borne bacteria can, through passive or active mechanisms, cross physical barriers (such as endodermis and pericycle) to reach the xylem vessels and further colonize the roots, stems, and leaves (8, 23). The bacterial cell count was slightly (not significantly) higher in the leaves than in the stems, most probably attributable to endophytic colonization via the stomata (Fig. 1A) (23, 24).

Fig. 1.

Bacterial cell counts (abundance) expressed as cfus per gram of soil (rhizosphere soil) or per gram of fresh plant tissue (root, stem, and leaf). (A) Nonselective isolation of bacterial cells from different compartments for both genotypes. (B–D) Selective isolation of bacterial cells with ferulic acid (B), sinapic acid (C), and p-coumaric (D) acid as sole carbon source. cfus are averages of at least eight replicates ± SE. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between the different plant compartments within each genotype are indicated with lowercase letters. P values of pairwise comparisons between WT and CCR– poplars within each compartment are given below each graph.

To link the influence of the CCR gene silencing and resulting changes in the poplar xylem composition with modifications in the metabolic capacities of the bacterial communities, we selectively isolated bacterial cells from all four compartments (WT and CCR– trees) by using specific phenylpropanoids (ferulic acid, sinapic acid, and p-coumaric acid) as sole carbon sources in the nutrient medium (Fig. 1 B–D). Ferulic and sinapic acids, and derivatives thereof, had previously been shown to be up-regulated in the CCR– poplar (17) and ferulic acid to be even incorporated into the lignin polymer (17, 18, 25). In contrast to the nonselective approach, the bacterial cell counts were higher in CCR– poplar than those in the WT. Differences in bacterial cell counts between genotypes were exclusively found inside the plant (root, stem, and leaf). In the rhizosphere soil, pairwise comparison of bacterial cell counts between genotypes revealed highly comparable bacterial abundances across the various phenolic carbon sources, indicating that the host genotype has a profound effect on the metabolic capacities present in the endophytic communities. The capacity to degrade specific phenolic carbon sources was clearly enhanced in the endosphere of the CCR– poplar. Interestingly, the most pronounced differences occurred with ferulic acid as sole carbon source, of which increased levels had previously been identified in CCR-deficient genotypes (17).

Selective Enrichment of Bacterial Cells: Cell Counts.

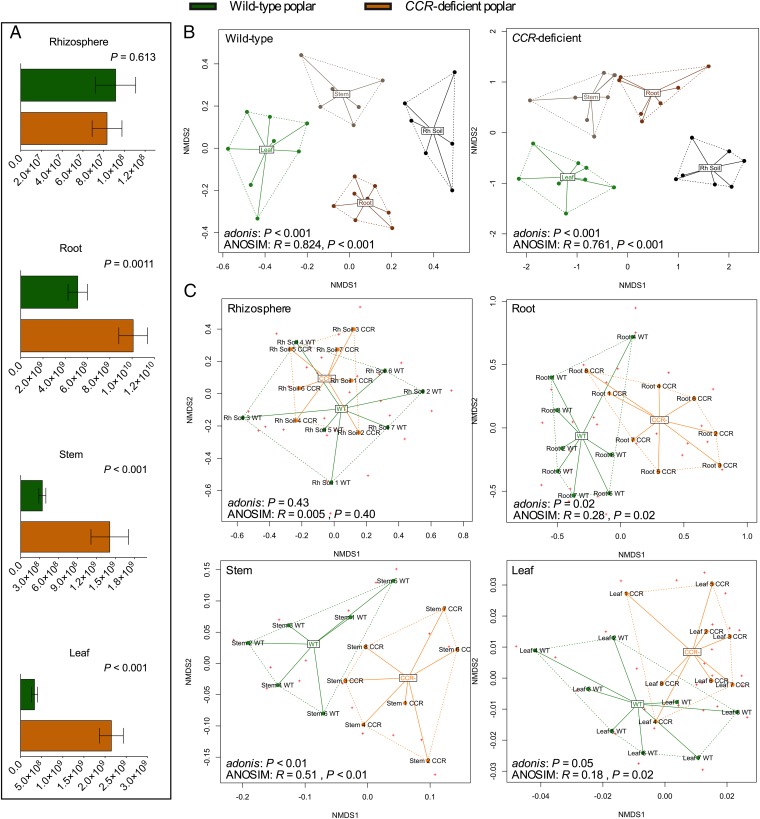

Further, we selectively enriched bacterial cells (ferulic acid as carbon source, 36 d of incubation) from the rhizosphere soil and surface-sterilized plant tissues of WT and CCR– poplar. We determined bacterial cell counts (cfus per g) (Fig. 2A) as well as the bacterial community structures (16S rRNA Sanger sequencing) (Fig. S1). In accordance with the selective isolation from the rhizosphere soil, highly similar numbers of bacterial cells (cfus per g ± SD) were obtained from the CCR– poplars (8.33 × 107 ± 1.44 × 107) compared with the WT (9.16 × 107 ± 1.93 × 107) (P = 0.613), but bacterial abundances inside roots (P = 0.0011), stems (P < 0.001), and leaves (P < 0.001) of CCR– trees were consistently higher (Fig. 2A). Again, this result indicates that CCR gene silencing and the ensuing changes in xylem composition drive the metabolic abilities present in the endosphere toward an increased degradation potential for specific phenolics. Further, we observed considerably more variation in the bacterial cell counts from the CCR– trees than in those from the WT (Fig. 2A). This discrepancy can be attributed to variation among the genotypes in the levels of gene silencing that are reflected by different intensities of the red-brown xylem coloration associated with CCR down-regulation and the related variation in the xylem composition (17, 18), thereby potentially influencing the plant-associated bacterial community.

Fig. 2.

Selective enrichment of bacterial cells from each compartment and genotype with ferulic acid as sole carbon source. (A) Bacterial cell counts expressed as cfus per gram of soil (rhizosphere soil) or per gram of fresh plant tissue (root, stem, and leaf). P values of pairwise comparisons between WT and CCR– poplars within each plant compartment are indicated on the graphs. (B) NMDS with Bray–Curtis distances of square-root-transformed OTU abundance data of bacterial communities isolated from each plant compartment within both genotypes. (C) NMDS analyses of pairwise comparisons between WT and CCR– poplar trees within each compartment (rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf). NMDS analyses contain at least six replicates per plant compartment. Statistical support for the NMDS clustering is provided by the permutation-based hypothesis test analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (adonis). Results from both hypothesis tests are indicated below each graph.

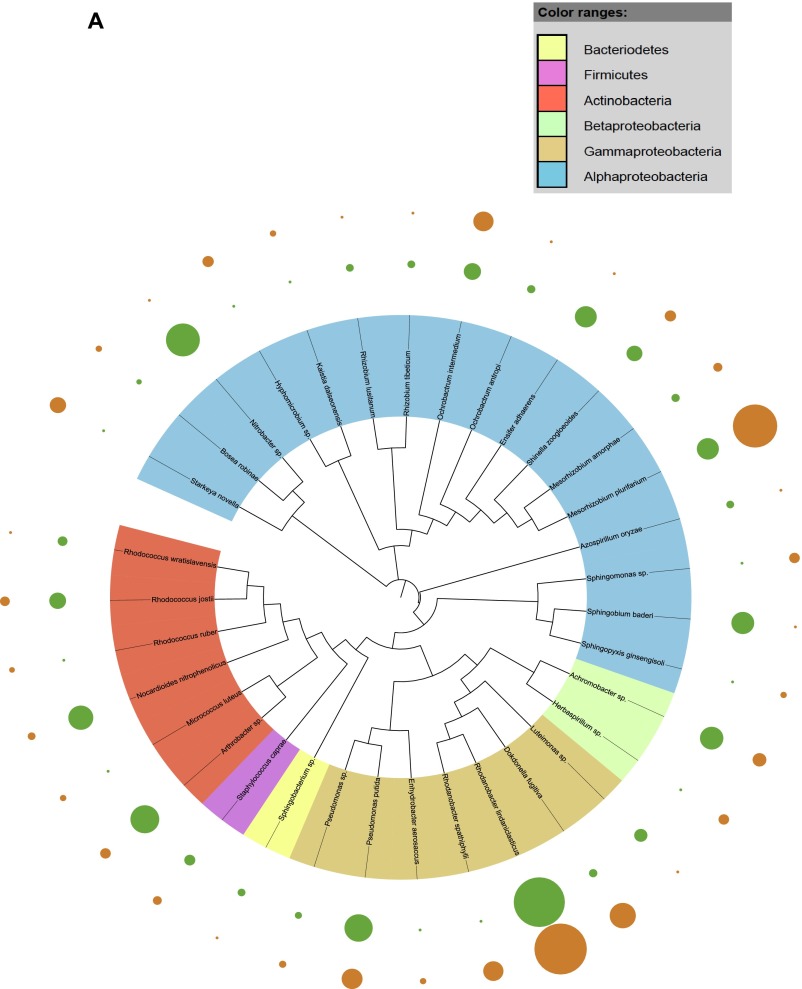

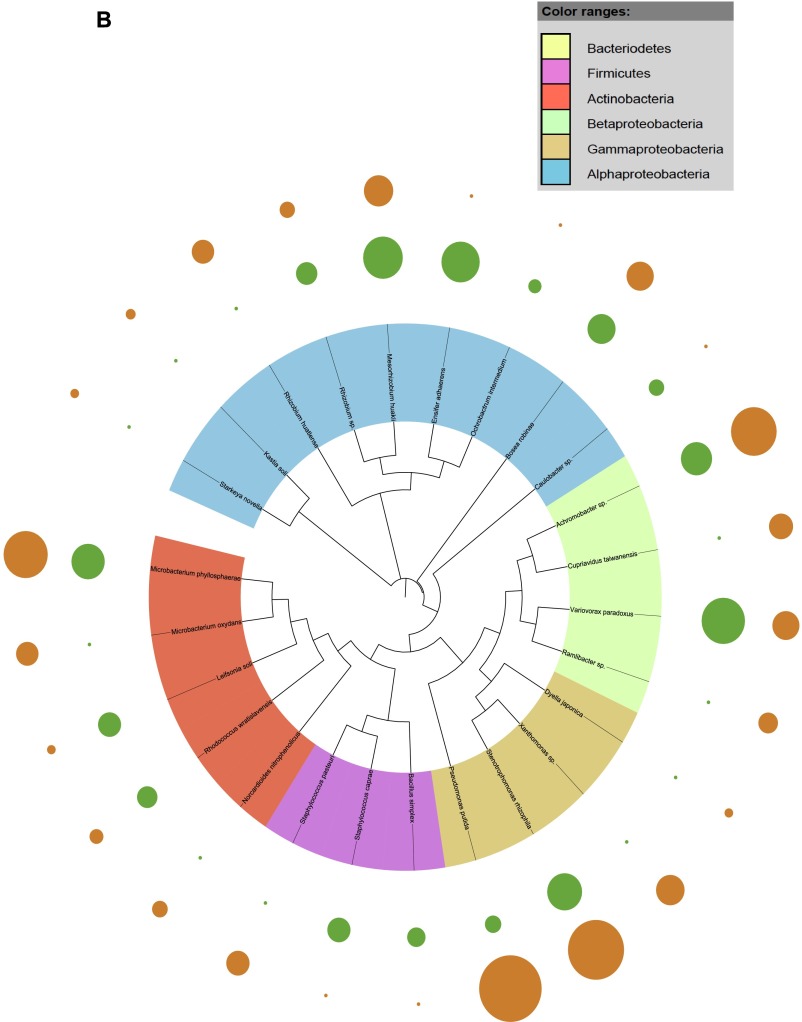

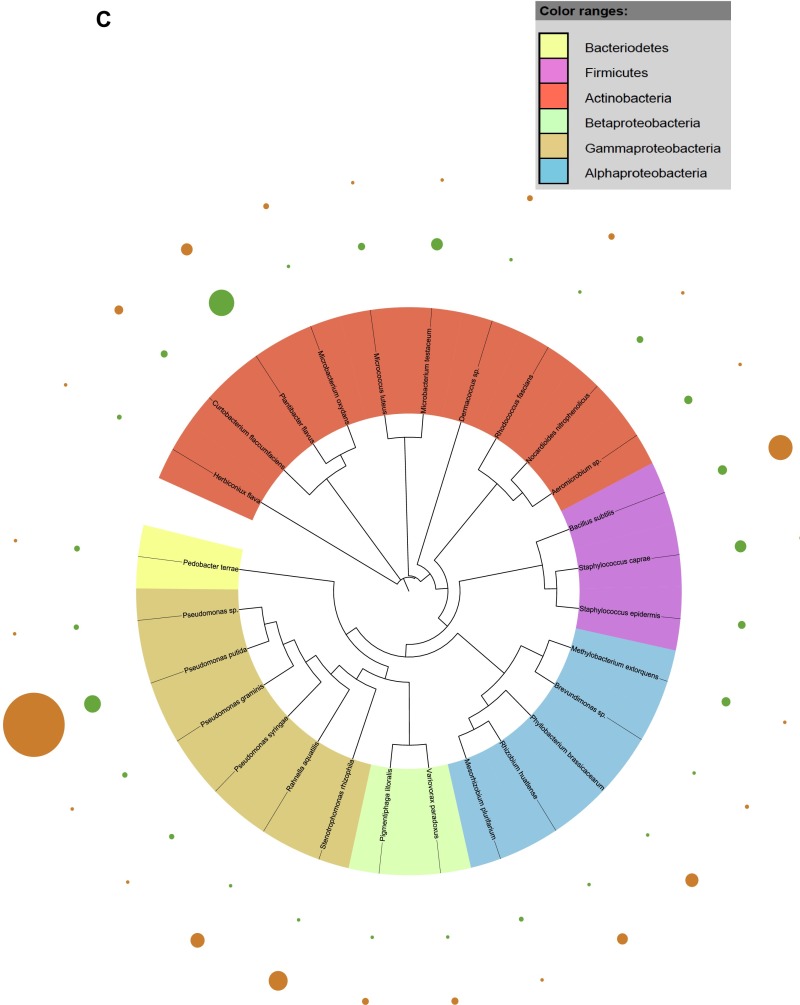

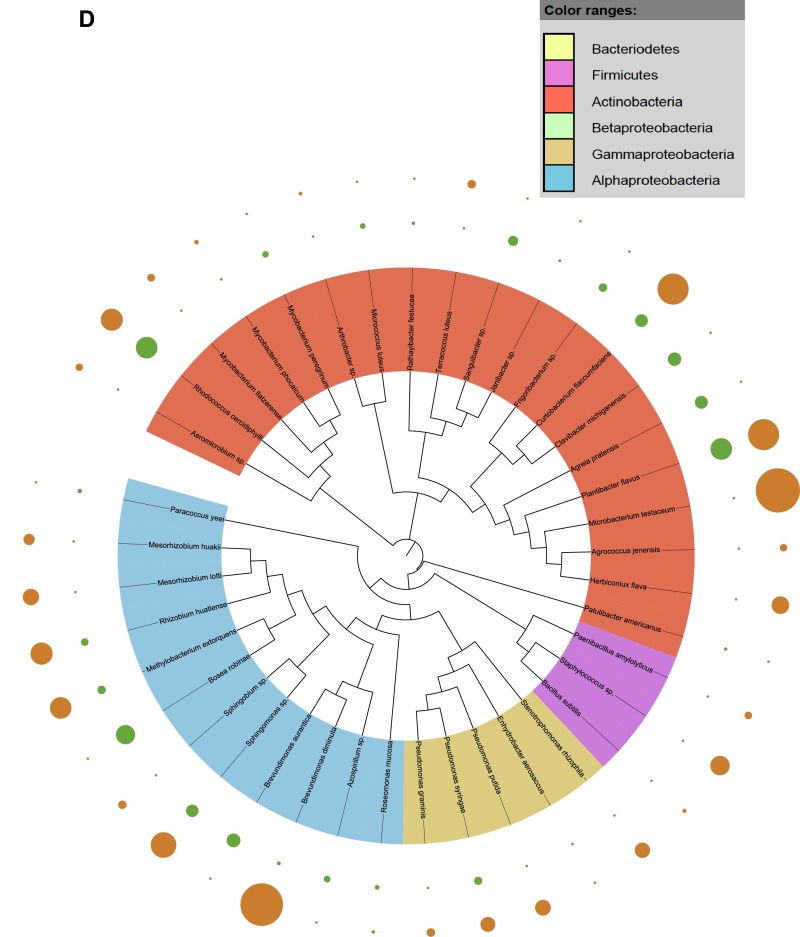

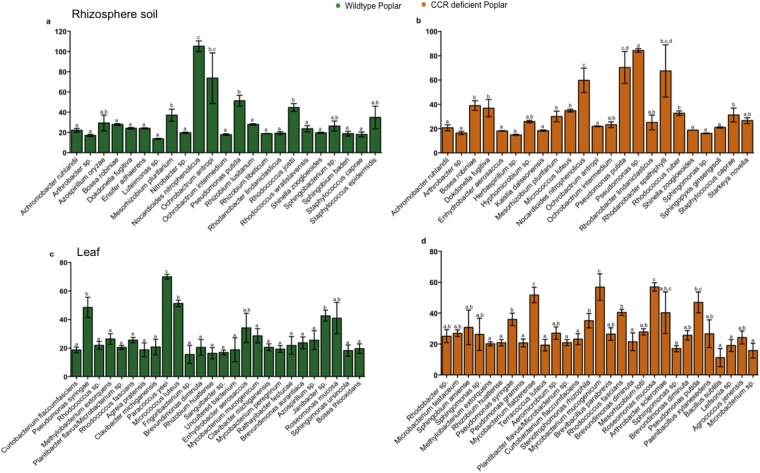

Fig. S1.

Taxonomic dendograms of all bacterial species. (A) Isolated from the rhizosphere soil of WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. (B) Isolated from the root tissues of WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. (C) Isolated from the stem tissues of WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. (D) Isolated from the leaf tissues of WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. Color ranges identify phyla within the tree. Diameters of the circles represent the square-root transformed abundance data of the corresponding species in the overall community community (green and orange, WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees, respectively). Taxonomic dendrograms were generated with Unipro UGENE and displayed with Itol (44).

Selective Enrichment of Bacterial Cells: Species Composition.

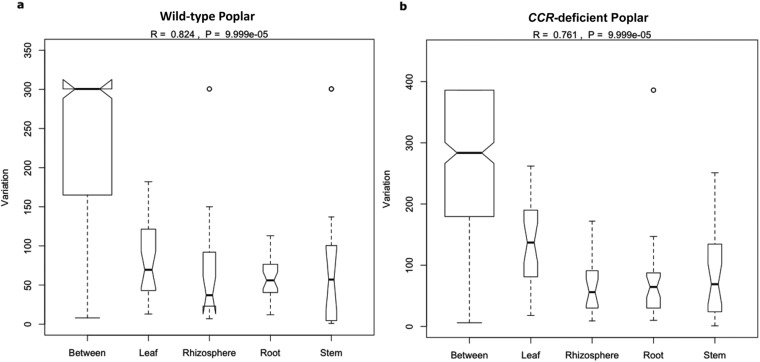

To compare species composition within the different sampled compartments and genotypes, we grouped all isolated bacterial strains based on their morphology to create provisional operational taxonomic units (OTUs) that were validated with full-length 16S-rRNA Sanger sequencing and we determined abundance data (cell counts) for each bacterial OTU. The OTU abundance data were square-root-transformed and similarities were displayed with nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) with Bray–Curtis distances (26, 27) (SI Materials and Methods). For both genotypes, NMDS analyses revealed strong clustering of the bacterial communities according to the different compartments (rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf) (Fig. 2B). To statistically support the visual clustering of the bacterial communities in the NMDS analyses, we compared the different compartments by means of permutation-based hypothesis tests: analysis of similarities (ANOSIM), an analog of univariate ANOVA, and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (adonis) (SI Materials and Methods). All compartments rendered microbiota significantly dissimilar from each other (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). Each plant compartment represents a unique ecological niche with specific available nutrients (10), an active systemic colonization originating from the rhizosphere, and a resulting endophytic competence limited to specific strains (7). Microbiome niche differentiation at the rhizosphere soil–root interface has been reported previously (10, 28–30).

Fig. S2.

Graphical representation of the analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) of a priori defined groups (rhizosphere, root, stem, and leaf) within each host genotype. (A) Wild-type poplar. (B) CCR– poplar. Variation of each a priori defined group is compared with the “between” variation that represents the observed variation between the different groups. R values and P values are depicted on top of each graph. Box plots display the first (25%) and third (75%) quartile and the median (bold line), maximum, and minimum observed values (without outliers). Outliers (more or less than 3/2 of the upper/lower quartile) are displayed as open circles.

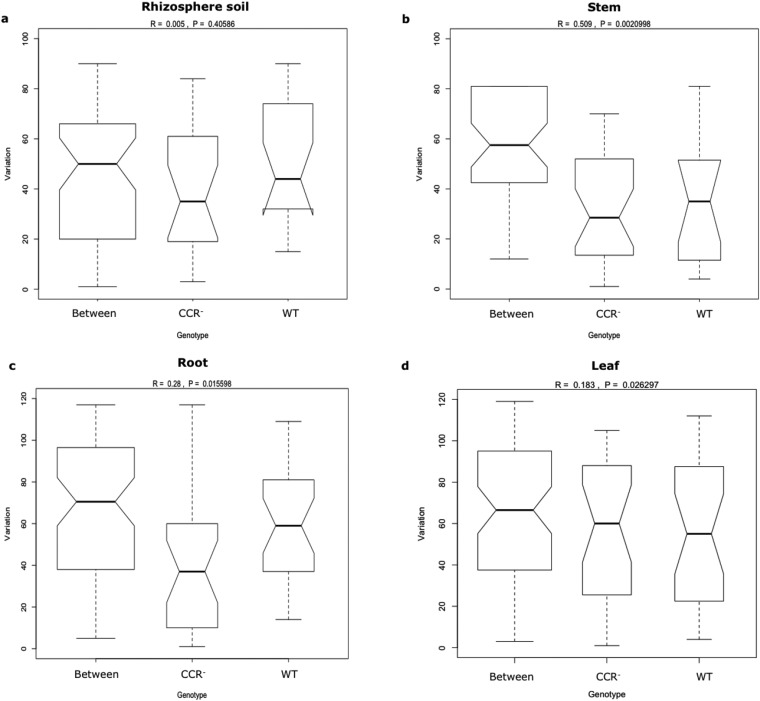

To determine the influence of the host genotype on the bacterial communities, we compared the genotypes pairwise within each compartment by means of NMDS with Bray–Curtis distances (Fig. 2C). In the rhizosphere soil, bacterial communities showed no relevant clustering according to the genotype as visually apparent by the NMDS analysis (Fig. 2C). Both ANOSIM and adonis statistically confirmed that the bacterial communities of both genotypes were highly comparable within the rhizosphere (ANOSIM: R < 0.01, P = 0.40; adonis: P = 0.43) (Fig. S3A). These data are in agreement with the report in which transgenic poplar lines modified in lignin biosynthesis normally formed ectomycorrhiza (EM) and in which variations in the EM community structure between the different transgenic poplar lines were similar to variations in commercial poplar hybrids (31). Furthermore, colonization by arbuscular mycorrhiza or other fungi was not altered in barley (Hordeum vulgare) mutants at a lignin production-influencing locus rob1 (32). However, in contrast to the rhizosphere soil, the poplar genotypes differed significantly in the endosphere. Moreover, these differences were highly consistent throughout the various plant compartments. NMDS analyses and permutation-based hypothesis tests of the bacterial communities in the roots, stems, and leaves revealed strong clustering according to the genotype (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3 B–D). The clustering according to genotype was the most pronounced in the stems, where no visual overlap between the bacterial communities was seen (ANOSIM: R = 0.51, P < 0.01; adonis: P < 0.01) (Fig. S3C). Because the lignification process is the highest in the stem xylem (13), the most distinct effects of CCR gene silencing and changes in xylem composition are expected to occur in the stems (17). Furthermore, lumen colonization of xylem vessels by bacterial endophytes has been reported as a route for bacterial dispersal to vegetative plant parts, ensuring direct contact between endophytes and nutrients available in xylem cells (7, 24). In roots and leaves, the clustering according to genotype persisted with small visual overlaps between WT and CCR– poplar trees. Pairwise statistical analyses of the genotypes in roots and leaves confirmed the significance of the visually observed differences with NMDS at the 95% significance level (Fig. S3 B and D).

Fig. S3.

Graphical representation of analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) of a priori defined groups (WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees) within each plant compartment. (A) Rhizosphere soil. (B) Stem. (C) Root. (D) Leaf. Variation of each a priori defined group is compared with the “between” variation that represents the observed variation between the different groups. R values and P values are depicted on top of each graph. Box plots display the first (25%) and third (75%) quartile and the median (bold line), maximum, and minimum observed values (without outliers). Outliers (more or less than 3/2 of the upper/lower quartile) are displayed as open circles.

Selective Enrichment of Bacterial Cells: Univariate Ecological Measures and Species–Genotype Association Analysis.

Furthermore, we calculated OTU richness (Margaleff), evenness (Shannon–Wiener), and diversity (inverse Simpson) within each compartment and genotype based on OTU abundance (Table S1). For all ecological indices, the average values were highly similar between WT and CCR– poplar trees in the rhizosphere soil. However, in the endosphere, OTU richness, evenness, and diversity were consistently lower in CCR– trees than those in the WT, except for the OTU richness in the leaves. High variation in the indices reduced the significance of the results, but borderline significant differences were found for the OTU evenness in roots (P = 0.095) and stems (P = 0.075). Pairwise comparison of the total endophytic evenness (calculated as the average of roots, stems, and leaves) between WT and CCR– poplar trees revealed a significant decrease in the total endophytic evenness (P = 0.023) of the CCR-deficient trees.

Table S1.

Univariate ecological measures of the bacterial communities based on OTU abundance with Margalef’s richness, Shannon’s evenness, and inverse Simpson diversity

| Genotype | Rhizosphere | Root | Stem | Leaf | Total endosphere |

| Margalef’s richness | |||||

| WT | 0.329 ± 0.044a | 0.248 ± 0.025a,b | 0.180 ± 0.011b,c | 0.128 ± 0.011c | 0.157 ± 0.012* |

| CCR– | 0.346 ± 0.042a | 0.195 ± 0.024b | 0.130 ± 0.038b | 0.138 ± 0.012b | 0.148 ± 0.011* |

| P value | 0.816 | 0.160 | 0.176 | 0.639 | 0.459 |

| Shannon’s evenness | |||||

| WT | 0.776 ± 0.086a | 0.664 ± 0.040a,b | 0.544 ± 0.078b,c | 0.447 ± 0.028c | 0.503 ± 0.026* |

| CCR– | 0.783 ± 0.104a | 0.560 ± 0.043b | 0.338 ± 0.086c | 0.390 ± 0.029c | 0.417 ± 0.026* |

| P value | 0.863 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.167 | 0.023 |

| Inverse Simpson diversity | |||||

| WT | 3.451 ± 0.358a | 3.860 ± 3.126a | 2.718 ± 0.249a,b | 2.239 ± 0.129b | 2.607 ± 0.160* |

| CCR– | 3.345 ± 0.420a | 3.126 ± 0.289a | 2.415 ± 0.214a,b | 2.050 ± 0.112b | 2.330 ± 0.113* |

| P value | 0.850 | 0.201 | 0.303 | 0.282 | 0.177 |

Values are averages of at least eight biological independent replicates ± SD. Indices were statistically compared with a two-way ANOVA. Significant differences between the different plant compartments within each genotype are indicated with letters (P < 0.05). P values of pairwise comparisons between host genotypes within each tissue are indicated. Significant differences between the rhizosphere and total endosphere environment (average of root, stem, and leaf samples) are indicated with an asterisk (P < 0.05).

To ascertain the bacterial species responsible for the observed community differentiation in the endosphere of poplar, we used a species–genotype association analysis. Associations were calculated with the Dufrene–Legendre indicator species analysis routine (Indval, indicator value) in R (Table S2) (27). We identified a significant association in roots (R = 0.85, P < 0.01) and stems (R = 0.98, P < 0.01) of the CCR– trees for Pseudomonas putida, which is known for its diverse metabolic capacities and adaptation to various ecological niches, including the ability to thrive in soils and sediments with high concentrations of toxic metals and complex organic contaminants (33). P. putida strains are routinely found as plant growth-promoting rhizospheric and endophytic bacteria (34, 35) and several degradation pathways have been elucidated in P. putida for lignin-derived low-molecular-weight compounds (such as the ferulate catabolic pathway) (36). The relative abundance of P. putida in roots and stems was 26.3% and 75.9%, respectively (Fig. S1 B and C). The selective pressure exerted by the host genotype, specifically changes in the accessible carbon and energy sources (up to 2.8-fold increase in soluble phenolics) in the xylem as a consequence of CCR gene silencing (17) yielded endophytic bacteria more adapted to degrade complex phenolic compounds, such as P. putida.

Table S2.

Species indicator analysis showing species significantly correlated to WT or CCR-deficient poplars within each tissue

| Plant compartment | OTU | Indicator value | P value | Relative abundance, % |

| WT poplar | ||||

| Rhizosphere | NA | — | — | — |

| Root | NA | — | — | — |

| Stem | Plantibacter flavus | 0.73 | 0.01 | 49.2 |

| Leaf | NA | — | — | — |

| CCR-deficient poplar | ||||

| Rhizosphere | Mesorhizobium plurifarium | 0.71 | 0.04 | 26.53 |

| Root | Pseudomonas putida | 0.71 | 0.01 | 26.30 |

| Stem | Pseudomonas putida | 0.95 | <0.01 | 75.90 |

| Leaf | Methylobacterium extorquens | 0.80 | 0.02 | 4.70 |

Correlations were calculated with the Dufrene–Legendre indicator species analysis routine (Indval) in R with 10,000 permutations. The P values of the multiple hypothesis tests were corrected with the false discovery rate. NA, no significant association observed.

Metabolic Analyses: Ferulic Acid Degradation Capacity of Isolated Bacterial Strains.

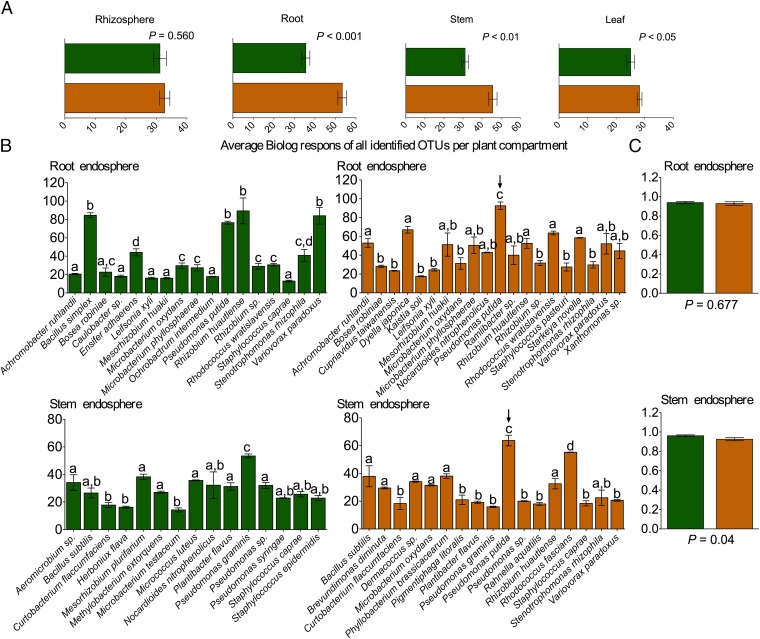

Finally, to quantify the ferulic acid degradation capacity of each isolated bacterial OTU and thereby evaluate the effects of the CCR gene silencing on the individual bacterial metabolisms, we evaluated the bacterial strains of all identified OTUs respirometrically with Biolog MT2 plates (in triplicate) (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the results of the respirometric analysis supported the results at the population level. In the rhizosphere soil, the average ferulic acid degradation capacity of all bacterial OTUs from WT and CCR– poplars was highly similar (P = 0.560). In contrast, bacterial metabolisms within the endophytic communities were significantly dissimilar between both genotypes. The respirometric response was significantly higher in bacterial endophytes isolated from CCR– poplars in the roots (P < 0.001), stems (P < 0.01), and leaves (P < 0.05) than that from the WT, indicating a higher ferulic acid degradation capacity of the bacterial endophytes present in the CCR– trees.

Fig. 3.

Respirometric metabolism analyses by Biolog with 1 mM ferulic acid. (A) Average respirometric responses of all bacterial strains isolated from the different plant compartments per genotype. P values of pairwise comparisons between WT and CCR– poplars within each plant compartment are indicated on the graphs. (B) Species-level OTU breakdown of respirometric responses for the root and stem compartments. Significant differences in variance of parameters at the 95% significance level are indicated with lowercase letters (P < 0.05). Arrows indicate highest responses in the CCR– poplar trees of P. putida. (C) Metabolic evenness of respirometric responses in the roots and stems of WT and CCR– poplar trees.

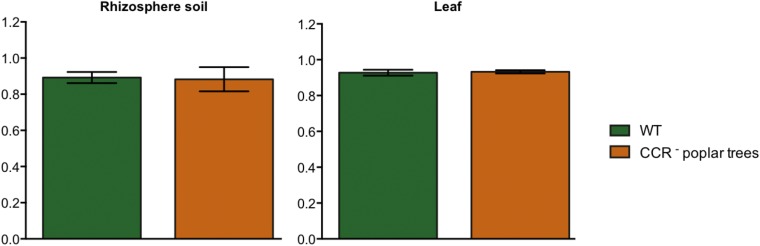

To examine whether the significant differences observed in the average respirometric responses were attributable to a limited number of bacterial strains, we also assessed the metabolism evenness (Shannon) of the bacterial OTUs within each compartment and genotype (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4). For all compartments, the evenness values were highly comparable, except in the stem, where the community metabolic evenness of the CCR– poplar was significantly lower than that of the WT (P < 0.05), indicating that the higher respirometric response in CCR– was limited to specific strains. Further, we evaluated the individual respirometric response of each identified OTU (Fig. 3B and Fig. S5) within each compartment and genotype, to relate the OTU abundance to the respirometric response to ferulic acid. P. putida from roots and stems of the CCR– poplar clearly possessed the highest degradation capacity for ferulic acid. Therefore, the high relative OTU abundance of P. putida in roots (26.3%) and stems (75.9%) (Fig. S1 B and C) of the CCR– trees can be attributed to their efficient ferulic acid degradation (Fig. 3B), whereas in the WT trees no such relation was observed.

Fig. S4.

Metabolic evenness of respirometric responses in the rhizosphere soil and leaf tissues of WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. Evenness was calculated according to Pielou: J′ = H′/ln (S), where H′ is the number derived from the Shannon diversity index and S is the total number of species in the community. Pielou’s evenness is constrained between 0 and 1. Significant differences in variances of parameters were calculated as described in Fig. 1. No significant differences were found at the 95% significance level.

Fig. S5.

Respirometric metabolism analyses with Biolog with 1 mM ferulic acid. Species level OTU breakdown of respirometric responses (individual bacterium responses) for the rhizosphere (A and B) and leaf compartment (C and D). Significant differences in parameter variances at the 95% significance level are indicated with lowercase letters (P < 0.05).

SI Materials and Methods

Field Trial and Sampling Procedure.

The study site was a field trial established in May 2009 (Ghent, Belgium) with 240 poplar trees down-regulated for cinnamoyl-CoA reductase-encoding gene (CCR–), corresponding to 120 copies of two independent transgenic lines each, and 120 WT poplar trees (P. tremula × P. alba) (20). The genetically engineered poplar trees were generated as described (17) and the field trial has been described previously (18). Briefly, both CCR– and WT poplar trees were simultaneously micropropagated in vitro, acclimatized in a greenhouse. Six-month-old greenhouse-grown poplars (2 m high) were pruned and transferred to the field 10 d later. The trees were planted in a randomized block design (six blocks of 20 trees each) at a density of 15,000 trees per hectare and an interplant distance of 0.75 m (18). A border of WT poplar trees surrounded the field to reduce environmental effects on tree growth (17, 18).

Poplar trees (WT and CCR–) were coppiced in February 2010 and allowed to grow further. The trees were sampled in October 2011. Twelve biologically independent replicates (individual trees) were sampled for WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. Samples were spread, as much as possible, between different randomized blocks, taking into account the level of down-regulation as assayed on the samples derived from the first harvest in February 2010. All sampled trees corresponded to redness class 5 (18). Because our main interest was the influence of the genetic modification (CCR down-regulation) of poplar on the plant-associated bacterial communities, we sampled poplar trees with the highest CCR down-regulation. Silencing of the CCR gene is associated with a visible phenotype, namely a red-brown xylem coloration, allowing sampling according to phenotype and, hence, somewhat bypassing unequal levels of gene silencing. Samples included rhizosphere soil, roots, stems, and leaves.

Root samples were collected at a depth of 5–10 cm below ground level. A minimum of 10 g of roots was sampled per individual poplar. Root samples were placed into 50-mL plastic tubes containing 20 mL of sterile 10 mM PBS (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4). Soil particles adhering to the roots were collected as rhizosphere soil, whereas for the stem and leaf samples one complete offshoot of every individual poplar was gathered. To standardize and maximize reproducibility of stem samples, five to seven small stem “cores” with bark (1 cm each) were taken from the base to the top of each offshoot to represent the stem compartment and selected stem cores with highly red wood coloration were selected, indicative for high CCR down-regulation. For the leaf samples, all leaves from the sampled offshoot were collected to represent the leaf compartment.

Processing of Rhizosphere Soil, Root, Stem, and Leaf Samples.

Rhizosphere soil was strictly defined as soil in the immediate vicinity of the roots. Therefore, root samples were washed in 10 mM PBS buffer for 10 min on a shaking platform (120 rpm) and then transferred to clean 50-mL plastic tubes. The soil particles directly dislodged from the roots represented the rhizosphere samples. Plastic tubes were preweighted to correct bacterial cell counts to cfus. Because the focus was on rhizospheric and endophytic bacteria that colonize the internal plant tissues, the epiphytic bacteria were removed from the surface of the plant tissues by sequential washing with (i) sterile Millipore water (30 s), (ii) followed by immersion in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol (2 min), (iii) sodium hypochlorite solution [2.5% (vol/vol) active Cl–, 5 min] supplemented with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80, (iv) 70% (vol/vol) ethanol (30 s), and (v) five times with sterile Millipore water. To confirm the absence of epiphytic bacteria on the surface of the plant tissues and also guarantee the aseptic conditions during the sterilization process, aliquots (100 μL) of the final rinse water were spread on solid rich medium 869 containing 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 5 g NaCl, 1 g d-glucose, and 0.345 g CaCl2·2H2O (pH 7) per liter of deionized water. The plates (negative controls) were examined for bacterial growth after 3 d of incubation at 30 °C. Plant samples were portioned into small fragments with a sterile scalpel and subsequently were macerated in sterile PBS buffer (10 mM) with a Polytron PR1200 mixer (Kinematica A6) in cycles of 2 min (four times) with cooling of the mixer on ice between cycles to reduce sample heating.

Finally, to take into account the biological and microbiological variations, the resulting homogenates (rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf) from three trees were pooled, resulting in four independent biological replicates derived from 12 individual poplars. Additionally, for each biological replicate, a technical replicate was added to all experimental setups.

Bacterial Isolation.

Bacterial cells were isolated from the resulting homogenates of rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf tissues via (i) a direct nonselective and selective isolation technique with a standard carbon source mix and specific phenolic lignin precursors as sole carbon sources, respectively, and (ii) a selective enrichment technique. Furthermore, for all isolation procedures, negative controls (plates and flasks containing only nutrient medium) were included and grown in conditions identical to those of the experimental samples to ensure sterility of the isolation process.

Direct isolation of bacterial cells (selective and nonselective).

In this approach, bacterial cells were isolated by directly plating serially diluted aliquots (100 μL) of the prepared homogenates on inorganic culture solution (38) that contained per liter of deionized water 6.06 g Tris⋅HCl, 4.68 g NaCl, 1.49 g KCl, 1.07 g NH4Cl, 0.43 g Na2SO4, 0.2 g MgCl2·6H2O, 0.03 g CaCl2·2H2O, 40 mg Na2HPO4·2H2O, 10 mL 1.8 mM Fe (III) NH4 citrate solution, and 1 mL of trace element solution SL7 (pH 7) supplemented with either 1 mM p-coumaric acid, 1 mM ferulic acid, or 1 mM sinapic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) as sole carbon source for the selective isolation. To check for normal baseline bacterial cell counts between WT and CCR− poplars, bacterial cells were also nonselectively isolated by means of the same inorganic culture solution, but supplemented with a carbon source mix, namely per liter deionized water 0.52 g d-glucose, 0.66 g gluconate, 0.54 g fructose, 0.81 g succinate, and 0.35 g lactate, optimized to accommodate a large range of bacterial carbon source requirements. Bacterial cultures (selective and nonselective) were incubated (at 30 °C for 7 d), whereafter the cfus per g of rhizosphere soil and per g of fresh plant tissues were determined.

Selective enrichment of bacterial cells.

The best results for the direct selective isolation of rhizospheric and endophytic bacteria were obtained with ferulic acid as sole carbon. Therefore, bacterial cultures were enriched with the same liquid inorganic culture solution as described above supplemented with 2.5 mM ferulic acid. Culture media were inoculated with 2 mL of the prepared homogenates of rhizosphere soil, roots, stems, and leaves. Enriched cultures were incubated for 5 wk (36 d) on a shaking platform (120 rpm) at 30 °C and diluted every 12 d with fresh inorganic culture medium. After 5 wk of incubation, serially diluted aliquots (100 μL) of the cultures were spread on solidified inorganic culture medium (10 g⋅L−1 agar) with 1 mM ferulic acid as sole carbon source. Plates were incubated for 7 d at 30 °C and bacterial cell counts were determined for all samples (rhizosphere soil, roots, stems, and leaves) of WT and CCR− poplar trees. Bacterial strains were grouped based on morphology to create provisional OTUs that were validated with 16S rRNA sequencing. Abundance data (cell counts) for each OTU were also determined. Subsequently, all morphologically different strains were purified in fivefold and subsequently stored at −70 °C in a glycerol solution [15% (wt/vol) glycerol and 0.85% (wt/vol) NaCl] for genomic DNA extraction.

Identification of Bacterial Strains.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing of bacterial amplicons.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from all purified morphologically different bacterial strains in triplicate with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). Bacterial DNA concentrations and purity were evaluated with a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Isogen Life Sciences). Bacterial small-subunit ribosomal RNA genes (16S) were amplified by PCR with ∼50 ng⋅μL−1 bacterial DNA with the 26F/1392R (E. coli numbering) primer pair. The bacteria-specific 26F primer (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′, targeting 16S–23S internally transcribed spacer regions) and the universal 1392R primer (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3′, targeting 16S at 1,392–1,406 bp) span the hypervariable V1-V9 regions (amplicon size: ±1,366 bp). The sequence variability and phylogenetic content of these amplicons allow the highly reliable and reproducible identification of bacterial cultures at a species level. The master mix consisted of 1.8 mM high-fidelity PCR buffer, 1.8 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μM 26F, 0.4 μM 1392R, and 1.25 U high-fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, at 52 °C for 30 s, and at 72 °C for 3 min, and completed with a final elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C (Techne TC 5000 PCR Thermal Cycler). PCR amplicons were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and bidirectionally sequenced by Macrogen under BigDye Terminator cycling conditions (3730XL; Applied Biosystems).

16S rDNA sequence processing and taxonomic assignment.

Partial 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained from Macrogen. Forward and reverse sequences were assembled to construct a 16S rDNA consensus sequence for each bacterial strain with the Geneious package (Biomatters). All consensus sequences were queried against Greengenes (37) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI BLAST). Subsequently, consensus sequences were manually clustered into OTUs based on BLAST homology (97% sequence similarity). Based on previously determined bacterial cell counts and OTU taxonomies, abundance data for OTUs at specific taxonomic ranks (species, genus, family, order, class, and phylum) were calculated for all plant compartments (rhizosphere soil, roots, stems, leaves) and genotypes (WT and CCR− trees). The OTU abundance data were used to construct taxonomic rank-specific matrices for the analysis of the bacterial community structures (discussed below). Finally, the consensus sequences were aligned using the MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MUSCLE) algorithm in Unipro UGENE and taxonomic dendograms were generated with the PHYLIP Neighbor-Joining algorithm (Unipro UGENE) (39). To assess branch supports, bootstrap values were calculated with 2,000 pseudoreplicates.

Univariate Analysis of Bacterial Community Structures and Bacterial Diversity.

Univariate community measures (species richness, species evenness, and species diversity) reduce the large amount of species information into single summary indices. These methods are less robust and sensitive than multivariate analyses (NMDS, canonical analyses) to detect changes in bacterial communities, but represent a valuable addition to the multivariate analysis by providing a higher level of visualization and interpretability. Species richness was calculated with Margalef’s richness index: Dmg = (S − 1)/ln (N), where S represents the number of OTUs in the samples and N the total number of clones in the samples. Species evenness was calculated with Pielou’s evenness index: J = H′/ln (S) where H′ represents the Shannon–Weiner diversity index (H′= −Σ pi ln pi) and S the number of OTUs in the samples. Species diversity was calculated with the inverse Simpson index: D = 1/Σ pi2, where pi is the proportion of clones in the ith OTU.

Respirometric Metabolism Analysis of Pure Cultures with Biolog MT2.

To quantify the ferulic acid degradation capacity of each isolated bacterial strain and evaluate the effect of the CCR down-regulation and the resulting change in xylem composition and available carbon sources on the individual bacterial metabolisms, all isolated bacterial strains were semiquantitatively evaluated with MT2 plates (Biolog). Biolog MT2 plates use redox chemistry to semiquantitatively assess the degradation of external carbon sources. Each well of the Biolog MT2 microplates (96 wells) contains tetrazolium violet redox dye that is highly sensitive to bacterial respiration and a buffered nutrient medium optimized for a wide variety of bacteria. Bacterial respiration (i.e., degradation of the added carbon source) results in the reduction of tetrazolium violet to formazan that can be spectrophotometrically quantified at 595 nm.

For the Biolog MT2 respirometric assay, pure bacterial cultures were grown in liquid rich medium 869 overnight (18 h, 30 °C, 120 rpm). Subsequently, the exponentially growing cultures were washed twice (4,000 rpm, 20 min) with sterile 10 mM PBS buffer and absorbance of all bacterial suspensions was adjusted to 0.200 (600 nm) with sterile 10 mM PBS buffer. Finally, the cultures were incubated at 30 °C on a shaking platform (120 rpm) for 18 h to deplete residual carbon nutrient content. Each well of the Biolog MT2 plates was filled with 5 mM ferulic acid (30 μL) and 115 μL of the designated bacterial suspension at absorbance600 = 0.20, resulting in a final concentration of ∼1 mM ferulic acid per well. Each bacterial strain was tested in triplicate. Positive control wells were filled with 5 mM of d-glucose and three different bacterial strains. Negative control wells were inoculated with 5 mM ferulic acid (30 μL) and 115 μL of sterile deionized water. Inoculated plates were placed in self-sealing plastic bags (VWR) containing a water-soaked paper towel to minimize evaporation from the wells and were incubated at 30 °C. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm with an OMEGA plate reader (Fluorostar) immediately after inoculation (0 h) and at 3, 6, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 144 h. Actively respiring bacterial strains, namely those that degraded the added ferulic acid as sole carbon source, reduced tetrazolium violet to formazan.

Raw absorbance data for all bacterial strains from each time point (3, 6, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 144 h) were collected and individually standardized by subtracting the corresponding absorbance value measured immediately after inoculation (0 h) (reaction-independent absorbance). Furthermore, to semiquantitatively evaluate the degradation capacity of each bacterial strain in the kinetic Biolog dataset, the net area under the absorbance versus time curve was calculated according to the trapezoidal approximation (40)

The resulting value calculated via the trapezoidal approximation summarizes different aspects of the measured respirometric reaction, including differences in lag phases, increase rates, maximum optical densities, and so on (40). Finally the average respirometric responses of all bacterial strains, indicating the ferulic acid degradation capacity, were calculated for the rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf samples of WT and CCR− poplar trees.

Statistical Analysis.

Univariate analysis.

Statistical analyses were done in R 2.15.1 (27). Normal distributions of the data were checked with the Shapiro–Wilkes test and homoscedasticity of variances was analyzed either by the Bartlett’s or the Fligner–Killeens test. Significant differences in the parameter variances were evaluated, depending on the distribution of the estimated parameters, either with ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. Post hoc comparisons were conducted either by the Tukey’s honest significant differences tests or pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Multivariate analysis of bacterial community structures and bacterial diversity.

Statistical analysis of the multivariate ecological data included, according to the recommendations (41) and most recent implementation (42), the following components: (i) robust unconstrained ordination, (ii) rigorous statistical test of the hypothesis, and (iii) indicator species analysis. The OTU abundance data were square-root-transformed (to downweight quantitatively abundant OTUs) and similarities in the bacterial community structures were displayed by means of NMDS with Bray–Curtis distances. NMDS has been identified as particularly robust and useful for ecological data (41). NMDS analyses were done with R (package Vegan) with 10,000 permutations. Comparisons between the different tissues within each genotype (WT and CCR−) were displayed as well as pairwise comparisons between WT and CCR– trees for rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf samples. All of the ordinations were plotted using R (27). Differences between the a priori defined groups (WT and CCR− trees) were evaluated with permutation-based hypothesis tests, namely analysis of similarities (ANOSIM), an analog of univariate ANOVA and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (adonis). Both ANOSIM and adonis were run in R (package Vegan) with 10,000 permutations (27). To evaluate the degree of preference of each species for the a priori defined groups (WT and CCR− trees), a species–genotype association analysis was used. Correlations were calculated with the Dufrene–Legendre indicator species analysis routine (IndVal, indicator value) (43) in R with 10,000 permutations (27).

Conclusion

Host genotype effects that are reminiscent of the host genotype-dependent associations that shape the human microbiome (4, 5) have been identified in plants. The host genotype had a profound effect on the metabolic capacities and bacterial species in the endosphere of CCR-deficient poplar trees, without perceptible effects on the bacterial communities of the rhizosphere. Our data show that the effects of CCR down-regulation go beyond those that could have been expected from perturbation of the lignin biosynthesis as described in textbooks. Indeed, compounds that accumulate because of perturbations in the CCR gene expression are apparently further metabolized by the endophytic community. These new metabolites may interfere with the intended phenotype caused by the perturbation. Clearly, these interactions need to be taken into account when engineering the plant metabolic pathways and to understand their relation to the environment. For this study, we chose a targeted methodology to isolate cultivable bacteria that predominantly focused on the differential accumulation of phenolic carbon sources in the WT and CCR-deficient poplar trees. Implementing high-resolution 16S rDNA sequencing technologies could further elucidate the host genotype-dependent modulation of the plant microbiome by CCR-down-regulation and possibly contribute to the exploitation of the eukaryote–prokaryote associations.

Materials and Methods

A full description of the materials and methods is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Field Trial.

The study site was a field trial established in May 2009 by the VIB with 120 CCR-deficient clonally replicated trees of two independent transgenic lines and 120 WT poplar trees (P. tremula × P. alba). Both CCR– and WT poplar trees were simultaneously micropropagated in vitro, acclimatized in a greenhouse, and 6-mo-old greenhouse-grown poplars (2 m high) were pruned and transferred to the field 10 d later (18, 20).

Collection of Samples.

Samples from four compartments (rhizosphere soil, root, stem, and leaf) were collected from the poplar trees in October 2011 (nWT = 12, nCCR– = 12). Samples were spread, as much as possible, between different randomized blocks, taking into account tree health, general appearance, and CCR down-regulation level visualized by the red wood coloration. All sampled trees corresponded with redness class 5 (18).

Processing of Samples.

Plant tissues were depleted of soil particles and epiphytic bacteria by surface sterilization with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and 0.1% (vol/vol) NaClO. Bacterial cells were isolated from all four compartments via (i) direct nonselective and selective isolation techniques with a standard carbon source mix and specific phenolic compounds (ferulic acid, sinapic acid, and p-coumaric acid) as sole carbon sources and (ii) a selective enrichment technique with ferulic acid.

Identification of Bacterial Strains.

Genomic DNA was extracted from all purified morphologically different bacterial strains in triplicate with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). PCR amplification of bacterial small-subunit ribosomal RNA genes (16S) was done with the 26F/1392R (Escherichia coli numbering) primer pair. All sequences were queried against Greengenes (37) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI BLAST).

Metabolic Analyses.

To quantify the ferulic acid degradation capacity, all isolated bacterial strains were semiquantitatively evaluated with MT2 plates (Biolog).

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analysis of the multivariate ecological species data included (i) robust unconstrained ordination (NMDS), (ii) rigorous statistical testing of the hypothesis (ANOSIM and adonis), and (iii) indicator species analysis (Dufrene–Legendre). Statistical analyses were performed with packages and scripts developed in R (27).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Research Foundation-Flanders Project G032912N, Ghent University Multidisciplinary Research Partnership “Biotechnology for Sustainable Economy” Project 01MRB510W, and Hasselt University Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds Methusalem Project 08M03VGRJ. M.O.D.B. and N.W. were a research fellow and postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1523264113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Turner TR, James EK, Poole PS. The plant microbiome. Genome Biol. 2013;14(6):209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:807–838. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch L. Shaping the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(1):2. doi: 10.1038/nrg3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spor A, Koren O, Ley R. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(4):279–290. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444(7117):323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compant S, Clément C, Sessitsch A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: Their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42(5):669–678. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardoim PR, van Overbeek LS, Elsas JD. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16(10):463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyens N, van der Lelie D, Taghavi S, Newman L, Vangronsveld J. Exploiting plant–microbe partnerships to improve biomass production and remediation. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(10):591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulgarelli D, et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature. 2012;488(7409):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature11336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundberg DS, et al. Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature. 2012;488(7409):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebeis SL, et al. Salicylic acid modulates colonization of the root microbiome by specific bacterial taxa. Science. 2015;349(6250):860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M. Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:519–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanholme R, Demedts B, Morreel K, Ralph J, Boerjan W. Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):895–905. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen F, Dixon RA. Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(7):759–761. doi: 10.1038/nbt1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studer MH, et al. Lignin content in natural Populus variants affects sugar release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(15):6300–6305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009252108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leplé J-C, et al. Downregulation of cinnamoyl-coenzyme A reductase in poplar: Multiple-level phenotyping reveals effects on cell wall polymer metabolism and structure. Plant Cell. 2007;19(11):3669–3691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Acker R, et al. Improved saccharification and ethanol yield from field-grown transgenic poplar deficient in cinnamoyl-CoA reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(2):845–850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321673111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badri DV, Chaparro JM, Zhang R, Shen Q, Vivanco JM. Application of natural blends of phytochemicals derived from the root exudates of Arabidopsis to the soil reveal that phenolic-related compounds predominantly modulate the soil microbiome. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(7):4502–4512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Custers R. First GM trial in Belgium since 2002. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(6):506. doi: 10.1038/nbt0609-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haichar FZ, et al. Plant host habitat and root exudates shape soil bacterial community structure. ISME J. 2008;2(12):1221–1230. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandenkoornhuyse P, et al. Active root-inhabiting microbes identified by rapid incorporation of plant-derived carbon into RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(43):16970–16975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705902104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallmann J, Berg G. 2006. Spectrum and population dynamics of bacterial root endophytes. Microbial Root Endophytes, Soil Biology Series, eds Schulz BJE, Boyle CJC, Sieber TN (Springer, Berlin), Vol 9, pp 15–31.

- 24.McCully ME. Niches for bacterial endophytes in crop plants: A plant biologist’s view. Aust J Plant Physiol. 2001;28(9):983–990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralph J, et al. Identification of the structure and origin of a thioacidolysis marker compound for ferulic acid incorporation into angiosperm lignins (and an indicator for cinnamoyl CoA reductase deficiency) Plant J. 2008;53(2):368–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oksanen J, et al. 2013 Package ‛vegan’: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.15.1. Available at cran.r-project.org.

- 27.R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottel NR, et al. Distinct microbial communities within the endosphere and rhizosphere of Populus deltoides roots across contrasting soil types. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(17):5934–5944. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05255-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinert N, et al. PhyloChip hybridization uncovered an enormous bacterial diversity in the rhizosphere of different potato cultivars: Many common and few cultivar-dependent taxa. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;75(3):497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inceoğlu Ö, Salles JF, van Overbeek L, van Elsas JD. Effects of plant genotype and growth stage on the betaproteobacterial communities associated with different potato cultivars in two fields. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(11):3675–3684. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00040-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danielsen L, et al. Ectomycorrhizal colonization and diversity in relation to tree biomass and nutrition in a plantation of transgenic poplars with modified lignin biosynthesis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett AE, Grussu D, Kam J, Caul S, Halpin C. Plant lignin content altered by soil microbial community. New Phytol. 2015;206(1):166–174. doi: 10.1111/nph.13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, et al. Comparative genomics and functional analysis of niche-specific adaptation in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(2):299–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taghavi S, et al. Genome survey and characterization of endophytic bacteria exhibiting a beneficial effect on growth and development of poplar trees. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(3):748–757. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weyens N, van der Lelie D, Taghavi S, Vangronsveld J. Phytoremediation: Plant-endophyte partnerships take the challenge. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20(2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masai E, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. Genetic and biochemical investigations on bacterial catabolic pathways for lignin-derived aromatic compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71(1):1–15. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(7):5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlegel HG, Cosson J-P, Baker AJM. Nickel-hyperaccumulating plants provide a niche for nickel-resistant bacteria. Bot Acta. 1991;104(1):18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okonechnikov K, Golosova O, Fursov M. UGENE team Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(8):1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guckert JB, et al. Community analysis by Biolog: Curve integration for statistical analysis of activated sludge microbial habitats. J Microbiol Methods. 1996;27(2-3):183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson MJ, Willis TJ. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: A useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology. 2003;84(2):511–525. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartmann M, et al. Significant and persistent impact of timber harvesting on soil microbial communities in Northern coniferous forests. ISME J. 2012;6(12):2199–2218. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.84. and erratum (2012) 6(12):2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Cáceres M, Legendre P. Associations between species and groups of sites: Indices and statistical inference. Ecology. 2009;90(12):3566–3574. doi: 10.1890/08-1823.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life v2: Online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue) Suppl. 2:W475–W478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]