Abstract

Background:

Attention to different aspects of self-efficacy leads to actual evaluation of self-efficacy about physical activity. This study was carried out in order to design and determine psychometric characteristics of a questionnaire for evaluation of self-efficacy about leisure time physical activity (SELPA) among Iranian adolescent boys, with an emphasis on regulatory self-efficacy.

Materials and Methods:

This descriptive–analytic study was conducted in 734 male adolescents aged 15–19 years in Isfahan. After item generation and item selection based on review of literature and other questionnaires, content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were determined and items were modified employing the opinions of expert panel (N = 10). Comprehensibility of the questionnaire was determined by members of target group (N = 35). Exploratory factors analysis (EFA) was operated on sample 1 (N1 = 325) and confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) on sample 2 (N2 = 347). Reliability of SELPA was estimated via internal consistency method.

Results:

According to EFA, barrier self-efficacy and scheduling self-efficacy are the two main aspects of SELPA with the total variance of 65%. The suggested model was confirmed by CFA and all fitness indices of the corrected model were good. Cronbach's alpha was totally estimated as 0.89 and for barrier and scheduling self-efficacy, it was 0.86 and 0.81, respectively.

Conclusions:

The results provide some evidence for acceptable validity and reliability of SELPA in Iranian adolescent boys. However, further investigations, especially for evaluation of predictive power of the questionnaire, are necessary.

Keywords: Adolescents, Iran, physical activity, questionnaire, self-efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Physical activity is a protective factor against chronic non-communicable diseases.[1] Nevertheless, many people do not have adequate physical activity and sedentary lifestyle has become an important public health issue in all age groups, including adolescents.[2,3] Because of increasing consumption of high-calorie food, use of digital technologies, and adopting a sedentary lifestyle in older age, physical activity promotion has become more important in adolescents.[1,3,4,5,6] Nowadays, about 80% of adolescents have neither severe nor mild physical activity more than 60 min per day.[7,8]

Many studies show that self-efficacy (SE) is one of the major determinants of physical activity. This construct plays an important role as the predictor of exercise, and people who have more confidence about their ability show greater participation in physical activity. Likewise, those who engage more in exercise programs also achieve a higher level of general SE.[9,10,11,12,13] According to Bandura, SE expresses one's beliefs in his or her ability to successfully carry out a course of action. He posits that cognitive constructs such as SE have a great impact on physiologically and/or psychologically demanding behaviors like physical activities. The role of SE is strongest during the early stages of participation in physical activities and when this behavior is difficult to do because of some barriers such as fatigue and time constraints.[14]

SE has indirect effects on behavior too, exerting its influence through goals, ideas, outcome expectations, intentions, and perceived barriers and opportunities.[9] Physical activity is a multiple behavior and its performance needs the involvement of a range of motor skills. Therefore, SE about physical activity reflects a range of capabilities required to achieve a final consequence. Some aspects of SE that play a role in initiation of physical activity may differ from other aspects of SE that relate to maintenance of physical activity. According to Bandura, beliefs of SE on special behavior include multiple detention set of management of intellectual, emotional, motivational, and functional processes.[15]

Because attention to these dimensions can be helpful in the achievement of better understanding of the relationship between SE and physical activities, it is necessary to identify the relationship between different aspects of SE and physical activity.[16] McAuley and Mihalko explained “task SE” and “regulatory SE” as the two main types of SE.[17] Task SE is defined as beliefs on ability to perform constituent components of a behavior or a skill. When we consider the type, intensity, duration, and frequency of physical activity, task SE should be studied.[18] So, task SE gives more attention to professional exercise.

Barrier SE is one of the most common and known aspects of regulatory SE that is applied in explanation, prediction, and modification of physical activity. Other aspects of regulatory SE like goal setting efficacy, scheduling efficacy, relapse prevention efficacy, asking efficacy, and environmental change efficacy have already been studied.[16,18] It seems that different aspects of regulatory SE have more importance in promoting participation in physical activity in public health issues.

SE reflects confidence of a person to management and coordination between a set of abilities and skills, not only in countering the barrier but also in commonplace condition. This shows the importance of SE in design and execution of program, besides its ability to overcome the barriers. For this reason, some researchers believe that adoption and maintenance of physical activities require the SE beliefs in goal setting, designing, and implementing. Maddux found that the effect of SE on setting and performing a program is more fundamental than task efficacy.[15,18] Nevertheless, few researchers have considered barrier SE and SE in designing and implementation of physical activities, simultaneously.[15]

Nowadays, most studies are performed by considering “barrier SE.” In addition, researchers who intend to perform cross-sectional or interventional studies on physical activities in Iranian population have attempted to design, translate, or re-translate SE measurement tools. However, there is no evidence of a specially designed questionnaire for measuring barrier SE, program designing SE, and program execution SE among Iranian male adolescents. Because the lack of attention to different aspects of SE can lead to bias in the results of studies and interventions that deal with the relationship between SE and physical activities, this study aims at introducing and evaluating the psychometric properties of the SE questionnaire of leisure time physical activity among Iranian male adolescents, emphasizing the barrier SE, program designing SE, and program execution SE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Type of study and participants

This study was cross-sectional in design and was conducted in Isfahan in the central region of Iran in 2013. Recommended sample size for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is at least 5 to 20 cases per parameter.[19] Comrey and Lee recommended the sample sizes of 200 as fair, 300 as good, and 500 as very good for exploratory factor analysis (EFA).[20] Because CFA and EFA were used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the questionnaire, the main sample was divided into two separate samples for each analysis. Overall, 750 adolescents aged 15–19 years were recruited, of whom 16 participants were excluded while completing the questionnaire. Thus, 734 male adolescents aged 15–19 who fulfilled the inclusion criteria remained and were randomly divided into sample 1 and 2. While entering the data, it was found that the 62 questionnaires had to be excluded due to incomplete filling (Ntotal = 672). The data of Sample 1 (N1 = 325) were used for item analysis and EFA and those of sample 2 (N2 = 347) for CFA.

In order to increase generalizability, randomized multi-stage sampling was used to select the study subjects. Isfahan was divided into three regions with low, intermediate, and high socioeconomic levels, based on previous studies[21] and expert opinions. Then five high schools were selected randomly in each region, as clusters of sampling (totally 15 high schools). After calculating the study sample size (750), the allocated sample size to each high school was estimated based on the total number of students in each school. Finally, the participants were selected according to systematic random sampling method in classes.

Inclusion criteria were parental consent and student assent, lack of health problem that prevented them from performing physical activities, and not being a member of a professional sport teams.

Measurement tools

Data were gathered via a self-administrated questionnaire that consisted of three main parts:

Some of main characteristics of participants, such as age and familial income (demographic characteristics)

Physical activity was measured using the long-version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ). This questionnaire was designed in 1998 by a group of Italian researchers and suggested as the international measurement of physical activity for the age range of 15–69 by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). IPAQ is used to evaluate a subject's estimated metabolic equivalent (MET) on five domains of physical activity consisting of occupational, home and domestic, transportation, and leisure time physical activity (LTPA). IPAQ divides individuals into three groups of total PA: Low activity (less than 600 MET-min/week), moderate activity (between 600 and 3000 MET-min/week), and severe activity (more than 3000 MET-min/week). The amount of LTPA is divided into three levels based on the leisure time that a person spends per week for PA: Less than 60 min, 60–180 min, and over 180 min assumed as low, medium, and high LTPA, respectively.[22] Reliability and validity of Persian version of IPAQ were verified[23,24]

The questionnaire offered for SE consisted of 13 items. Content of the items and the process of selection and generation are described in the following sections. These items measured the degree of confidence of participants in their ability in overcoming barriers, goal setting, and implementation of programs about physical activity using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = absolutely correct, 5 = absolutely incorrect).

Questionnaire generation process

Generation of the items and evaluation of psychometric properties of the questionnaire were done in a current and logical direction that included the following stages: Creating the initial draft of the instrument and selection or generation of items, establishing a jury of experts for completing the qualitative review, and completing the quantitative review based on Lawshe, Venezizno, and Hooper method. In this method, content validity ratio (CVA) and content validity index (CVI) were estimated[25,26] and then, reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated by EFA and CFA.[27]

From the very moment of designing and/or item selection, the validity of the questionnaire was tried to be achieved. So, after review of the literature and some current questionnaires, the main aspects of SE were extracted according to the characteristics of the target group. Then 30 items for the evaluation of SE were designed in Persian on the three following domains: “Overcoming barriers,” “program adjustment,” and “implementation of programs.” Some of these items also had already and similarly been used in previous studies. So, the process of translation and backward translation of these items from English into Persian was performed by two independent health professionals who were fluent in both languages.

To evaluate the “face validity,” a qualitative method was applied.[26] We requested five independent health professionals to give their opinions about the “face validity” and “cultural adaptation” of the initial questionnaire. Thirty items were evaluated based on criteria such as simplicity, intelligibility, relevance, and appropriateness to the target group and also absence of ambiguity. At this stage, eight items were revised and changed in wordage and 10 items were deleted.

Content validity was primarily evaluated by an expert panel that consisted of 10 health educators. They were asked about some of the qualitative characteristics of items, such as compliance to principles of grammar, wording, item allocation, and scaling. According to Lawshe's method, the minimum acceptable cut-off for CVR was 0.62.[25,26] Based on related equation, seven items were not a quorum for CVR and were thus removed. In addition to quantitative evaluation of CVR, propositions for reform were requested from experts for each item that was selected as an unnecessary item. Cultural and linguistic characteristics of Iranian population are the main criteria for item evaluation.

According to Lynn's method, simplicity, clarity, and specificity were considered to calculate CVI. Since 0.79 was selected as the criterion for acceptable CVI,[26] all the 13 items had the efficient criterion for remaining in the questionnaire.

Prior to the pilot study, comprehensibility of the questionnaire was evaluated through the opinions of 35 adolescent boys, none of whom was a member of either sample 1 or sample 2. They stated their opinions about each item via a Likert scale that consisted of the options, “quite understandable,” “understandable,” “fairly understandable,” and “not understandable.” The number of selected options of “quite understandable” and “understandable” was divided by 35 and comprehensibility coefficient of each item was calculated. Acceptable criterion for comprehensibility of each item was equal to or greater than 0.79 and all items met this criterion.

Finally, for estimation of reliability of the questionnaire, “internal consistency” and “test retest” methods were used. In a pilot study, the questionnaires were given to 73 members of the target group who were not from the study population. They completed the questionnaire 2 weeks prior to the study, and then Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the first survey and Pearson correlation coefficient between both surveys were calculated. We considered Cronbach's alpha coefficient and correlation coefficient equal to or greater than 0.70 as satisfactory.[28] Cronbach's alpha of the questionnaire in this preliminary study was 0.82. A total of 62 students participated in the second survey and Pearson correlation coefficient between test and retest showed a strong correlation between SE score in the first and second steps (r = 0.73, n = 62, P < 0.005).

Statistical analysis

“Item analysis” was performed for the evaluation of reliability of the questionnaire and its items on sample 1 (N1 = 325). Reliable and unreliable items were identified by this method.[26,29] So, “inter-item correlation,” “item total correlation,” “variance,” “squared multiple correlation,” and “Cronbach's alpha if item deleted” were evaluated for each item. If the mean score of an item greatly diverged from the total mean score of the questionnaire or its variance was near to zero, that item was deleted.

In addition, we used EFA to evaluate the “construct validity” of the questionnaire on sample 1.[27,29] Since the suggested questionnaire consisted of three types of SE, extraction step was performed by pre-assumption of “principle component analysis.” We also chose “direct oblimin” rotation because of the possibility of correlation between components. Based on pre-assumption of statistical software, the amount of eigenvalue (variance of the factor) was determined to be equal to 1 and the number of items of rotation to establish an appropriate rotational factor was determined to be equal to 25.[29] All these statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 20 software.

Today, use of CFA is common for semantic matching of questions with factors.[27,30,31] Recent procedure is suitable for the evaluation of some characteristics such as unidimensionality of items.[27] So, CFA was performed on sample 2 (N2 = 347), for determination of construct validity, performed to test the fit of data to the model that was suggested by EFA. In this stage, several alternative models were tested. We used AmosGraphic version 20 software (AMOS Graphic) with maximum likelihood estimation procedure assumption and evaluated absolute, comparative, and parsimonious fit indices. The model was considered acceptable if CMIN/DF was between 1 and 5, CFI was greater than 0.8, parsimonious comparative fit index (PCFI) was less than 0.6, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than 0.8, and PCLOSE was greater than 0.005. Fitness of model was confirmed if P value of CMIN was greater than 0.05, CMIN/DF was between 2 and 3, CFI was greater than 0.9, and PCFI was less than 0.5.[19]

Ethical considerations

The study was started after it was approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Isfahan Education Organization. Ethical approval was granted by the Deputy of Research and Technology of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (ID: 39147, Date: December 30, 2012).

The purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants, and researcher emphasized on the confidentiality of the data and voluntary nature of participation.

Parental informed consent and student dissent were considered as the inclusion criteria.

RESULTS

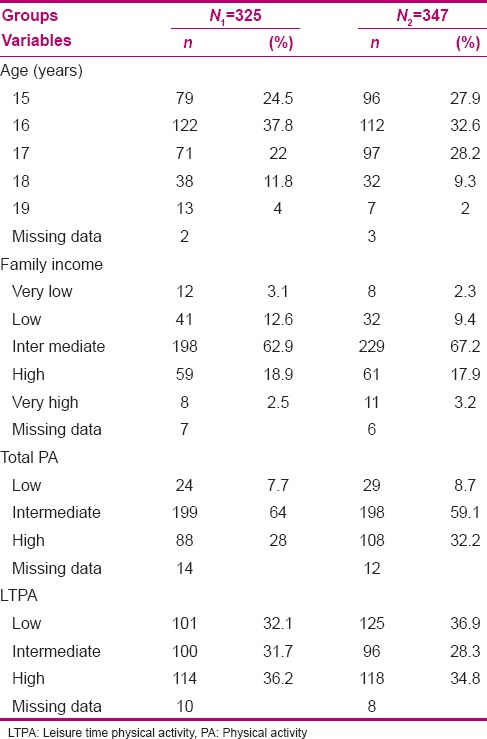

Main characteristics of the participants including samples 1 and 2 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of male adolescents who participated in study

After deletion of outliers and missing data, the average of physical activity and LTPA, based on MET-min/week, was equal to 2421 (SD = 1543) and 902 (SD = 938), respectively.

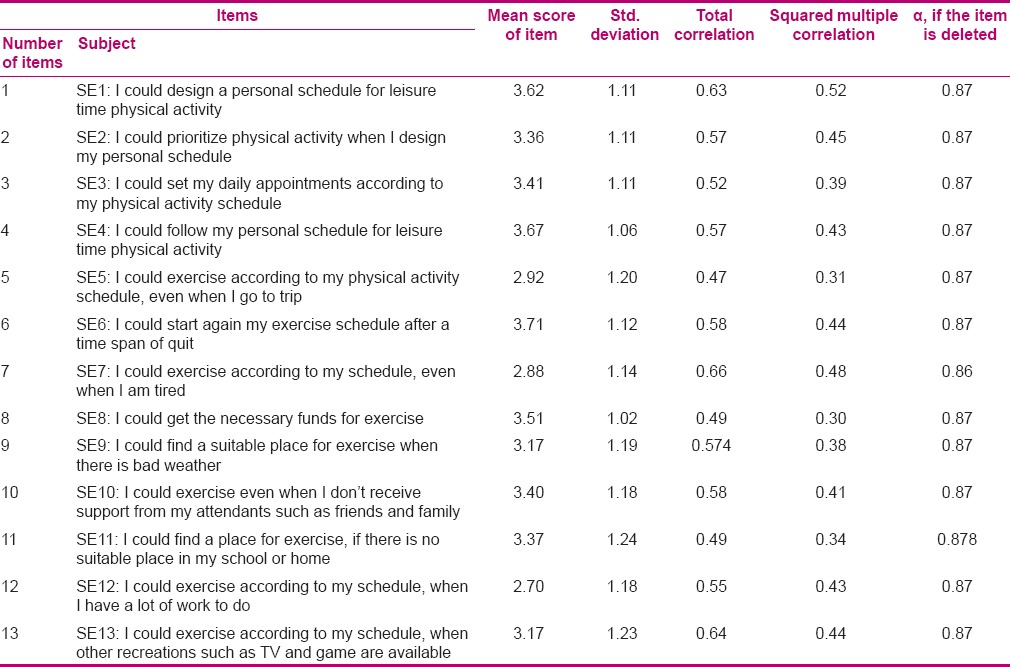

Items analysis

Based on the correlation matrix of sample 1, each of the suggested items had a correlation coefficient higher than 0.4 at least with one of the other items (P ≤ 0.005). According to the results shown in Table 2, all items were suitable and there was no need to remove any item.

Table 2.

Statistics of self-efficacy questionnaire abut leisure time physical activity in Iranian male adolescents

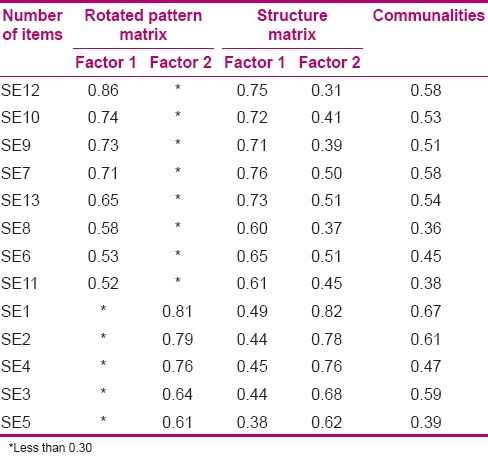

Exploratory factor analysis

The data of sample 1 were analyzed so as to extract the principal components with direct oblimin rotation. Results revealed that Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index was equal to 0.89 and the results of Bartlett's test of sphericity were significant at the confidence interval of 95% (χ2 = 1544, df = 78, P ≤ 0.00). According to the adequacy of sample volume and proportion of correlation matrix with factor analysis, the data were entered into the EFA process.

Regarding the theoretical framework of the study and as the questionnaire consisted of three aspects of SE, we expected that three-component models would be approved. However, principle component analysis showed two components with “eigenvalue” up to 1. “Component matrix” was supported strongly by two-component models also. This result was supported by “scree plot diagram.” Observing a point of failure after three components convinced us to examine other probable solutions. In addition, results of parallel analysis that were analyzed by Monte Carlo physical activity software also supported the two-component solution. Based on these results performed with 13 variables, 325 participants, and 100 repeats and match assumption, only two components had eigenvalue higher than the criterion values that were appropriate with randomized data. These two components explain 51.6% of variance of SE and the results of “rotated pattern matrix” are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Rotated component and pattern matrix with PCA and direct oblimin rotation for items of self-efficacy questionnaire related to leisure time physical activity in Iranian male adolescents

Confirmatory factor analysis

In order to verify the construct validity of the questionnaire, fitness of several models, including 13 items, was specified and evaluated with the sample 2 using CFA. The second-order model demonstrated more acceptable indices compared to first-order model. However, only some fit indices supported the acceptable fitness of second-order model with data of sample 2, so the model needed to be modified (CMIN = 212.50, CMIN/df = 3.32, CFI = 0.92, PCFI = 0.76, RMSEA = 0.082, PCLOSE = 0.000).

Since all unstandardized estimated parameters were significantly different from zero at the 0.001 level (two-tailed), no items were removable. So, to improve the model fit, modification indices were noted. It was found that addition of two parameters between error variables of items 2 and 4 and items 6 and 12 led to a decrease in Chi-square. Adding these covariance parameters had methodological acceptance. Moreover, theoretical framework of the study supported the correlation between error variables of these items. So, “corrected model” was designed via two rating reduction of degree of freedom. Fitness indices approved the appropriateness of the corrected model totally (CMIN = 165.53, CMIN/df = 2.67, CFI = 0.95, PCFI = 0.75, RMSEA = 0.069, PCLOSE = 0.007).

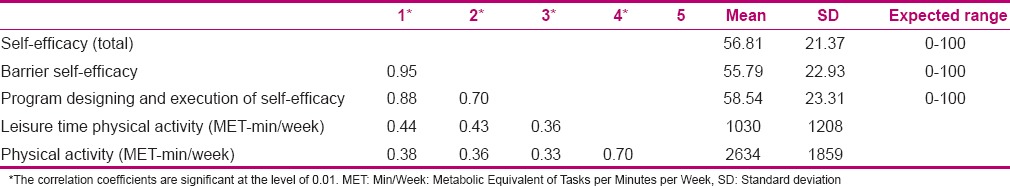

Descriptive and bivariate correlation test

Results of descriptive and bivariate correlation test such as main score of SE and its subconstructs are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The mean, standard deviation, and reciprocal correlation between different aspects of self-efficacy and leisure time physical activity in adolescent boys

DISCUSSION

This article reports the development process and evaluation of psychometric properties of a questionnaire for the determination of SE about leisure time physical activity (SELPA). SELPA was developed to evaluate the main aspects of SE among Iranian male adolescents via 13 items. This process had seven stages. After item generation or translation (first stage), comprehensibility of the items was evaluated (second stage). The psychometric properties of SELPA were evaluated in a current and logical direction, including face validity (third stage), content validity (fourth stage), item analysis (fifth stage), and construct validity by EFA (sixth stage) and CFA (seventh stage).

Previous research and related questionnaires were reviewed as the first step of item generation.[30,31,32] Brons and Gorow believe that review of literature, obtaining comments from experts, and targeted population are the most important steps to achieve content validity of the measurement tools.[33] In the current study, after the literature review, recommendation of 10 health experts from the research group helped us to achieve content validity. Cultural and linguistic characteristics of the target group were considered in modifying the remaining items in different aspects of SE related to LTPA in all stages. Both CVI and CVR supported the content validity. In addition to expert panel, during the primary study, the members of the target group represented their recommendation about comprehensibility of the questionnaire.

Reliability was evaluated in three steps by internal consistency and test–retest method. In each stage, the results supported the reliability of the questionnaire.

One of the main strengths of this study is that two different populations were employed for the evaluation and confirmation of construct validity of the questionnaire by EFA and CFA. The significant outcome of EFA is that SELPA has acceptable construct validity.

EFA showed that two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 loaded on all 13 items significantly and explained 51.6% of the variance of SE. The first factor loaded on items 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13, as we expected. These items addressed the current impediments and challenges of LTPA in Iranian male adolescents that were derived from literature review and expert panel. This factor is called “barrier SE” and its related items consist of obstacles such as fatigue, lack of money, lack of support, time conflict, bad weather, lack of facilities, and present other Competitor Entertainment. The highest correlation was related to item 12 (0.86). This item was considered the participant's ability in continuing physical activity even in the compacted curriculum. The lowest correlation rate was allocated to item number 11 (0.52) that is associated with lack of suitable place for physical activity. Results of this study about the beliefs of adolescents about overcoming barriers may be different from those of other investigations. Noroozi et al. reported that the strongest and weakest factor loading belonged to feeling depressed and feeling physical discomfort after exercise, respectively.[34] That investigation was conducted on Iranian diabetic women and the difference in characteristics of the target groups justifies such results.[15] The second factor loaded on items 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. This result disagrees with our notion. We assumed that these items would be divided within two factors as SE about “program adjustment” and “implementation of programs.” The highest correlation was related to item 1 (0.81). This can be attributed to the confidence of a person to his or her ability to design a program for physical activity. Also, the lowest correlation rate was allocated to item 3 (0.61). This item is associated with competition of occupational or friendly appointment with physical activity. All the items on which factor 2 loaded were related to scheduling SE. Compared to other questionnaires that commonly focus on barrier SE, SELPA considers an important aspect of regulatory SE, named “scheduling SE” about physical activity in leisure time. Rodgers et al. noted that considering scheduling SE is essential for improving the effectiveness of interventions in physical activity.[15]

Since using CFA is recommended to confirm the fitness of conceptual model suggested by EFA, the research group operated this statistical analysis on a separate population.[27] The CFA supported the construct validity of SELPA too. Correction of the model was conducted based on modification indices by adding two covariance to the model, all fit indices shift into good fitness as Noroozi's study.[34]

Results of descriptive and bivariate correlation test, such as main score of SE and its subconstructs, can be considered as the evidence that target group members also perceive moderate confidence to overcome the barriers and design or operate program for physical activity [Table 4]. Robbins et al. showed a similar result in American adolescents in 2004 and reported the perceived SE score of adolescents as 34.2–62.5.[35] Similar results were obtained in Iranian adolescents too.[36,37] Correlation matrix showed that both subconstructs of SE have a moderate correlation with LTPA. This result is consistent with previous researches, especially those that have posited the importance of social cognitive constructs on physical activity. For example, Sriramatr et al. explained a moderate correlation between coping (barrier) (r = 0.33) and scheduling SE (r = 0.35) with energy consumption via physical activity in 364 young students in Thailand.[38] Kim et al. showed a moderate correlation between SE and exercise in adolescents too (r = 0.45).[39] However, some investigations have found a stronger correlation. Taymoori et al. have reported the highest correlation coefficient (r = 0.62) between barrier SE and physical activity in Iranian female adolescents.[37,38] This difference can be justified by population characteristics, idiographic nature of barriers, or instruments’ specifications. Finally, the correlation pattern supports the importance of barrier compared with scheduling SE, similar to other investigations.[15]

CONCLUSION

Since the availability of a specific questionnaire based on specific characteristics of the target groups is important and as all important subconstructs of SE should be taken into consideration, SELPA was developed for the assessment of important aspects of “self-regulatory efficacy,” such as barrier and schedule SE, in Iranian male adolescents. Findings support that barrier and scheduling SE about physical activity can be conceptually and statistically distinguished from each other. This study supported the comprehensibility, face validity, content and construct validity, reliability, and internal consistency of SELPA. However, further investigations are necessary to evaluate the reliability, concurrent validity, comprehensibility, and applicability of the questionnaire through supplementary descriptive and interventional studies. So, improvements of SELPA are warranted. Also, regression analysis is recommended to explore the predictive power of this questionnaire on physical activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank those who helped us in conducting this investigation, including all involved students, teachers, and school managers. In addition, the expert panel is appreciated for revising and estimating the questionnaire's validity and the Research and Technology Deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This article has been derived from the thesis for PhD degree on health education and promotion in Isfahan School of Public Health, which was supported by the Deputy of Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and its number is 391476

Conflict of Interest: I guarantee that there is not any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelishadi R, Ghatrehsamani S, Hosseini M, Mirmoghtadaee P, Mansouri S, Poursafa P. Barriers to physical activity in a population-based sample of children and adolescents in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1:131–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen J, Bertollini R, Victora C, Saracci R. Global response to non-communicable diseases-the role of epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1219–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojtyła-Buciora P, Stawińska-Witoszyńska B, Wojtyła K, Klimberg A, Wojtyła C, Wojtyła A, et al. Assessing physical activity and sedentary lifestyle behaviours for children and adolescents living in a district of Poland. What are the key determinants for improving health? Ann Agric Environ Med. 2014;21:606–12. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1120611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopinath B, Hardy LL, Baur LA, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e167–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirasteh A, Hidarnia A, Asghari A, Faghihzadeh S, Ghofranipour F. Development and validation of psychosocial determinants measures of physical activity among Iranian adolescent girls. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolatabadi NK, Eslami AA, Mostafavi F, Hassanzade A, Moradi A. The relationship between computer games and quality of life in adolescents. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:20. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.112691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380:247–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micklesfield LK, Pedro TM, Kahn K, Kinsman J, Pettifor JM, Tollman S, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior among adolescents in rural South Africa: Levels, patterns and correlates. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9:75–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashford S, Edmunds J, French DP. What is the best way to change self-efficacy to promote lifestyle and recreational physical activity? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15:265–88. doi: 10.1348/135910709X461752. HYPERLINK “http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=What+is+the+best+way+to+change+self-efficacy+to+promote+lifestyle+and+recreational+physical+activity%3F+A+systematic+review+with+meta-analysis” \o “British journal of health psychology.” . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity, self-efficacy and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys. 2012;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanath K. Models of interpersonal health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint; 2008. pp. 170–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner LM, Schuz B, Wolff JK, Parschau L, Wurm S, Schwarzer R. Sources of self-efficacy for physical activity. Health Psychol. 2014;33:1298–308. doi: 10.1037/hea0000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAuley E, Mailey EL, Mullen SP, Szabo AN, Wójcicki TR, White SM, et al. Growth trajectories of exercise self-efficacy in older adults: Influence of measures and initial status. Health Psychol. 2011;30:75–83. doi: 10.1037/a0021567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodgers WM, Wilson PM, Hall CR, Fraser SN, Murray TC. Evidence for a multidimensional self-efficacy for exercise scale. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2008;79:222–34. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2008.10599485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan GJ, Dzewaltowski DA. Comparing the relationships between different types of self-efficacy and physical activity in youth. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:491–504. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuley E, Mullen SP, Szabo AN, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey EL, et al. Self-regulatory processes and exercise adherence in older adults: Executive function and self-efficacy effects. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan EL, Prapavessis H, Campbell N, Gray C, Elkayam J. The effect of a multifaceted efficacy intervention on exercise behavior in relatives of colon cancer patients. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19:550–62. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghasemi V. Tehran: Jameeshenasan; 2011. Structural Equation Modeling in Social Researches Using Amos Graphics; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson RH, Mundform DJ. Recommended sample size for conducting exploratory factor analysis on dichotomous data. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2010;9:359–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nastaran M, Abolhasani F, Izadi M. Application of taps technique for analysis and Prioritize Sustainable urban development. Journal of Geography and Environmental Planning. 1389;38:83–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandelanotte C, Sugiyama T, Gardiner P, Owen N. Associations of leisure-time internet and computer use with overweight and obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviors: Cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moini B, Jalilian F, Jalilian M, Barati M. Predicting factors associated with regular physical activity among college students applying BASNEF model. J Hamedan Univ Med Sci. 2010;18:70–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baghiani Moghaddam MH, Bakhtari Aghdam F, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Allahverdipour H, Dabagh Nikookheslat S, Safarpour S. The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: Content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl Sci J. 2012;18:8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cottrell RR, McKenzie JF. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers Inc; 2005. Health Promotion and Education Research Methods; Using the Five Chapter Thesis/Dissertation Model; pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajizadeh E, Asghari M. 1st ed. Tehran: Sazemane Fntesharate Jahade Daneshgahi; 2010. Statistical Methods and Analyses in Health and Biosciences; pp. 399–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izanloo B, Habibi M, Bagherian-Sararoudi R. The necessity of unidimensionality of indicators in the behavioral and medicine sciencesmeasurements: Application of structural equation modeling. J Res Behave Sci. 2014;11:671–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IR. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. Psychometric Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brace N, Kemp R, Snelgar R. 3rd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2006. SPSS for Psychologists: Aguide to Data Analysis Using; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:421–37. doi: 10.1348/135910705X53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson TM, Rosenfeld BD, Sit L, Mendoza TR, Fruscione M, Lavene D, et al. Using Confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate construct validity of the brief pain inventory (BPI) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:558–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allison KR, Dwyer JJ, Makin S. Perceived barriers to physical activity among high school students. Prev Med. 1999;28:608–15. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaghmai F. Content validity and its estimation. J Med Educ. 2003;3:25–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noroozi A, Ghofranipour F, Heydarnia AR, Nabipour I, Tahmasebi R, TavafianM SS. The Iranian version of the exercise self-efficacy scale (ESES): Factor structure internal consistency and construct validity. Health Educ J. 2010;70:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robbins LB, Pender NJ, Ronis DL, Kazanis AS, Pis MB. Physical activity, self-efficacy, and perceived exertion among adolescents. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:435–46. doi: 10.1002/nur.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taymoori P, Rhodes RE, Berry TR. Application of a social cognitive model in explaining physical activity in Iranian female adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:257–67. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aghamolaei T, Tavafian SS, Hasani L. Cognitive factors related to regular physical activity in college students. Nurs Pract Today. 2014;1:40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sriramatr S, Berry TR, Rodgers WM. Validity and reliability of thai versions of questionnaires measuring leisure-time physical activity, exercise-related self-efficacy, outcome expectations and self-regulation. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2013;17:203–16. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YH, Cardinal BJ. Psychsocial correlates of Korean adolescents physical activity behavior. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2010;8:97–104. [Google Scholar]