Abstract

Objectives: to evaluate orthogeriatric and nurse-led fracture liaison service (FLS) models of post-hip fracture care in terms of impact on mortality (30 days and 1 year) and second hip fracture (2 years).

Setting: Hospital Episode Statistics database linked to Office for National Statistics mortality records for 11 acute hospitals in a region of England.

Population: patients aged over 60 years admitted for a primary hip fracture from 2003 to 2013.

Methods: each hospital was analysed separately and acted as its own control in a before–after time-series design in which the appointment of an orthogeriatrician or set-up/expansion of an FLS was evaluated. Multivariable Cox regression (mortality) and competing risk survival models (second hip fracture) were used. Fixed effects meta-analysis was used to pool estimates of impact for interventions of the same type.

Results: of 33,152 primary hip fracture patients, 1,288 sustained a second hip fracture within 2 years (age and sex standardised proportion of 4.2%). 3,033 primary hip fracture patients died within 30 days and 9,662 died within 1 year (age and sex standardised proportion of 9.5% and 29.8%, respectively). The estimated impact of introducing an orthogeriatrician on 30-day and 1-year mortality was hazard ratio (HR) = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.65–0.82) and HR = 0.81 (CI: 0.75–0.87), respectively. Following an FLS, these associations were as follows: HR = 0.80 (95% CI: 0.71–0.91) and HR = 0.84 (0.77–0.93). There was no significant impact on time to second hip fracture.

Conclusions: the introduction and/or expansion of orthogeriatric and FLS models of post-hip fracture care has a beneficial effect on subsequent mortality. No evidence for a reduction in second hip fracture rate was found.

Keywords: epidemiology, hip fracture, fracture liaison service, orthogeriatrician, osteoporosis, older people

Introduction

Hip fracture patients are at an increased risk of both subsequent fracture and premature death [1, 2]. An estimated 91,500 hip fractures were expected to occur in the UK during 2015, at a cost in excess of £2 billion (including medical and social care) [3]. These data indicate the importance of measures to improve survival and provide better secondary fracture prevention for these patients.

The provision of timely patient care and secondary fracture prevention for hip fracture patients requires considerable multi-disciplinary input and organising such a service is challenging [4]. Data from randomised controlled trials have shown significant reductions in subsequent fracture risk among hip fracture patients on antiresorptive treatment [5]. Despite these data, it is an international phenomenon that contrary to clinical guideline recommendations, the opportunity to assess for osteoporosis and initiate treatment among patients after a fragility fracture remains grossly underutilised [6, 7].

Within this context, fracture liaison services have been introduced in many countries [8, 9] and are recommended by the UK Department of Health as a model of best practice [3]. The British Orthopaedic Association also states that the complex needs of elderly fracture patients are best addressed when an orthogeriatrician is ‘fully integrated into the work of the fracture service’ [3]. However, a recent audit in the UK found only 37% of local health services provided any kind of fracture liaison service (FLS) [7], and significant variation exists in how such services are structured [4, 10]. The clinical effectiveness of such coordinated models of care is emerging [8]; however, data on key clinical outcomes are scarce [11].

The aim of this study is to use a natural experimental approach to estimate the clinical effectiveness of orthogeriatric and nurse-led FLS models of post-hip fracture care on the risk of second hip fracture and mortality after primary hip fracture.

Materials and methods

Information on hip fracture hospital admissions was obtained from the UK hospital episode statistics (HES) database. Mortality data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) were linked and extracted using an encrypted patient identifier.

All patient episodes containing an ICD10-code indicating hip fracture (S72.0, S72.1, S72.2, S72.9) as the primary diagnosis and with a start date occurring within the study period (1st April 2003–31st March 2013) were identified (Supplementary data, Appendix 1, available in Age and Ageing online). Provider codes and treatment site codes were used to identify episodes occurring within the 11 NHS hospitals admitting hip fracture patients in the region of interest.

The primary outcome of interest was time to second hip fracture within 2 years of a primary hip fracture. To ensure this was a separate fracture incident, we counted second hip fractures only if admitted in a separate ‘continuous inpatient spell’ and at least 30 days after admission for the primary fracture. Secondary outcomes of interest were time to death: (i) within 30 days and (ii) within 1 year following a primary hip fracture admission. Sample size calculations for these outcomes are provided in Supplementary data, Appendix 2, available in Age and Ageing online.

The primary exposure (‘intervention’) was the implementation within individual hospitals of specific change to the model of post-hip fracture care. Information on the nature and timing of such changes had been obtained through a detailed evaluation of hip fracture services within the 11 hospitals of interest over the last decade [10]. We approached relevant health professionals within each hospital with a questionnaire we developed to allow the characterisation of pre-specified elements of secondary fracture prevention services over the study period. Interventions were identified prior to statistical analysis (Table 1 and Supplementary data, Appendix 3, available in Age and Ageing online).

Table 1.

Regional summary of primary hip fracture admissions, clinical outcomes and time points of changes to post-hip fracture care model during the study period (financial years 2003/4 to 2012/13)

| Hospital | Primary hip fractures (N) | Age (years)a | Gender (% female) | 2-year secondary hip fractures |

30-day mortality |

1-year mortality |

Timepoints of change to post-hip fracture model of care |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Proportion (%)b | N | Proportion (%)b | N | Proportion (%)b | Nurse-led FLS | Orthogeriatrician | ||||

| 1 | 3,115 | 82.9 (8.3) | 74.8 | 146 | 5.0 | 309 | 10.6 | 949 | 31.3 | – | – |

| 2 | 3,943 | 82.9 (8.2) | 74.2 | 161 | 4.4 | 378 | 9.9 | 1,176 | 30.3 | – | May 2005, Aug 2007 |

| 3 | 1,858 | 82.6 (8.1) | 73.6 | 80 | 4.2 | 178 | 9.7 | 586 | 31.2 | – | – |

| 4 | 2,819 | 82.9 (8.3) | 75.8 | 99 | 4.1 | 242 | 9.3 | 753 | 28.5 | May 2009 | Oct 2006 |

| 5 | 1,837 | 82.8 (8.1) | 73.9 | 56 | 3.4 | 154 | 8.7 | 528 | 29.7 | – | Sept 2009c,d |

| 6 | 1,030 | 82.7 (8.1) | 73.8 | 41 | 4.1 | 60 | 5.5 | 238 | 22.6 | – | Nov 2005e |

| 7 | 5,895 | 82.8 (8.2) | 76.6 | 206 | 3.7 | 489 | 8.8 | 1,687 | 29.2 | June 2007d | July 2004 |

| 8 | 4,937 | 83.0 (8.1) | 74.3 | 191 | 4.0 | 481 | 9.7 | 1,549 | 31.7 | – | March 2009 |

| 9 | 1,994 | 83.1 (8.1) | 75.0 | 76 | 4.2 | 194 | 9.7 | 562 | 28.5 | April 2005 | – |

| 10 | 4,218 | 82.9 (8.3) | 74.1 | 154 | 4.1 | 417 | 9.9 | 1,213 | 28.9 | May 2006, May 2008 | Nov 2009c,d |

| 11 | 1,506 | 82.7 (8.2) | 73.9 | 78 | 5.2 | 131 | 9 | 421 | 29.1 | – | – |

| Whole region | 33,152 | 82.9 (8.2) | 74.8 | 1,288 | 4.2 | 3,033 | 9.5 | 9,662 | 29.8 | ||

aMean (SD).

bAverage proportion, across each financial year under study, of primary hip fracture patients identified as experiencing outcome of interest within the specified time period (e.g. mortality in 30 days) calculated using financial years 2003/4–2011/12 (mortality) and 2003/4–2010/11 (2-year secondary hip fracture). The proportion for each financial year was directly standardised using the age and sex structure of the total primary hip fracture population within each hospital (for hospital-specific proportions) and the region as a whole (for whole region proportion).

cImpact of intervention on hip fracture rate not evaluated due to insufficient post-/pre-intervention data (either owing to another change in service delivery occurring too close to the intervention or the end of study period (given a 1-year lag would need to be used following an intervention to allow it to take effect)).

dImpact of intervention on 1-year mortality rate not evaluated due to significant pre-intervention trend in 1-year mortality rate.

eImpact of intervention on health outcomes not evaluated within hospital 6 (smallest hospital in the region treating hip fractures) due to high variation in annual primary hip fracture admissions during the study period.

Statistical analysis

Survival models were used in a before–after impact analysis. Time to second hip fracture was estimated for the time period after each intervention relative to the time period before. Each hospital was analysed separately (e.g. Supplementary data, Appendix 4, available in Age and Ageing online). Given that a high mortality rate could significantly overestimate the incidence and effect sizes, the competing risk of death was accounted for using Fine and Gray regression modelling. Confounding factors controlled for were age, sex, index of multiple deprivation score and Charlson-comorbidity index (none, mild, moderate and severe). It was decided a priori to exclude from these analyses primary hip fractures admitted within the 12 months after an intervention in order to account for a lagged onset of bone protection therapies, and this excluded 13.3% for the region. Primary hip fracture episodes starting after 31 March 2011 were not included in the evaluations due to insufficient (i.e. less than 2 years) follow-up. The assessment of linear trend over time was carried out using a piecewise Cox proportional hazards model in which linear splines were fitted to quarterly time points in separate sections of the time series. The proportional hazards assumption was checked, using Schoenfeld residuals.

The evaluation of impact on post-fracture mortality was carried out using a similar approach to above, using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression modelling. We recognised an inevitable time lag for a newly appointed orthogeriatrician to effect systematic change in the care of their patients with a hip fracture and estimated this at 3 months, and this excluded 3.3% of patients. Primary hip fracture episodes were removed from the analyses of 30-day and 1-year mortality if admitted after 31 December 2012 or 31 March 2012 respectively so as to allow for sufficient follow-up before the end of the study period.

A fixed-effects meta-analysis was used to pool estimates of impact on each health outcome under study for orthogeriatric and FLS interventions. Estimated impact of interventions with a pre-existing linear trend (P < 0.05) for any of the health outcomes under study was not included in the corresponding meta-analysis of that health outcome in order to address the potential bias of secular trend. Statistical analysis was carried out using the stata v.13.1.

Results

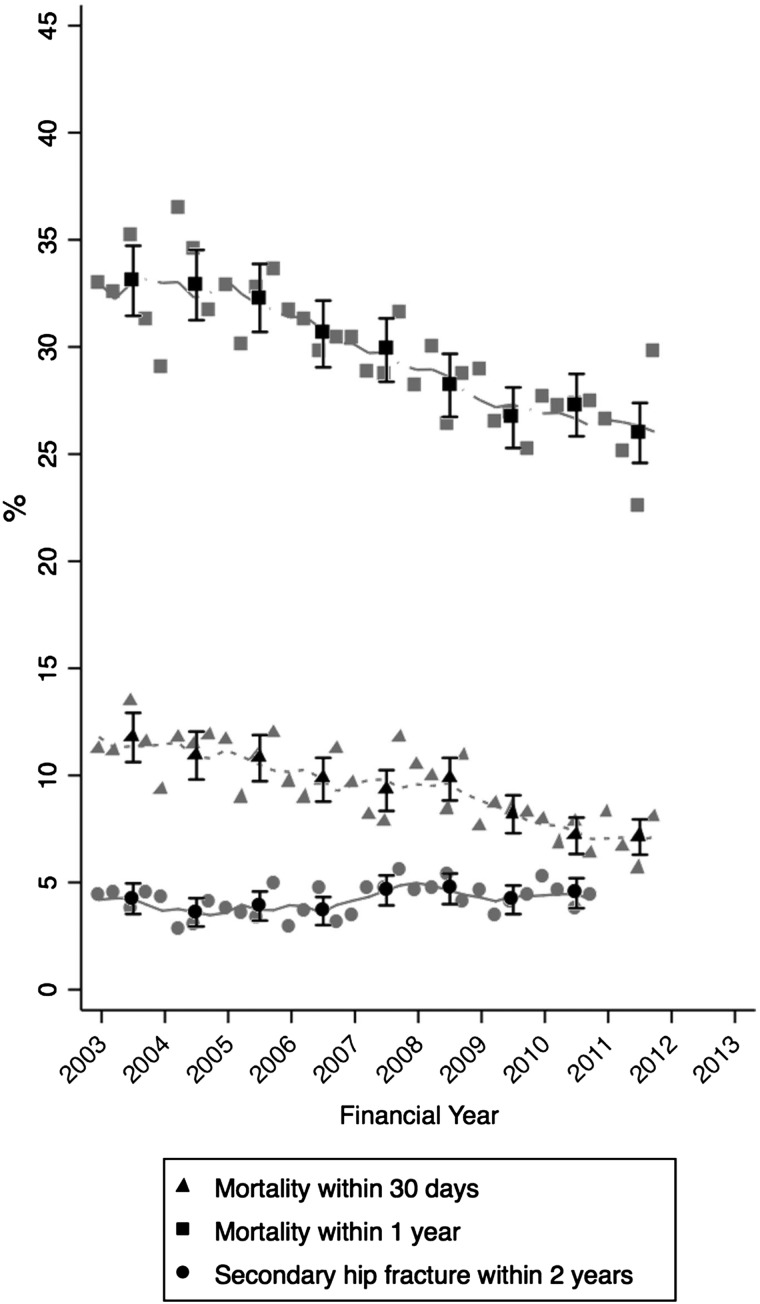

A total of 33,152 hospital episodes were identified as pertaining to a primary hip fracture, ranging from 1,030 to 5,895 per hospital of interest (Table 1). The proportion of female admissions significantly changed over time, decreasing from 78.2% (2003/4) to 72.0% (2012/13). Mean age increased slightly over the study period from 82.7 years (2003/4) to 83.1 years (2012/13). There were 1,288 patients identified as sustaining a second hip fracture within 2 years from a primary hip fracture, at an average directly age- and sex-standardised proportion of 4.2% across financial years studied. This proportion remained stable throughout the study period (P-trend = 0.11). There were 3,033 patients that died within 30 days and 9,662 that died within 1 year from their primary hip fracture (averaged age- and sex-standardised proportion across financial years studied of 9.5% and 29.8%, respectively). Overall, age- and sex-standardised 30-day mortality declined from 11.8% in 2003/4 to 7.1% in 2011/12 (P-trend<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual and quarterly regional trends in mortality (30-day and 1-year) and second hip fracture (2-year) after primary hip fracture during the study period.

Two of the 13 interventions (Table 1 and Supplementary data, Appendix 3, available in Age and Ageing online) could not be analysed in relation to time to second hip fracture owing to insufficient pre- or post-intervention follow-up time once a 12-month lag period was introduced. Three interventions were not evaluated in relation to 1-year post-fracture mortality owing to a pre-intervention trend, i.e. the quarterly rates in outcome before the intervention were not stable.

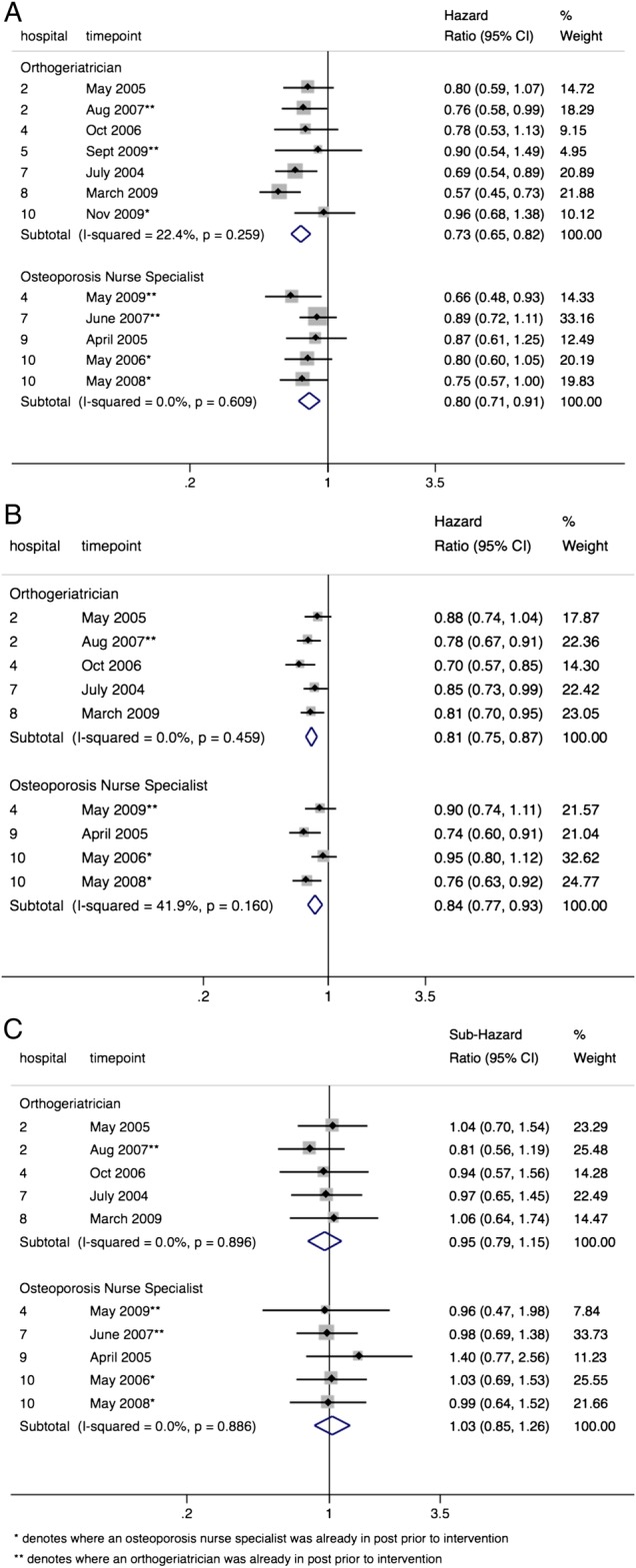

The pooled estimated impact of introducing an orthogeriatrician on 30-day and 1-year mortality was hazard ratio (HR) = 0.73 (CI: 0.65–0.82) and HR = 0.81 (CI: 0.75–0.87), respectively (see Figures 2A and B). Thirty-day and 1-year mortality were likewise reduced following the introduction of an FLS: HR = 0.80 (95% CI: 0.71–0.91) and HR = 0.84 (0.77–0.93), respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for outcomes within each hospital, comparing the time period after relative to the time period before orthogeriatric or FLS service model interventions for (A) mortality within 30 days, (B) mortality within 1 year and (C) second hip fracture following primary hip fracture.

The reductions in mortality were seen whether introducing an orthogeriatric or FLS model of care for the first time or as part of an expansion of an existing service. For example, 1-year mortality was reduced following the appointment of a second orthogeriatrician within hospital 2 in August 2007 compared with service delivery during the time with one orthogeriatrician already in post (HR = 0.78 (95% CI: 0.67–0.91)) (Figure 2B).

Conversely, the sub-hazard ratios (SHRs) from the survival models showed no evidence for an impact on time to secondary hip fracture (Figure 2C) following any of the interventions when analysed separately or when pooled by the type of intervention: orthogeriatrician (SHR = 0.95 (CI: 0.79–1.15) or FLS (SHR = 1.03 (CI: 0.85–1.26).

Discussion

Main findings

Within this study, we observed an overall decline in mortality after primary hip fracture across the region as a whole from 2003 to 2011. Despite this increased survivorship, the rate of second hip fracture remained relatively stable over this time period. We have demonstrated that the introduction and/or expansion of orthogeriatric and FLS models of care is significantly associated with reduced post-hip fracture mortality. Assuming a pre-intervention survival of 90% at 30-days and using the pooled estimates of intervention impact, the number of patients needed to treat (NNT) to avoid 1 excess death at 30-days is 12 and 17 for orthogeriatric and FLS type interventions. Neither orthogeriatric nor FLS interventions here evaluated had any significant impact on time to second hip fracture.

Mortality

We found the average standardised proportion of primary hip fracture patients dying within 30-days and 1-year to be 9.5 and 29.8%, respectively, which is consistent with previous reports in a similar population [12, 13], as is the overall downward trend in mortality after hip fracture here identified during 2003–11 [14].

A beneficial impact on mortality associated with an orthogeriatric model of care is a plausible finding and is in keeping with previous studies [15, 16]. It was reported in the pre-analysis service evaluation that for hospital 8, the appointment of an orthogeriatric clinical lead meant 90% of hip fracture patients were seen pre-operatively for optimisation for surgery and that the appointment of a second orthogeriatrician in hospital 2 led to patients being taken to theatre quicker and in better condition. These are important factors given previous evidence that trauma-related complications play a key role in post-hip fracture mortality [17], and that earlier surgery is associated with lower risk of death [18]. The benefit of geriatric hip fracture care on delirium has also been previously demonstrated [19]. Our findings are consistent with UK NICE clinical guidelines [4] and the British Orthopaedic Association's recommendation that ‘senior medical input from a consultant orthogeriatrician is now essential in the good care of fragility fracture patients’ [3].

The reasons for a reduction in mortality following the introduction and/or expansion of an FLS are not as clear as for the orthogeriatric model, although an FLS is likely to result in an environment of better co-ordination of multi-disciplinary care with better communication between staff. The comprehensive assessment and inspection of routine bloods and medical history that an osteoporosis nurse specialist carries out may likewise contribute to the identification of secondary diseases and comorbidities. The expected increase in bisphosphonate use may also play a role [20]. Previous studies have reported similar findings, there prompting the conclusion that measures to prevent fractures also reduce mortality [20, 21].

Second hip fracture

Our finding of an average standardised proportion of 4.2% for second hip fracture within 2 years of primary hip fracture is in accord with previous studies [22, 23] although direct comparisons are difficult due to different lengths of follow-up time used.

The British Orthopaedic Association states that the most effective healthcare solution for secondary fracture preventative assessment is the Fracture Liaison Service, routinely delivered by a nurse specialist supported by a lead clinician in osteoporosis [3]. Marsh et al. also report that such systems appear to be able to overcome barriers to osteoporosis intervention and treatment [9]. It is surprising therefore to find a null effect on hip re-fracture risk in our study. Although, in general, orthogeriatricians did initiate bone protective therapies and some nurse specialists were able to make treatment recommendations that were later prescribed by doctors, one reason for the lack of observed effect may be patient's inadequate adherence to prescribed therapies. During the period of the study, the interventions analysed focused on identification, investigation and initiation of bone therapy but delegated monitoring to primary care services. However, patients' adherence to osteoporosis therapies within the NHS primary care services is poor, at less than 40% by 12 months [24], and highlights the importance of incorporating monitoring within the scope of a fracture liaison service.

It has been previously noted that the risk of subsequent fracture after hip fracture can be offset by increased post-fracture mortality [25], which has elsewhere been used to explain increasing re-fracture trends during 2000–10 [26]. It is possible that this dependency of fracture risk on mortality may be a contributory factor to the apparent lack of impact on second fracture rate here observed. The high rate of early re-fracture (35 and 63% within the first 6 and 12 months, respectively), combined with the delayed onset of fracture risk reduction associated with therapies recommended or dispensed within the orthogeriatric and FLS models of care here studied may also have played a role. It has been shown elsewhere that an FLS may only impact on fracture outcomes after 15 months [21]; however, in post hoc analyses we found no significant change in pooled estimates of impact on second fracture between 12 and 36 months after index fracture. The clinical effectiveness of the FLS has been previously demonstrated in terms of a trend towards improved bone mineral density testing rates and treatment initiation [8, 9] although data on the most compelling outcomes such as re-fracture rates have been rarely reported [11]. Our study complements other evaluations of FLS initiatives from the USA [27], Scotland [28], Canada [29] and Australia [30].

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present analysis is the use of a natural experimental design where each hospital acted as its own control in a before–after impact analysis. The comprehensive nature of the HES database allowed for case-mix adjustment and a robust definition of primary hip fracture. A priori service evaluation findings provided details on the timing and nature of all major changes to service delivery of post-hip fracture care and secondary fracture prevention during the study period.

Our analysis is subject to various limitations. We were only able to consider second fractures if associated with a separate hospital spell. Also, confounding events may have coincided with interventions of interest although we consider this unlikely given estimates were consistent across hospitals and for interventions at different time points. Secular trend may also have introduced bias into impact estimates; however, this issue was addressed by excluding from analysis interventions that were preceded by a significant trend in respective health outcomes. Given the observational nature of the study, residual confounding may have remained, e.g. through the use of our categorised Charlson score. Furthermore, several aspects of the interventions evaluated were subject to variation (Supplementary data, Appendix 3, available in Age and Ageing online) which we were not able to consider in analyses, indicating the possibility that these various investments might act as proxies for unspecified effects associated with general improvement in the quality of fracture services. Our focus here was on health outcomes after hip fracture, hence our findings may not reflect the effectiveness of these models of care among patients having sustained a non-hip fragility fracture.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that the introduction and/or expansion of orthogeriatric and FLS models of care have a large beneficial effect on subsequent mortality after hip fracture. There was no evidence for a reduction in second hip fracture rate, but the effect on non-hip fracture remains unanswered as these outcomes cannot be ascertained within the secondary care setting of this study.

Key points.

Orthogeriatric and fracture liaison service models of care associated with beneficial impact on subsequent mortality.

There was no evidence for a reduction in the rate of second hip fracture.

Impact among non-hip fracture patients and on subsequent non-hip fracture outcomes remains unanswered.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Conflicts of interest

M.K.J., D.P.-A., J.L., N.K.A., C.C. and A.J. received grants from NIHR HS&DR during the conduct of the study. Outside the submitted work M.K.J. reports personal fees from Lilly UK, Amgen, Sevier, Merck, Medtronic, Internis, Consilient Health; D.P.-A. received grants from Bioiberica S.A. and Amgen Spain S.A.; N.K.A. received grants and personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Merck, Smith and Nephew, Q-Med, Nicox, Flexion, Bioiberica and Servier; C.C. received personal fees from Servier, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Medtronic and Novartis. A.J. has received consultancy, lecture fees and honoraria from Servier, UK Renal Registry, Oxford Craniofacial Unit, IDIAP Jordi Gol, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer has held advisory board positions (which involved receipt of fees) from Anthera Pharmaceuticals, INC., and received consortium research grants from ROCHE. In addition, M.K.J. serves on the Scientific Committee of the National Osteoporosis Society and International Osteoporosis Foundation. S.H. and S.S. have no competing financial interests relevant to the submitted work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme (HS&DR) (project number 11/1023/01); and from the Oxford NIHR Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit and Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, University of Oxford. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The HES data were made available by the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre. Copyright © 2013, re-used with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved. We thank all the members of the FRiSCy group for contributing their time and expertise. S.H. and A.J. had full access to all of the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors revised and approved the final version of the article. A.J. and M.K.J. supervised the study and are joint senior authors. The ReFRESH study group consists of A.J., M.K.J., N.K.A., C.C., Prof. Andrew Farmer, D.P.-A, Dr Jose Leal, Prof. Michael Goldacre, Prof. Alastair Gray, J.L., Dr Rachael Gooberman-Hill and Laura Graham.

References

- 1.Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 2009; 20: 1633–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper C, Mitchell P, Kanis JA. Breaking the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 2049–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The care of patients with fragility fractures. British Orthopaedic Association, 2007.

- 4.Chesser TJ, Handley R, Swift C. New NICE guideline to improve outcomes for hip fracture patients. Injury 2011; 42: 727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS et al. . Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD. Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006; 35: 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremi J, Lowe D, Vasilakis N. Falling standards, broken promises: Report of the national audit of falls and bone health in older people. Royal College of Physicians, 2011.

- 8.Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS et al. . Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2013; 24: 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsh D, Akesson K, Beaton DE et al. . Coordinator-based systems for secondary prevention in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 2051–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drew S, Sheard S, Chana J et al. . Describing variation in the delivery of secondary fracture prevention after hip fracture: an overview of 11 hospitals within one regional area in England. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25: 2427–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sale JE, Beaton D, Posen J, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch E. Key outcomes are usually not reported in published fracture secondary prevention programs: results of a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014; 134: 283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2005; 331: 1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts SE, Goldacre MJ. Time trends and demography of mortality after fractured neck of femur in an English population, 1968–98: database study. BMJ 2003; 327: 771–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klop C, Welsing PM, Cooper C et al. . Mortality in British hip fracture patients, 2000–2010: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Bone 2014; 66: 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabharwal S, Wilson H. Orthogeriatrics in the management of frail older patients with a fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int 2015; 26: 2387–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeltzer J, Mitchell RJ, Toson B, Harris IA, Ahmad L, Close J. Orthogeriatric services associated with lower 30-day mortality for older patients who undergo surgery for hip fracture. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 409–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture-effect of pre-morbid conditions and post-fracture complications. Osteoporos Int 2007; 18: 1583–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simunovic N, Devereaux PJ, Sprague S et al. . Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2010; 182: 1609–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huntjens KMB, van Geel TCM, Geusens PP et al. . Impact of guideline implementation by a fracture nurse on subsequent fractures and mortality in patients presenting with non-vertebral fractures. Injury 2011; 42: S39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huntjens KM, van Geel TA, van den Bergh JP et al. . Fracture liaison service: impact on subsequent nonvertebral fracture incidence and mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96: e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence TM, Wenn R, Boulton CT, Moran CG. Age-specific incidence of first and second fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92: 258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapurlat RD, Bauer DC, Nevitt M, Stone K, Cummings SR. Incidence and risk factors for a second hip fracture in elderly women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Osteoporos Int 2003; 14: 130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Roddam A, Gitlin M et al. . Persistence with osteoporosis medications among postmenopausal women in the UK General Practice Research Database. Menopause 2012; 19: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR, Arora T, Matthews RS et al. . Is withholding osteoporosis medication after fracture sometimes rational? A comparison of the risk for second fracture versus death. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010; 11: 584–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson-Smith D, Klop C, Elders PJM et al. . The risk of major and any (non-hip) fragility fracture after hip fracture in the United Kingdom: 2000–2010. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25: 2555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90(Suppl 4): 188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA et al. . Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 2083–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH et al. . Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture—results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 2110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lih A, Nandapalan H, Kim M et al. . Targeted intervention reduces refracture rates in patients with incident non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures: a 4-year prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.