Abstract

Introduction:

In the recent years, there has been renewed interest in strengthening primary care for improved health services delivery. Family medicine with its holistic principles is an effective approach for building primary care workforce in resource constraint settings. Even though this discipline is well established and mainstreamed in Western countries, the same is yet to occur in low- and middle-income nations. India with its paradigm shift for universal health coverage is strategically poised to embrace family medicine as a core component of its health system. However, till date, a clear picture of family medicine teaching across the country is yet to be available.

Methods:

This paper makes an attempt to assess the landscape of family medicine teaching in India with an aim to contribute to a framework for bolstering its teaching and practice in coming years. The objective was to obtain relevant information through a detailed scan of the health professional curricula as well as mapping independent academic programs. Specific areas of interest included course content, structure, eligibility criteria, and accreditation.

Results:

Our findings indicate that teaching of family medicine is still in infancy in India and yet to be mainstreamed in health professional education. There are variations in family medicine teaching across academic programs.

Conclusion:

It is suggested that both medical and nursing colleges should develop dedicated Departments of Family Medicine for both undergraduate and postgraduate teaching. Further, more number of standalone diploma courses adopting blended learning methods should be made available for in-service practitioners.

Keywords: Family medicine, India, postgraduate, primary care, teaching, undergraduate

Introduction

India, a country of 1.2 billion people, is still struggling in attaining the country-specific millennium development goals.[1,2] India's quality of primary care has been reported to be suboptimal overall with a score of 52%, having substantial repercussions on health outcomes and health system performance. Considering the national government's vision to implement health assurance in coming days, it is imperative to rebuild primary health services, in both rural and urban India.[3,4,5,6] Primary health care ought to be a good gatekeeper and should be able to prevent a large number of conditions from deteriorating to the extent that they require secondary and tertiary care. It should also receive and provide continued care for people as they return from secondary and tertiary care so as to reduce the escalating healthcare costs.[7] Worldwide, family medicine has been acknowledged as a necessary ingredient for a responsive and robust primary care. Family medicine, also known as a general practice in some countries is a specialty of medicine concerned with providing comprehensive care to individuals, families, and communities, and integrating biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences.[8] Although a new entrant to the developing world, it is an integral and established discipline in developed countries such as USA, The Netherlands, and UK since 1950s.[9] Following the World Health Organization's (WHO's) emphasis on “primary care, more than ever” which suggested low- and middle-income countries to embrace family medicine, various initiatives have been rolled out in many East European countries and Sub-Saharan Africa.[10,11] Accordingly, family medicine has been identified as a thrust area in India in the latest national health policy, with measures to impart its teaching.[12] However, to date, little information is available on family medicine education in South Asian region with few recent publications describing the situations in Sri Lanka and Nepal.[13]

In India apart from the national health policy 2002, several other policy documents such as Mehta Committee Report 1983, National Knowledge Commission Report 2007, Planning commission health committee report 2012, MCI Vision 2015, National Consultation on Family Medicine 2013 etc have stressed upon the importance of family medicine specialty in India. However, we are yet to have a fuller picture of the current status, including, course content, structure, selection, teaching methods, and how students are evaluated in family medicine. The objective of the present study is to map courses relating to family medicine and analyze the course content, duration, and mode of delivery. It is expected that the results would provide critical inputs for strengthening family medicine teaching at multiple levels.

Methods

In order to obtain the best available insights into the imparting of family medicine teaching in India, we adopted an iterative process.[14] A detailed internet search was carried out to identify family medicine courses. The websites of Association of Indian Universities, Indian Council of Medical Research, Universities Grants Commission, Medical Council of India (MCI), Indian Nursing Council, and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare were also searched. A similar search in the websites of the Indira Gandhi National Open University, professional associations namely Indian Medical Association, Academy of Family Physicians of India (AFPI), World Association of Family Doctors (WONCA), WHO, and various public health institute, corporate hospitals, and autonomous medical institutes such as All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, PostGraduate Institute, Chandigarh, Jawaharlal Institute of PostGraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, etc., was also carried out in March 2015. The search was limited to courses offered in India and to collaborations between Indian and foreign institutes, if any. Detailed information about the courses was collected from the institutions’ designated websites as well as through telephonic contacts. Short-term courses spanning few days - few weeks, seminars, and workshops were excluded. To examine the extent of family medicine teaching within the ambit of health professional education, a thorough scan of respective curricula was performed. Syllabi of community medicine in undergraduate medical, dental, nursing, and allied health sciences were analyzed to map family medicine specific content. Further, masters/diploma in public health and/management programs were examined to identify family medicine teaching, if any.

Courses were analyzed for: (1) Whether family medicine is a part of the teaching curriculum, (2) the mode of teaching, (3) the broad contents, (4) the instructional formats or methods being used to teach, (5) if there is any assessment, and (6) the students’ selection process. The specification on where, how, and what is taught in family medicine was summarized and compiled into a matrix. Salient characteristics namely duration, institution, mode of teaching, and eligibility criteria were noted.

Results

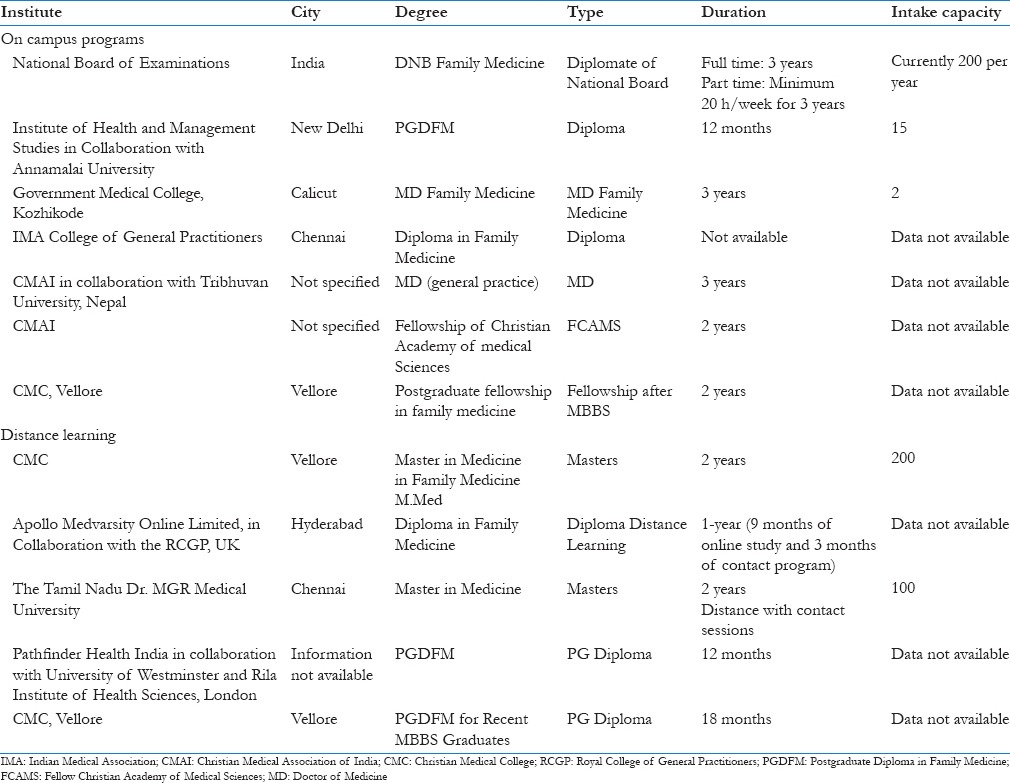

Currently, family medicine teaching is imparted in two ways, full-time degree programs (Diplomate of National Board [DNB] and Doctor of Medicine [MD]) or distance learning courses [Table 1].

Table 1.

Courses on family medicine in India

Family medicine has been recognized in India as a distinct academic specialty for a long time. Family medicine is also included in the list of recognized list of post graduate qualifications of National Board of Examination (Notification of 1983) and Medical council of India (PG Regulation 2000). DNB Family Medicine is a postgraduate degree level, 3 years residency course conducted by the National Board of Examinations at the accredited teaching hospitals. On successful completion of this 3-year residency, candidates are awarded DNB (Family Medicine). The curriculum of DNB (FM) comprises: (1) Medicine and allied sciences, (2) surgery and allied sciences, (3) maternal and child health, and (4) basic sciences and community health. During their 3-year residency, candidates receive integrated inpatient and outpatient learning. They also receive field training at community health centers and clinics. Earlier, only DNB family medicine training was available at National Board of Examination affiliated institutions. Recently, the number of NBE accredited institutions providing family medicine residency training has increased. At present, there are about 200 DNB postgraduate training posts available annually at 60 NBE accredited health institutions in India. The MD (Family Medicine) is a 3 years residency program approved by the MCI. On successful completion, candidates are awarded MD (Family Medicine). Government Medical College, Calicut, Kerala, has become the first institute to start the MD family medicine program in India in 2011. Institute of Health and Management Studies in partnership with the Annamalai University is administering a 12-months program leading to the PostGraduate Diploma in Family Medicine (PGDFM). The aim of the PGDFM program is to construct the ability of general practitioners and enable them to manage more cases so that referral becomes fewer. The curriculum is primarily problem-based. Master in medicine in family medicine (previously known as PGDFM) is a distance education course of 2 years with 30 days of contact program and offered at CMC, Vellore. It aims at capacity building of general practitioners, managing multiple problems, managing risk, effective medical care, screening and prevention, continuity of care, comprehensive care, information management, and quality assurance. The Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medical University, Chennai, also administers a similar program of 2 years master of medicine in family medicine which involves distance learning with contact sessions and practical attachments. Rila Institute of Health Sciences with Pathfinder Health India, a primary healthcare organization, administers a PGDFM validated by Westminster University, London, and endorsed by the National Association for Primary Care, London. Medanta Medicity, one of India's multispecialty institutes, has partnered with the Rila Institute of Health Sciences for the India Hub. The course runs over approximately 9 to 12 months with a mix of online learning and face to face workshops/lectures. Assessment is partly by continuous assessment of the reading topics and mini-tests, both carried out online with a final examination. This “Diploma in Family Medicine” course by Medvarsity is being jointly delivered by Apollo Hospitals Group and the Royal College of General Practitioners, UK. Eligible candidates should have MBBS with MCI registration. The course includes 9 months of online study and 3 months of contact program at any one of the accredited Apollo Hospitals across India during which the candidate will be posted in various departments on a rotational basis. The students are awarded the “Diploma in Family Medicine” jointly by Medvarsity and RCGP. The Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka, in conjunction with the Indian Medical Association's College of General Practitioners offers a 1-year “Diploma in Family Medicine” course through distance mode. The students should be doctors with minimum 5 years of experience in general practice. Since the MCI requires 3-year residency for family medicine specialty, these diplomas are not recognized qualifications in India. Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute, now Sri Ramchandra University offers a Diploma in Family Health administered by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, it has a blended approach with distance teaching complemented by contact sessions. The CMAI in collaboration with Tribhuvan University, Nepal, is offering two postgraduate degree level residency courses namely MD General Practice (3 years) and Fellow Christian Academy of Medical Sciences (2 years) with 97 physicians being trained since 1989. It is yet to be recognized by the MCI. A few of the newly set up AIIMS institutes have designated Departments of Community and Family Medicine and are contemplating to start MD in Community and Family Medicine in near future. The Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj Medical University is planning to start a new course of MD in Family Medicine under a central initiative.[15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]

At present, there are 398 medical colleges in India which enroll approximately 52,255 students every year. At present, 218 colleges offer MD in community medicine whereas 39 institutes offer DPH and six have DCM programs. Family medicine is not included per se in DPH/DCM curricula. The undergraduate curriculum in India does not have a specific family medicine component while the nursing counterpart is incrementally better with few components on family nursing. Postgraduate Programs (MD) in Community Medicine and Nursing have an explicit focus on primary care but not so much on the family medicine. There is no offering of core or elective courses on family medicine in these educational programs. Few exceptions exist such as CMC, Vellore, where teaching of family medicine in the undergraduate and postgraduate courses are routinely being undertaken. However, such pedagogical innovations are limited to selected institutions. Currently, a total of 31 institutions offer master's in public health program in India. No program has family medicine as specialization.[27]

Lack of family medicine has resulted into skewed UG and PG seats in India as compared to countries such as USA and UK where family medicine facilitates engagement of medical graduates into community based system and provided full career path within the primary care care vocation. In USA and UK almost all medical graduates have opportunity to earn post graduate qualification. Family medicine is a community based horizontal specialty which facilitates and ensures availably of medical doctors for community bases health services on a long term basis.

Discussion

Primary health care has been identified as the most cost-effective way to deliver high-quality primary care services since the Alma Ata declaration. Various global health experts, including the World Association of Family Doctors (WONCA), have underscored the paramount importance of family medicine in revitalizing primary care services.[28] In India, the same was reiterated by the Bhore Committee.[29] The unique features of primary care encompass first contact, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination. While an array of health professionals is essential for the delivery of health services, family physicians or general practitioners are particularly well suited to this functions because they are trained to care for individuals of all ages. They also serve as integral, complementary members of primary health care team, providing supervision for other health workers and ensuring comprehensiveness, continuous, and coordinated health care for individuals, families, and communities.[13] The recently formulated draft for national health policy has emphasized the importance of promoting family medicine training in the country to strengthen primary care workforce, and thus reduce the unmet needs of specialist services.[12] Our landscaping of family medicine courses has revealed three major findings which are critical: Lack of mainstreaming of family medicine teaching in undergraduate medical and nursing education, nonexistence of family medicine specialty, and limited scope for capacity building with paucity of accredited courses.

In view of the envisioning of universal health coverage, the first and foremost task is to build our primary care delivery system to deliver major bulk of the integrated care. The current triple burden of diseases poses a formidable challenge for the health system to manage the preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative health care needs of the population. Thus, creating a cadre of family physicians at the forefront could cater to these health needs efficiently. However, the nonexistence of Postgraduate Departments or Teaching Departments of Family Medicine is a major impediment. Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, and even neighboring countries such as Nepal and Pakistan have residency programs conducted by University Departments of Family Medicine in collaboration with the Department of Health. In Bangladesh, postgraduate courses in family medicine are conducted by the University of Science and Technology, Chittagong, the Bangladesh College of General Practitioners, and the Bangladesh Academy of Family Physicians. Sri Lanka has family medicine formal courses, which are chosen by physicians as a career specialty.[9]

Traditionally, family medicine has remained as an unattractive profession for medical students and practicing owing to its perceived low importance and assigning low prestige compared to other medical fields. Unless Departments of Academic Family Medicine exclusively are set up in medical colleges, medical students will have no exposure to the concept resulting into lower preference for family medicine career. All the major family medicine organizations such as AFPI, medical and nursing councils, medical colleges, and policy makers can collaboratively evolve a system to promote the recognition of family medicine as a specialty.

Further, the outputs in terms of annual number of trainees are very small against the huge number of CHCs and PHCs in the country. Up to 60% of the specialist posts are vacant in National Health Mission where family medicine doctors are most suitable to work.[16] Given the few available training opportunities in family medicine, the career trajectory for primary care physicians in public service appears to be restricted. This might act as a deterrent for many general practitioners who despite willing to improve knowledge and skills remain untrained and start practicing in the community or health facility after completion of their undergraduate training without any further education. Mostly, the primary care physicians are being trained on national health programs or specialized certificates in obstetrics or anesthesia, which cannot be equated with family medicine, a discipline much more comprehensive and holistic in nature.[29,30] It may be noted that MCI has already highlighted this deficiency and incorporated measures to include family medicine teaching in the undergraduate curricula.

Training for general practice has been mandatory in UK since 1981. In 1986, the European Community introduced legislation to make specific training for general practice mandatory in all member states and should be fully implemented by 1995. Nowadays, vocational training is an obligation in many of the European countries. Similar initiatives could be thought of in India with opportunity for the practicing physicians who are medical graduates or specialists other than family medicine to practice in primary care. In service learning, using a blend of distance education with contact sessions could be considered, given the problem of sparing physicians for a longer duration. However, the assessment process has to be rigorous in such trainings. One option could be to build skills amongst practicing doctors through refresher training. In Turkey, a phased retraining program and transition period training (TPT) was undertaken as a temporary model. TPT covered all the physicians who wanted to work as a family physician. The training was performed only for the transition period and was tapered once the needed number of trained physicians was reached.[9]

The importance of incorporating and mainstreaming family medicine in medical and nursing education is clearly established. Most of the undergraduate programs in family medicine in Western countries are now conducted in clinical years.[9] In Sri Lanka and South Africa, similar initiatives have shown encouraging results.[11,13] Contrastingly, in India, there is a void of family medicine in current undergraduate medical education. It is well evident that future health care professionals will need strong skills in the fundamental aspects of family medicine to gain confidence and expertise in dealing with complex physical, psychological, and social problems, as first contact physicians. This calls for curricular enhancements for successful integration of family medicine into medical and allied health professional education. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of longitudinal integration of curricular enhancements in medical school education to avoid competition for concentrated time in the curriculum and to enable ongoing reinforcement of the interconnectedness of individual health and the health of the community. Given the current restricted MBBS curriculum, leaving little room for additional elements, a revisiting of the curriculum should identify an achievable and effective strategy for integrating critical skills of family medicine. More so, this should be complemented with faculty development initiative inbuilt to the program.[29,30]

At present, there is no agreed-on set of public health competencies that family physicians should possess to effectively face diverse public health medicine.[8] Therefore, weaving public health and preventive medicines into family medicine will enrich the curriculum. These constructs are even more important since primary care physicians in India are often challenged with various public health problems. The future Family Medicine Departments should work in synergy with Departments of Community Medicine and combine expertise and knowledge. This, in turn, would produce appropriately trained and adequately competent higher quality primary care workforce. Family medicine departments could also pool and share infrastructure/faculty from generalist specialties such as general medicine, general pediatrics, OBG and general surgery. Community based health facilities such as district hospitals, sub divisional hospitals and community health centres (CHC) could be developed into teaching locations and generalist specialists working at these facilities could be groomed as faculty of family medicine.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The family practice profession being uniquely committed to a biopsychosocial approach resonates remarkably well with the tenets of primary health care. However, in India, family medicine has not been developed as a full-fledged discipline and continues to be a missing ingredient in medical and nursing education as well as professional development trainings. A multidimensional strategy is needed to mainstream family medicine into current health professional education. The hallmarks of such multidimensional strategy should include: (1) Vertical and horizontal integration throughout the curriculum; (2) a unifying institutional framework; (3) emphasis on experiential learning; and (4) faculty development. Such trainings would increase the number of well-trained physicians who have the knowledge, skills, and commitment needed to meet the health needs of the community and patients attending primary and community health centers.

A strong policy directive with detailed road map should be the driving step in this regard. There should be a clear articulation of career pathways for family medicine trainees in health systems with the availability of transitional learning opportunities for in-service primary care physicians interested to continue in general practice. Care has to be taken that family medicine does not operate in silos and establishes synergy with Clinical and Preventive Medicine Departments. Further, pertinent interventions to elevate status in the hierarchy of medical specialties should be thoughtfully designed so as to attract more medical students into this discipline. Without such architectural restructuring, realizing the new visions of national health assurance and universal health coverage might prove a daunting goal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Indian Health Care: Inspiring Possibilities, Challenging Journey, Report Prepared for Federation of Indian Industry by Mckinse and Company. (1-34).2012:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.New York: United Nations; 2001. UN. Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations millennium declaration. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy KS. Health assurance: Giving shape to a slogan. Curr Med Res Pract. 2015;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report on “Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage in India”: Confederation on Indian Industry; July. 2014. [Last cited on 2015 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.mycii.in/KmResourceApplication/42087.UHCPaperfinal8July2014.pdf .

- 5.Kollannur A. Will India deliver on universal health coverage? BMJ. 2013;347:f5621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy KS, Patel V, Jha P, Paul VK, Kumar AK, Dandona L. Lancet India Group for Universal Healthcare. Towards achievement of universal health care in India by 2020: A call to action. Lancet. 2011;377:760–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61960-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips WR, Haynes DG. The domain of family practice: Scope, role, and function. Fam Med. 2001;33:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singapore: WONCA; 2002. WONCA (World Organisation for Family Doctors). Improving Health Systems: The Contribution of Family Medicine, A Guide Book. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008 – Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World Health Organization. 2010. [Last cited on 2014 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/index.html .

- 11.Hellenberg DA, Gibbs T, Megennis S, Ogunbanjo GA. Family medicine in South Africa: Where are we now and where do we want to be? Eur J Gen Pract. 2005;11:127–30. doi: 10.3109/13814780509178253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health Policy 2015 Draft. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid = 3014 .

- 13.Ramanayake RP, De Silva AH, Perera DP, Sumanasekara RD, Gunasekara R, Chandrasiri P. Evaluation of teaching and learning in family medicine by students: A Sri Lankan experience. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:3–8. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.152236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pati S, Sharma K, Zodpey S, Chauhan K, Dobe M. Health promotion education in India: Present landscape and future vistas. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:159–67. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n4p159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Membership Application Brochure and Family Medicine Career Development Guide. Academy of Family Physicians of India, Registered Nonprofit Society, Academic Association of Residency Trained Family Physicians in India. A Member Organization of WONCA – World Organization of Family Doctors. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.afpionline.com/documents/afpimembershipguide.pdf .

- 16.Family Medicine-Report of a Regional Scientific Working Group Meeting on Core Curriculum, Colombo, Sri Lanka. [Last cited on 2015 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.apps.searo.who.int/pds_docs/B3426.pdf .

- 17.DNB in Family Medicine (New Rules). National Board of Examinations (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India) [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.natboard.edu.in/notice_for_dnb_candidates/Curriculum_for_DNB_Family_Medicine_New_Rules_UPDATE.pdf .

- 18.Master in Medicine (Family Medicine). Dr. M.G.R. Medical University Through the Mode of – Distance Education. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.web.tnmgrmu.ac.in/regulations/familymedicine.pdf-familymedicine.pdf .

- 19.FCAMS+MDGP | Christian Fellowship Hospital. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.cfhospital.org/fcamsmdg .

- 20.Indian Medical Association. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.imaagra.org/ima-cgp.htm .

- 21.Pathfinder Health India Begins PG Diploma in Family Medicine in New Delhi. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid = 67072 and sid = 2 .

- 22.Post Graduate Diplomas PG Diploma in Family Medicine New Delhi Institute of Health and Management studies | Emagister. [Last cited on 2014 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.emagister.in/pg_diploma_family_medicine_courses-ec2763751.htm .

- 23.Doctor of Medicine in Family Medicine. Chhatrapati Shahu Ji Maharaj Medical University (Under Central Initiative) [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.archive.financialexpress.com/news/md-course-in-family-medicine-on-thecards/721379/1 .

- 24.Master in Medicine in Family Medicine. Christian Medical College Vellore, Department of Distance Education. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.cmch-vellore.edu/pdf/jobs/prospectus%202013.pdf .

- 25.Kumar R. Family medicine at AIIMS (All India Institute of Medical Sciences) like institutes. J Family Med Prim Care. 2012;1:81–3. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.104925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghavan MK. Medical Colleges; Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Starred Question No. 37 Answered on November 23. 2012. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www. 164.100.47.132/LssNew/psearch/QResult15.aspx?qref = 130114 .

- 27.Medical Council of India Regulations on Graduate Medical Education. 1997. [Last cited on 2015 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulation/GME_REGULATIONS.pdf .

- 28.Lawn JE, Rohde J, Rifkin S, Were M, Paul VK, Chopra M. Alma-Ata 30 years on: Revolutionary, relevant, and time to revitalise. Lancet. 2008;372:917–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jayakrishnan T, Honhar M, Jolly GP, Abraham J, Jayakrishnan T. Medical education in India: Time to make some changes. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sankarapandian V, Christopher PR. Family medicine in undergraduate medical education in India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3:300–4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]