Abstract

Increased cerebral blood flow has been shown to induce pathological structural changes in the Circle of Willis (CoW) in experimental models. Previously, we reported flow-induced aneurysm-like remodeling in the CoW secondary to flow redistribution after bilateral common carotid artery (CCA) ligation in rabbits. In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that loading rabbits with biological risk factors for vascular disease would increase flow-induced aneurysmal remodeling in the CoW. In the same series as the previously-reported bilateral CCA-ligation-alone (n=6) and sham surgery (n=3) groups, eight additional female rabbits (the experimental group in this study) were subjected to two risk factors for intracranial aneurysm (hypertension and estrogen deficiency) and then bilateral CCA ligation. Upon euthanasia at 6 months, vascular corrosion casts of the CoW were created and analyzed by scanning electron microscopy for morphological changes and aneurysmal damage. In rabbits with hypertension and estrogen deficiency, arterial caliber increased throughout the CoW, similar to rabbits with CCA ligation alone. However, aneurysmal remodeling (i.e. local bulging) in the CoW was significantly greater than in CCA-ligation-only rabbits and was more widespread, presenting in regions that did not show aneurysmal changes after CCA ligation alone. Furthermore, hypertension and estrogen deficiency caused greater increases in vessel length and tortuosity. These results suggest that hypertension and estrogen deficiency make the CoW more vulnerable to flow-induced aneurysmal remodeling and tortuosity. We propose they do so by lowering the tolerance of vascular tissue to hemodynamic forces caused by CCA ligation, thus lowering the threshold necessary to incite vascular damage.

Keywords: Arterial tortuosity, carotid artery ligation, aneurysm risk factors, de novo intracranial aneurysm, aneurysm initiation

Introduction

Increased hemodynamic forces can induce pathological cerebrovascular remodeling, including the genesis of intracranial aneurysms (IAs).(Meng et al., 2013) To investigate the effect of hemodynamic insult on IA pathogenesis, we previously established a rabbit IA model, in which bilateral common carotid artery (CCA) ligation alone consistently resulted in de novo aneurysmal damage at the basilar terminus (BT).(Metaxa et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2011) The aneurysmal remodeling, characterized by internal elastic lamina loss, medial thinning, and bulging was localized to peri-apical regions of the bifurcation where altered blood flow due to CCA ligation produced abnormally high hemodynamic forces on the vessel wall.(Metaxa et al., 2010; Kolega et al., 2011; Mandelbaum et al., 2013) To further inquire whether carotid ligation would elicit pathological remodeling elsewhere in the cerebral vasculature, we recently analyzed vascular corrosion casts of the entire CoW from rabbits subjected to bilateral carotid ligation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the casts showed widespread pathological remodeling (aneurysmal changes and arterial tortuosity) in anterior and posterior regions 6 months after ligation.(Tutino et al., 2013) Taken together, these studies demonstrated that hemodynamic insult to the CoW by carotid ligation leads to de novo aneurysmal remodeling in otherwise healthy animals.

In addition to hemodynamics,(Meng et al., 2013) other factors that are associated with IA development, such as hypertension, female gender, family history, and smoking,(Cebral and Raschi, 2012) have been identified through epidemiologic studies. For example, hypertension is present in 43.5% of IA patients vs. 24.4% of the general population,(Inci and Spetzler, 2000) and menopause in women - who make up three quarters of IA patients (Wiebers et al., 2003) - also increases the predisposition for IA.(Harrod et al., 2006) Effects of both hypertension and estrogen deficiency are well established in experimental studies that have incorporated IA risk factors into animal models of aneurysm. Hypertension by renal infarction (Nagata et al., 1980; Hashimoto et al., 1984) and by high salt diet plus deoxycorticosterone treatment (Hashimoto et al., 1978, 1979) has been used to increase incidence of IA formation in rat models. Furthermore, estrogen deficiency via bilateral oophorectomy in a rat model of IA has been shown to increase aneurysm presentation,(Jamous et al., 2005a) while hormone replacement in these rats was shown to ameliorate IA formation.(Jamous et al., 2005b)

While these biological risk factors increased aneurysm frequency, it is important to note that some additional hemodynamic element appears to be necessary, and a manipulation to cerebral blood flow, typically by unilateral CCA ligation, has always been incorporated into animal models of IA initiation. In fact, Coutard showed that in the absence of hemodynamic manipulation, the induction of IA risk factors alone was unable to incite IA initiation even in genetically pre-disposed animals.(Coutard, 1999) These observations suggest an interaction between biological risk factors and hemodynamic forces during the genesis of aneurysms. However, the nature of this interaction is not well understood. We hypothesize that biological risk factors for IA make the vasculature more susceptible to hemodynamically-induced aneurysmal remodeling. In this study, we test this hypothesis by loading a cohort of rabbits with two biological risk factors, inducing both hypertension and estrogen deficiency, and then subjecting them to bilateral CCA ligation to increase blood flow to the CoW through the basilar artery (BA). After 6 months, we examined if these biological factors augmented flow-induced aneurysmal changes in the CoW. As in our recent study,(Tutino et al., 2013) we performed vascular corrosion casting and imaging by SEM, followed by quantification of gross morphology and aneurysmal changes. This group of rabbits served as the experimental group and was compared against our 6-month carotid-ligation-only group and a sham-operated group, both of which were created at the same time as the experimental group but have been described in a previous publication.(Tutino et al., 2013)

Materials and Methods

Induction of hypertension, estrogen deficiency, and flow increase

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the State University of New York at Buffalo. Eight adult female New Zealand White rabbits (4-5 Kg) were loaded with IA risk factors by being subjected to both unilateral nephrectomy and bilateral oophorectomy, manipulations that have been shown to induce hypertension (Ht) (Areas et al., 1991) and estrogen deficiency (ED) in rabbits,(Hansen et al., 1996) respectively. To intensify hypertension we also placed the rabbits on a high salt diet. Two weeks after surgery we subjected the rabbits to bilateral CCA ligation. These 8 rabbits, identified as the ligation + HtED group, were compared to our previously-reported rabbits in the same series that received ligation only (n=6) and a sham surgery as control (n=3).(Tutino et al., 2013)

For surgery, anesthesia was initiated by intramuscular injection of 35 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine, after which animals were maintained with 2% isoflourane gas. To induce hypertension, the left kidney was accessed through a 3 inch midline incision in the abdomen. The renal artery, renal vein and ureter were ligated using a 3-0 Braunamid suture, and the kidney was excised. Next, both ovaries and the horns of the uterus were isolated, and all arteries and veins of the ovaries and uterine horns were ligated with 3-0 Braunamid suture. The ovaries and uterine horns were removed, the uterine stump was ligated using 3-0 silk suture, and an abdominal closure was performed. One week after the procedure, rabbits were given 1% sodium chloride in their water to add strain on the right kidney. Rabbit blood pressure was measured while the animals were awake with a SurgiVet vitals monitoring device (SIMS BCI Inc., Waukesha, WI, USA) approximately 30 days before and approximately 60 days after surgery. Average blood pressure increased from 92±11 to 133±17 (p=0.033, one-tailed Mann-Whitney U-Test). All rabbits were given at least 2 weeks to recover from surgery. When the rabbits started eating and drinking normally, they were subjected to bilateral CCA ligation to increase flow through the BA, as described in detail elsewhere.(Gao et al., 2008)

Vascular corrosion casting and SEM imaging

Six months after CCA ligation, the rabbits were euthanized by intravenous injection of 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital. Immediately thereafter, we preformed vascular corrosion casting on the entire CoW of all rabbits with Batson's No. 17 Corrosion Casting Kit (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA), as described elsewhere.(Reidy and Levesque, 1977; Tutino et al., 2013) To investigate gross morphological, macroscopic and microscopic properties of the CoW, the endocasts were imaged using a Hitachi SU-70 SEM scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc., Roslyn Heights, NY, USA). Mosaic SEM images of the entire CoW at 50 x were created using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and areas of interest were imaged at higher magnification.

Cerebral vessel diameter, length, and tortuosity measurements

To assess the gross morphology of the CoW, arterial diameters and lengths were measured on mosaic SEM images using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) as described previously.(Tutino et al., 2013) A recognized tortuosity index that normalizes the difference between vessel arc length (L) and chord distance (C) to the chord distance (TI = (L-C)/C) (Hoi et al., 2008) was used to evaluate tortuosity in the proximal and distal P1 segments of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and the PCom (the only available arteries with identifiable beginnings and endings).

Quantitation of vascular damage throughout the CoW

We assessed the prevalence of aneurysmal damage in the new ligation + HtED cohort by measuring the incidence of two previously-described aneurysmal lesions: preaneurysmal bulges and segmental dilations.(Tutino et al., 2013) The incidence and distribution of these lesions were compared to the cohorts of ligated-only and sham-surgery groups.(Tutino et al., 2013) We further quantified the total degree of vascular damage (not limited to aneurysmal lesions) throughout the CoW (see the circled regions of interest in Figure 1). Damage quantitation was accomplished by 3 blinded observers using the previously-reported Vascular Damage Score (VDS).(Tutino et al., 2013)

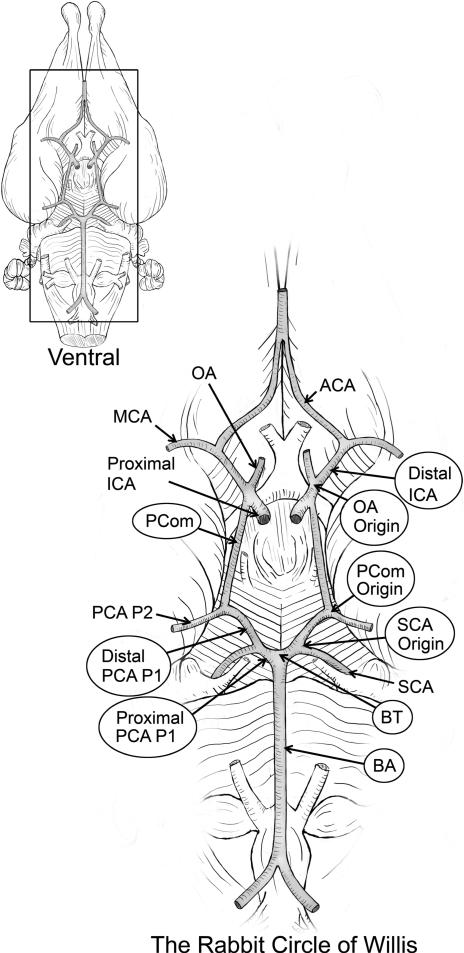

Figure 1.

The rabbit Circle of Willis (CoW). An illustration of the CoW showing the 9 arterial regions (circled) where quantitative properties were assessed.

Statistical analysis

Measurements of gross morphology and vascular damage between groups were compared by a Student's t-test (p < 0.05). All values are expressed as mean ± standard error.

Results

Hypertension and estrogen deficiency in CCA-ligated rabbits affects the morphology of the CoW

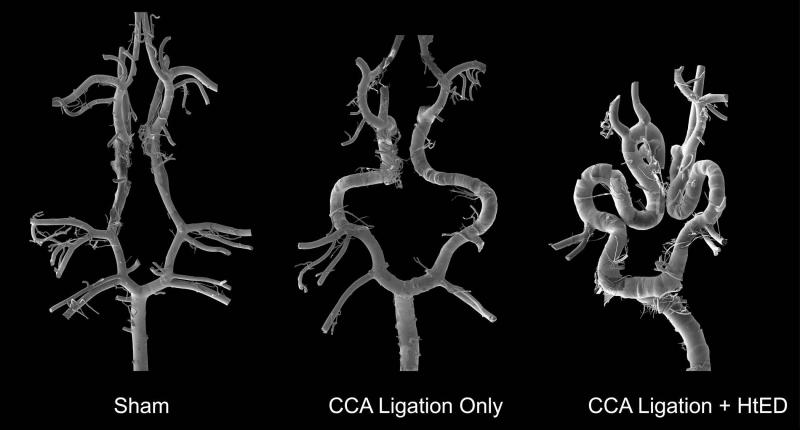

The mosaic SEM images of the rabbit CoW casts revealed that the addition of hypertension and estrogen deficiency changed the CoW morphology compared to those with CCA-ligation only (Fig. 2). Overall, the ligation + HtED group presented increased vascular tortuosity as well as increased aneurysmal lesions.

Figure 2.

Representative mosaic scanning electron micrographs of Circle of Willis (CoW) corrosion casts from the sham, ligation only, and ligation + HtED rabbits. These mosaics demonstrate increased vascular tortuosity and increased aneurysmal lesions in the ligation + HtED group.

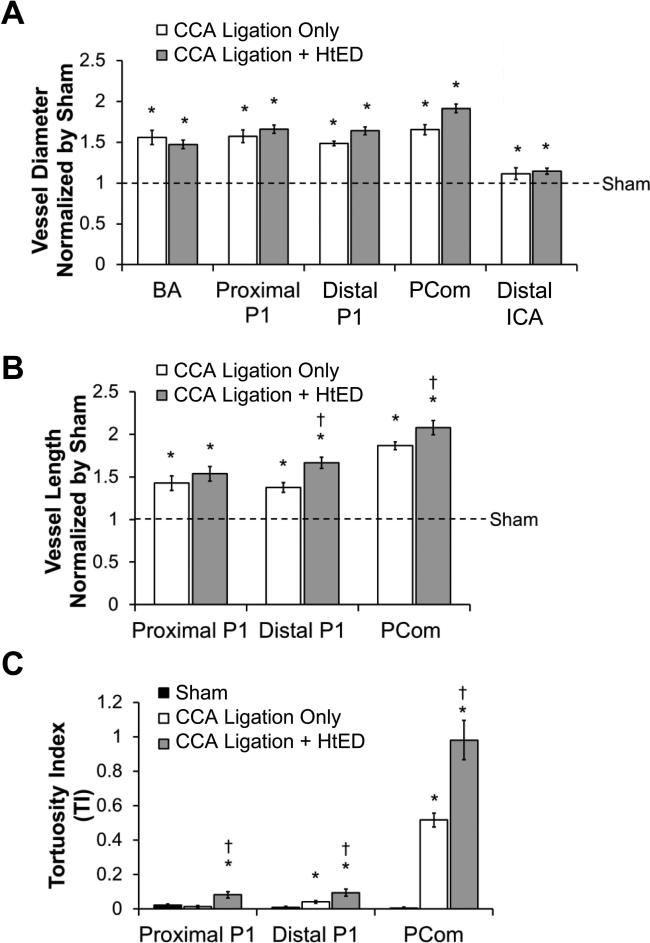

The morphological changes are quantified in Figure 3. The CCA ligation + HtED rabbits had significantly increased vascular diameter, length, and tortuosity compared to the sham group. However, they did not have significantly changed vessel diameters when compared to the previous group with only CCA ligation (Fig. 3a). Compared to the ligation-only rabbits, the ligation + HtED group did have greater increases in distal P1 and PCom lengths (19±5%, p=0.002 and 11±5%, p=0.04, respectively), and greater increases in tortuosity in the proximal P1, distal P1, and PCom (463±125%, p=0.0023; 126±50%, p=0.03; and 90±22%, p=0.0017, respectively) (Fig. 3b and c).

Figure 3.

Effects of hypertension and estrogen deficiency on Circle of Willis morphology. a). The groups with ligation had significantly larger vessel diameters compared to sham. However, vessel diameters in ligation + HtED casts increased to the same extent compared to the ligation only group. b). The lengths of the distal posterior cerebral artery (PCA) P1 and the posterior communicating artery (PCom) were larger in the ligation + HtED casts, compared to the ligation only casts. c). Tortuosity on the proximal P1, distal P1 and PCom was significantly increased in ligation + HtED casts, vs. the ligation only group. * p<0.05 compared with sham casts, † p<0.05 compared with ligation only casts.

Hypertension and estrogen deficiency augments aneurysmal development in CCA-ligated rabbits

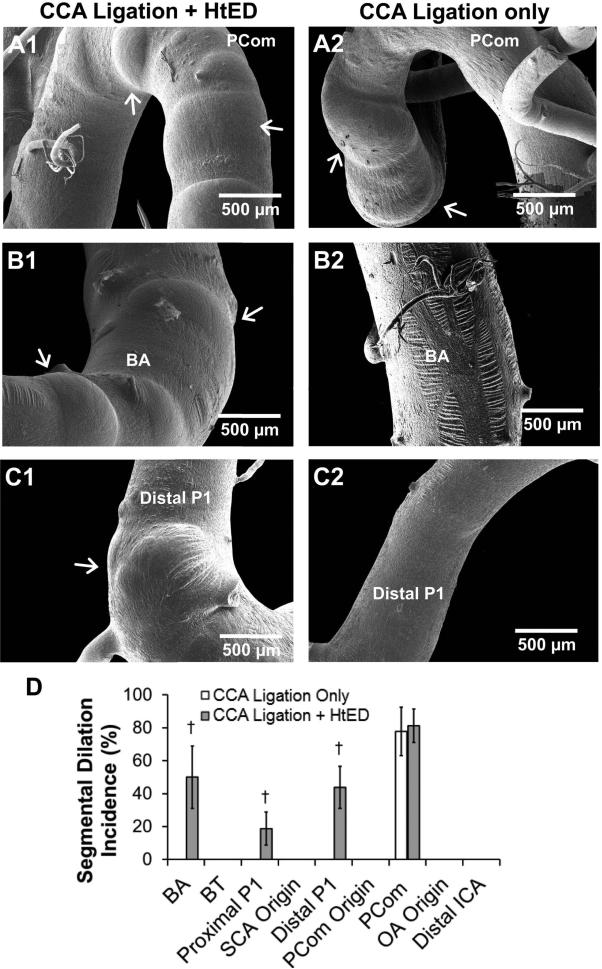

In addition to overall changes in gross morphology of the CoW, the ligation + HtED rabbits also developed localized aneurysmal changes. These changes included asymmetric out-pouchings typically at bifurcation apices (Fig. 4 right column), and circumferential expansions typically along tortuous vessels (Fig. 5 right column). We termed these two types of aneurysmal changes pre-aneurysmal bulges and segmental dilations, respectively.(Tutino et al., 2013)

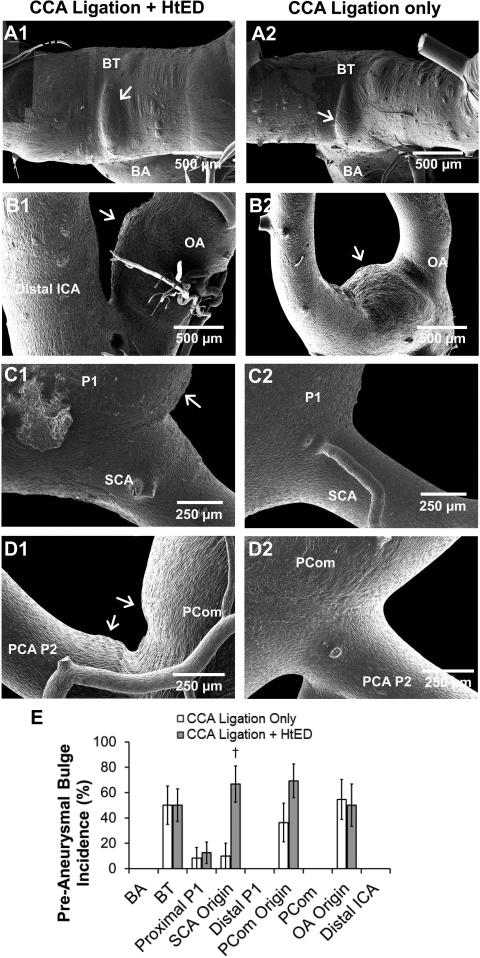

Figure 4.

Presentation of pre-aneurysmal bulges. Left column: ligation + HtED. Right column: ligation only. a). Ophthalmic artery (OA) origin; pre-aneurysmal bulges at the OA origin in ligation + HtED rabbits presented similarly to those in ligation only group. b). Basilar Terminus (BT); pre-aneurysmal bulges at the BT in ligation + HtED rabbits also presented similarly to those in ligation only group. c). Superior cerebellar artery (SCA) origin; ligation + HtED casts had more frequent pre-aneurysmal bulges on the SCA origin, vs. ligation only casts (e). d). Posterior communicating artery (PCom) origin; pre-aneurysmal bulges presented more frequently at the PCom origin of ligation + HtED rabbits compared to the ligation only group, albeit not significantly more (e). † p<0.05 compared with ligation only casts.

Figure 5.

Presentation of segmental dilations. Left column: ligation + HtED. Right column: ligation only. a). Posterior communicating artery (PCom); segmental dilations on the PComs of ligation + HtED rabbits presented similarly to those in ligation only group. b). Basilar artery (BA); ligation + HtED rabbits had more segmental dilations on the BA than the ligation only group (d). c). Posterior cerebral artery (PCA); ligation + HtED rabbits had more segmental dilations on the proximal and distal P1 segment of the PCA compared to ligation only rabbits (d). † p<0.05 compared with ligation only casts.

Figure 4 demonstrates pre-aneurysmal bulges for the ligation + HtED group in comparison to the group with ligation only. At the BT and OA origin, pre-aneurysmal bulges presented with similar frequencies in both groups (Fig. 4a and b). However, the ligation + HtED group had significantly more pre-aneurysmal bulges at the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) origin (67±14 % incidence) than the ligated only group (10±10 % incidence, p=0.0041) (Fig. 5c and e). At the PCom origin, ligation + HtED rabbits also showed increased pre-aneurysmal bulges, albeit not significantly (69%±13 incidence, p=0.12) (Fig. 5d and e). This type of damage was not present in sham casts.

Figure 5 demonstrates segmental dilation for the ligation + HtED group compared to the group with ligation only. At the PCom, segmental dilations presented with similar frequency in both groups (Fig. 5a). However, the ligation + HtED presented significantly increased segmental dilations on the BA (50±19 % incidence), proximal P1 (19±10 % incidence), and distal P1 (44±13 % incidence) vs. ligated only casts, which had 0% incidence at all 3 regions (p=0.033, p=0.083 and p=0.0038, respectively) (Fig. 5b, c, and d). This type of damage was not present in sham casts.

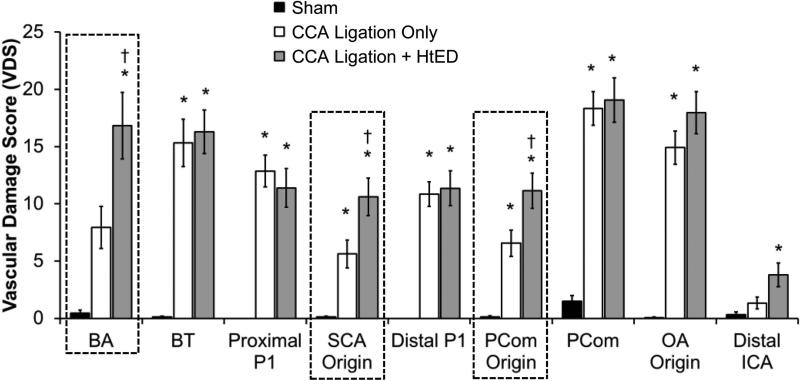

Hypertension and estrogen deficiency increases aneurysmal responses in regions that are less affected by flow increase alone

To further assess the effect of hypertension and estrogen deficiency on aneurysmal development in the CoW globally, we quantified vascular damage in 9 different regions in the CoW, and compared the Vascular Damage Score (VDS)(Tutino et al., 2013) against that measured in the ligation only rabbits.(Tutino et al., 2013) The 9 arterial regions were the BA, BT, proximal PCA P1 (proximal P1), SCA origin, distal PCA P1 (distal P1), PCom origin, PCom, OA origin, and distal ICA (Fig. 1). The VDS grading system ranked vascular damage, from the microscopic scale (endothelial cell irregularities, internal elastic lamina fenestrations, and smooth muscle cell imprints)(Tutino et al., 2013) to the macroscopic scale (pre-aneurysmal bulging and segmental dilations), accommodating for the incidence of each type of damage.(Tutino et al., 2013)

Compared to ligation-only rabbits, the ligation + HtED group had significantly higher VDS in 3 regions: the BA (16.8±2.9 vs 7.8±1.8, p=0.025), the SCA origin (10.6±1.6 vs 5.6±1.2, p=0.025), and the PCom origin (11.1±1.5 vs 6.6±1.2, p=0.031) (Fig. 6). A closer examination of the VDS in each case revealed that the increased scores in these regions of the ligation + HtED group were mostly due to increased aneurysmal development. In the other regions of the CoW, there were no significant differences in the VDS between the two ligated groups.

Figure 6.

Hypertension and estrogen deficiency augment overall flow-induced vascular damage in the Circle of Willis. In ligation + HtED casts the Vascular Damage Score (VDS) was increased at the BA, the SCA origin, and the PCom origin (highlighted by a dashed line) when compared to ligation only casts. This was because of increased incidence of aneurysmal lesions. At regions that previously presented aneurysmal changes (i.e. the BT, PCom, and OA origin) there was no change in VDS between the ligation + HtED and ligation only groups. * p<0.05 compared with sham casts, † p<0.05 compared with ligation only casts.

Discussion

We increased biological risk factors in a previously established rabbit model of flow-induced IA formation by subjecting the animals to both hypertension and estrogen deficiency. In a phenomenological manner, we investigated the effect of these biological factors on flow-induced adaptive and pathological remodeling in the CoW. Our data show that while the cerebral vessels universally increased their calibers after the ligation, there was no significant difference in caliber between animals with and without the added manipulations. This caliber enlargement is an adaptive vascular response that compensates for chronically elevated blood flow through the BA in order to normalize increased wall shear stresses.(Langille, 1996; Lehoux et al., 2002; Hoi et al., 2008) Thus, it seems that hypertension and estrogen deficiency do not have an effect on adaptive remodeling in response to carotid ligation.

Nonetheless, the addition of hypertension and estrogen deficiency significantly augmented the increase in vessel length and tortuosity, as well as the development of localized aneurysmal changes in the CoW following carotid ligation. These vascular changes have been previously identified as pathological or maladaptive remodeling.(Tutino et al., 2013) Interestingly, the addition of hypertension and estrogen deficiency did not increase aneurysmal remodeling in regions that were previously shown to have aneurysm development in animals with CCA ligation alone (the BT, PCom, and OA origin). It did, however, induce aneurysmal changes in new vascular regions in the CoW (the BA, PCA P1, and SCA origin). Hypertension and estrogen deficiency presumably have uniform affect across the entire CoW, raising the question of why aneurysmal damage was increased only in these new locations and not the old regions. Noting that the distribution of hemodynamic forces is not likely to be uniform through the CoW, we suspect that the answer lies in the interaction between biological factors and ligation-induced flow changes.

Metaxa et al. demonstrated that aneurysmal remodeling at the rabbit BT occurs when hemodynamic forces exceed certain levels.(Metaxa et al., 2010). Specifically, detailed hemodynamics–histology mapping showed that IA initiation at the BT (defined by regions of IEL loss) was co-localized with high wall shear stress and positive wall shear stress gradient above a certain threshold.(Metaxa et al., 2010) We propose that hypertension and estrogen deficiency act to lower the threshold for flow-induced damage. Rabbits that have received the additional manipulations to induce hypertension and estrogen deficiency may have a lower threshold throughout the CoW, so that upon carotid ligation, more locations are now subjected to above-threshold hemodynamic insults, and thus new regions develop aneurysmal remodeling. At locations that display damage in the absence of hypertension and estrogen deficiency, the hemodynamic insult is already above the threshold for damage, so no new damage is seen in the ligation + HtED animals.

Hypertension is well known to increases the presence of aneurysmal remodeling in other animal models of IA.(Nagata et al., 1980; Hashimoto et al., 1984) This could be because hypertension produces morphological and functional endothelial cell damage.(Susic, 1997; Inci and Spetzler, 2000) Hypertension has been shown to increase permeability of the endothelium in experimental models (Gabbiani et al., 1979) and to increase matrix metalloproteinase expression in ex vivo experiments.(Chesler et al., 1999) Furthermore, autopsy studies have also demonstrated medial smooth muscle cell necrosis in the cerebral vessels of patients with hypertension.(Masawa et al., 1994) In a rat model of aneurysm, Nagata et al. observed a greater incidence of aneurysmal lesions associated with higher blood pressures in hypertensive rats after unilateral carotid ligation.(Nagata et al., 1980) Our observation that ligation + HtED had greater pre-aneurysmal bulges (lesions that have been associated with IEL loss in our previous studies)(Tutino et al., 2013) is consistent with those finding.

In addition to pre-aneurysmal bulges, ligation + HtED rabbits had increased vessel length and tortuosity in the CoW. Clinically, cerebrovascular tortuosity has been associated with the degree of hypertension.(Hiroki et al., 2002) While the natural history of abnormal vascular tortuosity remains relatively unknown, elevated intraluminal pressure due to hypertension may play a key role in its genesis. Han et al. recently proposed a mechanism of vascular tortuosity formation, in which elevated pulsatile pressure and vessel weakening contribute to arterial buckling, leading to asymmetric vessel remodeling and eventually vascular tortuosity.(Han, 2012) Our findings correlating the induction of hypertension and estrogen deficiency with increased vessel tortuosity may support this hypothesis.

Estrogen deficiency has also been shown to contribute to IA formation in animal models,(Jamous et al., 2005a; Jamous et al., 2005b) and even contribute to higher rates of aneurysm rupture in a mouse IA rupture model.(Tada et al., 2014) Under normal conditions, estrogen enhances endothelial cell function through the release of nitric oxide, which is a vasoprotective molecule important for regulating vascular tone, dilation, and cell growth, as well as for protecting vessels from inflammation and injury.(Cannon, 1998; Gewaltig and Kojda, 2002) Estrogen has also been shown to stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cells, reduce oxidative stress, enhance smooth muscle cell function, inhibit matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9, and inhibit the vascular damage response.(Crowe and Brown, 1999; Wagner et al., 2001; Chambliss and Shaul, 2002) Thus, estrogen deficiency may reduce matrix production and cell renewal, and increase oxidative stress, matrix degradation, inflammation, and tissue damage. Indeed, in a rat IA model (unilateral CCA ligation + HtED) similar to the one presented here, the addition of bilateral oophorectomy was also shown to produce a significantly higher rate of aneurysm formation at the rat anterior cerebral artery-olfactory artery bifurcation.(Jamous et al., 2005a).

It is clear that there are mechanisms by which either hypertension or estrogen deficiency could make the CoW more susceptible to hemodynamic insult. The present study demonstrates that the combination of both factors increases aneurysmal damage and development of tortuosity, but does not attempt to delineate the individual contributions of each risk factor alone. Future studies manipulating risk factors separately in the bilateral CCA ligation model will be needed to determine more precisely how these biological factors interact with flow-induced elements during remodeling.

Our results confirm some clinical findings on the formation of de novo IAs in certain scenarios. Carotid ligation has been a therapeutic option for treating complex IAs that are symptomatic, giant, or cavernous and cannot be treated by microsurgical or endovascular approaches.(Arambepola et al., 2010) The formation of de novo IAs in regions of the CoW contralateral to the ligation has been reported as one potential adverse effect of the procedure (Arnaout et al., 2012) effecting approximately 4.3% of those receiving ligation treatment.(Arambepola et al., 2010) Clinical case reports have provided evidence that changes in cerebral blood flow subsequent to carotid ligation are associated with the genesis of de novo IAs.(Fujiwara et al., 1993; Timperman et al., 1995; Suzuki et al., 2011; Arnaout et al., 2012) Our observation of pre-aneurysmal bulge formation and high VDS in the posterior CoW in ligated rabbits (with or without additional biological risk factors) indicate that such suddenly altered flow can indeed incite vascular remodeling resembling aneurysm initiation.

Conclusion

We performed bilateral CCA ligation in rabbits that had undergone induction of hypertension and estrogen deficiency in order to assess how these systemic factors affect flow-induced vascular remodeling. Hypertensive and estrogen deficient rabbits demonstrated more widespread flow-induced aneurysmal damage and greater increase in vessel length and tortuosity after carotid ligation than rabbits with ligation alone. Yet, hypertension and estrogen deficiency did not affect the global enlargement of vessel caliber, which may be a compensative response to restore appropriate blood distribution when the carotid arteries are blocked. We propose that biological IA risk factors, such as hypertension and estrogen deficiency, lower thresholds for vascular damage in the CoW, enabling more widespread instances of local aneurysmal damage.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant number (R01NS064592). We gratefully acknowledge Peter Bush for SEM instrumentation assistance and Christopher Martensen, Jessica Utzig and Kaitlynn Olczak for help with mosaic SEM image grading.

List of Abbreviations

- BA

basilar artery

- BT

basilar terminus

- CCA

common carotid artery

- CoW

Circle of Willis

- HtED

hypertension and estrogen deficiency induction

- IA

intracranial aneurysm

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- OA

ophthalmic artery

- PCA

posterior cerebral artery

- PCom

posterior communicating artery

- SCA

superior cerebellar artery

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- VDS

vascular damage score

Literature Cited

- Arambepola PK, McEvoy SD, Bulsara KR. De Novo Aneurysm Formation after Carotid Artery Occlusion for Cerebral Aneurysms. Skull Base-Interdiscip Appr. 2010;20:405–408. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areas JL, Enriquez DA, Newsome J, MacArthy P, Yousufi AK, Preuss HG. Blood pressure in unilaterally nephrectomized rabbits: a correlation with serum renotropic activity. Nephron. 1991;58:339–343. doi: 10.1159/000186447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaout OM, Rahme RJ, Aoun SG, Daou MR, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. De novo large fusiform posterior circulation intracranial aneurysm presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage 7 years after therapeutic internal carotid artery occlusion: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:E764–771. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31825fd169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon RO., 3rd. Role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular disease: focus on the endothelium. Clinical chemistry. 1998;44:1809–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebral JR, Raschi M. Suggested Connections Between Risk Factors of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Review. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0723-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambliss KL, Shaul PW. Estrogen modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Endocrine reviews. 2002;23:665–686. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler NC, Ku DN, Galis ZS. Transmural pressure induces matrix-degrading activity in porcine arteries ex vivo. The American journal of physiology. 1999;277:H2002–2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutard M. Experimental cerebral aneurysms in the female heterozygous Blotchy mouse. International journal of experimental pathology. 1999;80:357–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1999.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe DL, Brown TN. Transcriptional inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) activity by a c-fos/estrogen receptor fusion protein is mediated by the proximal AP-1 site of the MMP-9 promoter and correlates with reduced tumor cell invasion. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 1999;1:368–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S, Fujii K, Fukui M. De novo aneurysm formation and aneurysm growth following therapeutic carotid occlusion for intracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;120:20–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02001464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G, Elemer G, Guelpa C, Vallotton MB, Badonnel MC, Huttner I. Morphologic and functional changes of the aortic intima during experimental hypertension. The American journal of pathology. 1979;96:399–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Hoi Y, Swartz DD, Kolega J, Siddiqui A, Meng H. Nascent aneurysm formation at the basilar terminus induced by hemodynamics. Stroke. 2008;39:2085–2090. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.509422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewaltig MT, Kojda G. Vasoprotection by nitric oxide: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Cardiovascular research. 2002;55:250–260. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HC. Twisted blood vessels: symptoms, etiology and biomechanical mechanisms. Journal of vascular research. 2012;49:185–197. doi: 10.1159/000335123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen VB, Skajaa K, Aalkjaer C, Oxlund H, Glavind EB, Petersen OB, Forman A. The effect of oophorectomy on mechanical properties of rabbit cerebral and coronary isolated small arteries. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;175:1272–1280. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrod CG, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. Deficiencies in estrogen-mediated regulation of cerebrovascular homeostasis may contribute to an increased risk of cerebral aneurysm pathogenesis and rupture in menopausal and postmenopausal women. Medical hypotheses. 2006;66:736–756. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N, Handa H, Hazama F. Experimentally induced cerebral aneurysms in rats. Surgical neurology. 1978;10:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N, Handa H, Hazama F. Experimentally induced cerebral aneurysms in rats: part II. Surgical neurology. 1979;11:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N, Handa H, Nagata I, Hazama F. Animal model of cerebral aneurysms: pathology and pathogenesis of induced cerebral aneurysms in rats. Neurological research. 1984;6:33–40. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1984.11739661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroki M, Miyashita K, Oda M. Tortuosity of the white matter medullary arterioles is related to the severity of hypertension. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2002;13:242–250. doi: 10.1159/000057850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoi Y, Gao L, Tremmel M, Paluch RA, Siddiqui AH, Meng H, Mocco J. In vivo assessment of rapid cerebrovascular morphological adaptation following acute blood flow increase. Journal of neurosurgery. 2008;109:1141–1147. doi: 10.3171/JNS.2008.109.12.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inci S, Spetzler RF. Intracranial aneurysms and arterial hypertension: a review and hypothesis. Surgical neurology. 2000;53:530–540. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00244-5. discussion 540-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamous MA, Nagahiro S, Kitazato KT, Satomi J, Satoh K. Role of estrogen deficiency in the formation and progression of cerebral aneurysms. Part I: experimental study of the effect of oophorectomy in rats. Journal of neurosurgery. 2005a;103:1046–1051. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamous MA, Nagahiro S, Kitazato KT, Tamura T, Kuwayama K, Satoh K. Role of estrogen deficiency in the formation and progression of cerebral aneurysms. Part II: experimental study of the effects of hormone replacement therapy in rats. Journal of neurosurgery. 2005b;103:1052–1057. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolega J, Gao L, Mandelbaum M, Mocco J, Siddiqui AH, Natarajan SK, Meng H. Cellular and molecular responses of the basilar terminus to hemodynamics during intracranial aneurysm initiation in a rabbit model. Journal of vascular research. 2011;48:429–442. doi: 10.1159/000324840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille BL. Arterial remodeling: relation to hemodynamics. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 1996;74:834–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux S, Tronc F, Tedgui A. Mechanisms of blood flow-induced vascular enlargement. Biorheology. 2002;39:319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum M, Kolega J, Dolan JM, Siddiqui AH, Meng H. A critical role for proinflammatory behavior of smooth muscle cells in hemodynamic initiation of intracranial aneurysm. PloS one. 2013;8:e74357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masawa N, Yoshida Y, Yamada T, Joshita T, Sato S, Mihara B. Morphometry of structural preservation of tunica media in aged and hypertensive human intracerebral arteries. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1994;25:122–127. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Metaxa E, Gao L, Liaw N, Natarajan SK, Swartz DD, Siddiqui AH, Kolega J, Mocco J. Progressive aneurysm development following hemodynamic insult. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011;114:1095–1103. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.JNS10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, Siddiqui A. High WSS or Low WSS? Complex Interactions of Hemodynamics with Intracranial Aneurysm Initiation, Growth, and Rupture: Toward a Unifying Hypothesis. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2013 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metaxa E, Tremmel M, Natarajan SK, Xiang J, Paluch RA, Mandelbaum M, Siddiqui AH, Kolega J, Mocco J, Meng H. Characterization of critical hemodynamics contributing to aneurysmal remodeling at the basilar terminus in a rabbit model. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2010;41:1774–1782. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.585992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata I, Handa H, Hashimoto N, Hazama F. Experimentally induced cerebral aneurysms in rats: Part VI. Hypertension. Surgical neurology. 1980;14:477–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy MA, Levesque MJ. SCANNING ELECTRON-MICROSCOPIC STUDY OF ARTERIAL ENDOTHELIAL CELLS USING VASCULAR CASTS. Atherosclerosis. 1977;28:463–470. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(77)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susic D. Hypertension, aging, and atherosclerosis. The endothelial interface. The Medical clinics of North America. 1997;81:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MT, Aguiar GB, Jory M, Conti ML, Veiga JC. De novo basilar tip aneurysm. Case report and literature review. Neurocirugia (Asturias, Spain) 2011;22:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(11)70020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada Y, Wada K, Shimada K, Makino H, Liang EI, Murakami S, Kudo M, Shikata F, Pena Silva RA, Kitazato KT, Hasan DM, Kanematsu Y, Nagahiro S, Hashimoto T. Estrogen protects against intracranial aneurysm rupture in ovariectomized mice. Hypertension. 2014;63:1339–1344. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timperman PE, Tomsick TA, Tew JM, Vanloveren HR. ANEURYSM FORMATION AFTER CAROTID OCCLUSION. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:329–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutino VM, Mandelbaum M, Choi H, Pope LC, Siddiqui A, Kolega J, Meng H. Aneurysmal remodeling in the circle of Willis after carotid occlusion in an experimental model. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JD, Anthony MS, Cline JM. Soy phytoestrogens: research on benefits and risks. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;44:843–852. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200112000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, 3rd, Meissner I, Brown RD, Jr., Piepgras DG, Forbes GS, Thielen K, Nichols D, O'Fallon WM, Peacock J, Jaeger L, Kassell NF, Kongable-Beckman GL, Torner JC. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]