Abstract

Background

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified a large number of genetic risk factors for schizophrenia (SCZ) featuring ion channels and calcium transporters. For some of these risk factors, independent prior investigations have examined the effects of genetic alterations on the cellular electrical excitability and calcium homeostasis. In the present proof-of-concept study, we harnessed these experimental results for modeling of computational properties on layer V cortical pyramidal cells and identified possible common alterations in behavior across SCZ-related genes.

Methods

We applied a biophysically detailed multicompartmental model to study the excitability of a layer V pyramidal cell. We reviewed the literature on functional genomics for variants of genes associated with SCZ and used changes in neuron model parameters to represent the effects of these variants.

Results

We present and apply a framework for examining the effects of subtle single nucleotide polymorphisms in ion channel and calcium transporter-encoding genes on neuron excitability. Our analysis indicates that most of the considered SCZ-related genetic variants affect the spiking behavior and intracellular calcium dynamics resulting from summation of inputs across the dendritic tree.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that alteration in the ability of a single neuron to integrate the inputs and scale its excitability may constitute a fundamental mechanistic contributor to mental disease, alongside the previously proposed deficits in synaptic communication and network behavior.

Keywords: Biophysical modeling, Functional genomics, Genome-wide association studies, Layer V pyramidal cell, Neuron excitability, Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a severe mental disorder with heritability estimates ranging from .6 to .8 (1). A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified more than a hundred genes exceeding genome-wide significance, confirming the polygenic nature of this psychiatric disorder (2). This remarkable success in gene discovery brings up the next big challenge for psychiatric genetics–translation of the genetic associations into biological insights (3). Attaining this goal is supported by the development of biophysically detailed neuron models, boosted by the recent launch of mega-scale neuroscience projects (4). These models make it possible to investigate SCZ disease mechanisms by computational means, ultimately aiming toward achieving better clinical treatments and disorder outcomes (5,6).

The 108 recently confirmed SCZ-linked loci span a wide set of protein-coding genes (2), including numerous ion channel-encoding genes. The disorder is associated with genes affecting transmembrane currents of all major ionic species, sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and calcium (Ca2+). In addition, some of the SCZ-linked genes are involved in regulation of the Ca2+ concentration in the intracellular medium (2), which is another great contributor to excitability. It is thus reasonable to hypothesize that the SCZ-linked genes should have an impact on the excitability at the single-neuron level.

We focused our study on cortical layer V pyramidal cells (L5PCs) as a principal computational element of the cerebral circuit. An L5PC extends throughout the cortical depth with the soma located in layer V and the apical dendrite branching into the apical tuft in layer I, and its long axon may project to nonlocal cortical and subcortical areas. The tuft serves as an integration hub for long-distance synaptic inputs and is often considered a biological substrate for cortical associations providing high-level context for low-level (e.g., sensory) inputs to the perisomatic compartment (7). Therefore, the ability of L5PCs to communicate the apical inputs to the soma has been proposed as one of the mechanisms that could be impaired in the mental disease (7). In agreement with this hypothesis, recent psychiatric GWASs consistently reported association of genes coding for the subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels as risk factors in SCZ and bipolar disorder (8–10).

In the present proof-of-principle study, we applied a model (11) of L5PCs to explore how genetic variants in SCZ-linked genes affect the single-cell excitability. We carried out our study by linking a documented effect of a genetic variant in an ion channel or Ca2+ transporter-encoding gene to a change in the corresponding neuron model parameter. It should, however, be noted that information does not generally exist for the effect of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants identified through GWASs on the biophysical parameters required for the computational models. We instead used information obtained from in vitro studies of more extreme genetic variations, including loss-of-function mutations. A central assumption of this approach is that the effects of SNP variants can be represented as scaled-down versions of those of the more extreme variants and that the emergence of the full psychiatric disease phenotype results from the combined effect of a large number of subtle SNP effects (12,13). A deficit in synaptic communication is likely to contribute to SCZ (2,14–16) but is outside the scope of the present work.

Methods and Materials

The L5PC Model

The multicompartmental neuron model used in this work was based on a reconstructed morphology of a layer V thick-tufted pyramidal neuron [cell #1 in (11)]. The model includes the following ionic currents: fast inactivating Na+ current, persistent Na+ current, nonspecific cation current, muscarinic K+ current, slow inactivating K+ current (IKp), fast inactivating K+ current, fast noninactivating K+ current, high-voltage activated Ca2+ current, low-voltage activated Ca2+ current, small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current (ISK), and finally, the passive leak current. See Supplement 1 for the model equations, and for the simulation codes, see ModelDB entry 169457 (http://senselab.med.yale.edu/ModelDB/showModel.cshtml?model=169457).

Genes Included in the Study

Since we did not aim to provide a comprehensive evaluation of a representative fraction of the genetic risk factors of SCZ but rather to provide a proof of principle of the computational modeling approach, we selected the genomic loci using the following approach. We based our study on a recent GWAS (2), which reported significantly associated SNPs that were scattered across hundreds of genes with a variety of cellular functions. We concentrated on those genes that encoded either ionic channels or proteins contributing to transportation of intracellular Ca2+ ions.

We used the SNP-wise p value data of Ripke et al. (2), and for each gene of interest we determined the minimum p value among those SNPs that were located in the considered gene. We performed this operation for all genes encoding either subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+, K+, or Na+ channel; subunits of a small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK), leak, or hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel; or Ca2+-transporting ATPase. The genes CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA1I, ATP2A2, and HCN1 possessed a small minimum p value each (p < 3 × 10−8)–these genes were also highlighted in the locus-oriented association analysis as performed in Ripke et al. (2). To extend our study to explore a larger set of genes, we used a more relaxed threshold (p < 3 × 10−5) for the minimum p value and obtained the following genes in addition to the previously mentioned ones: CACNA1D, CACNA1S, SCN1A, SCN7A, SCN9A, KCNN3, KCNS3, KCNB1, KCNG2, KCNH7, and ATP2B2. Of these, we omitted the genes that are not relevant for the firing behavior of an L5PC. It should be noted that we used the SNPs reported in Ripke et al. (2) only to name the above SCZ-related genes, and due to lack of functional genomics data, we could not include the actual SCZ-related SNPs in our simulation study. Instead, we searched in PubMed for functional genomic studies reporting the effects of any genetic variant of the above genes. For details, see Supplement 1.

Results

A New Framework for Bridging the Gap Between GWASs of SCZ and Computational Neuroscience

In this work, we reviewed the literature on effects of variants in SCZ-related genes on ion channel behavior and intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and interpreted the reported effects in the context of our neuron model parameters. An overview of the relevant studies is given in Table 1, while the effects of each variant on the L5PC model parameters are given in Table 2. These data gave us a direct interface for linking a change in the genomic data, such as an SNP or an alternative splicing, into a change in neuron dynamics. The reported data, however, often corresponded to variants with large phenotypic consequences that, in general, are absent in SCZ patients. To simulate subtle cellular effects caused by the common SNPs related to SCZ (17), we downscaled the variants of Table 2 by bringing the changed parameters closer to the control neuron values when the reported change caused too large an effect in the neuron firing behavior. Our approach is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1. Table of the Genetic Variants Used in This Study.

| Gene | References | Type of Variant | Cell Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| CACNA1C | (43) | L429T, L434T, S435T, S435A, S435P | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | (43) | L779T, I781T, I781P | TSA201 |

| CACNB2 | (44) | T11I-mutant | TSA201 |

| CACNB2 | (45) | A1B2 vs A1 alone | HEK293 |

| CACNB2 | (46) | N1 vs N3 vs N4 vs N5 | HEK293 |

| CACNA1D | (47,48) | 42A splices transfected | TSA201/HEK293 |

| CACNA1D | (47,48) | 43S splices transfected | TSA201/HEK293 |

| CACNA1D | (42,49) | Homozygous knockout | AV node cells / chromaffin cells |

| CACNA1I | (41) | Alternative splicing of exons 9 and 33 | HEK293 |

| ATP2A2 | (50) | Heterozygous null mutation | Myocytes |

| ATP2B2 | (51) | Heterozygous knockout | Purkinje cells |

| ATP2B2 | (52) | Homozygous knockout | Purkinje cells |

| ATP2B2 | (53) | G283S-, G293S-mutant | CHO cells |

| SCN1A | (54) | FHM mutation Q1489K | Cultured neocortical cell |

| SCN1A | (55) | FHM mutation L1649Q | TSA201 |

| SCN9A | (56) | I228M NaV1.7 variant | HEK293 |

| SCN9A | (57) | A1632E NaV1.7 mutation | HEK293 |

| SCN9A | (58) | L858F NaV1.7 mutation | HEK293 |

| SCN9A | (59) | F1449V NaV1.7 mutation | HEK293 |

| KCNS3 | (60) | hKv2.1-(G4S)3-hKv9 fusion inserted | HEK293 |

| KCNB1 | (61) | T203K, T203D, S347K, S347D, T203W, S347W | Ltk– |

| KCNN3 | (62) | hSK3_ex4 isoform | tsA |

| HCN1 | (63) | D135W, D135H, D135N mutants | HEK293 |

For more details, see Table 2.

AV, atrioventricular; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; FHM, familial hemiplegic migraine; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293.

Table 2. List of Variants and Their Threshold Effect Coefficients c.

| Gene | Variant Effect on Model Parameters | Threshold Effect |

|---|---|---|

| CACNA1C | Voffm*,CaHVA: −25.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −27.0 mV | c = .094 |

| CACNA1C | Voffm*,CaHVA: −37.3 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −30.0 mV | c = .060a |

| CACNB2 | Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.2 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .69 | c = .582 |

| CACNB2 | τh*,CaHVA: × 1.7 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| CACNB2 | Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .310 |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .154 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .205 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .675b | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .814 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .057 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .517 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × .6 | c = .078 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .275 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .188 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .190 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × .6; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = 1.687 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .707 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .061 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .457a,c | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +4.9 mV; Voffh*,CaHVA: +5.1 mV; τm*,CaHVA: × 1.68; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.66 | c = .084 | |

| CACNA1D | Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.9 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .73; Voffh*,CaHVA: −3.0 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .81; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.25 | c = .118 |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.9 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .73; Voffh*,CaHVA: +3.5 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .81; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.25 | c = .106 | |

| CACNA1D | Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .8; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.3 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .114 |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +3.4 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .8; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.3 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = 1.962 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.12; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.3 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .131 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +3.4 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.12; Voffh*,CaHVA: −5.3 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .601 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .8; Voffh*,CaHVA: +1.2 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .100 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +3.4 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .8; Voffh*,CaHVA: +1.2 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .645 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: −10.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.12; Voffh*,CaHVA: +1.2 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = .116 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +3.4 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.12; Voffh*,CaHVA: +1.2 mV; Vsloh*,CaHVA: × .66; τh*,CaHVA: × .72 | c = 1.117 | |

| CACNA1D | Voffm*,CaHVA: +6.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .75; τh*,CaHVA: × .5 | c = .104 |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +6.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.19; τh*,CaHVA: × .5 | c = .068 | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +6.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × .75; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.12 | c = .115b | |

| Voffm*,CaHVA: +6.6 mV; Vslom*,CaHVA: × 1.19; τh*,CaHVA: × 1.12 | c = .072 | |

| CACNA1I | Voffma,CaLVA: +1.3 mV; Voffha,CaLVA: +1.6 mV; τm*,CaLVA: × .87; τh*,CaLVA: × .8 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| Voffma,CaLVA: +1.3 mV; Voffha,CaLVA: +1.6 mV; τm*,CaLVA: × 1.45; τh*,CaLVA: × .8 | c ≥ 2.000a,b | |

| ATP2A2 | γCaDynamics: × .6 | c = .093b |

| ATP2B2 | τdecay,CaDynamics: × 1.97 | c = .218 |

| ATP2B2 | τdecay,CaDynamics: × 1.5; cmin,CaDynamics: × 1.4 | c = .215a |

| ATP2B2 | τdecay,CaDynamics: × 4.45 | c = .099 |

| SCN1A | Voffm,Nat: −.3 mV; Voffh,Nat: +5 mV; Vslom,Nat: × 1.15; Vsloh,Nat: × 1.23 | c = .056a |

| SCN1A | Voffm,Nat: +2.8 mV; Voffh,Nat: +9.6 mV; Vslom,Nat: × .984; Vsloh,Nat: × 1.042 | c = .069 |

| SCN9A | Voffh*,Nap: +6.8 mV | c ≥ 2.000 |

| SCN9A | Voffh*,Nap: +3.5 mV; Vsloh,Nap: × .55; Voffm,Nat: −7.1 mV; Voffh,Nat: +17.0 mV; Vsloh,Nat: × .69 | c = .026 |

| SCN9A | Voffm,Nat: −9.1 mV; Voffh,Nat: +3.1 mV | c = .043 |

| SCN9A | Voffm,Nat: 27.6 mV; Voffh,Nat: +4.3 mV | c = .043 |

| KCNS3 | τm*,Kp: × 2.0; τh*,Kp: × 2.5; Vsloh,Kp: × .5 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: +5 mV; Voffh,Kp: 13 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 1.11; Vsloh,Kp: × .86; τm*,Kp: × .5; τh*,Kp: × .53 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: +1 mV; Voffh,Kp: −6 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 1.22; Vsloh,Kp: × 1.0; τm*,Kp: × .89; τh*,Kp: × 1.13 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: +6 mV; Voffh,Kp: −8 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 1.33; Vsloh,Kp: × 1.0; τm*,Kp: × .5; τh*,Kp: × .87 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: −28 mV; Voffh,Kp: −27 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 1.11; Vsloh,Kp: × .71; τm*,Kp: × 1.13; τh*,Kp: × 2.27 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: +14 mV; Voffh,Kp: −21 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 2.0; Vsloh,Kp: × 1.0; τm*,Kp: × .39; τh*,Kp: × 1.2 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNB1 | Voffm,Kp: −13 mV; Voffh,Kp: −13 mV; Vslom,Kp: × 1.33; Vsloh,Kp: × .71; τm*,Kp: × .95; τh*,Kp: × 5.13 | c ≥ 2.000 |

| KCNN3 | Coff,SK: × .86; Cslo,SK: × 1.24 | c = 1.715a,b |

| HCN1 | Voffm*,Ih: −26.5 mV; Vslom*,Ih: × .64 | c = .296 |

The variants are ordered as in Table 1, but the variants where several combinations of parameter range end points were considered are listed as separate variants (Supplement 1).

CaHVA, high-voltage activated Ca2+; CaLVA, low-voltage activated Ca2+; Ih, nonspecific cation current; Kp, slow inactivating K+; Nap, persistent Na+; Nat, fast inactivating Na+; SK, small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+.

The variants were used in Figure S3 in Supplement 1.

The variant was used in Figure 1.

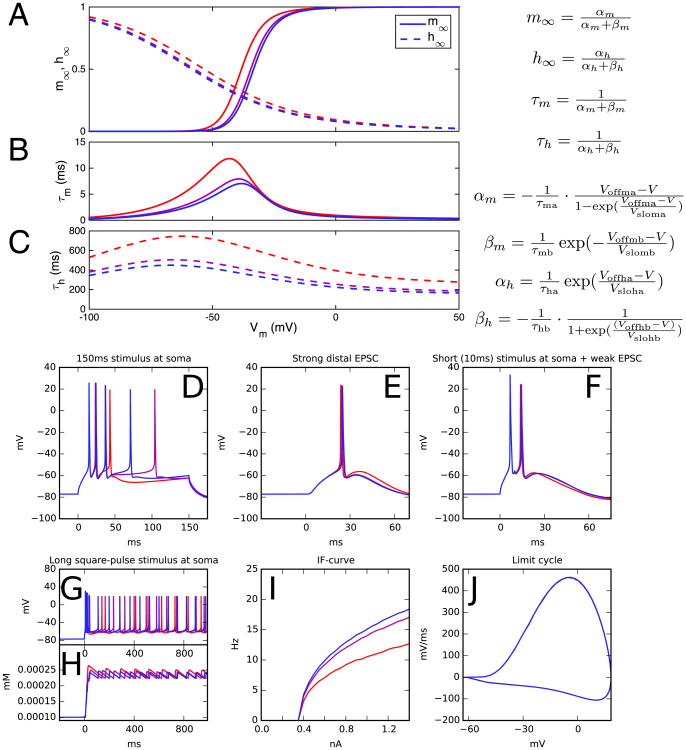

Figure 1.

An example of downscaling with a variant (46) of the gene CACNB2. Link et al. (46) transfected different variants of CACNB2 DNA into HEK293 cells together with CaV1.2 subunit DNA and measured the activation and inactivation curves of the calcium currents through the cell membrane. The cells transfected with different variants showed different values of midpoints and time constants for channel activation and inactivation: the midpoints of activation and inactivation varied by ±4.9 and ±5.1 mV among the variants, respectively, while the time constants of activation and inactivation varied from −40% to +68% and −40% to +66%, respectively. Here, we illustrate a variant representing one possible combination of the end points of these ranges. (A) The voltage dependence of steady-state activation (m∞) and inactivation (h∞) according to the neuron model (11). Red curves represent the unscaled variant: activation parameters Voffma and Voffmb are changed by Δ1 = −4.9 mV, inactivation parameters Voffha and Voffhb are changed by Δ2 = 5.1 mV, activation time constants τma and τmb are increased by 68% (η3 = 1.68), and inactivation time constants τha and τhb are increased by +66% (η4 = 1.66). Purple curves show the downscaled ε = ½ variant (see below), and blue curves show the control neuron activation properties. (B, C) The voltage dependence of time constants for activation (B) and inactivation (C). (D-J) Illustration of the scaling conditions. The downscaling is based on five conditions (Supplement 1), none of which should be violated in the downscaled variant. In panels (D-F) (conditionswith different scalings I-III), the variant neuron should respond with the same number of spikes as the control neuron (blue). In panel (I), the integrated difference between the variant and control f-I curves (firing frequency as a function of direct current amplitude) should not exceed 10% of the integral of the control curve (condition IV). In panel (J), the difference between the limit cycles should not exceed a set limit (condition V). It can be observed that the unscaled variant (red) violates the conditions I and IV. To scale down the variant, each applied parameter change is brought to a fraction c < 1, all in proportion, until the threshold of violating/nonviolating variant is found. In this example, the threshold variant corresponds to parameter changes c × Δ1, c × Δ2, η3c, and η4c, where c = .4574. Any nonnegative value below the threshold value c yields a downscaled variant that obeys conditions I-V. The purple curves represent the variant corresponding to parameter changes cε × Δ1, cε × Δ2, η3cε, and η4cε, where c = .4574 and ε = ½. The blue curves show the control neuron firing behavior. (D) Somatic membrane potential as a response to a 150-ms somatic square-pulse stimulus (.696 nA). (E) Somatic response to a distal apical synaptic conductance with maximum .0612 μS. (F) Somatic response to a combination of somatic square-pulse current (10 ms × 1.137 nA) and a distal apical synaptic conductance (maximum .100 μS). (G) Somatic membrane potential as a response to a long somatic square-pulse stimulus current (1.0 nA). (H) Somatic calcium concentration as a response to the stimulus used in (G). (I) Spiking frequency as a function of amplitude of the somatic direct current. (J) The membrane potential limit cycle corresponding to the late phase of (G). The x-axis represents the somatic membrane potential and y-axis its time derivative. EPSC, excitatory postsynaptic current.

The variants in Table 1 were 23 in total, although some of them represented a range of effects of different variants (Table S1 in Supplement 1). The entries corresponded to variants of genes encoding for Ca2+ channel subunits (CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA1D, CACNA1I), intracellular Ca2+ pumps (ATP2A2, ATP2B2), Na+ channel subunits (SCN1A, SCN9A), K+ channel subunits (KCNS3, KCNB1, KCNN3), and a nonspecific ion channel subunit (HCN1). In the following, we present simulation results for the L5PC model equipped with some of these downscaled variants (we refer to these model neurons as variant neurons or simply as variants). As we did not know the quality of the effects of the actual SCZ-related polymorphisms, we performed the simulations for a range of differently scaled variants, including negative scalings (i.e., opposite effects with regard to the effects reported in Table 2). We concentrated our study on a representative sample of six variants, highlighted in Table 2. These variants represented six genes with different roles in L5PC electrogenesis and a wide range of observed effects (Table S2 in Supplement 1).

Variants Show Altered Intracellular (Ca2+) Responses to Short Stimuli

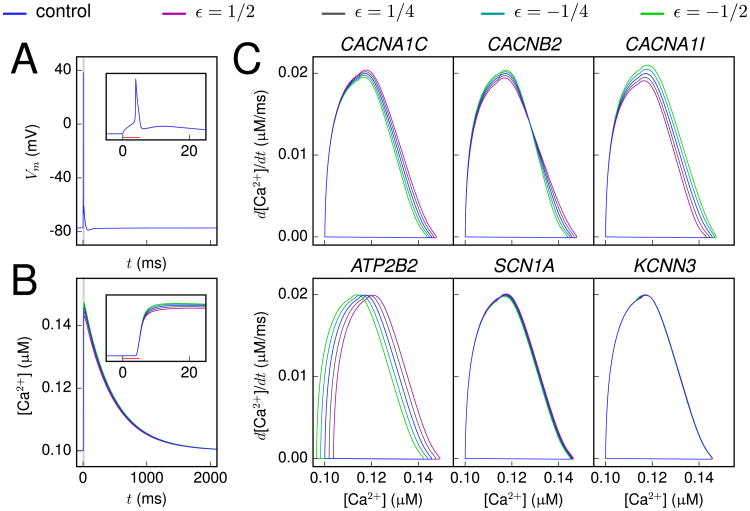

To characterize the implications of SCZ-related genes on the neuron excitability, we started by analyzing the effects of the downscaled versions of genetic variants in Table 2 on the neuron response to a short somatic suprathreshold square-pulse stimulus. Figure 2A and B shows the time course of the membrane potential and the intracellular Ca2+concentration ([Ca2+]) for one variant, whereas Figure 2C shows the [Ca2+] response in the phase plane for several different variants. The most typical effect of a variant was a deviation in the peak [Ca2+], but differences could also be observed in the rising phase of the [Ca2+], as shown in the phase plane representation in Figure 2C.

Figure 2.

Variants show altered [Ca2+] response to a short, somatic stimulus. (A, B) The membrane potential (A) and calcium (Ca2+) concentration (B) time courses, recorded at soma, as a response to a somatic 5-ms, 1.626 nA square-pulse stimulus. The blue curve shows the control neuron behavior, while the other curves show the behavior of a CAC-NA1I variant (41) with different scalings (magenta: ε = ½, dark gray: ε = ¼, cyan: ε = −¼, green: ε = −½). Inset: Zoomed-in view around the time of the spike. No notable differences between the variants and the control can be observed in the membrane potential time course. (C) The [Ca2+] response plotted in the phase plane for different variants. The behavior of variants of CACNA1C (43), CACNB2 (46), CACNA1I (41), ATP2B2 (52), SCN1A (54), and KCNN3 (62) genes are shown with similar scaling as in (A) and (B).

The results in Figure 2 show that the [Ca2+] response served as a more sensitive indicator of genetic effects than the membrane potential. In CACNA1C and CACNB2 variants, which affect the high-voltage-activated Ca2+ current, and in the CACNA1I variant, which affects the low-voltage-activated Ca2+ current, the observed effects on the [Ca2+] response were due to changed Ca2+ channel kinetics. Similarly, in the ATP2B2 variant, which affects the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) activity, the observed effect was caused by altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. By contrast, the small yet observable differences between control and SCN1A variant [Ca2+] phase planes were due to alterations in subthreshold membrane potential fluctuations, which caused variation in the activation of Ca2+ channels.

Steady-State Firing Is Influenced by the Variants

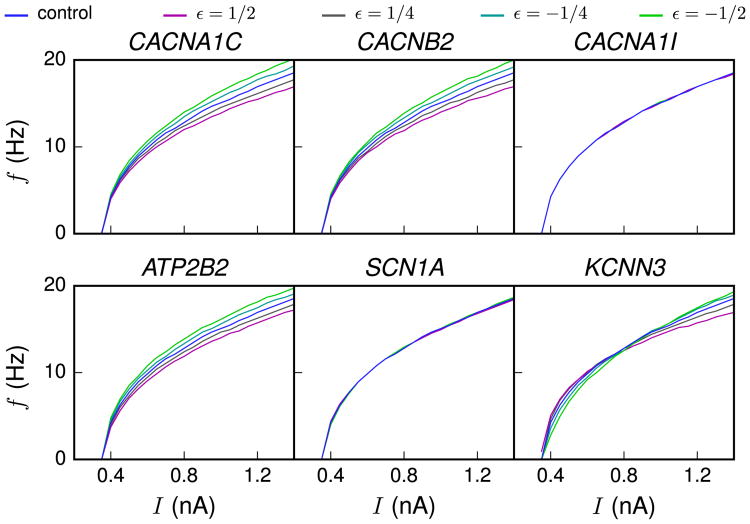

Next, we investigated the steady-state behavior of the neuron when a direct current was applied to the soma. As shown in Figure 3, the f-I curves (firing frequency as a function of direct current amplitude) of many SCZ-associated variants were notably different from those obtained with the control neuron.

Figure 3.

The variant neurons show modulated gain. f-I curves (firing frequency as a function of direct current amplitude) are shown for different scalings of different variants (magenta: ε = ½, dark gray: ε = ¼, cyan: ε = −¼, green: ε = −½). Differences in gain are visible for CACNA1C, CACNB2, ATP2B2, and KCNN3 variants.

The deviations in the f-I curves in many of the variants can be explained by changes in the Ca2+-activated SK current. These changes were caused either by direct alteration of the activation kinetics of SK channels (as in the KCNN3 variant) or indirectly through the changes in the intracellular [Ca2+] response associated with other variants (CACNA1C, CACNB2, and ATP2B2). As an example, the Ca2+ influx during an action potential was larger in the CACNA1C variant neuron compared with the control neuron (compare curves in blue and magenta in Figure 2C), and this led to an increase in the SK current activation, relative to that in the control neuron. The increased ISK, in turn, delayed the induction of the next spike and hence resulted in a loss of gain (flattening) in the f-I curve (Figure 3). This finding is in line with previous modeling studies that also have highlighted the role of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in modulating f-I curves (18,19).

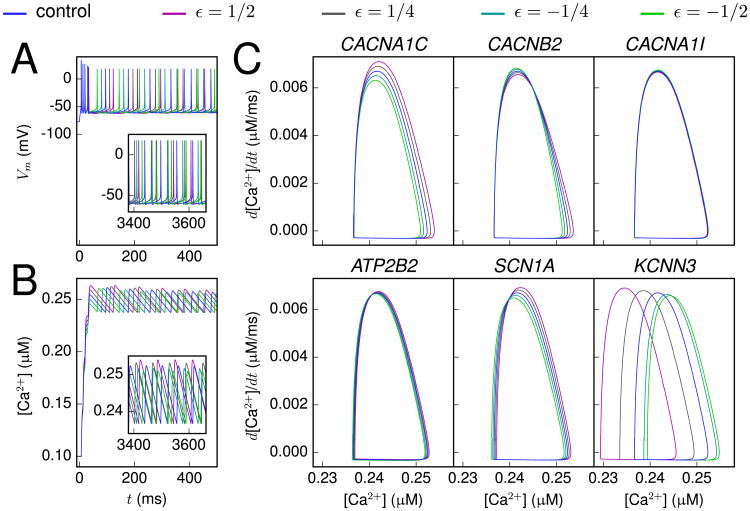

We also studied the steady-state firing behavior by analyzing the limit cycle, i.e., the phase plane representation of the variable of interest after a large number of initial cycles. As the [Ca2+] response served as the most sensitive biomarker, we used the [Ca2+] limit cycle for this analysis. Figure 4 shows, for some of the gene variants, the [Ca2+] limit cycle as a response to a long, square-pulse stimulus.

Figure 4.

Differences in [Ca2+] limit cycles of the variants. (A, B) The membrane potential (A) and calcium (Ca2+) concentration (B) time courses at soma as a response to a direct current with an amplitude of 1.2 nA. The different colors represent different scalings of a CACNA1C variant (43) (scaling as in Figure 2). Inset: The time course shown 3.4 seconds since the beginning of the stimulus. (C) The intracellular [Ca2+] phase plane during steady firing caused by a direct current applied to the soma. The variants and their scalings were chosen as in Figure 2C.

The different variants had different ways of impacting the shape of the [Ca2+] limit cycle. An especially common trait was a shift or compression in the horizontal direction, representing a small increase or decrease of intracellular [Ca2+] during steady firing. Figure S1 in Supplement 1 shows the range of [Ca2+] values observed during the constant current injection for all variants used in this study. Interestingly, almost all variants gave deviations from the [Ca2+] range observed in the control neuron.

The only genes that did not show notable variance for the range of [Ca2+] during steady-state firing were CACNA1I, KCNS3, and KCNB1. Despite this, CACNA1I did have a clear effect on the [Ca2+] phase plane in the single-pulse response (Figure 2C). Conversely, the KCNS3 and KCNB1 variants were not found to influence any of the considered aspects of neuron behavior (Figures S1 and S2 in Supplement 1). In these variants, the activation and inactivation of IKp have been modified. Our findings reflect the overall minor role that the current IKp plays in shaping the response properties of the L5PC model neuron: it is only present in the soma and with relatively small maximal conductance (11). The minor contribution of this current to the model neuron behavior may be in contradiction with experimental evidence, which states that this current constitutes a major proportion of the total outward K+ currents (20).

Variants Have an Effect on Integration of Somatic and Apical Inputs

A question that arises from the observation of the above trends is whether, and to what extent, the small deviations from control neuron behavior affect the information processing capabilities of the neuron. In Hay et al. (11), it was shown that the L5PC model can be used to describe the Ca2+ spike generation as a response to a combination of stimuli at the apical dendrite and at the soma. Moreover, they showed a good qualitative match with experimental data and model predictions for the neuron responses during an up or down state. In this work, we followed their definition for the down state as the resting state of the neuron and the up state as a state where a subthreshold current is applied to the proximal apical dendrite (11). We also adopted their protocol of combining an apical stimulus and somatic stimulus and studying the effect of order and interstimulus interval (ISI) between the two [see Figure 8 in Hay et al. (11)]. This gave us a temporal profile showing a range of ISI for which a large Ca2+ spike is produced. We then estimated the effect of our genetic variants on this temporal profile.

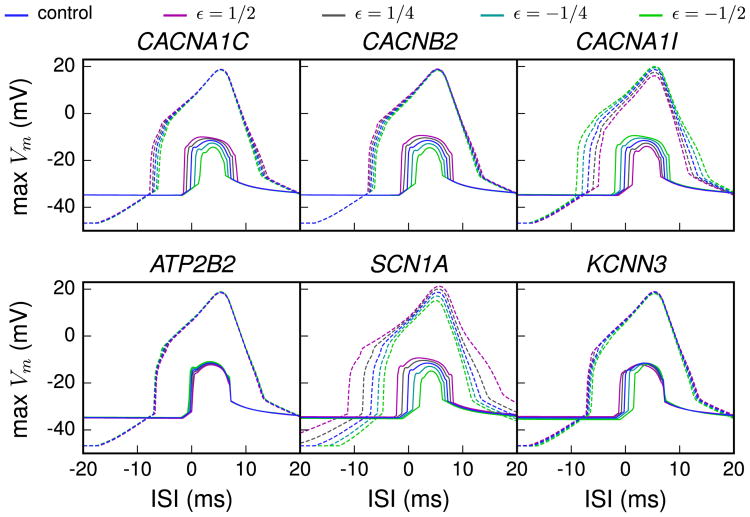

Figure 5 shows the temporal profiles for the six representative variants. Effects of the different variants on the neuron response were visible both during the down and during the up states. Particularly large effects were observed in CACNA1I and SCN1A variants, which code for the low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and transient Na+ channels that contribute to the sharp rise of voltage during an action potential. These channel types are expressed both in the soma and in the apical dendrite. Although all downscaled variants shared the basic form of the response curves, the shape was clearly altered in some variants. As shown in Hay et al. (11), the up state temporal profile of the control neuron showed elevated apical responses when the apical stimulus was applied shortly after the somatic stimulus but not when the apical stimulus was applied first. This order-specific response was changed in some of the variants (e.g., SCN1A variant) so that they also produced large Ca2+ spikes when the apical stimulus was applied shortly before the somatic stimulus and could hence alter the order sensitivity of the coincidence detection.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of variant neurons to interstimulus interval (ISI) between somatic and distal apical stimuli during up and down states. The magnitude of the calcium spikes was assessed by measuring the simulated membrane potential near the bifurcation point of the apical dendrite, i.e., at a distance of 620 μm from the soma. The dashed lines show the temporal maximum of the model response membrane potential during a down state and the solid lines during an up state. The x-axis represents the ISI between the somatic and apical stimuli, positive values denoting cases where the apical stimulus was applied after the somatic stimulus. The variants shown are the same as in Figure 2. In the up state paradigm, the neuron was first given a depolarizing square-pulse current of .42 nA × 200 ms at the proximal apical dendrite, 200 μm from the soma. In the middle of this period, a somatic square-pulse current of .5 nA × 5 ms was applied, and after a time defined as the ISI, an alpha-shaped current injection with rise time .5 ms, decay time 5 ms, and maximal amplitude of .5 nA was applied. The down state paradigm was otherwise equal, but the long depolarizing current was absent, and to compensate for this, the short somatic square-pulse current had amplitude of 1.8 nA.

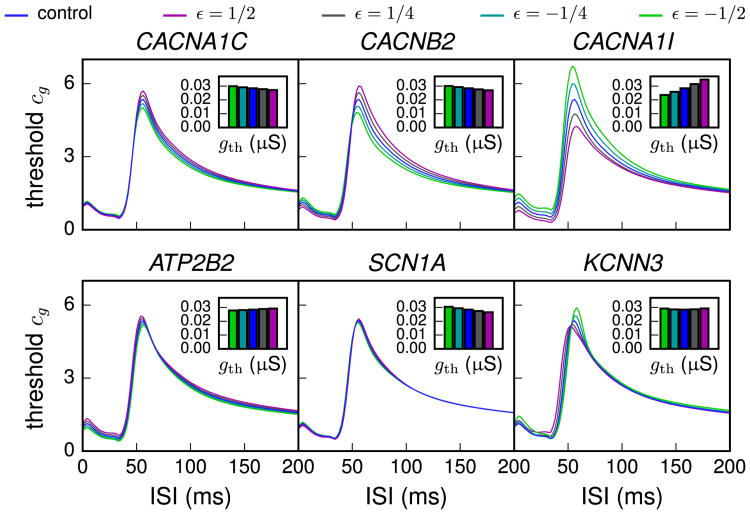

Variants Show Differences in Inhibition of a Second Apical Stimulus

The alteration of information processing by the variants can also be seen in the sensitivity to successive synaptic inputs at the same locations. To explore this, we gave two successive stimuli to the apical dendrite and varied the interval (ISI) between them. The first stimulus activated long-time scale inhibitory currents, especially ISK and muscarinic K+ current, and within some following time window, these currents could inhibit the generation of a subsequent spike. This could be interpreted as a form of single-cell prepulse inhibition: if the initial input caused the neuron to spike, the next input could fail to do so, even at times when the second stimulus was of larger amplitude.

Figure 6 shows how the threshold synaptic conductance needed for inducing a second spike, relative to the one needed for the first spike, depends on the ISI. Interestingly, the threshold conductance curve was affected by many of the variants, especially by the variants of Ca2+ channel genes. Although the shown effect was partly attributed to the differences in the spiking thresholds between the variants, differences between the variants could still be observed when absolute spiking threshold values for inducing a second spike were considered (data not shown). These findings raise the possibility that the disturbed prepulse inhibition observed in many SCZ patients might be an effect of altered ionic channel properties at the single-neuron level and not only of the modified elements in synaptic circuitry as previously thought (21,22) [cf. (23)].

Figure 6.

Threshold conductance factor for inducing a second spike as a function of interstimulus interval (ISI). The neuron was first made to spike by applying 3000 simultaneously activated synaptic conductances that were uniformly distributed along the apical dendrite at a distance (300 μm, 1300 μm) from the soma. All synaptic conductances were alpha-shaped with τ = 5 ms and maximal conductance 1.1 gth, where gth was the threshold conductance value for inducing a spike in resting state. These values were variant-specific (and scaling-specific), and they are plotted in the inset of each panel. After the specified ISI, the synapses were activated again. The y-axis shows the factor cg, chosen such that cg × gth was the threshold conductance of the second stimulus for generating an extra spike. Curves above the control curve (blue) represent strengthened prepulse inhibition, while curves below it represent weakened prepulse inhibition. The effect of the KCNN3 variant (ε = ½, magenta) was bilateral: for ISI ≲ 50 ms, the effect was strengthening, whereas for ISI ≳ 50 ms, the effect was weakening.

Discussion

We presented a framework for studying the effects of genetic variants in genes related to SCZ on layer V pyramidal cell excitability. Our results indicate that most of the studied variants predicted an observable change in the neuron behavior (Figures 2–6). Taken together, these data provide support for using neuronal modeling to study the functional implications of SCZ-related genes on neuronal excitability. Although the analyses presented in this article are specific to L5PCs and SCZ-related genes, our framework may be directly applicable to other cell types and other polygenic diseases, such as bipolar disorder and autism, given an identification of risk genes related to neuronal excitability. Furthermore, our approach can be directly extended to biophysically detailed models of neuronal networks, e.g., Hay and Segev (24).

The results shown in the present article are based on a multicompartmental neuron model (11) employing a certain set of ionic channels. Alternative models with comparable complexity have recently been published. The authors of Bahl et al. (25) present and apply a method for fitting the L5PC model to a simplified neuron morphology. In another recent work by Almog and Korngreen (26), the L5PC model was fit to each stained morphology and the corresponding recordings separately. To rule out our conclusions being an artefact of a certain specific morphology, we carried out our analyses on another neuron model fit [cell #1 equipped with channel conductance values from the first column of Table S1 in (11)] and an alternative neuron morphology [cell #2 of (11)]. The trend of the variant effects remained the same in these simulations (Figures S4 and S5 in Supplement 1). More comprehensive analysis could be carried out by using the above-mentioned alternative models or by employing a wider set of neuron morphologies (27), but this is left for future work.

Discovering the disease mechanisms of disorders with polygenic architecture, such as SCZ, requires considering the interplay between many different biological processes and entities. The computational framework presented here allows one to identify physiological mechanisms and biomarkers common across multiple risk-related genes. Although there are many more SCZ-related genes (2) than those listed in Table 1, the identified variants capture multiple types of changes in neuron excitability (Figures 2–6). This allows studying the effects of combinations of different genetic variants in a straightforward manner, as suggested in Figure S3 in Supplement 1, although one should be careful in the interpretation of the results, as certain variants could have nonadditive effects. The gene hits not considered in the present work contribute to, e.g., expression level and function of ionotropic and G-protein coupled receptors, as well as phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of diverse proteins. It should be noted that several of the identified SCZ-related genes, such as PTN, PAK6, and SNAP91, may also affect neuron morphology (28–31). Our framework could be extended to include some of these effects, but studying the contribution of many signaling genes is out of the scope of the used neuron model.

Linking cellular mechanisms to SCZ can be extremely difficult owing to the high cognitive level on which the disease symptoms usually emerge. There is, however, one important exception, namely, altered prepulse inhibition, which is found in approximately 40% to 50% of SCZ patients (32). In the present study, we showed that the considered genetic variants may have had different tendencies to suppress a second synaptic stimulus, owing only to the differences in the (non-synaptic) ion channel gating or Ca2+ dynamics (Figure 6). This could be an important contributor to understanding the phenomenon of prepulse inhibition, although deficiencies in synaptic connections are most likely to play a role as well (21). Moreover, altered integration of local and distal inputs in the manner of Figure 5 could possibly underlie incomplete or excessive activation of pyramidal cells in certain brain areas linked to auditory hallucinations [(7); see also discussion of the role of spontaneous activity in primary auditory cortex in triggering verbal hallucinations in (33)]. Experimental testing of the shown model predictions for integration of inputs on a single-cell level is possible as well. Even without genetic manipulations, the downscaled variants of the ion channels could be imitated in vitro by partial pharmacologic blocks that are configured to cause changes in currents comparable with those in our variants. However, in such a case, the fine details on, e.g., current activation time constants would be dismissed.

The genetic variation of ion channels will affect not only the membrane potentials of the neurons but also the transmembrane currents generating the local field potential recorded inside the cortex and the electrocorticography signals recorded at the cortical surface (34,35). Further, the same transmembrane currents also determine the neuronal current dipole moments measured in electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography (36,37). Thus, a natural extension of the present work is to investigate the effects of the genetic variation of the single-neuron current dipole moments (38) and the corresponding single-neuron contribution to the electroencephalography signals. This is left for future work.

A severe limitation of our approach is the lack of data on how different specific SCZ-related genetic polymorphisms affect the ion channel function and Ca2+ dynamics. In this article, we used literature data on extreme variants (e.g., loss-of-function of function mutations) of the identified SCZ-related risk genes, from a range of cell types, including nonneural tissues. Ideally, one would want to use physiological measures for the relevant genetic variants in the actual cell types (i.e., L5PCs) in cortical circuits, but such data do not currently exist. On the other hand, the diversity of data in the literature that we used and the possible discrepancies in the experimental procedures therein could also reflect in the results shown in this study, although our downscaling procedure constrained such errors from above. Novel methods employing automated cell patching (39) to test the effects of subtle SCZ-related SNPs could provide the solution to both above limitations of our study.

The validity of the downscaling, which for the aforementioned reasons is a central procedure in our framework, is built upon two assumptions: 1) the SCZ-related gene variants do affect neuronal excitability on a single-neuron level, and 2) their effects on ion channel or calcium pump kinetics are smaller than those of certain already documented mutations with extreme phenotypic consequences, such as deafness, hemiplegic migraine, or other pain disorders. The first assumption can be argued for by the multitude of ion channel-encoding genes that have been shown to be related to SCZ risk and the second assumption by the lack of severe body malfunctioning (such as the abovementioned ones) in SCZ patients, but rigorous proofs for both assumptions are yet to be shown. A challenge for future studies is also to decipher how the ion channel densities are affected by the variants in various cell types, an issue that might be important in modeling the effects of SCZ-associated polymorphisms.

Our framework is an early attempt toward understanding the disease mechanisms of polygenic psychiatric disorders by computational means. It binds together genetic and single-neuron levels of abstraction in the big picture of modeling psychiatric illnesses, as recently sketched in Wang and Krystal (5) and Corlett and Fletcher (40). While earlier computational studies considered only effects of single variants on neuron firing behavior (41,42), our framework allows the screening of multiple types of variants and their implications on the neuron excitability. It may serve as a proof of principle for a novel biophysical psychiatry approach, enabling the integration of information from previously disparate fields of study including GWASs, functional genomics, and biophysical computational modeling using models of moderate complexity. We consider the chosen level of complexity a suitable trade-off for this purpose: while more approximate models, such as integrate-and-fire models, could not distinguish between the effects of different genetic variants in an acceptable precision, more detailed models including, e.g., dynamics of protein translation and phosphorylation are likely to be very computation-intensive. The challenge for future work is to extend the study to both larger and finer spatial and temporal scales.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Norwegian Metacenter for Computational Science (NOTUR) resources were used for heavy simulations. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. 5 R01 EB000790-10, EC-FP7 Grant No. 604102 (“Human Brain Project”), Research Council of Norway (Grant Nos. 216699, 213837, and 223273), South East Norway Health Authority (Grant No. 2013-123), and KG Jebsen Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2015.09.002.

References

- 1.Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;10:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia- associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Os J, van, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grillner S. Megascience efforts and the brain. Neuron. 2014;82:1209–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang XJ, Krystal JH. Computational psychiatry. Neuron. 2014;84:638–654. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen MJ. New approaches to psychiatric diagnostic classification. Neuron. 2014;84:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkum M. A cellular mechanism for cortical associations: An organizing principle for the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet. 2011;43:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: A genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay E, Hill S, Schürmann F, Markram H, Segev I. Models of neocortical layer 5b pyramidal cells capturing a wide range of dendritic and perisomatic active properties. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman II, Shields J. A polygenic theory of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58:199–205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Schizophrenia Consortium. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D, et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fromer M, Pocklington AJ, Kavanagh DH, Williams HJ, Dwyer S, Gormley P, et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature. 2014;506:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen Z, Nguyen HN, Guo Z, Lalli MA, Wang X, Su Y, et al. Synaptic dysregulation in a human iPS cell model of mental disorders. Nature. 2014;515:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature13716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, DeCandia TR, Ripke S, Yang J, et al. Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study Consortium (PGC-SCZ), International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) Estimating the proportion of variation in susceptibility to schizophrenia captured by common SNPs. Nat Genet. 2012;44:247–250. doi: 10.1038/ng.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel J, Schultens HA, Schild D. Small conductance potassium channels cause an activity-dependent spike frequency adaptation and make the transfer function of neurons logarithmic. Biophys J. 1999;76:1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halnes G, Augustinaite S, Heggelund P, Einevoll GT, Migliore M. A multi-compartment model for interneurons in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan D, Tkatch T, Surmeier D, Armstrong W, Foehring R. Kv2 subunits underlie slowly inactivating potassium current in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2007;581:941–960. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swerdlow N, Geyer M. Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in rats after lesions of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:104–117. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medan V, Preuss T. Dopaminergic-induced changes in Mauthner cell excitability disrupt prepulse inhibition in the startle circuit of goldfish. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:3195–3204. doi: 10.1152/jn.00644.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch M. Clinical relevance of animal models of schizophrenia. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;62:113–120. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-7020-5307-8.00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hay E, Segev I. Dendritic excitability and gain control in recurrent cortical microcircuits. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:3561–3571. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahl A, Stemmler MB, Herz AV, Roth A. Automated optimization of a reduced layer 5 pyramidal cell model based on experimental data. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;210:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almog M, Korngreen A. A quantitative description of dendritic conductances and its application to dendritic excitation in layer 5 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:182–196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2896-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hay E, Schürmann F, Markram H, Segev I. Preserving axosomatic spiking features despite diverse dendritic morphology. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109:2972–2981. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deuel TF, Zhang N, Yeh HJ, Silos-Santiago I, Wang ZY. Pleiotrophin: A cytokine with diverse functions and a novel signaling pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:162–171. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nekrasova T, Jobes ML, Ting JH, Wagner GC, Minden A. Targeted disruption of the Pak5 and Pak6 genes in mice leads to deficits in learning and locomotion. Dev Biol. 2008;322:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ang LH, Kim J, Stepensky V, Hing H. Dock and Pak regulate olfactory axon pathfinding in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:1307–1316. doi: 10.1242/dev.00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickman DK, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Altered synaptic development and active zone spacing in endocytosis mutants. Curr Biol. 2006;16:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turetsky BI, Calkins ME, Light GA, Olincy A, Radant AD, Swerdlow NR. Neurophysiological endophenotypes of schizophrenia: The viability of selected candidate measures. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:69–94. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kompus K, Falkenberg LE, Bless JJ, Johnsen E, Kroken RA, Kråkvik B, et al. The role of the primary auditory cortex in the neural mechanism of auditory verbal hallucinations. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:144. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents–EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einevoll GT, Kayser C, Logothetis NK, Panzeri S. Modelling and analysis of local field potentials for studying the function of cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:770–785. doi: 10.1038/nrn3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunez PL, Srinivasan R. Electric Fields of the Brain: The Neurophysics of EEG. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hämäläinen M, Hari R, Ilmoniemi RJ, Knuutila J, Lounasmaa OV. Magnetoencephalography theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. Rev Mod Phys. 1993;65:413–497. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindén H, Pettersen KH, Einevoll GT. Intrinsic dendritic filtering gives low-pass power spectra of local field potentials. J Comput Neurosci. 2010;29:423–444. doi: 10.1007/s10827-010-0245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranjan R, Logette E, Petitprez S, Marani M, Mirjia H, Muller EB, et al. Automated biophysical characterization of the complete rat Kv-ion channel family. Presented at the Society for Neuroscience Meeting; November 15–19; Washington, DC. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corlett PR, Fletcher PC. Computational psychiatry: A Rosetta Stone linking the brain to mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:399–402. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murbartián J, Arias JM, Perez-Reyes E. Functional impact of alternative splicing of human T-type Cav3.3 calcium channels. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3399–3407. doi: 10.1152/jn.00498.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q, Timofeyev V, Qiu H, Lu L, Li N, Singapuri A, et al. Expression and roles of Cav1.3 (α1D) L-type Ca2+ channel in atrioventricular node automaticity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudrnac M, Beyl S, Hohaus A, Stary A, Peterbauer T, Timin E, Hering S. Coupled and independent contributions of residues in IS6 and IIS6 to activation gating of CaV1.2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12276–12284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808402200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordeiro JM, Marieb M, Pfeiffer R, Calloe K, Burashnikov E, Antzelevitch C. Accelerated inactivation of the L-type calcium current due to a mutation in CACNB2b underlies Brugada syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massa E, Kelly KM, Yule DI, MacDonald RL, Uhler MD. Comparison of fura-2 imaging and electrophysiological analysis of murine calcium channel alpha 1 subunits coexpressed with novel beta 2 subunit isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:707–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Link S, Meissner M, Held B, Beck A, Weissgerber P, Freichel M, Flockerzi V. Diversity and developmental expression of L-type calcium channel β2 proteins and their influence on calcium current in murine heart. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30129–30137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan BZ, Jiang F, Tan MY, Yu D, Huang H, Shen Y, Soong TW. Functional characterization of alternative splicing in the C terminus of L-type CaV1. 3 channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42725–42735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.265207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bock G, Gebhart M, Scharinger A, Jangsangthong W, Busquet P, Poggiani C, et al. Functional properties of a newly identified C-terminal splice variant of Cav1. 3 L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42736–42748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pérez-Alvarez A, Hernández-Vivanco A, Caba-González JC, Albillos A. Different roles attributed to Cav1 channel subtypes in spontaneous action potential firing and fine tuning of exocytosis in mouse chromaffin cells. J Neurochem. 2011;116:105–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji Y, Lalli MJ, Babu GJ, Xu Y, Kirkpatrick DL, Liu LH, et al. Disruption of a single copy of the SERCA2 gene results in altered Ca2+ homeostasis and cardiomyocyte function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38073–38080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fakira AK, Gaspers LD, Thomas AP, Li H, Jain MR, Elkabes S. Purkinje cell dysfunction and delayed death in plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2-heterozygous mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;51:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Empson RM, Akemann W, Knöpfel T. The role of the calcium transporter protein plasma membrane calcium ATPase PMCA2 in cerebellar Purkinje neuron function. Funct Neurol. 2010;25:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ficarella R, Di Leva F, Bortolozzi M, Ortolano S, Donaudy F, Petrillo M, et al. A functional study of plasma- membrane calcium-pump isoform 2 mutants causing digenic deafness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609775104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cestèle S, Scalmani P, Rusconi R, Terragni B, Franceschetti S, Mantegazza M. Self-limited hyperexcitability: Functional effect of a familial hemiplegic migraine mutation of the Nav1.1 (SCN1A) Na+ channel. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7273–7283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4453-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanmolkot KR, Babini E, deVries B, Stam AH, Freilinger T, Terwindt GM, et al. The novel p.L1649Q mutation in the SCN1A epilepsy gene is associated with familial hemiplegic migraine: Genetic and functional studies. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:522. doi: 10.1002/humu.9486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Estacion M, Han C, Choi JS, Hoeijmakers J, Lauria G, Drenth J, et al. Intra- and interfamily phenotypic diversity in pain syndromes associated with a gain-of-function variant of NaV1.7. Mol Pain. 2011;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Estacion M, Dib-Hajj S, Benke P, Te Morsche RH, Eastman E, Macala L, et al. NaV1.7 gain-of-function mutations as a continuum: A1632E displays physiological changes associated with erythromelalgia and paroxysmal extreme pain disorder mutations and produces symptoms of both disorders. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11079–11088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3443-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han C, Rush AM, Dib-Hajj SD, Li S, Xu Z, Wang Y, et al. Sporadic onset of erythermalgia: A gain-of-function mutation in Nav1.7. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:553–558. doi: 10.1002/ana.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dib-Hajj S, Rush A, Cummins T, Hisama F, Novella S, Tyrrell L, et al. Gain-of-function mutation in Nav1.7 in familial erythromelalgia induces bursting of sensory neurons. Brain. 2005;128:1847–1854. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shepard AR, Rae JL. Electrically silent potassium channel subunits from human lens epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C412–C424. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.3.C412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bocksteins E, Ottschytsch N, Timmermans JP, Labro A, Snyders D. Functional interactions between residues in the S1, S4, and S5 domains of Kv2.1. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:783–793. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wittekindt OH, Visan V, Tomita H, Imtiaz F, Gargus JJ, Lehmann-Horn F, et al. An apamin-and scyllatoxin- insensitive isoform of the human SK3 channel. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:788–801. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishii TM, Nakashima N, Ohmori H. Tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis in the S1 domain of mammalian HCN channel reveals residues critical for voltage-gated activation. J Physiol. 2007;579:291–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.